1. Introduction

Forest tourism has become an increasingly prominent form of nature-based tourism, valued for its ability to deliver physical renewal, psychological restoration, and meaningful engagement with natural environments [

1]. Where urbanization and daily stress continue to rise, forests stand out as destinations that offer tranquility, biodiversity, and recreational opportunities [

2]. These unique qualities position forests as more than just ecological resources; they serve as spaces where individuals can recover from stress, enhance their well-being, and enrich their lifestyles [

3,

4]. Consequently, understanding the determinants of traveler satisfaction in forest tourism is essential for both advancing scholarly knowledge and guiding destination management strategies that ensure sustainable visitor experiences.

Traveler satisfaction is a core concept in tourism research, often defined as the degree to which travel experiences meet or exceed expectations [

5,

6]. Previous studies have focused primarily on tangible destination attributes such as scenery, infrastructure, and service quality [

7,

8]. While these factors are undeniably important, they offer only a partial explanation for why travelers visiting similar sites report different levels of satisfaction. Satisfaction is a subjective evaluation shaped by the interplay between external features and travelers’ internal states, including their motivations, emotional responses, and personal circumstances [

9]. The Push–Pull Theory of tourism motivation provides a foundational framework for understanding these dynamics, proposing that travel decisions result from internal drives (push factors) interacting with external incentives (pull factors) [

10,

11]. However, most research applying this theory has narrowly examined motivations [

12,

13], often neglecting broader individual-level factors that may influence how motivations are transformed into experiential outcomes.

Recent literature has begun to suggest that lifestyle orientations and physical conditions are critical elements in shaping tourism experiences and satisfaction [

14]. Lifestyle reflects patterns of behavior, values, and preferences that influence the type of travel experiences individuals seek and how they interpret them [

15]. For example, travelers with leisure-oriented lifestyles tend to prioritize restorative and recreational experiences, which may amplify the positive effects of forest environments on satisfaction. Conversely, individuals with work-dominated lifestyles may find it harder to detach from occupational obligations, potentially limiting the perceived restorative value of the trip [

16]. In addition, the traveler’s physical condition also plays a dynamic role in shaping tourism outcomes. Healthy travelers are more capable of engaging with physically demanding or immersive activities, which often leads to deeper emotional connection and higher satisfaction; in contrast, travelers experiencing illness or physical limitations may encounter constraints that restrict their participation, reducing their overall enjoyment even in otherwise favorable settings [

17,

18]. These observations underscore the importance of considering both lifestyle and physical condition as integral factors that interact with motivations to influence satisfaction in forest tourism.

Nowadays, the growing availability of user-generated content presents a valuable opportunity to investigate these factors with greater depth and accuracy [

19]. Online reviews capture travelers’ authentic expressions, including their emotional states, motivations, and evaluations, often in ways that traditional survey methods cannot [

20]. Through linguistic analysis, these narratives provide rich data for understanding how internal factors are reflected in language and how they correspond to satisfaction outcomes. Despite this potential, research systematically linking linguistic cues to satisfaction in forest tourism remains limited. Few studies have used large-scale textual data to examine how motivations, emotional tone, lifestyle orientations, and physical conditions collectively influence traveler satisfaction, leaving a gap in both theory and practice. Therefore, in order to address this gap, the purpose of this study is to examine how travelers’ motivation, lifestyle, and physical condition, identifying through linguistic cues in online reviews, jointly shape satisfaction with forest tourism experiences within a push–pull theoretical framework. Adopting a large-scale text mining approach within a push–pull theoretical framework, this study examines how linguistic cues reflecting from emotional tone, motivational themes, lifestyle orientations, and physical conditions predict traveler satisfaction.

This research provides an integrated understanding of the psychological, physical, and motivational factors that drive forest traveler satisfaction. The findings not only enrich academic theories but also offer actionable insights for destination managers, service providers, marketers, and policymakers seeking to design forest tourism experiences that meet the diverse needs of travelers and promote sustainable destination development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Push–Pull Theory of Tourism Motivation

The Push–Pull Theory offers a foundational framework for understanding the psychological and contextual forces that drive individuals to engage in tourism activities. Originated in social psychology, The Push–Pull Theory was used to explain individual decision-making as influenced by internal drives (push factors) and external incentives or constraints (pull factors) [

21]. Over time, this dual-process framework was adapted across disciplines to analyze human behavior as a dynamic interplay between intrinsic motivations and environmental influences. In the tourism discipline, the traveler’s behavior is also influenced by two distinct but complementary sets of motivations [

10]. The push factors are internal, socio-psychological drivers that compel individuals to travel, such as the desire for rest, relaxation, novelty, self-enhancement, or escape from routine [

22]. In contrast, pull factors are external characteristics of a destination that attract travelers, including natural landscapes, recreational opportunities, cultural appeal, and service infrastructure [

23].

In the context of forest tourism, push motivations often manifest in the form of stress relief, health restoration, emotional renewal, and curiosity-driven exploration [

24,

25]. Forest travelers may seek forests to escape urban environments, to reconnect with nature, or to engage in reflective and recreational experiences [

26]. Meanwhile, forests function as pull destinations due to their aesthetic appeal, biodiversity, tranquility, and opportunities for low-impact activities such as hiking, birdwatching, and nature immersion [

27]. Empirical studies have consistently shown that the alignment between travelers’ push motivations and the destination’s pull characteristics significantly contributes to the success of nature-based travel experiences.

Further refinement of this Push–Pull Theory allows for categorizing motivations into subtypes such as (1) internal variables, such as push motivations, personal values, lifestyle patterns, self-image, and personality traits; (2) external variables, including destination pull factors, situational constraints, marketing strategies, social influences (e.g., family, reference groups), and socio-demographic factors like household roles and group decision-making styles; (3) trip characteristics, referring to elements like travel party size, trip distance, duration, and timing; and (4) experiential factors, encompassing travelers’ emotional states during the trip and their evaluations after the experience [

10]. Understanding these motivational dimensions is critical for examining how they contribute to travelers’ satisfaction within the forest tourism domain.

For instance, lifestyle, as an internal push factor, reflects the values, interests, and behavioral patterns that shape a traveler’s preferences. Individuals with leisure-oriented lifestyles are pushed to travel by intrinsic desires for relaxation and recreation [

28], whereas those with work-dominated lifestyles may be motivated by the need to temporarily detach from social commitment or professional obligations [

29]. As to the individual’s physical condition, good health often acts as a push factor, driving individuals to seek physically engaging or restorative experiences in natural settings, while poor health may either constrain travel or push individuals toward destinations that promise wellness and recovery benefits [

30].

Although previous studies have examined motivational drivers and destination attributes in forest tourism, there has been limited attention to the roles of lifestyle and physical condition. Few studies systematically link these three domains: motivation, lifestyle, and physical condition in shaping forest traveler satisfaction. This gap is critical because existing research tends to isolate these factors, leaving unanswered how they interact to influence satisfaction outcomes. Addressing this omission allows for a more integrated framework that captures both psychological and contextual dimensions of forest tourism experiences.

2.2. Forest Traveler Satisfaction

Traveler satisfaction is a central outcome variable in tourism research, referring to the extent to which individuals’ expectations and needs are fulfilled during and after their travel experience [

31]. Within the forest tourism context, satisfaction reflects not only the evaluation of services and facilities but also the emotional, physical, and psychological outcomes derived from interacting with nature [

7,

32]. Forest environments provide visitors with opportunities for tranquility, scenic enjoyment, physical activity, and emotional renewal, making them uniquely positioned to fulfill a wide range of traveler expectations [

33].

A growing body of research highlights that natural destinations such as forests promote positive emotional states and contribute to well-being, which are key antecedents of satisfaction [

34]. Forest travelers often report feelings of peace, relaxation, and inspiration, especially when their experience aligns with their initial motivations [

35]. Indicated by Komppula et al. [

36], travelers who visit forests to escape daily stress typically express higher satisfaction when the destination offers a quiet and uncrowded environment. Similarly, forest travelers seeking nature engagement or physical activity are more satisfied when the destination provides accessible trails, guided tours, or opportunities for wildlife observation [

37].

Several destination attributes have been found to influence forest traveler satisfaction. These include the perceived quality of natural settings (e.g., scenery, biodiversity), service and infrastructure (e.g., cleanliness, signage, amenities), and overall experience quality (e.g., perceived authenticity, sense of immersion). Moreover, emotional responses to the forest environment, such as awe, joy, or reflection, can further reinforce satisfaction levels [

38]. Ultimately, forest traveler satisfaction is the result of a comprehensive assessment of how well the visit fulfills the individual’s initial motivations, needs, and experiential expectations [

8].

2.3. Influence of Motivation, Physical Condition, and Lifestyle on Traveler Satisfaction

The satisfaction of forest travelers is shaped by a combination of psychological motivations [

39], physical condition [

17], and lifestyle orientation [

38]. Among these, motivation is the most proximal determinant, directly influencing travelers’ expectations and how they evaluate their experiences [

39]. When travelers’ push motives, such as the desire to relax, explore, or escape, are effectively addressed by the destination’s pull attributes, satisfaction tends to be higher. For example, travelers seeking reward through peaceful settings are more satisfied when the forest environment is quiet, clean, and conducive to rest [

40]. Those motivated by curiosity or allure are likely to derive greater satisfaction when the site offers novel or aesthetically engaging experiences [

41].

Meanwhile, physical condition plays an equally important role in shaping travelers’ perceptions and overall satisfaction [

17]. Forest tourism, by nature, often requires varying levels of physical exertion, whether in the form of walking trails, engaging in outdoor activities, or participating in wellness programs [

2]. Travelers in good physical health may be more inclined to explore challenging or extensive areas of the forest, which in turn enriches their engagement and satisfaction [

42]. Conversely, visitors facing illness or physical limitations may require accessible facilities, rest areas, or guided support. Satisfaction in such cases depends on whether the destination accommodates their needs and reduces physical strain or discomfort. Importantly, some travelers deliberately seek forest destinations to improve their health or recover from fatigue, which makes the physical condition both a motivator and a moderator of satisfaction [

18].

Lifestyle factors further influence how travelers experience and evaluate forest travel. Individuals differ in their habitual behaviors, values, and preferences, which affect the kinds of travel experiences they seek and how they define satisfaction [

38]. For instance, leisure-oriented individuals often prioritize rest, enjoyment, and personal enrichment, and they tend to be more satisfied with nature-based experiences that support these goals [

43]. On the other hand, individuals with work-dominated lifestyles may use forest travel as a rare opportunity for detachment and mental recovery [

29]. Their satisfaction is more likely when the forest experience provides a clear contrast to their daily routines. Similarly, those with a home-centered lifestyle may prefer structured and low-intensity activities and derive satisfaction from comfort, predictability, and safety [

44]. Collectively, the integration of motivation, physical condition, and lifestyle provides a comprehensive perspective on what determines forest traveler satisfaction. Each factor contributes uniquely to shaping expectations, influencing experience quality, and guiding post-travel evaluations.

3. Method

3.1. Data Collection

This study employed a big data approach to examine the relationship between traveler satisfaction and various influencing factors within the context of national forest tourism. User-generated content was collected from TripAdvisor, a widely used travel review platform known for its extensive repository of traveler experiences. To ensure data relevance and representativeness, the sampling framework was constructed based on the official list of national forests provided by the National Forest Foundation (

https://www.nationalforests.org/our-forests/find-a-forest, accessed on 15 June 2025). This list served as a reference for identifying forest destinations across the United States.

A total of 10,792 individual traveler reviews were retrieved using automated data extraction techniques. Each review record included structured attributes (e.g., rating, date, destination name) and unstructured content (e.g., review text). The dataset spans reviews posted from the earliest available entry for each TripAdvisor page up to the data collection date, ensuring full temporal coverage for all sites. In total, reviews from 125 U.S. national forests were included, providing broad geographic coverage and diverse traveler perspectives. This scope supports the representativeness and generalizability of the findings within the national forest tourism context.

3.2. Data Analysis

Prior to analysis, the data underwent a thorough cleaning process. Duplicates and incomplete entries were removed, and reviews without essential content (e.g., missing review text or satisfaction rating) were excluded. For each forest tourism attraction, all available reviews published on TripAdvisor since the launch of its corresponding page were collected, ensuring comprehensive coverage of the full posting period for each site. The remaining data were subjected to text analysis using LIWC 2022 (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count), a well-established psycholinguistic tool that enables the extraction of psychologically meaningful categories from textual data [

45]. To derive lifestyle, physical condition, motivation indicator, and review tone, we relied on the validated lexical categories included in the LIWC 2022 dictionary, which have been widely applied in psychology, communication, and tourism research. Specifically, the leisure category captures language related to relaxation and recreation, which we interpreted as a leisure-oriented lifestyle; the home category reflects domestic or family-centered expressions, representing a home-oriented lifestyle; and the work category captures occupational or productivity-related terms, indicating a work-oriented lifestyle. Similarly, the health and illness categories were used to represent physical condition, while the reward, risk, curiosity, and allure categories were operationalized as motivational indicators.

The primary analytical method used was Ordered Logit Regression, selected due to the ordinal nature of the dependent variable traveler satisfaction, measured through star ratings. This modeling approach is appropriate for capturing the probability of higher or lower satisfaction levels as a function of categorical and continuous predictors [

46]. Independent variables included review tone, inferred lifestyle category (e.g., leisure-, home-, or work-oriented), indicators of physical condition (e.g., references to health or illness), and motivational themes (e.g., reward, risk, curiosity, and allure). This methodological approach enables a systematic evaluation of how personal and perceptual factors, as reflected in review content, shape reported satisfaction with forest tourism experiences. And the push–pull model on forest traveler satisfaction is presented in

Figure 1.

4. Results

Refer to

Table 1, the descriptive statistics reveal that forest travelers generally report high satisfaction (mean rating = 4.69), with reviews predominantly characterized by a positive tone (mean = 5.66) and minimal negativity (mean = 0.47). Among lifestyle indicators, leisure-oriented language is most prevalent, reflecting the recreational nature of forest visits, while home- and work-related references are infrequent. Physical condition is not a major theme in the reviews, though some mention health (mean = 0.12) and illness (mean = 0.03). Regarding motivation, allure emerges as the most salient factor (mean = 9.58), indicating that natural beauty and emotional appeal strongly influence visitor experiences, while reward, risk, and curiosity are less commonly expressed.

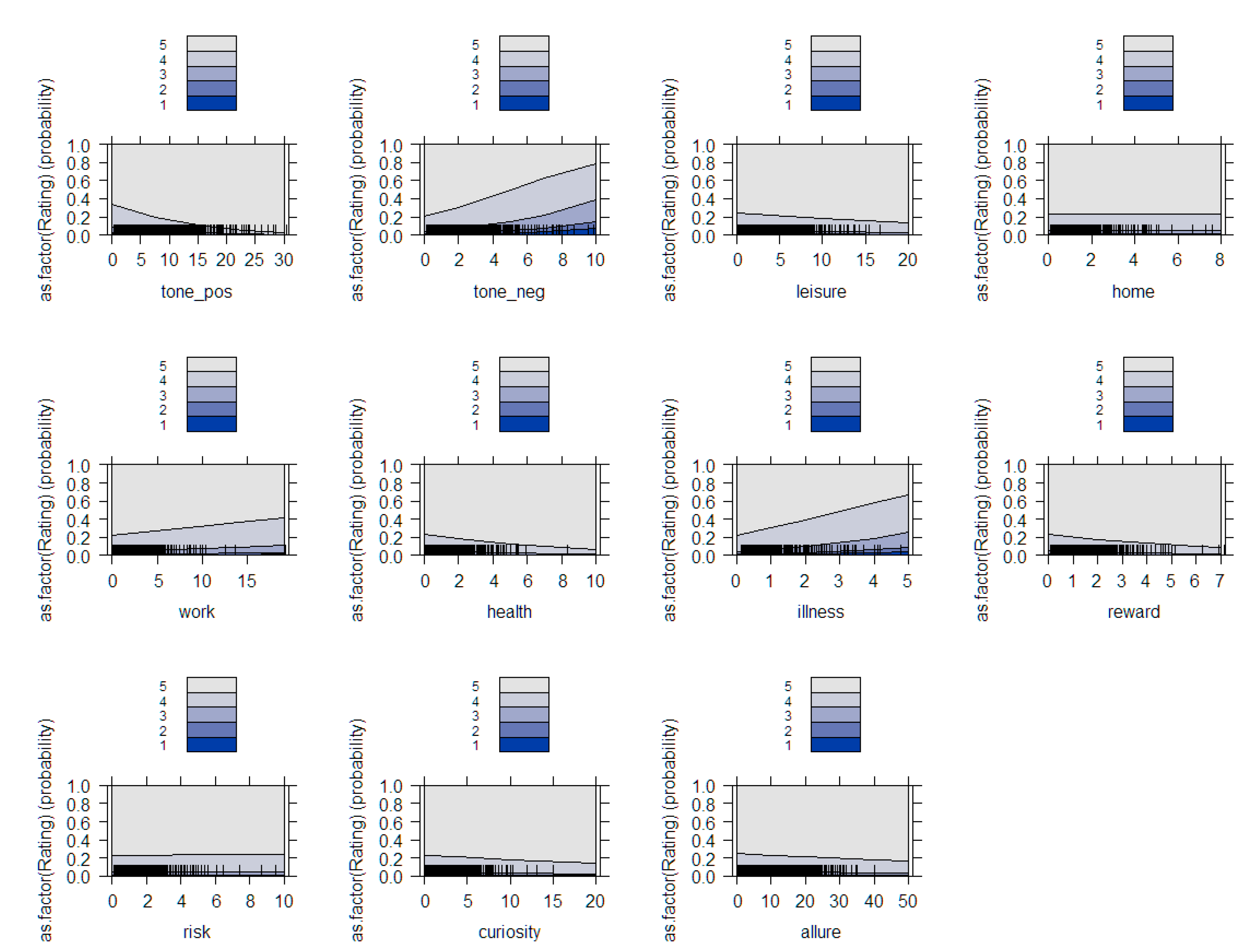

The plots in

Figure 2 show the cumulative probabilities of traveler satisfaction ratings across different explanatory factors. Overall, the figure illustrates that some variables, particularly tone, health, illness, and reward, have noticeable impacts on satisfaction. The clearest effects appear for review tone and physical condition: positive tone and health-related references increase the probability of high satisfaction, while negative tone and illness references decrease it. Lifestyle variables show weaker patterns, with leisure terms modestly raising satisfaction, work references slightly reducing it, and home-related factor showing no effect. Among motivational factors, reward demonstrates a small but positive association with satisfaction, while risk and curiosity have almost no visible influence. Allure shows only a marginally positive trend.

The results of the Ordered Logit Regression (

Table 2) additionally provide several significant predictors of forest traveler satisfaction. Overall, the findings highlight that emotional tone, leisure orientation, physical well-being, and reward motivation are key contributors to higher levels of forest traveler satisfaction.

Among tone variables, positive tone has a strong and significant positive effect (β = 0.0971, p < 0.001, suggesting that positively worded reviews are associated with higher satisfaction ratings. Conversely, negative tone significantly reduces satisfaction (β = −0.2630, p < 0.001). In terms of lifestyle, references to leisure significantly enhance satisfaction (β = 0.0365, p = 0.0032), while home references are not significant, and work references have a marginally negative effect (β = −0.0477, p = 0.0601). For physical condition, expressions related to health are positively associated with satisfaction (β = 0.1380, p = 0.0125), while mentions of illness have a strong negative impact (β = −0.3881, p < 0.001). Regarding motivation, reward-related language significantly boosts satisfaction (β = 0.1622, p = 0.0042), whereas risk and curiosity show no significant influence. The effect of allure is marginally significant (β = 0.0096, p = 0.0581), suggesting a weak positive relationship.

5. Discussion

The results of this study offer meaningful insights into the interplay between linguistic cues and forest traveler satisfaction. First, the emotional tone of reviews demonstrates a clear relationship with satisfaction: positive expressions are significantly associated with higher satisfaction levels, while negative expressions correspond with lower satisfaction. This aligns with prior findings suggesting that emotional valence in narratives serves as a proxy for subjective evaluations [

47]. The positive tone likely reflects fulfilling experiences in natural environments [

48], whereas negative tone may capture unmet expectations, discomfort, or dissatisfaction with service or accessibility [

49]. Recent evidence further supports this relationship, showing that even short-term engagement with natural settings significantly reduces stress and enhances positive affect, thereby strengthening overall satisfaction with nature-based tourism experiences [

50]. This emotional resonance reinforces the idea that destination satisfaction is often constructed and articulated through affective language, which in turn reflects the traveler’s sense of meaning, value, and satisfaction with the destination.

As to the impact of lifestyle, it also makes a difference in tourism satisfaction, affirming that forest visits serve as a space for leisure and mental restoration. Specifically, the home lifestyle, often associated with domestic or routine references, does not exhibit a significant effect, possibly because it contrasts with the escapist nature of forest travel [

51]. Meanwhile, the work lifestyle has a marginally negative association, suggesting that the intrusion of work-related thoughts or responsibilities may diminish the restorative benefits of natural settings, consistent with the concept of psychological detachment as a critical component of successful leisure experiences [

52]. Recent research supports this interpretation, as Zhou et al. [

53] found that leisure involvement significantly enhances perceived health benefits and stress recovery in urban forest parks, while Chang et al. [

54] demonstrated that work-related cognitive intrusions reduce the psychological gains derived from nature exposure. These findings align with our results, indicating that lifestyle orientation conditions the degree to which forest visits provide psychological detachment and emotional restoration. Collectively, these lifestyle cues suggest that the psychological distance from everyday responsibilities is vital in framing satisfaction with forest-based activities.

The consideration of physical condition further supports this restorative narrative. References to health correlate with increased satisfaction, indicating that feeling physically well or engaging in health-related activities (e.g., hiking, fresh air, nature walks) enhances the experience [

55]. This aligns with the discussion of health tourism and green exercise, which posits that physical vitality enhances not only participation but also evaluative judgments of the environment [

56]. In contrast, illness significantly detracts from satisfaction, which may reflect physical discomfort or limitations that reduce enjoyment of various activities [

57]. Illness-related discourse may also represent a heightened sensitivity to physical constraints or negative effects, which influence overall impression formation and satisfaction ratings.

Regarding motivation, travelers expressing reward-oriented motivations, such as achievement, personal gain, or emotional gratification, report higher satisfaction. This implies that forests are perceived as rewarding spaces that fulfill emotional or psychological needs, particularly through symbolic and experiential rewards [

58]. This finding supports push–pull theoretical frameworks, wherein intrinsic motivations (push) interact with destination attributes (pull) to shape overall evaluations [

21]. Interestingly, risk and curiosity do not significantly influence satisfaction, which can be theoretically explained by the restorative and safety-oriented nature of forest tourism. Forest destinations are typically positioned and experienced as low-stimulation, predictable environments designed for relaxation and psychological recovery rather than for high-arousal exploration or thrill-seeking [

59]. Consequently, travelers with stronger novelty-seeking or risk-taking tendencies may find these needs only partially satisfied, which limits the translation of such motivations into higher satisfaction levels.

Moreover, the linguistic patterns in the reviews reflect this alignment, with discourse predominantly emphasizing tranquility, health, and leisure rather than adventure or exploration. This indicates that for most travelers, forests function primarily as restorative spaces that foster emotional well-being rather than as platforms for risk or curiosity fulfillment. The marginally significant effect of allure, which captures fascination or attraction, suggests that while aesthetic or symbolic appeal matters, its impact may be secondary compared to more tangible emotional and health-related factors [

60]. Allure may function as an initial pull factor but does not sustain satisfaction unless accompanied by emotional or experiential reinforcement.

Overall, the findings highlight that forest traveler satisfaction is not merely a function of environmental features but is deeply influenced by the internal emotional state, lifestyle orientation, physical well-being, and motivational context of the traveler. These results underscore the importance of considering psychological and behavioral dimensions in forest tourism research and management.

5.1. Implications

5.1.1. Theoretical Implication

This study provides several theoretical implications for understanding forest traveler satisfaction. First, the findings extend the Push–Pull Theory by revealing that traveler satisfaction is not solely driven by internal motivations and external destination attributes but is also shaped by individual lifestyle orientations and physical conditions. Traditional push–pull frameworks focus on psychological drives and environmental stimuli as independent determinants of travel behavior [

11]. The results show that lifestyle and physical health function as moderating factors that alter how motivations translate into satisfaction. For instance, travelers with leisure-oriented lifestyles derived higher satisfaction from similar forest settings compared to those whose reviews referenced work, indicating that lifestyle filters the impact of pull attributes on perceived benefits. Likewise, the presence of illness weakened satisfaction even in otherwise favorable environments, suggesting that physical state conditions the evaluation of experiences [

61]. These findings broaden the theoretical scope of the Push–Pull Theory by incorporating personal state variables that interact with motivations and destination features to shape post-travel evaluations.

Second, the analysis reinforces the theoretical value of emotional tone as a reliable proxy for subjective tourism experiences. While previous studies associate emotional valence with service evaluations [

62], the current findings provide strong empirical support that emotional tone embedded in natural language is directly linked to satisfaction in forest tourism. Positive tone significantly increased satisfaction, demonstrating that expressions of positive emotion reflect fulfilling psychological outcomes. Conversely, negative tone lowered satisfaction, implying that dissatisfaction often stems from unmet psychological needs or physical discomfort. This evidence enriches tourism literature by validating emotional expressions in user-generated content as a measurable construct that captures subjective well-being and evaluative judgments [

20].

Third, the study refines motivation theory in nature-based tourism by differentiating the effects of specific motivational dimensions on satisfaction. The results indicate that reward-oriented motivations have a strong positive impact, while curiosity and risk do not significantly influence satisfaction. This challenges the assumption that all intrinsic motivations contribute equally to positive evaluations and highlights the context-dependent nature of motivational effects. In restorative forest settings, motivations tied to psychological gain, such as emotional reward or relaxation, are more consequential than those associated with exploration or risk-taking. The marginal effect of allure further suggests that aesthetic appreciation, while valuable, plays a secondary role compared to health-related or emotional fulfillment. This nuanced differentiation advances motivation theory by demonstrating the need to examine how motivational subtypes align with the experiential qualities of specific tourism contexts.

Fourth, the results bridge health psychology and tourism satisfaction research by demonstrating that physical condition is a dynamic determinant of experience quality. Prior studies often treat physical health as a static demographic variable [

63], yet the findings here show that it actively shapes emotional and cognitive appraisals of forest travel. References to health were associated with higher satisfaction, while mentions of illness strongly reduced satisfaction, indicating that bodily states influence both participation in activities and the perceived restorative value of the destination [

64]. This aligns with environmental psychology theories linking physical well-being to restorative benefits in natural environments. By integrating health-related factors into the framework of tourism satisfaction, the study introduces a cross-disciplinary perspective that enriches theoretical models of travel behavior and underscores the critical role of physical state in nature-based tourism research.

5.1.2. Practical Implication

This study offers several practical implications that can guide the management, marketing, and policy development of forest tourism. For forest destination managers, the findings highlight the importance of creating environments that align with travelers’ psychological needs for relaxation and reward. The strong positive impact of leisure orientation and reward motivation suggests that destinations should prioritize tranquil settings, well-maintained trails, and spaces designed for emotional restoration. Facilities that encourage stress relief, such as quiet zones, scenic viewpoints, and opportunities for gentle nature immersion, can enhance the perceived value of forest visits. By catering to these psychological drivers, managers can strengthen travelers’ emotional connection to the destination, leading to higher satisfaction and positive word-of-mouth.

For service providers operating within forest tourism areas, the results emphasize the need to accommodate visitors’ diverse physical conditions. The significant positive effect of health references and the strong negative effect of illness on satisfaction indicate that physical comfort is critical in shaping experiences. Providers should ensure that infrastructure includes accessible paths, resting areas, and health-supportive amenities to meet the needs of visitors with varying physical abilities. Offering guided services or wellness-oriented programs, such as forest therapy walks, can further enhance the experience for those seeking health recovery or physical rejuvenation, reducing barriers for less physically fit travelers while enriching the experience for healthier visitors [

65].

For marketing professionals, the evidence of this study suggests that communication strategies should highlight emotional benefits and rewarding aspects of forest travel rather than focusing solely on adventure or curiosity-driven experiences. The results show that motivations tied to emotional gain exert a stronger influence on satisfaction than curiosity or risk. Marketing messages that emphasize emotional restoration, scenic tranquility, and personal enrichment are likely to resonate more deeply with potential visitors. Furthermore, showcasing testimonials or user-generated content that conveys positive emotional tone can reinforce favorable expectations and increase the likelihood of satisfying experiences.

For policymakers responsible for the sustainable development of forest tourism, the findings underscore the need to integrate health and well-being considerations into planning frameworks. The demonstrated link between physical state and satisfaction suggests that policies should promote accessibility, safety, and wellness-oriented infrastructure in forest destinations. Initiatives that support the development of inclusive trails, health-monitoring facilities, and nature-based rehabilitation programs can enhance the overall value proposition of forests as restorative spaces. By embedding health and psychological well-being into tourism policies, authorities can strengthen the dual role of forests as both recreational and public health assets.

For the broader tourism industry, the study illustrates that user-generated content analysis can serve as a powerful tool for understanding visitor experiences and improving service quality. The clear relationship between linguistic emotional tone and satisfaction validates the use of natural language data as a real-time indicator of traveler perceptions. Industry stakeholders can leverage textual analytics to monitor visitor sentiment, detect emerging issues, and adapt offerings accordingly. This approach enables data-driven decision-making that is responsive to travelers’ evolving psychological and physical needs, ultimately contributing to more satisfying and sustainable tourism experiences.

6. Conclusions

This study advances the understanding of traveler satisfaction in forest tourism by integrating psychological, behavioral, and physical dimensions within a push–pull theoretical framework. Analyzing 10,792 user-generated reviews, the findings demonstrate that emotional tone, lifestyle orientation, physical condition, and motivational factors collectively shape satisfaction outcomes. Positive emotional tone, leisure-oriented language, health references, and reward-driven motivations significantly enhance satisfaction, while negative tone, illness mentions, and work-oriented expressions are associated with diminished evaluations. The absence of significant effects for curiosity and risk, along with the marginal influence of allure, highlights that restorative and emotionally rewarding experiences take precedence over exploratory or thrill-seeking motives in forest travel. These results underscore the value of linguistic indicators in capturing subjective evaluations and provide robust evidence that traveler satisfaction is shaped not only by destination attributes but also by internal states and personal contexts.

Despite these contributions, several methodological limitations should be acknowledged. First, reliance on LIWC-based lexical analysis, while grounded in a validated psycholinguistic framework, may not fully capture the nuanced meanings or cultural contexts embedded in traveler narratives. Second, because the dataset was limited to TripAdvisor users, there is potential sampling bias, meaning the findings may not fully represent all forest visitors. Finally, sentiment and motivation inferred from textual data should be interpreted with caution, as individual expression styles and language preferences can introduce variability. Recognizing these limitations provides important context for interpreting the results and underscores the need for future studies to incorporate qualitative validation, multi-platform datasets, or complementary analytic approaches for deeper insight.

Theoretically, this study extends the push–pull paradigm by positioning lifestyle orientation and physical condition as critical moderators that shape how motivations translate into experiential outcomes, while also validating emotional tone in user-generated content as a reliable proxy for subjective well-being in nature-based tourism contexts. Practically, the findings emphasize the importance for destination managers, service providers, and policymakers to design restorative and inclusive forest environments, accommodate diverse physical conditions, and highlight emotional and health-related benefits in communication strategies. Future research should enrich this framework by integrating longitudinal data, multimodal information sources such as images or physiological indicators, and personality traits to capture more nuanced behavioral patterns. Such efforts will not only refine theoretical models of forest tourism satisfaction but also support evidence-based strategies for sustainable and inclusive destination development.

Future studies could also explore temporal patterns of emotional language and integrate multimodal data sources (e.g., images or biometric feedback) to provide a more holistic understanding of forest tourism experiences. Moreover, forest destination managers may benefit from leveraging affective and motivational cues in digital communications and on-site services to better align offerings with visitor expectations and enhance satisfaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W.; Methodology, J.Z.; Software, J.Z. and Z.H.; Validation, X.W. and Z.H.; Formal analysis, X.W.; Investigation, X.W. and C.Z.; Resources, J.Z.; Data curation, J.Z.; Writing—original draft, X.W. and J.Z.; Writing—review and editing, X.W. and J.Z.; Visualization, X.W.; Supervision, X.W.; Project administration, X.W.; Funding acquisition, X.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department of Education of Guangdong Province (grant number UICR0400019-23), the Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province (Guangdong and Hong Kong Universities “1+1+1” Joint Research Collaboration Scheme), and the Guangdong Planning Office of Philosophy and Social Science (grant number GD25YSG29).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Chenyu Zhao is employed by the company Huatai Life Insurance Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Qiu, M.; Sha, J.; Scott, N. Restoration of visitors through nature-based tourism: A systematic review, conceptual framework, and future research directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H.; Kruger, L.E.; Schultz, C.L.; Henderson, J.R. Key characteristics of forest therapy trails: A guided, integrative approach. Forests 2023, 14, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Thompson, C.W. Human engagement with forest environments: Implications for physical and mental health and wellbeing. In Challenges and Opportunities for the World’s Forests in the 21st Century; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 71–92. [Google Scholar]

- Doimo, I.; Masiero, M.; Gatto, P. Forest and wellbeing: Bridging medical and forest research for effective forest-based initiatives. Forests 2020, 11, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, C.G.Q.; Qu, H. Examining the relationship between tourists’ attribute satisfaction and overall satisfaction. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2009, 18, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engeset, M.G.; Elvekrok, I. Authentic concepts: Effects on tourist satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2015, 54, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, C.; Hao, Y. Effect of the development level of facilities for forest tourism on tourists’ willingness to visit urban forest parks. Forests 2022, 13, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Y.; Luo, F.; Li, H. The impact of aesthetic expectations and aesthetic experiential qualities on tourist satisfaction: A case study of the Zhangjiajie National Forest Park. Forests 2024, 15, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J.; Witlox, F. Travel satisfaction revisited. On the pivotal role of travel satisfaction in conceptualising a travel behaviour process. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2017, 106, 364–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, M.; Li, X.; Sirakaya-Turk, E. Push–pull dynamics in travel decisions. In Handbook of Hospitality Marketing Management; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 412–439. [Google Scholar]

- Soldatenko, D.; Zentveld, E.; Morgan, D. An examination of tourists’ pre-trip motivational model using push–pull theory: Melbourne as a case study. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2023, 9, 572–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, D.; Suhartanto, D. The formation of visitor behavioral intention to creative tourism: The role of push–Pull motivation. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 24, 393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, L.N.; Pham, L.H.; Hoang, T.T.P. Applying push and pull theory to determine domestic visitors’ tourism motivations. J. Tour. Serv. 2023, 14, 136–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, M.; Dias, Á.; Gonçalves, F.; Sousa, B.; Pereira, L. Measuring sustainable tourism lifestyle entrepreneurship orientation to improve tourist experience. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, N.M.; Hem, L.E.; Mehmetoglu, M. Lifestyle segmentation of tourists seeking nature-based experiences: The role of cultural values and travel motives. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33 (Suppl. S1), 38–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, T.; Sharada, V.S.; Tripathi, M.; Basu, R. Towards a Balanced Lifestyle: How Bleisure Travel Is Reshaping Work-Life Balance Among Professionals. In Smart Travel and Sustainable Innovations in Bleisure Tourism; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 149–178. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.H. Effects of cuisine experience, psychological well-being, and self-health perception on the revisit intention of hot springs tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2014, 38, 243–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, J.; Song, J.; Lu, Y. The effects of tourism motivation and perceived value on tourists’ behavioral intention toward forest health tourism: The moderating role of attitude. Sustainability 2025, 17, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wang, X.; Mao, Y. Secrets of More Likes: Understanding eWOM Popularity in Wine Tourism Reviews Through Text Complexity and Personal Disclosure. Tour. Hosp. 2025, 6, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Leung, W.K.; Cheah, J.H.; Ting, H. Exploring the effectiveness of emotional and rational user-generated contents in digital tourism platforms. J. Vacat. Mark. 2022, 28, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiamjanya, S.; Wongleedee, K. International tourists’ travel motivation by push-pull factors and the decision making for selecting Thailand as destination choice. Int. J. Soc. Educ. Econ. Manag. Eng. 2014, 8, 1326–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Sangpikul, A. Travel motivations of Japanese senior travellers to Thailand. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 10, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, R.L.; Elliott, C.L. Scenic routes linking and protecting natural and cultural landscape features: A greenway skeleton. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davari, D.; Jang, S. Travel-based learning: Unleashing the power of destination curiosity. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 396–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.G.; Kim, J.G.; Park, B.J.; Shin, W.S. Effect of forest users’ stress on perceived restorativeness, forest recreation motivation, and mental well-being during COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 6675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammitt, W.E. The relation between being away and privacy in urban forest recreation environments. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 521–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sageena, G.; Kumar, S. Regenerative Tourism Industry: Pathways to Sustainability Amid Gender and Environmental Challenges; Emerald Group Publishing: Leeds, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.; Chiu, W. The role of leisure centrality in university students’ self-satisfaction and academic intrinsic motivation. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2021, 30, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, F. The work-leisure paradigm: The stresses and strains of maintaining a balanced lifestyle. World Leis. J. 2006, 48, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartig, T. Three steps to understanding restorative environments as health resources. In Open Space: People Space; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2007; pp. 183–200. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, J.; Luo, Y. More Than Taste: Effects of Visitor’s Cognitive Appraisal on the Complete Satisfaction of Wine Tourism. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, L.; Campbell, C.; Buckley, R.; Zhu, D.; Yu, H.; Chauvenet, A.; Cooper, M.A. Senses, emotions and wellbeing in forest recreation and tourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2025, 50, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, J.; Dong, X.; Zhai, X.; Shen, J. Rethinking Cultural Ecosystem Services in Urban Forest Parks: An Analysis of Citizens’ Physical Activities Based on Social Media Data. Forests 2024, 15, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Weng, L. The impact of tourists’ perceived value on environmentally responsible behavior in an urban forest park: The mediating effects of satisfaction and subjective well-being. Forests 2024, 15, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkić, J.; Filep, S.; Taylor, S. Shaping tourists’ wellbeing through guided slow adventures. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 2064–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komppula, R.; Konu, H.; Vikman, N. Listening to the sounds of silence: Forest-based wellbeing tourism in Finland. In Nature Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 120–130. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, W.; Meng, H.; Zhang, Z. Analyzing visitors’ preferences and evaluation of satisfaction based on different attributes, with forest trails in the Akasawa National Recreational Forest, Central Japan. Forests 2019, 10, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Han, G.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, J. More than words: Do personality, emotion, and lifestyle matter on the wine tourism? Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N.K.; Woo, E.; Chen, J.S.; Uysal, M. Motivation and involvement as antecedents of the perceived value of the destination experience. J. Travel Res. 2013, 52, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Yao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Dong, J.; Chen, Y. Combined effects of the visual–acoustic environment on public response in urban forests. Forests 2024, 15, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P. Cultural communication in museums: A perspective of the visitors experience. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0303026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karjalainen, E.; Sarjala, T.; Raitio, H. Promoting human health through forests: Overview and major challenges. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2010, 15, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Wang, Y. Social support and travel: Enhancing relationships, communication, and understanding for travel companions. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 26, e2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.L.; Chen, C.L.; Chang, S.J.; Wu, B.S. Home-based intelligent exercise system for seniors’ healthcare: The example of golf croquet. Sports 2023, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, R.L.; Ashokkumar, A.; Seraj, S.; Pennebaker, J.W. The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC-22; University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 2022; Volume 10, pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, M. Determinants of residential satisfaction: Ordered logit vs. regression models. Growth Change 1999, 30, 264–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, J.; Tang, L.R.; Luo, Y. Recommend or not? The influence of emotions on passengers’ intention of airline recommendation during COVID-19. Tour. Manag. 2023, 95, 104675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, J.; Sparks, P. The affective quality of human-natural environment relationships. Evol. Psychol. 2011, 9, 451–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, J. Strategic Customer Service: Managing the Customer Experience to Increase Positive Word of Mouth, Build Loyalty, and Maximize Profits; Amacom: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Avecillas-Torres, I.; Herrera-Puente, S.; Galarza-Cordero, M.; Coello-Nieto, F.; Farfán-Pacheco, K.; Alvarado-Vanegas, B.; Ordóñez-Ordóñez, S.; Espinoza-Figueroa, F. Nature Tourism and Mental Well-Being: Insights from a Controlled Context on Reducing Depression, Anxiety, and Stress. Sustainability 2025, 17, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.B. Routine matters: Narratives of everyday life in families. In Social Conceptions of Time: Structure and Process in Work and Everyday Life; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2002; pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- Luta, D.; Pogrebtsova, E.; Provencher, Y. The wellbeing implications of thinking about schoolwork during leisure time: A qualitative analysis of Canadian university students’ psychological detachment experiences. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 771–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Fan, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, G.; Lan, S. How leisure involvement impacts visitors’ perceived health benefits in urban forest parks: Examining the moderating role of place attachment. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1493422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.-Y.; Liu, T.-Y.; Yen, C.-H. Forest travel activities reduce stress among university students: Evidence from physiological and psychological indicators. Front. Psychol. 2024, 14, 1240499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, I.D.; Wohlfart, T. Walking, hiking and running in parks: A multidisciplinary assessment of health and well-being benefits. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 130, 89–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Chen, X. Research on tourist satisfaction and behavioral intention in ecological health tourism activities in bama, guangxi based on structural equation model. Geoj. Tour. Geosites 2024, 52, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekici, A.; Joseph Sirgy, M.; Lee, D.J.; Yu, G.B.; Bosnjak, M. The effects of shopping well-being and shopping ill-being on consumer life satisfaction. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2018, 13, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, J.; Aspinall, P. The emotional affordances of forest settings: An investigation in boys with extreme behavioural problems. Landsc. Res. 2011, 36, 535–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Miyazaki, Y. Evaluating the relaxation effects of emerging forest-therapy tourism: A multidisciplinary approach. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandua, D. The Influence of Wine on Society; David Sandua: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Maunier, C.; Camelis, C. Toward an identification of elements contributing to satisfaction with the tourism experience. J. Vacat. Mark. 2013, 19, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Martin, D.; Woodside, A.G. Emotions in tourism: Theoretical designs, measurements, analytics, and interpretations. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 1391–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, C.; Delgado, N.; García-Bello, M.Á.; Hernández-Fernaud, E. Exploring crowding in tourist settings: The importance of physical characteristics in visitor satisfaction. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Kralj, A.; Moyle, B.; He, M.; Li, Y. Perceived destination restorative qualities in wellness tourism: The role of ontological security and psychological resilience. J. Travel Res. 2025, 64, 835–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukder, M.B.; Khan, M.R.; Singh, K.; Kumar, S.; Kabir, F. The Business of Wellness Tourism: Emerging Trends and Economic Impacts. In Human Capital Management and Competitive Advantage in Tourism; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 445–476. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).