Abstract

Forest areas have recently become increasingly popular for physical activity in society, especially among niche sports enthusiasts. We analysed the attitude of the specific social group of cross-country skiers in Poland to pay for recreation in forest areas using their Willingness-To-Pay (WTP) and Willingness-To-Accept (WTA) declarations, which was endorsed by classification and regression tree (CART) analysis. In January–March 2023, we surveyed 50 (in a pilot study) and 255 (in the main survey) cross-country skiers, of whom 117 declared both their WTP and WTA amounts. The investigated explanatory variables included gender, age, education, residency, employment in the forestry sector, and respondents’ income or engagement in skiing. The average WTP and WTA values equalled PLN 68.6 ± 46.4 and PLN 81.3 ± 59.0/person, respectively. Despite apparent differences in the distribution of the declared WTP and WTA amounts, their medians differed only insignificantly. We found a significant correlation only between the WTP value and respondents’ income per capita, and between WTP and WTA. The CART models showed that WTP and WTA levels depended primarily on the frequency of skiing, with higher values declared by less frequent visitors. At the current respondent income level, the expenses for skiing were related the most to the respondents’ age and the frequency of skiing. In the case of increased income, they were related mostly to the respondents’ age and place of residence. The research provides practical information for forest managers in the field of recreational access to forests for people who spend their time actively in forests.

1. Introduction

Recently, there has been a growing interest in relaxing and recreation in forests. This process is driven by increased resources (in terms of both income and leisure time), environmental and nature awareness, and growing concern about physical and mental health [1,2,3,4,5]. The regenerative properties of woodlands have long been known widely [6,7,8]. The increased level of physical activity in forests is also related to their easy access to the public [4,9]. The most common forms include walking, trekking, jogging, running or cycling. They are realised both in commercial and urban forests [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Other leisure activities such as orienteering [19], Nordic walking and birdwatching [20,21] or cross-country skiing [22,23] are also gaining popularity. Moreover, recreation in forest areas sensitises people to the aesthetics and beauty of the landscape [24].

In Scandinavian countries or Canada, cross-country skiing has a well-established, long-standing tradition and became fashionable as a form of recreation as early as the mid-1880s [25]. In recent years, this form of physical activity has also gained more and more popularity in Poland [26]. In 2008, there were 1.2 thousand cross-country skiers in sports clubs in Poland, and in 2023, their number had already tripled, reaching more than 3.6 thousand [27,28]. Cross-country skiing is a sport that can be practised by anyone, as the cost of equipment is not high. The number and length of cross-country ski trails, many of which are located in forest areas, are also increasing. In addition to ski trails, traditional walking or cycling trails can be used for skiers, too [29]. The length of the marked or established ski trails in Poland increased from 431 km in 2015 to 911 km in 2022 [28]. The existing linear infrastructure in forests (roads, divisional lines) favours this sport [30]. Most cross-country ski trails are located in southern Poland [31], but the popularity of the sport has caused them to appear also in other regions of the country [32,33]. Lowland areas that are not suitable for downhill skiing are also gaining in importance, e.g., the Barycz Valley [34], because the only necessary condition for cross-country skiing is the appropriate thickness and duration of snow cover and a temperature below 0 °C.

Social preferences for recreational use of forests are an increasingly important issue, especially in the light of conducting multifunctional forest management, which also takes into account the fulfilment of many social needs [16,18,35]. Recognition of the recreational needs and demands in society will allow the proper use of the recreational potential of forests and the adaptation of the recreational infrastructure for the implementation of many activities of different stakeholders. Most studies on the recreational use of forest areas concern spring, summer and autumn months. For example, people running in forest areas in Poland and the Czech Republic indicated mainly summer and spring as the time of their activity [15,35]. This trend concerns many physical activities carried out in forest areas. The research on social preferences about winter sports is missing. This situation results from more challenging research conditions and people’s lower outdoor activity in winter than in summer [33]. The literature on the subject also lacks reports on the willingness to pay for forest recreation declared by those actively spending their free time during winter [17,35,36,37].

This study attempted to evaluate the value of recreation among cross-country skiers using the Willingness-To-Pay (WTP) and Willingness-To-Accept (WTA) methods. In this context, the measure of recreational value is the benefit derived from forest recreation. Although the valuation of forest recreation has been conducted for the whole of Poland and for the most extensive forest complexes [38], its results do not consider the benefits for specific groups of forest recreation users. Our study aimed to fill this research gap, and its results will also provide insights into the socio-sport functions of forests.

Nowadays, forest management implies combining multifunctionality, biodiversity and changing social preferences over time, for example, if only a community forest designation is concerned. There is also a lot of social pressure to conduct forest management. For recreation, users choose forests of different forms of ownership; often, these are areas around cities. Our study can be a valuable guide for managers of these areas regarding their accessibility for recreation, taking into account social preferences.

This study aimed to analyse the social preferences of a group of Polish cross-country skiers in terms of their willingness to pay for recreation in forest areas, depending on the sociological characteristics of the respondents and the frequency of visits.

Due to the exploratory nature of the conducted research, the following research questions were formulated: (i) “Which sociological features significantly determine the value of WTP for forest recreation in winter in the group of cross-country skiers in Poland?”, (ii) “Which sociological features significantly determine the value of WTA in this group of users?” and (iii) “Is there a relationship between the values of WTP and WTA?”

2. Materials and Methods

To determine the level of funding for recreation in the forests, we applied two widely used variants of the contingent evaluation method, namely Willingness-To-Pay and Willingness-To-Accept declarations [39]. The previous method involves creating a hypothetical scenario in which respondents indicate their willingness (or lack thereof) to protect an area of natural/recreational value. In different question formats, they declare specific amounts (or ranges of amounts) of money for the maintenance of the asset in question in a hypothetical threatened situation. In the latter variant, respondents declare their willingness to accept compensation for losing the opportunity to use the good/service in question at their previous frequency.

In January 2023, we carried out a pilot study that involved cross-country skiers realising their hobby in forested areas. We questioned a group of 50 people during local cross-country skiing competitions. This part of the research allowed for the refinement and adjustment of the questionnaire. Its construction was based on similar studies about sport or touristic activities in forests, which ensured the content validity of the performed research.

The main part of the survey was carried out from February to March 2023 on a group of 255 cross-country skiers who participated in the competitions organised in forest areas or in their immediate vicinity. Every 10th participant in the competition was asked to complete the questionnaire after consenting to participate in the study. This approach yielded 171 responses. Additionally, we used a snowball sampling method to gather some more surveys online using the Survio tool. This method of data collection provided a further 84 responses. The survey included an age criterion (18 years and older), allowing for an analysis focused solely on adults. The most important criterion of respondent selection was cross-country skiing in the forested areas. The process began with identifying an initial participant who met the criteria and was then asked to refer additional individuals who met the study’s assumptions. After completing the survey, each subsequent respondent forwarded the questionnaire link to the next ones. The average time to complete the survey was approximately 5–7 min.

The questionnaire was written in Polish (for the English version, see Supplementary Material S1) and consisted of two parts. The first one included demographic variables such as gender, age, place of residence, education and the income of the respondents. In the other part of the questionnaire, the pertinent questions asked the skiers to indicate the amount of WTP (funding the possibility to practise cross-country skiing in forests) and WTA (amount of compensation for giving up the sport at the current frequency). In the case of answer refusals, respondents were asked to give the reasons. Respondents were also asked to specify the proportion of their monthly income allocated to skiing expenses at their current income level and in the case that their income increased satisfactorily. An open-top quota payment card format was used to determine WTP and WTA amounts. Additionally, respondents indicated how often they practise cross-country skiing in forest areas during the winter season.

Out of all collected surveys, we found both WTA and WTP declarations only in the case of 117 (38%). None of these declarations was recorded in the case of 51 (17%) surveys. As the distributions of the principal descriptive socio-economical features in the whole sample (305 responses) and in the subsample with simultaneous WTA and WTP records (117) were quite similar, we considered that the collected material describes the skiers appropriately and constitutes a sufficient sample size for the intended analyses.

On the basis of the declared values of WTP and WTA, we calculated the WTA/WTP ratio. Furthermore, analysing the relation between WTA and WTP, we distinguished three classes of this index. They describe the situation when the respondent declares their willingness to pay for a given economic good that is lower than (WTA/WTP > 1), higher than (WTA/WTP < 1) or equal to (WTA/WTP = 1) the amount they declared they would accept in the case of skipping that good.

As the distribution of the investigated measures significantly departed from the normal one (Shapiro–Wilk test; WTP: W = 0.87, p < 0.001; WTA: W 0.87, p < 0.001; WTA/WTP: W = 0.71, p < 0.001), to assess the significance of the observed differences, we used the nonparametric tests (Mann–Whitney or Kruskal–Wallis), depending on the number of levels of the analysed factor. The relationships with quantitative attributes were estimated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. We used contingency tables to examine whether the investigated factors influence the type of the WTA and WTP relationship (classes of WTA/WTP index). The chi-squared test was applied, and Cramer’s V and Pearson’s C contingency coefficients were calculated to assess the level of potential association. All calculations were made using PAST 4.17 software [40]. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Additionally, to analyse the relationship between the declared values of WTP and WTA and the characteristics of the respondents, the Classification and Regression Tree (CART) method was used. This approach allowed the identification of key characteristics of the respondents that significantly affect their stability. CART is a nonparametric data analysis technique based on decision trees that recursively divide the data into smaller, homogeneous subsets in order to predict the value of the dependent variable. The CART model results were visualized using tree plots. This method constructs a model that solves regression problems where the dependent variable is a quantitative feature and classification models where the dependent variable is a qualitative feature [41,42]. The analysis was performed in R 4.4.2 [43] using the rpart package.

3. Results

The respondents who declared WTA and WTP amounts (N = 117) were characterised by a slight gender imbalance (44.4% females vs. 55.6% males). The majority of the answers were obtained from people aged 25–34 and 45–54 years (36.8 and 28.2%, respectively). The youngsters (≤24 years old) constituted 12.0% of the analysed population, while the share of the elderly people (≥65 years old) equalled only 3.4%. The vast majority of the respondents had higher (64.1%) or secondary (33.3%) education, while people with primary education constituted only 2.6% of the respondents. Regarding the occupation, 19.7% of the responses were given by employers from the forestry sector. People who participated in the survey mostly lived in rural areas (46.2% of the respondents). The fraction of urban residents distributes more or less equally among the analysed classes (16.2%–19.7%).

In terms of their economic status, the respondents showed quite uneven distribution among the distinguished classes of income. The most numerous fraction (47.0%) earns PLN 5000–10,000 monthly. The richest (PLN > 10,000 of monthly income) and the poorest people (PLN ≤ 2000 of monthly income) constituted a similar part of the respondents (6.8 and 6.0%, respectively). As much as 13.7% of the surveyed people use their income only for their own. The most numerous situation included three or four persons living on that money (53.8% responses). In 12% of cases, the declared income served five or more people. Per capita, declared income most often ranged between PLN 1000 and 2000 as well as PLN 2000–3000 (34.2 and 36.8% of the responses, respectively). More than PLN 4000/person/month is available for only 4.3% of respondents, while 13.7% live on less than PLN 1000/person/month.

Almost half of the respondents who declared WTP and WTA values go cross-country skiing quite often (more than once a week or more than once a month, 27 and 24%, respectively). The most active skiers, who perform their hobby every day, constituted 11% of the respondents. Less frequent activities (answers: from time to time, once every several weeks) characterised the remaining 38% of skiers. On average, the investigated skiers spend PLN 1112 for their hobby, but the values range widely from PLN 0 up to PLN 10,000. The distribution of declared expenses is highly asymmetric (skewness = 3.21).

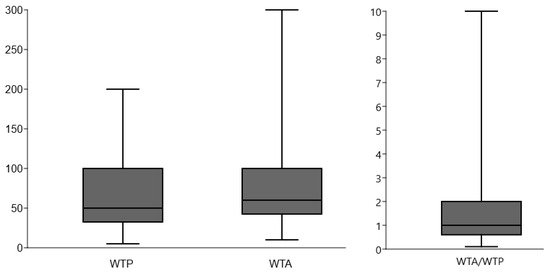

On average, the surveyed cross-country skiers declared the willingness to pay PLN 68.6 ± 46.4 for the ability to perform their hobby. The recorded values ranged from PLN 5 to 200, with the median at PLN 50 (Figure 1). They are characterised by high variability (coefficient of variance (CV) = 67.7%). The distribution of the WTP values was slightly positively skewed (skewness = 1.03). In turn, the mean amount of money the skiers were willing to accept to skip skiing (WTA) was much higher than the average WTP and equalled PLN 81.3 ± 59.0. The declared values varied from PLN 10 to 200, with a median of PLN 60 (Figure 1). The variability of the records was high (72.6%), and their distribution was positively skewed (skewness = 1.21).

Figure 1.

Distribution of WTP (PLN), WTA (PLN) and WTA/WTP index values.

Despite apparent differences in the distribution of the declared amounts (Figure 1), the median values of WTP and WTA for the analysed group did not differ significantly (Z = 1.65, p = 0.098). In turn, the declared WTA and WTP values were significantly correlated with each other (r = 0.213, p = 0.021). However, this relationship was relatively weak and unambiguous (Figure 2a).

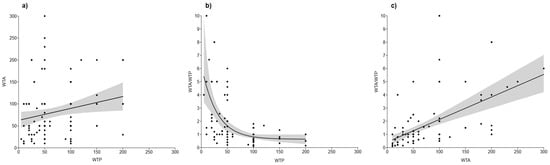

Figure 2.

Relationships among WTA and WTP (a), WTA/WTP and WTP (b), and WTA/WTP and WTA (c). Grey areas indicate 95% confidence intervals.

WTA/WTP ratio values ranged from 0.1 to 10, equalling 1.81 on average ± 1.98. The median value of this index amounted to 1.0 (Figure 1). The distribution of the index values was highly positively skewed (skewness = 2.23), and the variability of the records was very high (CV = 109%). In 44.4% of cases, ratio values exceeded 1 (i.e., situation when WTA > WTP), while 33.3% of its values were lower than 1 (WTA < WTP). Equal amounts of both WTA and WTP indexes were declared by 22.2% of the respondents.

WTA/WTP significantly depended on both WTA and WTP values (r = 0.511, p < 0.001 and r = −0. 472, p < 0.001, respectively). However, the character of the relationship with the particular component of the index was the opposite (Figure 2b,c).

None of the analysed qualitative factors significantly influenced the WTP values. Neither gender (p = 0.766), education level (p = 0.125), residency (p = 0.201), region of origin (p = 0.732) nor employment in forestry (p = 0.373) turned out to be that important in distinguishing significantly different groups. Additionally, we found no significant relationship between WTP values and respondents’ age (r = 0.083, p = 0.375) and income (r = 0.027, p = 0.771). However, in the case of income per capita, the relationship turned out to be significant (r = 0.184, p = 0.047).

A similar situation was observed for WTA. Both qualitative and quantitative factors had no effect on this feature. Neither gender (p = 0.240), education level (p = 0.892), residency (p = 0.508), region of origin (p = 0.067) nor employment in forestry (p = 0.253) turned out to be an essential factor. No significant relationship was found between WTA and respondents’ age (r = 0.146, p = 0.116), income (r = 0.017, p = 0.858) or income per capita (r = −0.045, p = 0.627).

In terms of the WTA/WTP index, none of the analysed quantitative or qualitative factors caused any significant differences in the distribution of the respondents to the individual classes of the index (Table 1). Values of the contingency coefficients were also very low.

Table 1.

Influence of the analysed factors on the WTA/WTP index class.

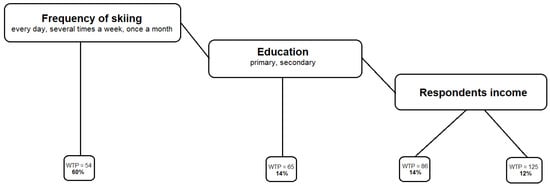

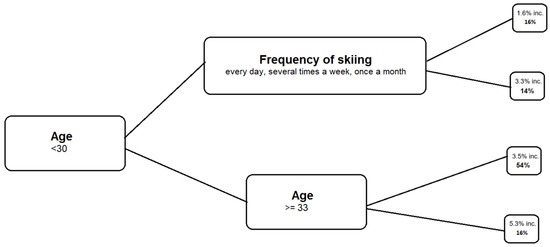

The CART analysis revealed that variables influencing WTP and its value were primarily the frequency of cross-country skiing, followed by sociological characteristics such as education and income of respondents (Figure 3). Those who ski more than once a month are willing to pay an average of PLN 54, while others would pay an average of PLN 91. The latter group is further divided by education level. Respondents with primary or secondary education would pay an average of PLN 65. The remaining individuals are also divided by their income.

Figure 3.

Impact of the analysed variables on WTP.

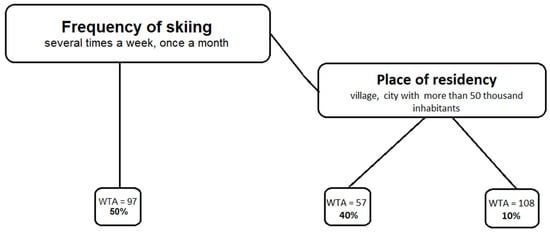

In the case of the WTA value, the frequency of visits also had the greatest impact on the declared amount of compensation (Figure 4). Respondents who answered “a few times a week” or “once a month” are willing to accept PLN 97 on average. People living in rural areas or in cities with more than 50 thousand inhabitants could accept PLN 57 on average, while another 10% would accept PLN 108.

Figure 4.

Impact of the analysed variables on WTA.

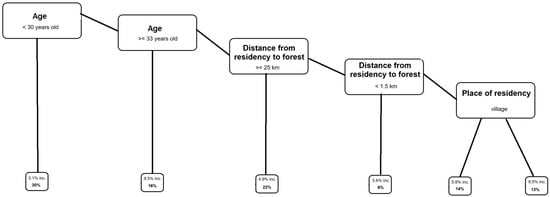

In the current income situation, the greatest impact on the expenditure for cross-country skiing can be attributed to age, followed by frequency of skiing (Figure 5). More active (higher frequency) or older (≥33 years old) skiers pay less. Had income increased, it is respondents’ age followed by distance from their place of residence to the forest that affect the amount of money spent for the investigated form of activity. However, the pattern behind that is rather unclear (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Impact of the analysed variables on the amount spent on skiing according to the current income (% inc.—declared fraction of income).

Figure 6.

Impact of the analysed variables on the amount spent on skiing according to the increased income (% inc.—declared fraction of income).

4. Discussion

The value of the natural environment estimated using WTP or WTA measures often takes different monetary values, which is widely discussed in the literature [44,45,46]. As Zawilinska [47] presents, both methods should give similar (or slightly different) assessment results. However, the difference between WTP and WTA results from the demand of respondents, which describes highly valued environmental goods and services when there are few substitutes [48,49]. This disproportion referring to identical changes in goods and services indicates how important the aspect of selecting appropriate welfare measures is in order to properly assess the economics of these changes, which is particularly important in the area of goods without market prices [50]. The substitution effect and the income effect were indicated as an explanation for the observed disproportions in WTA and WTP, with expected utility [48]. In turn, the studies of Horowitz and McConnell [51] or Sudgen [52] indicate that substitution and income effects are not limited only to the observed differences. The difference between WTP and WTA may also be caused by the so-called loss aversion [53], which often results in an overestimation of WTA compared with WTP [54,55]. Therefore, WTA can be considered a measure of the refusal to provide an environmental good at present, although due to the difficulty of designing effective questions using this method, it is recommended to use the WTP format [56]. The literature also contains studies that argue that the difference between WTP and WTA results from the endowment effect and loss aversion. Based on the Kahneman and Tversky perspective theory known in the psychology of consumer behaviour, people have a higher tendency to avoid losses than to make gains, which leads to a higher WTA than WTP [53]. In the case of the present study, the declared values of WTP and WTA differed slightly. Respondents indicated that they would expect higher compensation for depriving themselves of the opportunity to practice cross-country skiing in the forest (an average of PLN 81.3/person) than they would be able to offer for the protection and maintenance of the forest (an average of PLN 68.8/person). The results indicating a situation in which cross-country skiers declare their willingness to receive higher compensation for giving up access to this type of recreation than their willingness to pay for it may result from the fact that loss aversion will be stronger than the benefits of gain. They therefore base the decision on the amount of WTP and WTA in terms of gain and loss, which is the assumption of one of the behavioural theories: loss aversion and the endowment effect [53,54,55]. According to these concepts, a person analysing a given situation is guided primarily by emotional, not rational, premises. In turn, the endowment theory assumes that people assign a higher value to lost objects or goods. This situation is similar to that reported for Guiyang in China [57], in Guyana [58] or in various developing countries [46].

The findings on funding recreation among cross-country skiers in forested areas in Poland are representative of the group participating in the study. Only 38% of the respondents simultaneously declared both a willingness to pay for forest protection (WTP) and a willingness to accept compensation for the loss of skiing opportunities in the forest at their current frequency (WTA), which constitutes a limitation of our study. A low percentage of respondents declaring WTA is also observed in other studies [46]. In comparison, the number of individuals declaring WTP for forest protection or financing forests for recreational use reaches higher values, ranging from 50% to 80% [17,35,59].

A number of studies on preferences among people resting in forested areas indicate that the declared amounts of WTP and WTA depend on the sociological characteristics of the respondents [60,61,62,63]. We found a significant correlation between the amount of WTP and respondents’ income, as well as between WTA and WTP values. Many findings confirm the general trend that as the income of respondents, entire families or society increases, their declared WTP also rises [60,64,65,66,67]. Interestingly, completely different results are presented by Mandziuk et al. [68], which indicate no correlation between income levels and WTP amounts. It should be remembered, however, that the relationship between income and willingness to pay for recreation in the forest may be bidirectional. It may result not only from external conditions, e.g., the recreational accessibility of forest areas, but also internal (personal) ones. People who prefer to rest in the fresh air will spend larger amounts of money on this style of recreation. The willingness to pay for this style of recreation also results from personal reasons.

Interestingly, no correlation was revealed between sociological characteristics and WTA. In comparison, the results of the CART analysis show that WTP and WTA are the most influenced by the frequency of recreational activities among cross-country skiers.

Income, education and place of residence were also significant factors in WTP amounts. The frequency of visits is also a significant factor in other Polish studies on attributes influencing WTP among forest recreationists when their income is doubled [34,59]. This factor was also decisive in determining how much respondents spent on cross-country skiing at their current income level. On the other hand, when income was increased, the age and place of residence of the respondents was the most critical factor.

The amount of WTP in other Polish studies also depends on education: the higher the education, the higher the declared amounts for forest recreation [35]. In turn, the results of the CART analysis for recreation in Poland in protected areas indicate that the WTA level was most influenced by age and, similar to our study, the place of residence of the respondents [69], and by the place of residence of respondents [70] in the case of WTP.

There are many various motives for protecting socially relevant natural areas. Therefore, the willingness to pay depends, among other things, on the appearance of the forest [39,71,72], the quality of the forest environment [73] or the accessibility of the forest complex [36,74]. Preferences regarding society’s willingness to finance forest recreation (WTP and WTA) change over time [36]. The value of WTP and WTA also depends on a given society’s environmental and economic factors, as well as the forest policy of a particular country. A compromise is required when forest management is directed toward a specific service, such as the economic use of timber at the cost of soil erosion, wildfires, or reduced biodiversity [75], while also ensuring public access to free recreational areas that support specific activities [76]. Among the indicated attributes, we also find the presence of recreational infrastructure [36,37,77]. However, it has been reported that some respondents choose forests without appropriate infrastructure for recreation [64,78]. This trend is confirmed by research findings [37,79], which indicate that higher WTP values correlated with recreational facilities in forests. In contrast, such a relationship was not observed in other Polish studies on the recreational use of forest areas [64], where the respondents declared higher WTP for forests without recreational infrastructure. Interestingly, respondents who pointed out missing infrastructure elements, such as benches, tables, educational trails, running tracks or parking lots, reported higher WTP values.

Any recreational activity in forest areas has an impact on the environment. As noted by Smoleński [80], cross-country skiing in the context of forest environments represents a sports-related ecotourism activity. However, it does not cause adverse environmental effects, and its impact on the forest ecosystem is minimal compared with activities such as horseback riding or hiking [81]. Other winter sports such as alpine skiing or snowboarding impact the natural environment significantly more intensively [82].

The recreational provision of the forest requires forest managers to pay particular attention to protecting forest areas and ensuring visitors’ safety [83]. Compared with other sports, such as horse riding or hiking, cross-country skiing has rather no or very low impact on the vegetation cover, being the most environmentally friendly form of activity [81]. Therefore, an important aspect is the proper design of recreational trails, including those for cross-country skiing, so that they do not have a negative impact on the forest ecosystem and, in addition, lead through diverse landscapes offering a constantly changing forest appearance [24].

An undeniable limitation of the study is the period in which it was conducted, covering only a few winter months. Given the observed climate changes, including a decreasing number of days with subzero temperatures and reduced snowfall, especially in lowland areas, it is likely that this period will continue to shorten in the coming years. Despite climate change, the authors assume that due to the free access to forest areas in Poland, the relatively low costs of cross-country skiing and the increasing number of ski trails, this sport—although currently considered niche—will gain popularity in the country. Therefore, it would be beneficial to continue survey research in different regions of Poland. The current study included cross-country skiers using forest areas across the country. Expanding the research would help identify regional differences in social preferences. Future studies should also be preceded by further validation of the questionnaire.

The challenge for forest managers is the increasing social pressure and determining the method of participation in the costs of maintaining recreational infrastructure. Another difficulty is determining the possible process of enforcing fees for recreational use of the forest. It would be necessary to consider who and on what terms such payments would be collected. The research results among Polish forest managers indicate that such fees should be collected from entities deriving financial benefits from using the forest [84]. The principles according to which such fees could be established and collected should be precisely formed. The results of our research may be a clue concerning the demonstrated dependence of WTP on the level of income and the frequency of active recreation in forest areas. Therefore, fees could be differentiated depending on the occurrence of these factors. The amount of the voluntary fee could depend on the frequency of cross-country skiing during the winter season. The more often the activity, the lower the amount would be. Another proposal is to introduce time-based (different) subscriptions, taking into account the frequency of recreation, income and the number of people in the family.

5. Conclusions

The survey analysed the influence of various sociological characteristics on the attitude of cross-country skiers in Poland to pay for the possibility of performing their sport in the forests or accept financial compensation to waive it. We found that values of Willingness-To-Pay and Willingness-To-Accept measures for the analysed group of sportsmen are similar and depend on the economic status of the respondents (income) and the frequency of visits to the forest to realise their physical activity. However, it should be remembered that the motivation for higher WTP does not have to be related to the amount of income. It may result from the fact that people who prefer outdoor recreation lead a healthy lifestyle, in which economic expenditure on such activities is a priority. Interestingly, those who ski more seldom declare higher values.

The research showed a relationship between respondents’ income and their willingness to finance forests for their recreational use, which stays in line with other studies on social preferences depending on sociological characteristics. No such relationship was found between other sociological features of the respondents and WTP and WTA. The frequency of cross-country skiing in forests has the most significant influence on the amount of WTP and WTA. Almost half of the respondents declaring WTP and WTA quite often ski in the forest.

The amounts of WTP and WTA declared by the respondents differed, with a slight advantage of WTA over WTP. These results confirm other literature reports, and it seems that the motivations guiding the respondents in indicating them result from loss aversion and the endowment effect.

Recognition of the variability in and drivers of social preferences in various fields of recreational use of forests will enable forest authorities to develop the appropriate policy of making the forest available with regard to multifunctional and sustainable forest management and nature protection.

The organisation of recreation in forest areas (different forms of ownership) is currently a significant challenge in creating social, sports, forest and environmental policies combining the multi-aspect nature of forest management. It requires cooperation among managers/owners of these areas, local and self-government authorities and the athletes themselves. The research results can help develop environmental development strategies and programs supporting the creation of modern health policies combining the needs and preferences of people cross-country skiing in the forest regarding the recreational adaptation of forest complexes to their needs. They can serve as guidelines for integrated recreational planning at various levels of forest management: local, regional and national. For this purpose, research should be expanded to include new research areas.

The obtained research results introduce the possibility of determining payments for recreational use of the forest. Their amount may depend on the frequency of active recreation in forest areas and the amount of income. However, this may be difficult to implement as an obligation due to the public nature of forests in Polish conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f16030389/s1. S1 Questionnaire: Assessment of recreational use of forest areas by cross-country skiers in Poland.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.; methodology, A.M.; software, S.B. and M.S.; validation, S.B.; investigation, A.M.; resources, A.M., J.R., I.Ł. and S.P.; data curation, S.B.; visualization, A.M. and S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M., S.B., I.Ł., J.R., M.S. and S.P.; writing—review and editing, A.M., I.Ł., S.B. and S.P.; supervision, A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethics committee approval because it was a survey-based study that did not involve procedures or interventions covered by the Declaration of Helsinki. The study did not involve medical or clinical interventions. It did not involve invasive methods or procedures. It did not collect sensitive or identifiable data that could harm participants. It did not include participants who were unable to give informed consent or involve any sensitive populations. It had no significant psychological impact on participants. In accordance with our institution’s policy, survey-based research of this nature is not subject to review by an ethics committee.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable; no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to give special thanks to Stanisław and Mateusz Mandziuk, the foresters who combined their work with their passion for cross-country skiing, for their inspiration of the research topic and for their help in conducting the surveys.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hartig, T.; Mitchell, R.; De Vries, S.; Frumkin, H. Nature and Health. Ann. Rev. Pub. Health 2014, 35, 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, K.; Bentsen, P.; Grahn, P.; Mygind, L. What Is the Scientific Evidence with Regard to the Effects of Forests, Trees on Human Health and Well-being? Sante Publ. 2019, S1, 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soroka, A.; Wojciechowska-Solis, J. Oczekiwania polskiego społeczeństwa związane z działalnością rekreacyjno-turystyczną w środowisku leśnym (Expectations of the Polish society related to recreational and tourist activities in the forest environment). Sylwan 2020, 164, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E. Las i zdrowie publiczne (Forest and public health). In Leśnictwo Polski Wobec Wyzwań Polityki Unii Europejskiej. Zimowa Szkoła Leśna Przy Instytucie Badawczym Leśnictwa; Kaliszewski, A., Ed.; Instytut Badawczy Leśnictwa: Sękocin Stary, Poland, 2023; pp. 341–361. ISBN 978-83-67801-05-8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Huang, N.; Weng, Y.; Tong, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Dong, J.; Wang, M. Does Soundscape Perception Affect Health Benefits, as Mediated by Restorative Perception? Forests 2023, 14, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, N.; Korpela, K.; Lee, J.; Morikawa, T.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Park, B.-J.; Li, Q.; Tyrväinen, L.; Miyazaki, Y.; Kagawa, T. Emotional, restorative and vitalizing effects of forest and urban environments at four sites in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 7207–7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielinis, E.; Takayama, N.; Boiko, S.; Omelan, A.; Bielinis, L. The effect of winter forest bathing on psychological relaxation of young Polish adults. Urb. For. Urb. Green. 2018, 29, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théberge, D.; Flamand-Hubert, M.; Nadeau, S.; Girard, J.; Bradette, I.; Asselin, H. Forest-Based Health Practices: Social Representations of Nature and Favorable Environmental Characteristics. Forests 2024, 15, 1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, P.; Banay, R.F.; Hart, J.E.; Laden, F. A review of the health benefits of greenness. Curr. Epidem. Rep. 2015, 2, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janowsky, D.; Becker, G. Characteristics and needs of different user groups in the urban forest of Stuttgart. J. Nat. Conserv. 2003, 11, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnberger, A. Recreation use of urban forests: An inter–area comparison. Urb. For. Urb. Green. 2006, 4, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudek, T. Badanie preferencji mieszkańców województwa podkarpackiego dotyczących wypoczynku w lasach (A study on subcarpathian voivodeship inhabitants’ preferences concerning leisure time in forests). Nauk. Przyr. Techn. 2017, 11, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Janeczko, E.; Woźnicka, M.; Tomusiak, R.; Dawidziuk, A.; Kargul–Plewa, D.; Janeczko, K. Preferencje społeczne dotyczące rekreacji w lasach Mazowieckiego Parku Krajobrazowego w latach 2000 i 2012 (Social preferences regarding recreation in forests of the Mazowiecki Landscape Park in 2000 and 2012). Sylwan 2017, 161, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Fialova, J.; Tomusiak, R.; Woźnicka, M.; Janeczko, K.; Budnicka-Kosior, J.; Kwasny, Ł. Atrakcyjność imprez biegowych w lasach Polski i Czech (Attractiveness of running events in forests of Poland and Czech Republic). Sylwan 2018, 162, 610–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janeczko, E.; Fialová, J.; Tomusiak, R.; Woźnicka, M.; Procházková, P. Bieganie jako forma rekreacji w lasach Polski i Republiki Czeskiej—Zalety i wady (Running as a form of recreation in the Polish and Czech forests—Advantages and disadvantages). Sylwan 2019, 163, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandziuk, A.; Kikulski, J.; Parzych, S. Społeczne potrzeby i preferencje w zakresie wypoczynku na terenach chronionych na przykładzie rezerwatu przyrody ”Nad Tanwią” (Social needs and preferences in the field of leisure in protected areas—‘Nad Tanwią’ nature reserve case study). Sylwan 2019, 163, 1016–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornal-Pieniak, B.; Mandziuk, A.; Kiraga, M. Wybrane Aspekty Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Zielonych Przestrzeni Miejskich (Selected Aspects of Sustainable Development of Urban Green Spaces), 1st ed.; Wydawnictwo SGGW: Warszawa, Poland, 2023; p. 74. ISBN 978-83-8237-093-5. [Google Scholar]

- Jakstis, K.; Dubovik, M.; Laikari, A.; Mustajärvi, K.; Wendling, L.; Fischer, L.K. Informing the design of urban green and blue spaces through an understanding of Europeans’ usage and preferences. People Nat. 2023, 5, 162–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurek-Kusiak, A.; Soroka, A. Motywy i bariery uprawiania orientacji sportowej w środowisku leśnym (Motives and barriers to practice orienteering in the forest environment). Sylwan 2021, 165, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skłodowski, J.; Jurkowska, A. Charakterystyka sylwetki i zainteresowań uczestników turystyki birdwatchingowej w Polsce (Profile and interests of bird-watching tourists in Poland). Stud. I Mat. CEPL W Rogowie 2015, 17, 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Janeczko, E.; Łukowski, A.; Bielinis, E.; Woźnicka, M.; Janeczko, K.; Korcz, N. Not just a hobby, but a lifestyle”: Characteristics, preferences and self-perception of individuals with different levels of involvement in birdwatching. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamczyk, J. Skituring w polskich górach—Nowy produkt turystyczny? (Skitouring in polish mountains—A new offer?). Stud. I Mat. CEPL W Rogowie 2009, 11, 311–317. [Google Scholar]

- Bielański, M.; Adamski, P.; Ciapała, S.; Olewiński, M. Poza szlakowa turystyka narciarska w Tatrzańskim Parku Narodowym (Off-trial ski touring in Tatra National Park). Stud. I Mat. CEPL W Rogowie 2017, 19, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Vassiljev, P.; Bell, S. While Experiencing a Forest Trail, Variation in Landscape Is Just as Important as Content: A Virtual Reality Experiment of Cross-Country Skiing in Estonia. Land 2023, 12, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sælen, H.; Ericson, T. The recreational value of different winter conditions in Oslo forests. A choice experiment. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 131, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesiewski, A.; Lesiewski, J. Narty; Pascal: Warsaw, Poland, 2007; ISBN 9788375138153. [Google Scholar]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny (Statistics Poland). Turystyka w 2008 Roku (Tourism in 2008). 2009. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/cps/rde/xbcr/gus/kts_Turystyka_w_2008.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny (Statistics Poland). Turystyka w 2023 Roku (Tourism in 2023). 2024. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/kultura-turystyka-sport/turystyka/turystyka-w-2023-roku,1,21.html (accessed on 7 January 2025).

- Fabijański, P. Narciarstwo Biegowe. Available online: https://www.lasy.gov.pl/pl/turystyka/pomysly-na-wypoczynek-1/narciarstwo-biegowe (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Cieszewska, A.; Giedych, R.; Maksymiuk, G.; Wałdykowski, P.; Adamczyk, J. Inwentaryzacja liniowych elementów infrastruktury turystycznej na potrzeby rozwoju funkcji rekreacyjnej w lasach na przykładzie Nadleśnictwa Celestynów. (Inventory method of linear elements of tourist infrastructure for recreation development of forests Celestynów Forest District case study). Prob. Ekol. Krajobr. 2012, 34, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, J. Gdzie na Biegówki w Polsce? Najlepsze Trasy Narciarstwa Biegowego. Available online: https://triverna.pl/blog/gdzie-na-biegowki-w-polsce-najlepsze-trasy (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Szabłowski, P. Trasy Narciarstwa Biegowego. Available online: https://pisz.bialystok.lasy.gov.pl/trasy-narciarskie (accessed on 6 August 2024).

- Prószyńska-Bordas, H.; Witkowski, A.; Zieliński, S. Narciarstwo wędrówkowe w Kampinoskim Parku Narodowym (Cross-country skiing in the Kampinos National Park). Tur. I Rekr. 2012, 8, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Leśniak-Johann, M. Planowanie turystyczne według zasad rozwoju zrównoważonego na przykładzie Parku Krajobrazowego Dolina Baryczy. Ekonom. Prob. Usług 2010, 52, 621–632. [Google Scholar]

- Gołos, P. Społeczne i Ekonomiczne Aspekty Pozaprodukcyjnych Funkcji Lasu i Gospodarki Leśnej—Wyniki Badań Opinii Społecznej (Social and Economic Aspects of Non-Productive Functions of Forests and Forest Management—Results of Public Opinion Surveys); Rozprawy i Monografie; Prace Instytutu Badawczego Leśnictwa: Sękocin Stary, Poland, 2018; p. 115. ISBN 978-83-62830-68-8. [Google Scholar]

- Czajkowski, M.; Barczak, A.; Budziński, W.; Giergiczny, M.; Hanley, N. Preference and WTP stability for public forest management. For. Policy Econ. 2016, 71, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zydroń, A.; Szoszkiewicz, K.; Chwiałkowski, C. Valuing protected areas: Socioeconomic determinants of the willingness to pay for the National Park. Sustainability 2021, 13, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żylicz, T.; Giergiczny, M. Wycena Pozaprodukcyjnych Funkcji Lasu. Raport Końcowy. (Evaluation of Non-Wood Forest Functions. Final Report); Uniwersytet Warszawski, Wydział Nauk Ekonomicznych: Warszawa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barrio, M.; Loureiro, M.L. A meta-analysis of contingent valuation forest studies. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 69, 1023–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeo. Electr. 2001, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L.; Friedman, J.H.; Olshen, R.A.; Stone, C.J. Classification and regression trees. Wadsworth & Brooks/Cole Advanced Books & Software: Monterey, CA, USA,, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ripley, B.D. Pattern Recognition and Neural Networks; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; ISBN 9780511812651. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Gregory, R. Why the WTA–WTP disparity matters. Ecol. Econ. 1994, 28, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, J.K.; McConnell, K.E. A review of WTA/WTP studies. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2002, 44, 426–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, P.; Tewari, V.P.; Singh, B. WTP vs WTA For Assessing the Recreational Benefits of Urban Forests: A Case from a Modern and Planned City of a Developing Country. For. Trees Livelihoods 2008, 18, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawilińska, B. Ekonomiczna wartość obszarów chronionych. Zarys problematyki i metodyka badań (Economic value of protected areas. Problems and research methodology). Zesz. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. Krak. 2014, 12, 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Hanemann, W.M. Willingness to pay and willingness to accept: How much can they differ? Am. Econ. Rev. 1991, 81, 635–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanemann, W. National Research Counsil. Translating ecosystem functions to the value of ecosystem services—Case Studies. In Valuing Ecosystem Services: Toward Better Environmental Decision-Making; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 153–208. ISBN 0-309-09318-X. [Google Scholar]

- Koetse, M.J.; Brouwer, R. Reference Dependence Effects on WTA and WTP Value Functions and Their Disparity. Environ. Res. Econ. 2015, 65, 723–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugden, R. 1999. Alternatives to the neoclassical theory of choice. In Valuing Environmental Preferences: Theory and Practice of the Contingent Valuation Method in the US, EU and Developing Countries; Bateman, I.J., Willis, K.G., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002; pp. 259–301. ISBN 9780199248919. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, J.K.; McConnell, K.E. Willingness to accept, pay and the income effect. J. Econ. Beh. Org. 2003, 51, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H. Does Attenuating Endowment Effect Improve Efficiency? An Overview of Applications. High. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2023, 21, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matel, A.; Poskrobko, T. Contingent valuation method in terms of behavioral economics. Ekon. I Sr. 2016, 1, 35–52. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, G.; Braathen, N.A.; Groom, B.; Mourato, S. Cost Benefit Analysis and the Environment: Further Developments and Policy Use. OECD Report 2018. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/cost-benefit-analysis-and-the-environment_9789264085169-en.html (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Mitchell, R.C.; Carson, R.T. Using Surveys to Value Public Goods: The Contingent Valuation Method; Resources for the Future: Washington DC, USA, 1989; ISBN 9780915707324. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.J.; Zhao, C.W. Non-market valuation of forest resources in Guiyang City of Guizhou Province based on comparative analysis of WTP and WTA. Chin. J. Ecol. 2011, 30, 327–334. [Google Scholar]

- Doris, A.A.; Wang, R. Key Determinants of Forest-dependent Guyanese’ Willingness to Contribute to Forest Protection: An application of the Contingent Valuation Method. Intl. J. Sci. Res. Public 2018, 8, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ni, Z.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Xia, B. Public perception and preferences of small urban green infrastructures: A case study in Guangzhou, China. Urb. For. Urb. Green. 2020, 53, 126700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizaras, S.; Kavaliauskas, M.; Cinga, G.; Mizaraite, D.; Belova, O. Socio-economics Aspects of Recreational Use of Forests in Lithuania. Balt. For. 2015, 21, 308–314. [Google Scholar]

- Sirina, N.; Hua, A.; Gobert, J. What factors influence the value of an urban park within a medium–sized French conurbation? Urb. For. Urb. Green. 2017, 24, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloggy, M.R.; Escobedo, F.J.; Sánchez, J.J. The role of spatial information in peri–urban ecosystem service valuation and policy investment preferences. Land 2022, 11, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandziuk, A.; Bijak, S.; Fornal–Pieniak, B. Social preferences of financing recreational ecosystem services in forest—The case of the ‘Janowskie Forests’ Promotional Forest Complex. Sylwan 2024, 168, 674–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skłodowski, J.; Gołos, P. Wartość rekreacyjnej funkcji lasu w świetle wyników ogólnopolskiego badania opinii społecznej (Value of leisure–related function of forest in view of the results of nationwide survey in Poland). Sylwan 2016, 160, 759–766. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, A.B.; Olsen, S.B.; Lundhede, T. An economic valuation of the recreational benefits associated with nature-based forest management practices. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 80, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim, C.Y.; Chen, W.Y. Recreation–amenity use and contingent valuation of urban greenspaces in Guangzhou, China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołos, P.; Ukalska, J. Hipotetyczna gotowość finansowania publicznych funkcji lasu i gospodarki leśnej (Hypothetical readiness for financing the most important public functions of forest and forest management). Sylwan 2016, 160, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandziuk, A.; Fornal-Pieniak, B.; Stangierska, D.; Parzych, S.; Widera, K. Social Preferences of Young Adults Regarding Urban Forest Recreation Management in Warsaw, Poland. Forests 2021, 12, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandziuk, A.; Studnicki, M. Gotowość przyjęcia rekompensaty jako miara wartości nierynkowych świadczeń terenów leśnych (Willingness to Accept as a measure of non-market services of forest areas). Acta Sci. Pol. Silv. 2019, 18, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandziuk, A.; Parzych, S.; Studnicki, M.; Radomska, J.; Gruchała, A. Wycena pozaprodukcyjnych funkcji lasu metodą warunkową na przykładzie funkcji turystycznej. (Valuation of non–wood forest functions by a contingent method on the example of a tourist function). Sylwan 2019, 163, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paletto, A.; Guerrini, S.; De Meo, I. Exploring visitors’ perceptions of silvicultural treatments to increase the destination attractiveness of peri-urban forests: A case study in Tuscany Region (Italy). Urb. For. Urb. Green. 2017, 27, 314–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baciu, G.E.; Dobrotă, C.E.; Apostol, E.N. Valuing forest ecosystem services. Why is an integrative approach needed? Forests 2021, 12, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mell, I.C.; Henneberry, J.; Hehl–Lange, S.; Keskin, B. To green or not to green: Establishing the economic value of green infrastructure investments in the Wicker, Sheffield. Urb. For. Urb. Green. 2016, 18, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, M.; Budziński, W.; Campbell, D.; Giergiczny, M.; Hanley, N. Spatial Heterogeneity of Willingness to Pay for Forest Management. Environ. Res. Econ. 2017, 68, 705–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, C.; Pinto, B. Paleo-História e História Antiga das Florestas de Portugal Continental: Até à Idade Média; LPN: Lisboa, Portugal, 2007; ISBN 978-989-619-104-7. [Google Scholar]

- Krzysztofik, R.; Rahmonov, O.; Kantor-Pietraga, I.; Dragan, W. The Perception of Urban Forests in Post-Mining Areas: A Case Study of Sosnowiec-Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundersen, V.S.; Frivold, L.H. Public preferences for forest structures: A review of quantitative surveys from Finland, Norway and Sweden. Urb. For. Urb Green. 2008, 7, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Nordlund, A.M.; Olsson, O.; Westin, K. Recreation in Different Forest Settings: A Scene Preference Study. Forests 2012, 3, 923–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavárez, H.; Elbakidze, L. Valuing recreational enhancements in the San Patricio Urban Forest of Puerto Rico: A choice experiment approach. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 109, 102004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smoleński, M. Motywy podróży ekoturystycznych w lasach (Motives for ecotourist trips in forests). Sylwan 2007, 151, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törn, A.; Tolvanen, A.; Norokorpi, Y.; Tervo, R.; Siikamäki, P. Comparing the impacts of hiking, skiing and horse riding on trail and vegetation in different types of forest. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 90, 1427–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żemła, M. Winter Sports Resorts and Natural Evinronment—Systematic Literature Review Presenting Interactions between Them. Sustainability 2021, 13, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radecki, W. Ochrona Walorów Turystycznych w Prawie Polskim (Protection of Tourist Attractions in Polish Law); Wolters Kluwer: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; ISBN 9788326414954. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, T. Status i przyszłość użytkowania rekreacyjnego lasu w opinii pracowników Lasów Państwowych. (Status and future of recreational use of forests in the opinion of employees of the State Forests NFH). Sylwan 2017, 161, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).