4.1. Comparison of Attention Mechanisms

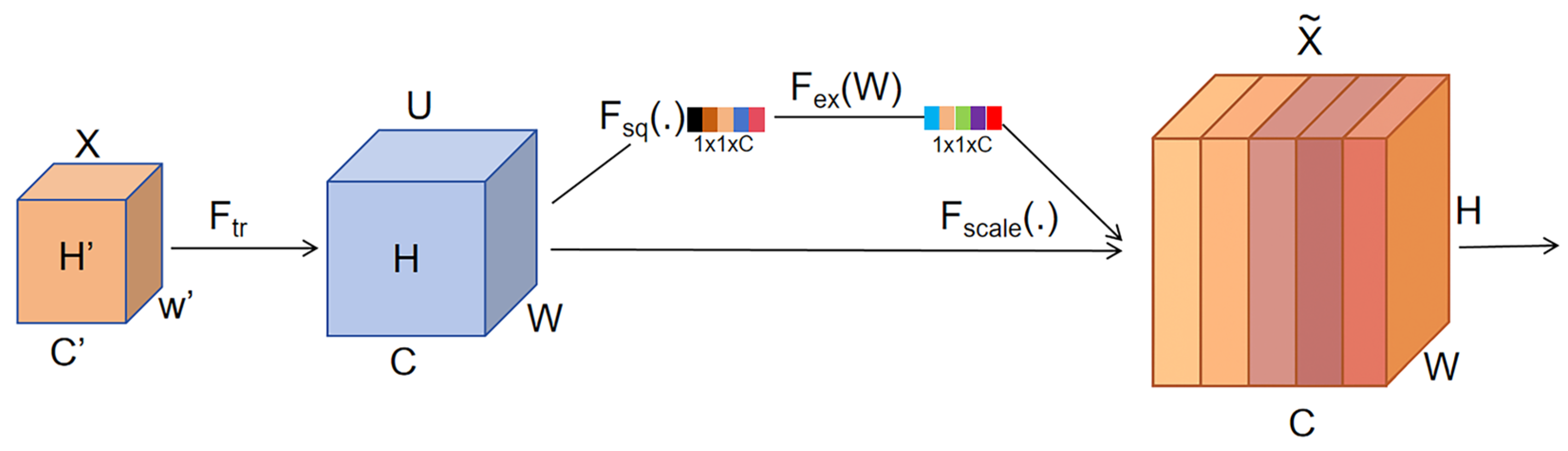

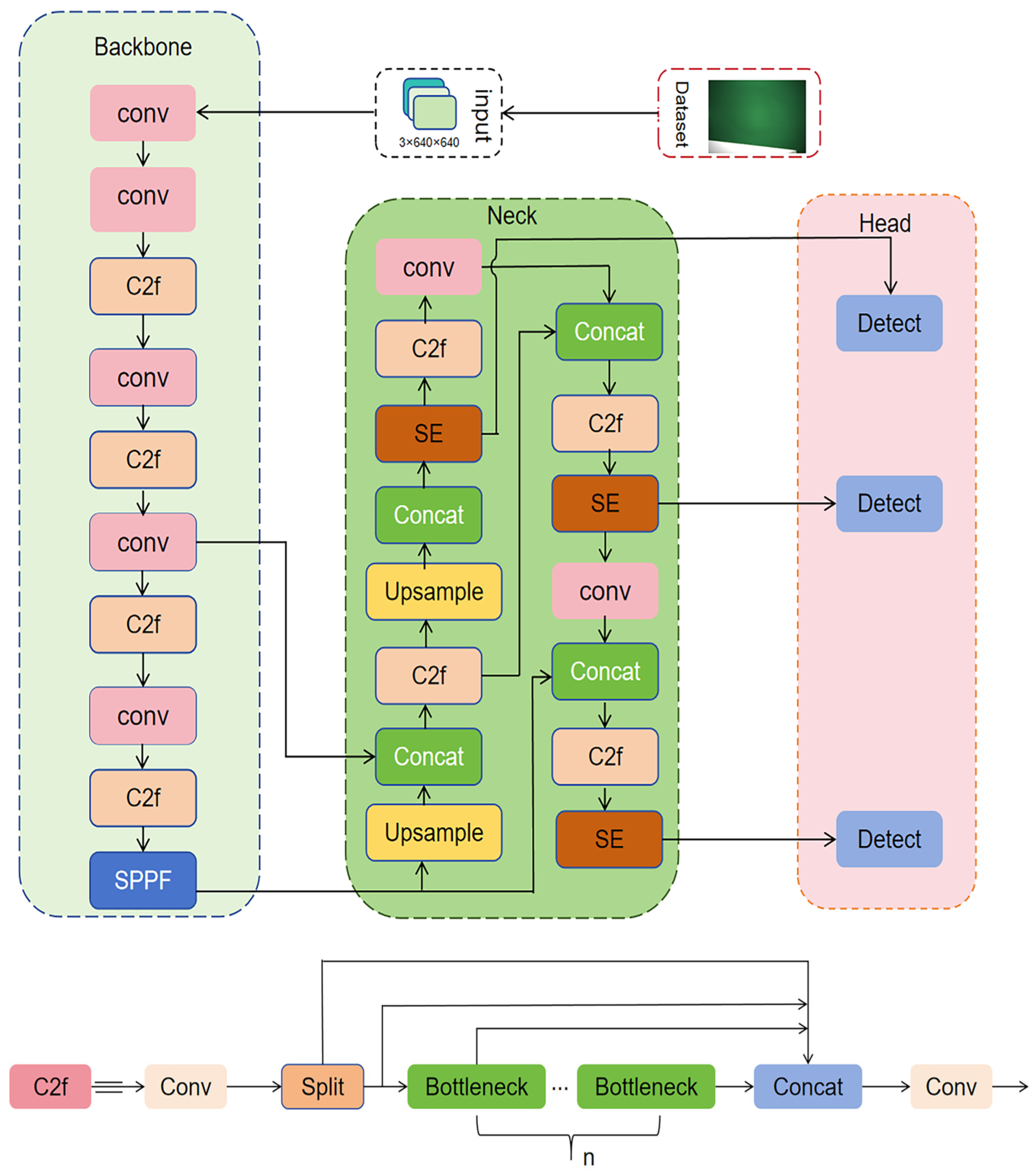

To investigate the impact of different attention mechanisms on detection performance, four mainstream attention modules—SE, CBAM, CA, and Shuffle—were integrated into the YOLOv8n model separately, while keeping the rest of the network architecture unchanged. The detection performance of these variants was then compared using the same dataset. The comparative results are summarized in

Table 4.

As summarized in

Table 4, all four attention modules improve detection to varying degrees, confirming that attention helps highlight subtle defects under low-contrast, texture-rich backgrounds. Compared with the baseline YOLOv8n (P = 93.2%, R = 94.2%, mAP@0.5 = 92.8%, mAP@[0.5:0.95] = 39.1%), SE provides the most balanced gains, increasing P and R to 94.3% (+1.1%) and 94.3% (+0.1%), and raising mAP@0.5 to 93.5% (+0.7%). CBAM and Shuffle Attention also yield stable improvements; CBAM achieves the best strict metric mAP@[0.5:0.95] of 39.9% (+0.8%), whereas Shuffle Attention slightly improves mAP@0.5 to 93.8% and mAP@[0.5:0.95] to 39.5%.

From a modeling perspective, these behaviors are consistent with the design of the modules and the characteristics of our defects. SE performs lightweight channel-wise re-weighting based on global pooling, which has been reported to enhance subtle object cues on complex backgrounds with very low computational overhead. For the tiny, low-contrast cracks, missing-print areas and spots embedded in halftone-dot textures, the most discriminative information is mainly encoded in a few weak channels rather than in stable spatial contours, so strengthening channel discriminability after multi-scale fusion is more effective than introducing complex spatial interactions. CBAM adds an extra spatial-attention branch that can further refine boundaries and thus slightly benefits the strict mAP@0.5:0.95, but this branch is more sensitive to local texture noise and increases the computational cost [

31]. Coordinate Attention injects directional positional cues into channel attention and is well suited for large objects with stable orientation; however, the defects in this work are mostly irregular and orientation-ambiguous, which limits its effectiveness [

32]. Shuffle Attention implements joint channel–spatial modeling via grouped shuffling operations, but in our experiments it brings only limited gains while slightly weakening the global channel dependency compared with SE [

33]. Overall, these results indicate that a lightweight channel re-calibration module such as SE is better matched to the representation characteristics of tiny printing defects and offers a more favorable accuracy–complexity trade-off than the other attention mechanisms.

4.2. Comparison of Loss Functions

To evaluate the performance improvement introduced by the EIoU loss function, the original CIoU loss in YOLOv8n was replaced with WIoU-V3, GIoU, and EIoU. Model performance metrics were then compared under a consistent experimental setup, as shown in

Table 5.

Table 5 shows consistent yet different levels of improvement when CIoU is replaced. Relative to the baseline CIoU (P = 93.2%, R = 94.2%, mAP@0.5 = 92.8%, mAP@[0.5:0.95] = 39.1%), WIoU-v3 yields mild gains (mAP@0.5 = 93.1%, mAP@[0.5:0.95] = 39.3%), and GIoU performs slightly better on the stricter metric (mAP@[0.5:0.95] = 39.5%). EIoU brings the most substantial and uniform improvement, increasing P to 94.1%, R to 95.0%, mAP@0.5 to 93.8%, and mAP@[0.5:0.95] to 39.6%.

From a geometric viewpoint, IoU-based losses such as DIoU/CIoU extend the original IoU by incorporating center-distance and aspect-ratio terms [

34], which improves localization but can still be sub-optimal for low-quality or highly elongated boxes—situations that frequently occur for thin cracks and small missing-print regions in printing inspection. WIoU and its variants (e.g., WIoU-v3 used in this work) introduce quality-aware re-weighting to stabilize regression for hard small targets [

35], but the overall gains on our dataset remain modest. In contrast, EIoU explicitly decomposes width and height errors and directly constrains side-length discrepancies, which better matches the small, thin and weakly bounded geometry of printing defects and explains its consistent improvements on both mAP@0.5 and mAP@[0.5:0.95].

4.3. Detection Results by Defect Type: Before and After Optimization

To further validate the detection capability of the proposed optimization strategy across different types of printed defects, three representative defect categories—cracks, missing prints, and spots—were selected. Precision and recall were compared between the original YOLOv8n model and the optimized YOLOv8n model, with the results presented in

Table 6.

As shown in

Table 6, the optimized YOLOv8n model achieved consistent improvements in detection performance across all defect categories:

For Cracks, the optimized model achieved a precision of 98.5% and a recall of 96.8%, representing a 2.6-percentage-point improvement in precision over the original model (95.9%, 96.5%). This indicates that the optimized model possesses stronger discriminative capability in modeling boundary details.

For missing print defects, the optimized model achieved a precision of 97.9% and a recall of 96.4%, showing higher consistency and detection stability compared to the original YOLOv8n model (95.0%, 96.3%). This demonstrates improved robustness when handling low-contrast targets.

For Spot defects, which are relatively more challenging, the optimized model still achieved a slight precision increase from 89.4% to 89.5% and an improvement in recall from 89.7% to 90.5%, indicating that the optimization strategy also has potential to enhance detection of small targets with low-texture contrast.

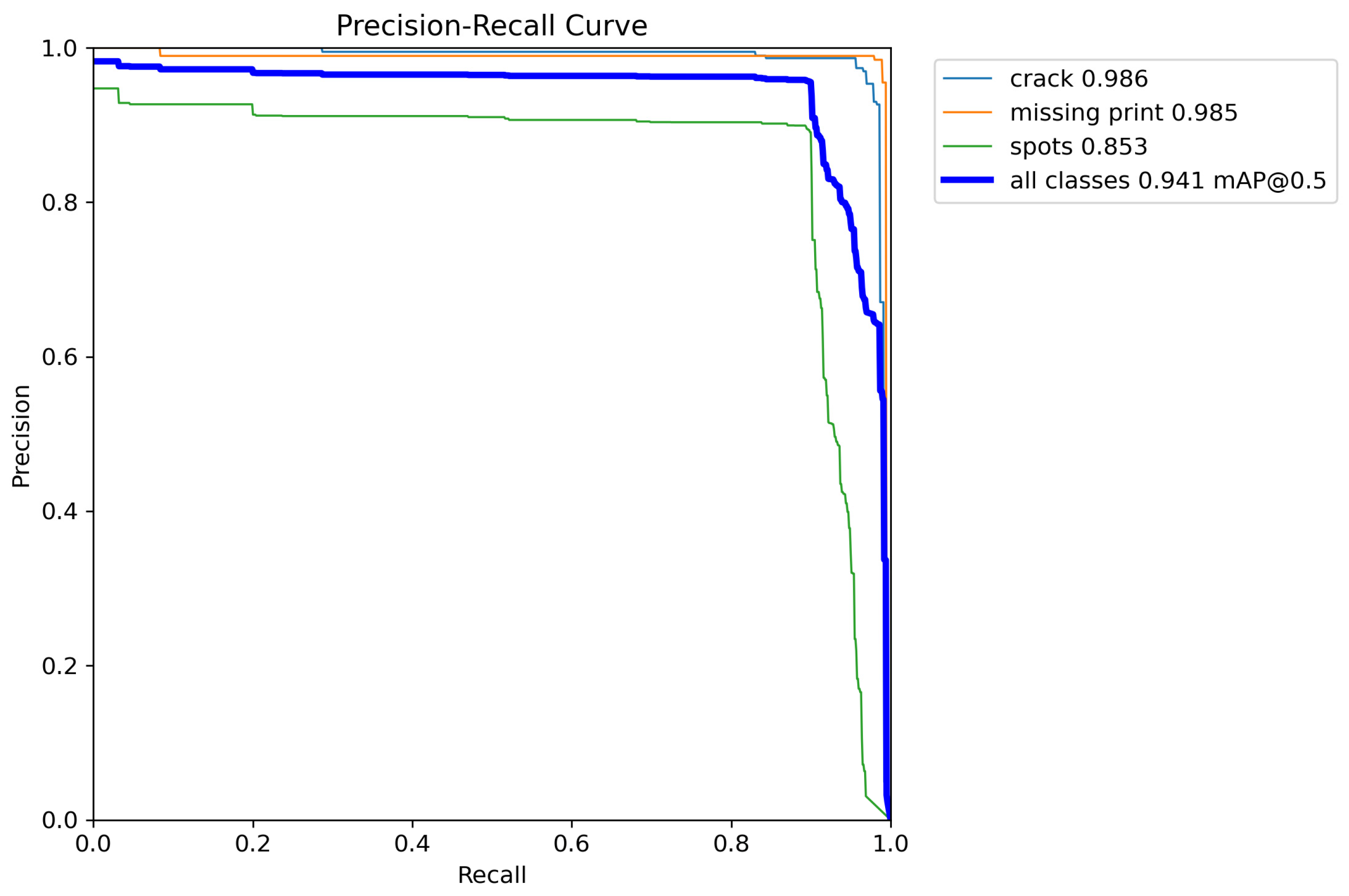

To further reveal class-specific performance, we report the per-class PR curves and AP values of the optimized model on the test set (

Figure 5). The AP@0.5 for cracks and missing prints is close to 0.99, whereas spots remain more challenging due to weak contrast and strong texture interference, leading to a relatively lower AP.

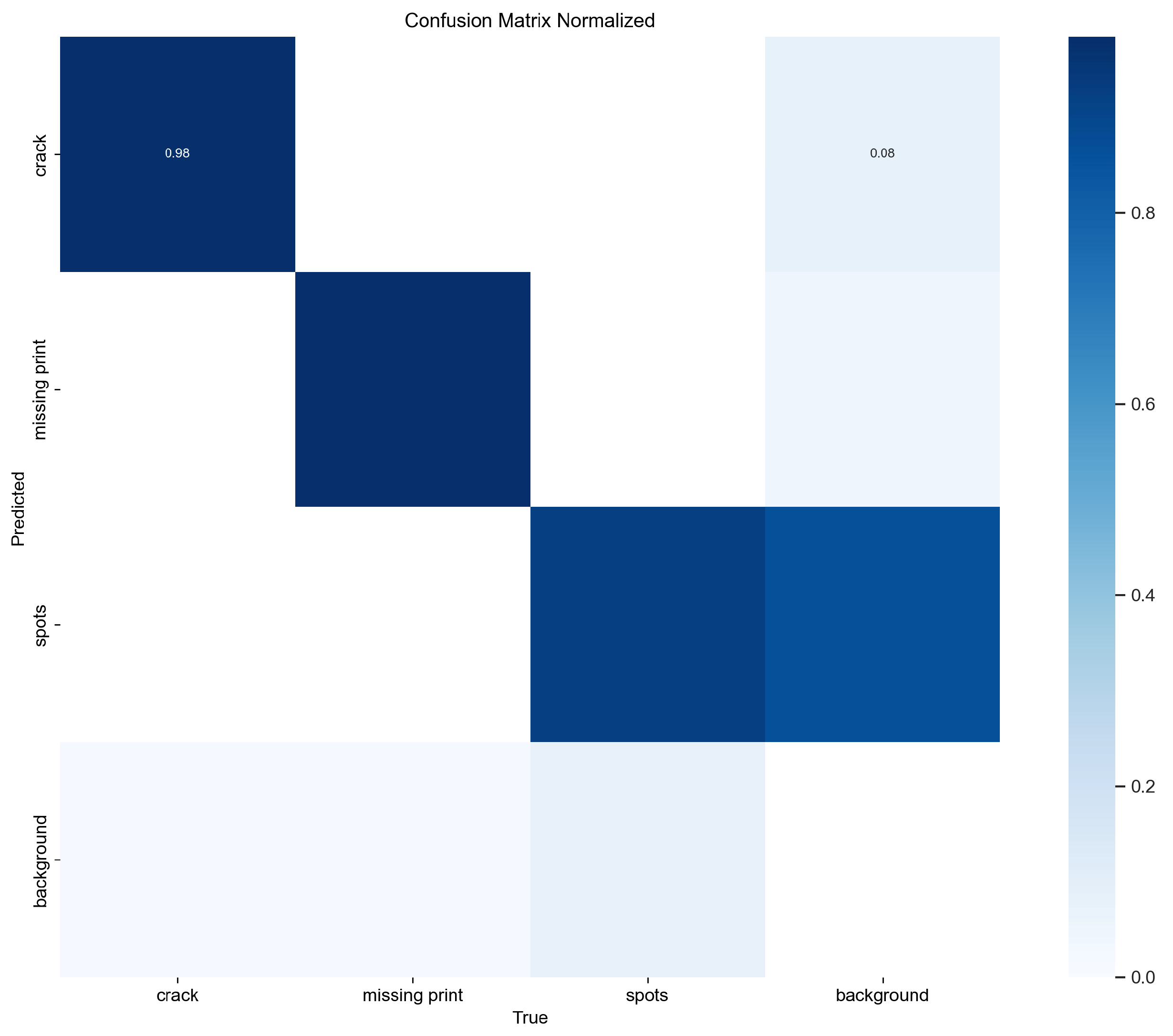

Figure 6 presents the normalized confusion matrix, which clarifies the major confusion patterns among defect categories. The dominant diagonal entries indicate reliable classification overall, and most residual errors arise from the confusion between tiny spot defects and background textures, consistent with their imaging characteristics.

4.4. Ablation Study

To evaluate the specific performance improvements contributed by the EIoU loss function and SE attention mechanism in the proposed optimization strategy, an ablation study was conducted. Based on the YOLOv8n model, three configurations were tested: incorporation of EIoU loss, integration of SE attention, and the combination of both. The impact of each configuration on detection accuracy was assessed. The experimental results are presented in

Table 7.

As shown in

Table 7, the original YOLOv8n model achieved P of 93.2%, R of 94.2%, and mAP@0.5 of 92.8%. After incorporating the EIoU loss function, the model’s bounding box regression capability was enhanced, with precision increasing to 94.1%, recall to 95.0%, and mAP@0.5 to 93.8%, indicating that EIoU positively optimizes object localization performance. Furthermore, introducing the SE attention mechanism also improved model performance, particularly in the comprehensive metric mAP@[0.5:0.95], which increased from 39.1% to 39.6%, demonstrating the effectiveness of the SE mechanism in enhancing channel feature representation.

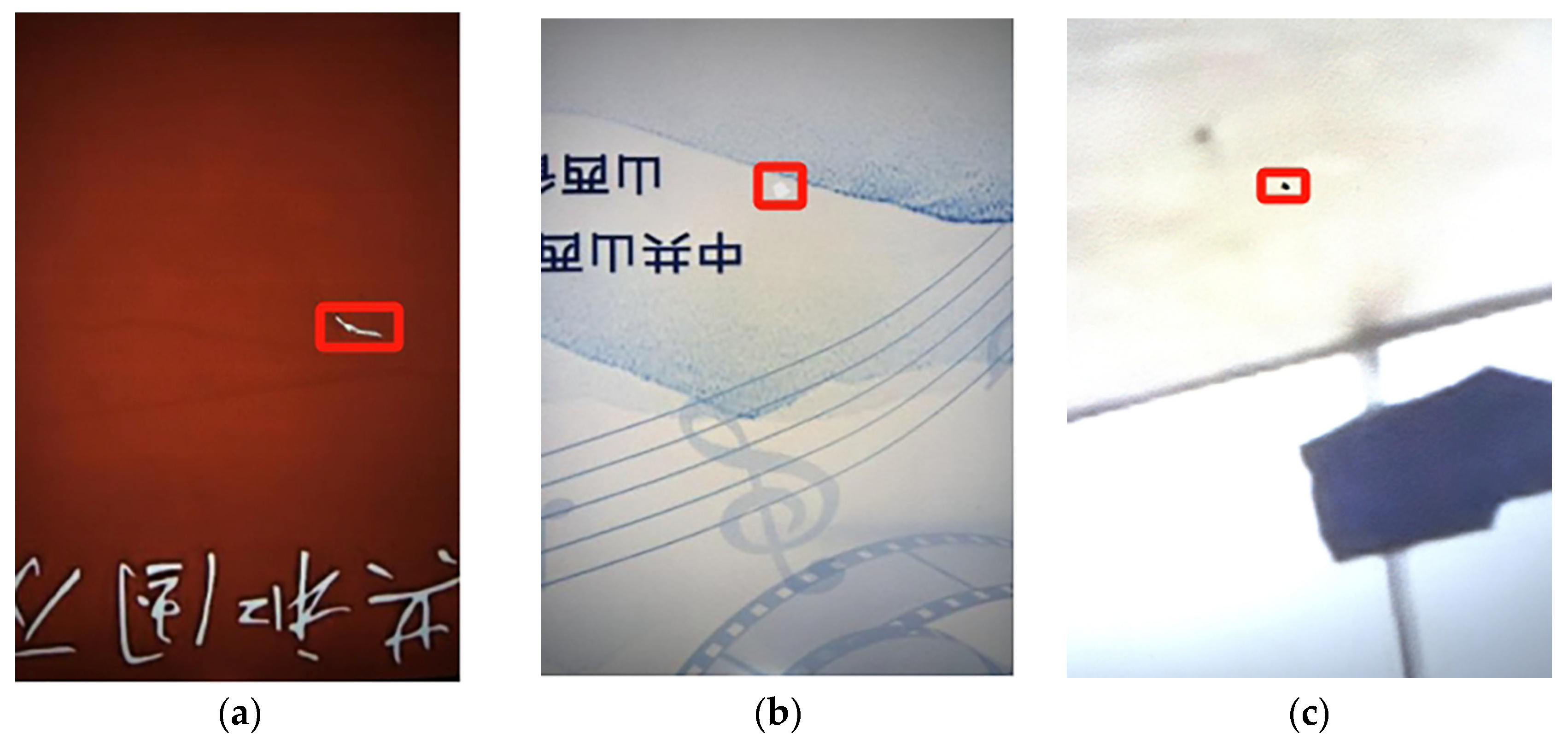

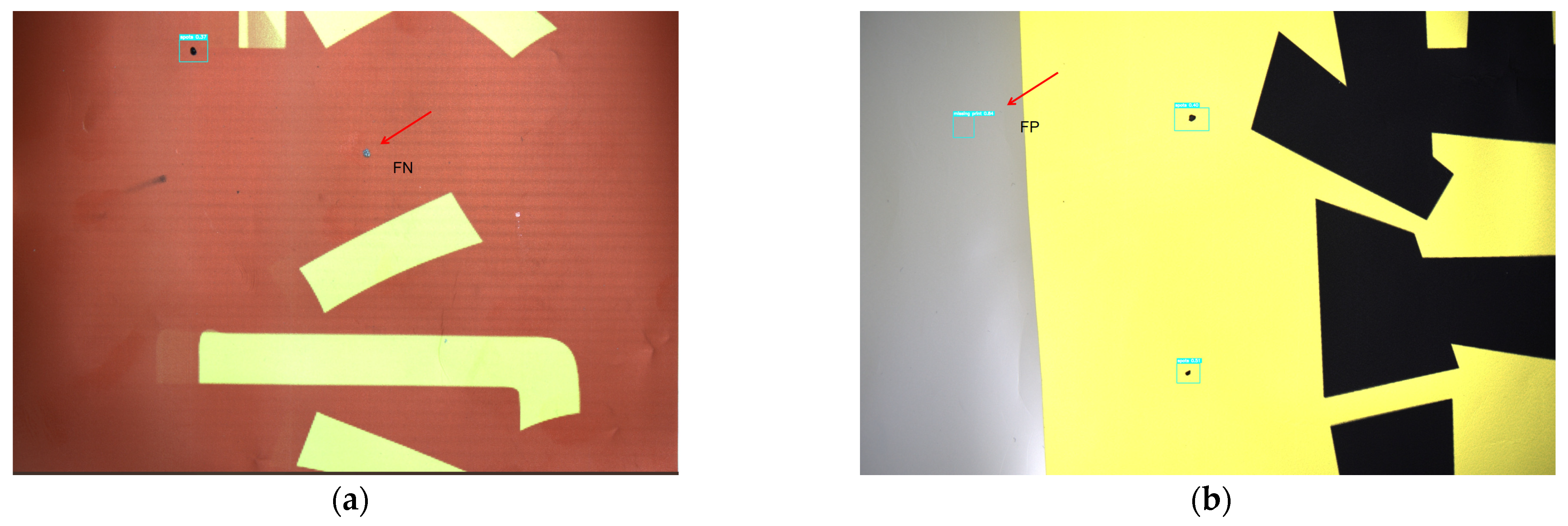

When EIoU and the SE mechanism were combined, the model achieved optimal overall performance, with precision reaching 95.1%, mAP@0.5 at 94.1%, and mAP@[0.5:0.95] at 39.6%. This confirms the synergistic effect of EIoU loss and SE attention, as they respectively enhance model performance in bounding box regression accuracy and channel feature responsiveness, exhibiting complementary benefits. Therefore, both the proposed EIoU and SE modules independently improved object detection performance, and their combined use produced more stable and significant enhancements, providing an effective pathway for subsequent model optimization. As shown in

Figure 7, the proposed method can detect various defects such as missing prints, cracks, and spots in printed materials, intuitively demonstrating the detection performance of the improved model on real samples.

4.5. Comparison with Other Models and Real-Time Performance Analysis

To further evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed optimization strategy in printing defect detection, this study conducted a comparative analysis with current mainstream object detection models, including YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv5s, YOLOv6s, YOLOv8s, and YOLOv8m. The analysis focused on comprehensive performance in terms of accuracy and efficiency, with the optimized YOLOv8n model included for evaluation. The experimental results are presented in

Table 8.

As shown in

Table 8, YOLOv3-tiny has an advantage in lightweight design (model size 23.2 MB, 18.9 GFLOPs), but its accuracy remains relatively low (mAP@0.5 = 92.4%), which is insufficient for high-precision industrial inspection requirements. YOLOv5s and YOLOv6s achieved a balance between model complexity and inference speed. Notably, YOLOv6s reached a maximum inference speed of 145.6 FPS with relatively low computation (11.8 GFLOPs), demonstrating strong real-time capability. However, its detection accuracy (mAP@0.5 = 92.1%) remained suboptimal.

Overall, the YOLOv8 series outperformed previous models in accuracy. YOLOv8m achieved an mAP@0.5 of 93.4%, but its computational cost and model size increased substantially (78.7 GFLOPs, 49.6 MB), limiting practical deployment. YOLOv8s reduced model size and computation to some extent, yet its inference speed offered no significant advantage.

In contrast, the proposed optimized YOLOv8n model achieved the best overall performance while remaining lightweight. The model contains only 3.02 M parameters, requires 8.1 GFLOPs, and has a size of 6 MB, yet exhibits significant accuracy improvements, achieving an mAP@0.5 of 94.1% and precision of 95.1%. Its inference speed reaches 100.2 FPS, meeting the dual requirements of real-time processing and high accuracy for high-speed printing production lines. In summary, the optimized YOLOv8n demonstrates advantages in detection accuracy, inference speed, and lightweight design, highlighting its strong potential for practical engineering applications.

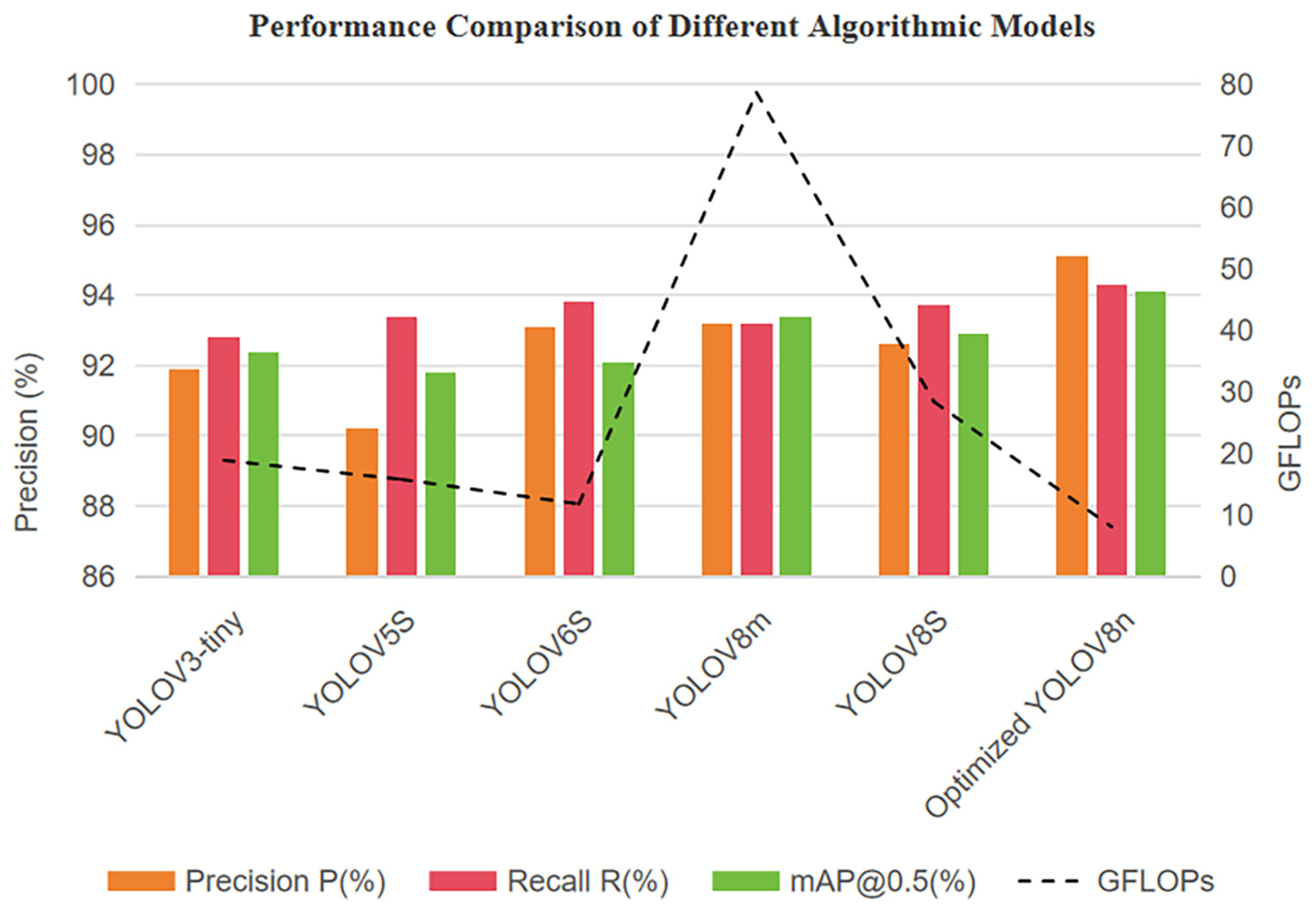

To visually illustrate the comprehensive advantages of the optimized YOLOv8n model in terms of accuracy, computational cost, and model size,

Figure 8 compares key detection metrics—precision (P), recall (R), and mAP@0.5—across mainstream models, overlaid with GFLOPs to depict computational complexity. As shown, the optimized YOLOv8n achieves excellent performance with only 8.1 GFLOPs and a 6 MB model size, reaching 95.1% precision, 94.3% recall, and 94.1% mAP@0.5, outperforming YOLOv3-tiny, YOLOv5s, YOLOv6s, and YOLOv8s. These results confirm the effectiveness of the proposed optimization strategy and its strong potential for industrial deployment.

As shown in

Figure 8, the improved YOLOv8n outperforms the comparison models in Precision, Recall, and mAP@0.5. Despite requiring only 8.1 GFLOPs of computation and 6 MB of storage, it still achieves an inference speed of 100.2 FPS, demonstrating an outstanding balance between accuracy and computational complexity. Based on these results, the following section discusses the engineering and industrial implications of the proposed method from the downstream production perspective of the “forest–wood–pulp–paper–printing” value chain, with a particular focus on wood-based manufacturing processes.

To clarify the practical meaning of the achieved inference speed (100.2 FPS), we quantitatively relate the processing rate to the throughput requirement of the roll-to-roll digital printing line from which the dataset was collected. Using a representative web speed of ≈ 50 m/min, the corresponding linear speed is v

s = 50/60 ≈ 0.833 m/s. With the measured inference rate, the interval between consecutive frames is Δt = 1/FPS ≈ 0.00998 s, yielding a per-frame covered web length of:

Equivalently, the spatial sampling density along the moving web is:

This mapping indicates that, at a typical operating speed, the proposed system performs dense continuous inspection (roughly one frame every 8 mm) without evident spatial gaps, providing sufficient real-time margin and throughput for online quality control.

Beyond sampling density, roll-to-roll online quality control requires the detection latency to satisfy control-loop constraints. Let the web speed be vs and the distance from the camera station to the downstream action unit (alarm/marking/rejection/stop) be d. The end-to-end latency should meet Le2e ≤ d/vs to ensure that defects can be acted upon before reaching the actuator. Under a representative speed of 50 m/min (vs ≈ 0.833 m/s) and a typical industrial camera–actuator distance on the order of 0.3–0.5 m, the allowable latency budget is about 0.36–0.60 s. The proposed model yields a single-frame inference interval of Δt ≈ 9.98 ms (100.2 FPS) on the target hardware, which is far below this threshold, demonstrating sufficient low-latency margin for roll-to-roll control.

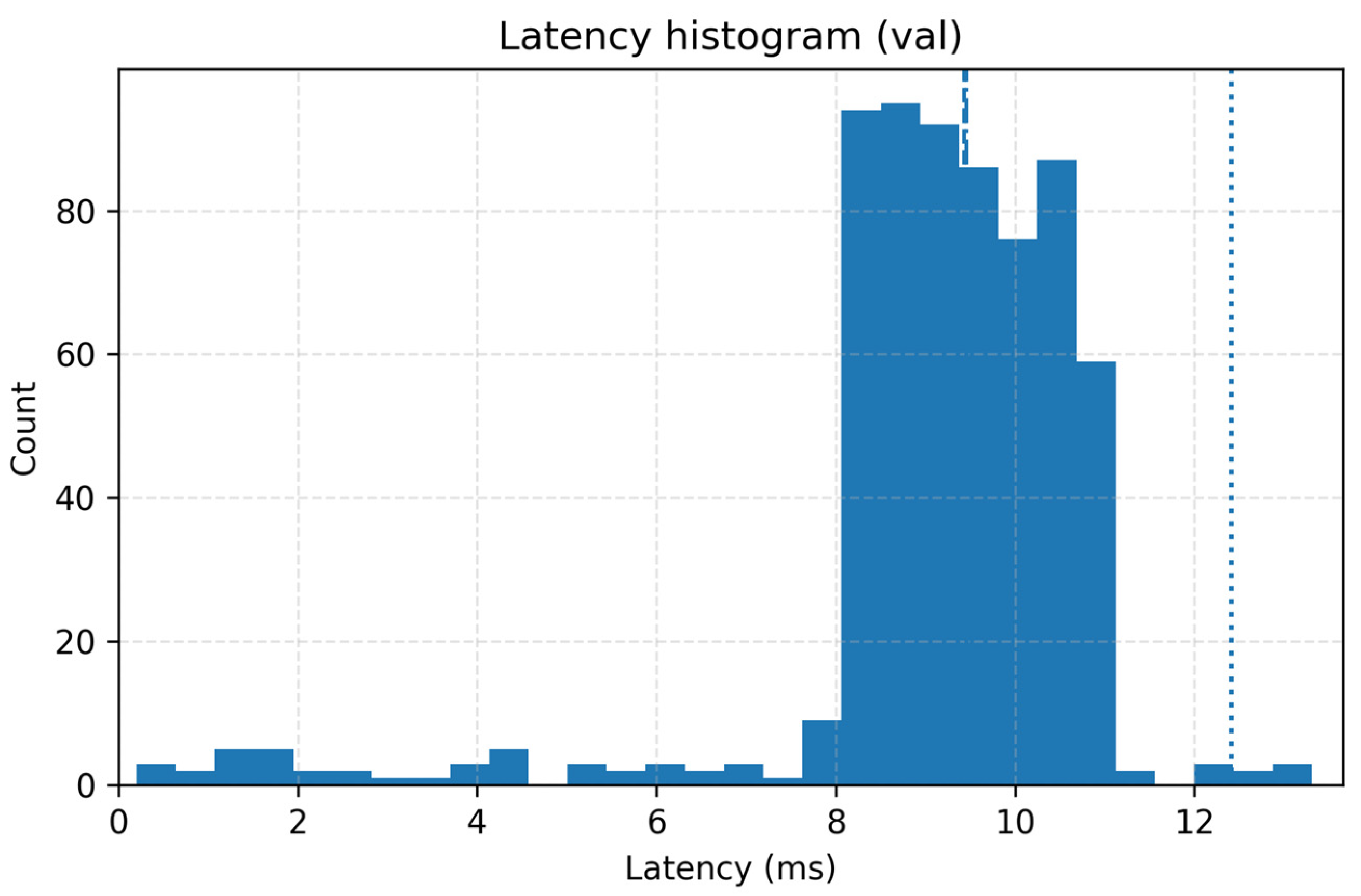

In addition, to assess the stability of real-time inference, we report the end-to-end per-frame latency distribution on the validation set, as shown in

Figure 9. Most frames are processed within approximately 8–11 ms, with an average latency of 9.83 ms, and p95 and p99 values of 10.94 ms and 11.80 ms, respectively, indicating no evident long-tail jitter. These results demonstrate that the improved YOLOv8n model provides stable low-latency performance under the current hardware and parameter configuration, which is consistent with the ≈100 FPS throughput analysis above and satisfies the real-time requirements of roll-to-roll online inspection.