Maintaining Fertilization Supports Productivity in Second Rotation Eucalypt Plantations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Experimental Design

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

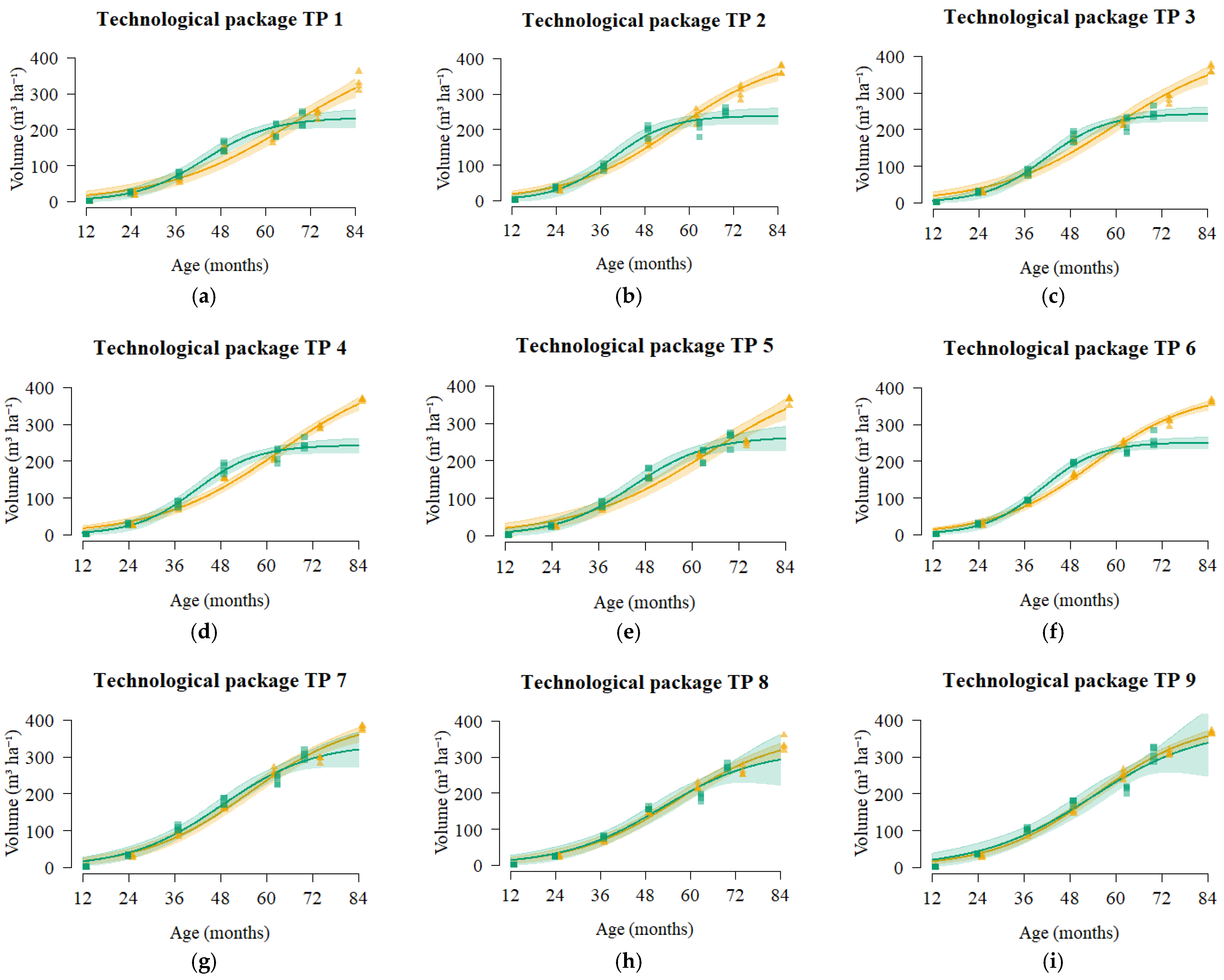

3.1. Model Fitting and Volume Estimation

3.2. Statistical and Graphical Comparison of Production Patterns

3.3. Contextual Analysis Based on Site Conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AG | Agrosilicon |

| ANP | Araxá Natural Phosphate |

| Bw | Latossolic B Horizon |

| Ca | Calcium |

| CBH | Circumference at Breast Height |

| DBH | Diameter at Breast Height |

| DTPA | Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic Acid |

| H | Total Height |

| K | Potassium |

| KCl | Potassium Chloride |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| MAI | Mean Annual Increment |

| Mg | Magnesium |

| N | Nitrogen |

| NPK | NPK Fertilizer |

| NRP | Natural Reactive Phosphate |

| P | Phosphorus |

| RMSE | Root Mean Square Error |

| RP | Residual Phosphate |

| Pearson correlation coefficient | |

| S | Sulfur |

| SA | Ammonium Sulfate |

| SSP | Single Superphosphate |

| TCA | Technical Cutting Age |

| TSP | Triple Superphosphate |

| V | Volume with Bark per hectare |

| Vi | Individual Volume with Bark |

References

- Indústria Brasileira de Árvores (IBÁ). Relatório Anual 2025: Ano Base 2024; IBÁ: São Paulo, Brazil, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, J.L.M.; Stape, J.L.; Laclau, J.P.; Gava, J.L. Silvicultural effects on the productivity and wood quality of eucalypt plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2004, 193, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crous, K.Y.; Ósvaldsson, A.; Ellsworth, D.S. Is phosphorus limiting in a mature Eucalyptus woodland? Phosphorus fertilization stimulates stem growth. Plant Soil 2015, 391, 293–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, M.; Amiotti, N.; Zalba, P. Response of phosphorus pools in Mollisols to afforestation with Pinus radiata D. Don in the Argentinean Pampa. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 422, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viana, T.O.; Gama-Rodrigues, A.C.; Gama-Rodrigues, E.F.; Aleixo, S.; Moreira, R.V.S.; Sales, M.V.S.; Marques, J.R.B. Phosphorus transformations in Alfisols and Ultisols under different land uses in the Atlantic Forest region of Brazil. Geoderma Reg. 2018, 14, e00184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novais, R.F.; Smyth, T.J.; Nunes, F.N. Phosphorus. In Fertilidade do Solo; Novais, R.F., Alvarez, V.H., Barros, N.F., Fontes, R.L.F., Cantarutti, R.B., Neves, J.C.L., Eds.; SBCS: Viçosa, Brazil, 2007; pp. 471–550. [Google Scholar]

- Melo, E.A.S.C.; Moraes, G.J.L.; Tertulino, J.H.; Hakamada, R.E.; Bazani, J.H.; Wenzel, A.V.A.; Arthur, J.C., Jr.; Borges, J.S.; Malheiros, R.; Lemos, C.C.Z.L.; et al. Responses of clonal eucalypt plantations to N, P and K fertilizer application in different edaphoclimatic conditions. Forests 2016, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albaugh, T.; Rubilar, R.A.; Maier, C.A.; Acuña, E.A.; Cook, R.L. Biomass and nutrient mass of Acacia dealbata and Eucalyptus globulus bioenergy plantations. Biomass Bioenergy 2017, 97, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrero, O.; Stape, J.L.; Allen, L.; Arrevillaga, M.C.; Ladeira, M. Productivity gains from weed control and fertilization of short-rotation Eucalyptus plantations in the Venezuelan Western Llanos. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 430, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, M.A.; Santos, D.R.; Tiecher, T.; Minella, J.P.G.; Barros, C.A.P.; Ramon, R. Phosphorus dynamics during storm events in a subtropical rural catchment in southern Brazil. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 261, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciano, C.; Goya, J.F.; Frangi, J.L.; Guiamet, J.J. Fertilization with phosphorus increases soil nitrogen absorption in young plants of Eucalyptus grandis. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2006, 36, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stape, J.L.; Binkley, D.; Ryan, M.G.; Fonseca, S.; Loos, R.A.; Takahashi, E.N.; Silva, C.R.; Silva, S.R.; Hakamada, E.; Ferreira, J.M.A.; et al. The Brazil Eucalyptus potential productivity project: Influence of water, nutrients and stand uniformity on wood production. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 1684–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.G.; Gama-Rodrigues, A.C.; Gonçalves, J.L.M.; Gama-Rodrigues, E.F.; Sales, M.V.S.; Aleixo, S. Labile and non-labile fractions of phosphorus and its transformations in soil under Eucalyptus plantations, Brazil. Forests 2016, 7, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassaco, M.V.M.; Motta, A.C.V.; Pauletti, V.; Prior, S.A.; Nisgoski, S.; Ferreira, C.F. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium requirements for Eucalyptus urograndis plantations in Southern Brazil. New For. 2018, 49, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendham, D.S.; O’Connell, A.M.; Grove, T.S.; Rance, S.J. Residue management effects on soil carbon and nutrient contents and growth of second rotation eucalypts. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 181, 357–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, J.D.; Jones, D.L.; Reynolds, B.; Price, M.H.; Healey, J.R. Whole tree harvesting can reduce second rotation forest productivity. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 257, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laclau, J.P.; Ranger, J.; Gonçalves, J.L.M.; Maquere, V.; Krusche, A.V.; M’Bou, A.T.; Nouvellon, Y.; Saint-André, L.; Bouillet, J.P.; Piccolo, M.; et al. Biogeochemical cycles of nutrients in tropical Eucalyptus plantations: Main features shown by intensive monitoring in Congo and Brazil. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 259, 1771–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, G.G.; Queiroz, T.B.; Kupper, A.P.; Masullo, L.; Hakamada, R.; Guerrini, I.A. Optimizing forest residue management after harvesting: Nutrient export scenarios in Eucalyptus plantations across high forest and coppice systems. Forestry 2025, cpaf044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, R.C.; Deus, J.C., Jr.; Nouvellon, Y.; Campoe, O.C.; Stape, J.L.; Aló, L.L.; Guerrini, I.A.; Jourdan, C.; Laclau, J. A fast exploration of very deep soil layers by Eucalyptus seedlings and clones in Brazil. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 366, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, A.S.; Gonçalves, J.L.M.; Gonçalves, A.N. Effect of nutrients omission in the Eucalyptus shoots. Nucleus 2017, 14, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.L.M.; Alvares, C.A.; Behling, M.; Alves, J.M.; Pizzi, G.T.; Angeli, A. Productivity of eucalypt plantations managed under high forest and coppice systems, depending on edaphoclimatic factors. Sci. For. 2014, 42, 411–419. [Google Scholar]

- Lafetá, B.O.; Santana, R.C.; Oliveira, M.L.R.; Leite, H.G.; Soares, L.C.S.; Vieira, D.S. Eucalypt production in different rotations, sites and spatial arrangements. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 571, 122222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantarutti, R.B.; Barros, N.F.; Prieto, H.E.; Novais, R.F. Avaliação da fertilidade do solo e recomendação de fertilizantes. In Fertilidade do Solo; Novais, R.F., Alvarez, V.H., Barros, N.F., Fontes, R.L.F., Cantarutti, R.B., Neves, J.C.L., Eds.; SBCS: Viçosa, Brazil, 2007; pp. 471–550. [Google Scholar]

- Barros, N.F.d.; Novais, R.F.; Teixeira, J.L.; Fernandes Filho, E.I. NUTRICALC 2.0—Sistema para cálculo del balance nutricional y recomendación de fertilizantes para el cultivo de eucalipto. Bosque 1995, 16, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.M.; Watts, D.G. Nonlinear Regression Analysis and Its Applications; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, I.; Gominho, J.; Pereira, H. Heartwood, sapwood and bark variation in coppiced Eucalyptus globulus trees in 2nd rotation and comparison with the single-stem 1st rotation. Silva Fenn. 2015, 49, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.G.; Santana, R.C.; Oliveira, M.L.R.; Gomes, F.S. Evaluation of different silvicultural management techniques and water seasonality on eucalyptus yield. Sci. Agric. 2022, 79, e20200064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinkhoff, R.E.; Mendham, D.; Hunt, M.A.; Britton, T.G.; Hovenden, M.J. The response of mid-rotation Eucalyptus nitens to nitrogen fertiliser is non-linear and not influenced by phosphorus application. For. Ecol. Manag. 2024, 561, 121897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiz, L.; Møller, I.M.; Murphy, A.; Zeiger, E. Plant Physiology and Development, 7th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, R.F.; Leite, S.R.; Santos, D.A.; Barrozo, M.A.S. Drum granulation of single super phosphate fertilizer: Effect of process variables and optimization. Powder Technol. 2017, 321, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Rotations | Soil Chemical Attributes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | OM (g dm−3) | P(resin) (mg dm−3) | K (mg dm−3) | Ca (cmolc dm3) | Mg (cmolc dm3) | |

| 1st | 4.1 | 39.5 | 3.7 | 15.6 | 0.22 | 0.08 |

| 2nd | 4.3 | 40.4 | 4.1 | 15.6 | 0.24 | 0.08 |

| S-SO4 (mg dm−3) | B (mg dm−3) | Cu (mg dm−3) | Fe (mg dm−3) | Mn (mg dm−3) | Zn (mg dm−3) | |

| 1st | 7.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 109.0 | 0.9 | 0.4 |

| 2nd | 7.6 | 0.6 | 0.2 | 117.0 | 1.2 | 0.6 |

| Packages | Basal Fertilization | Topdressing Fertilization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kg ha−1) | (g plant−1) | (Mg ha−1) | (kg ha−1) | (kg ha−1) | |

| TP1 | 500 ANP | 130 NPK | 2 AG | 210 KCl | 210 KCl |

| TP2 | 600 SSP | 130 NPK | 2 AG | 210 KCl | 210 KCl |

| TP3 | 280 TSP | 130 NPK | 2 AG | 210 KCl | 210 KCl |

| TP4 | 860 RP | 130 NPK | 2 AG | 210 KCl | 210 KCl |

| TP5 | 400 NRP | 130 NPK | 2 AG | 210 KCl | 210 KCl |

| TP6 | 500 ANP | 130 NPK | 2 AG | 210 KCl + 200 SA | 210 KCl + 400 SA |

| TP7 | 280 TSP | 130 NPK | 2 AG | 210 KCl + 200 SA | 210 KCl + 400 SA |

| TP8 | 500 ANP | 130 NPK | 1 AG | 210 KCl | 210 KCl |

| TP9 | 280 TSP | 130 NPK | 1 AG | 210 KCl + 200 SA | 210 KCl + 400 SA |

| Package | MAE | RMSE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ------------------------- 1st Rotation ------------------------- | ||||||

| TP1 | 434.3286 | 49.4904 | 0.0580 | 16.04 | 19.92 | 0.98 ** |

| TP2 | 408.9646 | 50.5419 | 0.0694 | 12.81 | 15.37 | 0.99 ** |

| TP3 | 418.6802 | 46.6026 | 0.0646 | 15.26 | 18.01 | 0.99 ** |

| TP4 | 448.7831 | 54.6627 | 0.0634 | 11.72 | 13.39 | 0.99 ** |

| TP5 | 443.5112 | 43.5550 | 0.0587 | 18.63 | 21.34 | 0.99 ** |

| TP6 | 384.7184 | 67.7944 | 0.0780 | 8.21 | 9.80 | 1.00 ** |

| TP7 | 404.2187 | 55.5387 | 0.0726 | 13.51 | 16.11 | 0.99 ** |

| TP8 | 360.2595 | 61.4684 | 0.0729 | 12.53 | 15.75 | 0.99 ** |

| TP9 | 395.1711 | 59.0284 | 0.0747 | 10.55 | 11.82 | 1.00 ** |

| ------------------------- 2nd Rotation ------------------------- | ||||||

| TP1 | 232.5159 | 126.5257 | 0.1109 | 10.67 | 13.65 | 0.99 ** |

| TP2 | 238.1158 | 158.9645 | 0.1293 | 12.63 | 16.31 | 0.98 ** |

| TP3 | 242.7047 | 187.5699 | 0.1261 | 9.15 | 12.78 | 0.99 ** |

| TP4 | 300.6563 | 57.5854 | 0.0838 | 13.77 | 17.53 | 0.98 ** |

| TP5 | 263.3778 | 103.7745 | 0.1038 | 12.00 | 15.85 | 0.99 ** |

| TP6 | 250.5299 | 228.5574 | 0.1342 | 7.37 | 10.85 | 0.99 ** |

| TP7 | 335.9723 | 55.0127 | 0.0831 | 13.89 | 16.59 | 0.99 ** |

| TP8 | 317.5659 | 56.5937 | 0.0772 | 15.89 | 19.05 | 0.98 ** |

| TP9 | 377.8788 | 40.6167 | 0.0693 | 19.08 | 22.71 | 0.98 ** |

| Packages | 1st Rotation | 2nd Rotation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCA (Months) | Volume (Months) | TCA (Months) | Volume (m3 ha−1) | |

| TP1 | 89.98 | 342.55 | 55.52 (61.70%) | 183.37 (53.53%) |

| TP2 | 75.50 | 322.54 | 49.39 (65.42%) | 187.82 (58.23%) |

| TP3 | 79.85 | 330.18 | 51.95 (65.06%) | 191.41 (57.97%) |

| TP4 | 83.88 | 353.93 | 64.08 (76.39%) | 237.10 (66.99%) |

| TP5 | 86.73 | 349.79 | 57.41 (66.19%) | 207.72 (59.38%) |

| TP6 | 70.94 | 303.41 | 50.29 (70.89%) | 197.59 (65.12%) |

| TP7 | 73.47 | 318.79 | 64.07 (87.21%) | 264.96 (83.11%) |

| TP8 | 74.56 | 284.12 | 69.34 (93.00%) | 250.47 (88.15%) |

| TP9 | 72.22 | 311.65 | 72.46 (100.33%) | 298.05 (95.63%) |

| Groups | p-Value | Groups | p-Value | Groups | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st Rotation | 2nd Rotation | Combined rotations | |||

| TP1 a TP9 | ≤0.01 | TP1 a TP9 | ≤0.01 | TP7 a TP9 | ≤0.01 |

| TP1-TP6-TP8 | ≤0.01 | TP1-TP6-TP8 | ≤0.01 | TP7-TP8 | ≤0.01 |

| TP3-TP7-TP9 | 0.71 | TP3-TP7-TP9 | ≤0.01 | TP7-TP9 | 0.40 |

| TP7 a TP9 | ≤0.01 | TP7 a TP9 | ≤0.01 | TP8-TP9 | ≤0.01 |

| TP1 a TP6 | ≤0.01 | TP1 a TP6 | 0.02 | - | - |

| TP1-TP4-TP5 | 0.03 | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Martins, N.S.; Lafetá, B.O.; Oliveira, M.L.R.; Santana, R.C. Maintaining Fertilization Supports Productivity in Second Rotation Eucalypt Plantations. Forests 2026, 17, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010013

Martins NS, Lafetá BO, Oliveira MLR, Santana RC. Maintaining Fertilization Supports Productivity in Second Rotation Eucalypt Plantations. Forests. 2026; 17(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartins, Nivaldo S., Bruno O. Lafetá, Marcio L. R. Oliveira, and Reynaldo C. Santana. 2026. "Maintaining Fertilization Supports Productivity in Second Rotation Eucalypt Plantations" Forests 17, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010013

APA StyleMartins, N. S., Lafetá, B. O., Oliveira, M. L. R., & Santana, R. C. (2026). Maintaining Fertilization Supports Productivity in Second Rotation Eucalypt Plantations. Forests, 17(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010013