Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Forest Carbon Sequestration and Spatial Heterogeneity of Influencing Factors: Evidence from the Beiluo River Basin in the Loess Plateau, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

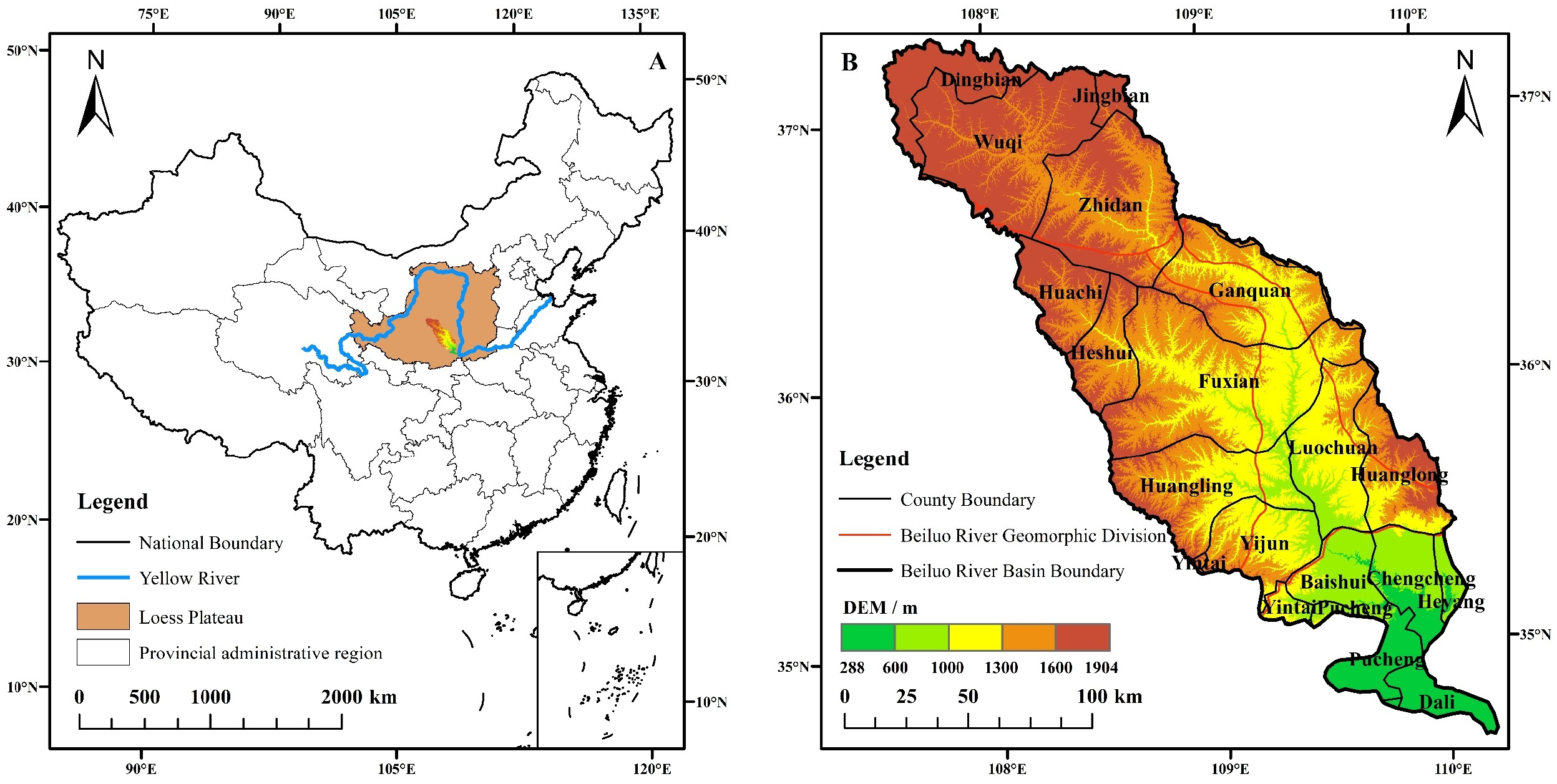

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources and Processing

2.2.1. Land Use Data

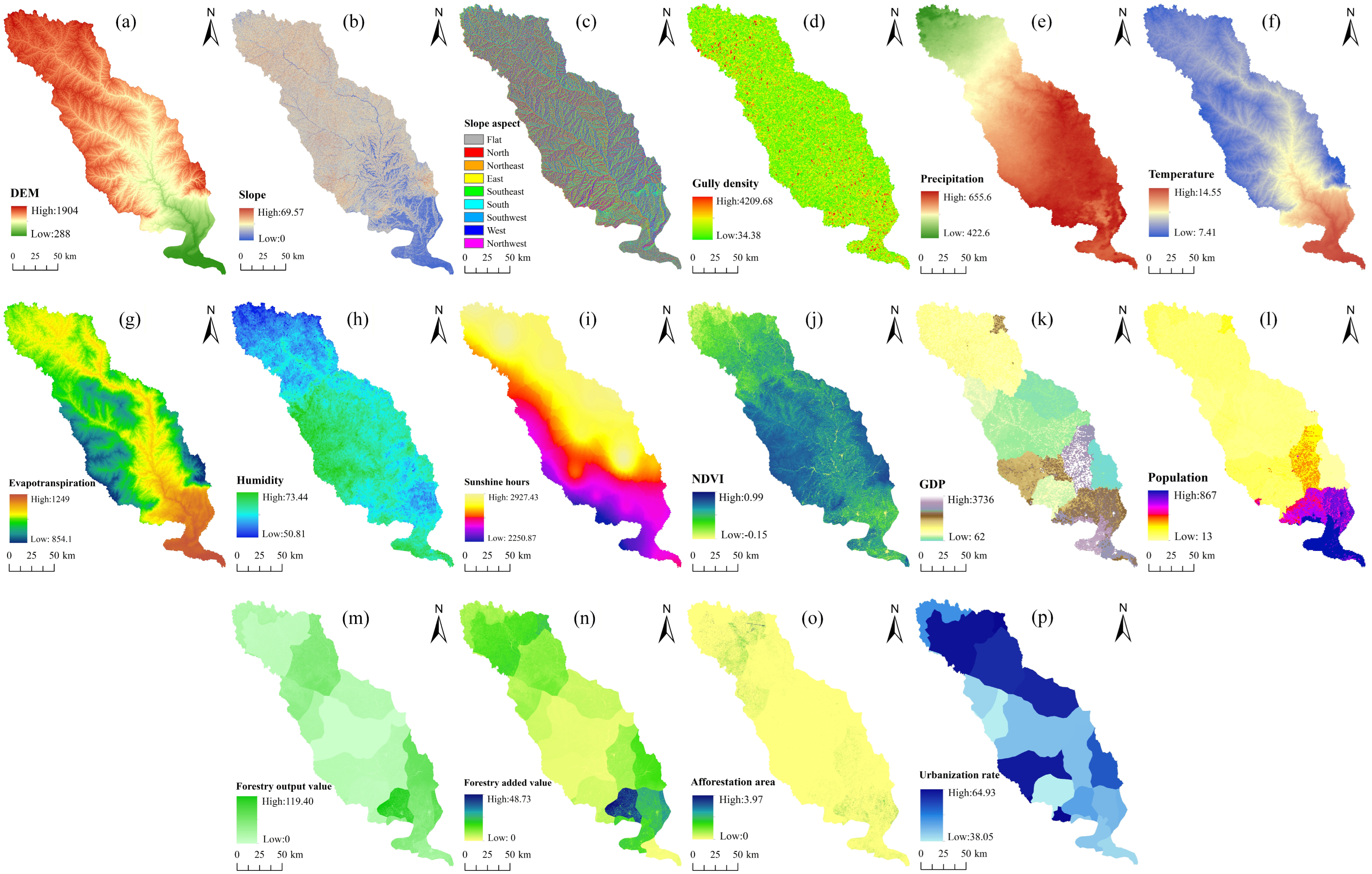

2.2.2. Driving Force Data

2.3. Research Methods

2.3.1. InVEST Model

2.3.2. Spatial Autocorrelation Model

- (1)

- Global spatial autocorrelation. This describes the spatial characteristics of a certain attribute across the entire study area. The calculation formula is as follows:In the formula: n is the number of grids; m is the number of neighboring grids of grid i; is an element in the spatial weight matrix W. When grid i is adjacent to grid j, = 1; otherwise, = 0; and are the values of the carbon sequestration service function of the forest ecosystem in grid cells i and j, respectively; x is the mean value of the carbon sequestration service function of the forest ecosystem; the standardized Z-value is used to test the significance level of the global Moran’s I; and represent the expected value and variance of Moran’s I, respectively.

- (2)

- Local spatial autocorrelation. The degree of correlation between each grid of measurement attributes and adjacent grids is calculated using the following formula:In the formula: , , , , , and have the same meanings as above; denotes variance.

2.3.3. Center of Gravity Model

2.3.4. Geographic Detector Model

2.3.5. Spatio-Temporal Geographic Weighted Regression Model

3. Results

3.1. Multidimensional Evolutionary Characteristics of the Spatio-Temporal Pattern of Forest Carbon Sequestration in the Beiluo River Basin

3.1.1. Temporal Characteristics of Forest Carbon Sequestration from 2000 to 2023

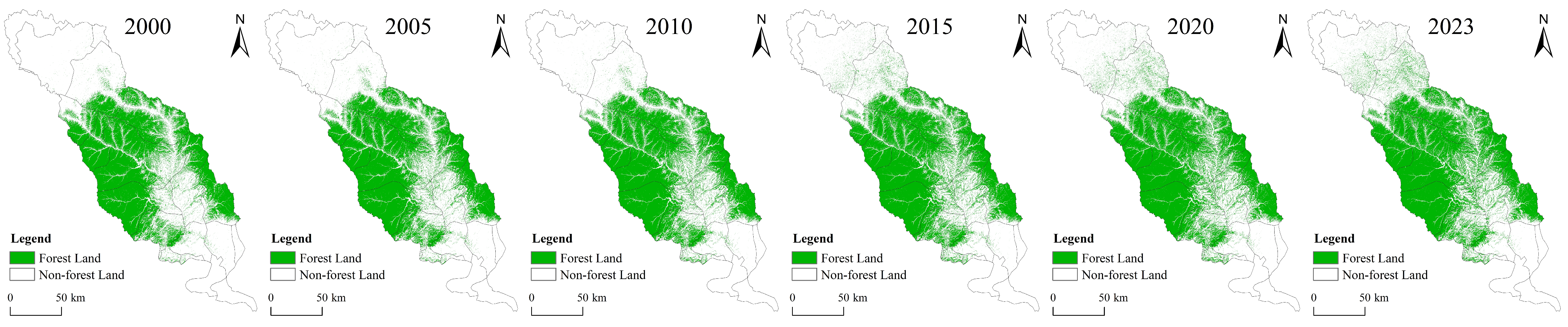

3.1.2. Spatial Pattern Evolution Characteristics of Forest Ecosystem Carbon Sequestration Services from 2000 to 2023

3.1.3. Spatial Correlation of Forest Carbon Sequestration from 2000 to 2023

3.2. Spatial Heterogeneity of Driving Factors for the Spatiotemporal Evolution of Forest Carbon Sequestration in the Beiluo River Basin

3.2.1. Identification of Dominant Factors

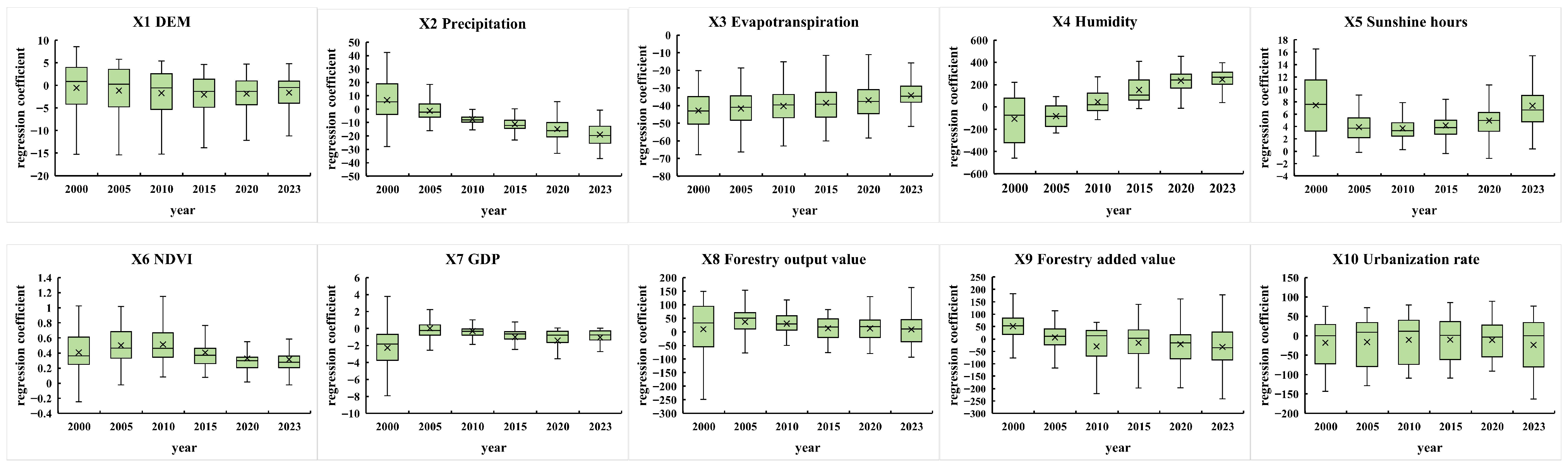

3.2.2. Spatio-Temporal Heterogeneity of Influencing Factors

- (a)

- Time-series evolution analysis of regression coefficients for influencing factors

- (b)

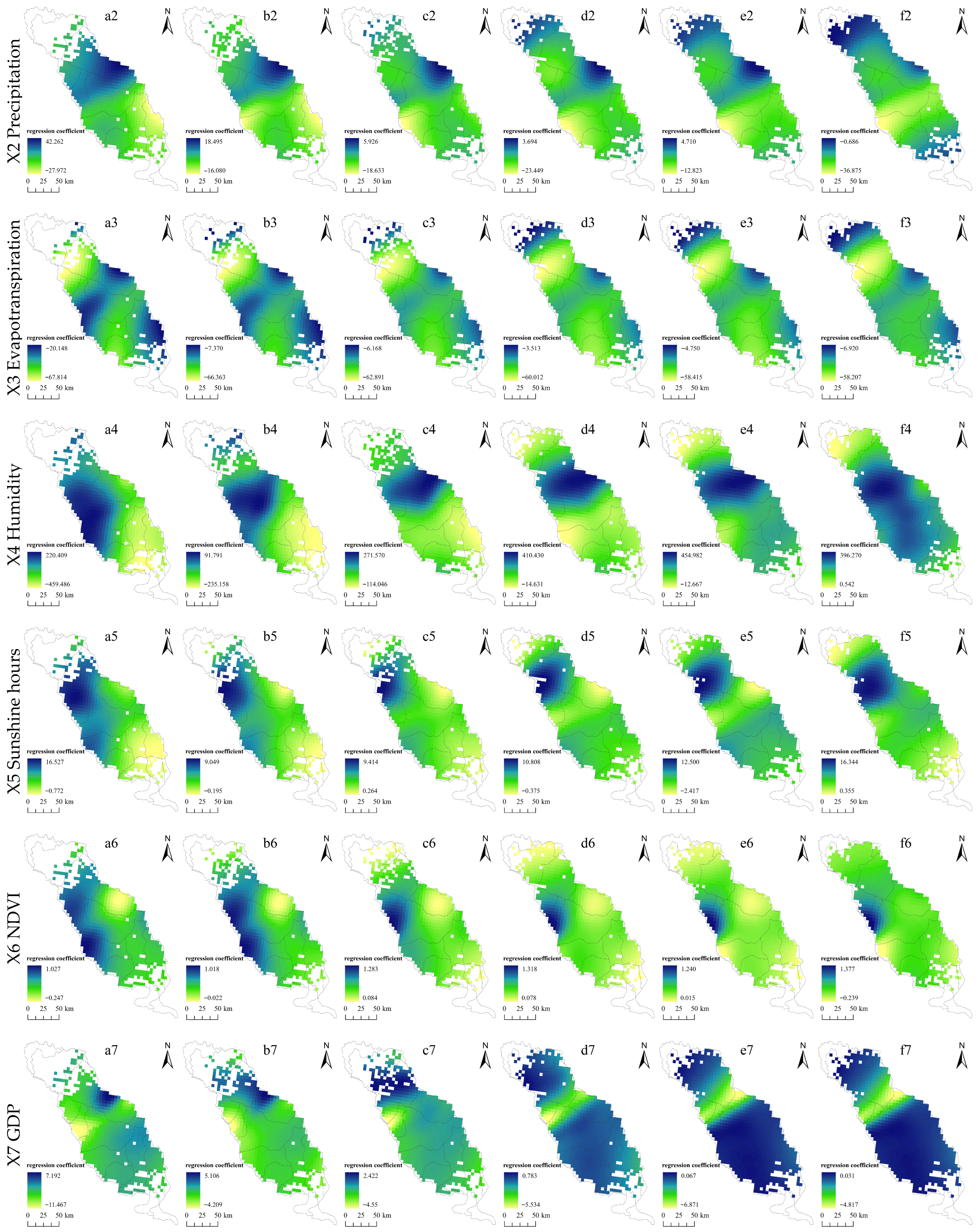

- Spatial differentiation analysis of regression coefficients for influencing factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Temporal Evolution and Spatial Pattern Characteristics of Forest Carbon Sequestration Services

4.2. Spatial Correlation of Forest Carbon Sequestration Services

4.3. Dominance of Driving Factors for Forest Carbon Sequestration Services

4.4. Spatial and Temporal Heterogeneity of Factors Influencing Forest Carbon Sequestration Services

4.5. Research Limitations and Future Prospects

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feng, Q.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xia, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, Y. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Forest Ecosystems and Climate Interplay: A Review. Environ. Rev. 2025, 33, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.; Deng, Q.; Tian, H.; Luo, Y. Climate Change and Carbon Sequestration in Forest Ecosystems. In Handbook of Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–40. ISBN 978-1-4614-6431-0. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.; Li, H. Improving Carbon Sequestration Capacity of Forest Vegetation in China: Afforestation or Forest Management? Forests 2023, 14, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Song, Y. Government Response to Climate Change in China: A Study of Provincial and Municipal Plans. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2016, 59, 1679–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. Response to Climate Change by China’s Forestry and Vision of Forest Carbon Market. In Forest Carbon Practices and Low Carbon Development in China; Lu, Z., Zhang, X., Ma, J., Tang, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 47–69. ISBN 978-981-13-7364-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, C.; Hou, W. Spatiotemporal Carbon Sequestration by Forests among Counties and Grids in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 468, 142971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Pei, H. The Changes of Land Use and Carbon Storage in the Northern Farming-Pastoral Ecotone under the Background of Returning Farmland to Forest (grass). J. Desert Res. 2021, 41, 174–182. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Cao, J.; Adamowski, J.F.; Biswas, A.; Zhou, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C.; Dong, X.; Qin, Y. Assessing the Effects of Ecological Engineering on Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Carbon Storage from 2000 to 2016 in the Loess Plateau Area Using the InVEST Model: A Case Study in Huining County, China. Environ. Dev. 2021, 39, 100641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. Linking Forest Ecosystem Processes, Functions and Services under Integrative Social–Ecological Research Agenda: Current Knowledge and Perspectives. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Birdsey, R.A.; Phillips, O.L.; Houghton, R.A.; Fang, J.; Kauppi, P.E.; Keith, H.; Kurz, W.A.; Ito, A.; Lewis, S.L.; et al. The Enduring World Forest Carbon Sink. Nature 2024, 631, 563–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, M.; Jin, Y.; Song, Q. Effects of Climate Change on the Carbon Sequestration Potential of Forest Vegetation in Yunnan Province, Southwest China. Forests 2022, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Wei, X.; Meng, J.; Chen, W. How to Improve Forest Carbon Sequestration Output Performance: An Evidence from State-Owned Forest Farms in China. Forests 2022, 13, 778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, D.; Yuan, W.; Li, H. Regulation and Resilience: Panarchy Analysis in Forest Socio-Ecosystem of Northeast National Forest Region, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 353, 120295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qiao, X.; Hao, M.; Fan, C.; Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, C. Climate Variability Modulates the Temporal Stability of Carbon Sequestration by Changing Multiple Facets of Biodiversity in Temperate Forests Across Scales. Glob. Change Biol. 2025, 31, e70212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, W.; Xu, L.; Li, M.; Li, O.J.; He, N. Imbalance of Inter-Provincial Forest Carbon Sequestration Rate from 2010 to 2060 in China and Its Regulation Strategy. J. Geogr. Sci. 2023, 33, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetnam, T.L.; Brooks, P.D.; Barnard, H.R.; Harpold, A.A.; Gallo, E.L. Topographically Driven Differences in Energy and Water Constrain Climatic Control on Forest Carbon Sequestration. Ecosphere 2017, 8, e01797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, T.J.A.; Li, X.; Yu, Z.; Liu, S.; Sun, O.J. Reconciliation of Research on Forest Carbon Sequestration and Water Conservation. J. For. Res. 2020, 32, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.G.; Cleveland, C.C.; Wieder, W.R.; Sullivan, B.W.; EDoughty, C.; Dobrowski, S.Z.; Townsend, A.R. Temperature and Rainfall Interact to Control Carbon Cycling in Tropical Forests. Ecol. Lett. 2017, 20, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meena, M.; Yadav, G.; Sonigra, P.; Nagda, A.; Mehta, T.; Swapnil, P.; Harish; Marwal, A.; Kumar, S. Multifarious Responses of Forest Soil Microbial Community Toward Climate Change. Microb. Ecol. 2022, 86, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.Y.; Jeong, S.; Shin, J. Assessing the Impact of Urbanization on Forest Carbon Stocks and Social Costs Using a Machine Learning Approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Wang, K.; Yuan, Y. Toward the Carbon Neutrality: Forest Carbon Sinks and Its Spatial Spillover Effect in China. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 209, 107837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, J.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Wei, X.; Li, M. Active Forest Management Accelerates Carbon Storage in Plantation Forests in Lishui, Southern China. For. Ecosyst. 2022, 9, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez Rodríguez, L.; Hogarth, N.J.; Zhou, W.; Xie, C.; Zhang, K.; Putzel, L. China’s Conversion of Cropland to Forest Program: A Systematic Review of the Environmental and Socioeconomic Effects. Environ. Evid. 2016, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ren, C.; Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Xi, Y. Estimation of Forest Above-Ground Biomass by Geographically Weighted Regression and Machine Learning with Sentinel Imagery. Forests 2018, 9, 582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.; Han, X.; Zhou, H. Spatially Varying Patterns of Afforestation/Reforestation and Socio-Economic Factors in China: A Geographically Weighted Regression Approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 153, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, B.; Huang, C.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Q.; Li, M. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Driving Factors of Soil Erosion in the Beiluo River Basin, Loess Plateau, China. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 155, 110976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Nie, S.; Qian, M. Ecological Restoration in the Loess Plateau, China Necessitates Targeted Management Strategy: Evidence from the Beiluo River Basin. Forests 2023, 14, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, Q.; Jiang, J.; Pei, Y. Pixel-Level Land Cover Change Detection in the Loess Plateau Based on Different Data. In Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Geoscience and Remote Sensing Mapping (ICGRSM 2023), Lianyungang, China, 13–15 October 2013; Available online: https://www.spiedigitallibrary.org/conference-proceedings-of-spie/12980/129800Z/Pixel-level-land-cover-change-detection-in-the-Loess-Plateau/10.1117/12.3020898.short (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Zhou, X.; Wen, Z.; Wu, S. How Topographic Factors Regulate Vegetation Vigor in Reservoir Drawdown Zones with Different Levels of Hydrological Disturbances? Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 114006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Wang, X. Inconsistent Influence of Temperature, Precipitation, and CO2 Variations on the Plateau Alpine Vegetation Carbon Flux. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Miao, C.; Li, X.; Kong, D.; Gou, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S. Effects of Vegetation Changes and Multiple Environmental Factors on Evapotranspiration Across China Over the Past 34 Years. Earth’s Future 2022, 10, e2021EF002564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhu, Z. Exploring the Best-Matching Plant Traits and Environmental Factors for Vegetation Indices in Estimates of Global Gross Primary Productivity. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, M.M. Macro-Level Factors Shaping Residential Location Choices: Examining the Impacts of Density and Land-Use Mix. Land 2023, 12, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, K.; Huang, H.; Yang, Y. A Review of Eco-Product Value Realization and Eco-Industry with Enlightenment toward the Forest Ecosystem Services in Karst Ecological Restoration. Forests 2023, 14, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Fu, Q.; Fang, S.; Wu, J.; He, P.; Quan, Z. Effects of Rapid Urbanization on Vegetation Cover in the Metropolises of China over the Last Four Decades. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 107, 105458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Zhang, J.; Meng, X.; Xu, T.; Song, Y. Long-Term Spatio-Temporal Precipitation Variations in China with Precipitation Surface Interpolated by ANUSPLIN. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, T.; Guangchao, C.; Zhen, C.; Fang, L.; Meiliang, Z. A Comparative Study of Two Temperature Interpolation Methods: A Case Study of the Middle East of Qilian Mountain. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 780, 072038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; He, Z.; Du, J.; Chen, L.; Lin, P.; Fang, S. Assessing the Effects of Ecological Engineering on Carbon Storage by Linking the CA-Markov and InVEST Models. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 98, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Li, L.; Zhu, R.; Luo, C.; Lu, X.; Sun, M.; Xu, B. Assessing Land-Use Changes and Carbon Storage: A Case Study of the Jialing River Basin, China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 15984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, Z.; Zubair, M.; Zha, Y.; Mehmood, M.S.; Rehman, A.; Fahd, S.; Nadeem, A.A. Predictive Modeling of Regional Carbon Storage Dynamics in Response to Land Use/Land Cover Changes: An InVEST-Based Analysis. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Fang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, T.; Liu, K. Exploring Future Ecosystem Service Changes and Key Contributing Factors from a “Past-Future-Action” Perspective: A Case Study of the Yellow River Basin. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.A.; Starr, M.; Clark, B.J.F. Tree Biomass and Soil Organic Carbon Densities across the Sudanese Woodland Savannah: A Regional Carbon Sequestration Study. J. Arid. Environ. 2013, 89, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Hu, K.; Liu, W.; Wu, H. Scientometric Analysis for Spatial Autocorrelation-Related Research from 1991 to 2021. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Chen, Y.; Tan, H.; Zhou, A.; Chen, G.; Chen, Y. Estimating Regional PM2.5 Concentrations in China Using a Global-Local Regression Model Considering Global Spatial Autocorrelation and Local Spatial Heterogeneity. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, X.; Xing, W.; Li, X.; Yan, M.; Yuan, Y. Impacts of Changing Climate on the Distribution of Migratory Birds in China: Habitat Change and Population Centroid Shift. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 127, 107729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, W. Spatial Distribution Characteristics of Suitable Planting Areas for Pyrus Species under Climate Change in China. Plants 2023, 12, 1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C. Geodetector: Principle and Prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Fotheringham, A.S.; Crespo, R.; Yao, J. Geographical and Temporal Weighted Regression (GTWR). Geogr. Anal. 2015, 47, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Yang, J. Spatial–Temporal Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Land-Use Carbon Emissions: An Empirical Analysis Based on the GTWR Model. Land 2023, 12, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wu, B.; Barry, M. Geographically and Temporally Weighted Regression for Modeling Spatio-Temporal Variation in House Prices: International. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2010, 24, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X. Quantifying Influences of Natural and Anthropogenic Factors on Vegetation Changes Based on Geodetector: A Case Study in the Poyang Lake Basin, China. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Luo, X.; Qi, L.; Liao, X.; Chen, C. Simulation of the Spatiotemporal Distribution of PM2.5 Concentration Based on GTWR-XGBoost Two-Stage Model: A Case Study of Chengdu Chongqing Economic Circle. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, A.; King, B. Evaluating China’s Slope Land Conversion Program as Sustainable Management in Tianquan and Wuqi Counties. J. Environ. Manag. 2011, 92, 1916–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Shangguan, Z.P.; Sweeney, S. “Grain for Green” Driven Land Use Change and Carbon Sequestration on the Loess Plateau, China. Scientific Reports. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, R.; Fu, B.; Liu, G.; Liu, S. Soil Carbon Sequestration Potential for “Grain for Green” Project in Loess Plateau, China. Environ. Manag. 2011, 48, 1158–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Hashimoto, S.; Liu, L. Integrated Assessment of Land-Use/Land-Cover Dynamics on Carbon Storage Services in the Loess Plateau of China from 1995 to 2050. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 120, 106939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Chen, W.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, X.; Du, P.; Guo, C.; Ju, Y.; Pu, C. Effects of Land-Use Management on Soil Erosion: A Case Study in a Typical Watershed of the Hilly and Gully Region on the Loess Plateau of China. CATENA 2021, 206, 105551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Li, S.; Zhou, Z. Impacts of Ecological Engineering Interventions on Carbon Sequestration: Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms in Karst Rocky Desertification Control. Forests 2025, 16, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, J.; Jiao, F.; Zhang, K.; Ye, X.; Gong, H.; Lin, N.; Zou, C. Ecological Engineering Induced Carbon Sinks Shifting from Decreasing to Increasing during 1981–2019 in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 864, 161037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, L.; Wang, J.; Ye, H.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Z. Research on Zoning and Carbon Sink Enhancement Strategies for Ecological Spaces in Counties with Different Landform Types. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye-Danquah, J.; Antwi, E.K.; Saito, O.; Abekoe, M.K.; Takeuchi, K. Impact of Farm Management Practices and Agricultural Land Use on Soil Organic Carbon Storage Potential in the Savannah Ecological Zone of Northern Ghana. J. Disaster Res. 2014, 9, 484–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, W.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z. Assessing Effects of the Returning Farmland to Forest Program on Vegetation Cover Changes at Multiple Spatial Scales: The Case of Northwest Yunnan, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 304, 114303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doimo, I.; Masiero, M.; Gatto, P. Forest and Wellbeing: Bridging Medical and Forest Research for Effective Forest-Based Initiatives. Forests 2020, 11, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Li, T.; Yang, M.; Zhou, X.; Peng, C. The Effects of Environmental Factors and Plant Diversity on Forest Carbon Sequestration Vary between Eastern and Western Regions of China. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 437, 140371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Yang, R.; Dong, Y.-X.; Liu, Y.-X.; Qiu, L.-R. The Influence of Rapid Urbanization and Land Use Changes on Terrestrial Carbon Sources/Sinks in Guangzhou, China. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 70, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Type | Data Name | Year | Data Accuracy | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topographic factors | X1 DEM | 2020 | 30 m | https://www.gscloud.cn (accessed on 28 June 2025) |

| X2 Slope | 2020 | 30 m | DEM | |

| X3 Slope aspect | 2020 | 30 m | DEM | |

| X4 Gully density | 2020 | 30 m | DEM | |

| Natural ecological factors | X5 Precipitation | 2000–2023 | 1 km | https://data.cma.cn/ (accessed on 25 June 2025) |

| X6 Temperature | 2000–2023 | 1 km | https://data.cma.cn/ (accessed on 25 June 2025) | |

| X7 Evapotranspiration | 2000–2023 | 1 km | https://data.cma.cn/ (accessed on 25 June 2025) | |

| X8 Humidity | 2000–2023 | 1 km | https://data.cma.cn/ (accessed on 25 June 2025) | |

| X9 Sunshine hours | 2000–2023 | 1 km | https://data.cma.cn/ (accessed on 25 June 2025) | |

| X10 NDVI | 2000–2023 | 30 m | https://www.resdc.cn/ (accessed on 27 June 2025) | |

| Socioeconomic factors | X11 GDP | 2000–2020 | 1 km | https://www.resdc.cn/ (accessed on 27 June 2025) |

| X12 POP | 2000–2020 | 1 km | https://www.resdc.cn/ (accessed on 27 June 2025) | |

| X13 Forestry output value | 2000–2023 | 30 m | <Yan’an Statistical Yearbook>, <Weinan City Statistical Yearbook>, <Yulin City Statistical Yearbook>, <Qingyang City Statistical Yearbook> | |

| X14 Forestry added value | 2000–2023 | 30 m | ||

| X15 Afforestation area | 2000–2023 | 30 m | ||

| X16 Urbanization rate | 2000–2023 | 1 km |

| Land Use Type | Aboveground Carbon Density | Underground Carbon Density | Soil Carbon Density | Dead Organic Matter Carbon Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forest Land | 15.77 | 43.37 | 59.50 | 4.00 |

| Area | Area (km2) | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 | Increase | Growth Rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire basin | 25,706.44 | 13,193.18 | 13,557.48 | 13,398.06 | 14,266.75 | 14,540.52 | 14,980.83 | 1787.65 | 13.55 | |

| Upstream area | Jingbian County | 235.21 | 1.08 | 1.35 | 1.6 | 4.35 | 5.31 | 6.86 | 5.78 | 535.19 |

| Dingbian County | 1074.9 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.73 | 0.73 | ||

| Wuqi County | 3199.89 | 6.26 | 12.61 | 16.8 | 100.82 | 137 | 237.34 | 231.08 | 3691.37 | |

| Zhidan County | 2808.98 | 696.3 | 700.98 | 693.13 | 828.67 | 919.18 | 1030.5 | 334.24 | 48.00 | |

| Huachi County | 1070.3 | 645.35 | 646.34 | 632.03 | 648.14 | 665.89 | 696.67 | 51.32 | 7.95 | |

| Heshui County | 969.95 | 1153.1 | 1150.9 | 1139.4 | 1150.8 | 1159.7 | 1173.2 | 20.06 | 1.74 | |

| Total | 9359.23 | 2502.1 | 2512.2 | 2483 | 2733 | 2887.3 | 3145.3 | 643.21 | 25.71 | |

| Midstream area | Ganquan County | 2173.05 | 1732.2 | 1756.2 | 1758 | 1804.8 | 1841.9 | 1894.8 | 162.67 | 9.39 |

| Fu County | 4063.64 | 3897.5 | 3975.2 | 4048.4 | 4124.7 | 4196.2 | 4313.1 | 415.63 | 10.66 | |

| Luochuan County | 1650.34 | 578.85 | 641.01 | 694.89 | 723.7 | 752.26 | 775.22 | 196.37 | 33.92 | |

| Huanglong County | 1329.06 | 1245.7 | 1289 | 1294.4 | 1281.9 | 1264.2 | 1255.9 | 10.12 | 0.81 | |

| Huangling County | 2105.39 | 2147.6 | 2200.2 | 2251.2 | 2290.8 | 2323 | 2350.4 | 202.79 | 9.44 | |

| Yijun County | 1257.9 | 777.81 | 848.22 | 903.35 | 901.44 | 865.73 | 822.07 | 44.26 | 5.69 | |

| Total | 12,579.38 | 10,380 | 10,710 | 10,950 | 11,127 | 11,243 | 11,412 | 1031.8 | 9.94 | |

| Downstream area | Baishui County | 881.39 | 95.45 | 107.55 | 122.23 | 130.91 | 133.61 | 141.81 | 46.36 | 48.57 |

| Chengcheng County | 971.21 | 12.14 | 12.98 | 13.84 | 13.81 | 10.83 | 8.92 | −3.22 | −26.52 | |

| Heyang County | 235.97 | 0.42 | 0.3 | 0.28 | 0.3 | 0.19 | 0.16 | −0.26 | −61.90 | |

| Yintai District, Tongchuan City | 234.24 | 63.47 | 71.69 | 95 | 109.56 | 113 | 119.25 | 55.78 | 87.88 | |

| Pucheng County | 770.12 | 9.6 | 11.5 | 17.71 | 20.17 | 20.25 | 20.12 | 10.52 | 109.58 | |

| Dali County | 536.56 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 3629.49 | 181.08 | 204.03 | 249.07 | 274.75 | 277.89 | 290.26 | 109.18 | 60.29 | |

| Landform type | High plateau gully area | 5110.01 | 2083.8 | 2305.7 | 2492.3 | 2623.5 | 2726 | 2847 | 763.25 | 36.63 |

| Terraced plain area | 3638.52 | 155.58 | 177 | 219.13 | 243.26 | 246.32 | 257.67 | 102.09 | 65.62 | |

| Hilly and gully area | 6775.66 | 279.97 | 290.86 | 299.82 | 521.38 | 645.73 | 852.68 | 572.71 | 204.56 | |

| Rocky mountain forest area | 10,182.25 | 10,674 | 10,784 | 10,802 | 10,879 | 10,922 | 11,023 | 349.61 | 3.28 | |

| Year | Center of Gravity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X Coordinate | Y Coordinate | Moving Distance/m | Moving Direction/° | |

| 2000 | 1,949,552.561 | 4,100,079.171 | 1073.963 | 324.5288 |

| 2005 | 1,950,427.204 | 4,099,455.957 | 1227.114 | 316.8478 |

| 2010 | 1,951,322.432 | 4,098,616.686 | 1590.207 | 124.2673 |

| 2015 | 1,950,427.058 | 4,099,930.865 | 1091.284 | 118.2904 |

| 2020 | 1,949,909.854 | 4,100,891.802 | 1840.905 | 123.3128 |

| 2023 | 1,948,898.811 | 4,102,430.218 | ||

| Year | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moran’s I | 0.764 | 0.788 | 0.791 | 0.802 | 0.747 | 0.783 |

| Z | 648.609 | 509.116 | 518.316 | 879.296 | 1305.120 | 987.472 |

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Independent Variable | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2023 | q-Mean | Explanatory Power Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | 0.2525 | 0.2066 | 0.1723 | 0.1504 | 0.1423 | 0.3463 | 0.2117 | 7 |

| X2 | 0.0101 | 0.0152 | 0.0171 | 0.0263 | 0.0271 | 0.1566 | 0.0421 | 14 |

| X3 | 0.0182 | 0.0155 | 0.0156 | 0.0138 | 0.0122 | 0.0722 | 0.0246 | 15 |

| X4 | 0.011 | 0.011 | 0.0111 | 0.0113 | 0.0109 | 0.0095 | 0.0108 | 16 |

| X5 | 0.0914 | 0.1433 | 0.1894 | 0.258 | 0.399 | 0.4455 | 0.2544 | 4 |

| X6 | 0.3341 | 0.2538 | 0.1968 | 0.1696 | 0.1497 | 0.1855 | 0.2149 | 6 |

| X7 | 0.6622 | 0.6399 | 0.5767 | 0.609 | 0.603 | 0.2544 | 0.5575 | 1 |

| X8 | 0.1145 | 0.1837 | 0.1999 | 0.3232 | 0.4725 | 0.4323 | 0.2877 | 3 |

| X9 | 0.1801 | 0.1616 | 0.3442 | 0.4122 | 0.1208 | 0.2281 | 0.2411 | 5 |

| X10 | 0.5816 | 0.6295 | 0.5876 | 0.5308 | 0.4547 | 0.365 | 0.5249 | 2 |

| X11 | 0.2457 | 0.1806 | 0.0702 | 0.2497 | 0.4064 | 0.0987 | 0.2085 | 8 |

| X12 | 0.1504 | 0.1111 | 0.0986 | 0.0666 | 0.0663 | 0.0263 | 0.0866 | 12 |

| X13 | 0.0892 | 0.049 | 0.1706 | 0.1517 | 0.1371 | 0.2088 | 0.1344 | 10 |

| X14 | 0.1897 | 0.0698 | 0.2043 | 0.2101 | 0.2629 | 0.2062 | 0.1905 | 9 |

| X15 | 0.056 | 0.0779 | 0.0209 | 0.2112 | 0.0431 | 0.0793 | 0.0814 | 13 |

| X16 | 0.1056 | 0.0786 | 0.1341 | 0.2234 | 0.0751 | 0.093 | 0.1183 | 11 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dong, L.; Li, H.; Deng, Y.; Wu, H.; Khan, H.S. Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Forest Carbon Sequestration and Spatial Heterogeneity of Influencing Factors: Evidence from the Beiluo River Basin in the Loess Plateau, China. Forests 2025, 16, 1719. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111719

Dong L, Li H, Deng Y, Wu H, Khan HS. Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Forest Carbon Sequestration and Spatial Heterogeneity of Influencing Factors: Evidence from the Beiluo River Basin in the Loess Plateau, China. Forests. 2025; 16(11):1719. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111719

Chicago/Turabian StyleDong, Lin, Hua Li, Yuanjie Deng, Hao Wu, and Hassan Saif Khan. 2025. "Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Forest Carbon Sequestration and Spatial Heterogeneity of Influencing Factors: Evidence from the Beiluo River Basin in the Loess Plateau, China" Forests 16, no. 11: 1719. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111719

APA StyleDong, L., Li, H., Deng, Y., Wu, H., & Khan, H. S. (2025). Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Forest Carbon Sequestration and Spatial Heterogeneity of Influencing Factors: Evidence from the Beiluo River Basin in the Loess Plateau, China. Forests, 16(11), 1719. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111719