Influencing Factor Analysis of Vegetation Spatio-Temporal Variability in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region Based on Interpretable Machine Learning

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

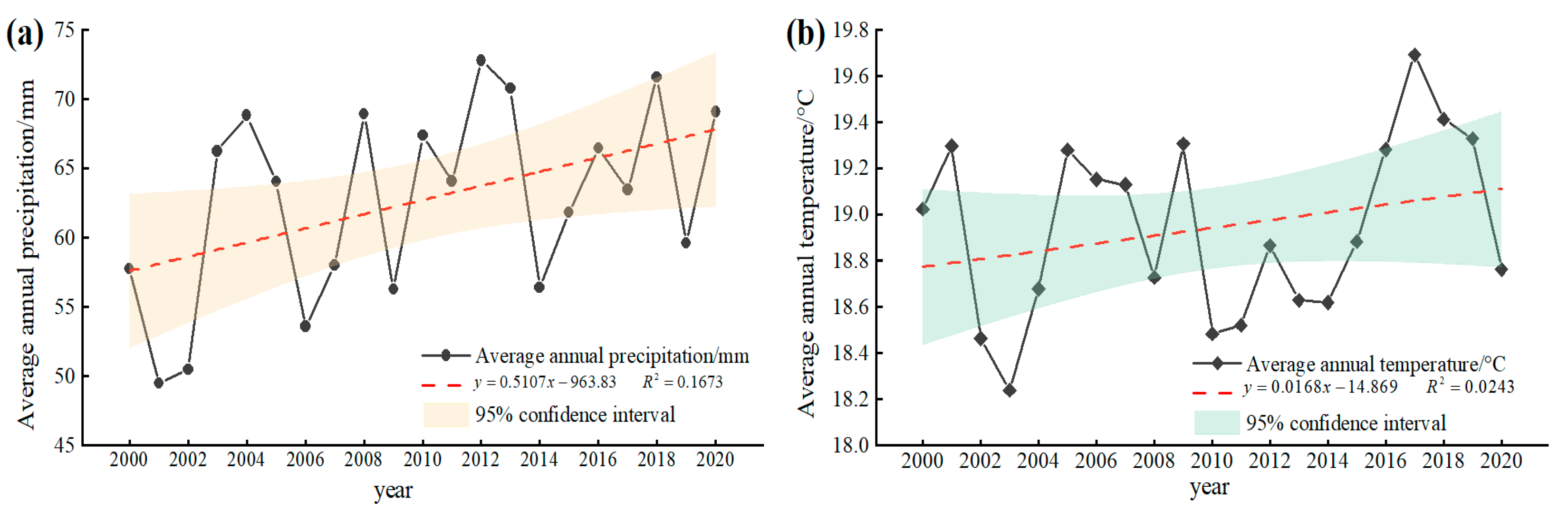

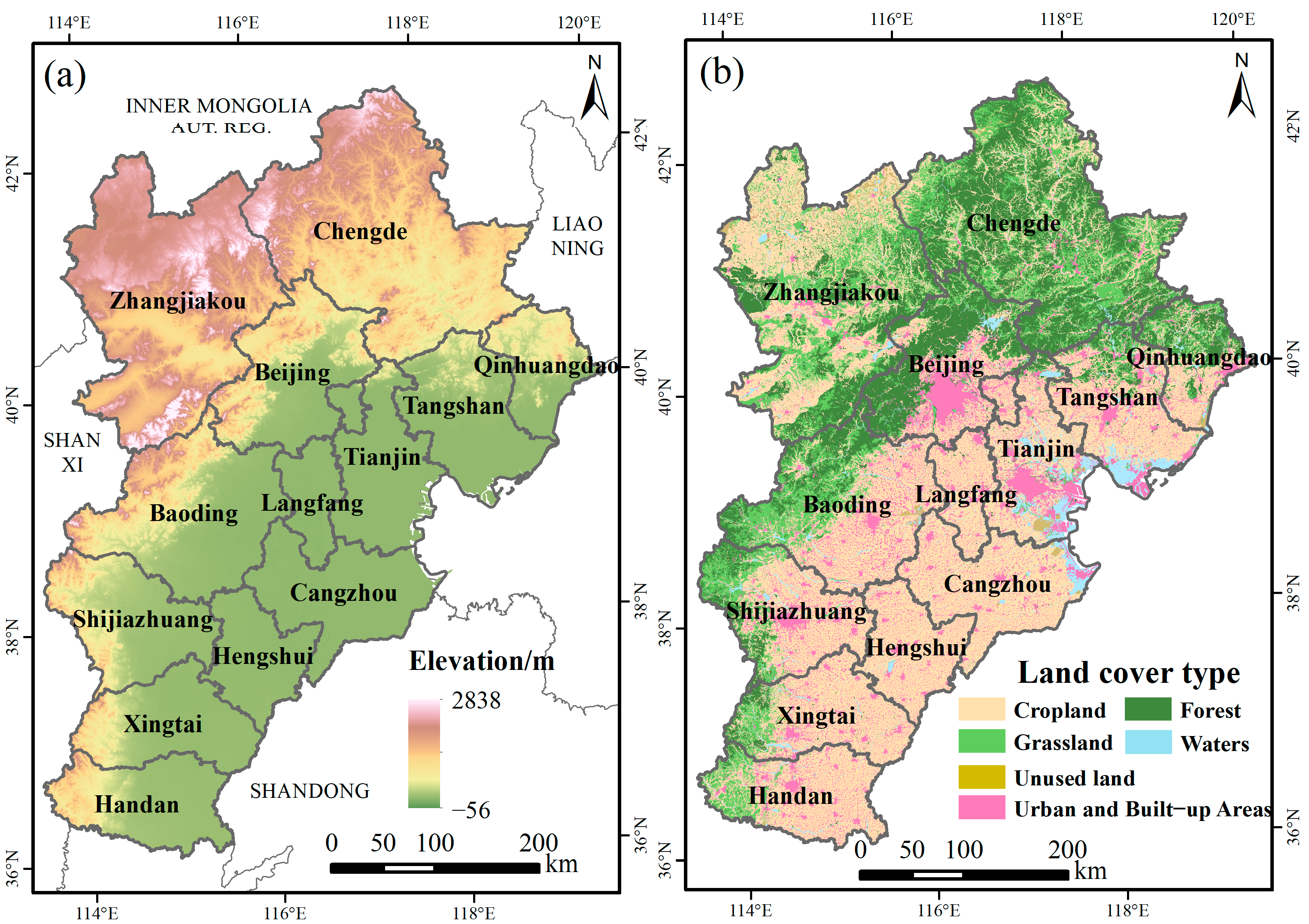

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Analysis of Vegetation Change Trends

2.3.2. Machine Learning Model

2.3.3. Model Parameter Optimization and Evaluation

2.3.4. SHapley Additive ExPlanation

3. Results

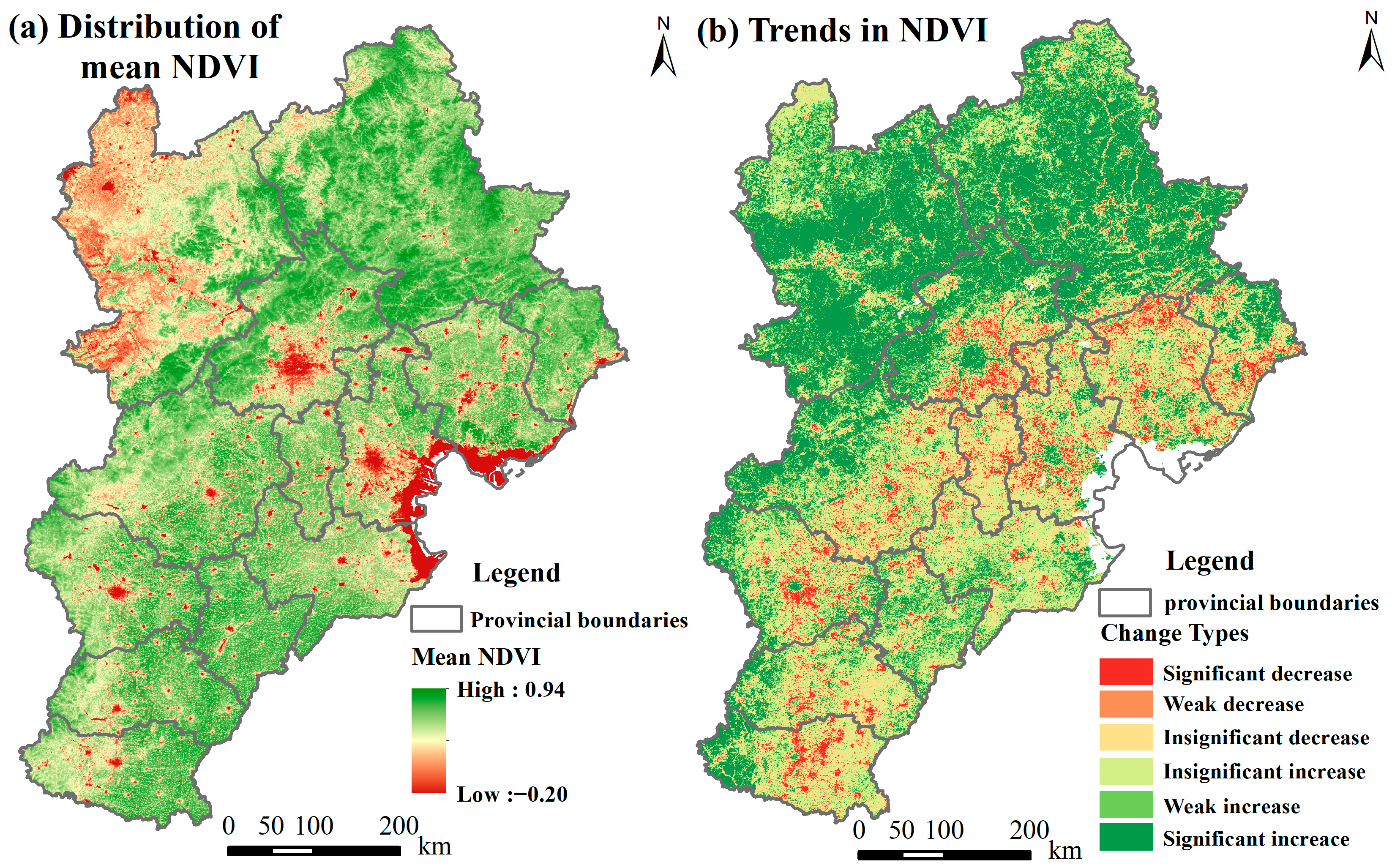

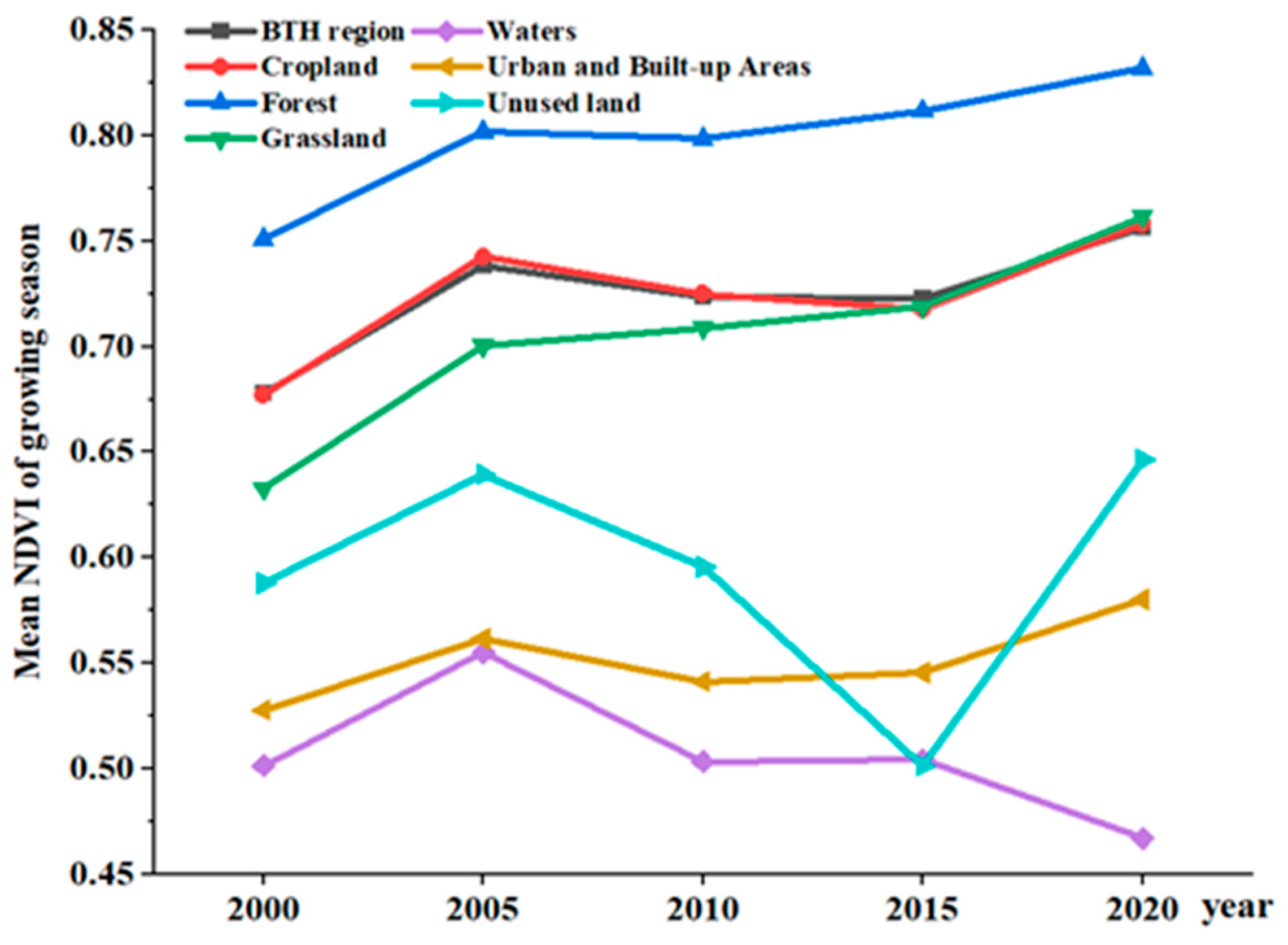

3.1. Spatio-Temporal Changes in the NDVI

3.2. Model Comparison and Result Validation

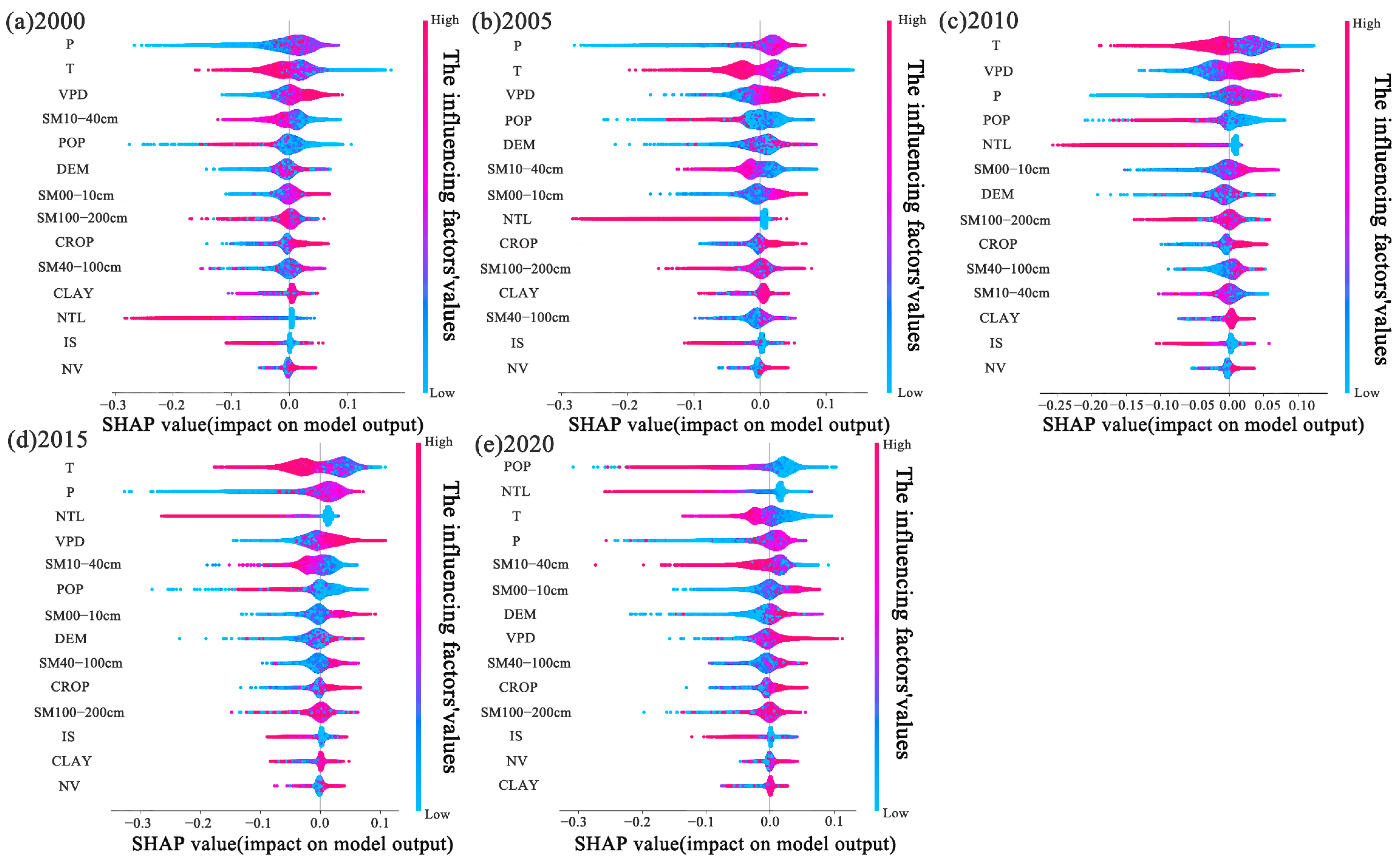

3.3. Importance Analysis of Influencing Factors

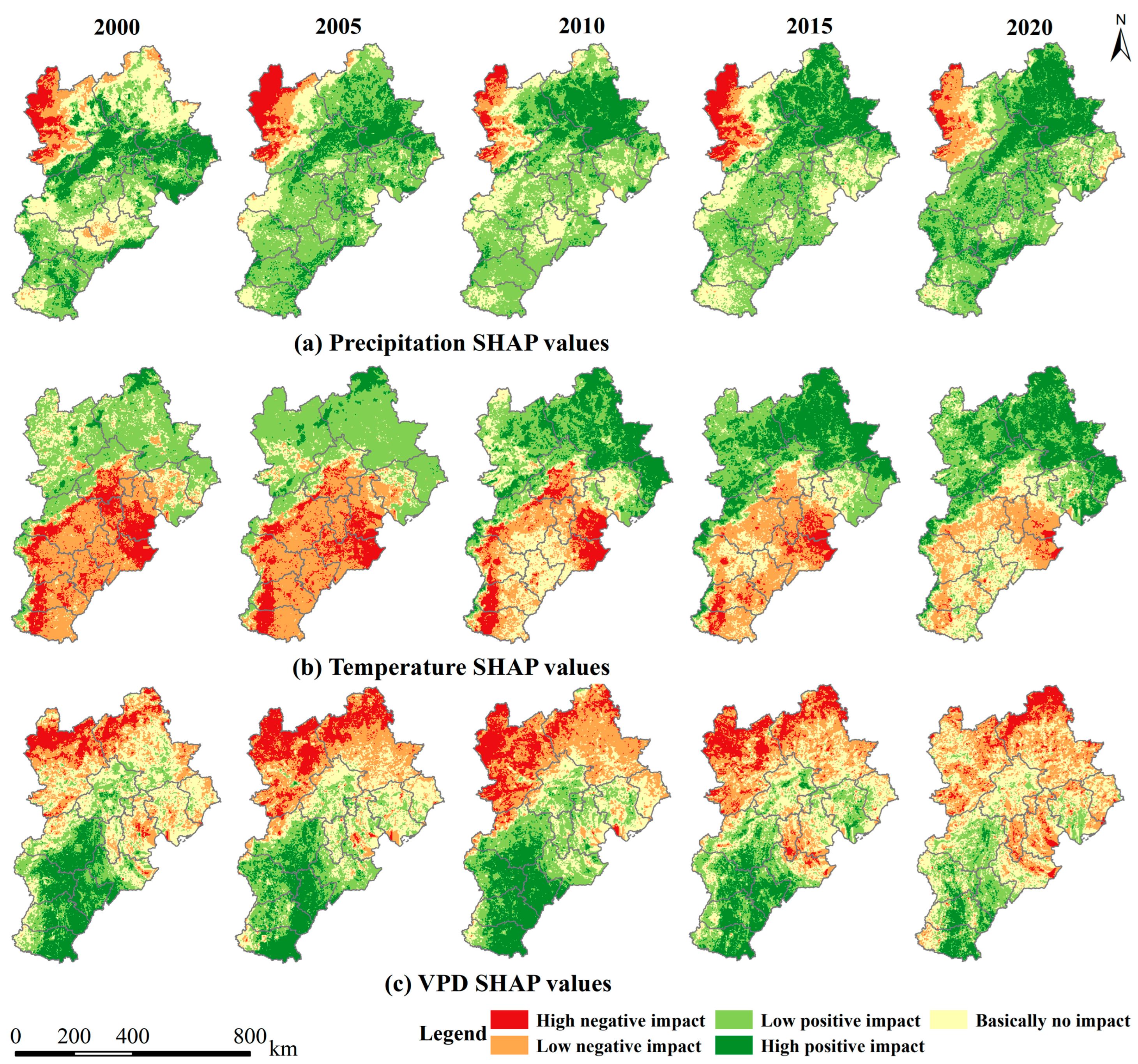

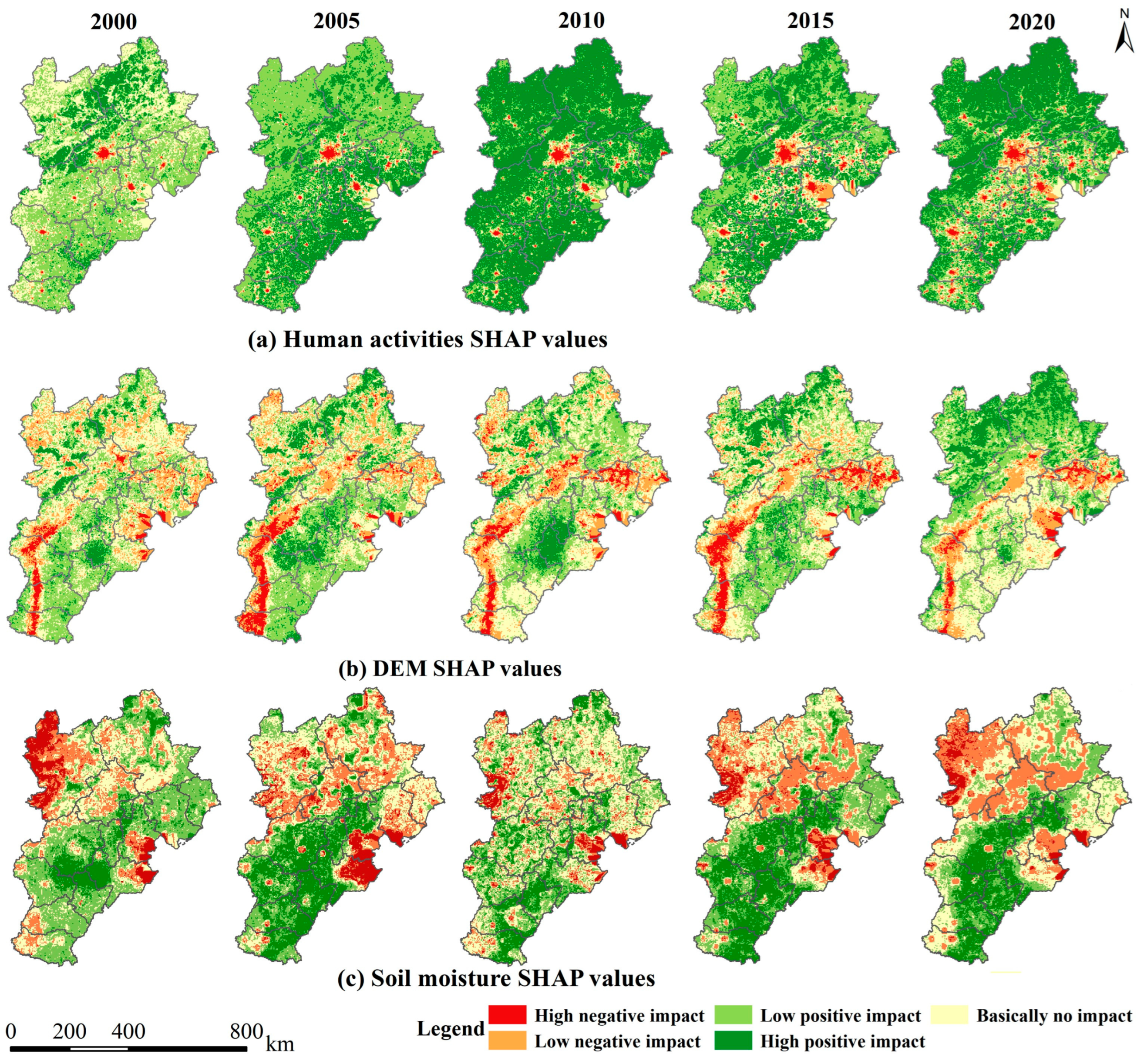

3.4. Spatial Variation of NDVI Influencing Factors

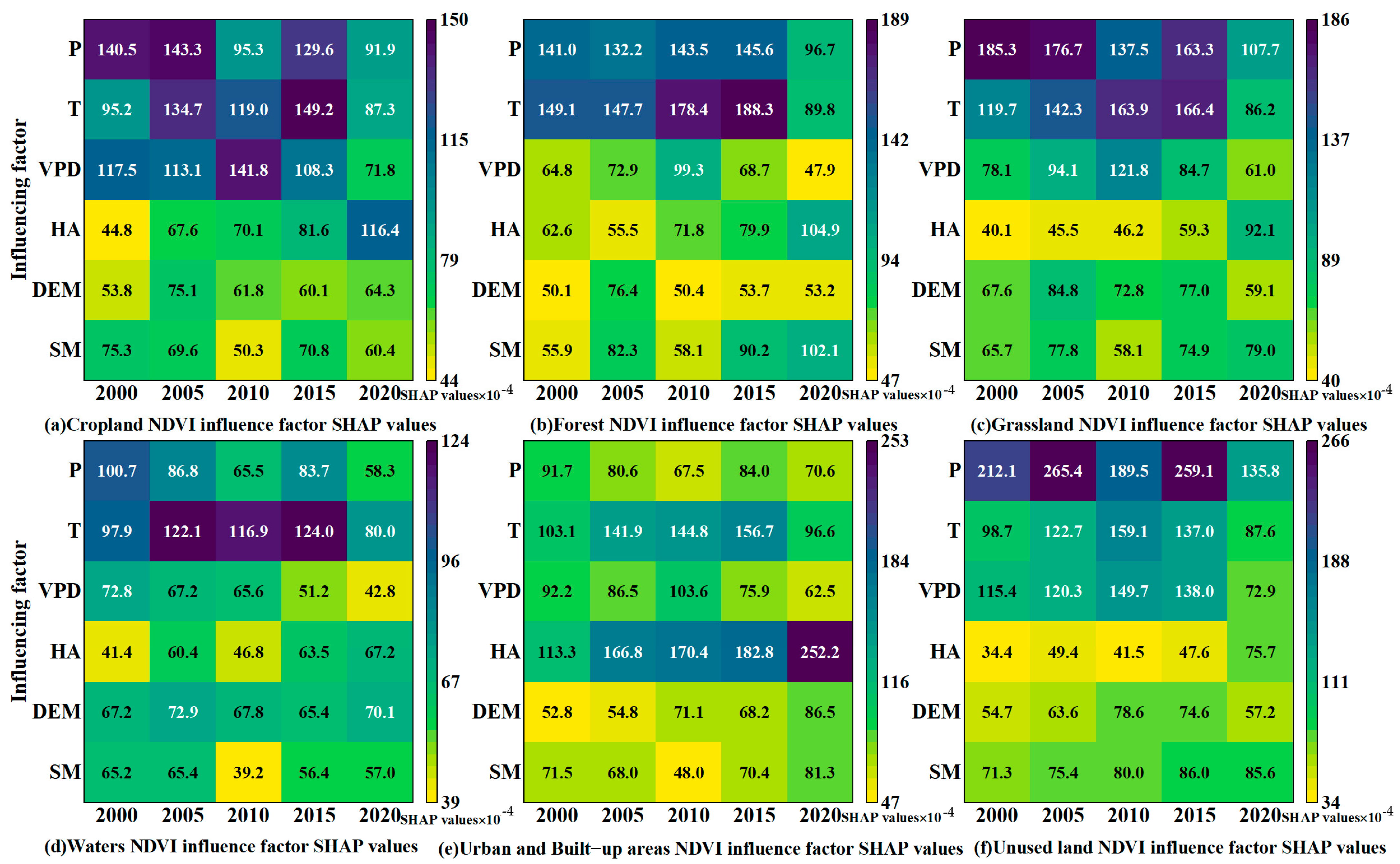

3.5. Influencing Factor Change Analysis of the NDVI for Different Land Use Types

4. Discussion

4.1. Change Trend and Influencing Factors of NDVI

4.2. Uniqueness and Uncertainty of the XGBoost-SHAP Method

4.3. The Positive Influence of Human Activities

4.4. Policy Implications

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- From 2000 to 2020, vegetation cover in the BTH region increased overall. The primary factors of vegetation change were precipitation, temperature, and HA, with precipitation and temperature alternately dominating in different years. However, HA became the primary factor in 2020. Although anthropogenic impacts were less significant than climatic factors overall, their negative influence on NDVI gradually intensified over time.

- (2)

- Regional variations in the impacts of temperature, precipitation, and HA on NDVI were evident. Most vegetation greening occurred in forest and grassland areas within the northwestern hilly region, where temperature was the primary factor for forests, while precipitation primarily influenced grasslands. In contrast, vegetation browning was concentrated in the southeastern plains, particularly in urban and built-up areas and croplands. Here, precipitation dominated NDVI trends in croplands, whereas HA was the key driver in urban areas.

- (3)

- We employed the XGBoost-SHAP method for NDVI prediction, which achieved high accuracy (R2 > 0.96) and outperformed RF, SVM, and KNN. With robust data analysis capabilities, the method not only revealed the spatial heterogeneity of different influencing factors but also effectively tracked their temporal variations at different time points. It provided clearer insights into NDVI changes and their prediction factors. The study offered a novel methodological reference for in-depth understanding and analysis of the influence patterns of NDVI to climate change and HA.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Ouyang, Z.; Zheng, H.; Xiao, Y.; Polasky, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Rao, E.; et al. Improvements in ecosystem services from investments in natural capital. Science 2016, 352, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehmood, K.; Anees, S.A.; Rehman, A.; Pan, S.; Tariq, A.; Zubair, M.; Liu, Q.; Rabbi, F.; Khan, K.A.; Luo, M. Exploring spatiotemporal dynamics of ndvi and climate-driven responses in ecosystems: Insights for sustainable management and climate resilience. Ecol. Informatics 2024, 80, 102532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Ge, W.; Guo, J.; Liu, J. Satellite remote sensing of vegetation phenology: Progress, challenges, and opportunities. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 217, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, S.; Wang, X.; Lian, X.; He, Y.; Ciais, P.; Park, T.; Chen, C.; Myneni, R.B.; Nemani, R.R.; Bjerke, J.W. Characteristics, drivers and feedbacks of global greening. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, G.; Guan, T.; Jin, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Ma, T. The sensitivity of vegetation cover to climate change in multiple climatic zones using machine learning algorithms. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 124, 107443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Shi, X.; Fu, Y. Identifying vegetation restoration effectiveness and driving factors on different micro-topographic types of hilly loess plateau: From the perspective of ecological resilience. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 289, 112562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Sun, R.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C. Temporal-spatial analysis of vegetation coverage dynamics in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei metropolitan regions. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2017, 37, 7418–7426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Dong, G.; Jiang, X.; Nie, T.; Guo, X. Analysis of factors influencing spatiotemporal differentiation of the NDVI in the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River from 2000 to 2020. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 10, 1072430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, H.; Haghighi, A.T.; Klve, B.; Luoto, M. Remote sensing of vegetation trends: A review of methodological choices and sources of uncertainty. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2025, 37, 101500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sun, R.; Ni, Z. Identification of Natural and Anthropogenic Drivers of Vegetation Change in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Megacity Region. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelsey, K.C.; Pedersen, S.H.; Leffler, A.J.; Sexton, J.O.; Feng, M.; Welker, J.M. Winter snow and spring temperature have differential effects on vegetation phenology and productivity across arctic plant communities. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 1572–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, J.; Peng, W.; Tao, S. Spatio-temporal Changes of Vegetation NDVI and Its Topographic Response in the Upper Reaches of the Minjiang River from 2000 to 2020. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2022, 31, 1534–1547. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, C. Analysis of the Spatiotemporal Characteristics and Influencing Factors of the NDVI Based on the GEE Cloud Platform and Landsat Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, R.; Wu, J.; Tian, F.; Yang, J.; Han, X.; Chen, M.; Zhao, B.; Lin, J. Reversal of soil moisture constraint on vegetation growth in North China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 865, 161246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, Q.; Li, T.; Zhang, K. Dynamic Vegetation Responses to Climate and Land Use Changes over the Inner Mongolia Reach of the Yellow River Basin, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Q.; Hao, Y.; Xia, A.; Liu, W.; Hu, R.; Cui, X.; Xue, K.; Song, X.; Xu, C.; Ding, B.; et al. Quantitative Assessment of the Impact of Physical and Anthropogenic Factors on Vegetation Spatial-Temporal Variation in Northern Tibet. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Gao, P.; Tian, B.; Wu, C.; Mu, X. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of NDVI and Its Influencing Factors Based on the ESTARFM in the Loess Plateau of China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, F.; Niu, L.; Wang, Y. A study of the impacts of urban expansion on vegetation primary productivity levels in the Jing-Jin-Ji region, based on nighttime light data. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hu, C.; Dong, X.; Li, J. NDVI Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Typical Ecosystems in the Semi-Arid Region of Northern China: A Case Study of the Hulunbuir Grassland. Land 2023, 12, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yan, S.; Ciais, P.; Wigneron, J.P.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Fu, Z.; Ma, H.; Liang, Z.; Wei, F.; et al. Exploring complex water stress–gross primary production relationships: Impact of climatic drivers, main effects, and interactive effects. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 4110–4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Fan, M.; Chen, Y.; Gang, C.; You, Y.; Wang, Z. Dynamics of global dryland vegetation were more sensitive to soil moisture: Evidence from multiple vegetation indices. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 331, 109327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuoku, L.; Wu, Z.; Men, B. Impacts of climate factors and human activities on ndvi change in china. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, W.; Jing, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, M.; Ou, Y.; Lu, M.; Dou, S. Dynamic Variation of Vegetation Cover and Its Relation with Climate Variables in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. Bull. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 40, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Jiao, S.; An, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Mo, Y.; Shao, Y.; Feng, Y. Impacts of Climate Change and Human Activities on NDVI in Guizhou Province from 1998 to 2018. Resour. Environ. Yangtze Basin 2021, 30, 2883–2895. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, X.; Lei, Y.; Gao, S. The contributions of natural and anthropogenic factors to NDVI variations on the Loess Plateau in China during 2000–2020. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 143, 109342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Jia, Q.; Wang, P.; Zhang, J.; Hou, X.; Li, X.; Li, W. Analysis of spatial variability in factors contributing to vegetation restoration in Yan’an, China. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 113, 106278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hao, L.; Xu, Q.; Li, J.; Chang, H. Spatio-temporal variations of vegetation coverage and its geographical factors analysis on the Loess Plateau from 2001 to 2019. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2023, 43, 2397–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, X.; Christakos, G.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Gu, X.; Zheng, X. Geographical detectors-based health risk assessment and its application in the neural tube defects study of the Heshun Region, China. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Ma, M.; Liang, T.; Wu, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, W. Estimates of grassland biomass and turnover time on the Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 014020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Yuan, W.; Dong, W. A Machine Learning Method for Predicting Vegetation Indices in China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Jin, N.; Ma, X.; Wu, B.; He, Q.; Yue, C.; Yu, Q. Attribution of climate and human activities to vegetation change in China using machine learning techniques. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 294, 108146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anees, S.A.; Mehmood, K.; Rehman, A.; Rehman, N.U.; Muhammad, S.; Shahzad, F.; Hussain, K.; Luo, M.; Alarfaj, A.A.; Alharbi, A.A.; et al. Unveiling fractional vegetation cover dynamics: A spatiotemporal analysis using MODIS NDVI and machine learning. Environ. Sustain. Indic. 2024, 24, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Cao, S.; Bai, T.; Yang, Z.; Cai, Z.; Sun, W. Assessment of Vegetation Dynamics in Xinjiang Using NDVI Data and Machine Learning Models from 2000 to 2023. Sustainability 2025, 17, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.I. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 4768–4777. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, G.; Duan, K.; Liu, B.; Cai, X. Exploring the Individualized Effect of Climatic Drivers on MODIS Net Primary Productivity through an Explainable Machine Learning Framework. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhao, J.; Li, Y.; Lin, Y. Identifying trade-offs and synergies among land use functions using an XGBoost-SHAP model: A case study of Kunming, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 172, 113330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Fang, S. Exploring the coupling of ecosystem services and human well-being: Evidence from Chinese cities through interpretable machine learning. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 180, 114315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Liu, X.; Zhu, D.; Zhang, S. Unveiling multiscale and nonlinear effects of land use change drivers through interpretable machine learning model: Insights from “Ecological-cost and Economic-benefit” trade-off perspective. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 118, 108254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dikshit, A.; Pradhan, B. Interpretable and explainable AI (XAI) model for spatial drought prediction. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 801, 149797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Wan, G.; Qin, X. Decoding China’s new-type industrialization: Insights from an XGBoost-SHAP analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 478, 143927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wang, H.; Jiao, K. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of NDVI in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region based on MODIS Data and Quantitative Attribution. J. Geo-Inf. Sci. 2019, 21, 767–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; He, Y.; Song, C.; Pan, Y.; Qiu, T.; Tian, S. Disaggregating climatic and anthropogenic influences on vegetation changes in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 786, 147574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y. Pattern and change of NDVI and their environmental influencing factors for 1986–2019 in the Qinling-Daba Mountains of central China. Front. For. Glob. Change 2024, 7, 1372488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Ding, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, Z. 1km monthly temperature and precipitation dataset for China from 1901 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2019, 11, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNally, A. FLDAS Noah Land Surface Model L4 Global Monthly 0.1 × 0.1 Degree (MERRA-2 and CHIRPS). Goddard Earth Sciences Data and Information Services Center (GES DISC), v1. 2018. Available online: https://data.nasa.gov/dataset/fldas-noah-land-surface-model-l4-global-monthly-0-1-x-0-1-degree-merra-2-and-chirps-v001-f-af46e (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Howell, T.A.; Dusek, D.A. Comparison of vapor-pressure-deficit calculation methods—Southern high plains. J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 1995, 121, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhu, J.; Chen, N.; Jiang, Y.; Huang, K.; Zu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, G. Water availability is more important than temperature in driving the carbon fluxes of an alpine meadow on the Tibetan Plateau. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 256–257, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, B.; Yang, C.; Zhou, Y.; Yao, S.; Qian, X.; Wang, C.; Wu, B.; Wu, J. An extended time series (2000–2018) of global NPP-VIIRS-like nighttime light data from a cross-sensor calibration. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 889–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Tian, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Liu, J.; Ya, Q.; Li, Z. Spatio-Temporal Variation and Climatic Driving Factors of Vegetation Coverage in the Yellow River Basin from 2001 to 2020 Based on kNDVI. Forests 2023, 14, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waked, A.; Sauvage, S.; Borbon, A.; Gauduin, J.; Pallares, C.; Vagnot, M.P.; Léonardis, T.; Locoge, N. Multi-year levels and trends of non-methane hydrocarbon concentrations observed in ambient air in France. Atmos. Environ. 2016, 141, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. Xgboost: A scalable tree boosting system. In Proceedings of the 22nd Acm Sigkdd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, S.R.; Bakhit, P.R.; Ishak, S. An extreme gradient boosting method for identifying the factors contributing to crash/near-crash events: A naturalistic driving study. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 46, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrumbelj, E.; Kononenko, I. Explaining prediction models and individual predictions with feature contributions. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2014, 41, 647–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why should I trust you?” Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Shapley, L.S. A value for n-person games. Contributions to the Theory of Games II (1953) 307-317. In Classics in Game Theory; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M.; Li, Z.; Tian, X.; Chen, E.; Gu, C. Remote sensing estimation of gross primary productivity and its response to climate change in the upstream of Heihe River Basin. Chin. J. Plant Ecol. 2016, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Jia, J.; Liu, H.; Lin, Z. Relative importance of climate change and human activities for vegetation changes on China’s silk road economic belt over multiple timescales. Catena 2019, 180, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, K.; Gao, J.; Wu, S.; Hou, W. Research progress on the response processes of vegetation activity to climate change. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2018, 38, 2229–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhao, X.; Wu, D.; Tang, R.; Du, X.; Wang, H.; Zhao, J.; Xu, P.; Peng, Y. Impact of Urbanization and Climate on Vegetation Coverage in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region of China. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, T.; Xie, Z.; Wang, J. Vegetation Dynamics and Their Response to the Urbanization of the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region, China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Yin, Y.; Li, B. A New Scheme for Climate Regionalization in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2010, 65, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstadt, B.; Russell, C.; Wachter, S. Explaining Explanations in AI. In Proceedings of the Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, FAT* ’19, Atlanta, GA, USA, 29–31 January 2019; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, F.; Duan, P.; Yung Jim, C.; Weng Chan, N.; Shi, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, J.; Bahtebay, J.; Ma, X. Vegetation cover changes in China induced by ecological restoration-protection projects and land-use changes from 2000 to 2020. Catena 2022, 217, 106530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, B.; Jin, Y.; Qin, Z.; Ma, H.; Li, J.; Zhao, F.; Chen, S.; Zhu, X. Remote sensing monitoring of grassland vegetation growth in the Beijing–Tianjin sandstorm source project area from 2000 to 2010. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 51, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, X.; Yi, G.; Li, J.; Bie, X.; Hu, J. Quantitatively analyzing the driving factors of vegetation change in China: Climate change and human activities. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Factor | Spatial Resolution | Temporal Resolution | Data Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetation conditions (NDVI) | 250 m | 16 days | MODIS MOD13Q1 | |

| Climate conditions | ||||

| Precipitation(P) | 1000 m | monthly | National Earth System Science Data Center | |

| Temperature(T) | ||||

| Terrain (DEM) | 90 m | - | United States Geological Survey | |

| Hydrological and soil conditions | ||||

| Vapor pressure deficit (VPD) | 0.1° | monthly | Calculated from the formula | |

| Soil moisture content (SM) | 0–10 cm | FLDAS (Noah Land Surface Model L4) | ||

| 10–40 cm | ||||

| 40–100 cm | ||||

| 100–200 cm | ||||

| Clay area proportion (Clay) | 1000 m | - | Resource and Environment Science and Data Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences | |

| Changes in land use | ||||

| Cropland proportion (CROP) | 1000 m | 5 years | Resource and Environment Science and Data Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences | |

| Natural Vegetation area proportion (NV) | ||||

| Impervious surface area proportion (IS) | ||||

| Status of human activities | ||||

| Population density (POP) | 1000 m | 5 years | Resource and Environment Science and Data Center of Chinese Academy of Sciences | |

| Nighttime light (NTL) | 1000 m | yearly | An extended time-series (2000–2018) of global NPP-VIIRS-like nighttime light data | |

| Study Area and Land Use Type | Vegetation Change Trends | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely Significant Reduction | Significant Reduction | Non-Significant Reduction | Non-Significant Increase | Significant Increase | Extremely Significant Increase | |

| BTH region | 4.85 | 3.50 | 16.86 | 26.83 | 11.59 | 36.37 |

| cropland | 4.35 | 3.92 | 21.60 | 34.54 | 12.43 | 23.07 |

| Forest | 0.82 | 0.85 | 5.18 | 15.47 | 12.06 | 65.48 |

| Grassland | 1.03 | 1.03 | 6.33 | 19.40 | 12.61 | 59.22 |

| Water area | 5.33 | 3.98 | 17.70 | 23.74 | 7.29 | 14.25 |

| Urban and built-up areas | 17.87 | 8.83 | 29.06 | 23.98 | 5.93 | 11.17 |

| Unused land | 3.09 | 2.85 | 17.50 | 31.46 | 14.80 | 25.91 |

| Year | Model | (R2) | (MAE) | (RMSE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | KNN | 0.517 | 0.509 | 0.695 |

| SVR | 0.636 | 0.077 | 0.083 | |

| RF | 0.752 | 0.17 | 0.06 | |

| XGBoost | 0.961 | 0.019 | 0.026 | |

| 2005 | XGBoost | 0.969 | 0.018 | 0.026 |

| 2010 | 0.980 | 0.014 | 0.019 | |

| 2015 | 0.982 | 0.014 | 0.012 | |

| 2020 | 0.964 | 0.018 | 0.025 |

| Item | High Negative Impact | Low Negative Impact | Basically No Impact | Low Positive Impact | High Positive Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precipitation | <−0.092 | [−0.092, −0.041) | [−0.041, −0.005) | [−0.005, 0.015) | ≥0.015 |

| Temperature | <−0.039 | [−0.039, −0.018) | [−0.018, 0.006) | [0.006, 0.029) | ≥0.029 |

| VPD | <−0.023 | [−0.023, −0.008) | [−0.008, 0.007) | [0.007, 0.025) | ≥0.025 |

| HA | <−0.078 | [−0.078, −0.035) | [−0.035, −0.007) | [−0.007, 0.010) | ≥0.010 |

| DEM | <−0.029 | [−0.029, −0.014) | [−0.014, −0.004) | [−0.004, 0.007) | ≥0.007 |

| SM | <−0.031 | [−0.031, −0.015) | [−0.015, −0.002) | [−0.002, 0.012) | ≥0.012 |

| Year | Land Use Type | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cropland | Forest | Grassland | Water Area | Urban and Built-Up | Unused Land | |

| 2000 | 109.82 | 44.72 | 35.42 | 6.47 | 17.86 | 2.08 |

| 2005 | 108.42 | 44.85 | 35.20 | 6.30 | 19.57 | 2.02 |

| 2010 | 104.01 | 44.96 | 34.04 | 5.73 | 26.17 | 1.49 |

| 2015 | 102.51 | 44.83 | 33.82 | 5.68 | 28.16 | 1.41 |

| 2020 | 99.89 | 45.48 | 34.04 | 7.15 | 28.11 | 1.75 |

| Change amount | −9.94 | 0.77 | −1.38 | 0.68 | 10.24 | −0.33 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cao, Y.; Guo, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, A. Influencing Factor Analysis of Vegetation Spatio-Temporal Variability in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region Based on Interpretable Machine Learning. Forests 2025, 16, 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121873

Cao Y, Guo L, Wang H, Zhang A. Influencing Factor Analysis of Vegetation Spatio-Temporal Variability in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region Based on Interpretable Machine Learning. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121873

Chicago/Turabian StyleCao, Yuan, Lanxuan Guo, Hefeng Wang, and Anbing Zhang. 2025. "Influencing Factor Analysis of Vegetation Spatio-Temporal Variability in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region Based on Interpretable Machine Learning" Forests 16, no. 12: 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121873

APA StyleCao, Y., Guo, L., Wang, H., & Zhang, A. (2025). Influencing Factor Analysis of Vegetation Spatio-Temporal Variability in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region Based on Interpretable Machine Learning. Forests, 16(12), 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121873