Effect of Phosphorus Addition on Rhizosphere Soil Microbial Diversity and Function Varies with Tree Species in a Subtropical Evergreen Forest

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Phosphorus Addition Experiment

2.3. Soil Sampling

2.4. Soil Nutrient and Enzyme Measurement

2.5. Soil DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification, and Product Purification

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Soil Physicochemical Properties

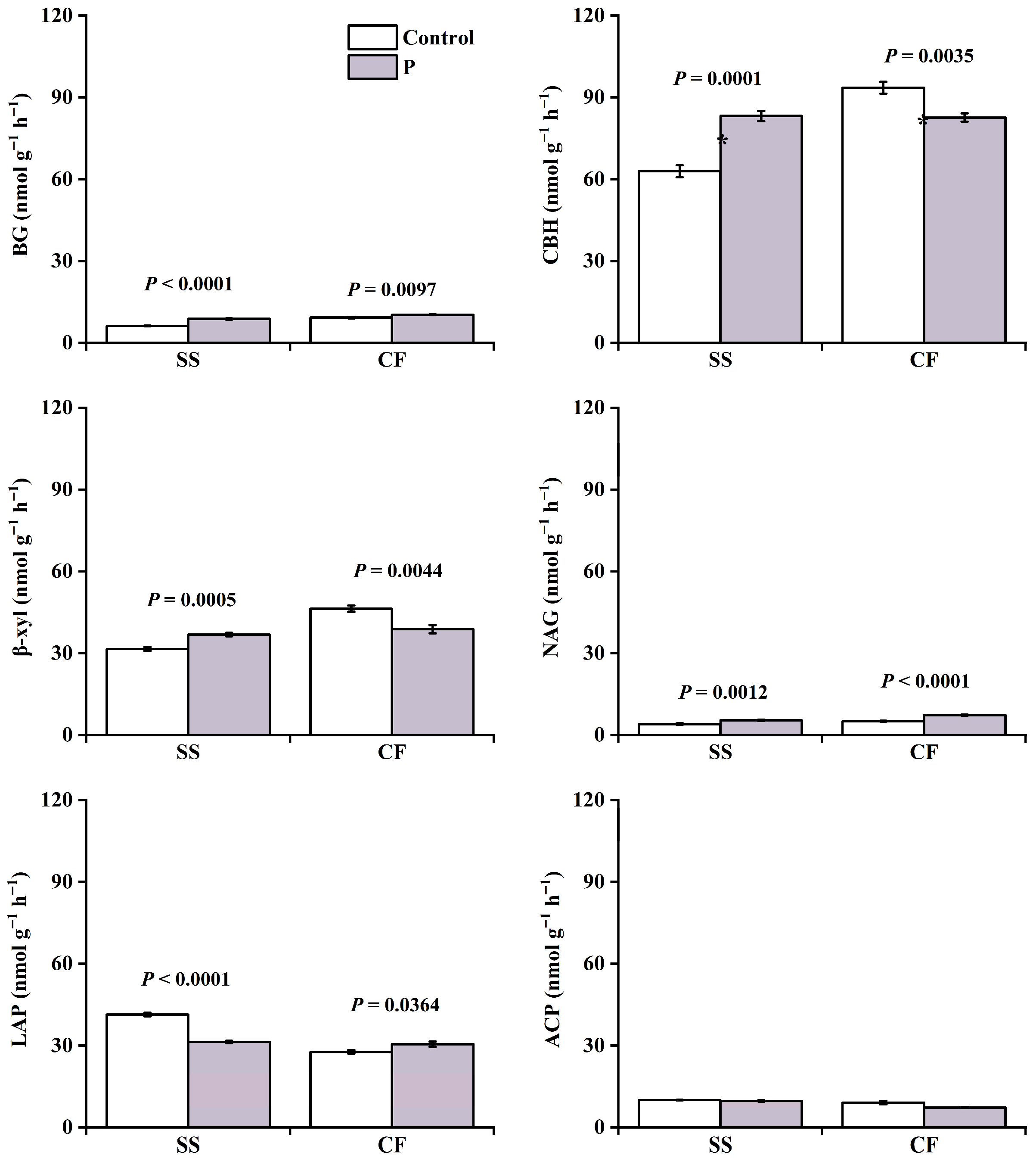

3.2. Soil Enzyme Activities

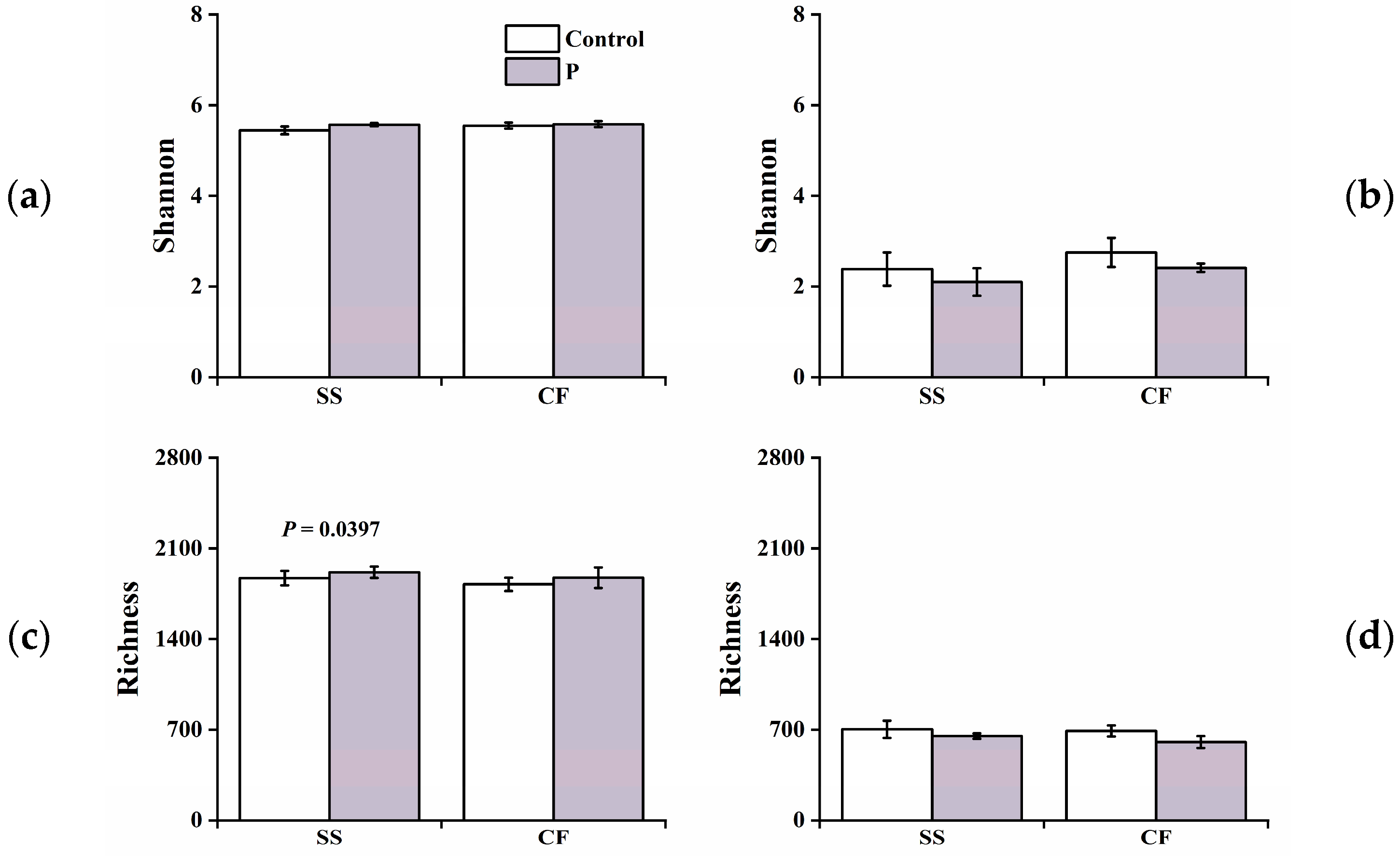

3.3. Microbial Diversity and Community Composition

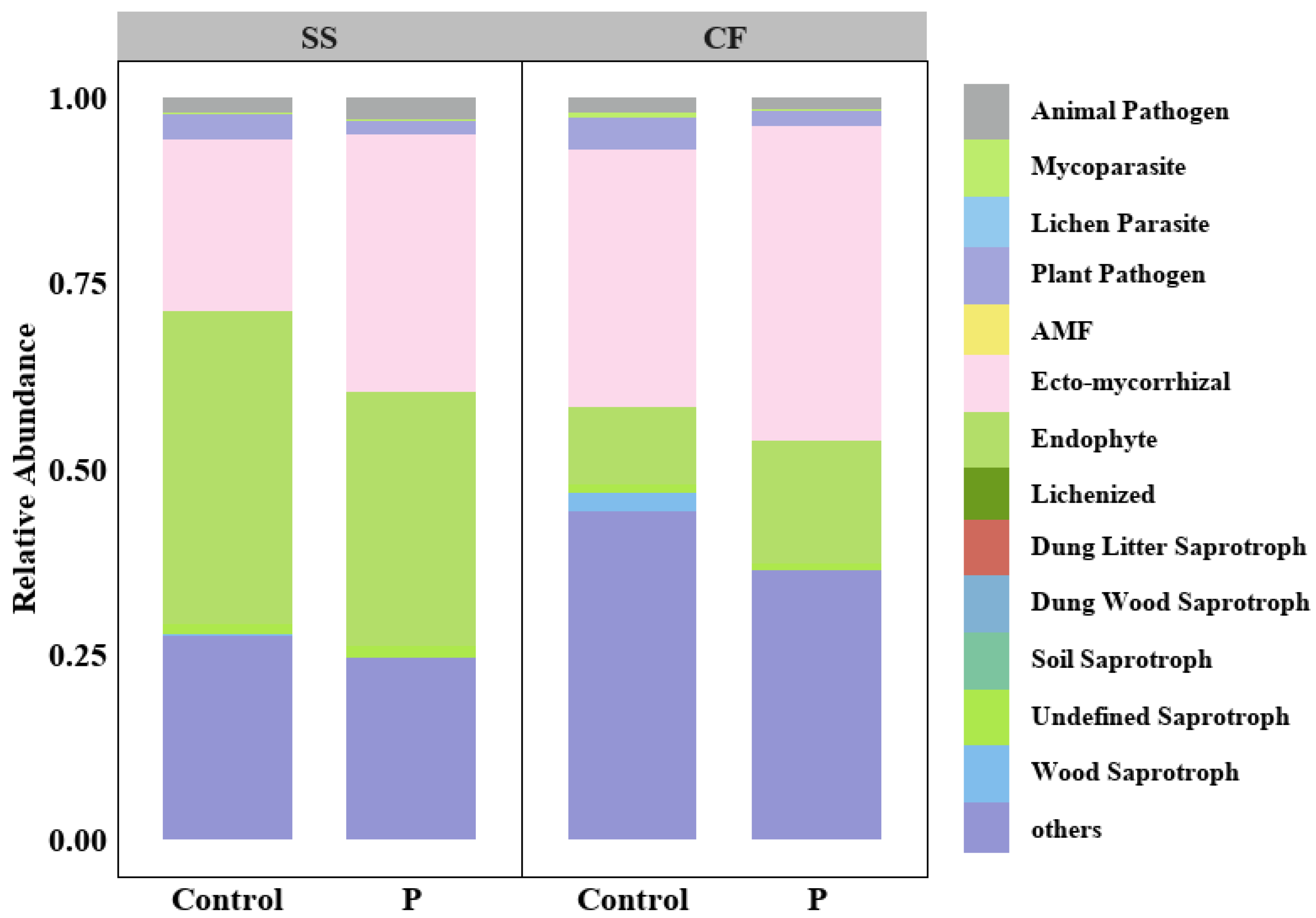

3.4. Fungal Trophic Group and Its Correlation with Microbial Diversity

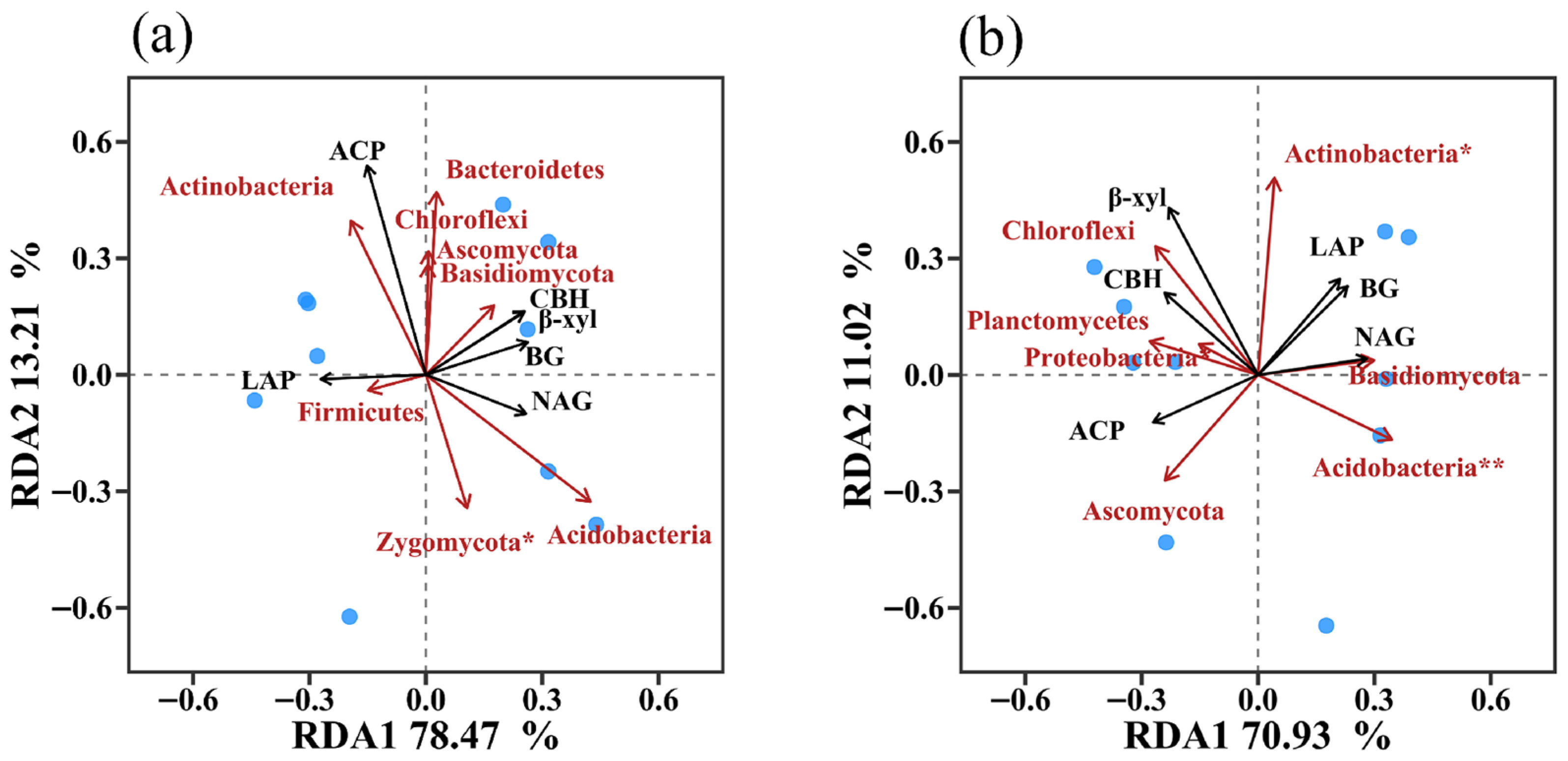

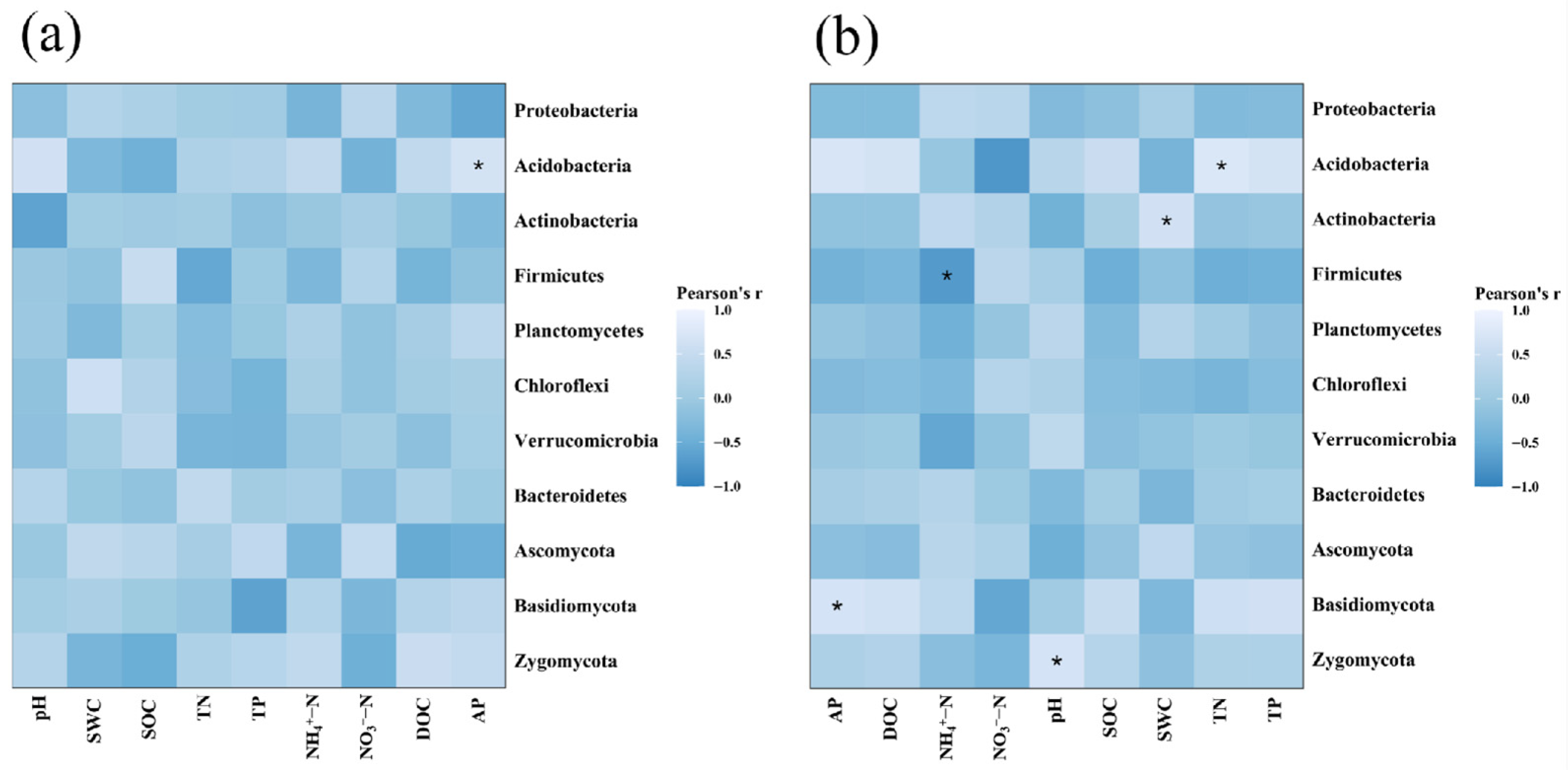

3.5. Relationships Between Soil Enzyme Activities, Microbial Community, and Physicochemical Properties

4. Discussion

4.1. Effects of P Addition on Microbial Community in Two Tree Species

4.2. Linkage Between Soil Ectoenzyme and Microbial Diversity Under P Enrichment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shen, J.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Bai, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, F. Phosphorus Dynamics: From Soil to Plant. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 997–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Li, S.; Zhu, B.; Homyak, P.; Chen, G.; Yao, X.; Wu, D.; Yang, Z.; Lyu, M.; Yang, Y. Long-term nitrogen deposition inhibits soil priming effects by enhancing phosphorus limitation in a subtropical forest. Glol. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 4081–4093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Ning, C.; Liu, T.; Yan, M.; Cai, W.; Xiao, J.; Yan, W. Impact of broadleaf tree introduction on rhizosphere fungal communities and root phosphorus-cycling genes in conifers of near-natural transformed plantations. For. Ecosyst. 2025, 14, 100378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.N.; Chen, X.X.; Liang, J.; Zhao, C.; Xiang, J.; Luo, L.; Wang, E.T.; Shi, F. Rhizocompartmental microbiomes of arrow bamboo (Fargesia nitida) and their relation to soil properties in Subalpine Coniferous Forests. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Wang, Y.; Bai, M.; Peng, T.; Li, H.; Xu, H.J.; Guo, G.; Bai, H.; Rong, N.; Sahu, S.K.; et al. Soil conditions and the plant microbiome boost the accumulation of monoterpenes in the fruit of Citrus reticulata ‘Chachi’. Microbiome 2023, 11, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, W.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Yang, Y.; Hu, Y. Rhizosphere Microbial Community and Metabolites of Susceptible and Resistant Tobacco Cultivars to Bacterial Wilt. J. Microbiol. 2023, 61, 389–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brundrett, M.C.; Tedersoo, L. Evolutionary history of mycorrhizal symbioses and global host plant diversity. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 1108–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, S.D. Mycorrhizal Fungi as Mediators of Soil Organic Matter Dynamics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2019, 50, 237–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; George, T.S.; Limpens, E.; Feng, G. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi conducting the hyphosphere bacterial orchestra. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadgil, R.L.; Gadgil, P.D. Mycorrhiza and Litter Decomposition. Nature 1971, 233, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.R.; Wan, J. Resource-ratio theory predicts mycorrhizal control of litter decomposition. New Phytol. 2019, 223, 1595–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Nie, C.; Liu, Y.; Du, W.; He, P. Soil microbial community composition closely associates with specific enzyme activities and soil carbon chemistry in a long-term nitrogen fertilized grassland. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 654, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xue, L.; Dong, Y.; Jiao, R. Effects of stand density on soil microbial community composition and enzyme activities in subtropical Cunninghamia lanceolate (Lamb.) Hook plantations. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 479, 118559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fierer, N.; Jackson, R.B.; Fierer, N.; Jackson, R.B. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, M.G.; Phillips, R.P. Spatio-temporal heterogeneity in extracellular enzyme activities tracks variation in saprotrophic fungal biomass in a temperate hardwood forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 138, 107600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrara, J.E.; Walter, C.A.; Hawkins, J.S.; Peterjohn, W.T.; Averill, C.; Brzostek, E.R. Interactions among plants, bacteria, and fungi reduce extracellular enzyme activities under long-term N fertilization. Glol. Change Biol. 2018, 24, 2721–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Qin, H.; Liang, C.; Shao, S.; Fuhrmann, J.J.; Chen, J.; Xu, Q. Moso bamboo invasion has contrasting effects on soil bacterial and fungal abundances, co-occurrence networks and their associations with enzyme activities in three broadleaved forests across subtropical China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 498, 119549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Hou, E.; Zhang, L.; Zang, X.; Yi, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wen, D. Effects of forest conversion on carbon-degrading enzyme activities in subtropical China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 696, 133968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Wang, Y.B.; Sui, J.H.; Liu, C.S.; Liu, R.; Xu, Z.F.; Han, X.Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Q.H.; Chen, C.B. Response of ginseng rhizosphere microbial communities and soil nutrients to phosphorus addition. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 226, 120687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Chen, X.; Su, H.; Xing, A.; Chen, G.; Zhu, J.; Zhu, B.; Fang, J. Phosphorus addition decreases soil fungal richness and alters fungal guilds in two tropical forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2022, 175, 108836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Fanin, N.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Y.; Du, G.; Hu, F.; Jiang, L.; Hu, S.; Liu, M. Nutrient-induced acidification modulates soil biodiversity-function relationships. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tian, D.; Wang, J.; Niu, S.; Kang, J.G. Differential mechanisms underlying responses of soil bacterial and fungal communities to nitrogen and phosphorus inputs in a subtropical forest. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, D.; Liang, G.; Qiu, Q.; Liu, J.; Zhou, G.; Liu, S.; Chu, G.; Yan, J. Effects of precipitation on soil organic carbon fractions in three subtropical forests in southern China. J. Plant Ecol. 2015, 9, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefroy, R.D.B.; Blair, G.J.; Strong, W.M. Changes in soil organic matter with cropping as measured by organic carbon fractions and 13C natural isotope abundance. Plant Soil 1993, 155, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, E.D.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. An extraction method for measuring soil microbial biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987, 19, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiya-Cork, K.R.; Sinsabaugh, R.L.; Zak, D.R. The effects of long term nitrogen deposition on extracellular enzyme activity in an Acer saccharum forest soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 1309–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, D.P.; Weintraub, M.N.; Grandy, A.S.; Lauber, C.L.; Rinkes, Z.L.; Allison, S.D. Optimization of hydrolytic and oxidative enzyme methods for ecosystem studies. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011, 43, 1387–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.H.; Song, Z.; Bates, S.T.; Branco, S.; Tedersoo, L.; Menke, J.; Schilling, J.S.; Kennedy, P.G. FUNGuild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.; Simko, V. R Package ‘Corrplot’: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix, version 0.95; SCIRP: Irvine, CA, USA, 2024.

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.; Blanchet, F.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.; O’Hara, R.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.; Szoecs, E.; et al. Vegan: Community Ecology Package, version 2.6-10; ScienceOpen: Lexington, MA, USA, 2025.

- Haq, I.U.; Hillmann, B.; Moran, M.; Willard, S.; Knights, D.; Fixen, K.R.; Schilling, J.S. Bacterial communities associated with wood rot fungi that use distinct decomposition mechanisms. ISME Commun. 2022, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, M.; Rewald, B.; Matthews, B.; Sandén, H.; Rosinger, C.; Katzensteiner, K.; Gorfer, M.; Berger, H.; Tallian, C.; Berger, T.W. Soil fertility relates to fungal-mediated decomposition and organic matter turnover in a temperate mountain forest. New Phytol. 2021, 231, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, Q.-C.; Jin, S.-S.; Lin, Y.; He, J.-Z.; Zheng, Y. Phosphorus addition predominantly influences the soil fungal community and functional guilds in a subtropical mountain forest. J. Sustain. Agric. Environ. 2024, 3, e12072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guhr, A.; Borken, W.; Spohn, M.; Matzner, E. Redistribution of soil water by a saprotrophic fungus enhances carbon mineralization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 14647–14651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballhausen, M.B.; Boer, W.D. The sapro-rhizosphere: Carbon flow from saprotrophic fungi into fungus-feeding bacteria. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 102, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Read, D.J.; Perez-Moreno, J. Mycorrhizas and nutrient cycling in ecosystems-a journey towards relevance? New Phytol. 2003, 157, 475–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Averill, C.; Bhatnagar, J.M.; Dietze, M.C.; Pearse, W.D.; Kivlin, S.N. Global imprint of mycorrhizal fungi on whole-plant nutrient economics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 23163–23168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, J.; George, T.S.; Feng, G. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi enhance mineralisation of organic phosphorus by carrying bacteria along their extraradical hyphae. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chaves, M.G.; Silva, G.G.Z.; Rossetto, R.; Edwards, R.A.; Tsai, S.M.; Navarrete, A.A. Acidobacteria Subgroups and Their Metabolic Potential for Carbon Degradation in Sugarcane Soil Amended with Vinasse and Nitrogen Fertilizers. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, B.D.; Tunlid, A. Ectomycorrhizal fungi—potential organic matter decomposers, yet not saprotrophs. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1443–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.W.; Kennedy, P.G.; Clemmensen, K. Melanization of mycorrhizal fungal necromass structures microbial decomposer communities. J. Ecol. 2018, 106, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellitier, P.T.; Zak, D.R. Ectomycorrhizal fungi and the enzymatic liberation of nitrogen from soil organic matter: Why evolutionary history matters. New Phytol. 2018, 217, 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fierer, N.; Bradford, M.A.; Jackson, R.B. Toward an ecological classification of soil bacteria. Ecology 2007, 88, 1354–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.B.; Martiny, A.C.; Martiny, J.B.H. Global biogeography of microbial nitrogen-cycling traits in soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 8033–8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konvalinková, T.; Püschel, D.; Řezáčová, V.; Gryndlerová, H.; Jansa, J. Carbon flow from plant to arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi is reduced under phosphorus fertilization. Plant Soil 2017, 419, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rineau, F.; Courty, P.-E. Secreted enzymatic activities of ectomycorrhizal fungi as a case study of functional diversity and functional redundancy. Ann. For. Sci. 2011, 68, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maron, P.A.; Sarr, A.; Kaisermann, A.; Lévêque, J.; Mathieu, O.; Guigue, J.; Karimi, B.; Bernard, L.; Dequiedt, S.; Terrat, S.; et al. High Microbial Diversity Promotes Soil Ecosystem Functioning. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e02738-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ma, K.; Lu, C.; Fu, Q.; Qiu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Schadt, C.W.; Chen, H. Functional Redundancy in Soil Microbial Community Based on Metagenomics Across the Globe. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 878978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitch, A.A.; Lang, A.K.; Whalen, E.D.; Helmers, E.M.; Goldsmith, S.G.; Hicks Pries, C. Mycorrhiza Better Predict Soil Fungal Community Composition and Function than Aboveground Traits in Temperate Forest Ecosystems. Ecosystems 2023, 26, 1411–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouwen, O.; Rineau, F.; Kohout, P.; Baldrian, P.; Eisenhauer, N.; Beenaerts, N.; Thijs, S.; Vangronsveld, J.; Soudzilovskaia, N.A. Towards understanding the impact of mycorrhizal fungal environments on the functioning of terrestrial ecosystems. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2025, 101, fiaf062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Berg, B.; Gu, W.; Wang, Z.; Sun, T. Effects of different forms of nitrogen addition on microbial extracellular enzyme activity in temperate grassland soil. Ecol. Process. 2022, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, H.; Zu, Y. Differences in the Activities of Eight Enzymes from Ten Soil Fungi and Their Possible Influences on the Surface Structure, Functional Groups, and Element Composition of Soil Colloids. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e111740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Lu, M.; Sun, X.; Luo, Z.; Zhao, J.; Fan, M. Effects of partial substitution of chemical fertilizer with organic manure on the activity of enzyme and soil bacterial communities in the mountain red soil. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1234904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keane, J.B.; Hoosbeek, M.R.; Taylor, C.R.; Miglietta, F.; Phoenix, G.K.; Hartley, I.P. Soil C, N and P cycling enzyme responses to nutrient limitation under elevated CO2. Biogeochemistry 2020, 151, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeds, J.A.; Marty Kranabetter, J.; Zigg, I.; Dunn, D.; Miros, F.; Shipley, P.; Jones, M.D. Phosphorus deficiencies invoke optimal allocation of exoenzymes by ectomycorrhizas. ISME J. 2021, 15, 1478–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| pH | SWC (%) | SOC (g kg−1) | TN (g kg−1) | TP (g kg−1) | -N (mg kg−1) | -N (mg kg−1) | DOC (mg kg−1) | AP (mg kg−1) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schima superba | Control | 4.61 (0.07) | 40.65 (2.65) | 87.38 (1.65) | 4.91 (0.06) | 0.80 (0.02) | 47.41 (0.78) | 51.93 (0.73) | 34.14 (0.48) | 4.08 (0.11) |

| P addition | 5.08 (0.14) | 41.58 (3.11) | 78.36 (0.76) | 5.18 (0.05) | 0.81 (0.01) | 68.82 (0.98) | 38.21 (0.91) | 39.25 (0.39) | 5.2 (0.04) | |

| p value | 0.020 | 0.825 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.813 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Castanopsis fargesii | Control | 4.61 (0.05) | 43.25 (2.88) | 72.56 (1.06) | 3.94 (0.06) | 0.62 (0.01) | 54.18 (1.28) | 45.61 (0.25) | 30.56 (0.78) | 4.35 (0.07) |

| P addition | 4.63 (0.12) | 42.9 (0.63) | 89.38 (1.13) | 4.9 (0.08) | 0.79 (0.01) | 56.36 (0.73) | 39.79 (0.93) | 36.39 (0.29) | 5.26 (0.08) | |

| p value | 0.881 | 0.907 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.179 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Taxon | Phylum | Schima superba | Castanopsis fargesii | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | P-Addition | Control | P-Addition | ||

| Bacteria | Proteobacteria | 0.399 (0.032) | 0.348 (0.023) | 0.435 (0.040) | 0.403 (0.012) |

| Acidobacteria | 0.229 (0.022) | 0.291 (0.031) | 0.203 (0.024) | 0.272 (0.019) | |

| Actinobacteria | 0.187 (0.015) | 0.178 (0.023) | 0.168 (0.020) | 0.174 (0.018) | |

| Firmicutes | 0.039 (0.009) | 0.031 (0.002) | 0.050 (0.015) | 0.026 (0.002) | |

| Planctomycetes | 0.036 (0.009) | 0.041 (0.005) | 0.037 (0.010) | 0.034 (0.005) | |

| Chloroflexi | 0.036 (0.004) | 0.038 (0.007) | 0.039 (0.014) | 0.025 (0.004) | |

| Verrucomicrobia | 0.043 (0.009) | 0.040 (0.007) | 0.034 (0.007) | 0.031 (0.004) | |

| Bacteroidetes | 0.013 (0.003) | 0.015 (0.003) | 0.014 (0.006) | 0.014 (0.002) | |

| Fungi | Ascomycota | 0.288 (0.054) | 0.114 (0.031) | 0.237 (0.045) | 0.217 (0.085) |

| Basidiomycota | 0.421 (0.137) | 0.504 (0.095) | 0.393 (0.123) | 0.551 (0.090) | |

| Zygomycota | 0.157 (0.084) | 0.343 (0.096) | 0.104 (0.042) | 0.164 (0.067) | |

| BG | CBH | β-xyl | NAG | LAP | ACP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schima superba | Bacteria | Shannon | 0.474 | 0.580 | 0.454 | 0.712 | −0.556 | −0.417 |

| Richness | 0.296 | 0.321 | 0.287 | 0.376 | −0.374 | −0.428 | ||

| Fungi | Shannon | −0.091 | −0.063 | −0.502 | −0.185 | 0.177 | 0.165 | |

| Richness | −0.204 | −0.243 | −0.516 | −0.101 | 0.211 | −0.201 | ||

| Castanopsis fargesii | Bacteria | Shannon | −0.372 | −0.397 | −0.327 | 0.121 | 0.151 | 0.234 |

| Richness | −0.282 | −0.184 | −0.134 | 0.167 | 0.480 | 0.108 | ||

| Fungi | Shannon | −0.260 | −0.125 | 0.031 | −0.341 | −0.542 | 0.217 | |

| Richness | −0.587 | 0.075 | 0.406 | −0.355 | 0.009 | 0.516 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, B.; Chen, F.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Huang, J.; Li, J.; Hu, X.; Zu, K.; Wang, H.; Wang, F. Effect of Phosphorus Addition on Rhizosphere Soil Microbial Diversity and Function Varies with Tree Species in a Subtropical Evergreen Forest. Forests 2025, 16, 1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121832

Xu B, Chen F, Wang X, Wang S, Huang J, Li J, Hu X, Zu K, Wang H, Wang F. Effect of Phosphorus Addition on Rhizosphere Soil Microbial Diversity and Function Varies with Tree Species in a Subtropical Evergreen Forest. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121832

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Bingshi, Fusheng Chen, Xiaodong Wang, Shengnan Wang, Junjie Huang, Jianjun Li, Xiaofei Hu, Kuiling Zu, Huimin Wang, and Fangchao Wang. 2025. "Effect of Phosphorus Addition on Rhizosphere Soil Microbial Diversity and Function Varies with Tree Species in a Subtropical Evergreen Forest" Forests 16, no. 12: 1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121832

APA StyleXu, B., Chen, F., Wang, X., Wang, S., Huang, J., Li, J., Hu, X., Zu, K., Wang, H., & Wang, F. (2025). Effect of Phosphorus Addition on Rhizosphere Soil Microbial Diversity and Function Varies with Tree Species in a Subtropical Evergreen Forest. Forests, 16(12), 1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121832