Morphological Plasticity of Ectomycorrhizal Symbiosis Promotes Adaptation of Faxon Fir (Abies fargesii var. faxoniana) to Altitudinal and Environmental Changes on Eastern Qinghai–Tibet Plateau

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Sites

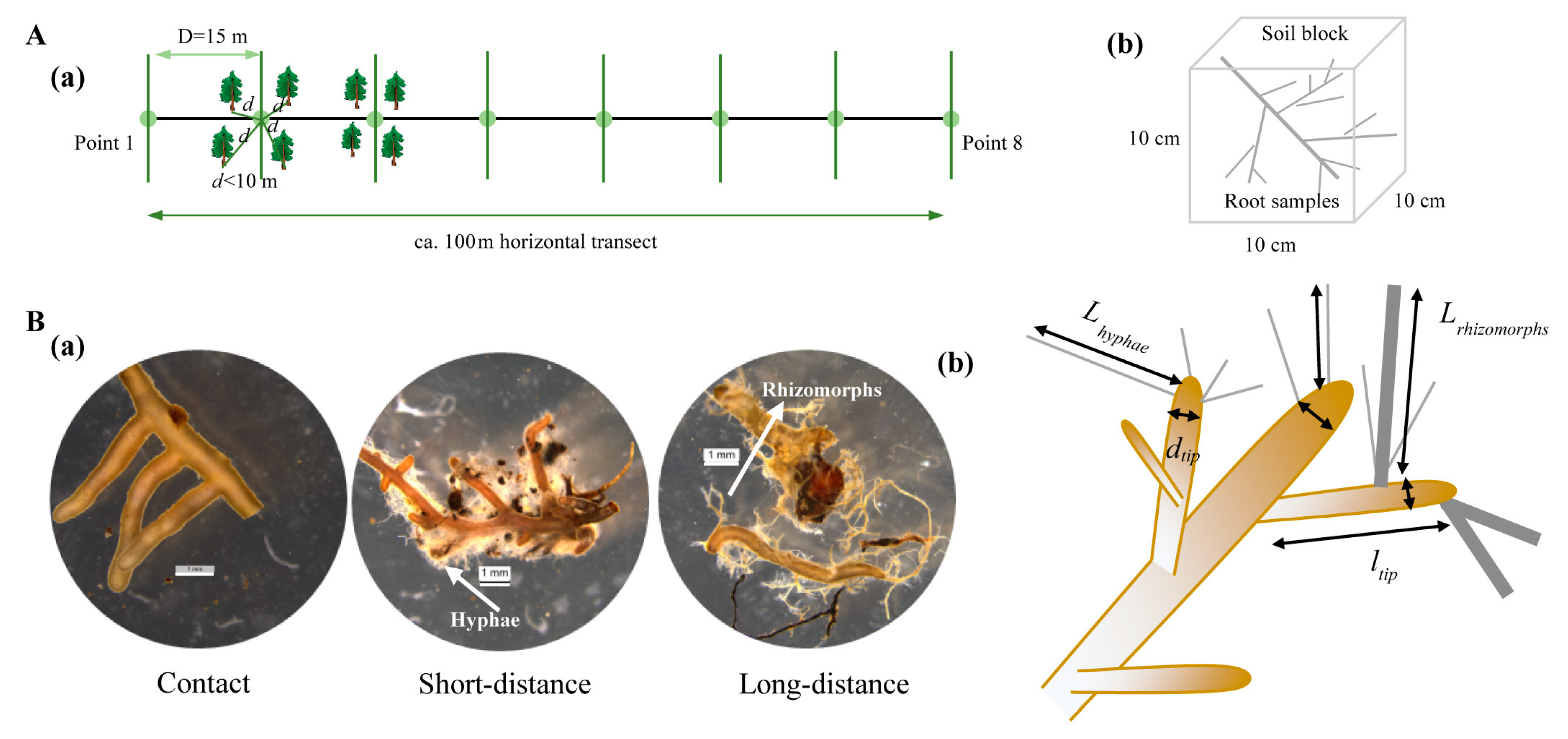

2.2. Field Sampling and Processing

2.3. Classification and Measurements of ECM Root Traits

2.4. Plant and Soil Chemistry

2.5. Climatic Data

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

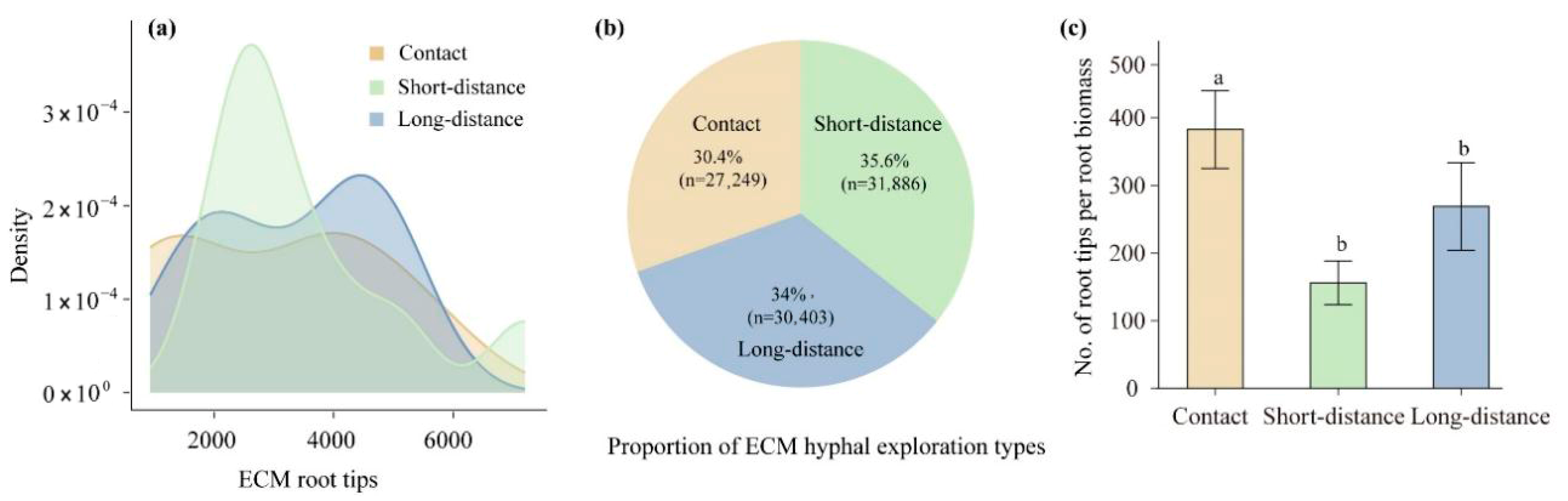

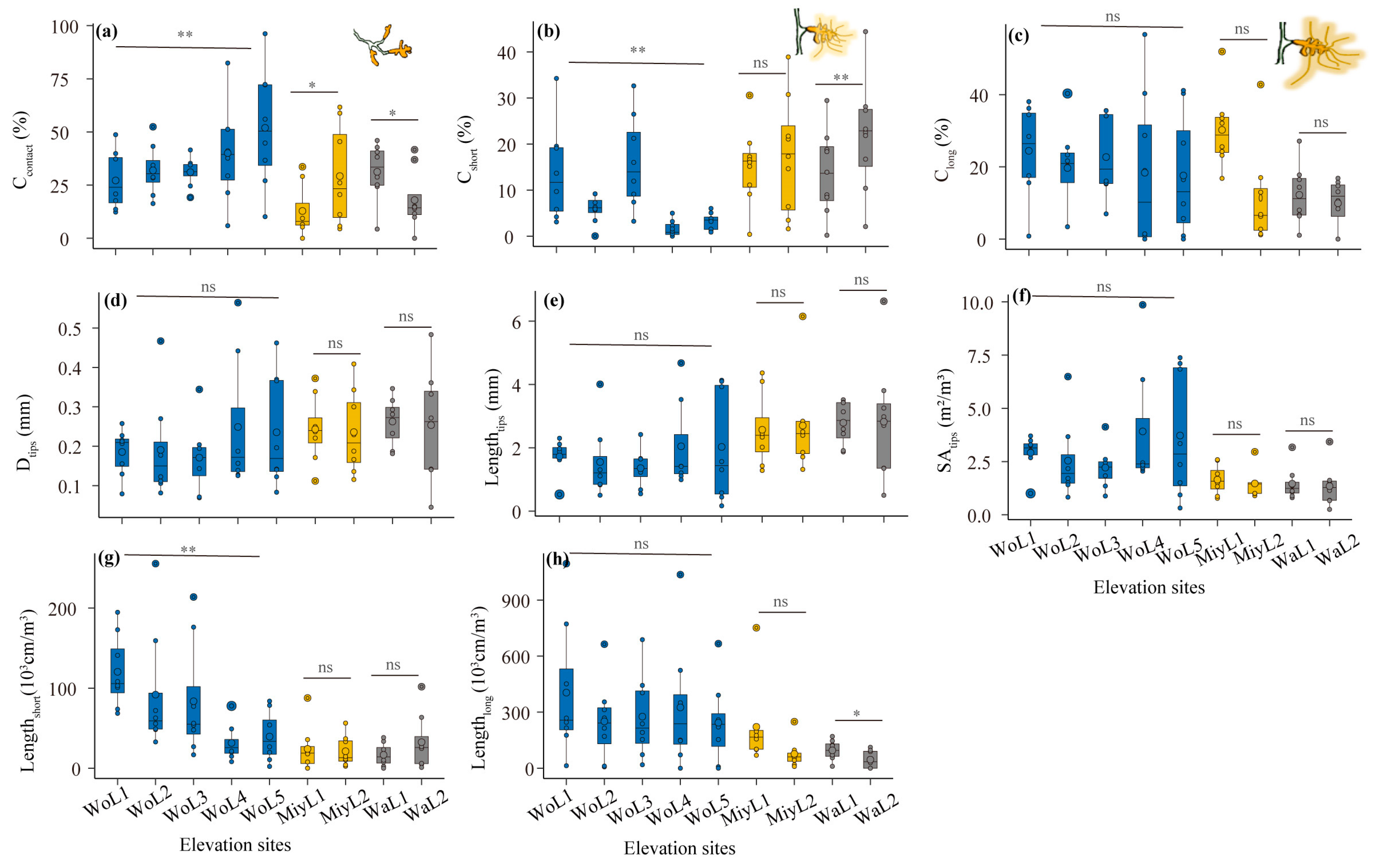

3.1. Morphological Traits of ECM Associations in Changing Environments

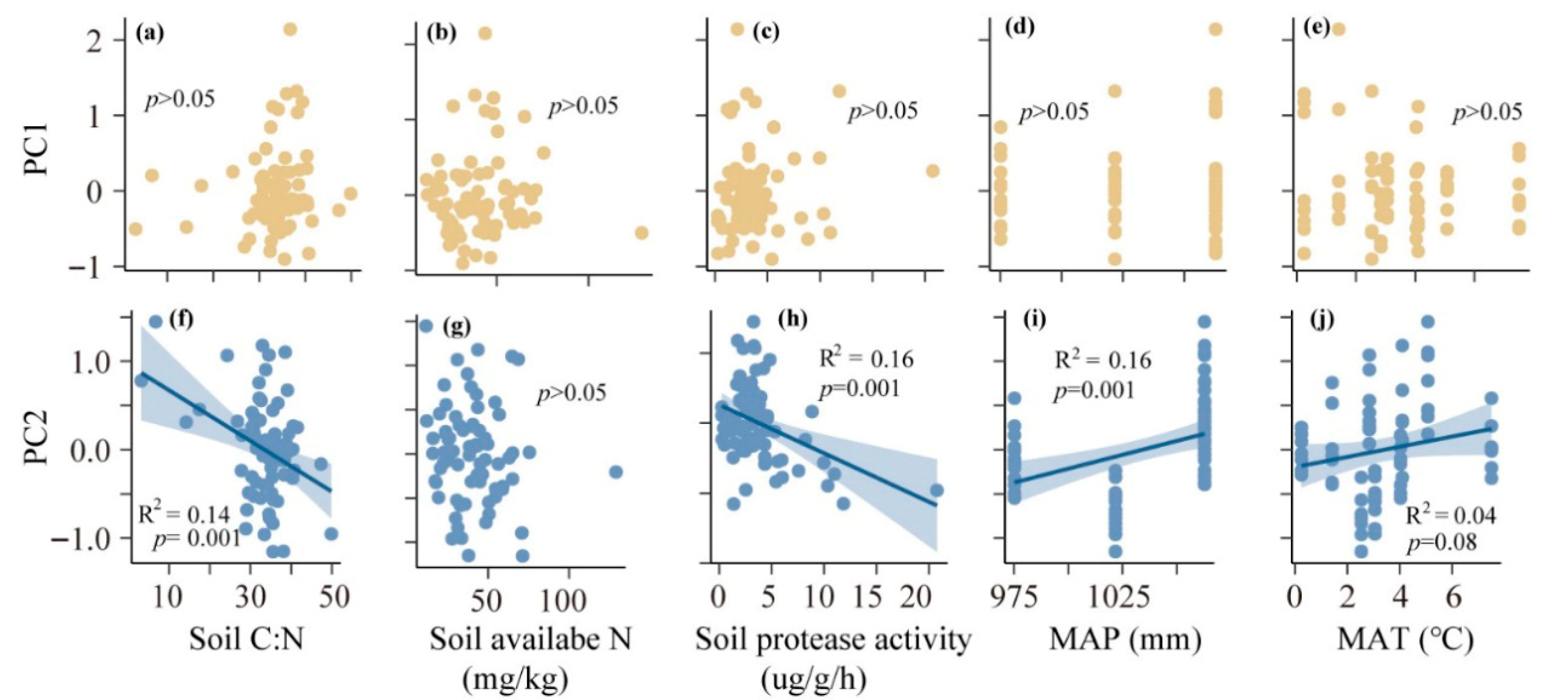

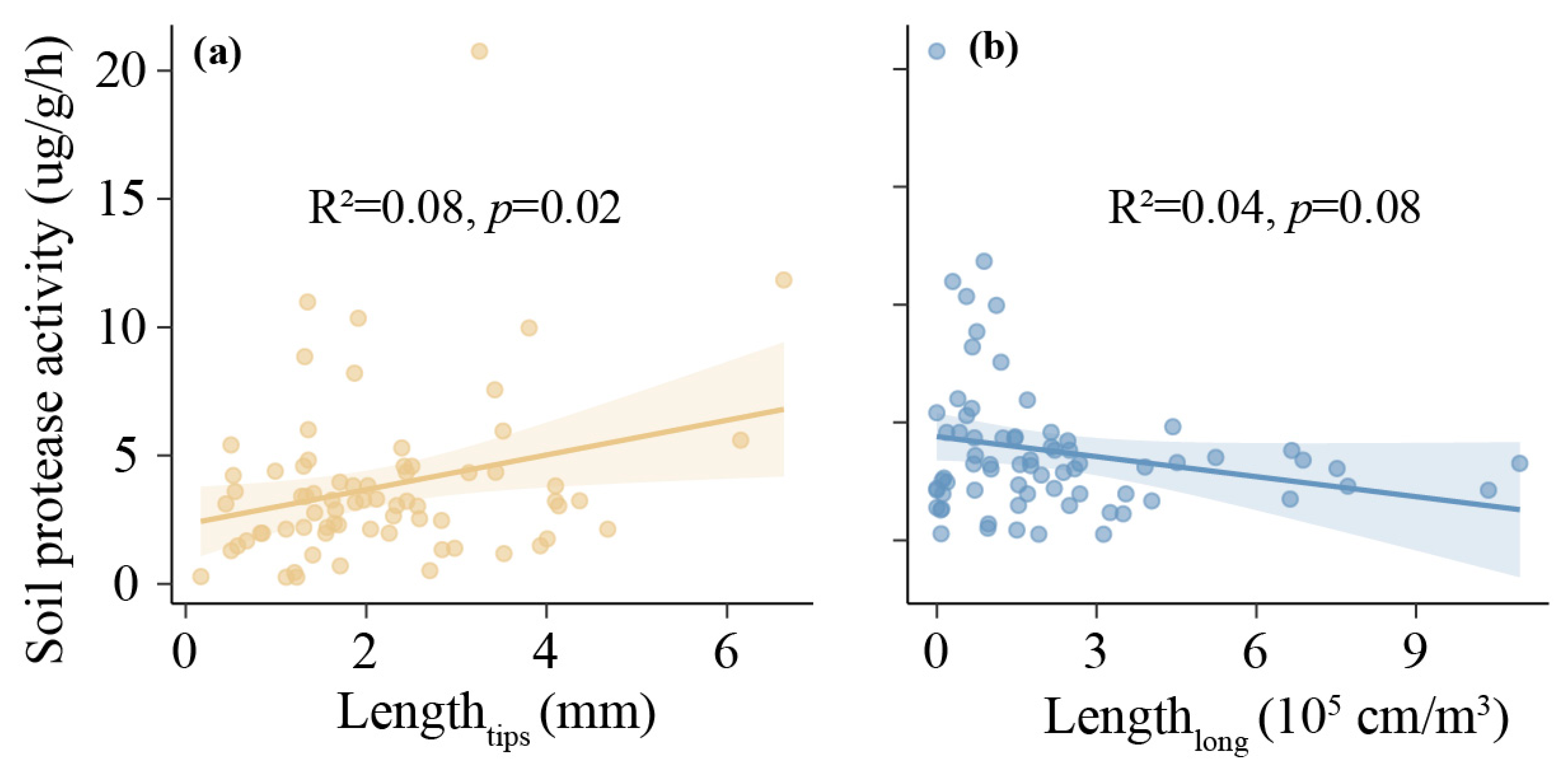

3.2. Effects of Environmental Factors on ECM Morphological Traits

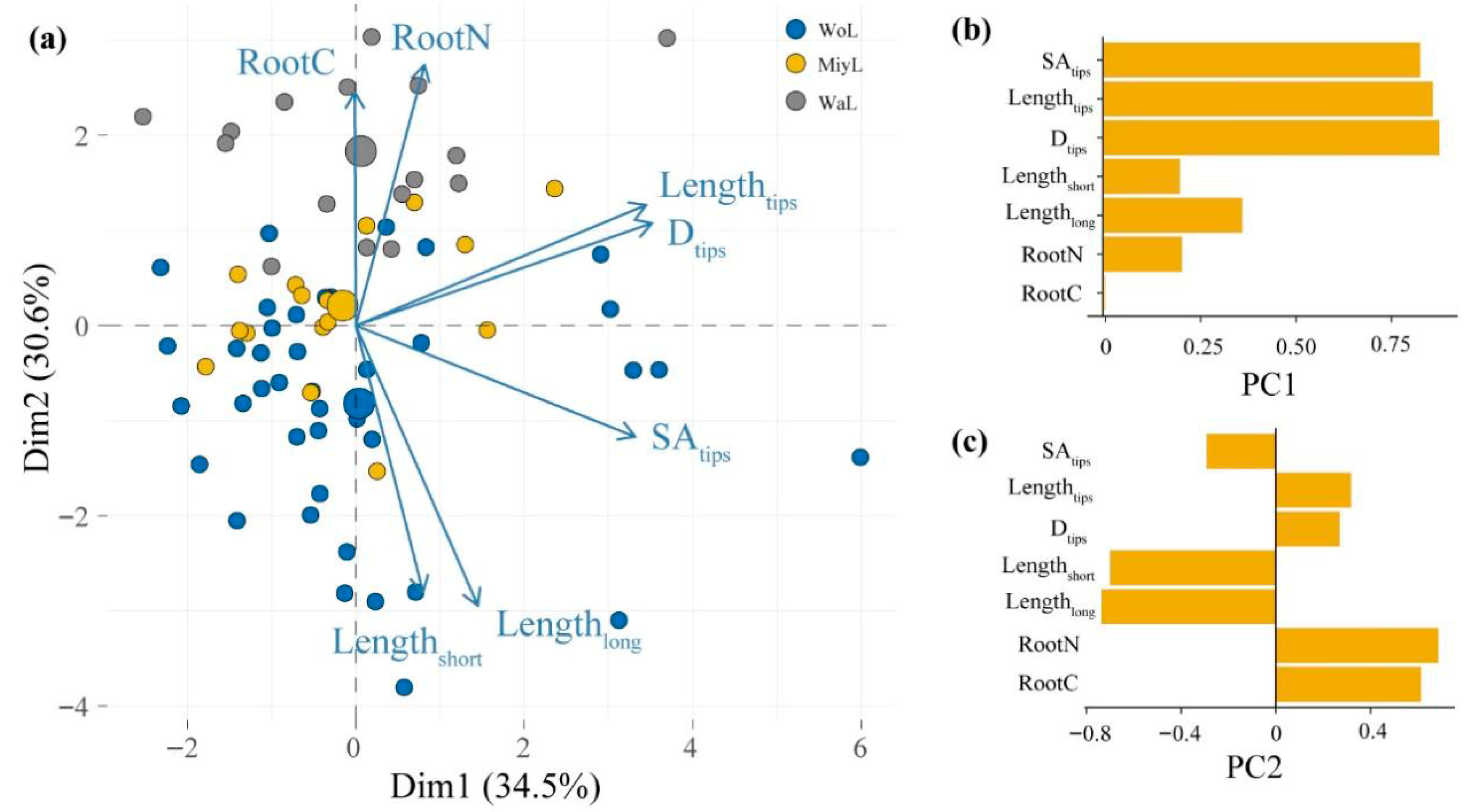

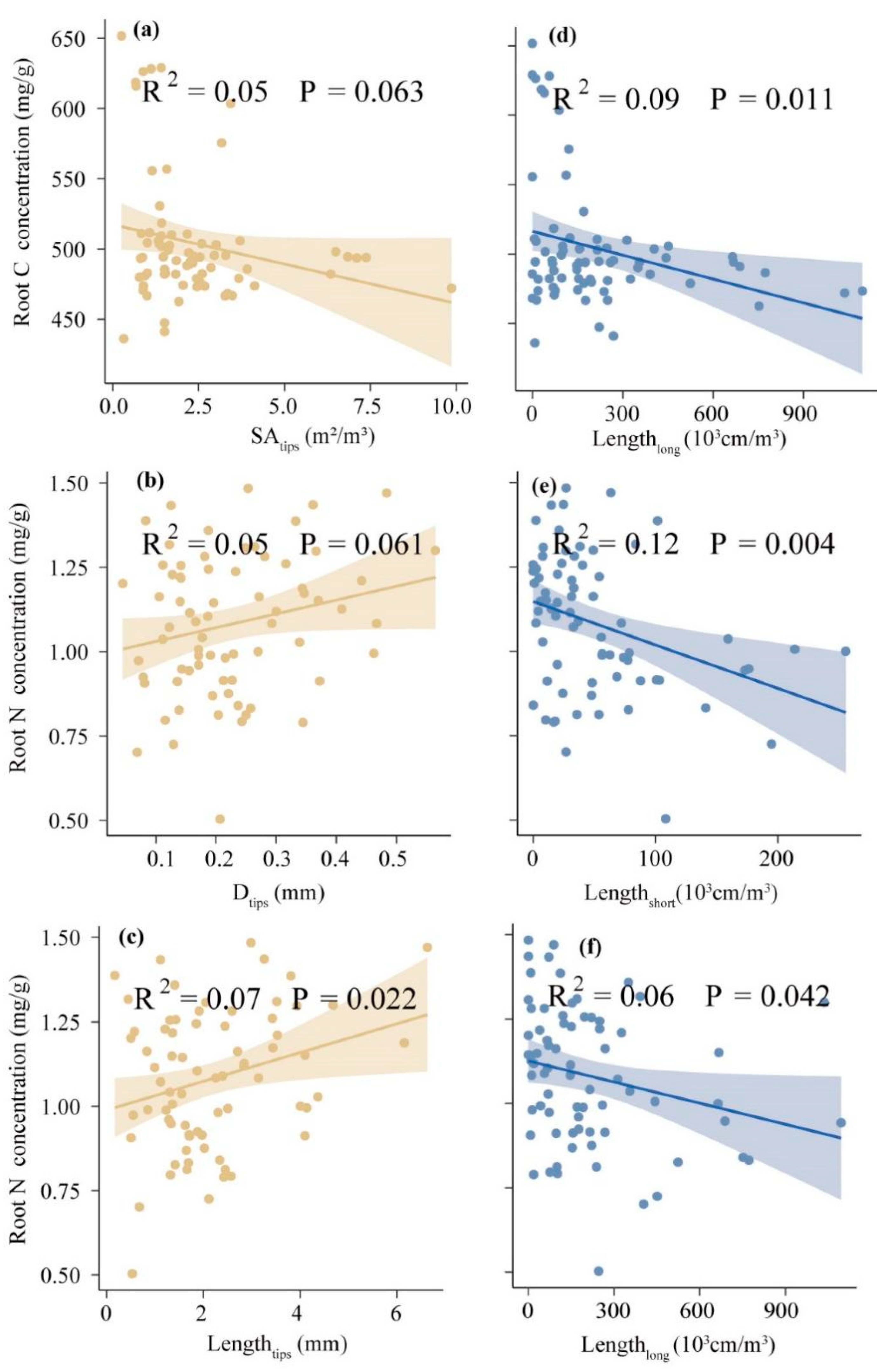

3.3. Relationships of ECM Morphological Traits with Plant Root C and N Nutrients

4. Discussion

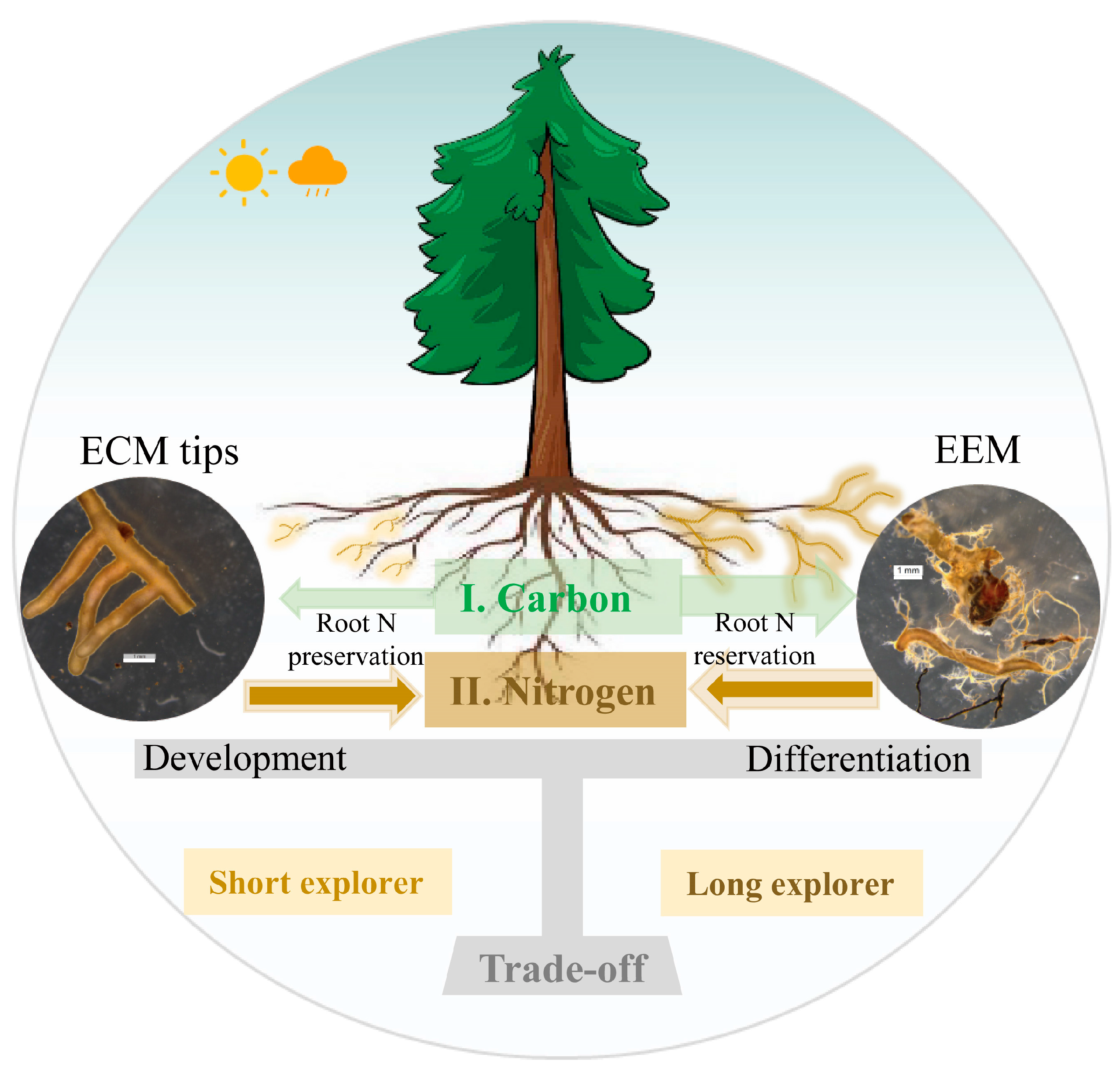

4.1. Ectomycorrhizal Nutrient-Foraging Behavior of Host Tree by Morphological Traits

4.2. ECM Morphological Traits Regulate Plant Nutrition Status in Different Ways

5. Limitation

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Yuke, Z. Characterizing the spatio-temporal dynamics and variability in climate extremes over the Tibetan Plateau during 1960–2012. J. Resour. Ecol. 2019, 10, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Q.; Yin, H. Plant nitrogen acquisition from inorganic and organic sources via root and mycelia pathways in ectomycorrhizal alpine forests. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 136, 107517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Shi, Z.; Liu, S.; Xu, G.; Cao, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; Feng, Q.; Centritto, M.; Cao, J. Leaf functional traits have more contributions than climate to the variations of leaf stable carbon isotope of different plant functional types on the eastern Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 871, 162036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Xu, G.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Cao, X.; Chen, M.; Chen, J.; Feng, Q.; Shi, Z. Contrasting responses of soil microbial biomass and extracellular enzyme activity along an elevation gradient on the eastern Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 974316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reithmeier, L.; Kernaghan, G. Availability of ectomycorrhizal fungi to black spruce above the present treeline in eastern Labrador. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e77527. [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie, J.E.; Hobbie, E.A. 15N in symbiotic fungi and plants estimates nitrogen and carbon flux rates in Arctic tundra. Ecology 2006, 87, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Heijden, M.G.; Bardgett, R.D.; Van Straalen, N.M. The unseen majority: Soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems. Ecol. Lett. 2008, 11, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Moreno, J.; Read, D. Mobilization and transfer of nutrients from litter to tree seedlings via the vegetative mycelium of ectomycorrhizal plants. New Phytol. 2000, 145, 301–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, E.A.; Agerer, R. Nitrogen isotopes in ectomycorrhizal sporocarps correspond to belowground exploration types. Plant Soil 2010, 327, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Pellitier, P.T.; Zak, D.R. Ectomycorrhizal fungal decay traits along a soil nitrogen gradient. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 2152–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, P.G.; Bruns, T.D. Priority effects determine the outcome of ectomycorrhizal competition between two Rhizopogon species colonizing Pinus muricata seedlings. New Phytol. 2005, 166, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogar, L.M.; Tavasieff, O.S.; Raab, T.K.; Peay, K.G. Does resource exchange in ectomycorrhizal symbiosis vary with competitive context and nitrogen addition? New Phytol. 2022, 233, 1331–1344. [Google Scholar]

- Lilleskov, E.; Hobbie, E.A.; Horton, T. Conservation of ectomycorrhizal fungi: Exploring the linkages between functional and taxonomic responses to anthropogenic N deposition. Fungal Ecol. 2011, 4, 174–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agerer, R. Exploration types of ectomycorrhizae: A proposal to classify ectomycorrhizal mycelial systems according to their patterns of differentiation and putative ecological importance. Mycorrhiza 2001, 11, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Genney, D.R.; Anderson, I.C.; Alexander, I.J. Fine-scale distribution of pine ectomycorrhizas and their extramatrical mycelium. New Phytol. 2006, 170, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bahr, A.; Ellström, M.; Bergh, J.; Wallander, H. Nitrogen leaching and ectomycorrhizal nitrogen retention capacity in a Norway spruce forest fertilized with nitrogen and phosphorus. Plant Soil 2015, 390, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörgensen, K.; Clemmensen, K.E.; Wallander, H.; Lindahl, B.D. Do ectomycorrhizal exploration types reflect mycelial foraging strategies? New Phytol. 2023, 237, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tedersoo, L.; Bahram, M.; Toots, M.; Diedhiou, A.G.; Henkel, T.W.; Kjøller, R.; Morris, M.H.; Nara, K.; Nouhra, E.; Peay, K.G. Towards global patterns in the diversity and community structure of ectomycorrhizal fungi. Mol. Ecol. 2012, 21, 4160–4170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rineau, F.; Stas, J.; Nguyen, N.H.; Kuyper, T.W.; Carleer, R.; Vangronsveld, J.; Colpaert, J.V.; Kennedy, P.G. Ectomycorrhizal fungal protein degradation ability predicted by soil organic nitrogen availability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 1391–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlay, R.D. Ecological aspects of mycorrhizal symbiosis: With special emphasis on the functional diversity of interactions involving the extraradical mycelium. J. Exp. Bot. 2008, 59, 1115–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemmensen, K.E.; Finlay, R.D.; Dahlberg, A.; Stenlid, J.; Wardle, D.A.; Lindahl, B.D. Carbon sequestration is related to mycorrhizal fungal community shifts during long-term succession in boreal forests. New Phytol. 2015, 205, 1525–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genre, A.; Lanfranco, L.; Perotto, S.; Bonfante, P. Unique and common traits in mycorrhizal symbioses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Linde, S.; Suz, L.M.; Orme, C.D.L.; Cox, F.; Andreae, H.; Asi, E.; Atkinson, B.; Benham, S.; Carroll, C.; Cools, N. Environment and host as large-scale controls of ectomycorrhizal fungi. Nature 2018, 558, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.W.; Nguyen, N.H.; Stefanski, A.; Han, Y.; Hobbie, S.E.; Montgomery, R.A.; Reich, P.B.; Kennedy, P.G. Ectomycorrhizal fungal response to warming is linked to poor host performance at the boreal-temperate ecotone. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017, 23, 1598–1609. [Google Scholar]

- Rambold, G.; Agerer, R. DEEMY–the concept of a characterization and determination system for ectomycorrhizae. Mycorrhiza 1997, 7, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; He, N.; Liu, C.; Xu, L.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, R.; Yu, G.; Sun, W.; Xiao, C. Variation and evolution of C: N ratio among different organs enable plants to adapt to N-limited environments. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 2534–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Razaq, M.; Salahuddin; Shen, H.-l.; Sher, H.; Zhang, P. Influence of biochar and nitrogen on fine root morphology, physiology, and chemistry of Acer mono. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.; Li, J.; Yang, K.; Tan, B.; Yin, R.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Cui, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, L. Variations and patterns of C and N stoichiometry in the first five root branch orders across 218 woody plant species. New Phytol. 2023, 238, 1838–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, R.P.; Brzostek, E.; Midgley, M.G. The mycorrhizal-associated nutrient economy: A new framework for predicting carbon–nutrient couplings in temperate forests. New Phytol. 2013, 199, 41–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, J.; Weigelt, A.; van Der Plas, F.; Laughlin, D.C.; Kuyper, T.W.; Guerrero-Ramirez, N.; Valverde-Barrantes, O.J.; Bruelheide, H.; Freschet, G.T.; Iversen, C.M. The fungal collaboration gradient dominates the root economics space in plants. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbie, E.A.; Bendiksen, K.; Thorp, N.R.; Ohenoja, E.; Ouimette, A.P. Climate records, isotopes, and C: N stoichiometry reveal carbon and nitrogen flux dynamics differ between functional groups of ectomycorrhizal fungi. Ecosystems 2022, 25, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedersoo, L.; Naadel, T.; Bahram, M.; Pritsch, K.; Buegger, F.; Leal, M.; Kõljalg, U.; Põldmaa, K. Enzymatic activities and stable isotope patterns of ectomycorrhizal fungi in relation to phylogeny and exploration types in an afrotropical rain forest. New Phytol. 2012, 195, 832–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, M.; Jiang, C.; Wang, X.; Feng, Q.; Liu, X.; Sun, O.J. Choices of ectomycorrhizal foraging strategy as an important mechanism of environmental adaptation in Faxon fir (Abies fargesii var. faxoniana). For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 495, 119372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Eamus, D.; Yu, Q.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, J. Climate constraints on growth and recruitment patterns of Abies faxoniana over altitudinal gradients in the Wanglang Natural Reserve, eastern Tibetan Plateau. Aust. J. Bot. 2012, 60, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, G.; Fu, B.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, K.; Pederson, N. The growth-ring variations of alpine shrub Rhododendron przewalskii reflect regional climate signals in the alpine environment of Miyaluo Town in Western Sichuan Province, China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2013, 33, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Keyimu, M.; Fan, Z.; Wang, X. Climate sensitivity of conifer growth doesn’t reveal distinct low–high dipole along the elevation gradient in the Wolong National Natural Reserve, SW China. Dendrochronologia 2020, 61, 125702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, K. Quantitative analysis by the point-centered quarter method. arXiv 2010, arXiv:1010.3303. [Google Scholar]

- Pregitzer, K.S.; DeForest, J.L.; Burton, A.J.; Allen, M.F.; Ruess, R.W.; Hendrick, R.L. Fine root architecture of nine North American trees. Ecol. Monogr. 2002, 72, 293–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.; Yang, N.; Pena, R.; Raghavan, V.; Polle, A.; Meier, I.C. Ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity increases phosphorus uptake efficiency of European beech. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 1200–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agerer, R. Fungal relationships and structural identity of their ectomycorrhizae. Mycol. Prog. 2006, 5, 67–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Jiang, C.; Wang, X.; Feng, Q.; Liu, X.; Tang, Z.; Sun, O.J. Nutrient trade-offs mediated by ectomycorrhizal strategies in plants: Evidence from an Abies species in subalpine forests. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 11, 5281–5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valladares, F.; Sanchez-Gomez, D.; Zavala, M.A. Quantitative estimation of phenotypic plasticity: Bridging the gap between the evolutionary concept and its ecological applications. J. Ecol. 2006, 94, 1103–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallaher, R.; Weldon, C.; Boswell, F. A semiautomated procedure for total nitrogen in plant and soil samples. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 1976, 40, 887–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.A.; Sommers, L.E. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. Methods Soil Anal. Part 2 Chem. Microbiol. Prop. 1983, 9, 539–579. [Google Scholar]

- Ladd, J.; Butler, J. Short-term assays of soil proteolytic enzyme activities using proteins and dipeptide derivatives as substrates. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1972, 4, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, D.; Kalra, Y.; Crumbaugh, J. Nitrate and exchangeable ammonium nitrogen. Soil Sampl. Methods Anal. 1993, 1, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

- New, M.; Hulme, M.; Jones, P. Representing twentieth-century space–time climate variability. Part II: Development of 1901–96 monthly grids of terrestrial surface climate. J. Clim. 2000, 13, 2217–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Gao, X.; Shen, Y.; Xu, C.; Shi, Y.; Giorgi, A. A daily temperature dataset over China and its application in validating a RCM simulation. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2009, 26, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Guo, W.; Fu, C. Calibrating and evaluating reanalysis surface temperature error by topographic correction. J. Clim. 2008, 21, 1440–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadud, M.A.; Nara, K.; Lian, C.; Ishida, T.A.; Hogetsu, T. Genet dynamics and ecological functions of the pioneer ectomycorrhizal fungi Laccaria amethystina and Laccaria laccata in a volcanic desert on Mount Fuji. Mycorrhiza 2014, 24, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosinger, C.; Sandén, H.; Matthews, B.; Mayer, M.; Godbold, D.L. Patterns in ectomycorrhizal diversity, community composition, and exploration types in European beech, pine, and spruce forests. Forests 2018, 9, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunrat, N.; Sansupa, C.; Sereenonchai, S.; Hatano, R. Short-term response of soil bacterial and fungal communities to fire in rotational shifting cultivation, northern Thailand. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2024, 196, 105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzyakov, Y.; Razavi, B.S. Rhizosphere size and shape: Temporal dynamics and spatial stationarity. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2019, 135, 343–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- See, C.R.; Keller, A.B.; Hobbie, S.E.; Kennedy, P.G.; Weber, P.K.; Pett-Ridge, J. Hyphae move matter and microbes to mineral microsites: Integrating the hyphosphere into conceptual models of soil organic matter stabilization. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 2527–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, C.W. The advancing mycelial frontier of ectomycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 2021, 230, 1296–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekblad, A.; Wallander, H.; Godbold, D.L.; Cruz, C.; Johnson, D.; Baldrian, P.; Björk, R.; Epron, D.; Kieliszewska-Rokicka, B.; Kjøller, R. The production and turnover of extramatrical mycelium of ectomycorrhizal fungi in forest soils: Role in carbon cycling. Plant Soil 2013, 366, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, C.W.; Mielke, L.; Stefanski, A.; Bermudez, R.; Hobbie, S.E.; Montgomery, R.A.; Reich, P.B.; Kennedy, P.G. Climate change–induced stress disrupts ectomycorrhizal interaction networks at the boreal–temperate ecotone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2221619120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Yin, H.; Kong, D.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Q.; Guo, W.; Valverde-Barrantes, O.J.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z. Precipitation, rather than temperature drives coordination of multidimensional root traits with ectomycorrhizal fungi in alpine coniferous forests. J. Ecol. 2023, 111, 1935–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, F. Ektomykorrhizen an Fagus sylvatica. In Charakter Isierung Und Identifizierung, ökologische Kennzeichnung Undunsterile Kultivierung; Libri Botanici; IHV-Verlag: Eching, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Defrenne, C.E.; Philpott, T.J.; Guichon, S.H.; Roach, W.J.; Pickles, B.J.; Simard, S.W. Shifts in ectomycorrhizal fungal communities and exploration types relate to the environment and fine-root traits across interior Douglas-fir forests of western Canada. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argüelles-Moyao, A.; Garibay-Orijel, R. Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities in high mountain conifer forests in central Mexico and their potential use in the assisted migration of Abies religiosa. Mycorrhiza 2018, 28, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedersoo, L.; Smith, M.E. Lineages of ectomycorrhizal fungi revisited: Foraging strategies and novel lineages revealed by sequences from belowground. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2013, 27, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, H.; Zhang, P.; Wang, Q.; Wang, D.; Feng, Q.; Yin, H. Shifts in ectomycorrhizal exploration types complement root traits in nutrient foraging of alpine coniferous forests along an elevation gradient. Plant Soil 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.C.; Street, N.R.; Sjödin, A.; Lee, N.M.; Högberg, M.N.; Näsholm, T.; Hurry, V. Microbial community response to growing season and plant nutrient optimisation in a boreal Norway spruce forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 125, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khokon, A.M.; Janz, D.; Polle, A. Ectomycorrhizal diversity, taxon-specific traits and root N uptake in temperate beech forests. New Phytol. 2023, 239, 739–751. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, C.W.; Langley, J.A.; Chapman, S.; McCormack, M.L.; Koide, R.T. The decomposition of ectomycorrhizal fungal necromass. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 93, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rineau, F.; Garbaye, J. Does forest liming impact the enzymatic profiles of ectomycorrhizal communities through specialized fungal symbionts? Mycorrhiza 2009, 19, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.M.; Berkelmans, R.; van Oppen, M.J.; Mieog, J.C.; Sinclair, W. A community change in the algal endosymbionts of a scleractinian coral following a natural bleaching event: Field evidence of acclimatization. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 275, 1359–1365. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-García, L.B.; De Deyn, G.B.; Pugnaire, F.I.; Kothamasi, D.; van der Heijden, M.G. Symbiotic soil fungi enhance ecosystem resilience to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 5228–5236. [Google Scholar]

- Högberg, M.N.; Högberg, P.; Wallander, H.; Nilsson, L.O. Carbon–nitrogen relations of ectomycorrhizal mycelium across a natural nitrogen supply gradient in boreal forest. New Phytol. 2021, 232, 1839–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, L.; Rosenstock, N.; Van Der Linde, S.; Braun, S. Nitrogen deposition changes ectomycorrhizal communities in Swiss beech forests. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 605, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guignabert, A.; Delerue, F.; Gonzalez, M.; Augusto, L.; Bakker, M.R. Effects of management practices and topography on ectomycorrhizal fungi of maritime pine during seedling recruitment. Forests 2018, 9, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Ma, C.; Zhang, Q.; Li, L.; Chen, X.; Zeng, H.; Guo, D. Leading dimensions in absorptive root trait variation across 96 subtropical forest species. New Phytol. 2014, 203, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierick, K.; Link, R.M.; Leuschner, C.; Homeier, J. Elevational trends of tree fine root traits in species-rich tropical Andean forests. Oikos 2023, 2023, e08975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumet, C.; Birouste, M.; Picon-Cochard, C.; Ghestem, M.; Osman, N.; Vrignon-Brenas, S.; Cao, K.F.; Stokes, A. Root structure–function relationships in 74 species: Evidence of a root economics spectrum related to carbon economy. New Phytol. 2016, 210, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weemstra, M.; Mommer, L.; Visser, E.J.; van Ruijven, J.; Kuyper, T.W.; Mohren, G.M.; Sterck, F.J. Towards a multidimensional root trait framework: A tree root review. New Phytol. 2016, 211, 1159–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselquist, N.J.; Metcalfe, D.B.; Inselsbacher, E.; Stangl, Z.; Oren, R.; Näsholm, T.; Högberg, P. Greater carbon allocation to mycorrhizal fungi reduces tree nitrogen uptake in a boreal forest. Ecology 2016, 97, 1012–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigt, R.B.; Raidl, S.; Verma, R.; Agerer, R. Exploration type-specific standard values of extramatrical mycelium–a step towards quantifying ectomycorrhizal space occupation and biomass in natural soil. Mycol. Prog. 2012, 11, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näsholm, T.; Högberg, P.; Franklin, O.; Metcalfe, D.; Keel, S.G.; Campbell, C.; Hurry, V.; Linder, S.; Högberg, M.N. Are ectomycorrhizal fungi alleviating or aggravating nitrogen limitation of tree growth in boreal forests? New Phytol. 2013, 198, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, I.C.; Genney, D.R.; Alexander, I.J. Fine-scale diversity and distribution of ectomycorrhizal fungal mycelium in a S cots pine forest. New Phytol. 2014, 201, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sites | Statistical Parameter | Root C (mg/g) | Root N (mg/g) | Root C:N | Lengthshort (103 cm/m3) | Lengthlong (103 cm/m3) | Dtips (mm) | Lengthtips (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wolong Natural Reserve | N | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 | 40 |

| Mean | 485.9 | 10.4 | 48.90 | 73.40 | 300.06 | 0.21 | 1.74 | |

| SD | 17.0 | 2.1 | 12.43 | 61.20 | 267.87 | 0.12 | 1.13 | |

| CV | 3.5% | 19.9% | 25.4% | 83.4% | 89.3% | 58.1% | 65.0% | |

| Miyaluo Natural Reserve | N | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Mean | 484.4 | 10.0 | 49.78 | 22.67 | 149.12 | 0.24 | 2.64 | |

| SD | 16.6 | 1.6 | 8.08 | 23.40 | 175.88 | 0.09 | 1.28 | |

| CV | 3.4% | 15.9% | 16.2% | 103.2% | 117.9% | 38.3% | 48.6% | |

| Wanglang Natural Reserve | N | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Mean | 569.2 | 12.6 | 45.22 | 24.62 | 70.66 | 0.26 | 2.81 | |

| SD | 56.2 | 1.2 | 4.83 | 26.74 | 54.86 | 0.10 | 1.38 | |

| CV | 9.9% | 9.9% | 10.7% | 108.6% | 77.6% | 40.6% | 49.2% | |

| RDPI | 0.86 | 0.89 | 0.35 | 0.52 | ||||

| Significance among sites | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p > 0.05 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p > 0.05 | p < 0.005 | |

| Factors | SoilCN | Soil Available N | Soil Protease | MAT | MAP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | p | Estimate | p | Estimate | p | Estimate | p | Estimate | p | |

| Lengthtips | 0.03 | >0.05 | 0.002 | >0.05 | 0.09 | <0.05 | −0.05 | >0.05 | −0.01 | >0.05 |

| Dtips | 0.002 | >0.05 | −0.0003 | >0.05 | 0.005 | >0.05 | −0.006 | >0.05 | −0.0004 | >0.05 |

| SAtips | 0.04 | >0.05 | 0.005 | >0.05 | −0.01 | >0.05 | −0.02 | >0.05 | 0.02 | <0.05 |

| Ccontact | 0.0002 | >0.05 | 0.0008 | >0.05 | −0.02 | <0.001 | −0.04 | <0.01 | 0.000 | >0.05 |

| Cshort | −0.0003 | >0.05 | 0.0004 | >0.05 | 0.02 | <0.001 | 0.01 | >0.05 | −0.0004 | >0.05 |

| Clong | −0.0008 | >0.05 | −0.001 | >0.05 | −0.004 | >0.05 | 0.03 | <0.05 | 0.0009 | >0.05 |

| Lengthshort | 0.04 | >0.05 | −0.007 | >0.05 | 1.75 | >0.05 | 14.18 | <0.01 | 1.12 | <0.001 |

| Lengthlong | −5.04 | >0.05 | −0.12 | >0.05 | −9.5 | >0.05 | 25.14 | >0.05 | 2.42 | <0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Li, X.; Tang, Z.; Xu, G. Morphological Plasticity of Ectomycorrhizal Symbiosis Promotes Adaptation of Faxon Fir (Abies fargesii var. faxoniana) to Altitudinal and Environmental Changes on Eastern Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Forests 2025, 16, 1670. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111670

Chen L, Li X, Tang Z, Xu G. Morphological Plasticity of Ectomycorrhizal Symbiosis Promotes Adaptation of Faxon Fir (Abies fargesii var. faxoniana) to Altitudinal and Environmental Changes on Eastern Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Forests. 2025; 16(11):1670. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111670

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Lulu, Xuhua Li, Zuoxin Tang, and Gexi Xu. 2025. "Morphological Plasticity of Ectomycorrhizal Symbiosis Promotes Adaptation of Faxon Fir (Abies fargesii var. faxoniana) to Altitudinal and Environmental Changes on Eastern Qinghai–Tibet Plateau" Forests 16, no. 11: 1670. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111670

APA StyleChen, L., Li, X., Tang, Z., & Xu, G. (2025). Morphological Plasticity of Ectomycorrhizal Symbiosis Promotes Adaptation of Faxon Fir (Abies fargesii var. faxoniana) to Altitudinal and Environmental Changes on Eastern Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Forests, 16(11), 1670. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16111670