From Laboratory Screening to Greenhouse Flight Bioassay: Development of a Plant-Based Attractant for Tomicus brevipilosus

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Test Insects

2.2. Experimental Materials

2.3. Selective Responses of T. Brevipilosus to Plant Volatiles

2.3.1. Preparation of Monomer Compound Volatile Solution

2.3.2. Preparation of Mixed Plant Compound Solution

2.3.3. Electroantennogram (EAG)

2.3.4. Behavioral Experiment

2.4. Selection of Slow-Release Carriers for Attractant Application in Forest

2.4.1. Preparation of Sustained-Release Materials

2.4.2. Preparation of the Rubber Septum Sustained-Release Dispenser

2.4.3. Preparation and Field Deployment of Sustained-Release Dispensers

2.4.4. Determination of Release Rates

2.5. Simulated Field Experiment for Trap Placement Selection

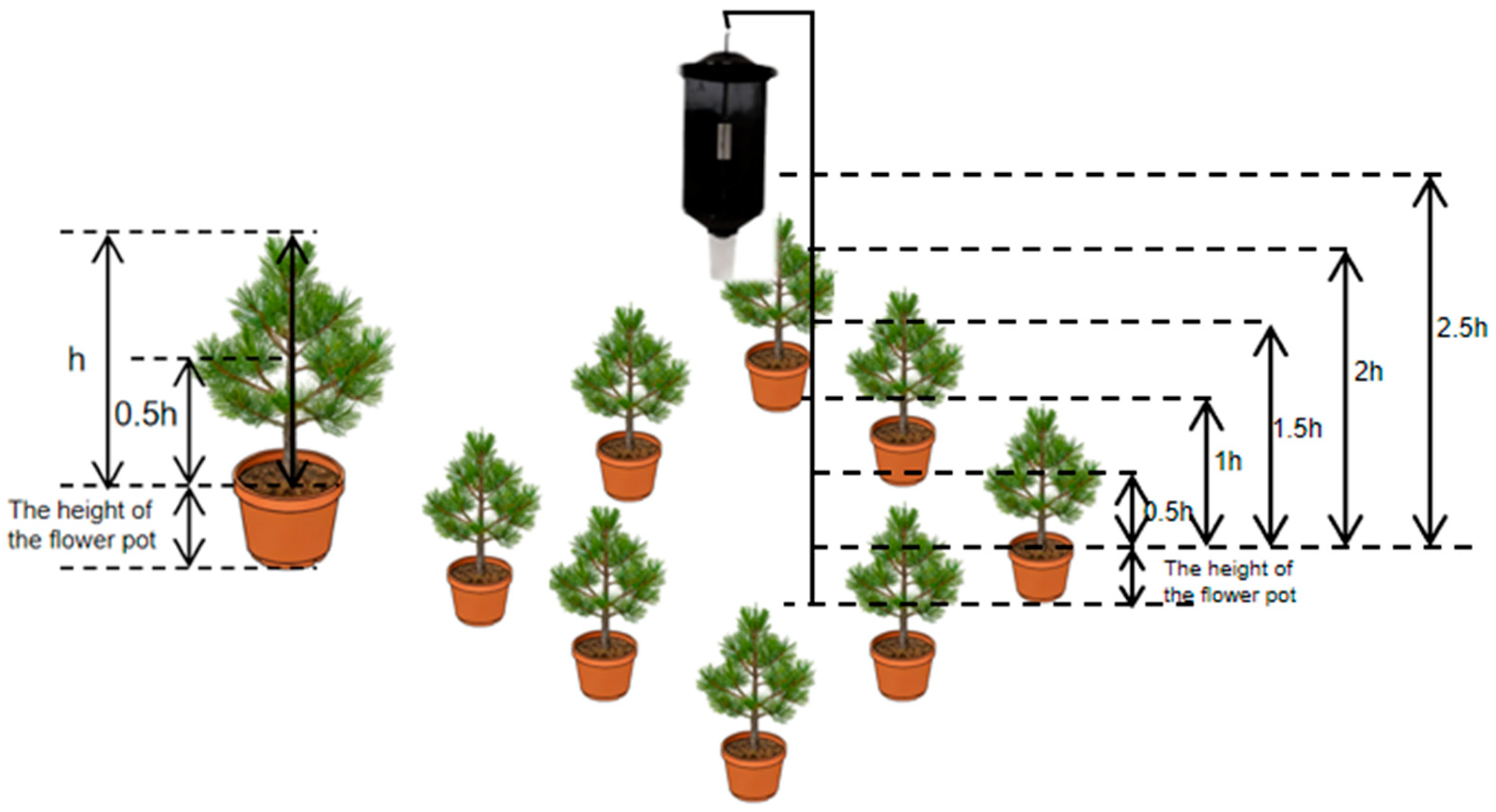

2.5.1. Experiment on Trap Height

2.5.2. Experiment on Trap Placement Within the Forest

2.5.3. Experiment on Canopy Density Selection

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Electrophysiological and Behavioral Responses of T. Brevipilosus to Plant Volatiles

3.1.1. EAG Responses of T. Brevipilosus Adults to 22 Plant Volatiles

3.1.2. EAG Responses of Female Adults to Different Concentrations of Six Plant Volatiles

3.1.3. EAG Responses of Male Adults to Different Concentrations of Six Plant Volatiles

3.1.4. Behavioral Responses of T. Brevipilosus Adults to Four Mixed Plant Volatiles

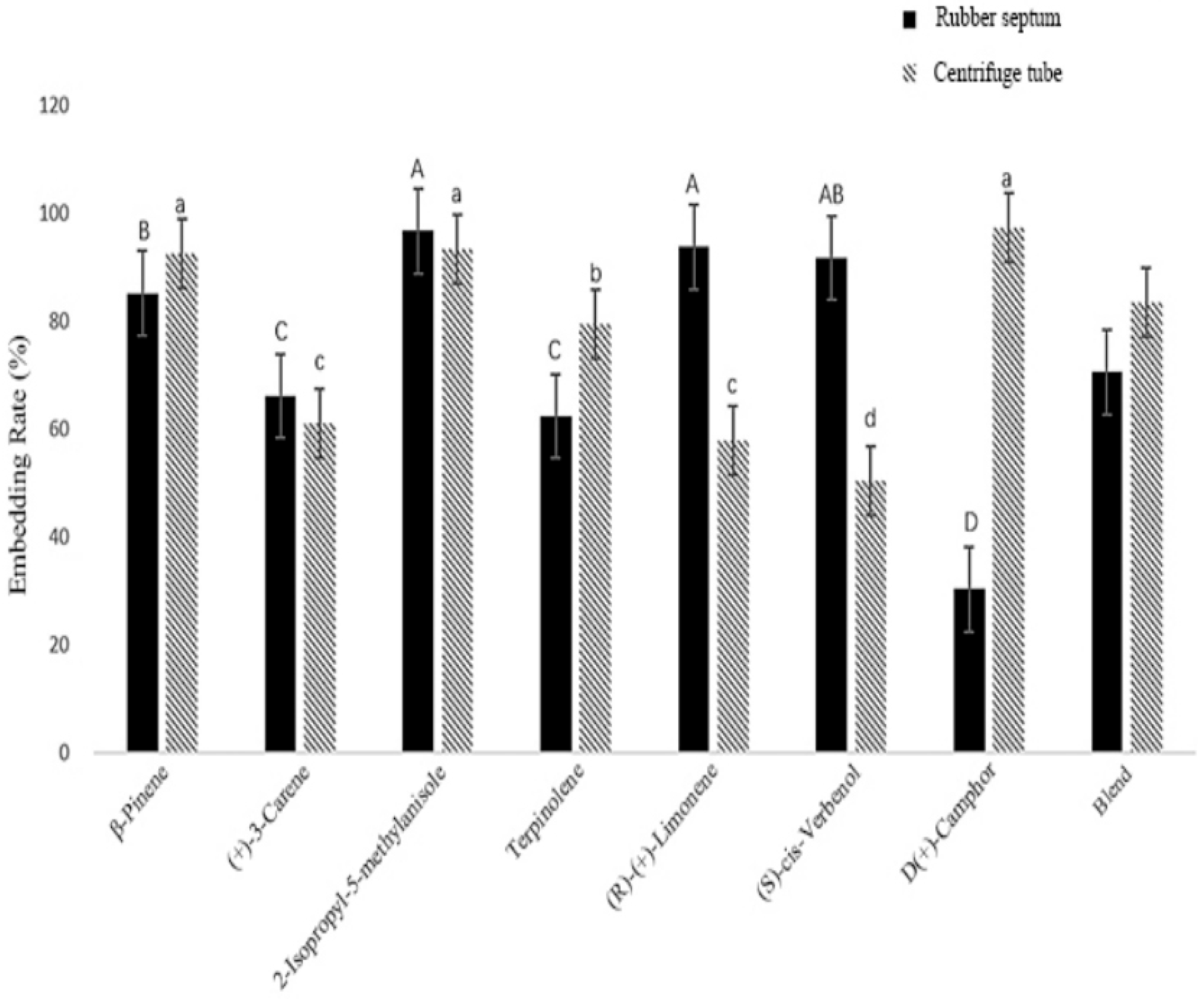

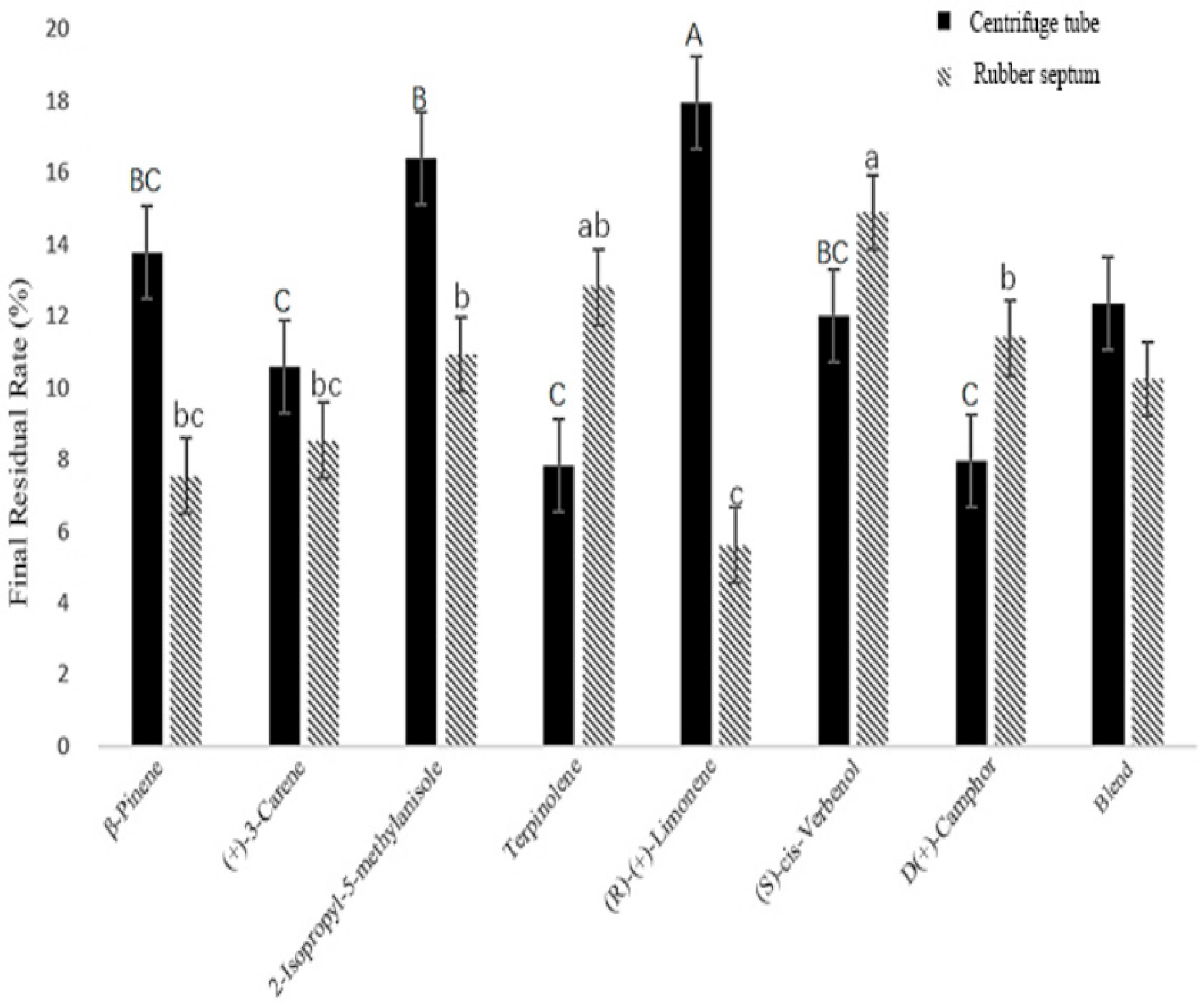

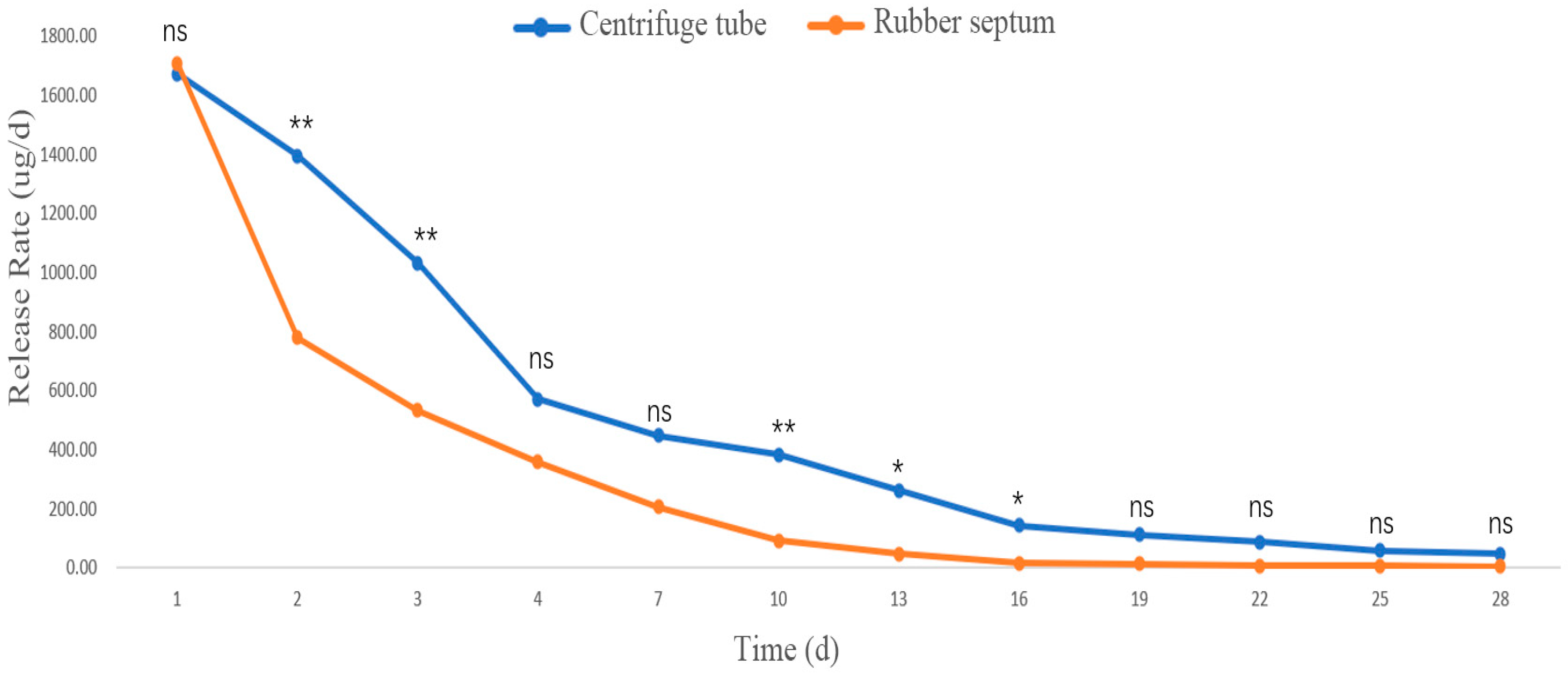

3.2. Selection of a Sustained-Release Carrier for Field Application of the Attractant

3.2.1. Embedding Rate in Different Sustained-Release Materials

3.2.2. Final Residual Rate of Compounds in Different Sustained-Release Materials

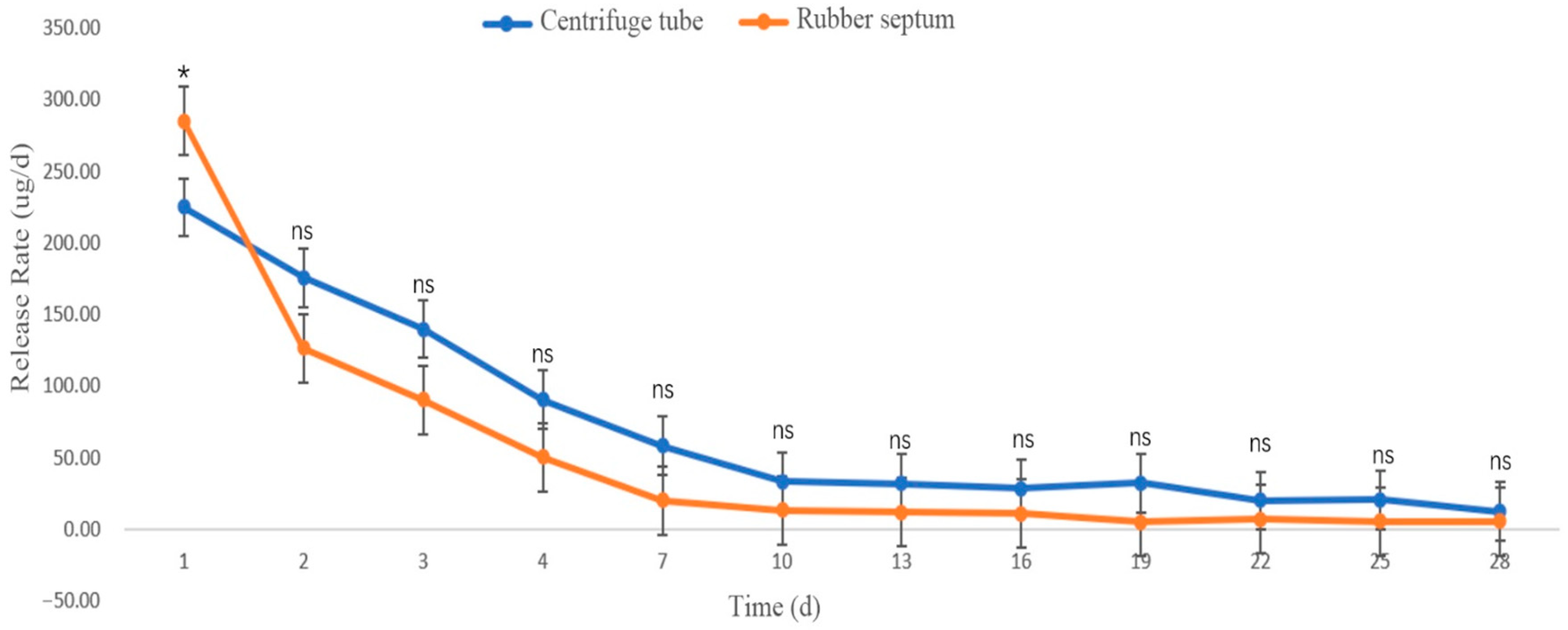

3.2.3. Release Rates in Different Sustained-Release Materials

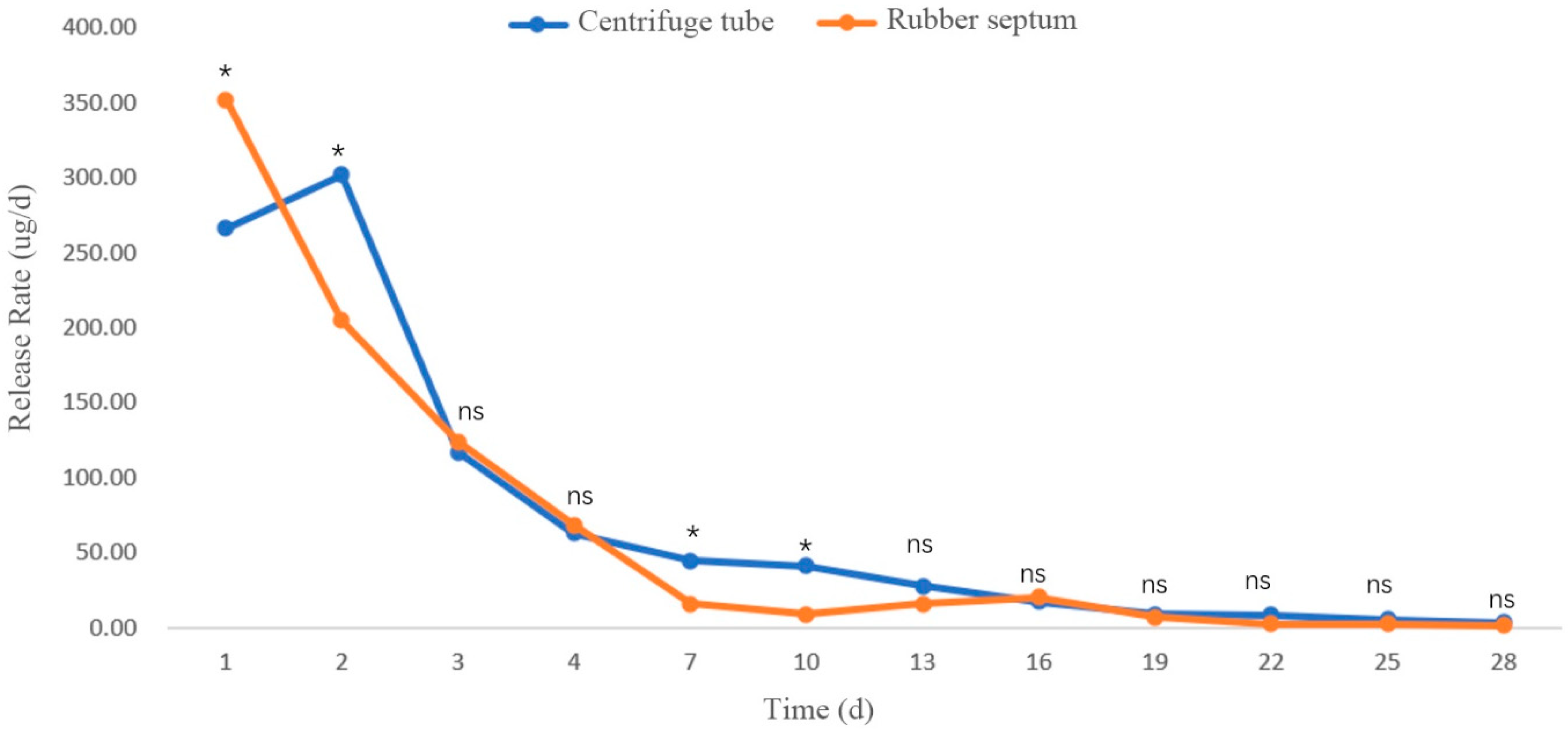

Release Rate of β-Pinene

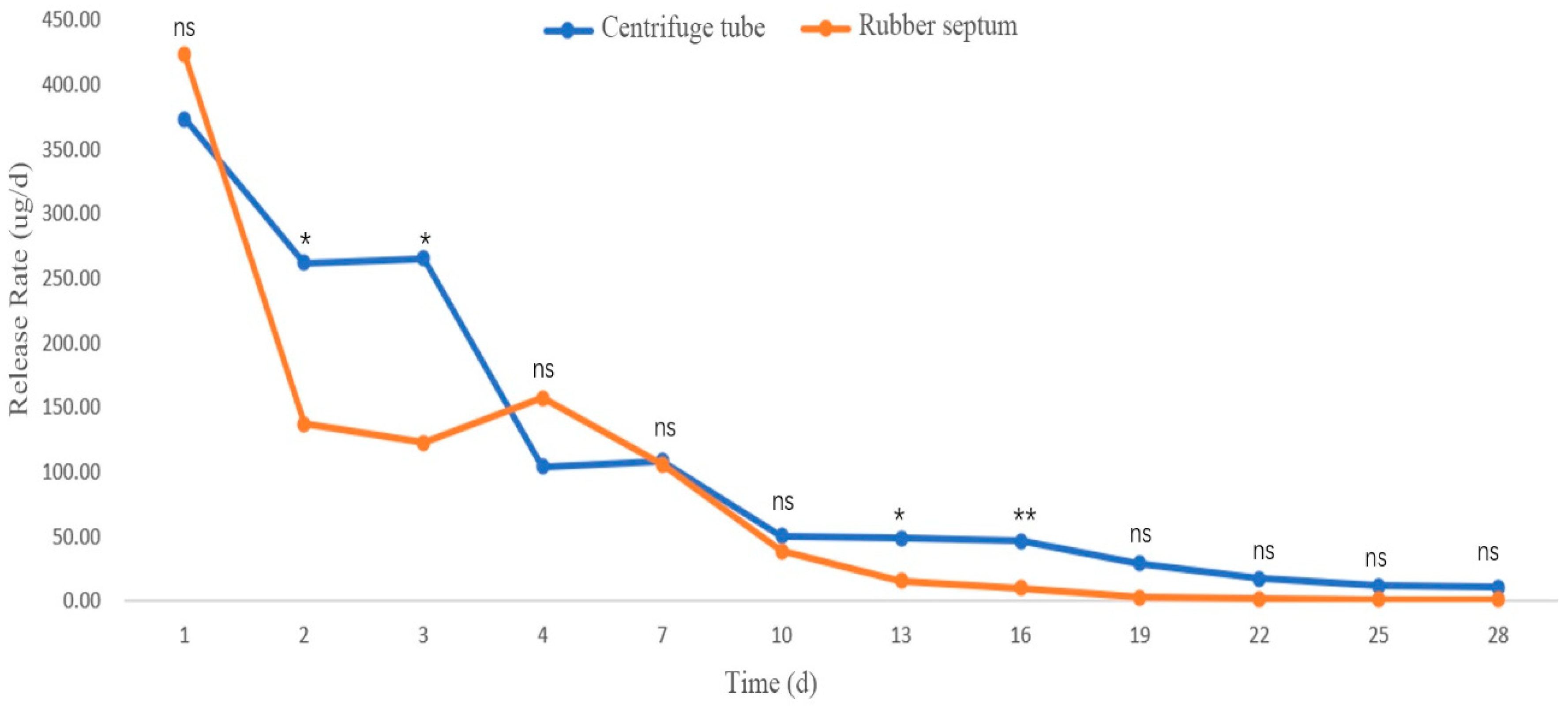

Release Rate of (+)-3-Carene

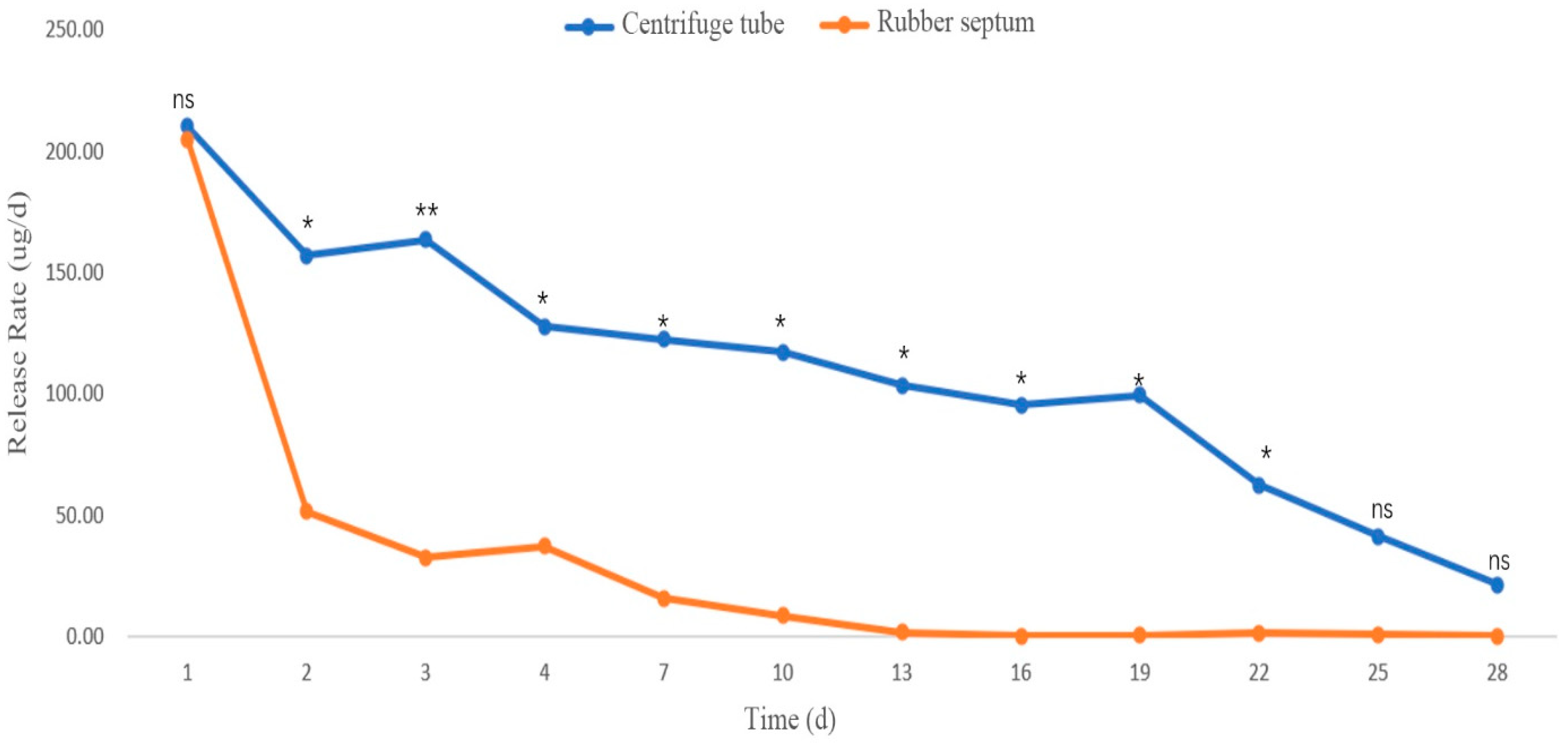

Release Rate of 2-Isopropyl-5-Methylanisole

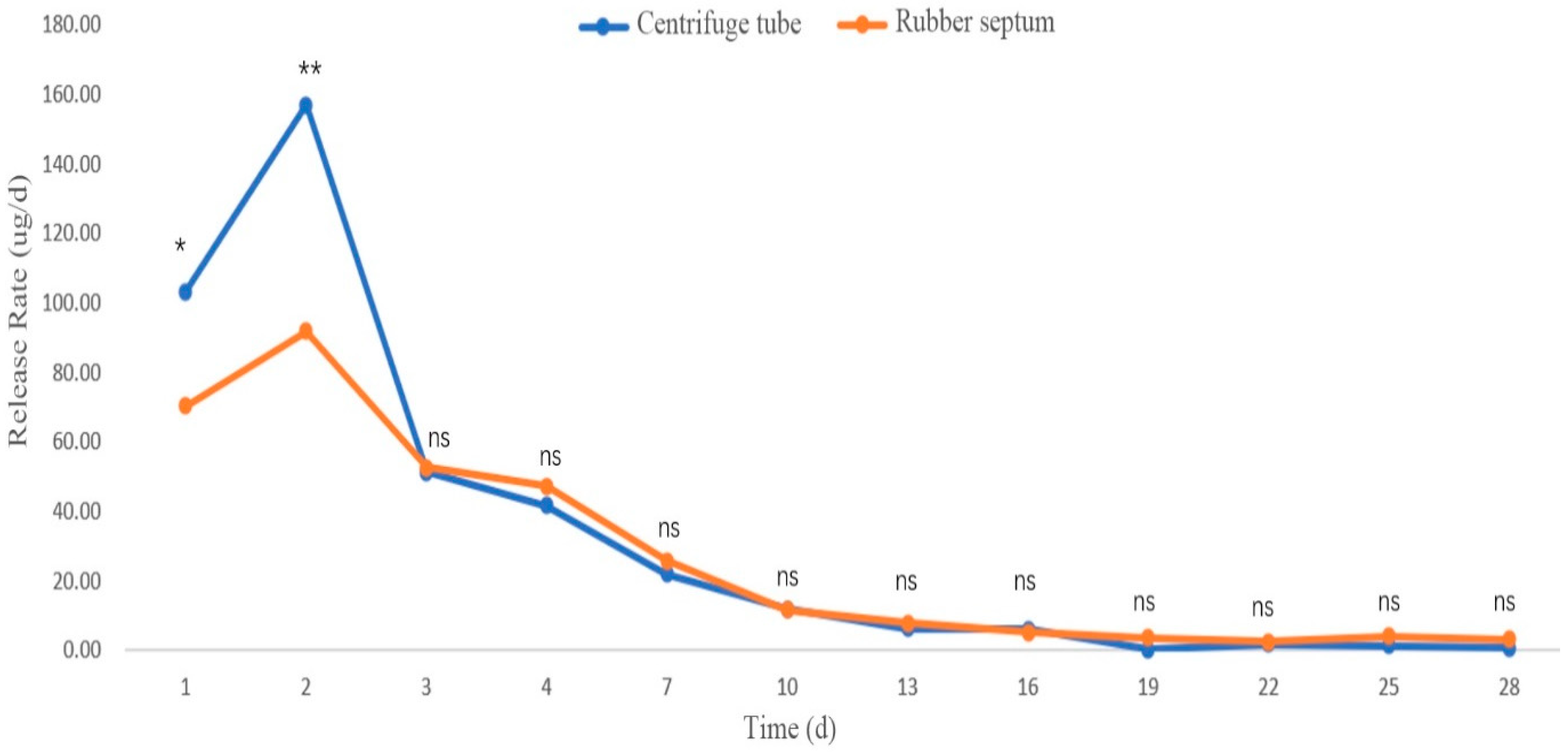

Release Rate of Terpinolene

Release Rate of (R)-(+)-Limonene

Release Rate of (S)-Cis-Verbenol

Release Rate of D(+)-Camphor

Release Rate of the Mixed Compound

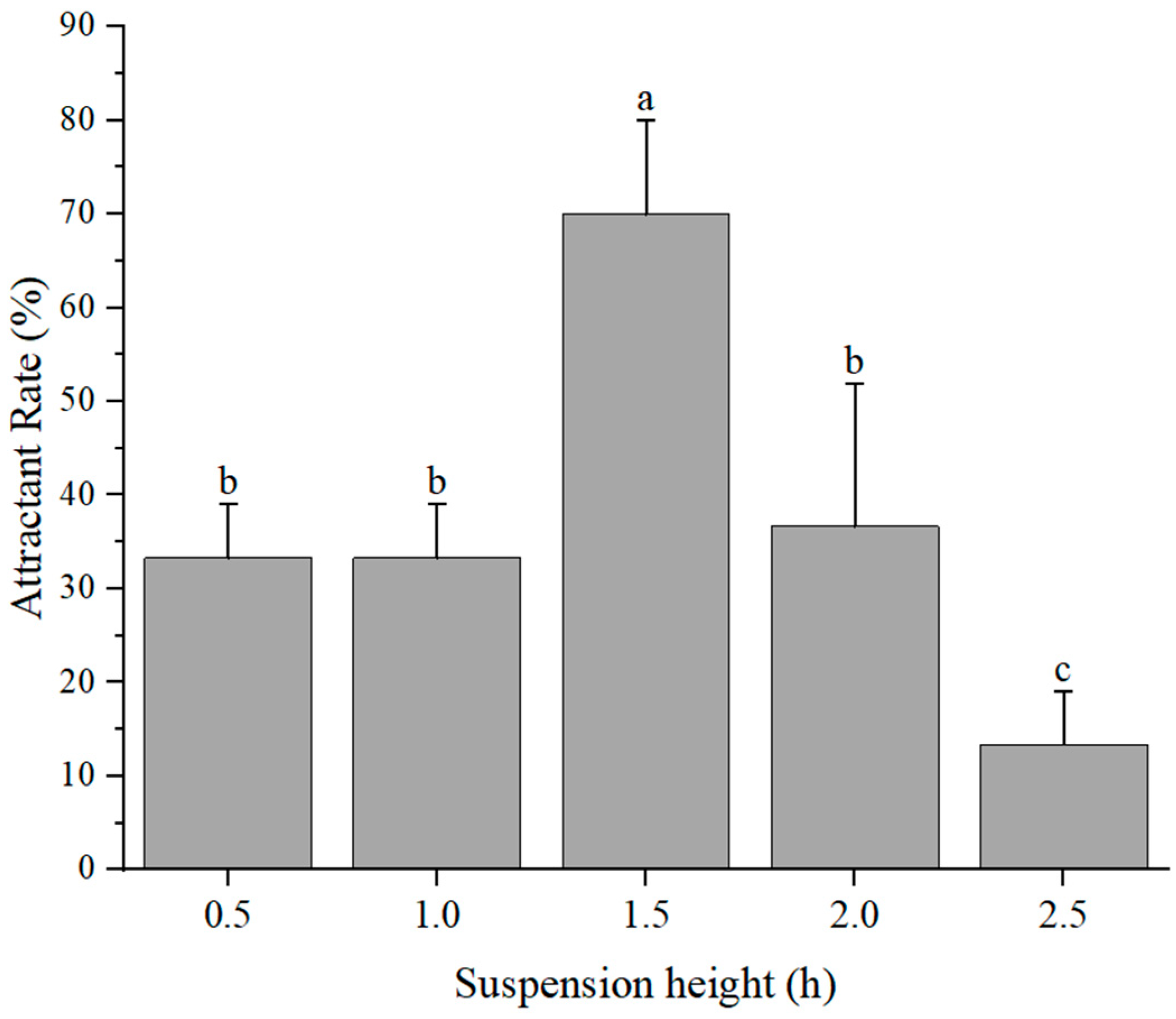

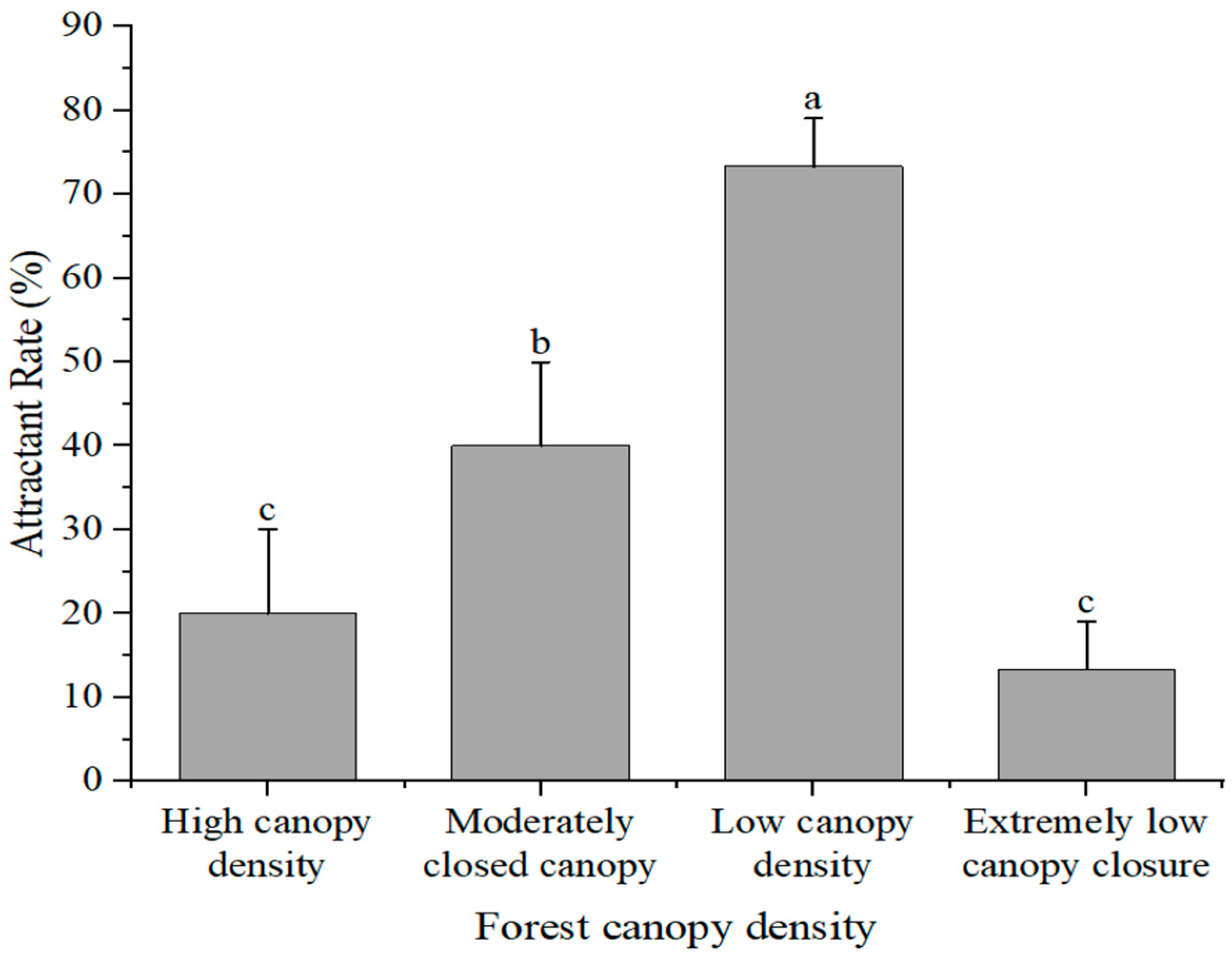

3.3. Simulated Field Deployment: Trap Placement Selection

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Y.L.; Lu, G.Y.; Xiang, Y.T.; Yang, B.; Li, Z. Types, distribution, and quantitative characteristics of sensilla on the head of Tomicus brevipilosus larvae. J. Beijing For. Univ. 2024, 46, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieutier, F.; Långström, B.; Faccoli, M. Chapter 10—The genus Tomicus. In Bark Beetles: Biology and Ecology of Native and Invasive Species; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 371–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.W.; Chen, P.; Wang, Y.X.; Yuan, R.L.; Feng, D.; Li, L.S.; Ye, H.; Pan, Y.; Lv, J.; Zhou, Y.F.; et al. Population structure and succession of Tomicus species in Yunnan Province. For. Res. 2018, 31, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.J.; Zhao, N.; Li, Z.B.; Yang, B. Gut bacterial community structure and diversity of Tomicus brevipilosus. For. Pest. Dis. 2023, 42, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, J.H.; Chong, L.J.; Earle, T.J.; Huber, D.P. Protection of lodgepole pine from attack by the mountain pine beetle, Dendroctonus ponderosae (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) using high doses of verbenone in combination with nonhost bark volatiles. For. Chron. 2003, 79, 685–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Qian, L.B. Reproductive Acoustic Signals and Functional Differentiation of Three Tomicus Species Infesting Yunnan Pine; Southwest Forestry University: Kunming, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H. Tomicus yunnanensis in Yunnan; Yunnan Science and Technology Press: Kunming, China, 2011; pp. 15–67. [Google Scholar]

- Keeling, C.I. Bark beetle research in the postgenomic era. Adv. Insect Physiol. 2016, 50, 137–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.Q.; Han, S.C.; Du, J.W. Roles of plant volatile infochemicals in insect host-selection behavior. J. Environ. Entomol. 2010, 32, 407–414. [Google Scholar]

- Dudareva, N.; Klempien, A.; Muhlemann, J.K.; Kaplan, I. Biosynthesis, function and metabolic engineering of plant volatile organic compounds. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Wu, C.; Zhang, S.; Kong, X.B.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, P. Initial location preference together with aggregation pheromones regulate the attack pattern of Tomicus brevipilosus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) on Pinus kesiya. Forests 2019, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Hu, L.; Yang, B.; Ji, M.; Zhao, N.; Yang, S. Influence analysis of Alnus nepalensis leaves extracts on behavior of pine shoot beetle Tomicus yunnanesis. J. Green. Sci. Technol. 2016, 14, 42–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.L.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Z.M. Behavioral regulation of phytophagous insects by herbivore-induced plant volatiles (HIPVs). Chin. J. Appl. Entomol. 2012, 49, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Zhang, M.D.; Qian, L.B.; Ze, S.Z.; Yang, B.; Li, Z.B. Electrophysiological and behavioral responses of Tomicus yunnanensis to plant volatiles from primarily infected Pinus yunnanensis in Yunnan, Southwest China. J. Environ. Entomol. 2021, 43, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Zhu, J.; Qin, Y. Enhanced attraction of Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) to pheromone-baited traps with the addition of green leaf volatiles. J. Econ. Entomol. 2012, 105, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Lu, J.; Haack, R.A.; Ye, H. Attack pattern and reproductive ecology of Tomicus brevipilosus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) on Pinus yunnanensis in Southwestern China. J. Insect Sci. 2015, 15, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.H.; Gao, W.; Cai, H.; Teng, J. Research Progress on Chemical Ecological Management of Three Tomicus Species (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) in Yunnan Province of China. J. Entomol. Sci. 2025, 60, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, I.; Gershenzon, J.; Köllner, T.G. Differential perception of plant volatile blends by herbivore species sharing a food plant. J. Chem. Ecol. 2020, 46, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, M.; Qian, L.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z. Electrophysiology and behavior of Tomicus yunnanensis to Pinus yunnanensis volatile organic compounds across infestation stages in southwest China. Forests 2025, 16, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Yang, X.X.; Leng, P.S.; Hu, Z.H. Analysis of volatile components in six Syringa species by dynamic headspace adsorption coupled with ATD-GC/MS. Acta Bot. Boreali-Occident. Sin. 2015, 35, 2078–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.J.; Hao, D.J.; Pan, Y.W.; Qu, H.Y.; Fan, B.Q.; Ye, J.R. Behavioral responses of pinewood nematode (Bursaphelenchus xylophilus) to volatiles from several pine species. J. Northeast. For. Univ. 2009, 37, 58–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.L.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, R.G.; Yu, L.S. Comparison of volatile component contents between Pinus yunnanensis and P. kesiya var. langbianensis in Jingdong region. J. Fujian Agric. For. Univ. 2010, 39, 366–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.R.; Zhou, P.Y.; Li, Z.Y.; Fu, R.J.; Yuan, S.Y.; Xiao, C. Comparison of chemical constituents of volatile compounds in needles between healthy and weakened Pinus yunnanensis. Nat. Prod. Res. Dev. 2010, 22, 1048–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.S.; Jia, J.; Chen, H.; Yan, P.D.; Xu, R.X.; Yang, L.Q.; Yang, Z.Q. Analysis of induced resistance volatiles from Pinus yunnanensis var. tenuifolia infested by Tomicus minor using HS-SPME-GC/MS. Sci. Silvae Sin. 2021, 57, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.Y. Studies on Semiochemicals of Three Tomicus species Infesting Pinus yunnanensis. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.H. Studies on Chemical Ecology Relationships Among Three Tomicus Species. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, G.P. Chemical Ecology Mechanisms of Host Selection by Three Tomicus Species During Shoot-Feeding Period in Pinus yunnanensis. Ph.D. Thesis, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.W.; Yang, W.; Yang, H.; Yang, C.P.; Zhu, X.Q.; Liu, F.J.; Jiang, L.H.; Shan, C.Y. Electrophysiological and behavioral responses of Tomicus minor to plant volatiles. Chin. J. Ecol. 2014, 33, 1260–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.X.; Huang, G.Y. Analysis on trapping control effect of Tomicus yunnanensis using semio-chemicals. For. Invent. Plan. 2018, 43, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.Y.; Wang, H.X.; Jia, L.P.; Yang, Y.B. Investigation on population quantity and damage of Tomicus spp. in Hongtashan Nature Reserve. For. Invent. Plan. 2019, 44, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.W.; Li, X.P.; Sun, W.; Zuo, T.T.; Chen, Y.Q. Control efficacy of mass trapping using aggregation pheromone against Ips typographus. For. Pest Dis. 2016, 35, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.L. Preliminary Field Trapping Experiments Using Aggregation Pheromone for the Rubber Wood Borer, Xyleborus affinis; Hainan University: Danzhou, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, M.N.; Schlyter, F.; Hill, S.R.; Dekker, T. What reaches the antenna? How to calibrate odor flux and ligand–receptor affinities. Chem. Senses 2012, 37, 403–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| No. | Compound | CAS | Purity | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | β-Caryophyllene | 87-44-5 | >80% (GC) | Macklin |

| 2 | Camphene | 79-92-5 | 96% (GC) | Macklin |

| 3 | (+)-3-Carene | 498-15-7 | ≥90% (GC) | Macklin |

| 4 | γ-Terpinene | 99-85-4 | 95%(GC) | Macklin |

| 5 | β-Pinene | 18172-67-3 | ≥95% (GC) | Macklin |

| 6 | Myrcene | 123-35-3 | ≥90.0% (GC) | Macklin |

| 7 | α-Pinene | 80-56-8 | 98% (GC) | Macklin |

| 8 | (+)-α-Pinene | 7785-70-8 | 98% (GC) | Macklin |

| 9 | Sabinene | 3387-41-5 | 98% (GC) | Macklin |

| 10 | β-Phellandrene | 555-10-2 | 85% (GC) | Macklin |

| 11 | Terpinolene | 586-62-9 | 85% (GC) | Macklin |

| 12 | D(+)-Camphor | 464-49-3 | ≥96% (GC) | Macklin |

| 13 | (—)-Myrtenol | 515-00-4 | 95% (GC) | Macklin |

| 14 | α-Caryophyllene | 6753-98-6 | 93% (GC) | Macklin |

| 15 | 2-Isopropyl-5-methylanisole | 1076-56-8 | ≥96% (GC) | Macklin |

| 16 | (R)-(+)-Limonene | 5989-27-5 | ≥99% (GC) | Macklin |

| 17 | α-Terpineol | 10482-56-1 | 98% (GC) | Macklin |

| 18 | Bornyl acetate | 76-49-3 | ≥97% (GC) | Macklin |

| 19 | (+)-Longifolene | 475-20-7 | 90% (GC) | Macklin |

| 20 | trans-β-Farnesene | 18794-84-8 | 95% (GC) | Macklin |

| 21 | 2,6-Di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol | 128-37-0 | >99.0% (GC) | Macklin |

| 22 | (S)-cis-Verbenol | 18881-04-4 | ≥95% (GC) | Macklin |

| Compound | Standard Concentration Determination of Concentration (μg/mL) | Calibration Equation | Correlation Coefficient (R2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Pinene | 1, 10, 50, 100, 200 | y = 227.11x − 1259.9 | 0.993 |

| (+)-3-Carene | 1, 10, 50, 100, 200 | y = 812.15x − 3178.2 | 0.9908 |

| 2-Isopropyl-5-methylanisole | 1, 10, 50, 100, 200 | y = 727.26x − 2083 | 0.9904 |

| Terpinolene | 1, 10, 50, 100, 200 | y = 1135.8x − 6476.7 | 0.9921 |

| (R)-(+)-Limonene | 1, 10, 50, 100, 200 | y = 1174.2x − 1317.3 | 0.9904 |

| (S)-cis-Verbenol | 1, 10, 50, 100, 200 | y = 1643x − 1488.6 | 0.9939 |

| D(+)-Camphor | 1, 10, 50, 100, 200 | y = 1490.4x − 1981.1 | 0.9916 |

| Volatile Number | Plant Volatiles | Relative Value of Female Adults (%) | Relative Value of Male Adults (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | β-Pinene | 65 ± 22 a | 11 ± 5 cd |

| 2 | β-Phellandrene | 37 ± 12 bcde | 16 ± 2 cd |

| 3 | Sabinene | 29 ± 5 cdefg | 17 ± 5 bc |

| 4 | Bornyl acetate | 15 ± 1 efg | 18 ± 11 bc |

| 5 | 2-Isopropyl-5-methylanisole | 33 ± 6 bcdef | 42 ± 8 a |

| 6 | Terpinolene | 48 ± 5 abcd | 20 ± 2 bc |

| 7 | (+)-3-Carene | 57 ± 4 ab | 47 ± 8 a |

| 8 | Myrcene | 14 ± 4 efg | 18 ± 1 bc |

| 9 | (−)-Myrtenol | 25 ± 4 defg | 18 ± 6.76 bc |

| 10 | D(+)-Camphor | 13 ± 4 efg | 44 ± 9 a |

| 11 | (+)-α-Pinene | 12 ± 0 efg | 15 ± 0 cd |

| 12 | γ-Terpinene | 12 ± 2 efg | 12 ± 5 cd |

| 13 | β-Caryophyllene | 10 ± 3 fg | 16 ± 5 cd |

| 14 | α-Pinene | 12 ± 4 efg | 11 ± 1 cd |

| 15 | (S)-cis-Verbenol | 15 ± 9 efg | 27 ± 9 b |

| 16 | (+)-Longifolene | 9 ± 4 fg | 6 ± 2 d |

| 17 | trans-β-Farnesene | 12 ± 2 fg | 10 ± 1 cd |

| 18 | (R)-(+)-Limonene | 53 ± 48 abc | 12 ± 4 cd |

| 19 | α-Caryophyllene | 7 ± 2 g | 9 ± 2 cd |

| 20 | α-Terpineol | 8 ± 3 fg | 14 ± 2 cd |

| 21 | Camphene | 16 ± 9 efg | 12 ± 5 cd |

| 22 | 2,6-Di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenol | 13 ± 4 efg | 10 ± 6 cd |

| Compound/Concentration | 1 μg/μL | 10 μg/μL | 100 μg/μL |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Pinene | 16 ± 4 c | 65 ± 16 a | 37 ± 9 b |

| Terpinolene | 30 ± 8 c | 65 ± 8 a | 49 ± 8 b |

| 2-Isopropyl-5-methylanisole | 11 ± 2 b | 15 ± 3 a | 15 ± 4 a |

| D(+)-Camphor | 13 ± 8 ab | 18 ± 6 a | 9 ± 4 b |

| (R)-(+)-Limonene | 49 ± 12 b | 46 ± 3 b | 73 ± 10 a |

| (+)-3-Carene | 57 ± 10 a | 68 ± 10 a | 24 ± 3 b |

| Compound/Concentration | 1 μg/μL | 10 μg/μL | 100 μg/μL |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Pinene | 7 ± 4 b | 16 ± 4 a | 10 ± 4 b |

| Terpinolene | 17 ± 3 b | 27 ± 7 a | 30 ± 4 a |

| 2-Isopropyl-5-methylanisole | 84 ± 15 a | 62 ± 12 b | 29 ± 6 c |

| D(+)-Camphor | 51 ± 12 a | 54 ± 11 a | 25 ± 8 b |

| (R)-(+)-Limonene | 25 ± 6 b | 20 ± 4 b | 32 ± 6 a |

| (+)-3-Carene | 28 ± 5 b | 74 ± 14 a | 18 ± 4 b |

| Composite Number of Mixed Compounds | Compounds | Selection Rate (%) | Reactivity (%) | Control (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10 μg/μL β-Pinene + 10 μg/μL Terpinolene + 1 μg/μL 2-Isopropyl-5-methylanisole + 1 μg/μL D(+)-Camphor + 100 μg/μL (R)-(+)-Limonene + 1 μg/μL (+)-3-Carene | 40 ± 25 b | 67 ± 33 a | 17 ± 15 a |

| 2 | 10 μg/μL β-Pinene + 10 μg/μL Terpinolene + 1 μg/μL 2-Isopropyl-5-methylanisole + 1 μg/μL D(+)-Camphor + 100 μg/μL (R)-(+)-Limonene + 10 μg/μL (+)-3-Carene | 57 ± 20 a | 67 ± 16 a | 67 ± 10 a |

| 3 | 10 μg/μL β-Pinene + 10 μg/μL Terpinolene + 1 μg/μL 2-Isopropyl-5-methylanisole + 10 μg/μL D(+)-Camphor + 100 μg/μL (R)-(+)-Limonene + 1 μg/μL (+)-3-Carene | 27 ± 16 c | 50 ± 28 a | 17 ± 15 a |

| 4 | 10 μg/μL β-Pinene + 10 μg/μL Terpinolene + 1 μg/μL 2-Isopropyl-5-methylanisole + 10 μg/μL D(+)-Camphor + 100 μg/μL (R)-(+)-Limonene + 10 μg/μL (+)-3-Carene | 30 ± 11 bc | 57 ± 27 a | 27 ± 24 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Feng, D.; Zhao, G.; Li, H.; Chen, P. From Laboratory Screening to Greenhouse Flight Bioassay: Development of a Plant-Based Attractant for Tomicus brevipilosus. Forests 2025, 16, 1797. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121797

Wang Y, Feng D, Zhao G, Li H, Chen P. From Laboratory Screening to Greenhouse Flight Bioassay: Development of a Plant-Based Attractant for Tomicus brevipilosus. Forests. 2025; 16(12):1797. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121797

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Ying, Dan Feng, Genying Zhao, Haoran Li, and Peng Chen. 2025. "From Laboratory Screening to Greenhouse Flight Bioassay: Development of a Plant-Based Attractant for Tomicus brevipilosus" Forests 16, no. 12: 1797. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121797

APA StyleWang, Y., Feng, D., Zhao, G., Li, H., & Chen, P. (2025). From Laboratory Screening to Greenhouse Flight Bioassay: Development of a Plant-Based Attractant for Tomicus brevipilosus. Forests, 16(12), 1797. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16121797