Mycorrhizal Fungi, Heavy Metal Contamination, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Forest Soils

Abstract

1. Introduction

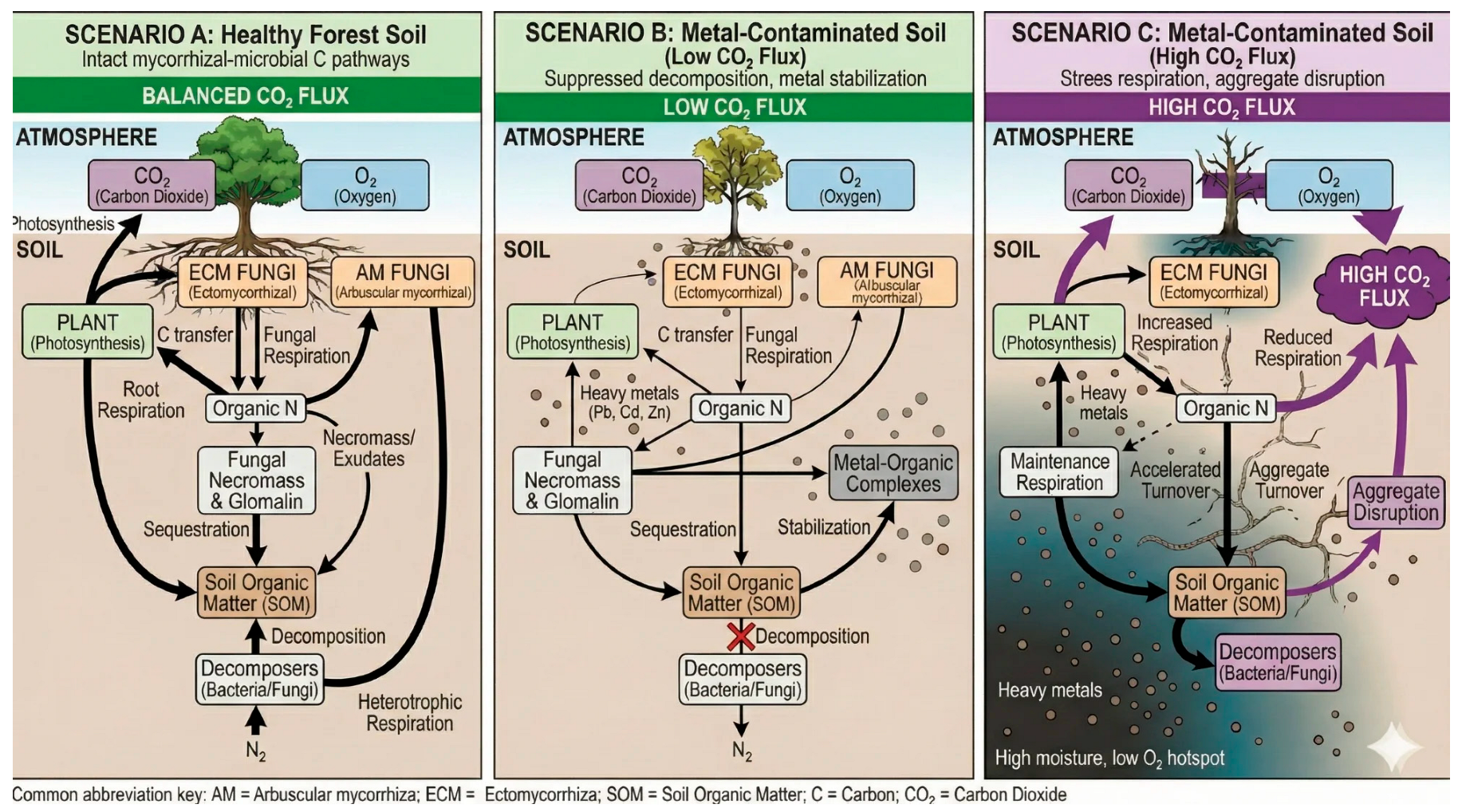

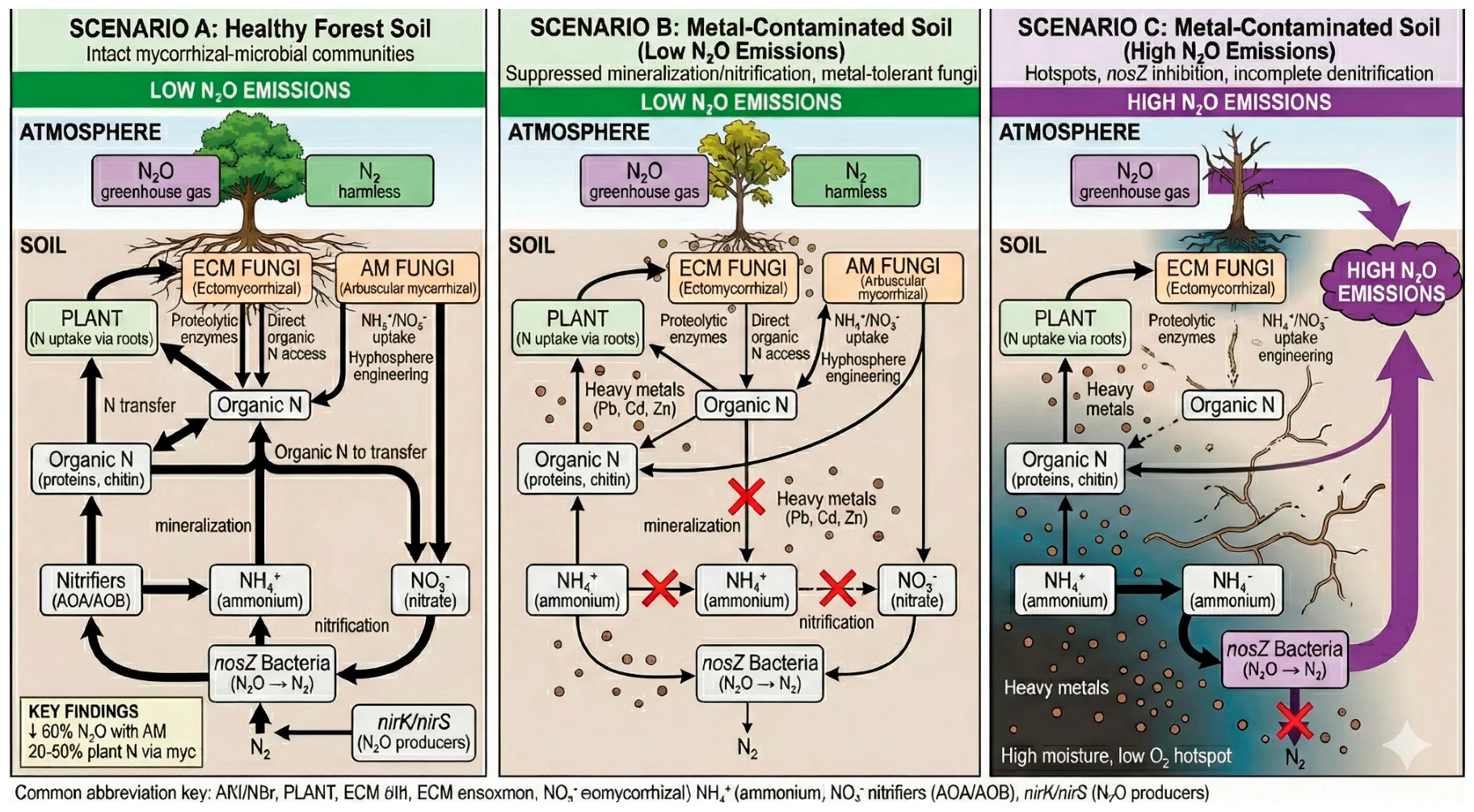

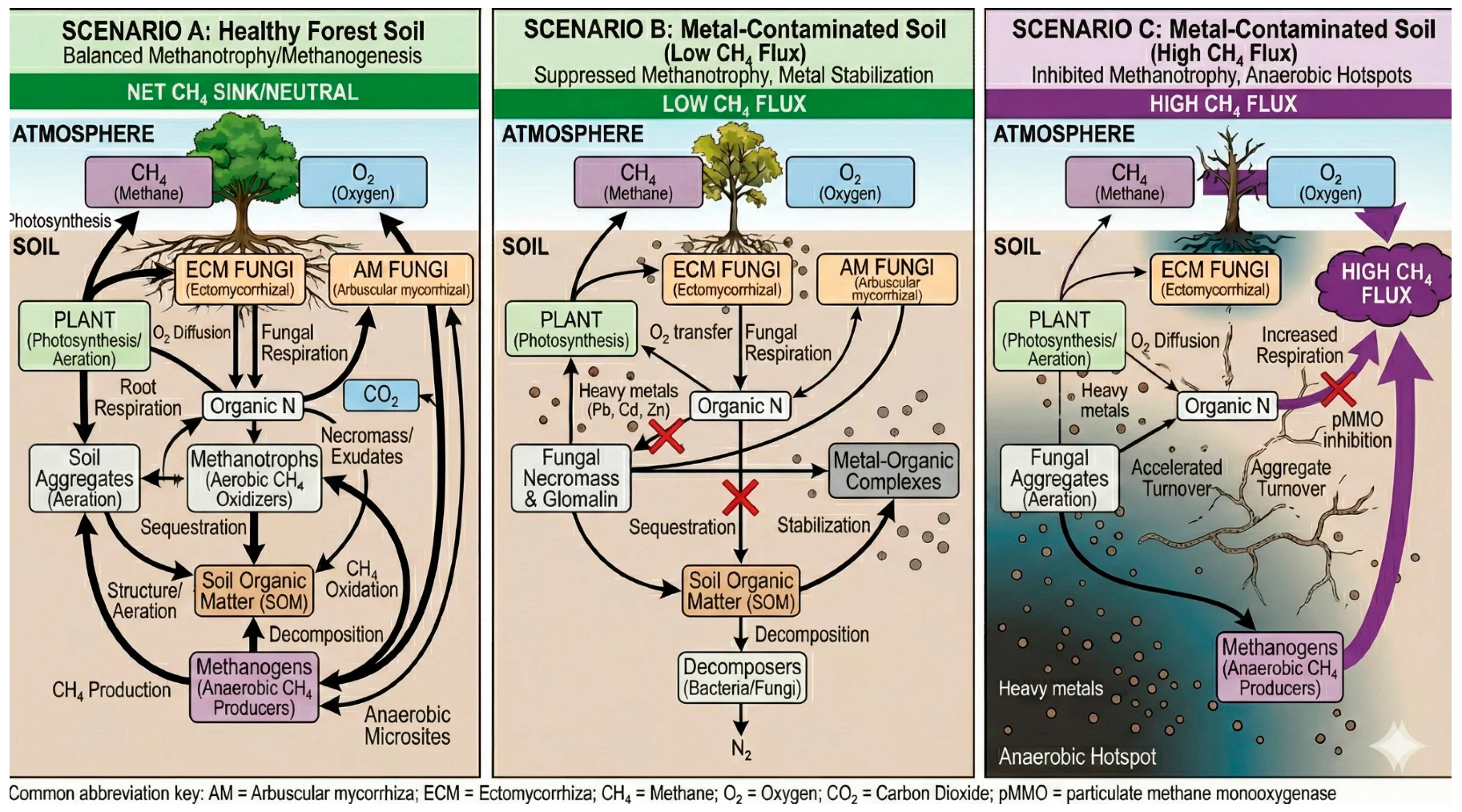

1.1. The Mycorrhiza–Metal–Greenhouse Gas Nexus

1.2. A Conceptual Framework: Three Contamination Scenarios

1.3. Four Mechanistic Pathways

1.4. Metal-Specific Considerations

1.5. Mycorrhizal Guild Identity and Ecosystem Context

2. Search Strategy and Conceptual Synthesis

3. Carbon Cycling and CO2 Dynamics

3.1. Mycorrhizal Carbon Transfer

3.2. Metal-Induced Alterations in Carbon Allocation

3.3. Respiratory Responses to Metal Stress

3.4. Decomposition Dynamics: The Gadgil Effect and Beyond

3.5. Long-Term Carbon Sequestration: Glomalin and Necromass

4. Nitrogen Cycling and N2O Emissions

4.1. Mycorrhizal Regulation of Nitrogen Availability

4.2. Metal Impacts on the Denitrification Pathway

4.3. Mycorrhiza–Denitrifier Interactions Under Metal Stress

4.4. Structural Controls on Denitrification Microsites

5. Methane Cycling and CH4 Dynamics

5.1. Mycorrhizal Influences on Methane Balance

5.2. Metal Effects on Methanotroph–Methanogen Balance

5.3. Copper: A Special Case for Methane Cycling

5.4. Evidence Gaps and Inferential Connections

6. Synthesis and Future Directions

6.1. Putting the Pieces Together

6.2. How Strong Is the Evidence?

6.3. Critical Research Gaps

6.4. What This Means for Management

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frey, S.D. Mycorrhizal fungi as mediators of soil organic matter dynamics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2019, 50, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, S.; Didwania, N.; Choudhary, R. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF): A pathway to sustainable soil health, carbon sequestration, and greenhouse gas mitigation. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2025, 24, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Han, X.; Liang, Y.; Ghosh, A.; Chen, J.; Tang, M. The combined effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and lead (Pb) stress on Pb accumulation, plant growth parameters, photosynthesis, and antioxidant enzymes in Robinia pseudoacacia L. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Meng, D.; Li, J.; Yin, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, X.; Cheng, C.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yan, M. Response of soil microbial communities and microbial interactions to long-term heavy metal contamination. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdu, N.; Abdullahi, A.A.; Abdulkadir, A. Heavy metals and soil microbes. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2017, 15, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyval, C.; Turnau, K.; Haselwandter, K. Effect of heavy metal pollution on mycorrhizal colonization and function: Physiological, ecological and applied aspects. Mycorrhiza 1997, 7, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, M.; Kamran, M.; Fang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Cao, H.; Yang, G.; Deng, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Anastopoulos, I.; et al. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi-induced mitigation of heavy metal phytotoxicity in metal contaminated soils: A critical review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 402, 123919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Der Heijden, M.G.A.; Martin, F.M.; Sanders, I.R. Mycorrhizal ecology and evolution: The past, the present, and the future. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1406–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, F.; Martin, F.M.; Van Der Heijden, M.G.A. The mycorrhizal symbiosis: Research frontiers in genomics, ecology, and agricultural application. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1486–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, E. Mycorrhizal symbiosis in plant growth and stress adaptation: From genes to ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2023, 74, 569–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diagne, N.; Ngom, M.; Djighaly, P.I.; Fall, D. Roles of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on plant growth and performance: Importance in biotic and abiotic stressed regulation. Diversity 2020, 12, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, A.E.; Classen, A.T. Climate change influences mycorrhizal fungal–plant interactions, but conclusions are limited by geographical study bias. Ecology 2020, 101, e02978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, N.; Zhang, W. Response of rhizosphere microenvironment to coupling of climate warming and soil pollution. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 375, 01010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel-Mikuš, K.; Pongrac, P.; Kump, P. Colonisation of a Zn, Cd and Pb hyperaccumulator Thlaspi praecox Wulfen with indigenous arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal mixture induces changes in heavy metal and nutrient uptake. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 139, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, S.; Ree, R.H. Serpentine soils do not limit mycorrhizal fungal diversity. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e11757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colpaert, J.V.; Wevers, J.H.L.; Krznaric, E.; Adriaensen, K. How metal-tolerant ecotypes of ectomycorrhizal fungi protect plants from heavy metal pollution. Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Becquer, T.; Rouiller, J.H.; Reversat, G.; Bernhard-Reversat, F.; Lavelle, P. Influence of heavy metals on C and N mineralisation and microbial biomass in Zn-, Pb-, Cu-, and Cd-contaminated soils. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2004, 25, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.; Rabow, S.; Rousk, J. Can heavy metal pollution stress reduce microbial carbon-use efficiencies? Soil Biol. Biochem. 2024, 195, 109458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M. Mycorrhizal types differ in ecophysiology and alter plant nutrition and soil processes. Biol. Rev. 2019, 94, 1857–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, S.F.; Plantenga, F.; Neftel, A.; Jocher, M.; Oberholzer, H.-R.; Köhl, L.; Giles, M.; Downward, T.; Van Der Heijden, M.G.A. Symbiotic relationships between soil fungi and plants reduce N2O emissions from soil. ISME J. 2014, 8, 1336–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlowska, T.E.; Charvat, I. Heavy-metal stress and developmental patterns of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 6643–6649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamoorthy, R.; Kim, C.; Subramanian, P.; Kim, K. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi community structure, abundance and species richness changes in soil by different levels of heavy metal and metalloid concentration. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, S.; Borie, F.; Bolan, N. Phytoremediation of metal-polluted soils by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 42, 741–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Chávez, M.C.; Carrillo-González, R.; Wright, S.F.; Nichols, K.A. The role of glomalin, a protein produced by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi, in sequestering potentially toxic elements. Environ. Pollut. 2004, 130, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; He, C.; Huang, L.; Ban, Y.; Tang, M. The effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on glomalin-related soil protein distribution, aggregate stability and their relationships with soil properties at different soil depths in lead-zinc contaminated area. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aponte, H.; Meli, P.; Butler, B.; Paolini, J.; Matus, F.; Merino, C.; Cornejo, P.; Kuzyakov, Y. Meta-analysis of heavy metal effects on soil enzyme activities. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Cui, Y.; Beiyuan, J.; Wang, X.; Duan, C.; Fang, L. Heavy metal pollution increases soil microbial carbon limitation: Evidence from ecological enzyme stoichiometry. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2021, 3, 230–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggioli, V.; Cabello, M.N.; Grilli, G.; Vasar, M.; Covacevich, F.; Öpik, M. Soil lead pollution modifies the structure of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal communities. Mycorrhiza 2019, 29, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, X.; Zhan, F.; Xie, C.; Fan, G. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi reduce cadmium leaching from polluted soils under simulated heavy rainfall. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 263, 114406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Xiaodong, Y.; Yunxiao, C.; Jiani, Y.; Shan, W.; Yunxia, L. The effects of diverse microbial community structures, driven by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inoculation, on carbon release from a paddy field. Plant Soil Environ. 2024, 70, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Booker, F.L.; Tu, C.; Burkey, K.O.; Zhou, L.; Shew, H.D.; Rufty, T.W.; Hu, S. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi increase organic carbon decomposition under elevated CO2. Science 2012, 337, 1084–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, H.; Cargill, R.I.M.; Van Nuland, M.E.; Hagen, S.C.; Field, K.J.; Sheldrake, M.; Soudzilovskaia, N.A.; Kiers, E.T. Mycorrhizal mycelium as a global carbon pool. Curr. Biol. 2023, 33, R560–R573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Wei, F.; Rillig, M.C.; Chen, B.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Huang, L. Soil organic matter dynamics mediated by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi—An updated conceptual framework. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1417–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, A.; Muhammad, M.; Munir, A.; Abdi, G.; Zaman, W.; Ayber, A.; Sharif, E.; Rahim, R. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in regulating growth, enhancing productivity, and potentially influencing ecosystems under abiotic and biotic stresses. Plants 2023, 12, 3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okiobe, S.T.; Augustin, J.; Veresoglou, S.D. Disentangling direct and indirect effects of mycorrhiza on nitrous oxide activity and denitrification. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 134, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Man, J.; Lehmann, A.; Rillig, M.C. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi attenuate negative impact of drought on soil functions. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Hu, J.; Zhang, T.; Wu, X.; Yang, Y. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and glomalin play a crucial role in soil aggregate stability in Pb-contaminated soil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Li, S.; Chen, S.; Ren, T.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, H. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi regulate soil respiration and its response to precipitation change in a semiarid steppe. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 19990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rillig, M.C.; Wright, S.F.; Eviner, V.T. The role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and glomalin in soil aggregation: Comparing effects of five plant species. Plant Soil 2002, 238, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.G. Role of soil microbes in the rhizospheres of plants growing on trace metal contaminated soils in phytoremediation. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2005, 18, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfante, P.; Anca, I.-A. Plants, mycorrhizal fungi, and bacteria: A network of interactions. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 63, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenoir, I.; Fontaine, J.; Sahraoui, A.L. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal responses to abiotic stresses: A review. Phytochemistry 2016, 123, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.; Hempel, S.; Wubet, T.; Schäfer, T.; Callaham, M.A.; All, J.G.; König, S.; Until, F.; Menge, D. Molecular diversity of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in relation to soil chemical properties and heavy metal contamination. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 2757–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, N.; Jumpponen, A.; Niskanen, T.; Liimatainen, K.; Jones, K.L.; Koivula, T.; Romantschuk, M.; Strömmer, R. EcM fungal community structure, but not diversity, altered in a Pb-contaminated shooting range in a boreal coniferous forest site in Southern Finland. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 76, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semrau, J.D.; DiSpirito, A.A.; Yoon, S. Methanotrophs and copper. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010, 34, 496–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semrau, J.D.; DiSpirito, A.A.; Gu, W.; Yoon, S. Metals and methanotrophy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02289-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorobev, A.; Jagadevan, S.; Baral, B.S.; DiSpirito, A.A.; Freemeier, B.C.; Bergman, B.H.; Bandow, N.L.; Semrau, J.D. Detoxification of mercury by methanobactin from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 5918–5926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argiroff, W.A.; Zak, D.R.; Pellitier, P.T.; Upchurch, R.A.; Belke, J.P. Decay by ectomycorrhizal fungi couples soil organic matter to nitrogen availability. Ecol. Lett. 2022, 25, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, B.D.; Tunlid, A. Ectomycorrhizal fungi—Potential organic matter decomposers, yet not saprotrophs. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1443–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bierza, W.; Bierza, K.; Trzebny, A.; Trocha, L.K. The communities of ectomycorrhizal fungal species associated with Betula pendula Roth and Pinus sylvestris L. growing in heavy-metal contaminated soils. Plant Soil 2020, 457, 321–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Martínez, M.; López-García, Á.; Domínguez, M.T.; Navarro-Fernández, C.M.; Kjøller, R.; Tibbett, M.; Marañón, T. Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities and their functional traits mediate plant–soil interactions in trace element contaminated soils. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bmmd, H.; Kwa, M.; Jpd, L.; Pn, Y. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi as a potential tool for bioremediation of heavy metals in contaminated soil. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2021, 10, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-Ramos, L.Y.; Coto-López, C.; Andrade-Torres, A. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in remediation of anthropogenic soil pollution. Symbiosis 2021, 84, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhlbachova, G.; Sagova-Mareckova, M.; Omelka, M.; Szakova, J.; Tlustos, P. The influence of soil organic carbon on interactions between microbial parameters and metal concentrations at a long-term contaminated site. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 502, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, M.; Wang, G.; Hu, Z.; Tian, M. Effects of lead pollution on soil microbial community diversity and biomass and on invertase activity. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2023, 5, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querejeta, J.I.; Schlaeppi, K.; López-García, Á.; Öpik, M.; Hedlund, K.; Strömberg, M.; Van Der Heijden, M.G.A. Lower relative abundance of ectomycorrhizal fungi under a warmer and drier climate is linked to enhanced soil organic matter decomposition. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 1399–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubov, M.; Schieber, B.; Janík, R. Seasonal dynamics of macronutrients in aboveground biomass of two herb-layer species in a beech forest. Biologia 2019, 74, 1181–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekblad, A.; Wallander, H.; Godbold, D.L. The production and turnover of extramatrical mycelium of ectomycorrhizal fungi in forest soils: Role in carbon cycling. Plant Soil 2013, 366, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, A.; Hallin, S.; Finlay, R.D. A tipping point in carbon storage when forest expands into tundra is related to mycorrhizal recycling of nitrogen. Ecol. Lett. 2021, 24, 1193–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, N.; Qin, C.; Ahanger, M.A.; Raza, S.; Khan, M.I.; Ashraf, M.; Ahmed, N.; Zhang, L. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant growth regulation: Implications in abiotic stress tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miransari, M. Hyperaccumulators, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and stress of heavy metals. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 645–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt, U.; Regvar, M.; Bothe, H. Arbuscular mycorrhiza and heavy metal tolerance. Phytochemistry 2007, 68, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissenhorn, I.; Leyval, C.; Berthelin, J. Cd-tolerant arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi from heavy-metal polluted soils. Plant Soil 1993, 157, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fransson, P. Elevated CO2 impacts ectomycorrhiza-mediated forest soil carbon flow: Fungal biomass production, respiration and exudation. Fungal Ecol. 2012, 5, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, K.M.; Khan, K.S.; Billah, M.; Akhtar, M.S.; Rukh, S.; Alam, S.; Munir, A.; Arshad, A.; Kamran, M.; Kaleri, A.R.; et al. Immobilization of Cd, Pb and Zn through organic amendments in wastewater irrigated soils. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.W.; Kennedy, P.G. Revisiting the ‘Gadgil effect’: Do interguild fungal interactions control carbon cycling in forest soils? New Phytol. 2016, 209, 1382–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill, C.; Hawkes, C.V. Ectomycorrhizal fungi slow soil carbon cycling. Ecol. Lett. 2016, 19, 937–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterkenburg, E.; Clemmensen, K.E.; Ekblad, A.; Finlay, R.D.; Lindahl, B.D. Contrasting effects of ectomycorrhizal fungi on early and late stage decomposition in a boreal forest. ISME J. 2018, 12, 2187–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.; Rewald, B.; Matthews, B.; Sanden, H.; Rosinger, C.; Kettner, K.; Tarvainen, L.; Lindroos, A.-J.; Lavé, J.K.; Leppälammi-Kujansuu, J.; et al. Soil fertility determines whether ectomycorrhizal fungi accelerate or decelerate decomposition in a temperate forest. New Phytol. 2023, 239, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chore, E.M.; Treseder, K.K. Mycorrhizal fungi modify decomposition: A meta-analysis. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 2763–2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, R.P.; Brzostek, E.; Midgley, M.G. The mycorrhizal-associated nutrient economy: A new framework for predicting carbon-nutrient couplings in temperate forests. New Phytol. 2013, 199, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niemeyer, J.C.; Lolata, G.B.; de Carvalho, G.M.; Da Silva, E.M.; Sousa, J.P.; Nogueira, M.A. Microbial indicators of soil health as tools for ecological risk assessment of a metal contaminated site in Brazil. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2012, 59, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, L.; Marjanovic, Z.; Prieto-Rubio, J.; Calderón-Sanou, I.; Karami, Y.; Luis, P.; Maurice, J.P.; Richard, F.; Selosse, M.A.; Martin, F.; et al. Metatranscriptomics sheds light on the links between the functional traits of fungal guilds and ecological processes in forest soil ecosystems. New Phytol. 2024, 242, 1676–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, F.; Nicolás, C.; Bentzer, J.; Ellström, M.; Smits, M.; Rineau, F.; Canbäck, B.; Floudas, D.; Carleer, R.; Lackner, G.; et al. Ectomycorrhizal fungi decompose soil organic matter using oxidative mechanisms adapted from saprotrophic ancestors. New Phytol. 2016, 209, 1705–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Núñez, J.A.; Albanesi, A.S. Ectomycorrhizal fungi as biofertilizers in forestry. In Biostimulants in Plant Science; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, J.; Shi, G.; An, L.; Öpik, M.; Feng, H. Diverse communities of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi inhabit sites with very high altitude in Tibet Plateau. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011, 78, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterbach-Bahl, K.; Baggs, E.M.; Dannenmann, M.; Kiese, R.; Zechmeister-Boltenstern, S. Nitrous oxide emissions from soils: How well do we understand the processes and their controls? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2013, 368, 20130122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bücking, H.; Kafle, A. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in the nitrogen uptake of plants: Current knowledge and research gaps. Agronomy 2015, 5, 587–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tian, X.; Ma, L.; Feng, B.; Liu, Q.; Yuan, L.; Fan, C.; Huang, H.; Huang, H. Resistance of microbial community and its functional sensitivity in the rhizosphere hotspots to drought. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 161, 108360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.W.; Chen, D.; He, J.Z. Microbial regulation of terrestrial nitrous oxide formation: Understanding the biological pathways for prediction of emission rates. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 39, 729–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Xu, X.; Ye, Y.; Yu, S.; Wang, W. Intermediate soil acidification induces highest nitrous oxide emissions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Song, Y.; Li, S.; Xiong, Z. Responses of N2O production pathways and related functional microbes to temperature across greenhouse vegetable field soils. Geoderma 2019, 355, 113904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, T.; Wang, B.; Li, C.; Zeng, G. A review on airborne microorganisms in particulate matters: Composition, characteristics and influence factors. Environ. Int. 2018, 113, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gui, H.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, L.; Yan, K.; Xu, J. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi potentially regulate N2O emissions from agricultural soils via altered expression of denitrification genes. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 774, 145133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borton, M.; Oliverio, A.; Narrowe, A. Mapping the soil microbiome functions shaping wetland methane emissions. bioRxiv 2024. bioRxiv: 2024-02. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.P.; Schilling, J.S. Harnessing fungi to mitigate CH4 in natural and engineered systems. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 7365–7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitag, T.E.; Toet, S.; Ineson, P.; Prosser, J.I. Links between methane flux and transcriptional activities of methanogens and methane oxidizers in a blanket peat bog. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2010, 73, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capone, D.G.; Reese, D.D.; Kiene, R.P. Effects of organic pollutants on methanogenesis, sulfate reduction and carbon dioxide evolution in salt marsh sediments. Mar. Environ. Res. 1984, 13, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmett, B.D.; Lévesque-Tremblay, V.; Harrison, M.J. Conserved and reproducible bacterial communities associate with extraradical hyphae of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. ISME J. 2021, 15, 2276–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talbot, J.M.; Allison, S.D.; Treseder, K.K. Decomposers in disguise: Mycorrhizal fungi as regulators of soil C dynamics in ecosystems under global change. Funct. Ecol. 2008, 22, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasmín, S.; González-Chávez, M.C.A.; Carrillo-González, R.; Rodríguez-Dorantes, A.; Ruiz-Olivares, A. Responses of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant communities to long-term mining and passive restoration. Plants 2025, 14, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Scenario A | Scenario B | Scenario C |

|---|---|---|---|

| C transfer to fungi | 10–30% of NPP | Reduced | Severely diminished |

| Fungal respiration | Major CO2 source | Reduced | Fungal: reduced; Plant stress: elevated |

| Decomposition | Balanced | Suppressed | Old C exposed |

| Glomalin/necromass | 5–15% of SOC | Metal-stabilized | Production impaired |

| Net CO2 flux | Balanced | Low | Elevated |

| Parameter | Scenario A | Scenario B | Scenario C |

|---|---|---|---|

| N acquisition | ECM: organic; AM: inorganic | Reduced efficiency | Severely impaired |

| Mineral N pool | Low | Moderate | Elevated |

| NosZ community | Enriched | Reduced | Depleted |

| NosZ activity | Active | Inhibited | Severely inhibited |

| N2O:N2 ratio | Low | Elevated | High |

| Net N2O emission | Low | Variable | Elevated; hotspots |

| Parameter | Scenario A | Scenario B | Scenario C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil structure | Well-aggregated | Degraded | Collapsed |

| Anaerobic microsites | Limited | Expanding | Extensive |

| Methanotroph activity | Active | Suppressed | Inhibited |

| Methanogen habitat | Restricted | Expanding | Expanded |

| Net CH4 flux | Sink | Potential weakened sink | Source possible |

| Evidence quality | Moderate | Limited | Inferential |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Krchnavý, R.; Hudoková, H.; Kubov, M.; Jamnická, G.; Grenčíková, S.; Pavlík, M.; Kiiza, A.; Razzak, A.; Fleischer, P., Sr.; Fleischer, P., Jr. Mycorrhizal Fungi, Heavy Metal Contamination, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Forest Soils. Forests 2026, 17, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010012

Krchnavý R, Hudoková H, Kubov M, Jamnická G, Grenčíková S, Pavlík M, Kiiza A, Razzak A, Fleischer P Sr., Fleischer P Jr. Mycorrhizal Fungi, Heavy Metal Contamination, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Forest Soils. Forests. 2026; 17(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleKrchnavý, Radoslav, Hana Hudoková, Martin Kubov, Gabriela Jamnická, Sona Grenčíková, Martin Pavlík, Allen Kiiza, Abdul Razzak, Peter Fleischer, Sr., and Peter Fleischer, Jr. 2026. "Mycorrhizal Fungi, Heavy Metal Contamination, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Forest Soils" Forests 17, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010012

APA StyleKrchnavý, R., Hudoková, H., Kubov, M., Jamnická, G., Grenčíková, S., Pavlík, M., Kiiza, A., Razzak, A., Fleischer, P., Sr., & Fleischer, P., Jr. (2026). Mycorrhizal Fungi, Heavy Metal Contamination, and Greenhouse Gas Fluxes in Forest Soils. Forests, 17(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/f17010012