Abstract

Tree ferns are ubiquitous in New Zealand forests, but there is limited knowledge of their role in urban plant communities and potential use in restoration. We assessed sixteen sites by measuring 200 m2 plots to investigate how tree ferns influence vascular plant composition in Hamilton, North Island, New Zealand. The sixteen plots were assigned to four site type combinations based on restoration status (restored or unrestored) and tree fern presence, each with four plots. Average native plant species richness was higher at sites with tree ferns (36 ± 16; S = 68) than at sites without (19 ± 14; S = 41), with more diverse ground fern and epiphyte assemblages. Higher native plant richness at restored sites (34 ± 18; S = 62) compared to unrestored sites (20 ± 14, S = 44) was partially attributed to increased plant abundances. Multivariate analyses revealed differences in plant community composition among our site types. Angiosperms and conifers were less prevalent in plots with tree ferns, suggesting competitive relationships among these groups. However, tree ferns were associated with some shade-tolerant trees, such as Schefflera digitata J.R.Forst. & G.Forst. Indicator species of sites with tree ferns were mainly ground ferns and epiphytes (e.g., Blechnum parrisiae Christenh. and Trichomanes venosum R.Br.), whereas species with high fidelity to sites without tree ferns were pioneer trees and shrubs (e.g., Pittosporum eugenioides A.Cunn.). Community structure analyses revealed that total basal areas were highest at unrestored sites with tree ferns, but restored sites exhibited more diverse tree communities. Environmental predictors that correlated significantly with the compositional differences among our site types were tree fern basal area and restoration age. Our results highlight the need to reconsider the potential of tree ferns in current restoration practice. Tree ferns were found to augment native plant diversity in our study, indicating their potential to enhance urban ecological restoration projects in New Zealand.

1. Introduction

Forests support a significant portion of global biodiversity and provide myriad ecosystem services. However, global forest loss is still high, mainly driven by agricultural and urban development [1,2]. Urban expansion places significant pressure on biodiversity via habitat loss and modification [3], but urban ecological restoration presents a unique nature-based solution to combat biodiversity loss and climate change [4,5]. As the number of urban restoration projects rises internationally [6], there is a growing need to contribute to current knowledge of urban plant community composition and assembly. Pioneer species play a critical role in ecological succession and community assembly, influencing the successional pathway and “climax” community [7,8]. Early-arriving plants also impact the functional diversity of ecosystems [9] and the number of colonising species via community competition [10]. Understanding how pioneers influence community composition is vital for successful restoration, allowing restoration practitioners to mimic natural succession and assist the recovery of disturbed ecosystems to support a fuller assemblage of species.

In New Zealand, restoration practitioners concentrate on restoring pioneer trees and shrubs [11], which we refer to as light-demanding angiosperm and conifer species first planted at restoration projects. In contrast, we are unaware of any urban restoration projects where tree ferns have been planted, despite also being important pioneers of conifer-broadleaved forests [12]. Tree ferns can act as ecological filters, either inhibiting or facilitating the regeneration of other plants [13,14,15]. When forming extensive thickets, tree ferns may arrest succession, restricting the arrival of pioneer angiosperms and conifers via shading effects and slow-decomposing fronds. For example, tree ferns suppressed podocarp regeneration in exotic [16] and indigenous forests [17,18,19,20]. A stand of Cyathea dealbata (G.Forst.) Sw. also restricted angiosperm establishment in secondary forests on the Coromandel Peninsula [21].

Previous research indicates that tree ferns can also accelerate successional processes [22]. For example, they contribute to soil development, provide slope stabilisation and are excellent phorophytes [23,24,25]. Tree ferns enhance habitat heterogeneity, influencing nutrient, light and water cycles via their megaphylls and providing substrate conducive to epiphyte establishment [26]. Furthermore, tree ferns can provide an important regeneration niche for angiosperms, mediating competition with conifers [27]. A study in the Waitutu Ecological District found that 60% of mature Pterophylla racemosa (L.f.) Pillon & H.C.Hopkins (a native angiosperm tree) regenerated epiphytically on tree ferns [13]. Tree fern stands may also provide a more suitable habitat for shade-tolerant species than pioneer trees. For example, forest dominated by Cyathea medullaris G.Forst.) Sw. supported more shade-tolerant species than Kunzea ericoides s.l. (A.Rich.) forest [28]. Furthermore, extant tree ferns may advance restoration by decades by providing a native canopy (a primary goal in ecological restoration) from the outset of projects. Common pioneer species planted in restoration projects, such as Leptospermum scoparium J.R.Forst. & G.Forst. and Kunzea ericoides, may take twenty years to reach a height of 7 m [29].

Research on community assembly and successional pathways following tree ferns is scarce. However, gullies and topographic depressions with early-colonising tree ferns (e.g., Dicksonia squarrosa (G.Forst.) Sw. and Cyathea medullaris) may encourage broadleaved scrub 35–50 years after disturbance, Beilschmiedia tawa (A.Cunn.) Benth. & Hook.f. ex Kirk forest after 150–350 years and Metrosideros robusta A.Cunn.–Dacrydium cupressinum Sol. ex G.Forst.–B. tawa forest after 400 years [30]. In Hamilton urban environments, successional pathways have diverged from natural forest trajectories due to the range of anthropogenic disturbances that influence plant communities. Images show that grey willow-dominated forest containing Dicksonia squarrosa established in some gullies more than 20 years after livestock grazing ceased when land was subdivided for housing development [31]. Although tree ferns form important pioneer communities of conifer-broadleaved forests in New Zealand, there is limited information on how these species influence urban plant communities.

We present the results from one of the first studies on urban tree fern communities in New Zealand; most research on tree ferns has focused on non-urban forests after natural, rather than anthropogenic disturbance. The aim of this study was to investigate how tree ferns influence urban plant communities and identify environmental variables contributing to community composition. We tested three hypotheses: (1) tree fern presence significantly affects vascular plant community composition at sites not actively restored by augmenting ground fern and epiphyte richness, (2) actively restored sites support richer, more abundant pioneer tree and shrub assemblages and (3) tree fern basal area and restoration age are important environmental predictors of compositional differences among our site types. Better understanding how tree ferns impact diversity and composition in urban plant communities will help guide ecological restoration activities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Indigenous vegetation cover is low in New Zealand’s major urban centres, ranging from <1 to 8.9% [32]. Urban forests support novel plant communities with a high prevalence of exotic species [33]. Research on restoring urban forests has focused on forest remnants or reconstructing native ecosystems using landforms to guide plantings [34,35]. With a focus on planting pioneer trees, there has been little research on existing pioneer tree ferns. Practitioners have also overlooked tree ferns and the native species they support; the blanket clearance of exotic trees, a common approach, is unfavourable to existing native plants, including tree ferns [36].

Hamilton is a small city (approximately 11,000 ha) located in the central North Island, New Zealand (37°46′59.99′′ S, 175°16′59.99′′ E). New Zealand has been identified as one of 25 world biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities [37]. Hamilton lies within the Hamilton Ecological District [38]. Hamilton has a temperate oceanic climate with a mean annual temperature of 13.7 °C and a mean annual precipitation of 1190 mm [39]. There is approximately 267 ha (2.5%) of native-dominant vegetation in Hamilton (HCC unpublished database). Hamilton’s natural vegetation is concentrated in gullies that form intricate networks throughout the city. The gullies formed 15,000 years ago via spring sapping when the Waikato River changed course, undermining banks, trapping sediment and creating a network of streams. Before human arrival, gully floors were dominated by semi-swamp species like Dacrycarpus dacrydioides (A.Rich.) de Laub. (kahikatea), Laurelia novae-zelandiae A.Cunn. (pukatea) and Syzygium maire (A.Cunn.) Sykes & Garn.-Jones (waiwaka) [34]. As rural land in Hamilton was converted to urban subdivisions, grey willow (Salix cinerea) rapidly became the dominant tree in the gullies. Compared to small, drained kahikatea remnants in Hamilton, the gullies, with their developed canopy, higher humidity and abundant tree ferns, may support more diverse native understory communities [40]. Hamilton’s gullies can also support rich assemblages of locally uncommon life forms, including epiphytes [41].

2.2. Site Selection

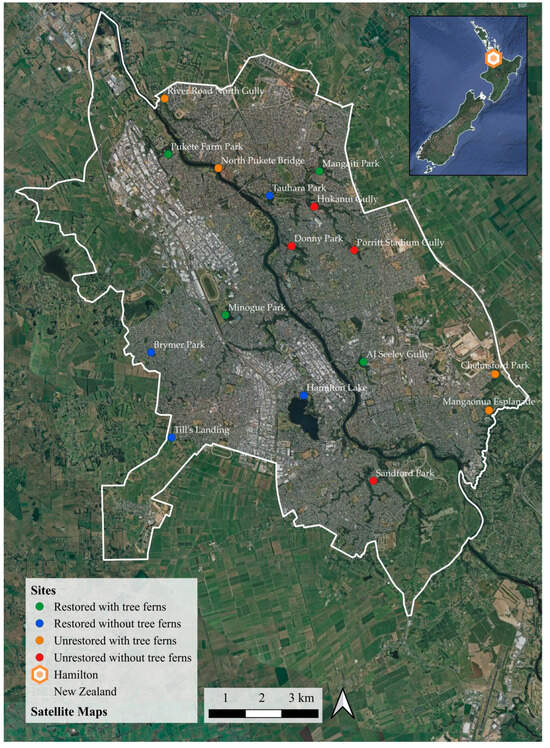

After an extensive survey of gullies and reserves in Hamilton, sixteen sites were selected (Figure 1). We adopted a fully crossed factorial design to investigate how tree fern presence influences urban plant communities while considering the impact of active plantings on these communities using restoration status. Our site types consisted of four categories: restored sites with tree ferns (n = 4), unrestored sites with tree ferns (n = 4), restored sites without tree ferns (n = 4) and unrestored sites without tree ferns (n = 4). Restored sites had been planted with native trees and shrubs (native tree basal area > 7 m2 ha−1), and unrestored sites had not been planted (<3 m2 ha−1). Sites with tree ferns had at least 12 individuals in a plot, and those without had three or fewer (see Figure 2 for site type examples). The thresholds used to determine site type were adopted as feasible targets for the study sites, enabling a comparison between sites with and without tree ferns.

Figure 1.

Site locations in Hamilton, North Island, New Zealand. Each dot represents a site where one 20 × 10 m2 vegetation plot was assessed, and the colour denotes the site type (i.e., green dots are restored sites with tree ferns, blue dots are restored sites without tree ferns, orange dots are unrestored sites with tree ferns and red dots are unrestored sites without tree ferns). A map of New Zealand is also provided, indicating the study location (Hamilton), near the centre of the North Island.

Figure 2.

Example sites of the four site types based on restoration status (restored, unrestored) and the presence of tree ferns (with, without).

Restoration age (i.e., the time since native plantings began) guided site selection and was sourced from an unpublished Hamilton City Council restoration database and verified using tree cores [42] (see Table S1, Supplementary Materials). The tree fern basal areas at sites with tree ferns (dominated by Dicksonia squarrosa) were similar to those recorded in younger (<80 years) podocarp–broadleaf forests on central North Island [19]. The soil types at our sites ranged from Kirikiriroa gritty silt loam, Te Kowhai silt loam, Tamahana silt loam, Kainui silt loam and Waikato loamy sand to Hamilton clay loam and Kaipaki peaty loam (Manaaki Whenua unpublished database). All four site types exhibited the two major soil types (Kirikiriroa gritty silt loam and Tamahana silt loam).

2.3. Vegetation Survey

A single vegetation plot (20 × 10 m2) was measured at each site, following a method developed by the People, Cities and Nature (PCaN) research programme and used in establishing a permanent plot network of 97 plots in nine cities across New Zealand [43]. Four permanent vegetation plots (200 m2) were selected from the PCaN plot network in Hamilton (n = 9) that met the restored sites without tree ferns’ site type requirements. The remaining twelve sites that met the requirements of the other three site types (i.e., not in the PCaN plot network) were selected separately; specific plot locations were identified using a random number generator. Our plots were half the area of the nationally developed forest methodology [44] because of the limited patch size and extent of vegetation in the urban context (Figure S1, Supplementary Materials).

Each plot was split into eight 5 m2 subplots, and measurements were obtained for ground cover, ground ferns, woody plants (trees and shrubs), tree ferns and epiphytes. The ground cover (%) per subplot was estimated visually using standard categories (i.e., herbaceous cover, leaf litter and sticks, moss and bare ground). Ground ferns were counted per subplot. For woody species, data were collected separately for seedlings (<1.35 m tall), saplings (>1.35 m tall but <2.5 cm diameter at breast height, DBH) and trees (woody species > 2.5 cm DBH). Tree ferns were counted per subplot; we only recorded tree fern diameters for individuals with a DBH greater than 2.5 cm. Vascular epiphyte measurements included abundance (count) and host species. The nomenclature follows the Flora of New Zealand [45].

In addition, variables that could influence the study communities were recorded, specifically canopy cover (using the %Cover CanopySurveying application), slope (using a SUUNTO PM-5 clinometer, Vantaa, Finland), canopy height (with a Haglöf Vertex IV Hypsometer, Långsele, Sweden) and geographical coordinates. A tree core from the largest individual was collected from each plot to estimate the maximum age and verify previously documented restoration ages (Table S1, Supplementary Materials). Distance from the patch edge (i.e., between the plot and vegetation margin) was determined using the Near geoprocessing tool in ArcGIS Pro (a geographic information system).

2.4. Data Analysis

We compared compositional differences among our four site types (i.e., unrestored sites with tree ferns, unrestored sites without tree ferns, restored sites with tree ferns and restored sites without tree ferns) and investigated environmental variables influencing these differences using a range of statistical approaches. Data was analysed and visualised in R version 4.2.2 [46]. Unless specified, all multivariate analyses used the “vegan” R package (version 2.7-1) [47].

2.4.1. Community Analysis

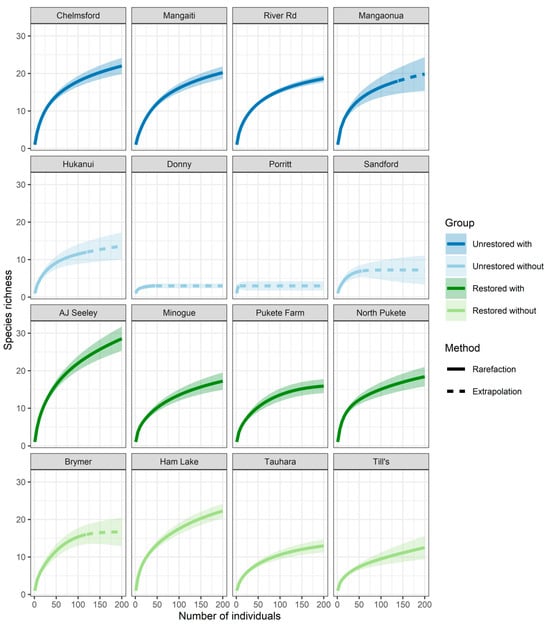

We investigated the influence of our site types on plant richness to test our first two hypotheses (i.e., tree ferns augment native plant richness, and restored sites hold more speciose and diverse plant communities). To account for differences in plant abundances, we estimated rarefied species richness for each plot and plant group (i.e., seedlings, saplings, trees, ground ferns and epiphytes) using a sample-size-based rarefaction and extrapolation (R/E) sampling curve approach with the “iNEXT” (version 3.0.0) R package [48]. Rarefaction curves were extrapolated to a higher number of individual plants for total native species richness (n = 200) than for exotic richness and individual plant groups (n = 50). The different approaches were explained by the lower abundances of the latter groups, requiring a smaller number of individuals to standardise richness (Figure A1).

We then fitted generalised linear models (GLMs) with restoration age as a covariate to test the influence of tree fern presence and restoration status on species abundances and richness of different plant groups (i.e., native and exotic plant species and individual plant groups, including seedlings, saplings, trees, ground ferns and epiphytes). We com-pared GLM results using raw (i.e., unrarefied) and rarefied species richness, but we pre-sent results for the latter, as rarefaction accounts for the influence of plant abundances on richness responses [48]. The GLMs using count data responses were fitted with a log link function, assuming a Poisson distribution. We tested the multivariate models for multicol-linearity using the variance inflation factor (VIF); all models achieved acceptable VIF val-ues below 5. We compared models with and without the interaction term using a likeli-hood ratio test to determine whether there were interactive effects between restoration sta-tus and tree fern presence. Where there was no statistically significant influence of the in-teraction, we present the additive model results. Post hoc comparisons were tested using a least-squares means approach with Tukey’s correction for multiplicity via the “lsmeans” package in R [49]. In addition to key model statistics provided in the written results, we present summary tables in the results with the 95% confidence interval for the parameter estimates of the GLMs and post hoc tests.

To assess how tree fern presence and restoration status influence plant community composition, we used a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) with abundance data for native and exotic species, combined and native species alone. The PERMANOVA tests were performed using the “adonis2” function in the “vegan” R package [47]. Community composition data were first Hellinger-transformed to simultaneously minimise the effects of vastly different total abundances and account for rare species [50]. The transformed community data using the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity was then analysed with PERMANOVA to test whether plant community composition differed among our four site types [51]. Each PERMANOVA model included restoration age as a covariate. To determine which plant species were influential in the PERMANOVA results, we used the “indicspecies” (version 1.8.0) R package to identify indicator species with high fidelity to our site types [52]. A nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination using the “metaMDS” function was used to visualise plant communities in each site type and help interpret the PERMANOVA results. Convex hulls were drawn around the four site types, and indicator species and the ten most abundant species (i.e., species ranked by dominance) were plotted using their axes scores.

We used basal areas (as an indicator of biomass) to test our first two hypotheses further regarding the influence of tree fern presence and restoration status on vascular plant communities. We fitted four GLMs (each assuming a Gaussian distribution) to investigate differences in total, native tree, exotic tree and tree fern basal areas among the site types with restoration age as a covariate. Model predictors in the GLMs had acceptable variance inflation factor (VIF) values < 5. Post hoc differences were tested using a least-squares means approach with Tukey’s correction for multiplicity. We also tested compositional differences in species basal areas among the site types using PERMANOVA, but we did not present the results, as they reiterate the same compositional differences among our site types found using species abundances.

2.4.2. Environmental Variable Analysis

To test our third hypothesis, we investigated the influence of potential environmental predictors on plant community responses, including species richness and community composition. Six GLMs were fitted to identify potential environmental predictors of richness for total native species and each plant group (i.e., seedlings, saplings, trees, ground ferns and epiphytes) using a log link function and assuming a Poisson distribution for count data. The ten environmental predictors we considered were average slope, canopy cover, restoration age, maximum tree age, maximum tree height, distance to the patch edge, and the total plant basal area, as well as the basal area of tree ferns, native trees and exotic trees. We assessed the normality of environmental predictors using Shapiro tests and log-transformed predictors to reduce skewness. Environmental predictors were then standardised (i.e., centred on the mean and scaled to unit variance) using the “decostand” function in the “vegan” R package. Rarefied richness integers were used for all models to account for differences in plant abundances across site types. The “step” R function was used to forward select important environmental predictors (from our ten predictors) of our univariate responses for each model.

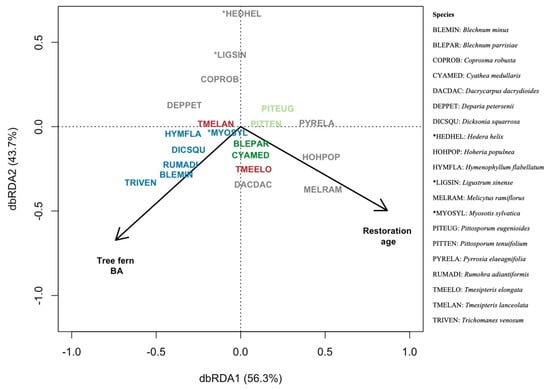

To consider potential environmental and spatial predictors of overall plant community composition and account for potential spatial autocorrelation, a distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) using the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity [53] was conducted on the Hellinger-transformed community data. The same ten log-transformed and standardised environmental predictors used for the univariate GLMs were considered for the dbRDA.

In our initial model fitting for the dbRDA, we also considered spatial structuring of plant communities (e.g., distance–decay relationships). The spatial structuring of plant community data using geographic coordinates for sites was assessed using a principal coordinates of neighbour matrices (PCNM) approach [54]. PCNM descriptors (or axes) may help describe processes structuring communities at different spatial scales [55]. PCNM axes were generated from site coordinates using the “pcnm” R function in the “vegan” package. The PCNM axes were used in the initial model selection procedure for the dbRDA, but none were selected, and they were not considered further.

To avoid overfitting the dbRDA model and select only influential predictors explaining variation in plant community composition, we used a forward stepwise procedure using the “ordistep” function [56]. Two predictors were selected for the final dbRDA model: tree fern basal area and restoration age. Variation partitioning was then undertaken to assess the relative contribution of tree fern basal area and restoration age to variation in community composition (Figure S2, Supplementary Materials). The significance of each independent variation component was permutation-tested using 1000 randomisations [57]. We used the “capscale” (dbRDA) and “varpart” (variation partitioning) functions for these constrained multivariate analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Plant Abundances and Richness

More than 6000 individuals of 155 native vascular plant species were recorded across 16 sites (Table 1). The generalised linear model (GLM) results showed significant differences in plant abundances and species richness with tree fern presence and restoration status (Table 2). Native plant abundances were significantly affected by the interaction between tree fern presence and restoration status (F1,11 = 12.0, p < 0.01). Post hoc results revealed that native plant abundances were higher at restored sites without tree ferns when compared to their unrestored equivalents (z = 2.7, p < 0.01), but unrestored sites with tree ferns exhibited higher native abundances than the restored sites (z = −9.7, p < 0.001). Restored sites without tree ferns presented higher native abundances than those with tree ferns (z = 6.3, p < 0.001), whereas the opposite was observed at unrestored sites with tree ferns, which showed higher abundances than unrestored sites without tree ferns (z = −35.6, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Mean (±standard deviation) native, exotic and total plant abundances, richness and rarefied richness at the four site types based on restoration status (restored, unrestored) and tree fern presence (with, without). The mean total (i.e., tree fern, native and exotic tree) basal areas (m2/ha) per site type are also presented.

Table 2.

Generalised linear model results testing the effect of tree fern presence and restoration status on total native abundances and rarefied species richness, as well as the abundance and rarefied richness of seedlings, ground ferns and epiphytes. Incidence rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are provided. Statistically significant p-values at α = 0.05 are in boldface. See Supplementary Materials, Table S2, for GLM results concerning total exotic plants, native saplings and trees abundances and richness.

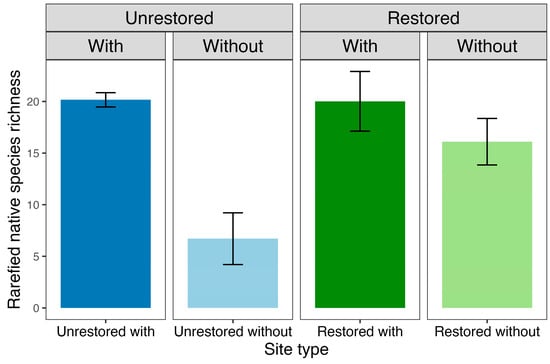

Native plant abundances appeared to partially affect native species richness, which was higher at restored sites, whether tree ferns were present (z = −5.1, p < 0.001) or absent (z = −3.2, p < 0.01). However, after accounting for differences in native plant abundances through rarefaction, the GLM revealed that the interaction between tree fern presence and restoration status had a significant effect on plant richness (F1,11 = 8.4, p < 0.05; see Figure 3). Tree fern presence positively influenced rarefied native plant richness at unrestored sites (z = −4.0, p < 0.001), but this influence was not statistically significant at restored sites (z = −1.0, p = 0.3). In contrast, restoration status positively affected native species richness at sites without tree ferns (z = 2.9, p < 0.01), but it did not have a significant influence at sites without tree ferns (z = −0.04, p = 1.0).

Figure 3.

Mean rarefied native vascular plant species richness for the four site types based on restoration status (restored, unrestored) and the presence of tree ferns (with, without). Error bars represent one standard error.

Exotic plant abundances were significantly lower at sites with tree ferns (F1,12 = 6.6, p < 0.05) but did not vary with restoration status (F1,12 = 2.4, p = 0.2). Furthermore, rarefied exotic species richness was not significantly influenced by tree fern presence (F1,12 = 2.1, p = 0.2) or restoration status (F1,12 = 0.4, p = 0.5).

The abundances and species richness of native plant groups differed across site types (Table 2 and Table 3). Seedling abundances were not significantly influenced by tree fern presence (F1,12 = 0.2, p = 0.7) or restoration status (F1,12 = 0.02, p = 0.9). Rarefied native seedling richness was significantly influenced by the interaction between tree fern presence and restoration status (F1,11 = 5.6, p < 0.05). Post hoc results showed that tree ferns negatively affected rarefied seedling richness restored sites (z = 2.1, p < 0.05) but had no significant effect at unrestored sites (z = −1.3, p = 0.2). Furthermore, restoration status did not significantly influence rarefied seedling richness when tree ferns were present (z = −1.7, p = 0.1) or absent (z = −1.1, p = 0.3).

Table 3.

Mean (±standard deviation) native species abundance, richness and rarefied richness for each plant group and site type. Our plant groups were tree ferns, seedlings, saplings, trees, ground ferns and epiphytes. Site types were based on restoration status (restored, unrestored) and tree fern presence (with, without). The mean tree fern basal areas (m2 ha−1) per site type are also presented.

Native sapling abundances were not significantly influenced by tree fern presence (z = 0.04, p = 0.8) or restoration status (z = 2.1, p = 0.1). Rarefied native sapling richness was significantly influenced by the interaction between tree fern presence and restoration status (F1,11 = 6.9, p < 0.05). Sapling richness was positively affected by tree fern presence at unrestored sites (z = −2.4, p < 0.05) but not at restored sites (z = 0.9, p = 0.4). In comparison, restoration status did not significantly influence rarefied sapling richness when tree ferns were present (z = −1.5, p = 0.2) or absent (z = −0.6, p = 0.8).

Native tree abundances (i.e., woody trees excluding tree ferns) were significantly higher at restored sites (F1,12 = 5.6, p < 0.05) but were not affected by tree fern presence (F1,12 = 0.9, p = 0.7). There was no statistically significant difference in rarefied tree species richness with tree fern presence (F1,12 = 0.3, p = 0.6) or restoration status (F1,12 = 0.04, p = 0.8).

Ground fern abundance was significantly higher at sites with tree ferns (F1,12 = 15.1, p < 0.01) but did not differ with restoration status (F1,12 = 1.3, p = 0.4). Likewise, rarefied ground fern richness was strongly positively influenced by tree fern presence (F1,12 = 24.7, p < 0.001) but was not significantly affected by restoration status (F1,12 = 0.01, p = 0.8). While neither tree ferns nor restoration status had a statistically significant effect on epiphyte abundance at the α = 0.05 level, tree ferns were associated with increased epiphyte abundance (F1,12 = 3.3, p = 0.9). Furthermore, rarefied native epiphyte richness was significantly higher at sites with tree ferns (F1,12 = 13.2, p < 0.001) but was not affected by restoration status (F1,12 = 2.5, p = 0.1).

3.2. Community Composition

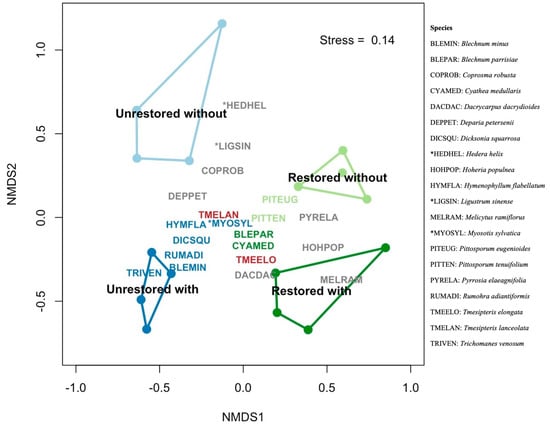

Distinct plant communities were associated with our site types, further supporting our first two hypotheses. Our permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) models found significant differences in total vascular plant composition (native and exotic species) across all pairwise comparisons except for between restored sites with and without tree ferns (see Figure 4 and Table A1). Native plant composition also differed significantly among five of the six pairwise comparisons across all levels of our factorial design (Table S3, Supplementary Materials).

Figure 4.

Nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) ordination of plant community composition by abundances. Convex hulls are drawn around the four site types: restored with tree ferns (dark green), restored without tree ferns (light green), unrestored with tree ferns (dark blue), and unrestored without tree ferns (light blue). The ordination achieved a “fair” stress score of 0.14. The coloured dots represent the sites, and six–letter codes represent the indicator or abundant species (see legend for scientific names). An asterisk denotes an exotic species. Species colours represent indicator species of the site types: restored with tree ferns (dark green), restored without tree ferns (light green) and unrestored with tree ferns (dark blue). The species in grey are eight of the most abundant species, and the species in red (2) represent indicators of unrestored sites with tree ferns that are also abundant species. The ten most abundant species accounted for 62% of the mean relative abundance.

The abundant species (i.e., the ten most dominant species overall) at restored sites were Dacrycarpus dacrydioides, Melicytus ramiflorus J.R.Forst. & G.Forst., Hoheria populnea A.Cunn. and Pyrrosia elaeagnifolia (Bory) Hovenkamp. In contrast, the abundant species at sites with tree ferns were Deparia petersenii (Kunze) M.Kato, Tmesipteris lanceolata P.A.Dang. and Tmesipteris elongata P.A.Dang. Three abundant species were associated with sites without tree ferns, a native shrub (Coprosma robusta Raoul) and two exotic species (Hedera helix L. and Ligustrum sinense Lour.).

An indicator species analysis identified 12 species for three site types (Table A2). Unrestored sites with tree ferns were associated with the most indicator species (8), including ground ferns (Blechnum minus (R.Br.) Ettingsh.), tree ferns (Dicksonia squarrosa), epiphytic ferns (Tmesipteris elongata, T. lanceolata, Trichomanes venosum R.Br., Rumohra adiantiformis (G.Forst.) Ching and Hymenophyllum flabellatum Labill.) and one exotic herb (Myosotis sylvatica Hoffm.). No indicator species were associated with unrestored sites without tree ferns, likely because of their depauperate assemblages. Species with high fidelity to restored sites with tree ferns were Blechnum parrisiae Christenh. and Cyathea medullaris. In comparison, indicator species of restored sites without tree ferns were Pittosporum eugenioides A.Cunn. and Pittosporum tenuifolium Sol. ex Gaertn.

3.3. Community Structure

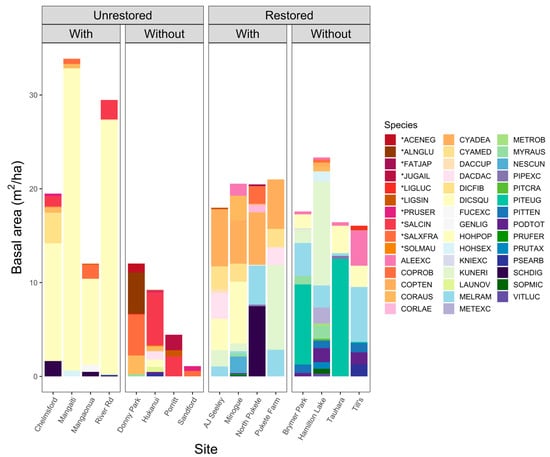

We investigated differences in plant community structure among our site types using the basal area of stems greater than 2.5 cm DBH (see Supplementary Materials, Table S4 for complete model statistics). GLMs revealed that total basal area (native trees, exotic trees and tree ferns) was significantly higher at sites with tree ferns (F1,12 = 8.1, p < 0.05) but did not differ with variations in restoration status (F1,12 = 0.002, p = 1.0). The native tree basal area was significantly higher at restored sites (F1,12 = 8.4, p < 0.05) but did not vary significantly with tree fern presence (F1,12 = 0.7, p = 0.7). Furthermore, the tree fern basal area was significantly higher at sites with tree ferns (F1,12 = 17.2, p < 0.01), but restoration status had no significant effect (F1,12 = 0.4, p = 0.5). Finally, the exotic tree basal area did not vary significantly with the tree fern presence (F1,12 = 3.8, p = 0.1) or restoration status (F1,12 = 1.0, p = 0.3).

Figure 5 shows the basal areas for individual plant species across sites. Unrestored sites with tree ferns covered the highest average basal area (25.7 ± 12.2 m2 ha−1), dominated by Dicksonia squarrosa (82%). Unrestored sites without tree ferns covered the lowest average basal area (9.0 ± 6.8 m2 ha−1), with only a few exotic trees, such as Salix cinerea L. and Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn. (Table S5, Supplementary Materials). Basal areas were more similar among restored sites, whether tree ferns were present (18.5 ± 3.3 m2 ha−1) or absent (18.4 ± 3.4 m2 ha−1). While unrestored sites with tree ferns were dominated by D. squarrosa (light yellow bars), restored sites with tree ferns achieved higher basal areas of Cyathea dealbata and C. medullaris (orange bars).

Figure 5.

Tree and tree fern basal areas (m2 ha−1) of vegetation plots measured in Hamilton, New Zealand. The 16 plots were assigned to our four site types based on restoration status (restored, unrestored) and the presence of tree ferns (with, without). An asterisk preceding the six-letter codes denotes an exotic species. Scientific and common names associated with the six-letter species codes are provided in Table A3.

3.4. Environmental Predictors of Plant Communities

We examined potential environmental predictors of individual plant groups and total native species richness across our site types. The GLM results identified environmental predictors correlated with plant community composition (Table 4). Rarefied native richness (Table 4) was positively influenced by the tree fern basal area (z = 4.4, p < 0.001) and the restoration age (z = 4.4, p < 0.001) but negatively influenced by the maximum tree height (z = −3.0, p < 0.01) and the average slope (z = −1.6, p = 0.1). Rarefied exotic species richness was negatively associated with tree fern basal area, but the relationship was not statistically significant at an alpha level of 0.05 (z = −1.6, p = 0.1, Table 4).

Table 4.

Generalised linear model results investigating environmental predictors of native rarefied richness, exotic rarefied richness and rarefied richness per plant group (i.e., seedling, sapling, tree, ground fern and epiphyte richness). Environmental predictors were standardised (i.e., centred on the mean and scaled to unit variance). Incidence rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are provided. Statistically significant p-values at α = 0.05 are in boldface.

The environmental predictors influencing rarefied native species richness differed among individual plant groups. Table 4 shows that restoration age positively affected seedling (z = 3.7, p < 0.001) and tree species richness (z = 4.1, p < 0.001). Native sapling species richness (Table 4) was also positively influenced by restoration age (z = 3.8, p < 0.001) but was negatively influenced by maximum height (z = −2.5, p < 0.05) and average slope (z = −2.1, p < 0.05). Although not statistically significant at an alpha level of 0.05, tree fern basal area positively affected rarefied native sapling richness (Table 4). Table 4 also shows strong positive relationships between the tree fern basal area and rarefied ground fern (z = 4.0, p < 0.001) and epiphyte richness (z = 5.7, p < 0.001).

Our distance-based redundancy analysis (dbRDA) found significant correlations between tree fern basal area and restoration age, with differences in plant community composition by abundances across sites (Figure A2). Variation partitioning revealed the amount of variation (R2 = 0.29) in plant community composition explained by tree fern basal area and restoration age, with slightly more variation explained independently by the tree fern basal area (F1,13 = 3.2, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.15) than the restoration age (F1,13 = 3.3, p < 0.01, R2 = 0.14). There was no shared variation explained by these two environmental variables.

4. Discussion

We identified distinct plant communities associated with restoration status and tree fern presence. Higher native plant richness at restored sites without tree ferns was partially driven by increased plant abundances, with more diverse woody pioneer communities. In contrast, the presence of tree ferns at unrestored sites supported higher native species richness with more diverse epiphyte and ground fern assemblages. Most epiphytes (approximately 90%) were on tree ferns, and 65% of ground ferns only occurred in plots with tree ferns. Tree ferns provide a thick root mantle and fibrous substrate with high moisture retention that is conducive to epiphyte establishment [58]. Hence, tree ferns appear to augment native species richness by providing a suitable habitat for these plant groups. These results highlight the strong association between tree ferns, epiphytes and ground ferns, three functionally diverse plant groups that contribute to ecosystem processes [59,60]. Additionally, increased basal areas (i.e., an indicator of biomass) at our sites with tree ferns showed the significant effect that tree ferns can have on plant community structure and composition. Our results, therefore, show that the presence of tree ferns can enhance native species richness and the functioning of urban ecosystems via richer epiphyte and ground fern assemblages.

4.1. Community Assembly and Succession

We found a range of differences in plant composition among our site types, suggesting that early-arriving tree ferns significantly impact plant community composition and assembly [23]. The most abundant tree fern at unrestored sites was Dicksonia squarrosa, while Cyathea medullaris and C. dealbata were more abundant at restored sites. Restored sites with tree ferns also had fewer native seedlings, saplings and trees (i.e., angiosperms and conifers), signalling competitive relationships among these groups, which is consistent with previous research [61]. Where priority effects lead to tree ferns establishing first, a positive feedback loop may prevent other species from establishing and occasionally inhibit successional processes [14,62,63]. Our results suggest that tree ferns do not inhibit some shade-tolerant species and, with the natural or assisted arrival of these species, may assist the successional pathway towards broadleaved-conifer forest.

In urban restoration, enrichment planting (i.e., planting late-successional species in the understory of pioneer communities) is critical for replacing short-lived pioneers with long-lived species [35]. Little to no enrichment planting has been undertaken at our restored sites, and few late successional species were recorded in any of our site types. Species such as Dacrydium cupressinum, Alectryon excelsus Gaertn. and Hedycarya arborea J.R.Forst. & G.Forst. have been sparsely planted at some restored sites.

We did not directly investigate successional pathways using remeasurement of tree fern communities over time; however, community composition on our chronosequence may signal potential pathways. Tree ferns are primarily considered mid–late successional species, although species including Dicksonia squarrosa and Cyathea medullaris can dominate early successional stages. Higher native sapling species richness at our unrestored sites with tree ferns suggests that tree ferns may assist species regeneration. Furthermore, our sites with tree ferns supported some shade-tolerant broadleaf species (e.g., Schefflera digitata J.R.Forst. & G.Forst.), which aligns with a previous study where tree ferns did not inhibit shade-tolerant species [28]. Putative pathways following these communities include the development of a broadleaf understory after 40 years and conifer-broadleaf forest after 80–100 years [12,30,64].

4.2. Study Limitations

Whilst our results suggest that tree ferns can act as ecological filters, thereby altering plant community composition, our study faced some limitations. First, our statistical power was limited by the sites available that met the criteria for site selection (i.e., n = 4 per site type; Table S1), which could have reduced our ability to statistically identify differences (i.e., increased chance of Type II errors); however, in many cases, our analyses detected significant (α = 0.05) differences among the treatments. Second, species richness is expected to increase with time. Although we controlled for plot restoration age (i.e., the time since native planting began) in our statistical analyses as a covariate, the age of sites dominated by tree ferns was difficult to verify because, unlike the woody species we dated, they do not exhibit annual growth rings. Third, our study design was a mensurative experiment, and sites with tree ferns may be confounded by other variables. While our results signal the importance of retaining extant tree ferns, experimentally planting them at restoration sites and observing long-term successional trajectories would provide additional insights into their role in shaping community composition.

4.3. Implications for Urban Ecological Restoration

Standard restoration practice focuses on restoring pioneer trees and shrubs, such as Leptospermum scoparium and Kunzea ericoides, without recognising the ecological value of pioneer tree ferns. Pioneer trees are favoured because they are easily sourced and affordable. In contrast, ferns are rarely available from restoration nurseries. Pioneer trees also grow faster than tree ferns. In two decades, Kunzea ericoides can reach 7 m in height [29], compared to Cyathea medullaris (2.3 m) and Dicksonia squarrosa (1 m) [65].

Our results highlight the need to protect extant tree ferns, as they can augment native species richness and enhance opportunities for urban restoration projects. Although monospecific colonies can arrest succession [14], we found tree fern communities to support higher native species richness, providing a habitat for ground ferns and epiphytes, which are both poorly represented functional groups in urban forests [66,67]. Extant tree fern stands also provide the advantage of a native-dominated canopy from the outset of restoration projects. Establishing and maintaining a canopy is critical to the success of ecological restoration projects [68]. A developed canopy slows the establishment and growth of light-demanding invasive plants that compete with native species [69]. However, a canopy can take several decades to reinstate, requiring ongoing labour to release native trees from exotic species that persist in high light levels. Our sites with tree ferns were associated with reduced exotic species abundance. Therefore, using extant tree ferns, rather than replacing them with pioneer trees, could advance restoration progress.

A bespoke approach, planting pioneers best suited to the site conditions, should be employed in urban restoration. Determining which pioneer species are appropriate for a site should be guided by their ecology (e.g., growth strategy and habitat). Kunzea ericoides and Leptospermum scoparium generally colonise drier sites [28], and tree ferns occur on hillslopes and gullies or depressions. Dense stoloniferous thickets of Dicksonia squarrosa may restrict tree regeneration but support diverse epiphyte communities. These stands may require manipulation (i.e., reducing the cover or density of dominant canopy species to increase diversity) to prevent monospecific, self-perpetuating thickets and allow tree regeneration or enrichment planting without diminishing epiphyte diversity. In contrast, monopodial Cyathea medullaris and C. dealbata may require less thinning. Studies manipulating tree fern stands have primarily included binary treatment groups [16] or frond thinning trials [61], but there is a lack of long-term research measuring community composition along a gradient of tree fern densities.

We identified some potential environmental predictors of our distinct plant communities, including restoration age and tree fern basal area. Slope and the maximum canopy height also negatively affected native species richness, possibly due to reduced soil moisture on steeper sites and inadequate enrichment planting beneath tall pioneer trees. Furthermore, tree fern basal areas positively influenced native epiphyte and ground fern species richness and negatively affected exotic species richness.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our results highlight the ecological value of extant tree ferns in augmenting native species richness, supporting functional groups like ground ferns and epiphytes and potentially suppressing exotic species by providing an early canopy. Incorporating pioneer tree ferns into restoration practice will encourage the diversification of plant communities and the range of species and life forms they support. Tree fern basal area and restoration age significantly contributed to our distinct plant communities, but further research on epiphyte functional traits and environmental drivers is necessary to better understand epiphyte–host and epiphyte–environment relationships. Long-term quantitative research on how tree fern density influences community composition is also needed to determine thresholds for maximising indigenous plant diversity in urban ecosystems. Overall, our study suggests a need to reconsider current restoration practices that often overlook or remove tree ferns in favour of faster-growing pioneer trees.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f16091498/s1, Table S1: Site age and history of the sixteen vegetation plots; Figure S1: Vegetation plot design (200 m2); Figure S2: Variation partitioning of the effects of tree fern basal area and restoration age on community composition; Table S2: Generalised linear model results testing the effect of tree fern presence and restoration status on total native abundances, rarefied species richness, exotic plant abundances and rarefied richness; Table S3: Pairwise comparisons of native vascular plant communities among the four site types; Table S4: Generalised linear model results testing the effect of tree fern presence and restoration status on total basal area (exotic trees, native trees and tree ferns), native woody tree basal area, tree fern basal areas and exotic tree basal area; Table S5: Three leading dominant trees or tree ferns for each site type.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.C.R. and B.D.C.; methodology, H.C.R.; software, H.C.R.; validation, H.C.R., F.J.B. and B.D.C.; formal analysis, H.C.R. and F.J.B.; investigation, H.C.R.; resources, B.D.C.; data curation, H.C.R.; writing—original draft preparation, H.C.R.; writing—review and editing, H.C.R., F.J.B. and B.D.C.; visualisation, H.C.R.; supervision, F.J.B. and B.D.C.; project administration, H.C.R.; funding acquisition, B.D.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the People, Cities & Nature research programme, which was funded by the Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment (MBIE) Endeavour Grant [UOWX2101] from the New Zealand government and a George Mason Charitable Trust PhD scholarship.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Thanks are extended to Fergus Chinnery, René Devenish and Amanda Hassan for their field assistance and to Hamilton City Council for providing access to our study sites in Hamilton.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DBH | Diameter at breast height |

| dbRDA | Distance-based redundancy analysis |

| GLM | Generalised linear model |

| HCC | Hamilton City Council |

| NMDS | Nonmetric multidimensional scaling |

| PCaN | People, Cities & Nature Programme |

| PERMANOVA | Permutational multivariate analysis of variance |

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Rarefaction and extrapolation curves for each plot. Data were extrapolated to 200 individuals to investigate whether sampling intensity satisfied the expected native species richness. Colours represent the four study groups: unrestored with tree ferns (dark blue), unrestored without (light blue), restored with (dark green) and restored without (light green).

Figure A2.

Redundancy analysis (RDA) of the effect of restoration age and tree fern basal area (BA) on influential species (six-letter codes). Our study groups were based on restoration status (restored, unrestored) and the presence of tree ferns (with, without). Species colours represent indicator species of the study groups: restored sites with tree ferns (dark green), restored sites without tree ferns (light green) and unrestored sites with tree ferns (dark blue). Species in grey are eight of the most abundant species, and red species (2) represent indicator species of unrestored sites with tree ferns that are also abundant species. These ten most abundant species accounted for 62% of the mean relative abundance. An asterisk denotes an exotic species.

Appendix B

Table A1.

Pairwise comparisons of vascular plant communities (native and exotic abundances) among the four site types using a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) and accounting for restoration age (i.e., years since native plantings started) as a covariate.

Table A1.

Pairwise comparisons of vascular plant communities (native and exotic abundances) among the four site types using a permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) and accounting for restoration age (i.e., years since native plantings started) as a covariate.

| Group 1 | Group 2 | F-Value | R2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrestored without | Restored with | 2.23 | 0.47 | <0.05 |

| Unrestored without | Restored without | 2.25 | 0.47 | <0.05 |

| Unrestored with | Restored with | 2.58 | 0.51 | <0.05 |

| Unrestored with | Unrestored without | 4.61 | 0.43 | <0.05 |

| Unrestored with | Restored without | 4.68 | 0.65 | <0.05 |

| Restored with | Restored without | 0.87 | 0.13 | 0.68 |

Table A2.

Indicator species associated with three of our site types. Indicator values represent the strength of the relationship between the species abundances and the site type; values closer to 1 signal stronger associations. An asterisk denotes an exotic species.

Table A2.

Indicator species associated with three of our site types. Indicator values represent the strength of the relationship between the species abundances and the site type; values closer to 1 signal stronger associations. An asterisk denotes an exotic species.

| Site Type | Species | Indicator Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unrestored sites with tree ferns | Tmesipteris elongata | 1.00 | <0.01 |

| Tmesipteris lanceolata | 0.92 | <0.01 | |

| Trichomanes venosum | 0.96 | <0.01 | |

| Blechnum minus | 0.93 | <0.01 | |

| Rumohra adiantiformis | 0.87 | <0.05 | |

| Dicksonia squarrosa | 0.89 | <0.01 | |

| Hymenophyllum flabellatum | 0.87 | <0.05 | |

| * Myosotis sylvatica | 0.87 | <0.05 | |

| Restored sites with tree ferns | Blechnum parrisiae | 0.87 | <0.05 |

| Cyathea medullaris | 0.87 | <0.05 | |

| Restored sites without tree ferns | Pittosporum eugenioides | 0.97 | <0.01 |

| Pittosporum tenuifolium | 0.80 | <0.05 |

Table A3.

Scientific names associated with the six-letter species codes presented in the trees and tree fern basal area facet plot (see Figure 5). Common and family names are also provided.

Table A3.

Scientific names associated with the six-letter species codes presented in the trees and tree fern basal area facet plot (see Figure 5). Common and family names are also provided.

| Status | Six-Letter Code | Scientific Name | Common Name | Family |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exotic | ACENEG | Acer negundo | Box elder | Sapindaceae |

| ALNGLU | Alnus glutinosa | Alder | Betulaceae | |

| FATJAP | Fatsia japonica | Fatsia | Araliaceae | |

| JUGAIL | Juglans ailantifolia | Japanese walnut | Juglandaceae | |

| LIGLUC | Ligustrum lucidum | Tree privet | Oleaceae | |

| LIGSIN | Ligustrum sinense | Chinese privet | Oleaceae | |

| PRUSER | Prunus serrulata | Japanese cherry | Rosaceae | |

| SALCIN | Salix cinerea | Grey willow | Salicaceae | |

| SALXFRA | Salix ×fragilis | Crack willow | Salicaceae | |

| SOLMAU | Solanum mauritianum | Woolly nightshade | Solanaceae | |

| Native | ALEEXC | Alectryon excelsus | Tītoki | Sapindaceae |

| COPROB | Coprosma robusta | Karamū | Rubiaceae | |

| COPTEN | Coprosma tenuicaulis | Hukihuki | Rubiaceae | |

| CORAUS | Cordyline australis | Tī kōuka | Asparagaceae | |

| CORLAE | Corynocarpus laevigatus | Karaka | Corynocarpaceae | |

| CYADEA | Cyathea dealbata | Ponga | Cyatheaceae | |

| CYAMED | Cyathea medullaris | Mamaku | Cyatheaceae | |

| DACCUP | Dacrydium cupressinum | Rimu | Podocarpaceae | |

| DACDAC | Dacrycarpus dacrydioides | Kahikatea | Podocarpaceae | |

| DICFIB | Dicksonia fibrosa | Whekī-ponga | Dicksoniaceae | |

| DICSQU | Dicksonia squarrosa | Whekī | Dicksoniaceae | |

| FUCEXC | Fuchsia excorticata | Kōtukutuku | Onagraceae | |

| GENLIG | Geniostoma ligustrifolium | Hangehange | Loganiaceae | |

| HOHPOP | Hoheria populnea | Houhere | Malvaceae | |

| HOHSEX | Hoheria sextylosa | Houhere | Malvaceae | |

| KNIEXC | Knightia excelsa | Rewarewa | Proteaceae | |

| KUNERI | Kunzea ericoides | Kānuka | Myrtaceae | |

| LAUNOV | Laurelia novae-zelandiae | Pukatea | Atherospermataceae | |

| MELRAM | Melicytus ramiflorus | Māhoe | Violaceae | |

| METEXC | Metrosideros excelsa | Pōhutukawa | Myrtaceae | |

| METROB | Metrosideros robusta | Northern rātā | Myrtaceae | |

| MYRAUS | Myrsine australis | Red mapou | Primulaceae | |

| NESCUN | Nestegis cunninghamii | Black maire | Oleaceae | |

| PIPEXC | Piper excelsum | Kawakawa | Piperaceae | |

| PITCRA | Pittosporum crassifolium | Karo | Pittosporaceae | |

| PITEUG | Pittosporum eugenioides | Tarata | Pittosporaceae | |

| PITTEN | Pittosporum tenuifolium | Kōhūhū | Pittosporaceae | |

| PODTOT | Podocarpus totara | Tōtara | Podocarpaceae | |

| PRUFER | Prumnopitys ferruginea | Miro | Podocarpaceae | |

| PRUTAX | Prumnopitys taxifolia | Mataī | Podocarpaceae | |

| PSEARB | Pseudopanax arboreus | Whauwhaupaku | Araliaceae | |

| SCHDIG | Schefflera digitata | Patē | Araliaceae | |

| SOPMIC | Sophora microphylla | Kōwhai | Fabaceae | |

| VITLUC | Vitex lucens | Pūriri | Lamiaceae |

References

- Heino, M.; Kummu, M.; Makkonen, M.; Mulligan, M.; Verburg, P.H.; Jalava, M.; Räsänen, T.A. Forest loss in protected areas and intact forest landscapes: A global analysis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, 0138918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, P.G.; Slay, C.M.; Harris, N.L.; Tyukavina, A.; Hansen, M.C. Classifying drivers of global forest loss. Science 2018, 361, 1108–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güneralp, B.; Seto, K.C. Futures of global urban expansion: Uncertainties and implications for biodiversity conservation. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 014025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeland, S.; Moretti, M.; Amorim, J.H.; Branquinho, C.; Fares, S.; Morelli, F.; Calfapietra, C. Towards an integrative approach to evaluate the environmental ecosystem services provided by urban forest. J. For. Res. 2019, 30, 1981–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepczyk, C.A.; Aronson, M.F.; La Sorte, F.A. Cities as sanctuaries. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2023, 21, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Environment Programme. On World Cities Day, UNEP Announces 19 Cities to Restore Nature’s Rightful Place in Urban Areas. Available online: www.unep.org/technical-highlight/world-cities-day-unep-announces-19-cities-restore-natures-rightful-place-urban (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Chazdon, R.L. Chance and determinism in tropical forest succession. Trop. For. Community Ecol. 2008, 1, 384–408. [Google Scholar]

- Dávila-Hernández, G.; Meave, J.A.; Muñoz, R.; González, E.J. A flash in the pan? The population dynamics of a dominant pioneer species in tropical dry forest succession. Popul. Ecol. 2024, 67, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St. Martin, P.; Mallik, A.U. Alternate successional pathway yields alternate pattern of functional diversity. J. Veg. Sci. 2019, 30, 461–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadotte, M.W. The interacting influences of competition, composition and diversity determine successional community change. J. Ecol. 2023, 111, 1670–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, D.C.; Clarkson, B.D. Tree seedling survival depends on canopy age, cover and initial composition: Trade-offs in forest restoration enrichment planting. Ecol. Restor. 2018, 36, 52–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyse, S.V.; Wilmshurst, J.M.; Burns, B.R.; Perry, G.L. New Zealand forest dynamics: A review of past and present vegetation responses to disturbance; and development of conceptual forest models. N. Z. J. Ecol. 2018, 42, 87–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coomes, D.A.; Allen, R.B.; Bentley, W.A.; Burrows, L.E.; Canham, C.D.; Fagan, L.; Wright, E.F. The hare; the tortoise and the crocodile: The ecology of angiosperm dominance; conifer persistence and fern filtering. J. Ecol. 2005, 93, 918–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.R.; Landau, F.H.; Velazquez, E.; Shiels, A.B.; Sparrow, A.D. Early successional woody plants facilitate and ferns inhibit forest development on Puerto Rican landslides. J. Ecol. 2010, 98, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, M.M.; Walker, L.R.; Mehltreter, K. An invasive tree fern alters soil and plant nutrient dynamics in Hawaii. Biol. Invasions 2013, 15, 355–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, A.S.; Norton, D.A.; Carswell, F.E. Tree fern competition reduces indigenous forest tree seedling growth within exotic Pinus radiata plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 359, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKelvey, P.J. Forest colonisation after recent volcanicity at West Taupo. N. Z. J. For. 1953, 6, 435–438. [Google Scholar]

- Wardle, P. The kahikatea (Dacrycarpus dacrydioides) forest of south Westland. Proc. N. Z. Ecol. Soc. 1974, 21, 62–71. [Google Scholar]

- Smale, M.C.; Beveridge, A.E.; Pardy, G.F.; Steward, G.A. Selective logging in podocarp/tawa forest at Pureora and Whirinaki. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 1987, 17, 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Norton, D.A. Seedling and sapling distribution patterns in a coastal podocarp forest; Hokitika Ecological District; New Zealand. N. Z. J. Bot. 1991, 29, 463–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, B.R.; Smale, M.C. Changes in structure and composition over fifteen years in a secondary kauri (Agathis australis)-tanekaha (Phyllocladus trichomanoides) forest stand; Coromandel Peninsula; New Zealand. N. Z. J. Bot. 1990, 28, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoghue, S.; Turner, P.A. A review of Australian tree fern ecology in forest communities. Austral Ecol. 2022, 47, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, R.C.; Klimas, S.; Carlsen, M. Low-trunk epiphytic ferns on tree ferns versus angiosperms in Costa Rica. Biotropica 2003, 35, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.R.; Sharpe, J.M. Ferns; disturbance and succession. In Fern Ecology; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 177–219. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, K.; Mendieta-Leiva, G.; Zotz, G. Host specificity in vascular epiphytes: A review of methodology; empirical evidence and potential mechanisms. AoB Plants 2015, 7, plu092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrão, R.; Sampaio-e-Silva, T.; Kortz, A.R.; Magurran, A.; Matos, D.M. An endangered tree fern increases beta-diversity at a fine scale in the Atlantic Forest Ecosystem. Flora 2017, 234, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, J.M.; Morales, N.S.; Burns, B.R.; Perry, G.L. The hare; tortoise and crocodile revisited: Tree fern facilitation of conifer persistence and angiosperm growth in simulated forests. J. Ecol. 2020, 108, 969–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, J.M.; Perry, G.L.; Lee, W.G.; Schwendenmann, L.; Burns, B.R. Pioneer tree ferns influence community assembly in northern New Zealand forests. N. Z. J. Ecol. 2018, 42, 18–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boffa Miskell Limited. The Manuka and Kanuka Plantation Guide. Available online: www.trc.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Guidelines/Land-infosheets/Manuka-plantation-guide-landcare-April2017.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Blaschke, P.M. Vegetation and Landscape Dynamics in Eastern Taranaki Hill Country. Ph.D. Thesis, Victoria University, Wellington, New Zealand, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- McLeary, W.H. A Study of the Gully Systems of the Waikato Basin with Particular Reference to Those in and Surrounding the City of Hamilton: A Research Study. Diploma Dissertation, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand, 1972. Available online: https://researcharchive.lincoln.ac.nz/entities/publication/ba9447f2-2bbc-4490-b43c-199557d9ac4d (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Clarkson, B.D.; Kirby, C.L. Ecological restoration in urban environments in New Zealand. Ecol. Manag. Restor. 2016, 17, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, G.H.; Ignatieva, M.E.; Meurk, C.D.; Earl, R.D. The re-emergence of indigenous forest in an urban environment; Christchurch; New Zealand. Urban For. Urban Green. 2004, 2, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, B.D.; Bylsma, R.J. Restoration planting in urban environments. Indigena (Journal of the Indigenous Forest Section of New Zealand Farm Forestry Association), 7–10 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace, K.J.; Clarkson, B.D. Urban forest restoration ecology: A review from Hamilton; New Zealand. J. R. Soc. N. Z. 2019, 49, 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, B.D.; McGowan, R.; Downs, T.M. In Proceedings of the Hamilton Gullies Workshop. Hamilton, New Zealand, 29–30 April 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Da Fonseca, G.A.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, W.M. Ecological Regions and Districts of New Zealand; Department of Conservation: Wellington, New Zealand, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. Climate Data and Activities. Available online: https://niwa.co.nz/education-and-training/schools/resources/climate (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Rogers, H.C.; Clarkson, B.D. Restoration strategies for three Dacrycarpus dacrydioides (A. Rich.) de Laub.; kahikatea remnants in Hamilton City; New Zealand. Forests 2022, 13, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, H.C.; Clarkson, B.D. Epiphyte-host relationships of remnant and recombinant urban ecosystems in Hamilton; New Zealand: The importance of Dicksonia squarrosa (G. Forst.) Sw.; whekī. N. Z. J. Bot. 2025, 63, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, D.B.; Wehi, P.M.; Clarkson, B.D. Evaluating restoration success in urban forest plantings in Hamilton, New Zealand. Urban Habitats 2011, 6. Available online: http://www.urbanhabitats.org/v06n01/hamilton_full.html (accessed on 12 September 2025).

- Planting a Lasting Urban Forest. Available online: www.peoplecitiesnature.co.nz/publications (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Hurst, J.M.; Allen, R.B. A Permanent Plot Method for Monitoring Indigenous Forests: Field Protocols; Manaaki Whenua-Landcare Research: Lincoln, New Zealand, 2007; Available online: https://nvs.landcareresearch.co.nz/Content/PermanentPlot_FieldProtocols.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2024).

- Breitwieser, I.; Heenan, P.J. Flora of New Zealand Online. 2023. Available online: www.nzflora.info (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria. Available online: www.R-project.org (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.6–4. Available online: http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (accessed on 13 September 2024).

- Hsieh, T.C.; Ma, K.; Chao, A. iNEXT: An R package for rarefaction and extrapolation of species diversity (Hill numbers). Methods Ecol. Evol. 2016, 7, 1451–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenth, R.V. Least-squares means: The R package lsmeans. J. Stat. Softw. 2016, 69, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, P.; Gallagher, E.D. Ecologically meaningful transformations for ordination of species data. Oecologia 2001, 129, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricotta, C.; Podani, J. On some properties of the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity and their ecological meaning. Ecol. Complex. 2017, 31, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cáceres, M.; Jansen, F.; De Caceres, M.M. Package’ indicspecies’. Indicators 2016, 8, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Legendre, P.; Anderson, M.J. Distance-based redundancy analysis: Testing multispecies responses in multifactorial ecological experiments. Ecol. Monogr. 1999, 69, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borcard, D.; Legendre, P. All-scale spatial analysis of ecological data by means of principal coordinates of neighbour matrices. Ecol. Model. 2002, 153, 51–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borcard, D.; Legendre, P.; Avois-Jacquet, C.; Tuomisto, H. Dissecting the spatial structure of ecological data at multiple scales. Ecology 2004, 85, 1826–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, F.G.; Legendre, P.; Borcard, D. Forward selection of explanatory variables. Ecology 2008, 89, 2623–2632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres-Neto, P.R.; Jackson, D.A.; Somers, K.M. Giving meaningful interpretation to ordination axes: Assessing loading significance in principal component analysis. Ecology 2003, 84, 2347–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehltreter, K.; Flores-Palacios, A.; García-Franco, J.G. Host preferences of low-trunk vascular epiphytes in a cloud forest of Veracruz, Mexico. J. Trop. Ecol. 2005, 21, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, M.E.; Woods, C.L. A case for studying biotic interactions in epiphyte ecology and evolution. Perspect. Plant Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2022, 54, 125658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo-Schmidt, L.; Currano, E.D.; Dunn, R.E.; Gjieli, E.; Pittermann, J.; Sessa, E.; Gill, J.L. Ferns as facilitators of community recovery following biotic upheaval. BioScience 2024, 74, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, J.M.; Perry, G.L.; Burkhardt, T.; Burns, B.R. Forest seedling community response to understorey filtering by tree ferns. J. Veg. Sci. 2018, 29, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidlich, E.W.; Nelson, C.R.; Maron, J.L.; Callaway, R.M.; Delory, B.M.; Temperton, V.M. Priority effects and ecological restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2021, 29, e13317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Breugel, M.; Bongers, F.; Norden, N.; Meave, J.A.; Amissah, L.; Chanthorn, W.; Dent, D.H. Feedback loops drive ecological succession: Towards a unified conceptual framework. Biol. Rev. 2024, 99, 9282011949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, B.D. Ecological restoration in Hamilton City. In Proceedings of the Greening the City, Christchurch, New Zealand, 21–24 October 2003; Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture: Lincoln, New Zealand, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bystriakova, N.; Bader, M.; Coomes, D.A. Long-term tree fern dynamics linked to disturbance and shade tolerance. J. Veg. Sci. 2011, 22, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landeros-López, J.G.; Krömer, T.; Gómez-Díaz, J.A.; Velázquez-Rosas, N.; Carvajal-Hernández, C.I. Influence of Microclimatic Variations on Morphological Traits of Ferns in Urban Forests of Central Veracruz, Mexico. Plants 2025, 14, 1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarquin-Pacheco, M.B.; Armenta-Montero, S.; Contreras-López, J.; Carvajal-Hernández, C.I. Urban forests as habitats for vascular epiphytes and allied terrestrial plants. Urban Ecosyst. 2025, 28, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auckland Council. Te Haumanu Taiao-Pānuitia Ngā Aratohu. 2024. Available online: https://www.tiakitamakimakaurau.nz/protect-and-restore-our-environment/te-haumanu-taiao-restoring-natural-environment/te-haumanu-taiao-guide/ (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Martin, P.H.; Canham, C.D.; Marks, P.L. Why forests appear resistant to exotic plant invasions: Intentional introductions; stand dynamics; and the role of shade tolerance. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).