Abstract

Fire refugia play an important role in post-fire ecosystem recovery because they preserve areas that represent a persistent legacy in the landscape and serve as propagule sources for forest regeneration. Our objective was to identify the pre-fire topographic and land cover conditions that determine the presence and quality of megafire refugia in the mountains of central Argentina. In 208 1-ha field-based plots, we assessed pre-fire topographic and land cover variables along with post-fire vegetation responses two years after the megafires. Based on these assessments, we developed a fire refugia quality index ranging from 0 (no refugia) to 5 (high-quality refugia). Using ordinal logistic regression and a model selection approach, we found that high-quality fire refugia were associated with the more humid east mountain flank and east- and north-facing slopes, as well as with smooth terrain, high topographic positions, greater rock cover, steep slopes, and higher tree-to-grass cover proportions. Our findings highlight the importance of topographic and land cover variables in shaping fire refugia and provide insights into post-fire management and the conservation of biodiversity in mountain ecosystems.

Keywords:

Argentina; forest regeneration; ecosystem recovery; Polylepis; sprouting; wildfire; shelter 1. Introduction

In recent decades, human-induced landscape and climate changes have led to an increase in extreme wildfires worldwide [1], posing major threats to human well-being, ecosystem services and vegetation resilience [2]. In burned landscapes, areas that remain unburned or are only partially affected, known as fire refugia, play a key role in post-fire recovery. These patches preserve biological legacies, serve as propagule sources for forest regeneration, and provide shelter and food for wildlife during and immediately after fires [3,4].

In subtropical mountain ecosystems, prolonged and intense dry seasons can reduce the number, size, and effectiveness of fire refugia by increasing fuel dryness and fire severity [5,6]. Under such conditions, fires tend to spread more evenly across the landscape, resulting in a decrease in unburned or less severely burned patches [7]. Nevertheless, fire refugia can still occur in areas where local environmental features create microclimates that mitigate fire intensity, or where non-combustible land covers, such as rocky areas, interrupt fuel continuity [3,8].

The formation of fire refugia is influenced by topographic and land cover features, which play a key role in burn severity and the direction of spread during the fire. Refugia often occur in sites with high soil moisture, such as valley bottoms, shaded slopes, or high elevations with reduced evapotranspiration [9,10,11]. They may also be formed on a rough or rocky terrain that disrupts fuel continuity and provides physical protection to vegetation. In contrast, vegetation structure can enhance or limit refugia formation; for example, tall forests with shaded understories embedded within flammable grasslands can reduce fire spread, increasing the likelihood of refugia persistence [12,13].

Specific combinations of topographic and land cover conditions tend to make fire refugia more predictable and persistent over time, since they consistently limit fire spread and allow certain areas to remain unburned through successive fire events [3,14]. Moreover, the persistence of refugia is influenced by feedbacks between fire and vegetation, because changes in fuel structure over time can either protect a site or increase its vulnerability to future fires. While some refugia remain permanently unburned and predictable, other refugia may be short-lived, playing their role during a single fire but becoming susceptible to burning under extreme fire conditions [3]. Moreover, plants adapted to subtropical climates generally have a strong post-fire resprouting capacity. Sprouts can emerge from roots, the trunk base, or lightly scorched stems, fueled mainly by starch reserves in the roots [15,16]. Therefore, when evaluating fire refugia, differences in post-fire negative effects on resprouting capacity should be considered. Even when the aboveground biomass is entirely burned, cryptic refugia may persist at sites where fire intensity was low. From these sites, forest recovery and wildlife refuge functions are likely to be restored sooner than in more severely affected areas.

Despite their ecological importance, fire refugia remain poorly studied in many subtropical regions with an extended dry season. In the subtropical mountain forests of central Argentina, post-fire survival of trees depends on several factors that presumably explain the current distribution of forests. These factors include fire intensity, influenced by topography, rock outcrops and biomass moisture content and fuel loads [17,18,19,20]. Nevertheless, no study has still comprehensively examined the topographic and land cover drivers of fire refugia formation at the landscape scale using field-based approaches.

Here, our aim is to identify the pre-fire conditions that determine the presence and quality of fire refugia during megafire conditions in the mountains of central Argentina. We hypothesize that the presence and quality of fire refugia are influenced by both topography and land cover. Specifically, we expect highest-quality fire refugia to occur in sites with the following characteristics: high elevations, steep slopes, high soil moisture due to low solar exposure (east and south facing slopes in the southern hemisphere), low topographic positions, high roughness, high rock cover, low tussock grass cover, and/or high tree cover. Understanding the key factors that allow certain sites to act as fire refugia will aid post-fire conservation and restoration efforts of these increasingly threatened mountain ecosystems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The mountains in central Argentina run north to south, ranging in elevation from 400 to 2789 m asl. In our study area in Cordoba province (lat −32.093, lon −64.844) the mountain range is characterized by asymmetrical flanks, with the western flank being steeper than the eastern flank (Figure 1). The climate varies with elevation: mean annual temperature decreases from 15.7 °C at 900 m to 7.4 °C at 2700 m asl, while annual precipitation increases from 600 mm at 600 m to 1000 mm at 2200 m asl [15]. Correspondingly, soil temperature decreases (r2 = −0.97) and soil moisture increases (r2 = 0.95) from lowlands to highlands [21]. The dry-cold season lasts from May to September and precipitations are concentrated in the warm months, from October to April [22].

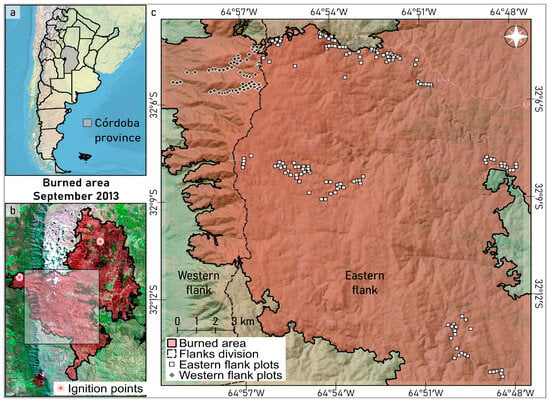

Figure 1.

(a) Location of the study area in Córdoba province and Argentina. (b) False color composite of satellite image (Landsat 8 OLI, bands 7/5/3, date 9 October 2013) of the burned area in September 2013. Ignition points; the square represents the distribution of the 208 study plots. (c) Distribution of the plots on both mountain flanks in the burned area.

The landscape comprises a mosaic of grasslands, bare soils, natural and anthropogenic exposed rock surfaces, shrublands and forests. Above 1700 m asl, forests are dominated by Polylepis australis, accompanied by Maytenus boaria and the shrub Escallonia cordobensis. Between 1700 and 1300 m asl, forests represent a transition to the Chaco Serrano ecosystem, while below 1300 m asl, within the Chaco Serrano ecosystem, forests are composed of tree species such as Lithraea molleoides, Celtis ehrenbergiana, Schinus fasciculata, Zanthoxylum coco, Kageneckia lanceolata and Schinopsis marginata [15]. The predominant post-fire regeneration strategy for native woody species in the region is resprouting [16,23,24].

The main economic activities in the region are extensive livestock rearing, tourism, and exotic pine plantations. Fires are predominantly fueled by tussock grasses, which become highly flammable during the dry season [25]. An average of about 3% of the area burns annually at intermediate elevations (900–1700 m asl) dominated by grasslands, and on average 1%–2% of the area burns annually at lower (<900 m asl) and higher (>1700 m asl) elevations, where woody vegetation and rock cover predominate, respectively [26]. Although lightning-ignited fires have been recorded, most fires are human-induced [26]. Current forest restoration efforts primarily focus on protecting areas from livestock grazing, planting the dominant tree species and cutting tussock grasses in an attempt to protect the restoration areas with fire-breaks (www.ecosistemasarg.org.ar, www.accionserrana.com, www.fundacionbosquizar.blogspot.com, www.bosquesdeagua.ar; (accessed on 27 June 2025)).

2.2. Study Fires

In September 2013, two fires, known locally as “Calamuchita 2013”, occurred simultaneously during six days, under meteorological conditions conducive to fire spread: wind speeds of up to 70 km·h−1, temperatures of 40 °C, and very low humidity (the fires occurred after a four-month period without precipitation). One fire started on the eastern flank, in Sol de Mayo village, and burned around 40 houses, killed thousands of livestock (sheep, goats, cattle), and consumed pine plantations that had high amounts of dead pines on the ground due to an intense windstorm of the previous year. The other ignition point, on the western flank, started in La Población village, and burned native grasslands and forests, and killed livestock. Both fires spread uphill and met near the mountain tops (Figure 1). The fires, which were characterized as highly intense crown fires, consumed most of the above-ground vegetation, spread over an elevation range of 700 to 2600 m asl, and burned 60,000 hectares (Figure 1). Due to their extraordinary size, the Calamuchita fires can be described as “megafires” [27].

2.3. Study Design

We selected 208 1-ha plots using pre-fire satellite imagery available on Google Earth. All plots were located within the boundaries of the burned area, in zones characterized by forest or sparse tree cover of at least 1%, distributed along four elevational transects ranging from 1039 to 2562 m asl and at least 60 m apart from the nearest plot to enhance spatial independence (mean nearest distance: 190 m, see Figure 1). Between June and December 2015, about two years after the fires, we located the plots in the field using GPS coordinates and detailed Google Earth printouts that helped match the plot boundaries with field landmarks such as rock outcrops and individual trees. Data were collected by visiting the plots and trees within, but also by estimating cover variables with binoculars from vantage points 30–100 m away, usually on the opposite slope. To ensure consistency, all visual estimations were made by the same observer (RS) after a training period.

2.4. Topographic and Land Cover Variables

The topographic variables recorded in the field to characterize each plot included: mountain flank (east or west), slope aspect of the plot in degrees from north and slope inclination in degrees (Table 1). To further characterize the slope aspect of the plot, we calculated northness and westness using cosine and the inverse of sine (i.e., −1 × sine) transformations. Northness represents annual insolation, while westness indicates exposure to solar radiation during the hottest part of the day. To complement the field-collected topographic data, we performed Geographic Information System (GIS) processes based on a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) using the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission (SRTM, 30 m/px) to derive additional variables: topographic position index, roughness index, and elevation (m asl; Table 1). The topographic position was calculated within a 315-m radius buffer using Equation (1):

Table 1.

Description of plot topographic and land cover variables used as explanatory variables. Indexes are dimensionless.

The index ranges from 0 to 1 (indicating the lowest and highest position, respectively, in relation to the surrounding landscape). The roughness index was calculated using the Geospatial Data Abstraction Library (GDAL) terrain roughness algorithm, which determines the differences in elevation among neighboring pixels [28]. We used the average value of the nine pixels surrounding the plot center. All GIS processes were conducted in QGIS (version 3.22 Białowieża).

The land cover variables were all recorded in the field and consisted of proportion of herbaceous vegetation (grasses and forbs), woody vegetation (trees and shrubs), and rocks (outcrops or pavements). Additionally, for a sample of up to 20 trees per plot (2336 in total), we identified the species and estimated the pre-fire tree height as well as the rock cover (%) under the tree crown. Although all field data were collected two years after the fires, we estimated pre-fire values based on the regrowth of herbaceous vegetation and the remaining standing stems, which typically persist for several years following fire events. To synthesize land-cover information, we created three additional variables representing proportions between pairs of cover types. The grass–rock proportion ranges from 0 (100% rock cover) to 1 (100% grass cover) and was calculated as (2):

Using the same approach, we calculated the tree–grass proportion and the tree–rock proportion. For the individual tree measurements, we calculated the maximum and mean tree height per plot, and the average of rock cover under the crowns for each plot (Table 1).

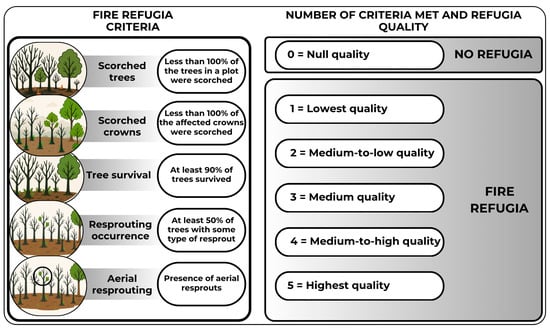

2.5. Refugia Quality Score as Dependent Variable

To create a fire refugia quality score, we assessed the following variables (related to fire effects and post-fire vegetation response) for each plot: proportion of tree cover that was scorched (%); proportion of scorched crown of fire-affected trees, averaged per plot (%); post-fire survival (%); post-fire proportion of resprouted trees (%) and presence of aerial resprouts (from the branches or trunks). a binary value of 1 or 0 was assigned to each plot for each variable if it met (or did not meet, respectively) the following specific criteria: (a) scorched trees: less than 100% of the trees in a plot were scorched; (b) scorched crowns: less than 100% on average of tree crowns were scorched; (c) tree survival: at least 90% of trees survived; (d) resprouting occurrence: at least 50% of trees exhibited some type of post-fire resprouting, including basal and aerial resprouting; (e) aerial resprouting: presence of sprouts in branches or trunks. Finally, the met criteria were summed for each plot in order to build a refugia quality score ranging from 0 (no refugia) to 5 (highest quality fire refugia). Refugia criteria and quality score are graphically summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Criteria used to define fire refugia and number of criteria required for each assigned refugia quality score. The circle at the lower-left indicates the drawn aerial sprouts.

2.6. Data Analysis

We performed ordinal logistic regression (proportional odds model) using the function polr from the MASS package in R [29] to identify the variables that best explained the quality of a plot as fire refugia. The response variable was the quality score (ranging from 0 to 5), treated as an ordered factor. The model assumes an underlying continuous latent variable with a logistic-distributed error (proportional odds assumption).

The explanatory variables included in the analysis were either topographic or related to land cover. The mountain flank (east or west) was considered as a fixed/control factor, since both flanks experienced different ignition events, and the west flank was steeper than the east flank. We considered the following continuous variables: elevation, northness, westness, slope, topographic position, roughness, tree, grass, and rock covers, grass–rock, tree–grass, and tree–rock proportions; maximum and mean pre-fire tree height; and average rock cover under the tree crowns (Table 1). We also included the transect (1 to 4) as a random effect to account for spatial clustering within each hydrographic basin. Before modeling, we evaluated pairwise correlations among explanatory variables.

We applied an automatic forward stepwise algorithm from the MASS package to identify the combination of explanatory variables that minimized the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). However, at any step, if the procedure selected a variable that was moderately or highly correlated (|r| ≥ 0.5) with another variable that was already included, we discarded it and restarted the process. This was repeated until a set of uncorrelated or only slightly correlated variables was obtained. This approach was adopted to avoid redundancy and multicollinearity and to facilitate the interpretation of results. The AIC was chosen because it provides a robust balance between model fit and complexity, penalizing the inclusion of unnecessary parameters and thus helping to avoid over-fitting.

Model residuals were manually computed following the approach implemented in the DHARMa package [30], since this package does not directly support polr models. We then conducted standard diagnostic checks, including assessment of the residual distribution (expected to be uniform), overdispersion, and potential relationships with fitted values and with each predictor variable. No significant biases or violations of model assumptions were detected. Spatial autocorrelation was tested using the Mantel approach to evaluate whether model residuals were spatially structured. All statistical analyses were conducted in R (version 3.4.2; [31]), and results were considered statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05. However, we also interpreted, with caution, the non-significant variables included in the model by our selection procedure, because according to the AIC criteria, they were informative, and their p-values were relatively low (i.e., <0.15, see results).

3. Results

3.1. Fire Refugia Quality

All 208 study plots were partially or completely burned. Twenty-seven plots (13%) did not meet any of the five criteria used to define fire refugia quality (Figure 2). Fire refugia of low and medium-to-low quality (refugia meeting one or two criteria, respectively), were identified in 20 (10%) and 47 (22%) of the plots, respectively. Most refugia (62 plots, 30%) met three criteria and were classified as intermediate quality. Higher-quality refugia were less frequent: 38 plots (18%) met four criteria (medium-to-high quality), and only 14 (7%) met all five criteria (high quality). The frequency of each criterion met is summarized in Table S1.

3.2. Topographic and Land Cover Effects

The slopes of the plots were oriented in all directions, with the plots on the eastern flank of the mountain predominantly, but not exclusively, facing north and east, while those on the western flank predominantly facing south and west. Elevation ranged from 1039 to 2562 m asl, with comparable variation on both flanks. Slope varied from 3 to 60°, showing an identical range on both mountain flanks. Likewise, the plots on both flanks had similar ranges in terms of topographic position and roughness (Table S2).

In terms of land cover, rock cover ranged from 1% to 92% on the eastern flank, and up to 70% on the western flank. Grass cover generally ranged from 5% to over 95%, with the minimum on the eastern flank being 17%. Tree cover varied between 1% and 80%, and was similarly distributed on both mountain flanks. Overall, the proportion of grass–rock, tree–grass, and tree–rock were comparable among both flanks. Tree height ranged from 1 to 10 m, and rock cover under tree crowns varied between 0% and ~77% (Table S2). Tree species exhibited a clear elevational distribution. Polylepis australis dominated the highest plots, while Escallonia cordobensis, Maytenus boaria, Schinus spp., and Lithraea molleoides appeared progressively toward lower elevations, though they were not necessarily dominant (Table S3).

The model that best explained fire refugia quality included the following variables, sorted by z-value (which reflects the strength and statistical significance of each predictor): mountain flank (east or west), roughness, plot westness, topographic position, rock cover, slope, tree–grass proportion and northness (pseudo R2 McFadden = 0.165; Table 2). No spatial autocorrelation was detected in the model residuals, as evidenced by the semivariogram and confirmed statistically using a Mantel test (r = −0.061, p = 0.995).

Table 2.

Results of the ordinal logistic regression model explaining fire refugia quality. The table reports estimated coefficients, standard errors, z-values, and p-values for each selected explanatory variable. The response variable is the fire refugia quality score. The model assumes an ordinal distribution and includes data from 208 plots. Mountain flank (east or west) is a categorical variable; all the other predictors are continuous. Variables are ordered by the absolute value of their z-statistic. Model AIC = 609.21.

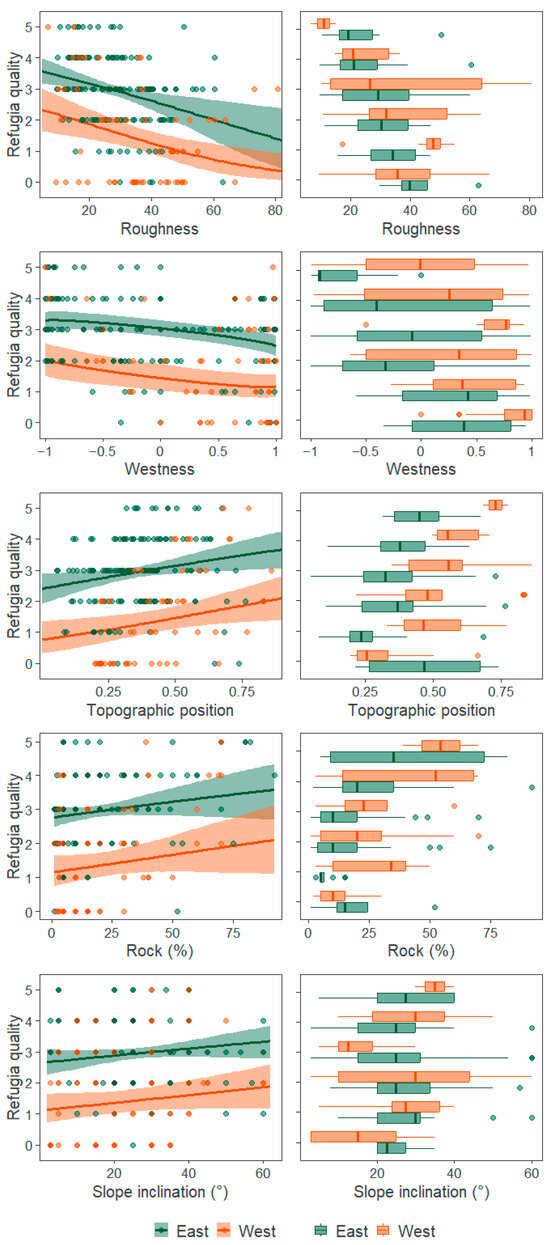

Mountain flank (east or west) had the highest absolute z-value, with high-quality refugia predominantly located on the eastern mountain flank, while plots that were not refugia or were of poor quality were mostly situated on the western flank of the mountain range. Refugia quality decreased with increasing roughness, with the higher quality of refugia more frequently found in areas with more homogeneous surfaces, and also decreased with the westness index, showing a pronounced contrast between no refugia and highest-quality refugia. Plots not characterized as refugia tended to be oriented towards the west, while the highest-quality refugia tended to be oriented towards the east, even in those east-facing slopes of the western flank. Plots that were not refugia were distributed across all topographic position types, with low topographic positions exhibiting the poorest refugia quality (Table S4 and Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Fire refugia quality, ranging from 0 (null quality or no refugia) to 5 (highest quality), as a function of mountain flank (east or west in green or orange, respectively) and the significant (p < 0.05) or nearly significant (p < 0.1) variables included in the model: roughness, westness, topographic position and rock cover. In the first column, model predictions are shown as continuous lines, representing the expected quality score (i.e., the average of the quality scores weighted by their predicted probabilities), with shaded areas representing 95% confidence intervals calculated through a bootstrap procedure. Circles denote observed data points. Curves were generated from the ordinal logistic regression model, with non-displayed covariates held at their mean values for each flank (Table S2), except for plot westness, where northness was allowed to vary consistently with westness. The second column shows boxplots of the observed data, according to each refugia quality category.

According to model predictions, the highest-quality fire refugia are located in areas with high rock cover, which generally coincide with higher elevations. Rock cover in the 14 plots with the highest-quality refugia ranged from 82 to 92%, while it never exceeded 50% in the categories “no refugia” and “lowest-quality refugia” (1 or 2 criteria met, Figure 3). The quality of refugia also increased slightly with increasing slope. Only plots that did not constitute fire refugia (i.e., did not meet any criteria) had slopes of less than 20°, while all refugia plots, regardless of their quality, had slopes ranging between 25 and 30°. The model showed that the tree–grass proportion slightly tended to increase refugia quality, indicating that higher-quality refugia tended to have greater tree cover than grass cover (Table S4 and Figure 3). Finally, northness was also included in the model, indicating that refugia quality slightly increases in north-facing slopes. Variables not included in the model were elevation, grass cover, tree cover, grass–rock proportion, tree–rock proportion, mean and maximum tree height, rock cover under the crown, and transect (Table S4). Although elevation showed a good predictive performance, it was removed due to its high collinearity with rock cover (r = 0.59).

4. Discussion

In landscapes increasingly exposed to high-intensity fires, the long-term persistence of forests may depend on the presence of the few remaining effective fire refugia. However, all our study plots were partially or completely burned, a situation that, to the best of our knowledge, represents the first such record in at least the past 30 years [15,20]. Interestingly, three of the eight selected variables explaining refugia quality exhibited patterns contrary to our expectations based on previous studies, suggesting that megafires are not only more intense and larger, but also different. The high wind speeds, high temperatures, and a four-month drought, likely shifted the influence of factors that normally shape fire behavior [32,33]. Consequently, the projected increase in extreme wildfire events begs for further studies on the formation of fire refugia [1]. Nonetheless, our first findings highlight the central role of topography and, to a lesser extent of land cover, in determining the occurrence and quality of fire refugia following megafires.

4.1. Topographic Influences

Fire refugia quality was best explained by mountain flank, possibly due to greater rainfall, lower temperatures [34], and reduced fuel loads from higher livestock densities on the eastern flank [20,35]. Surface roughness ranked second but, unexpectedly, refugia were more frequent in smoother terrain. The reasons for this unexpected result are unclear and need more research; perhaps fires passed faster in smoother terrain due to high wind speeds not slowed down by surface roughness, but could also be due to grazing pressure. Smoother terrain is usually associated with high grazing pressure, which maintains extremely short lawns that are not burnt [20,36]. Westness emerged as the third strongest predictor, with east-facing slopes likely experiencing less intense fires due to reduced afternoon sun exposure, and the consequent reduced evaporation compared to west-facing slopes. This supports the expected pattern and reinforces the importance of mountain flank as the primary predictor, since higher-quality refugia were associated with the east flank and, within both flanks, with more east-facing slopes.

Topographic position was fourth, but, again, contrary to expectations: refugia quality increased at higher topographic positions. This finding disagrees with studies of previous fires that report a lower fire frequency in deep ravines attributed to higher humidity and better protection against fire spread ([15,20] and literature cited therein), but is in agreement with a previous study reporting significant canopy damage in a ravine during the Calamuchita 2013 fires [23], highlighting the atypical behavior of these events. A possible explanation is that ravines and valleys may act as wind corridors under extreme fire conditions and can intensify fire severity rather than provide protection, as described by Povak et al. [10] for Bailey’s ecoregion in California, USA.

Slope inclination and northness ranked sixth and eighth in importance, and were the only topographic features that were less important than a land cover feature in explaining fire refugia. Presumably, fire spreads more quickly on steep slopes, with the consequent reduction in vegetation exposure to flames and, consequently, producing less damage to vegetation [37]. Unexpectedly, higher-quality refugia were found in north-facing slopes (although with a p-value of 0.15), which are more sun exposed and drier than south-facing slopes. In other regions, unburned islands or low-severity fires are found more often on poleward-facing slopes [20,38,39,40], but exceptions have also been reported and attributed to wetter soils accumulating more biomass when not grazed, and becoming vulnerable to fire under extreme conditions [41]. Since soil moisture–grazing interactions were not evaluated, our proposed explanations remain tentative, and partly contradictory when comparing the explanations for northness and westness.

4.2. Land Cover

Given the large heterogeneity in rock cover in the mountain ranges studied and the evident role of rock in reducing fire-induced damage to vegetation [15], it is not surprising that rock cover emerged as a factor influencing refugia quality, albeit only in the fifth place. Rocks create discontinuities in flammable fuel, thereby preventing fire spread. Therefore, rock cover should serve as an important protective barrier for shrubs and trees against surface fires, ultimately enhancing fire refugia quality. The association between rock cover under the crown and the proportion of scorched crown has already been documented for P. australis trees and forest stands in our study area, as well as for other species [15,20]. However, this is the first time that rock cover has been identified as a fire protection mechanism on a large scale (1-ha plots) and in association with other species such as M. boaria and E. cordobensis. The role of rock surfaces in the upper part of the mountains as barriers to the spread of fire was discussed, but not measured, by Argañaraz et al. [26], who suggest that rock cover limits the total extension of each fire and as a consequence the total annual burned area compared with intermediate elevations where rock surfaces occupy a far lower proportion of the area.

The tree–grass cover proportion was of lower statistical importance, even when it presented an important trend with fire-refugia quality. This said, tree–grass cover proportion was the only explanatory variable that can be manipulated through forest restoration or deforestation actions; therefore, it is especially important in management. Tree canopies reduce insolation and limit the growth of grasses beneath them, especially fine and continuous fuels, thereby acting as a physical barrier to fire spread [17,18]. In contrast, sites with high grass cover have fine and continuous accumulated fuels that facilitate fire propagation. However, repeated fires with short return intervals can disrupt this protective structure by preventing trees from reaching maturity, which reduces canopy cover and leads to increased fuel accumulation on the ground, a shift that increases grass dominance and fire susceptibility [18,20]. Therefore, efforts to maintain or enhance tree cover relative to grasses, particularly through the promotion of native tree species with higher fire resistance and resprouting capacity, may help to increase the persistence and spatial extent of future fire refugia and strengthen the landscape’s resilience to fire.

4.3. Obstacles, Limitations and Future Research

Our first study of fire refugia in subtropical mountains needs further replications to determine which predictors remain stable along successive megafire events, which have continued to occur after the fire examined in this study [20]. The need for further replication is emphasized by some of our predictors did not reach statistical significance, and the difficulty in explaining some of our results. We suggest that future studies could improve on ours by evaluating pre-fire fuel accumulation, soil and vegetation moisture, and livestock preferences, which we hypothesize may be explaining several of the unexpected associations we found in this study. We urge for more efforts of this type, even when adapting research agendas to stochastic fire events is challenging, and pre-fire soil moisture and livestock use will be difficult to evaluate. The way forward may be combining high-resolution remote sensing, field experiments and/or well-controlled comparisons of different livestock management regimes, and long-term monitoring to have a better understanding of these factors.

5. Conclusions

Our first assessment of fire refugia showed that they were formed in the more humid east mountain flank and east-facing slopes, as well as in smooth terrain at high topographic positions. They also tended to be associated with areas with greater rock cover and steep slopes and, to a lesser extent, with areas with higher tree-to-grass cover proportions and north-facing slopes. These findings can help inform ongoing ecosystem restoration efforts. We suggest that the establishment of fire refugia should be added to the multiple factors that need to be taken into account when prioritizing areas for forest restoration. Eastern flanks, steep slopes and high rock cover should be given priority for forest restoration. In the case of tree species with short-distance dispersal, active forest restoration should be considered, otherwise, passive restoration through a reduction in disturbances and monitoring effectiveness would be more cost-effective. Current fire refugia that still have isolated trees or forests do not require forest restoration efforts, unless they are invaded by exotic species [15]. However, they should be given priority for biodiversity conservation and as a seed source for post-fire recovery of surrounding areas.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/f16111705/s1, Table S1. Frequency of occurrence of each criterion across the 208 study plots; Table S2. The pre-fire characteristics of the 208 study plots split by mountain flank (east or west). Minimum, mean and maximum values are presented. Units of measurement are provided in Table 1; Table S3. Details of species elevational distribution and pre- and post-fire characterization; Table S4. Summary statistics of measured explanatory variables split by refugia quality category.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and funding acquisition, D.R. and I.H.; investigation, R.S., D.S.A. and D.R.; formal analysis and interpretation of data, D.S.A., A.M.C. and J.S.; writing—review and editing, D.S.A., A.M.C., D.R., J.S., I.H. and R.S.; project administration and supervision, D.R. and I.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG-Germany; HE3041/21-1) and Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas (CONICET-Argentina; 11220170100143C).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article are available at https://datosdeinvestigacion.conicet.gov.ar/handle/11336/268571 (accessed on 2 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

Mateo Fuhr, Julia Meneghelo and Leandro García helped during data collection. Henrik von Wehrden helped in project elaboration and funding acquisition during his stay in Argentina.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest and the funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| GIS | Geographic Information System |

| GDAL | Geospatial Data Abstraction Library |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| m asl | Meters above sea level |

| SRTM | Shuttle Radar Topography Mission |

References

- Tedim, F.; Leone, V.; Amraoui, M.; Bouillon, C.; Coughlan, M.; Delogu, G.; Fernandes, P.; Ferreira, C.; McCaffrey, S.; McGee, T.; et al. Defining Extreme Wildfire Events: Difficulties, Challenges, and Impacts. Fire 2018, 1, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syphard, A.D.; Brennan, T.J.; Keeley, J.E. Extent and Drivers of Vegetation Type Conversion in Southern California Chaparral. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meddens, A.J.H.; Kolden, C.A.; Lutz, J.A.; Smith, A.M.S.; Cansler, C.A.; Abatzoglou, J.T.; Meigs, G.W.; Downing, W.M.; Krawchuk, M.A. Fire Refugia: What Are They, and Why Do They Matter for Global Change? BioScience 2018, 68, 944–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coop, J.D.; DeLory, T.J.; Downing, W.M.; Haire, S.L.; Krawchuk, M.A.; Miller, C.; Parisien, M.; Walker, R.B. Contributions of Fire Refugia to Resilient Ponderosa Pine and Dry Mixed-conifer Forest Landscapes. Ecosphere 2019, 10, e02809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawchuk, M.A.; Haire, S.L.; Coop, J.; Parisien, M.; Whitman, E.; Chong, G.; Miller, C. Topographic and Fire Weather Controls of Fire Refugia in Forested Ecosystems of Northwestern North America. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, S.U.; Holz, A. Interactions Between Fire Refugia and Climate-Environment Conditions Determine Mesic Subalpine Forest Recovery After Large and Severe Wildfires. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 890893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiribelli, F.; Paritsis, J.; Barberá, I.; Kitzberger, T. Spatial and Temporal Opportunities for Forest Resilience Promoted by Burn Severity Attenuation across a Productivity Gradient in North Western Patagonia. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2024, 33, WF23098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landesmann, J.B.; Morales, J.M. The Importance of Fire Refugia in the Recolonization of a Fire-Sensitive Conifer in Northern Patagonia. Plant Ecol. 2018, 219, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estes, B.L.; Knapp, E.E.; Skinner, C.N.; Miller, J.D.; Preisler, H.K. Factors Influencing Fire Severity under Moderate Burning Conditions in the Klamath Mountains, Northern California, USA. Ecosphere 2017, 8, e01794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Povak, N.A.; Hessburg, P.F.; Salter, R.B. Evidence for Scale-dependent Topographic Controls on Wildfire Spread. Ecosphere 2018, 9, e02443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tito, R.; Vasconcelos, H.L.; Feeley, K.J. Mountain Ecosystems as Natural Laboratories for Climate Change Experiments. Front. For. Glob. Change 2020, 3, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Schwilk, D.W. Burn Hot or Tolerate Trees: Flammability Decreases with Shade Tolerance in Grasses. Oikos 2022, 2022, e08930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelluti, O.; Elia, M.; Sanesi, G. Could Different Structural Features Affect Flammability Traits in Mediterranean Forest Ecosystems? Trees 2024, 38, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodman, K.C.; Davis, K.T.; Parks, S.A.; Chapman, T.B.; Coop, J.D.; Iniguez, J.M.; Roccaforte, J.P.; Sánchez Meador, A.J.; Springer, J.D.; Stevens-Rumann, C.S.; et al. Refuge-yeah or Refuge-nah? Predicting Locations of Forest Resistance and Recruitment in a Fiery World. Glob. Change Biol. 2023, 29, 7029–7050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cingolani, A.M.; Giorgis, M.A.; Hoyos, L.E.; Cabido, M. La vegetación de las montañas de Córdoba (Argentina) a comienzos del siglo XXI: Un mapa base para el ordenamiento territorial. Boletín Soc. Argent. Botánica 2022, 57, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaureguiberry, P.; Cuchietti, A.; Gorné, L.D.; Bertone, G.A.; Díaz, S. Post-Fire Resprouting Capacity of Seasonally Dry Forest Species—Two Quantitative Indices. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 473, 118267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaureguiberry, P.; Bertone, G.; Díaz, S. Device for the Standard Measurement of Shoot Flammability in the Field: Flammability Measurement in the Field. Austral Ecol. 2011, 36, 821–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowaljow, E.; Morales, M.S.; Whitworth-Hulse, J.I.; Zeballos, S.R.; Giorgis, M.A.; Rodríguez Catón, M.; Gurvich, D.E. A 55-year-old Natural Experiment Gives Evidence of the Effects of Changes in Fire Frequency on Ecosystem Properties in a Seasonal Subtropical Dry Forest. Land Degrad. Dev. 2019, 30, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argañaraz, J.P.; Radeloff, V.C.; Bar-Massada, A.; Gavier-Pizarro, G.I.; Scavuzzo, C.M.; Bellis, L.M. Assessing Wildfire Exposure in the Wildland-Urban Interface Area of the Mountains of Central Argentina. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 196, 499–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renison, D.; Barberá, I.; Cingolani, A.M.; Rodriguez, J.M.; Hensen, I. Tree Survival and Growth in the Highlands of Central Argentina: Impact of Wildfires and Land Management. For. Ecol. Manag. 2025, 589, 122773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais-Bosch, A.; Tecco, P.A.; Funes, G.; Cabido, M. Efecto de la temperatura en la regeneración de especies leñosas del chaco serrano e implicancias en la distribución actual y potencial de bosques. Boletín Soc. Argent. Botánica 2012, 47, 401–410. [Google Scholar]

- Colladon, L. Anuario Pluviométrico 1992/93–2011/12, Cuenca Del Río San Antonio. In Sistema Del Río Suquía—Provincia de Córdoba; Instituto Nacional del Agua y Centro de Investigaciones de la Región Semiárida (CIRSA): Córdoba, Argentina, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Argibay, D.S.; Renison, D. Efecto del fuego y la ganadería en bosques de Polylepis australis (Rosaceae) a lo largo de un gradiente altitudinal en las montañas del centro de la Argentina. Bosque 2018, 39, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, R.C.; Giorgis, M.A.; Trillo, C.; Volkmann, L.; Demaio, P.; Heredia, J.; Renison, D. Post-Fire Recovery Occurs Overwhelmingly by Resprouting in the Chaco Serrano Forest of Central Argentina: Post-Fire Tree Regeneration. Austral Ecol. 2014, 39, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argañaraz, J.P.; Landi, M.A.; Scavuzzo, C.M.; Bellis, L.M. Determining Fuel Moisture Thresholds to Assess Wildfire Hazard: A Contribution to an Operational Early Warning System. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argañaraz, J.P.; Cingolani, A.M.; Bellis, L.M.; Giorgis, M. Incidencia Del Fuego en Un Gradiente Altitudinal de Las Sierras Del Centro de la Argentina. Ecol. Austral 2020, 30, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linley, G.D.; Jolly, C.J.; Doherty, T.S.; Geary, W.L.; Armenteras, D.; Belcher, C.M.; Bliege Bird, R.; Duane, A.; Fletcher, M.; Giorgis, M.A.; et al. What Do You Mean, ‘Megafire’? Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2022, 31, 1906–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GDAL/OGR Contributors. GDAL/OGR Geospatial Data Abstraction Software Library 2023; Open Source Geospatial Foundation: Beaverton, OR, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ripley, B.; Venables, B.; Bates, D.M.; Hornik, K.; Gebhardt, A.; Firth, D.; Ripley, M.B. Package ‘MASS’. CRAN R 2013, 538, 822. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig, F. DHARMa: Residual Diagnostics for Hierarchical (Multi-Level/Mixed) Regression Models; R Package, Version 0.4.7 (2022) 2025; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, S.W.J.; Bennett, A.F.; Clarke, M.F. Determinants of the Occurrence of Unburnt Forest Patches: Potential Biotic Refuges within a Large, Intense Wildfire in South-Eastern Australia. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 314, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, L.; Bennett, A.F.; Leonard, S.W.J.; Penman, T.D. Wildfire Refugia in Forests: Severe Fire Weather and Drought Mute the Influence of Topography and Fuel Age. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 3829–3843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karger, D.N.; Conrad, O.; Böhner, J.; Kawohl, T.; Kreft, H.; Soria-Auza, R.W.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Linder, H.P.; Kessler, M. Climatologies at High Resolution for the Earth’s Land Surface Areas. Sci. Data 2017, 4, 170122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, R.E.; Staal, A.; Xu, C.; Scheffer, M.; Holmgren, M. Livestock Herbivory Shapes Fire Regimes and Vegetation Structure Across the Global Tropics. Ecosystems 2019, 22, 1457–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Müller, A.R.; Renison, D.; Cingolani, A.M. Cattle Landscape Selectivity Is Influenced by Ecological and Management Factors in a Heterogeneous Mountain Rangeland. Rangel. J. 2017, 39, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvani, X.; Morandini, F.; Dupuy, J.-L. Effects of Slope on Fire Spread Observed through Video Images and Multiple-Point Thermal Measurements. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2012, 41, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.D.; Seavy, N.E.; Ralph, C.J.; Hogoboom, B. Vegetation and Topographical Correlates of Fire Severity from Two Fires in the Klamath-Siskiyou Region of Oregon and California. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2006, 15, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Cuesta, R.M.; Gracia, M.; Retana, J. Factors Influencing the Formation of Unburned Forest Islands within the Perimeter of a Large Forest Fire. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.; Taylor, C.; Blanchard, W. Empirical Analyses of the Factors Influencing Fire Severity in Southeastern Australia. Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollins, M.G.; Morgan, P.; Swetnam, T. Landscape-Scale Controls over 20th Century FIre Occurrence in Two Large Rocky Mountain (USA) Wilderness Areas. Landsc. Ecol. 2002, 17, 539–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).