Postfire Alterations of the Resin Secretory System in Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) Marchand (Burseraceae) †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

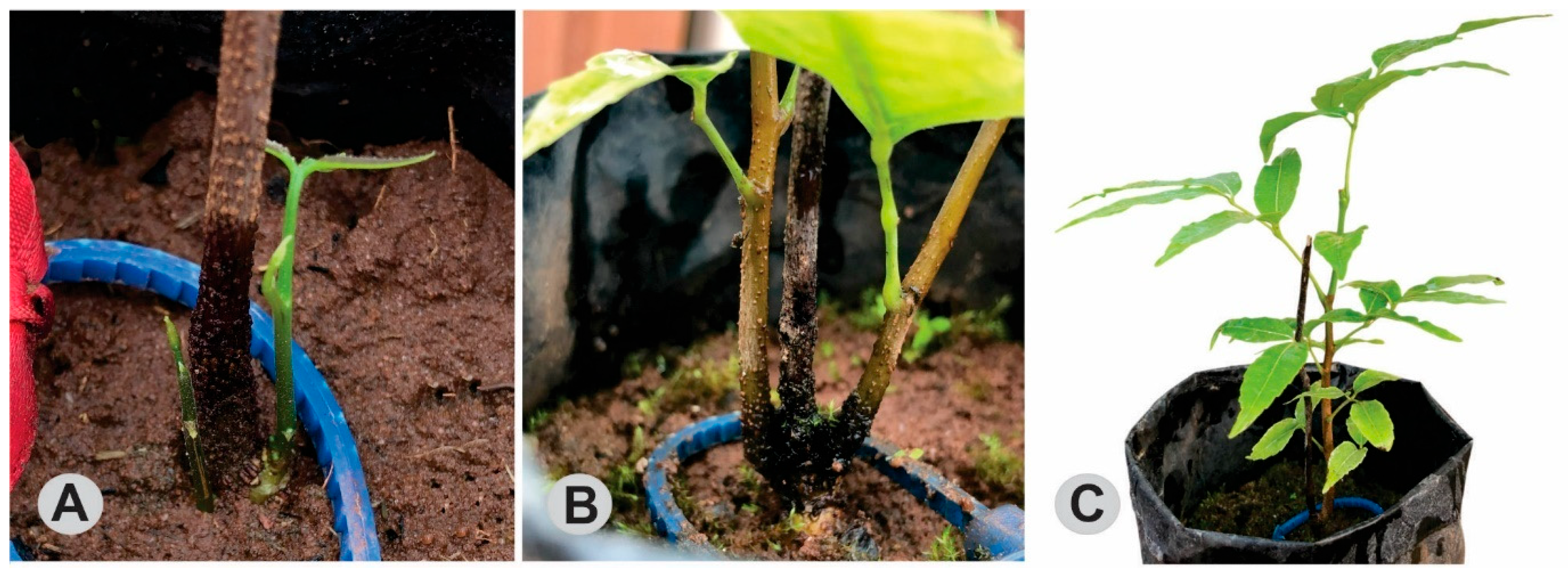

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Experimental Draw

2.3. Light Microscopy and Morphometrical Analysis

2.4. Chemical Analyses

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

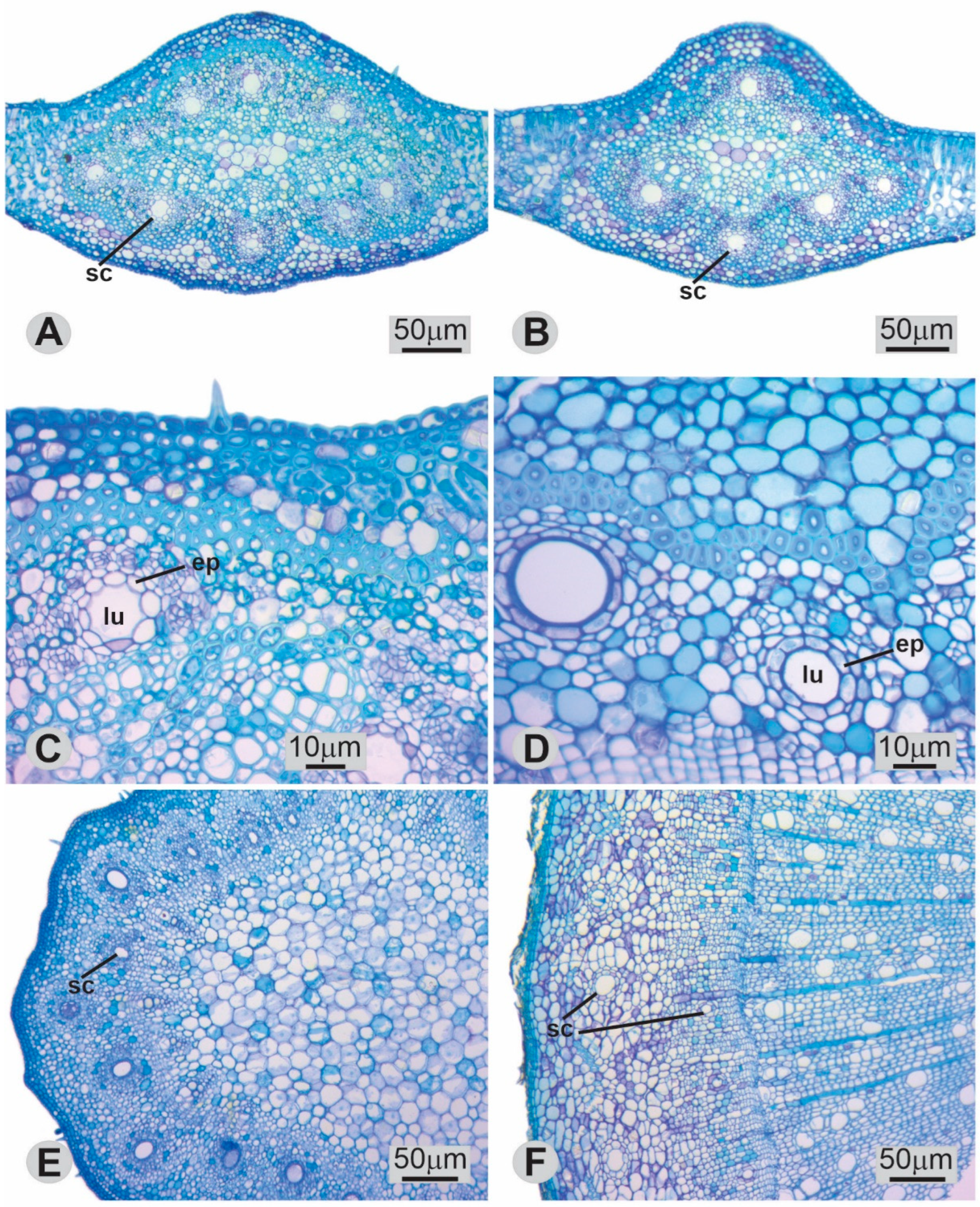

3.1. Anatomy and Morphometry of Secretory Canals

3.2. Chemical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Furley, P.A. The nature and diversity of neotropical savanna vegetation with particular reference to the Brazilian cerrados. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 1999, 8, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Mittermeier, C.G.; Da Fonseca, G.A.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, L.M. Fire in the ecology of the Brazilian cerrado. In Fire in the Tropical Biota: Ecosystem Processes and Global Challenges; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990; pp. 82–105. [Google Scholar]

- Arruda, F.V.d.; Sousa, D.G.d.; Teresa, F.B.; Prado, V.H.M.d.; Cunha, H.F.d.; Izzo, T.J. Trends and gaps of the scientific literature about the effects of fire on Brazilian Cerrado. Biota Neotrop. 2018, 18, e20170426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.F.; Grether, R.; de Queiroz, L.P.; Skema, C.; Pennington, R.T.; Hughes, C.E. Recent assembly of the Cerrado, a neotropical plant diversity hotspot, by in situ evolution of adaptations to fire. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 20359–20364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzini, C.; Heringer, E. Estudo sobre os sistemas subterrâneos difusos de plantas campestres. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 1966, 38, 85–112. [Google Scholar]

- Durigan, G. Zero-fire: Not possible nor desirable in the Cerrado of Brazil. Flora 2020, 268, 151612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, H.S.; Sato, M.N.; Neto, W.N.; Aires, F.S. Fires in the Cerrado, the Brazilian savanna. In Tropical Fire Ecology: Climate Change, Land Use, and Ecosystem Dynamics; Cochrane, M.A., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 427–450. [Google Scholar]

- Dantas, D.; Souza, M.J.; Vieira, A.; Oliveira, M.; Pereira, I.; Machado, E.; Souza, C.M.; Rocha, W. Soil influences on tree species distribution in a rupestrian cerrado area. FLORAM 2018, 25, e20170605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Moraes, H.; Cordeiro, I.; Figueiredo, N. Flora and floristic affinities of the Cerrados of Maranhão State, Brazil. Edinb. J. Bot. 2019, 76, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calixto Junior, J.T.; de Moura, J.C.; Lisboa, M.A.N.; Cruz, G.V.; Gonçalves, B.L.M.; Barreto, E.d.S.; Barros, L.M.; Drumond, M.A.; Mendonça, A.C.A.M.; Rocha, L.S.G. Phytosociology, diversity and floristic similarity of a Cerrado fragment on Southern Ceará state, Brazilian Semiarid. Sci. For. 2021, 49, e3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, G.O.; da Silva, R.C.; Souza, F.B.; Aguiar, B.A.C.; Lopes, V.C.; de Souza, P.B. Dynamics of a woody community in a Cerrado sensu stricto area in space and time. Floresta 2022, 52, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langenheim, J.H. Plant Resins: Chemistry, Evolution, Ecology, and Ethnobotany; Timber Press: Portland, OR, USA; Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, D.; Harley, M.; Martínez-Habibe, M.; Weeks, A. Burseraceae. In Flowering Plants. Eudicots; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 76–104. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, D.C.; Perdiz, R.O.; Fine, P.V.; Damasco, G.; Martinez-Habibe, M.C.; Calvillo-Canadell, L. A review of Neotropical Burseraceae. Braz. J. Bot. 2022, 45, 103–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cândido, J.; Lima, D.; Teixeira, P.R.; Souza, P. Florística do estrato arbustivo-arbóreo de uma área de Cerrado sensu stricto, Gurupi, Tocantins. Encicl. Biosf. 2016, 13, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solórzano, A.; Pinto, J.R.R.; Felfili, J.M.; Hay, J.D.V. Perfil florístico e estrutural do componente lenhoso em seis áreas de cerradão ao longo do bioma Cerrado. Acta Bot. Bras. 2012, 26, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maia, R.M.; Barbosa, P.R.; Cruz, F.G.; Roque, N.F.; Fascio, M. Triterpenos da resina de Protium heptaphyllum March (B0urseraceae): Caracterização em misturas binárias. Quim. Nova 2000, 23, 623–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, P.N.; Pessoa, O.D.L.; Trevisan, M.T.S.; Lemos, T.L.G. Metabólitos secundários de Protium heptaphyllum March. Quim. Nova 2002, 25, 1078–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, D.D.; Sartori, R.A.; Lemos, T.L.G.; Machado, L.L.; Souza, J.S.N.d.; Monte, F.J.Q. Chemical composition of the essential oils from two subspecies of Protium heptaphyllum. Acta Amazon. 2010, 40, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, M.P. Dicionário das plantas úteis do Brasil e das exóticas cultivadas: HL; Ministério da Agricultura, Instituto Brasileiro de Desenvolvimento Florestal: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1984; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, F.A.; Vieira-Júnior, G.M.; Chaves, M.H.; Almeida, F.R.; Florêncio, M.G.; Lima, R.C., Jr.; Silva, R.M.; Santos, F.A.; Rao, V.S. Gastroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of resin from Protium heptaphyllum in mice and rats. Pharmacol. Res. 2004, 49, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, P.; Lemos, T.; Santos, H. Atividade antimicrobiana e antioxidante do óleo essencial de Protium heptaphyllum. In Proceedings of the 46º Congresso Brasileiro de Química; Resumos; ABQ: Salvador, Brazil, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, V.S.; Maia, J.L.; Oliveira, F.A.; Lemos, T.L.; Chaves, M.H.; Santos, F.A. Composition and antinociceptive activity of the essential oil from Protium heptaphyllum resin. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2007, 2, 1199–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.A.; Frota, J.T.; Arruda, B.R.; de Melo, T.S.; da Silva, A.A.d.C.A.; Brito, G.A.d.C.; Chaves, M.H.; Rao, V.S. Antihyperglycemic and hypolipidemic effects of α, β-amyrin, a triterpenoid mixture from Protium heptaphyllum in mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2012, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra, J.X.; Venable, D.; Evans, P.; Bowers, W. Interactions between chemical and mechanical defenses in the plant genus Bursera and their implications for herbivores. Am. Zool. 2001, 41, 865–876. [Google Scholar]

- Palermo, F.H.; Rodrigues, M.I.d.A.; de Nicolai, J.; Machado, S.R.; Rodrigues, T.M. Resin secretory canals in Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) Marchand. (Burseraceae): A tridimensional branched and anastomosed system. Protoplasma 2018, 255, 899–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, F.H.; de Nicolai, J.; Seixas, D.P.; de Melo Silva, S.C.; Rodrigues, T.M. Distribuição, morfologia e histoquímica do sistema secretor em raízes de Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) Marchand (Burseraceae). Holos Environ. 2017, 17, 37–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.; Sampson, D.; Ceulemans, R. The effect of crown position and tree age on resin-canal density in Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) needles. Can. J. Bot. 2001, 79, 1257–1261. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, T.; Buarque, P.; Coneglian, A.; Reis, D. Light and temperature induce variations in the density and ultrastructure of the secretory spaces in the diesel-tree (Copaifera langsdorffii Desf.-Leguminosae). Trees 2014, 28, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.I.d.A.; Santos, E.M.G.; Nicolai, J.d.; Rodrigues, T.M. Leaf traits and herbivory in a resin-producing plant species growing in floodable and non-floodable areas of the pre-Amazonian white-sand forest. Rodriguésia 2024, 75, e01382023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissi, M.N.; Baeza, M.J.; Gorgone-Barbosa, E.; Zupo, T.; Fidelis, A. Does season affect fire behaviour in the Cerrado? Int. J. Wildland Fire 2017, 26, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whelan, R.J. The Ecology of Fire; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Johansen, D. Plant Micro Technique, 1st ed.; MC Graw Hill Co. Inc.: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1940. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, W.S. Simple method for differential staining of paraffin embedded plant material using toluidine blue O. Stain Technol. 1973, 48, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, X.; Zas, R.; Solla, A.; Sampedro, L. Differentiation of persistent anatomical defensive structures is costly and determined by nutrient availability and genetic growth-defense constraints. Tree Physiol. 2015, 35, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hood, S.; Sala, A.; Heyerdahl, E.K.; Boutin, M. Low-severity fire increases tree defense against bark beetle attacks. Ecology 2015, 96, 1846–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, A.W.; Zeibig-Kichas, N.E.; Kane, J.M.; Varner, J.M. Contingent resistance in longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) growth and defense 10 years following smoldering fires. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 364, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bär, A.; Michaletz, S.T.; Mayr, S. Fire effects on tree physiology. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1728–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clarke, P.J.; Lawes, M.J.; Murphy, B.P.; Russell-Smith, J.; Nano, C.E.; Bradstock, R.; Enright, N.J.; Fontaine, J.B.; Gosper, C.R.; Radford, I. A synthesis of postfire recovery traits of woody plants in Australian ecosystems. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 534, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulik, M.; Jura-Morawiec, J. An arrangement of secretory cells involved in the formation and storage of resin in tracheid-based secondary xylem of arborescent plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1268643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, S.A.B.; Hunter, W.L.; Godard, K.-A.; Wang, S.X.; Martin, D.M.; Bohlmann, J.; Plant, A.L. Insect attack and wounding induce traumatic resin duct development and gene expression of (—)-pinene synthase in Sitka spruce. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, A.; Gershenzon, J. Cloning and characterization of two different types of geranyl diphosphate synthases from Norway spruce (Picea abies). Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partelli-Feltrin, R.; Smith, A.M.; Adams, H.D.; Thompson, R.A.; Kolden, C.A.; Yedinak, K.M.; Johnson, D.M. Death from hunger or thirst? Phloem death, rather than xylem hydraulic failure, as a driver of fire-induced conifer mortality. New Phytol. 2023, 237, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrarese, L.; Trainotti, L.; Moretto, P.; de Laureto, P.P.; Rascio, N.; Casadoro, G. Differential ethylene-inducible expression of cellulase in pepper plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 1995, 29, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeles, F.B.; Morgan, P.W.; Saltveit, M.E., Jr. Ethylene in Plant Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Achard, P.; Baghour, M.; Chapple, A.; Hedden, P.; Van Der Straeten, D.; Genschik, P.; Moritz, T.; Harberd, N.P. The plant stress hormone ethylene controls floral transition via DELLA-dependent regulation of floral meristem-identity genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 6484–6489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, A.; Martín, J.A.; López, R.; Mutke, S.; Pinillos, F.; Gil, L. Influence of climate variables on resin yield and secretory structures in tapped Pinus pinaster Ait. in central Spain. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2015, 202, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, P.J.; Lawes, M.; Midgley, J.J.; Lamont, B.; Ojeda, F.; Burrows, G.; Enright, N.; Knox, K. Resprouting as a key functional trait: How buds, protection and resources drive persistence after fire. New Phytol. 2013, 197, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breece, C.; Kolb, T.; Dickson, B.; McMillin, J.; Clancy, K. Prescribed fire effects on bark beetle activity and tree mortality in southwestern ponderosa pine forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conedera, M.; Lucini, L.; Valese, E.; Ascoli, D.; Pezzatti, G.B. Fire resistance and vegetative recruitment ability of different deciduous trees species after low-to moderate-intensity surface fires in southern Switzerland. In Proceedings of the VI International Conference on Forest Fire Research; ADAI: Coimbra, Portugal, 2010; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Westlind, D.J.; Kelsey, R.G. Predicting post-fire attack of red turpentine or western pine beetle on ponderosa pine and its impact on mortality probability in Pacific Northwest forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 434, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asteggiano, A.; Occhipinti, A.; Capuzzo, A.; Mecarelli, E.; Aigotti, R.; Medana, C. Quali–quantitative characterization of volatile and non-volatile compounds in Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) Marchand resin by GC–MS validated method, GC–FID and HPLC–HRMS2. Molecules 2021, 26, 1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wen, K.-S.; Ruan, X.; Zhao, Y.-X.; Wei, F.; Wang, Q. Response of plant secondary metabolites to environmental factors. Molecules 2018, 23, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kong, D.; Fu, Y.; Sussman, M.R.; Wu, H. The effect of developmental and environmental factors on secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, C. Chemistry and biology of vitamin E. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2005, 49, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munné-Bosch, S. The role of α-tocopherol in plant stress tolerance. J. Plant Physiol. 2005, 162, 743–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Bao, Y. Vitamin E synthesis and response in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 994058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Nahar, K.; Fujita, M. Role of tocopherol (vitamin E) in plants: Abiotic stress tolerance and beyond. In Emerging Technologies and Management of Crop Stress Tolerance; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 267–289. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto, T.; Abe, H.; Mizukubo, T.; Seo, S. Phytol, a constituent of chlorophyll, induces root-knot nematode resistance in Arabidopsis via the ethylene signaling pathway. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2021, 34, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekeberg, D.; Jablonska, A.M.; Ogner, G. Phytol as a possible indicator of ozone stress by Picea abies. Environ. Pollut. 1995, 89, 55–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Morphometric Characteristics | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|

| Control | Fire | |

| Number of secretory canals | 8 (7–9) A | 7 (6–8) B |

| Lumen area of secretory canals (µm2) | 104 (85.2–121) A | 103 (82.8–131) A |

| Total lumen area of the secretory canals—CA (µm2) | 808 (653–967) A | 742 (534–907) B |

| Midrib area—MA (µm2) | 53,576 (43,072–57,898) A | 37,510 (31,284–42,227) B |

| Relation CA/MA (%) | 1.57 (1.31–1.76) B | 1.98 (1.56–2.36) A |

| Stem Portion | Morphometric Characteristics | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Fire | ||

| Primary phloem in young stem | Density of secretory canals (in 0.2 mm2) | 6 (5–7) B | 7 (6–8) A |

| Lumen area of the secretory canals (µm2) | 143 (106–178) A | 150 (108–212) A | |

| Total lumen area of the secretory canals (µm2) | 788 (637–1062) B | 1028 (797–1345) A | |

| Secondary phloem in basal stem portion | Density of secretory canals (in 0.2 mm2) | 7 (5.75–7) A | 6 (4–7) B |

| Lumen area of the secretory canals (µm2) | 177 (158–204) B | 238 (173–286) A | |

| Total lumen area of the secretory canals (µm2) | 1240 (920–1420) A | 1216 (990–1601) A | |

| Compound | Rt (min) | MM (g/mol) | Relative Percentage Per Treatment | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Fire | ||||

| MM = 220 | 21.55 | 220 | 0.85 ± 0.03 A | 0.71 ± 0.08 A | 0.2880 |

| MM = 278a | 25.98 | 278 | 1.84 ± 0.14 B | 3.43 ± 0.38 A | 0.0252 |

| MM = 278 b | 26.86 | 278 | 0.27 ± 0.27 B | 1.07 ± 0.12 A | 0.0163 |

| Phytol | 31.30 | 296 | 1.04 ± 0.06 B | 1.78 ± 0.17 A | 0.0205 |

| MM = 284 | 34.50 | 284 | 1.25 ± 0.68 A | 1.05 ± 0.41 A | 0.7920 |

| Esqualene | 42.61 | 410 | 3.77 ± 0.29 A | 3.43 ± 0.26 A | 0.4470 |

| γ-tocopherol | 45.86 | 416 | 1.29 ± 0.10 A | 1.67 ± 0.33 A | 0.4720 |

| Vitamin E | 47.27 | 430 | 34.19 ± 0.39 A | 20.79 ± 1.67 B | 0.0009 |

| Sitosterol | 51.20 | 414 | 19.71 ± 1.33 A | 15.40 ± 1.22 A | 0.0661 |

| β-amyrin | 51.97 | 426 | 3.25 ± 0.54 A | 2.87 ± 0.27 A | 0.4860 |

| α-amyrin | 53.21 | 426 | 7.99 ± 0.60 A | 8.49 ± 0.81 A | 0.7020 |

| Total identified (%) | - | - | 71.25 | 54.41 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pereira, T.C.; Martins, A.R.; de Oliveira, A.d.S.S.; Sartoratto, A.; Rodrigues, T.M. Postfire Alterations of the Resin Secretory System in Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) Marchand (Burseraceae). Forests 2025, 16, 923. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16060923

Pereira TC, Martins AR, de Oliveira AdSS, Sartoratto A, Rodrigues TM. Postfire Alterations of the Resin Secretory System in Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) Marchand (Burseraceae). Forests. 2025; 16(6):923. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16060923

Chicago/Turabian StylePereira, Thalissa Cagnin, Aline Redondo Martins, Adriana da Silva Santos de Oliveira, Adilson Sartoratto, and Tatiane Maria Rodrigues. 2025. "Postfire Alterations of the Resin Secretory System in Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) Marchand (Burseraceae)" Forests 16, no. 6: 923. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16060923

APA StylePereira, T. C., Martins, A. R., de Oliveira, A. d. S. S., Sartoratto, A., & Rodrigues, T. M. (2025). Postfire Alterations of the Resin Secretory System in Protium heptaphyllum (Aubl.) Marchand (Burseraceae). Forests, 16(6), 923. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16060923