Professional Degree Graduate Education in Forestry: Comparative Insights Across Developing and Developed Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background: Forests, Global Challenges, and the Role of Graduate Forestry Education

1.2. Gaps Between Developed and Developing Countries

1.3. Aim and Research Questions

- (1)

- How do flagship graduate forestry programs in developed and developing countries differ across key institutional dimensions, including curriculum structure, faculty and research capacity, enrolment characteristics, industry alignment, employment outcomes, and funding models?

- (2)

- What contextual and institutional factors explain the similarities and differences observed across the ten selected international cases?

- (3)

- What implications do these comparative findings have for strengthening forestry graduate education in diverse regional and economic settings?

1.4. Theoretical Framework

2. Global Status and Trends in Forestry Education

3. Methodology

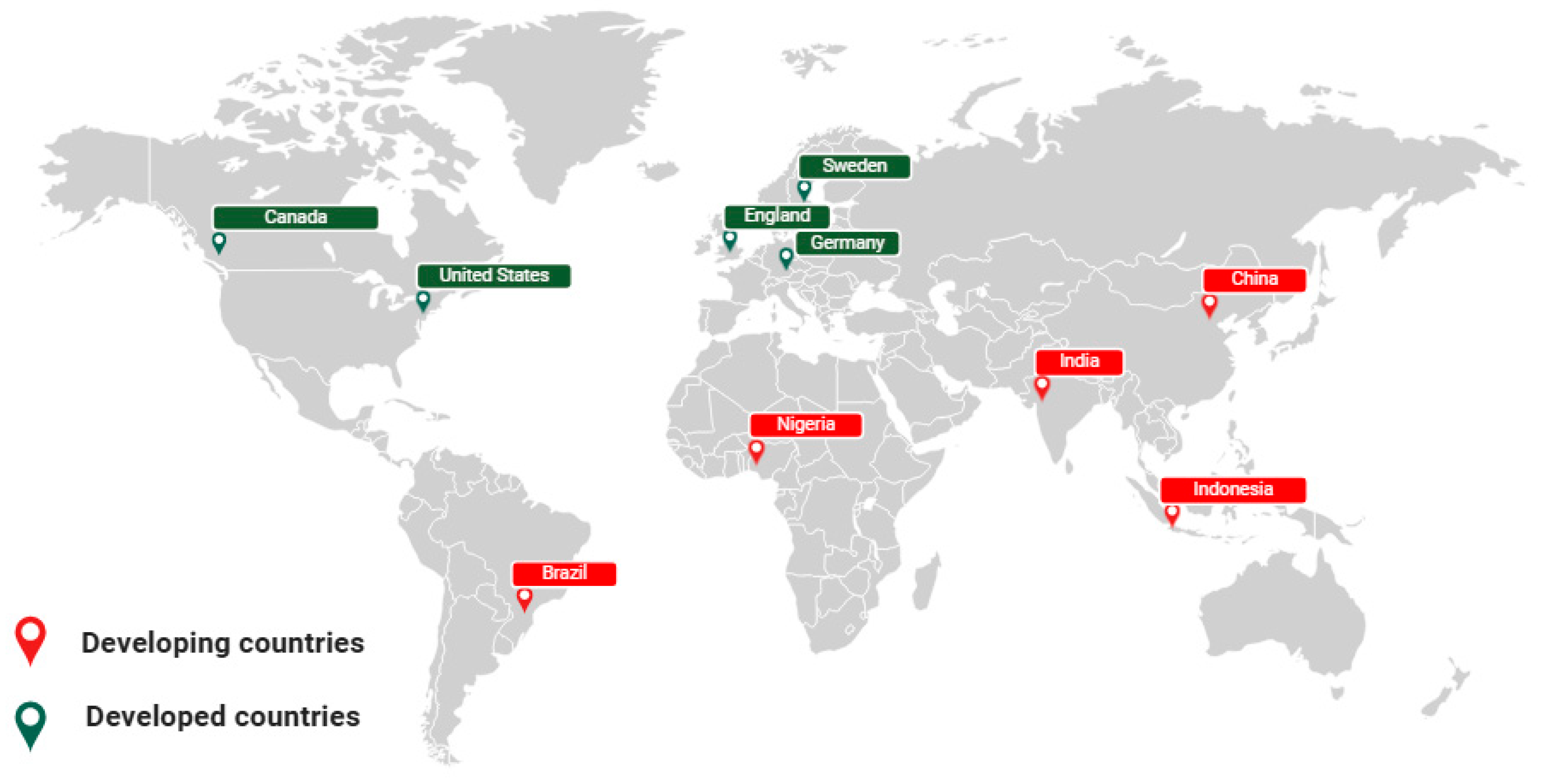

3.1. Research Design and Scope

3.2. Literature Search, Case Selection, and Data Sources

- recognized national or regional prominence in forestry education;

- a long-standing institutional history in forestry or forest-related disciplines;

- strong research output in forestry, environmental science, or related fields;

- comprehensive graduate offerings (e.g., MSc, professional master’s, or doctoral programs);

- evidence of international engagement through partnerships, joint programs, or mobility schemes.

3.3. Analytical Framework, Data Analysis

- (1)

- curriculum structure and specialization;

- (2)

- faculty profiles and research capacity;

- (3)

- industry and policy linkages;

- (4)

- infrastructure and learning resources;

- (5)

- financial models and resource allocation;

- (6)

- partnerships and mobility opportunities.

4. Results: Institutional Case Descriptions

4.1. Forestry Education in Developing Countries

4.1.1. Developing Countries Case Study Analysis

Brazil: University of São Paulo

Indonesia: Bogor Agricultural University

Nigeria: University of Ibadan

China: Beijing Forestry University

India: Indian Institute of Forest Management

4.2. Forestry Education in Developed Countries

4.2.1. Developed Countries Case Study Analysis

Canada: University of British Columbia

Sweden: Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences

United States: Yale University

United Kingdom: Bangor University

Germany: Technical University of Munich

5. Cross-Case Comparative Analysis

5.1. Curriculum Focus and Degree Structures

5.2. Graduate Enrollment Trends

5.3. Faculty Profiles and Research Specializations

5.4. Industry Alignment

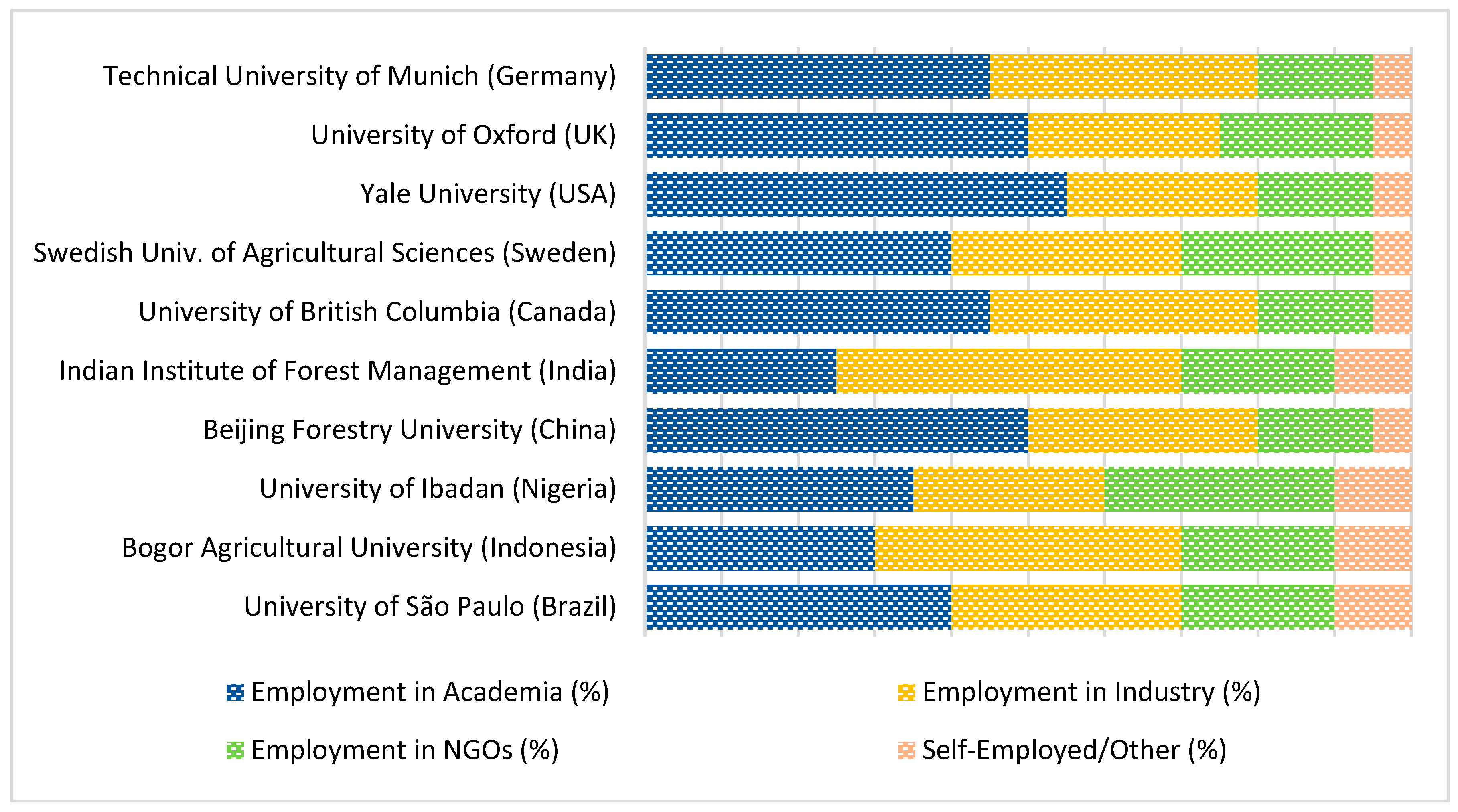

5.5. Graduate Employment Outcomes

5.6. Financial Models for Forestry Education

6. Limitations

- (1)

- Institutional Rather than National Representativeness

- (2)

- Reliance on Secondary and Publicly Available Data

- (3)

- Incomplete Standardization of Financial and Employment Data

- (4)

- Uneven Regional Representation

- (5)

- Absence of Longitudinal Perspective

7. Discussion: Interpretation of Findings in Relation to Existing Literature

8. Policy Recommendations

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Flagship Program Selection Matrix

| Country | Institution Selected | Prominence | History | Research Output | Graduate Offerings | International Engagement | Justification Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | University of São Paulo (USP)/ESALQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Oldest and most influential forestry faculty in Brazil; strong research footprint and regional leadership. |

| Indonesia | Bogor Agricultural University (IPB) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | National reference institution with extensive forestry training and international partnerships. |

| Nigeria | University of Ibadan (UI) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | Long-standing forestry program with national prominence; strong academic impact despite limited internationalization. |

| China | Beijing Forestry University (BFU) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | China’s top forestry-specialized university with strong research and global collaboration networks. |

| India | Indian Institute of Forest Management (IIFM) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Nationally recognized for professional forestry management programs with strong policy linkages. |

| Canada | University of British Columbia (UBC) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Leading North American forestry school with high global rankings and extensive graduate offerings. |

| Sweden | Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Europe’s foremost forestry research institution with long-standing tradition and strong internationalization. |

| United States | Yale School of the Environment (YSE) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Historically significant forestry school with global influence and comprehensive graduate programs. |

| United Kingdom | Bangor University | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Long-established forestry education centre with strong research and international MSc networks. |

| Germany | University of Freiburg | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | One of Europe’s oldest forestry programs with extensive international partnerships and strong research capacity. |

Appendix B. Source Audit Table

| Country | Institution/ Program | Resources for Programme Page/Handbook | Resources for Independent/ External Reports | Notes on Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | UBC—Master of International Forestry (MIF) | [109] | [110] | Used for curriculum, tuition, internship evidence. |

| USA | Yale School of the Environment–Master of Forestry (MF) | [111] | [112] | Used for capstone, accreditation, graduate outcomes. |

| UK | Bangor University—MSc Forestry | [113] | [114] | Used for accreditation, placement pathways. |

| Sweden | SLU—MSc Forest Ecology & Sustainable Management | [115] | [110] | Used for curriculum, financial model. |

| Germany | TUM—MSc Forestry & Wood Sciences | [116] | [117] | Used for tuition, scholarships, faculty profiles. |

| India | IIFM—MBA Forestry Management | [118] | [119] | Used for tuition, employment outcomes, internships. |

| China | Beijing Forestry University—Professional Master Forestry | [120] | [121] | Used for curriculum, scholarships, placement. |

| Brazil | USP/ESALQ–PPGRF | [122] | [123] | Used for curriculum, research lines, funding. |

| Indonesia | IPB University–MSc Forestry | [124] | [125] | Used for curriculum, outcomes, field practice. |

| Nigeria | University of Ibadan—MSc Forestry | [126] | [44,48] | Used for curriculum and employment outcomes. |

References

- Rodríguez-Piñeros, S.; Walji, K.; Rekola, M.; Owuor, J.A.; Lehto, A.; Tutu, S.A.; Giessen, L. Innovations in forest education: Insights from the best practices global competition. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 118, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunachalam, A.; Pandey, L. Transforming forestry education for better job prospects. Curr. Sci. 2019, 117, 748–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoungrana, I.; Mogotsi, K.K.; Temu, A.B.; Rudebjer, P.G. Rebuilding Africa’s Capacity for Agricultural Development: The Role of Tertiary Education; World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF): Nairobi, Kenya, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunsola, A.J.; Ogunsola, J.O.; Awe, F.; Fatoki, O.A.; Kolade, R.I.; Oke, O.S. Perception of Forestry as a Career Choice among Forestry Students in Nigeria. Tanzan. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 19, 167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Laurillard, D.; Kennedy, E. The Potential of MOOCs for Learning at Scale in the Global South; Centre for Global Higher Education: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kanowski, P.; Yao, D.; Wyatt, S. SDG 4: Quality Education and Forests–‘The Golden Thread’. In Sustainable Development Goals: Their Impacts on Forests and People; Katila, P., Colfer, C.J.P., de Jong, W., Galloway, G., Pacheco, P., Winkel, G., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019; pp. 108–145. [Google Scholar]

- Mika, R.; Terry, L.S. Global Assessment of Forest Education–Creation of a Global Forest Education Platform and Launch of a Joint Initiative under the Aegis of the Collaborative Partnership on Forests (FAO-ITTO-IUFRO project GCP /GLO/044/GER); Forestry Working Paper No. 32; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesterman, S.; Wardell, D.A.; Mehmood-Ul-Hassan, M.; Bourne, M. Capacity Needs Assessment of CIFOR, ICRAF and their partners for the implementation of the CGIAR Research Program on Forestry, Trees and Agroforestry (FTA): Phase II, 2017–2021; Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR): Bogor, Indonesia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M.; Adamson, B.; Mason, M. Comparative Education Research: Approaches and Methods, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zajda, J.; Majhanovich, S. (Eds.) Globalisation, Cultural Identity and Nation-Building: The Changing Paradigms; Globalisation, Comparative Education and Policy Research; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Wolhuter, C.C. Review of the Review: Constructing the Identity of Comparative Education. Res. Comp. Int. Educ. 2008, 3, 323–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, M.; Thomas, R.M. Levels of Comparison in Educational Studies: Different Insights from Different Literatures and the Value of Multilevel Analyses. Harv. Educ. Rev. 1995, 65, 472–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, J.; Tang, C. Teaching for Quality Learning at University: What the Students Does, 4th ed.; The Society for Research into Higher Education: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman, L.S. Signature pedagogies in the professions. Daedalus 2005, 134, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altbach, P. Global Perspectives on Higher Education; Johns Hopkins University: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S. Higher Education and Public Good. High. Educ. Q. 2011, 65, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.G. Challenges and strategies of forest research and education in China. Forest Sci. Technol. 2005, 1, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, K.M. Forest education and research in India: Country report. Forest Sci. Technol. 2005, 1, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Tropical Timber Organization. International Tropical Timber Organization Fellowship Programme. Available online: https://www.itto.int/top_stories/2024/07/17/itto_fellowship_programme_now_open_for_2024_applications/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Erasmus Forestry Network. Available online: https://erfonet.com/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- The SILVA Network. Available online: https://ica-silva.eu/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- University of Eastern Finland. Master of Science in European Forestry. Available online: https://sites.uef.fi/europeanforestry/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- SLU-Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Euroforester MSC with a Major in Forestry Science. Available online: https://www.slu.se/en/study/programmes-courses/masters-programmes/euroforester/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Yin, R.K. Case study research: Design and methods. Appl. Soc. Res. Methods Ser. 2013, 18, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teichler, U. Higher Education and the World of Work Conceptual Frameworks, Comparative Perspectives, Empirical Findings; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 16. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, B.R. The entrepreneurial university: Demand and response. Tert. Educ. Manag. 1998, 4, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. Breaking the Gridlock: A Snapshot of the 2023/2024 Human Development Report; United Nations Development Programme: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank Group. World Bank Country and Lending Groups–Country Classification; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ratnasingam, J.; Ioras, F.; Vacalie, C.C.; Wenming, L. The future of professional forestry education: Trends and challenges from the malaysian perspective. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj. Napoca 2013, 41, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, A. How to beat the brain drain and foster home expertise. Nature 2024, 634, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndiangui, P. From Brain Drain to Brain Gain: The Battle Against Talent Drain. J. Cult. Values Educ. 2020, 4, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temu, A.; Okali, D.; Bishaw, B. Forestry education, training and professional development in Africa. Int. For. Rev. 2006, 8, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maryawan, I.; Rochsas, A. Pendidikan dan Penelitian Kehutanan di Berbagai Belahan Dunia: Sebuah Tinjauan Literatur. J. Sci. Appl. Technol. 2022, 6, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, W.; Huang, K.; Zhuo, Y.; Kleine, M.; Wang, G.; Liu, W.; Xu, G. A comparison of forestry continuing education academic degree programs. Forests 2021, 12, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.S.; Sojin, Y.; Yeo-Chang, Y.; Donsavanh, B.; Phetlumphan, B. Needs assessment of forestry education in Laos: The case of Souphanouvong University. J. For. Res. 2019, 24, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyinza, M.; Vedeld, P. Restore, reform or transform forestry education in Uganda? Makerere J. High. Educ. 2009, 2, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakamada, R.; Ferraz, S.F.d.B.; Mattos, E.M.; Sulbarán-Rangel, B. Trends in Brazil’s Forestry Education: Overview of the Forest Engineering Programs. Forests 2023, 14, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakamada, R.; Ferraz, S.F.d.B.; Sulbarán-Rangel, B.; Lucena, L.; Hinestroza, H.P. Trends in Brazil’s Forestry Education—Part 3: Employment Patterns of Forest Engineering Graduates from Two Public Universities in the Last 15 Years. Forests 2023, 14, 1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakamada, R.; Ferraz, S.F.d.B.; Sulbaran-Rangel, B. Trends in Brazil’s Forestry Education—Part 2: Mismatch between Training and Forest Sector Demands. Forests 2023, 14, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riyanto, S.; Ismail, M.H.; Bidin, S. A Review of Social Knowledge among Forestry Graduates in Forest Education Curriculum in Indonesia; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 204–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L. Environmentalism and education for sustainability in Indonesia. Indones. Malay World 2018, 46, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alao, J.S. Repositioning forestry education in Nigeria. Electron. J. Environ. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 9, 284–292. [Google Scholar]

- Adeyanju, S.; Adesuyi, O.; Offiah, C.; Fasalejo, O.; Ogunlade, B. Where are the foresters? The influx of forestry graduates to non-forestry jobs in Nigeria. In Proceedings of the XV World Forestry Congress, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2–6 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Akande, A.J. Challenges to Forestry Education: A Perspective from Nigeria; World Agroforestry Centre: Nairobi, Kenya, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lekah, A.; Mala, W.; Ofosu, S.; Boadu, K.B.; Onotunji, A.B.; Shonowo, D.A.; Babalola, F.D. Global Outlook on Forest Education: A Special Report: Forest Education in Africa; Nigeria Country Report; Online Publication, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, L.; Agbeja, B.O. 8 Renewable Natural Resources Education in Nigeria: University of Ibadan Experience. In New Perspectives in Forestry Education; ICRAF: Nairoby, Kenya, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Onatunji, A.B.; Owuor, J.A.; Rodriguez-Piñeros, S.; Babalola, F.D.; Akello, S.; Adeyemi, O. Building a Successful Forestry Career in Africa: Inspirational Stories and Opportunities; International Union of Forest Research Organizations: Vienna, Austria, 2021; 120p. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, M.; Ahponen, P.; Tahvanainen, L.; Gritten, D.; Mola-Yudego, B.; Pelkonen, P. Chinese university students’ knowledge and attitudes regarding forest bio-energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 3649–3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NDRC-National Development and Reform Commission. Medium and Long Term Development Plan for Renewable Energy; NDRC: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, P.J.; Roberts, R.W. Forestry Education in China. For. Chron. 1988, 64, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The University of British Columbia; Faculty of Forestry. APFNet, Growing Higher Forestry Education in a Changing World: Analysis of Higher Forestry Education in the Asia-Pacific Region; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ginwal, H.S.; Rai, K.C. Forestry Research, Education, and Extension in India. In Textbook of Forest Science; Mandal, A.K., Nicodemus, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.L.; Ward, D. Professional Education in Forestry Incorporating Text from the First Edition of Commonwealth Forests on Technical Education in Forestry. 2010. Available online: https://www.cfa-international.org/docs/Commonwealth%20Forests%202010/cfa_layout_web_chapter5.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Pelkonen, P. Challenges and strategies for forest education and research in Finland. For. Sci. Technol. 2005, 1, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arevalo, J.; Mola-Yudego, B.; Pelkonen, P.; Qu, M. Students’ views on forestry education: A cross-national comparison across three universities in Brazil, China and Finland. For. Policy Econ. 2012, 25, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J.L. Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and training in forestry and forest research. For. Chron. 2005, 81, 324–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erskine, J.M. Agroforestry: Its development as a sustainable, productive land-use system for low-resource farmers in southern Africa. For. Ecol. Manag. 1991, 45, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chima, U.D.; Sobere, P.G. Secondary School Students’ Perception of Forestry and Wildlife Management in Rivers State, Nigeria. J. Agric. Soc. Res. 2011, 11, 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nordin, V.J.; Comeau, R. Forest resources education in Canada. For. Chron. 2003, 79, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apsey, M.; Laishley, D.; Nordin, V.; Paille, G. The perpetual forest: Using lessons from the past to sustain Canada’s forests in the future. For. Chron. 2000, 76, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbout, C. Forestry education in Canada. For. Chron. 1997, 73, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P. Aboriginal peoples and issues in forestry education in Canada: Breaking new ground. For. Chron. 2002, 78, 250–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UBC-University of British Columbia; Facutly of Forestry. Bachelor of Indigenous Land Stewardship. Available online: https://forestry.ubc.ca/future-students/undergraduate/indigenous-land-stewardship/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- UBC-University of British Columbia; Faculty of Forestry. Master of International Forestry (MIF). Retrived 2025. Available online: https://www.grad.ubc.ca/prospective-students/graduate-degree-programs/master-international-forestry (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Bergqvist, G.; Sugg, A.; Downie, B. Forestry education in Sweden. For. Chron. 1989, 65, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hånell, B.; Magnusson, T.; Hallgren, J.E.; Karlsson, A. Swedish forest research and higher education-challenging issues and future strategies of forest research and education in Sweden. For. Sci. Technol. 2005, 1, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SLU. The Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences-Forester Program (Jägmästarprogrammet). Available online: https://student.slu.se/studier/kurser-och-program/program-pa-grundniva/jagmastare/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Jakobsson, R.; Olofsson, E.; Ambrose-Oji, B. Growing higher forestry education in a changing world. Scand. J. For. Res. 2020, 36, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelstrand, M. Developments in Swedish forest policy and administration-from a ‘policy of restriction’ toward a ‘policy of cooperation’. Scand. J. For. Res. 2012, 27, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, C.; Lindkvist, A.; Öhman, K.; Nordström, E.M. Governing Competing Demands for Forest Resources in Sweden. Forests 2011, 2, 218–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemelä, J.; Young, J.; Alard, D.; Askasibar, M.; Henle, K.; Johnson, R.; Kurttila, M.; Larsson, T.-B.; Matouch, S.; Nowicki, P.; et al. Identifying, managing and monitoring conflicts between forest biodiversity conservation and other human interests in Europe. For. Policy Econ. 2005, 7, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Götmark, F. Conflicts in conservation: Woodland key habitats, authorities and private forest owners in Sweden. Scand. J. For. Res. 2009, 24, 504–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blennow, K.; Persson, J.; Tomé, M.; Hanewinkel, M. Climate Change: Believing and Seeing Implies Adapting. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e50182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertog, I.M.; Brogaard, S.; Krause, T. Barriers to expanding continuous cover forestry in Sweden for delivering multiple ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2022, 53, 101392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sample, V.A.; Bixler, R.P.; McDonough, M.H.; Bullard, S.H.; Snieckus, M.M. The promise and performance of forestry education in the united states: Results of a survey of forestry employers, graduates, and educators. J. For. 2015, 113, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De’arman, K.J.; York, R.F. ‘Society-Ready’ and ‘Fire-Ready’ Forestry Education in the United States: Interdisciplinary Discussion in Forestry Course Textbooks. J. For. 2021, 119, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yale. Yale School of the Environment/Master of Forestry—MF. Available online: https://environment.yale.edu/academics/masters/mf/mf-curriculum-courses (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Yale. Yale School of the Environment/Master of Environmental Management—MEM. Available online: https://environment.yale.edu/academics/masters/mem (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Kelly, E.C.; Brown, G. Who are we educating and what should they know? An assessment of forestry education in California. J. For. 2019, 117, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, K.L.; Redelsheimer, C.L. Divergent trends in accredited forestry programs in the United States: Implications for research and education. J. For. 2012, 110, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coufal, J.E. Forestry: Profession, professional, professionalism. J. For. 2019, 117, 180–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, J.; Plenderleith, K.; Howe, R.; Freer-Smith, P. Forest education and research in the United Kingdom. For. Sci. Technol. 2005, 1, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangor University. Development of Forestry at Bangor University: An international dimension; School of Natural Sciences. Available online: https://www.bangor.ac.uk/sites/default/files/migrated-files/natural-sciences/courses/distancelearning/documents/10-12CFSummer2019Bangor.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Walmsley, J.; Savill, P.; Burley, J.; Evans, J.; Horsey, R.; Leslie, A.; Falck, J.; Innes, J.; Waterson, J. Forestry in British Higher Education: A tale of decline and regeneration. Q. J. For. 2015, 109, 268–273. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, A.D.; Wilson, E.R.; Starr, C.B. The current state of professional forestry education in the United Kingdom. Int. For. Rev. 2006, 8, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Gadow, K. Forest research and education in Germany. For. Sci. Technol. 2005, 1, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Gadow, K. Adapting silvicultural management systems to urban forests. Urban For. Urban Green 2002, 1, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.C. Forestry Education in the United States; Forest Resources Librarian; University of Washington Libraries: Seattle, WA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- TUM. Technical University of Munich-School of Life Sciences/M.Sc. Forest and Wood Science. Available online: https://www.ls.tum.de/en/ls/studies/courses-and-programs/forest-and-wood-science-msc/ (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- University of British Columbia. Master of Applied Science in Forestry. Faculty of Forestry Graduate Studies. 2024. Available online: https://www.grad.ubc.ca/prospective-students/graduate-degree-programs/master-of-applied-science-forestry (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Yale School of the Environment. Welcome, YSE Class of 2027. Available online: https://environment.yale.edu/news/article/welcome-yse-class-2027 (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. Annual report 2023. Uppsala: SLU. Available online: https://www.slu.se/globalassets/slu.se/om-slu/organisation/institutioner/stad-och-land/dokument/2023annualreport.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- China Higher Education Student Information (CHSI). Beijing Forestry University Graduate Admissions Statistics. Available online: https://yz.chsi.com.cn/sch/tjzc--method-viewPub,infoId-3412879349,categoryId-670568,schId-367895,mindex-11.dhtml (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Indian Institute of Forest Management. MBA (Forestry Management) Enrolment and Placement Report 2023–2024. Bhopal: IIFM. Available online: https://iifm.ac.in/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- University of Ibadan. Student Enrolment Statistics, Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources (2022/2023 Session). Postgraduate College/Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources. Available online: https://pgcollege.ui.edu.ng/program.php?department=Forest%20Production%20and%20Products (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- University of Sao Paulo (USP); Luiz de Quieroz College of Agriculture (ESALQ). Postgraduate Program in Forest Resources (PPGRF). Available online: https://www.esalq.usp.br/pg/programas/recursos-florestais/principal (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Yale School of the Environment. LinkedIn Alumni Insights–Yale School of the Environment. 2024. Available online: https://www.linkedin.com/school/yaleenvironment/people (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- World Bank. Green Jobs and Higher Education Alignment in the Global South. 2021. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/jobs (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Indian Institute of Forest Management. Alumni Placement Report; Indian Institute of Forest Management: Bhopal, India, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, B.; Zhang, M.; Li, S.; Xie, L.; Xie, B.; Chen, L. How Digital Intelligence Integration Boosts Forestry Ecological Productivity: Evidence from China. Forests 2025, 16, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.R.; Zunain, S.; Faraz, M.; Shujaa, T.B. Empowering Entrepreneurship Education with Digital Technologies Tools. Qlantic Qlantic J. Soc. Sci. 2025, 6, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akalibey, S.; Hlaváčková, P.; Schneider, J.; Fialová, J.; Darkwah, S.; Ahenkan, A. Integrating indigenous knowledge and culture in sustainable forest management via global environmental policies. J. For. Sci. 2024, 70, 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. World Development Report 2019: The Changing Nature of Work. 2019. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1328-3 (accessed on 8 May 2025). [CrossRef]

- UNEP-FI Annual Overview 07/2019–12/2020. 2019. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2020-Annual-Overview.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Pedro, F.; Galan, V. International Cooperation to Enhance Synergies. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Higher Education, Barcelona, Spain, 18–20 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. Good Practices in South-South and Triangular Cooperation for Sustainable Development; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 4. [Google Scholar]

- Kacprzak, A. Guidelines on the Promotion of Green Jobs in Forestry; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- UBC Faculty of Forestry. Master of International Forestry: Programme Requirements & Internship/Project. Available online: https://forestry.ubc.ca/future-students/graduate/profession-al-masters-degrees/master-of-international-forestry/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- FAO. Regional Assessment Of Forest Education In Europe. 2021. Available online: www.fao.org/publications (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- Yale YSE. MF Curriculum and Outcomes. Available online: https://environment.yale.edu/academics/masters/mf (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- SAF. Committee on Accreditation Actions. 2024. Available online: https://www.eforester.org/Main/Certification_Education/Accreditation/Committees_on_Accreditation/Main/Accreditation/Committees_on_Accreditation.aspx?hkey=130cf91a-0ed5-44b0-9f8d-e001b2d5a39f (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Bangor University. MSc Forestry: Programme and Accreditation. Available online: https://www.bangor.ac.uk/study/postgraduate/forestry (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- ICF. Forestry Sector Skills Plan. Available online: https://charteredforesters.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Forestry-Sector-Skills-Plan-2025.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- SLU Admissions. Programme Description. Available online: https://www.slu.se/en/study/programmes-courses/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- TUM. Programme Description and Optional Internship. Available online: https://www.ls.tum.de/en/ls/studies/courses-and-programs/forest-and-wood-science-msc/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- DAAD. Study in Germany–Tuition & Aid. Available online: https://www.daad.de/en/studying-in-germany/ (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- IIFM. Placement Brochure 2023–2024. Available online: https://iifm.ac.in (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Shiksha. Programme Fees Overview. Available online: https://www.shiksha.com/studyabroad/scholarships/masters-courses?ct=2 (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- BFU. Programme Handbook and MOFCOM Programme Page. Available online: https://www.china-aibo.cn/en/info/1005/1497.htm (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- CSC. CSC Detailed Application Guide. 2024. Available online: https://www.jaist.ac.jp/admissions/data/Application%20Guide_JAIST-CSC%202024.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- ESALQ/USP. Postgraduate Program in Forest Resources. Available online: https://www.esalq.usp.br/pg/programas/recursos-florestais/en/academics/courses (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- CAPES. CAPES Fellowship. Available online: https://globalpartners.purdue.edu/global-partnerships/brazil/capes.html (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- IPB. Faculty of Forestry and Environment Website. Available online: https://manhut.ipb.ac.id (accessed on 16 March 2025).

- Shanahan, M.; Saengcharnchai, S.; Atkinson, J.; Ganz, D. Regional Assessment of Forest Education in Asia and the Pacific. Rome, 2021. Available online: http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/mediation/rules (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- UI. Faculty of Renewable Natural Resources Page. Available online: https://rnrs.ui.edu.ng (accessed on 16 March 2025).

| Country | Region | Income Group | HDI (2022) | Representative Institution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | Latin America | Upper-middle | 0.754 | University of São Paulo |

| Indonesia | Southeast Asia | Lower-middle | 0.705 | Bogor Agricultural University |

| Nigeria | Africa | Lower-middle | 0.535 | University of Ibadan |

| China | East Asia | Upper-middle | 0.768 | Beijing Forestry University |

| India | South Asia | Lower-middle | 0.633 | Indian Institute of Forest Management |

| Canada | North America | High | 0.929 | University of British Columbia |

| Sweden | Europe | High | 0.949 | Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences |

| United States | North America | High | 0.921 | Yale University |

| United Kingdom | Europe | High | 0.929 | Bangor University |

| Germany | Europe | High | 0.942 | Technical University of Munich |

| Country | University/ Program | Degree Structure | Curriculum Focus Areas | Notes/Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | USP–ESALQ, PPGRF | MSc (2 yrs, thesis); PhD (4 yrs) | Silviculture, forest management, forest products, conservation, policy | CAPES-accredited graduate program; research-based |

| Indonesia | IPB University, Master in Forestry | MSc (2 yrs, coursework + thesis) | Silviculture, biodiversity, plantation forestry, agroforestry, forest policy | Internships common in concessions/REDD+ |

| Nigeria | University of Ibadan, MSc Forestry | MSc (18 months–2 yrs, coursework + thesis) | Forest management, forest economics, social/environmental forestry, products | Nigeria’s oldest forestry MSc |

| China | BFU, Master of Forestry | Professional master (3 yrs, applied project) | Silviculture, engineering, GIS, restoration, NFPP monitoring | National flagship professional degree |

| India | IIFM, MBA-FM | MBA (2 yrs, course + internship) | Forestry management, climate change, policy, governance, development | Recognized as professional degree |

| Canada | UBC, MIF | Professional master (10–12 months, coursework + capstone) | International forestry, markets, governance, community forestry | SAF-accredited; capstone project |

| USA | Yale YSE, MF | Professional master (2 yrs, coursework + capstone) | Silviculture, forest management planning, policy, field training | SAF-accredited; field school |

| UK | Bangor, MSc Forestry | Taught MSc (1 yr FT, 2 yrs PT) | Silviculture, forest ecology, GIS, economics, management planning | Accredited by ICF |

| Sweden | SLU, MSc FESM | MSc (2 yrs, 120 credits, thesis) | Forest ecology, silviculture, conservation, sustainable management | Erasmus/SILVA links |

| Germany | TUM, MSc Forest & Wood Sciences | MSc (2 yrs, coursework + thesis) | Forest ecology, wood science, silviculture, economics, policy | Pathway to professional service |

| Country | Institution/Program | Metric (Scope) | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | UBC MSc Forestry | Enrolled headcount (program) | 2023–2024 | 107 (Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies) |

| Canada | UBC MASc Forestry | Enrolled headcount (program) | current | 15 (Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies) |

| USA | Yale YSE–MF | Incoming class (intake) | 2024–2025 | 13 (of 147 master’s) (Yale School of the Environment) |

| UK | Bangor MSc Environmental Forestry | Cumulative graduates (throughput) | 1980s–2021 | 835 (FT MSc, 41 yrs) (Bangor University) |

| Sweden | SLU (all master’s) | New master’s registered (univ) | 2023 | 337 (SLU.SE) |

| Sweden | SLU (all 1st/2nd cycle) | FTE (target period) | 2022–2024 | 12,677 FTE (SLU.SE) |

| Germany | TUM M.Sc. Forest & Wood Science | ND (no public headcount) | — | (program info only) (TUM Weihenstephan) |

| Brazil | ESALQ/USP PPGRF | Degrees awarded (completions) | 2025 YTD | MSc 7; PhD 9 (esalq.usp.br) |

| Indonesia | IPB–Dept. Forest Management | Grad students (dept total) | current | ~55 (M + PhD) (IPB University) |

| Nigeria | Univ. of Ibadan–FRNR | Faculty headcount (all levels) | 2022/2023 | 671 (University of Ibadan) |

| China | BFU (university) | Master’s exam applicants | 2024 | 9000+ (applicants) (Dxsbb) |

| India | IIFM MBA (FM) | Enrolled (MBA FM) | 2023–2024 | 201 (National CAMPA) |

| Country | University/ Program | Faculty Size (Approx) | Research Specializations | Notes/Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | USP–ESALQ, PPGRF | ~30+ faculty (6 lines of research) | Silviculture, forest ecology, forest products, forest economics, conservation policy, biometrics | CAPES directory; ESALQ program guide |

| Indonesia | IPB University | ~25+ forestry faculty | Silviculture, tropical forestry, forest economics, biodiversity, governance | Faculty of Forestry & Environment profile |

| Nigeria | University of Ibadan | ND (public data limited) | Social forestry, forest economics, ecology, wildlife management | Described in faculty profiles; not systematically published |

| China | Beijing Forestry University | ~60+ in forestry school | Silviculture, forest engineering, remote sensing/GIS, forest policy, restoration | BFU faculty directories |

| India | IIFM | ~25 faculty | Forest management, environment policy, sustainability, climate governance | MBA-FM faculty listing |

| Canada | UBC Faculty of Forestry | ~80+ professors | Forest genetics, silviculture, forest economics, climate/forest policy, urban forestry | Faculty of Forestry staff page |

| USA | Yale YSE | ~45 core faculty | Silviculture, forest ecology, tropical forestry, forest economics, governance | Faculty profiles |

| UK | Bangor University | ~20 staff in forestry | Silviculture, ecology, GIS, forest operations, policy | School of Natural Sciences faculty |

| Sweden | SLU | ~40+ forestry faculty | Forest ecology, management, conservation, climate impacts, silviculture | SLU department pages |

| Germany | TUM | ~35+ forestry professors | Forest ecology, wood science, technology, policy, forest genetics | TUM School of Life Sciences directory |

| Country | Program (Institution) | Internship/ Practicum (Required) | Capstone/ Client Project | Professional Accreditation | Work Placement Advertised | Explicit Partnerships/Practice Bases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | UBC—Master of International Forestry (MIF) | ✔ | ✔ | — | ◑ | ◑ |

| USA | Yale—Master of Forestry (MF) | ◑ | ✔ | ✔ | ◑ | — |

| UK | Bangor—MSc Forestry | ◑ | — | ✔ | ◑ | ◑ |

| Sweden | SLU—MSc Forest Ecology & Sustainable Management | — | — | — | ◑ | ◑ |

| Germany | TUM—MSc Forest & Wood Sciences | ◑ (optional) | — | — | ◑ | ◑ |

| India | IIFM–MBA-FM | ✔ | ✔ | — | ✔ | ◑ |

| China | BFU—Professional Master of Forestry | — | — | — | ◑ | ✔ |

| Brazil | USP/ESALQ–PPGRF | — | — | — | — | ◑ |

| Indonesia | IPB—Master of Forestry | — | — | — | ◑ | ◑ |

| Nigeria | Univ. of Ibadan–MSc Forestry | ◑ | — | — | ◑ | — |

| Universities | Endowment and Investments | Tuition and Fees | Government Grants | Private Sector Partnerships | Philanthropy and Donations | Research Grants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YU (USA) | ≈30%–40% | ≈20%–25% | 15%–20% | ≈10%–15% | ≈15%–20% | ≈30%–35% |

| Bangor (UK) | ≈40%–45% | ≈15%–20% | ≈25%–30% | ≈10%–15% | 10%–15% | 30%–35% |

| SLU (Sweden) | Minimal | ≈5%–10% | ≈50%–60% | ≈5%–10% | ≈5%–10% | 20%–30% |

| UBC (Canada) | ≈10%–15% | ≈20%–25% | ≈40%–45% | ≈10%–15% | 5%–10% | ≈20%–25% |

| TUM (Germany) | 5%–10% | ≈5%–10% | 40%–50% | ≈10%–15% | ≈5%–10% | ≈20%–25% |

| BFU (China) | Minimal or non-existent | ≈10%–15% | ≈40%–50% | 10%–15% | ≈5%–10% | 15%–20% |

| USP (Brazil) | Minimal or absent. | ≈5%–10% | ≈60%–70% | ≈5%–10% | ≈5%–10% | 15%–20% |

| UI (Nigeria) | Minimal or non-existent | ≈5%–10% | ≈70%–80% | ≈5%–10% | ≈5%–10% | 10%–15% |

| IPB (Indonesia) | Minimal or non-existent | ≈10%–15% | ≈60%–70% | ≈5%–10% | ≈5%–10% | ≈15%–20% |

| IIFM (India) | Minimal or non-existent | ≈15%–20% | ≈60%–70% | ≈5%–10% | ≈5%–10% | 10%–15% |

| Policy Focus | Developing Countries | Developed Countries | Joint Global Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curriculum Modernization | Update curricula to include digital forestry, soft skills, and entrepreneurship. | Increase the integration of local ecological knowledge and community-based management. | Develop modular, flexible curricula through international co-design platforms. |

| Funding Models | Diversify funding beyond state budgets through private sector partnerships and alumni networks. | Strengthen philanthropic support and public–private research funding alignment. | Launch global forest education funds (via FAO/IUFRO/UNEP) for cross-border training and exchange. |

| International Collaboration | Expand faculty exchange, joint research, and dual-degree programs. | Provide mentorship and capacity-building support for institutions in developing countries. | Foster developing-developing and developing-developed institutional networks on sustainable forestry training. |

| Workforce Alignment | Build strong feedback loops with forest-based industries and green employers. | Incorporate leadership, entrepreneurship, and global policy skills into training. | Coordinate graduate tracking and job market data via global observatories. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, T.; Radani, Y.; Dai, T.; Hou, W.; Yang, L. Professional Degree Graduate Education in Forestry: Comparative Insights Across Developing and Developed Countries. Forests 2025, 16, 1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121875

Wang T, Radani Y, Dai T, Hou W, Yang L. Professional Degree Graduate Education in Forestry: Comparative Insights Across Developing and Developed Countries. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121875

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Taojing, Yasmina Radani, Tingting Dai, Wenjun Hou, and Liming Yang. 2025. "Professional Degree Graduate Education in Forestry: Comparative Insights Across Developing and Developed Countries" Forests 16, no. 12: 1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121875

APA StyleWang, T., Radani, Y., Dai, T., Hou, W., & Yang, L. (2025). Professional Degree Graduate Education in Forestry: Comparative Insights Across Developing and Developed Countries. Forests, 16(12), 1875. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121875