1. Introduction

The Earth is experiencing a biodiversity crisis, which has sparked urgent global calls for the protection of the world’s oceans and terrestrial ecosystems [

1]. Over the past century, countries have carried out practical explorations to varying degrees based on their resource endowments and fundamental national conditions. Through this process, the concept of nature conservation and management models has continuously evolved and developed, gradually accumulating into a rich system of experiences in national park construction [

2,

3,

4]. In many countries, the establishment of national parks is regarded as a crucial strategy for mitigating the adverse impacts of external pressures on biodiversity [

5,

6,

7]. Nevertheless, the various stringent regulatory measures implemented in national parks may force residents in surrounding communities to engage in illegal hunting, logging, and over-exploitation of resources to make a living, exacerbating the contrast between ecological protection and community development [

8,

9]. As a result, the conflict between ecological protection goals and the livelihood development of residents continues to escalate, becoming one of the main obstacles restricting the improvement of national park management efficiency [

10,

11,

12,

13].

The impact of the management and construction of national parks on the livelihoods of local residents has received widespread attention in recent years. From a global perspective, due to differences in national conditions and park characteristics in various countries, a diverse range of impact situations has emerged. Existing studies have shown that, due to factors such as regional economic development levels and management systems, the impact of national parks on residents’ household income and community development varies significantly. On the one hand, in terms of developed countries, numerous studies have found that national parks promote income growth by transforming residents’ household income structures [

3,

5,

14,

15]. In many countries, park construction has driven the rise in ecotourism and supporting service industries, optimized community participation management models, and created new income sources for community residents [

16,

17]. Taking Yellowstone National Park as an example, the surge in tourist numbers has directly improved the prosperity of industries, such as accommodation, catering, and guide services. Some residents have obtained stable rental income by operating homestays [

18,

19,

20]. Japan’s current national park system focuses on the provision of cultural ecosystem services, such as recreational opportunities. The protected landscape concept emphasizes the relationship between nature, livelihoods, and communities, which contributes to the development of the community economy [

21]. Australia’s Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park and Germany’s Bayerischer Wald National Park benefited economically by collaborating with local communities to develop characteristic tourism projects. This model, which integrates culture with tourism, not only enriches tourists’ travel experience but also provides substantial economic returns to community residents [

22,

23,

24]. Additionally, a large number of studies have indicated that the construction of national parks has promoted the improvement of infrastructure and public services. For instance, in some national parks in Canada, such as Banff, the government has increased investment in infrastructure, which has not only enhanced the convenience of community life but also provided strong support for the economic development of the community [

25,

26].

On the other hand, in some developing countries, the establishment and management measures of national parks have had varying impacts on their community development. For example, Serengeti National Park in Tanzania and some national parks in Kenya have adopted co-management arrangements, as well as promoted the construction and renovation of community schools and medical facilities through collaboration with local governments, directly improving residents’ educational attainment and health security levels [

3,

27,

28]. Additionally, a case study of Manu Biosphere Reserve in Peru indicates that supporting indigenous communities’ contributions, empowering their environmental stewardship and avoiding a shift towards intensive agriculture often applied by immigrant groups, are critical to fulfilling the conservation role of national parks and improving social and economic development [

29]. Brazil’s Iguaçu National Park is currently facing substantial impacts from illegal hunting, fishing and palm-heart extraction, and although local illegal actors profit from it, this approach is not sustainable [

30]. However, many studies have also shown that the protection measures and institutional deficiencies of national parks have had a variety of negative impacts on local communities due to the demand for economic development in developing countries. For example, the transportation problems related to inadequate infrastructure construction have had a negative impact on the tourism industry of Kruger National Park in South Africa, hindering the development of local communities [

31]. Further, traditional livelihood patterns have been impacted. In Kenya’s Maasai Mara National Reserve, in order to protect the ecological environment within the park, the grazing areas of the Maasai people have been unreasonably reduced, restricting their traditional nomadic lifestyle [

32]. As a result, Maasai residents, whose main source of income is animal husbandry, are facing the challenge of reduced income. In addition, traditional agricultural production has also been restricted in some national parks. For example, to protect water sources or biological habitats, some arable land has been included in protected areas, and the use of modern agricultural production materials, such as chemical fertilizers and pesticides, has been prohibited, resulting in a decline in crop yields, thus directly affecting income [

8,

33]. For families whose arable land and forest land have been adjusted due to policies, the imperfect ecological compensation mechanism—such as low compensation standards and delayed payment of compensation—also has a negative impact on household income [

34,

35]. Furthermore, in countries such as Nepal, during the construction of national parks, due to unbalanced interest distribution, different community residents may encounter uneven distribution of benefits when participating in tourism development, ecological protection, and other projects, thereby intensifying internal conflicts [

17,

34,

36].

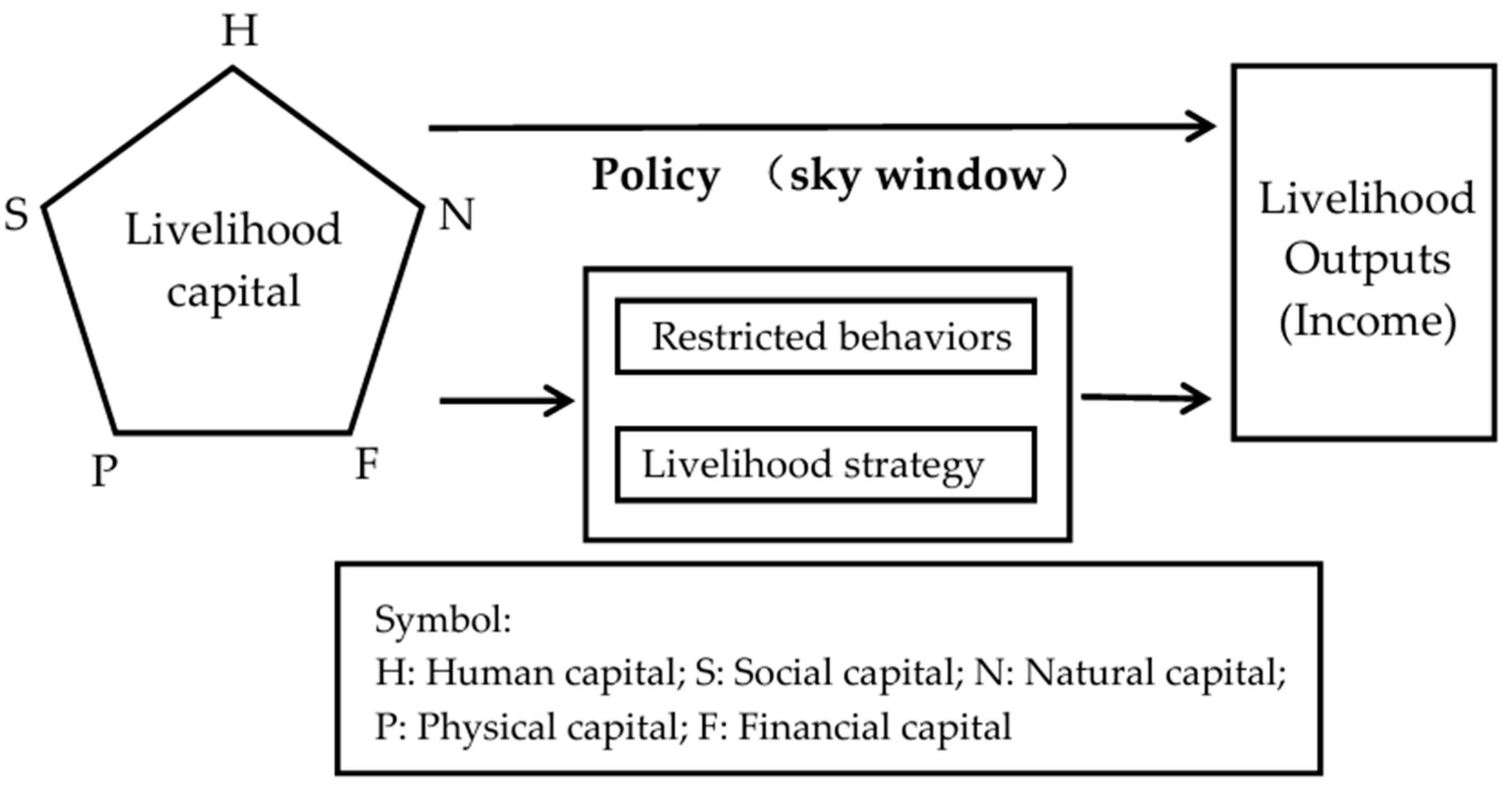

As a typical developing country, the original intention of establishing national parks is to protect biodiversity. The distribution of national parks in China is uneven, but most of them are located in economically underdeveloped areas. Due to the heavy reliance of local residents on natural resources for their production activities, there is a contradiction between environmental protection and community development. This realistic background prompted China to make efforts to improve the construction and management of national parks. Since the establishment of the first batch of five national parks in 2021, China has promoted high-quality development through high-level protection and actively explored new models for the construction of the national park system. In addition to ecological compensation mechanisms and community co-management models, China proposed a new management policy known as the “sky window” policy in 2019, which is an important means of resolving the conflict between ecological protection and community development in the integration and optimization of natural protected areas in China. Its essence is to adjust the boundaries of protected areas and remove land parcels that conflict with protection goals (such as built-up areas, villages, and farmland) from the boundary range, while keeping the geographical space within the protected area [

37,

38]. However, since the launch of national spatial planning and the integration and optimization of national nature reserves, with national parks serving as the main body, the topic of the “sky window” policy has highly attracted the focus of various sectors of society and is even considered controversial. Many studies have analyzed the impact of the “sky window” policy on mitigating ecological protection and sustainable community development from a theoretical perspective. The Chinese Ministry of Natural Resources and other management departments have emphasized that it is extremely necessary to include the “sky window” in the unified monitoring and scientific control scope of ecological protection red lines [

39]. Applying the “sky window” policy within national parks to preserve farmland, residential communities, mineral resource areas, or reserve development zones will enable the implementation of ecological protection and control policies, meet the relevant interests of original residents and rights holders, and reserve greater space for future development [

40]. On the contrary, some scholars have argued that the “sky window” policy has turned national parks into a sieve, which is likely to trigger new livelihood risks, thereby eliminating their protective significance [

41,

42].

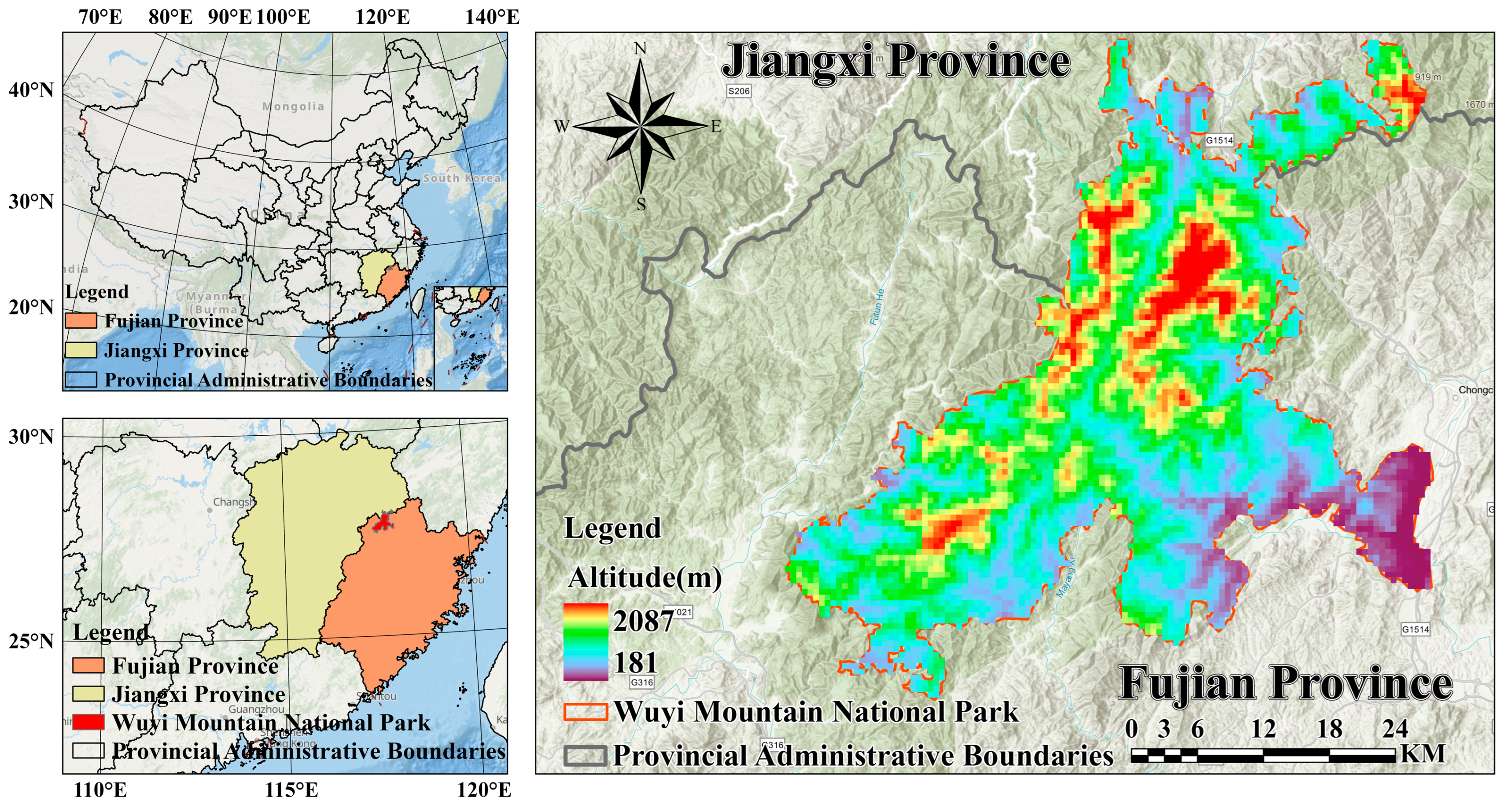

Wuyi Mountain National Park (WMNP) is one of the first batches of officially established national parks in China. It is not only a global human and biosphere reserve but also a national park under the World Natural and Cultural Heritage list [

43], and it has been widely studied. It is generally believed that at the beginning of the construction of WMNP, the conflict between humans and nature remained quite severe [

42]. Ecotourism has introduced many benefits to local communities. Measures such as ecological forest protection compensation and easement management are also pioneering initiatives of WMNP [

44]. However, research has shown that local communities are still dissatisfied with some management practices of the national park, especially when faced with resource usage restrictions [

38]. Regarding the “sky window” policy, community feedback has been mixed. Therefore, research methods for coordinating the relationship between ecological protection and sustainable community development through effective policies and measures are an important issue.

There are still some research gaps worth amending when examining the most relevant studies on the impact of the “sky window” policy on the welfare of residents in national park communities. Firstly, recent research has mainly examined the potential impact of the policy on local communities from a theoretical perspective, lacking systematic quantitative analyses. The analysis results based on empirical data can reveal the impact and effectiveness of the “sky window” policy, which facilitates the adjustment and optimization of the policy. Secondly, although many studies have analyzed the advantages and disadvantages of implementing the “sky window” policy, few have focused on the impact of this policy on the income level of community residents. Thirdly, the potential mechanism of the impact of the policy on household income in national park communities remains to be explored, which is of great significance for implementing more targeted policies.

This study contributes to the research on the effective management of national parks, community welfare improvement, and sustainable development in developing countries. The contributions of this study are multiple in nature. Firstly, the impact of the “sky window” policy on the household income of communities in Wuyi Mountain National Park was quantitatively assessed for the first time; the findings have strong practical value and innovation. Secondly, the relevant mechanisms of the impact of the “sky window” policy on residents’ income were discussed, providing more targeted policy recommendations for the sustainable development of the community. Finally, our findings enrich the relevant research on the effectiveness of administrative measures with respect to adjustments of the boundaries of national parks, and we provide experience and practices for other developing countries to manage their national parks.

The rest of this article is divided into the following sections.

Section 2 provides a literature review and the conceptual framework.

Section 3 introduces the methodology, including sampling and data collection, variables, and model specification.

Section 4 presents the results of descriptive analyses and empirical results from DID and PSM models.

Section 5 presents the discussion and policy implications.

Section 6 provides our conclusions.

5. Discussion

The “sky window” policy is regarded by national parks as an effective ecological governance tool for protecting the natural environment, and its implementation has intensified against the backdrop of ecological redline adjustments [

38]. However, an overemphasis on ecological protection goals while neglecting the sustainability of community development essentially fails to truly realize the government’s vision of the harmonious coexistence of humans and nature. By quantitatively analyzing farmers’ livelihood outcomes, this study systematically evaluates the impact of the “sky window” policy on farmers’ total income in Wuyi Mountain National Park. The “sky window” policy implemented in Wuyi Mountain National Park has been observed to result in a reduction in farmers’ incomes. This result may be explained by various factors, as shown through analysis of the data in the previous sections and the in-depth interviews with important interviewees, such as management departments and village cadres.

5.1. There Is a Structural Contraction in Resource Utilization Rights

Although the geographical space of “window” communities remains within the national park, the policy adjustment of “being excluded from the national park boundary” deprives them of the flexibility in resource utilization that they previously enjoyed within the original protected area [

37,

38]. Although the “sky window” policy theoretically relaxes certain restrictions, the livelihood activities traditionally relied upon by these communities (such as understory planting and traditional breeding) are, in practice, subject to dual constraints, resulting in a decline in their income. This reduction may be caused by the relaxation of planting restrictions, which has allowed farmers to expand and intensify their agricultural production. Furthermore, such industries are characterized by high initial investments, long payback periods, and substantial market risks, which may result in short-term income downturns. Further, as their geographical space still belongs to the national park, resource development activities must meet higher ecological thresholds (e.g., pollution control, scale limitations), which reduces the profit margins of the original production models [

41,

42,

44]. Furthermore, after being excluded from the boundaries of the national park, some communities are no longer included in the ecological compensation and industrial support systems of the national park (such as special subsidies and technical training), resulting in an increase in resource acquisition costs (e.g., agricultural input procurement, production licensing) without a corresponding increase in returns.

5.2. The Household Income Is Influenced by the Discontinuity Effect and Lagging Supporting Measures in Livelihood Transition

As mentioned earlier, “window” communities are typically characterized by “a strong dependence on natural resources and a weak economic foundation” [

41,

42]. The period from 2017 to 2023 coincided with the institutional reform stage of the national park, During this period. After the implementation of the “sky window” policy, the original livelihood models of the communities that relied on national park resources (such as conservation-compatible agriculture and tourism-supporting services) were weakened due to policy adjustments. Simultaneously, new alternative livelihood models (such as non-agricultural employment and market-oriented industries) have been slow to develop due to the lack of supporting measures, including vocational training and credit services, resulting in a sharp reduction in residents’ income channels [

75]. When residents’ farmlands were excluded from the protected area, the government failed to provide timely and effective guidance on agricultural transformation and financial support. Many residents lack training in ecological tourism services, and the area’s underdeveloped tourism infrastructure fails to attract a sufficient number of tourists, resulting in extremely limited income from the tourism industry [

38,

42]. Furthermore, the ecological compensation mechanism, a crucial support measure, has not been effectively implemented in the national park. The traditional livelihood model of the “window” community was damaged and lacks new livelihood models, ultimately resulting in a decline in income.

5.3. Imperfect Laws Resulted in a Lack of Protection of Rights and Interests

Currently, there are still several areas in the legal system of national parks in China that need to be improved. This not only hinders the protection of the rights and interests of residents in park communities but also directly affects their economic income status [

76,

77]. Firstly, there are ambiguous areas in current laws and regulations regarding the definition of core rights, such as residents’ land rights and resource utilization rights. In the process of promoting the “sky window” policy, residents have always lacked clear legal standards as a basis for judging whether their land and resources have been reasonably delineated for protection and whether their legitimate rights and interests have been fully protected. For example, when some residents’ homesteads or contracted land is included in the adjustment scope, due to the unclear definition of the land acquisition process and compensation standards in the law, residents are often prone to being passive and unable to obtain economic compensation that matches their losses [

78]. Secondly, there is no clear legal regulation on the mechanism for coordinating interests between national park management agencies and community residents. In the process of policy implementation, management agencies often overlook the development demands of community residents due to excessive focus on ecological protection goals [

42]. When residents experience a decline in income due to protection policies, they often lack accessible legal channels to safeguard their rights, and they encounter numerous legal barriers when exploring new sources of income, which limits their potential for income growth.

5.4. The Marginalization of Market Access and Value Realization Indirectly Affected the Welfare of Residents in National Park Communities

Upon being excluded from the protected area’s boundary, products from window communities (such as agricultural products and handicrafts) lose the premium brand associations, such as “National Park Origins”, and unified marketing channels (e.g., national-park-led e-commerce platforms) [

79]. The community also loses the brand effect of the national park, directly affecting the development of the community’s ecological tourism industry [

38,

41,

42]. At the same time, as their geographical space remains within the national park, their production activities must bear additional costs for ecological compliance (such as environmental certification). However, they are unable to share the market resources of the national park, resulting in damage to welfare benefits. In addition, due to not being under the jurisdiction of national parks, local communities are often prone to the dilemma of weak local leadership, resulting in a lack of development vitality and financial support.

5.5. The Severe Impact of COVID-19 on the Income of Residents in National Park Communities

Communities in the national park are highly reliant on ecotourism and its derivative services. During the pandemic, the closure of scenic spots and a sharp decrease in tourist flow directly led to the shutdown of homestays, tour guide unemployment, and the breakdown of related income chains [

80]. Simultaneously, the community’s characteristic agricultural products are mostly sold directly through tourism channels. The pandemic disrupted offline transactions, while logistical restrictions hindered online sales, resulting in unsold and overstocked agricultural products and heavy losses for farmers. Handicraft production and ecological experience programs that rely on national park resources also came to a complete halt, exacerbating the already simplistic income structure. In addition, pandemic prevention and control measures increased operational costs, while the slow recovery of tourist flows after reopening kept residents’ income depressed, affecting even their basic livelihoods [

81,

82].

The findings of this study have profound policy implications. Given the short duration of the “sky window” policy’s implementation and its insufficient operational timeframe, many supporting measures remain underdeveloped, resulting in a short-term decline in income. Nevertheless, from a long-term perspective, there is ample room for optimizing policy design, which will, in turn, contribute to income-level improvements.

In the future, efforts should primarily focus on the following aspects. First, laws and regulations governing national park construction should be further improved. During legislative revisions, the scope, standards, and procedures of the “sky window” policy should be clarified, with clear definitions of areas suitable for such measures and the ecological, social, and economic conditions required. For instance, in relevant regulations such as the National Park Law, detailed provisions should be formulated for the “sky window” in specific scenarios, including permanent basic farmland and artificial commercial forests. It is also necessary to clarify the management subject and responsibilities of window communities. At the same time, a dynamic assessment mechanism should be established to conduct regular reviews of the policy effects of the “sky window”, with timely adjustments carried out based on changes in the ecological environment of national parks and the development needs of local communities. Furthermore, the alignment between different regulations should be strengthened to ensure that the “sky window” policy is coordinated and unified within the regulatory framework, including territorial spatial planning and ecological protection redline management, avoiding contradictions and conflicts and thereby enhancing the overall effectiveness of the policy.

In addition, from the perspective of the residents, the national park should facilitate income improvement through four approaches: First, the national park should strengthen cooperation with local communities by establishing a normalized collaboration mechanism that includes management agencies, community representatives, and ecological/planning experts. Priority can also be given to providing positions such as forest rangers and guides to jointly develop ecological products and feedback profits, thus building a benefit sharing model. Second, a platform for realizing the value of ecological products should be established. For example, community handicrafts and organic agricultural products can be incorporated into the national park’s brand certification system and marketed through unified e-commerce platforms and cultural and creative tourism stores. Third, support for livelihood transitions should be enhanced by providing targeted training tailored to residents’ different skill levels, such as homestay management and ecological agriculture techniques, which could be accompanied by microcredit and entrepreneurship subsidies to reduce barriers to transitions. Furthermore, it is necessary to establish a long-term interest linkage mechanism, allocating a certain proportion of tourism revenue to community development funds for residents’ dividends and public service improvement; this would further improve the franchising of national parks, and the participation of community residents in park management, cleaning, and other operations could be prioritized to ensure a stable source of income.

6. Conclusions

This study employed the DID model to quantitatively evaluate the impact of the “sky window” policy on the income levels of community farmers in the context of national park construction. The theoretical significance of this study lies in two aspects: on the one hand, it enriches the existing literature on the impact of the “sky window” policy in national parks and fills some gaps in this field of research; on the other hand, it expands the research scope of the sustainable livelihood framework and offers a brand-new research perspective for the expanded application of this theory in the field of national parks. The major conclusions of this study are as follows.

The demarcation of window communities in Wuyi Mountain National Park exerted a statistically significant negative impact on farmers’ total household income at the 10% significance level. Specifically, compared with non-window communities, the total household income of farmers in window communities decreased by CNY 0.106. The demarcation of window communities in the national park also exerted significant negative impacts on both the agricultural and non-agricultural income of farmers’ households.

The “sky window” policy relaxed restrictions on households’ understory planting and breeding activities within the national park, resulting in a decline in their income, which may be due to the relaxation of planting restrictions, which allowed farmers to intensify their agricultural production. However, such industries are characterized by high initial investments, long payback periods, and substantial market risks, which may result in short-term income downturns. On the other hand, the “sky window” policy had no significant impact on household income through part-time activities.

The “sky window” policy had a significant negative impact on the income of non-party-member households, further illustrating the crucial role of human capital in improving income levels. Furthermore, the “sky window” policy significantly reduced the income levels of households with large savings. The policy also had a significant negative impact on the income of households operating on relatively large land areas, which may be attributed to the fact that it allows residents to access more natural resources, leading to a decrease in their enthusiasm for non-agricultural production, thus resulting in a single channel for increasing income and ultimately lowering their income levels. Additionally, the policy had a greater impact on young and middle-aged families, resulting in a decrease in their household income. Due to the implementation of the “sky window” policy, young adults are more inclined to stay in the local area, reducing the diversified strategy of working outside for their livelihood, which makes the income structure more singular and leads to a decrease in income.

In the future, we recommend the following for improving policy implementation in national parks: First, the laws and regulations on the construction of national parks should be improved. Second, a dynamic evaluation mechanism should be established. In addition, coordination between different regulations should be strengthened to ensure that the “sky window” policy is coordinated and unified within a regulatory framework. From the perspective of residents, income growth can be achieved through the following measures: establishing a platform for realizing the value of ecological products, enhancing support for livelihood transformation, establishing a long-term interest linkage mechanism, and further improving the concessionary operation mechanism of national parks to secure a stable source of income.

We acknowledge that this study has shortcomings. First, the survey focused only on Wuyi Mountain National Park and lacks empirical data from other national parks, which imposes certain limitations. Additionally, the data analyzed is retrospective and may have a certain degree of subjectivity, leading to limitations in the research conclusions. Moreover, our research lacks detailed information on the livelihood strategies employed by local communities to offset income losses; this information could have increased the depth of the study. Furthermore, we only conducted short-term surveys on two sets of data. The results are limited due to various factors, such as insufficient infrastructure and policy support in the short term. A long-term investigation is necessary and will be of great value in understanding the possible changes in household income over time. In response to these two shortcomings, we need to enrich the questionnaire content further, conduct long-term surveys, and comprehensively explore the results in the future in order to provide more targeted insights for management authorities.