Abstract

The main objective of the study was to evaluate the colour changes generated by outdoor exposure on spruce (Picea abies L. Karst) samples used as shingles for the roof of a traditional Maramures gate. Additionally, samples made of oak (Quercus petraea Liebl.) have been used to simulate the gate pillar. The specimens have been treated with boiled linseed oil and exposed to the outdoor environment for nine months under two different trial positions. The colour and moisture content changes in the samples have been periodically evaluated. Reactions of the samples from two species have been analysed considering three different variables, such as exposure time, treatment chemical, and positioning during their outdoor exposure. The samples vertically positioned showed fewer discolouration compared to those with inclined exposure. The total variation in colour increased as the length of exposure time increased. After nine months, the highest variation, based on the ΔE* values, was recorded in the category of untreated samples exposed at an angle of 60° to the horizontal, which showed values of ΔE* = 24.87 for oak and ΔE* = 31.16 for spruce, respectively. The oil treatment had a significant impact only on spruce samples having orthogonal exposure. The findings of this study have the potential to provide a better understanding of such species used for construction applications in relation to weathering.

1. Introduction

Similarly to other biological materials, wood is also susceptible to biodegradation, due to biotic (bacteria, fungi, insects) and abiotic agents (atmospheric events). Any wood member exposed to the direct action of the weathering due to moisture and solar radiation is subject to a form of degradation of the surface, which alters its appearance by discolouration [1,2]. When wood products are placed outdoors in contact with atmospheric agents, the surface originally finished becomes rough due to the swelling of the fibres, fissures appear that become enlarged with time, and the grain tends to loosen. The boards bend and distort and tend to break the joints during fastening with screws and nails. The rough surface changes colour and becomes a non-aesthetic receptacle for dirt and mould. The wood loses its surface cohesion, becomes crumbly, and small pieces could crumble [3,4]. All these effects, caused by a combination of light, moisture, mechanical forces and heat, are described by weathering. Among these agents, UV radiation is mainly responsible for the chemical processes that induce discolouration of wood surfaces [5,6]. Photochemical degradation of wood due to sunlight occurs fairly quickly on the exposed surface. The initial change in colour of the wood towards yellow or dark brown usually precedes the final grey colour [3,7]. These colour changes are linked to the decomposition of lignin in the surface wood cells and are a simple superficial concept [8,9]. They occur only up to a depth between 0.05 and 0.5 mm and are the result of the ultraviolet part of the sunlight that triggers photodegradation.

The two most important factors of weathering, sunlight and humidity, tend to operate at different times. Exposed wood can be irradiated after being wet by rain, or when the moisture content of the surface has increased overnight due to mist [4,5]. When wood is used in outdoor conditions, some major rules should be taken into consideration to reduce the process of degradation.

First, it is recommended to use wood species with a greater natural durability. Secondly, an adequate construction solution is required. Third, a surface treatment can be used to extend the service life of the material [10].

Other parameters that affect the surface degradation of the wood are time, location and exposure route [11]. A study conducted by Schnabel et al. investigated a model of discolouration for white fir (Abies alba Mill.) and larch (Larix decidua Mill.) during natural weathering [12]. Rüther and Jelle tested the influence of the exposure route on the colour change, looking for a correlation between solar radiation, wind direction during the rains and colour change in treated and natural wood [6]. Test results for different exposures showed a greater change in colour (ΔE*) on samples exposed to the south at an angle of 30° to the horizontal, while all other samples were exposed at an angle of 90°. Other samples exposed to the east, south, west and north showed a smaller variation than the previous ones. The rain leaches out natural and photodegraded extractives over time, and the colour of outdoor wooden constructions becomes less natural, turning towards grey, as previously mentioned [2].

The focus of this study is on traditional wooden constructions in the north of Romania. Very unique for the construction method, dimensions and the elaborate decorations that adorn the entire structure, the Maramures gates hold in the ancient culture of the region a much deeper meaning than just an ornamental one, as illustrated in Figure 1. The design of traditional Maramures gates can show a few variations, linked to the number, size and characteristics of the elements that compose them. The construction system is generally characterised by three fundamental elements [13]:

- The foundation, nowadays made of reinforced concrete, supports the entire structure.

- The frame, generally made of oak wood, is composed of two or more support columns, topped by wooden beams and buttresses. Doors of different sizes can be arranged between the columns. Hand-carved when the wood is still fresh—and therefore easier to work—oak guarantees a long life and a pleasant aesthetic appearance to the structure. Oak wood shows significant swelling due to changes in environmental humidity, and the presence of numerous parenchymatous rays requires a very slow drying session. In case of forced drying, honeycomb-shaped cracks may form on the surface [13], compromising the beauty of the decoration and the performance of the material.

- The protective roof is made up of wooden trusses and covered with spruce or fir wooden shingles. The main function of the roof is the partial protection of the underlying structures, slowing down the degradation process due to rain, snow, hail, wind and solar radiation. In the design of wooden sheds, the material used as well as the shape and profile of the elements assume particular importance to prevent the infiltration and stagnation of water [14]. Shingles, used for centuries as a roofing material, give originality and a pleasant aesthetic appearance to the structures [15]. Made with natural and biodegradable materials such as wood, in Romania, they are still the result of the skill of local carpenters and artisans. Manually, by sawing or splitting the trunk in a radial direction, the shingles are interchangeable elements that can assume different shapes and sizes depending on the construction needs [15]. For the construction of a roof, the shingles overlap in a minimum of two and a maximum of four layers, depending on the inclination and slope of the roof pitches [14].

Figure 1.

Example of an eight-column Maramures gate [13].

Part of the Maramures region’s artistic and cultural heritage, the gates are still the result of artisanal skills that are disappearing nowadays, replaced by modern industrial processes dictated by automation. More initiatives should be allocated for their protection and safeguarding to shed light on and keep their ancestral ethnographic value.

A fact-finding investigation carried out in the Maramures region revealed a century-old treatment, such as the use of linseed oil applied on the wood surfaces to form a protective and waterproof layer. But the locals still sometimes skip the oil application to these constructions. There is little information on the weathering process and its effects on traditional wooden gates in Romania. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to evaluate the discolourations generated by weathering on wood samples made of spruce, used as shingles for the roof of a traditional Maramures gate. Samples made of oak have also been used to simulate the gate pillar. Discolourations have been analysed as a function of three different variables: exposure time, applied treatment and position assigned to the samples during their outdoor exposure.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Samples made of spruce (Picea abies L. Karst) were used for the experiments. Spruce is a whitish wood with evident annual rings. There is a gradual transition from the early to the late wood, which is always subtle. It has small resin pockets and presents a fine texture and straight grain. Spruce wood is light (dry density of 410 kg/m3) and soft (Brinell hardness of 12 N/mm2). Drying is quick and easy. The surface treatment is not problematic, although the resin pockets must be treated beforehand.

Additionally, samples made of oak (Quercus petraea Liebl.) were used. Sesile oak presents a yellowish-white sapwood and brown heartwood, moving to darker tones over time. Grain is straight with a coarse, uneven texture. It may have irregular or interlocked grain. It is a ring-porous species; 2–4 rows of large, exclusively solitary earlywood pores, numerous small to very small latewood pores in radial arrangement; tyloses are abundant; growth rings distinct; rays are large and visible without a lens; apotracheal parenchyma diffuse-in-aggregates. Its density is about 720–750 kg/m3. The oak wood is rated as having very good resistance to decay. It produces good results with hand and machine tools but can react with iron (particularly when wet) and cause staining and discolouration.

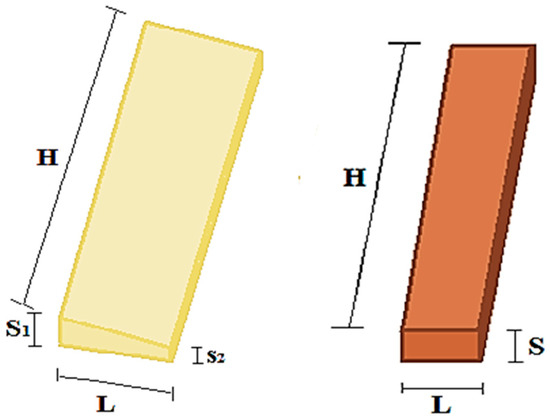

Figure 2 and Table 1 display the shape, dimensions and the number of the samples. The spruce samples were made by splitting the log in a radial direction to obtain the shingles’ shape, while the oak samples were obtained by tangential sawing to simulate the gate’s vertical elements. In this study, spruce samples were best represented compared to oak samples.

Figure 2.

Shape and dimensions of the samples: spruce (left) and oak (right).

Table 1.

Samples used for the experiments.

The initial moisture content of the samples was about 9 ± 1% for oak and 10 ± 2% for spruce. Before any test was carried out, the wood material was kept under controlled conditions at a temperature of 20 °C and the air relative humidity of 65 ± 5% for 24 h. Experiments proved that a one-day conditioning right before the colour measurement can generate roughly equal moisture content on the sample surfaces [2].

A natural siccative, boiled linseed oil, was used to treat half of the samples. Two coats of oil (25 g/m2 each layer), with a 24 h drying phase in between, were applied to the wooden surfaces of half of the samples by using a soft brush (Figure 3). The oil was allowed to soak for about 15–20 min after each application, and then all excess was wiped away to prevent a sticky finish [16]. No treatment was applied to the other half of the samples.

Figure 3.

Application of linseed oil by brush.

2.2. Outdoor Exposure of the Samples

To expose the samples to weathering, a trial stand with a south-east orientation and located on a building terrace in Brașov was used. Geographical data for Brașov are: 45.65 latitude, 25.61 longitude, at an altitude of 625 m. The average annual temperature in Brașov is 7.6 °C, while the absolute maximum temperature is 37 °C in August. The humidity of the air is, on average, about 75%. The atmospheric precipitation is around 600–700 mm/year. Wind flows from the ground with a predominant direction to the west and north-west and with average speeds between 1.5 and 3.2 m/s. The average daily solar radiation in the Brașov area is approximately 4.84 kWh/m2/day. Brașov was selected as the sole site for practical monitoring reasons, while its continental-mountainous climate is broadly comparable to the Maramures region, making the results relevant to the target region.

The test period was set for nine months, between April and January of the following year, to capture the main seasonal variations that drive wood weathering, as the first year is known to produce the most rapid and visible changes. During the exposure period, the temperatures were low in the winter and high in the summer. The relative air humidity was high in the winter and lowest in April. Precipitations have a peak in summer, but it was very dry in December.

To fix the samples on the stand at inclinations of 60° and 90° to the horizontal line, metal supports were used, as depicted in Figure 4. The inclinations assigned to the samples simulated the position of the different elements of the traditional gates. The inclined elements made of spruce reproduce the shingles on the roofs. In contrast, the orthogonal elements made of oak simulate the vertical support structures in the form of columns and beams with decorations. However, the two positions have been set for both types of samples. Although replication of oak samples was limited, this supplementary trial provided indicative data on how orientation and material choice affect weathering in heritage-relevant structures.

Figure 4.

Trial stand with samples exposed at 90° (front view of the stand) and 60° (right side of the stand).

Treated and untreated samples were exposed to weathering for one, two, three and nine months. The control samples treated with linseed oil and untreated were placed in the dark inside a special cabinet for subsequent visual evaluation. After each outdoor exposure, one sample was retained as reference material from each category to enable subsequent comparisons.

2.3. Colour Measurement of the Samples

The changes in colour of the samples were measured before and after each exposure period. A spectral photometer model CR-400 (Konica Minolta, Tokyo, Japan) device was used for the colour measurement (Figure 5) according to the ISO standard [17]. To achieve accurate measurements, the white calibration was performed using the white calibration plate. Colour variations were evaluated using the CIE L*a*b* system, where: L* represents colour brightness ranging from 0 (black) to 100 (white), a* is the red-green colour coordinate ranging between −127 (pure green) and +127 (pure red) and b* is the yellow-blue colour coordinate going from −127 (pure blue) to +127 (pure yellow). The total colour change ΔE* was calculated and used for comparison of colour changes between different samples [17]. Five measurements per sample for spruce and four measurements per sample for oak were taken in the same spots (seen in Figure 5), and the average values were used for the colour change evaluations for different exposure spans. To avoid data alteration, the areas showing defects were excluded from any measurements.

Figure 5.

CR-400 Konica Minolta device.

2.4. Determination of the Moisture Content of the Samples

The changes in moisture content of the samples were measured before and after each exposure period. The initial (control), intermediate (1st, 2nd, 3rd month) and final (9th month) moisture content of the samples were determined with a non-destructive method by using a contact hygrometer of Merlin Hm8-Ws25 type (Figure 6). All data in this study were processed using the SPSS software version 23 [18]. ANOVA analysis of the colour coordinates for spruce and oak samples as a function of three factors (time, treatment, inclination) was performed.

Figure 6.

Contact hygrometer of Merlin type.

3. Results

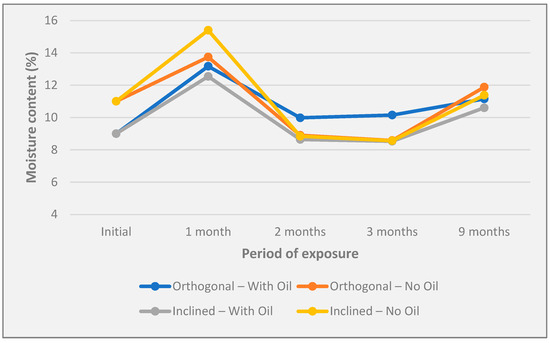

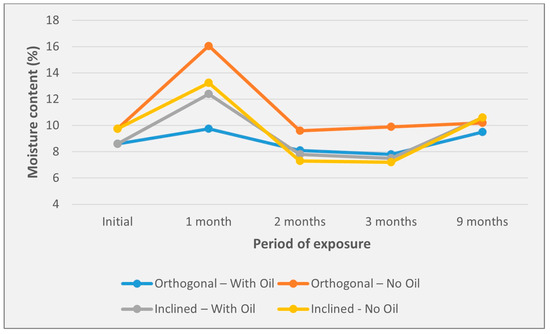

3.1. Evaluation of the Moisture Content of the Samples

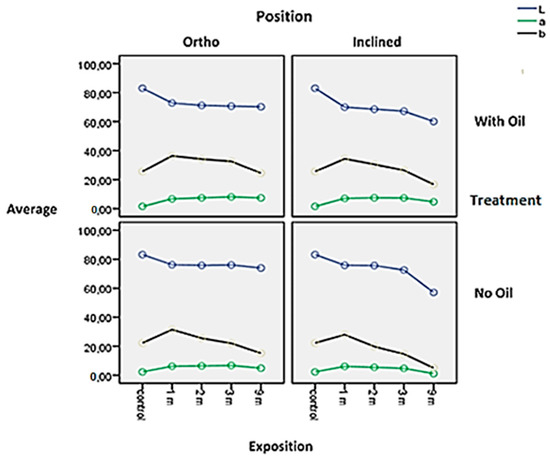

Table 2, along with Figure 7 and Figure 8, displays the moisture content of the samples under study. The trend of moisture content in the two species was found to be similar. Under the influence of abundant rainfall, which reaches maximum values between April and May, the percentage moisture content shows a sudden increase in the first month of exposure in all categories of the sample. It decreases and stabilises its values in the summer, rises again after nine months of exposure, and all samples seem to balance towards the values ranging between 10 and 12%. In both species, the category of samples exposed in the orthogonal direction and were oil-treated appeared to be more stable to moisture content variation.

Table 2.

Moisture content of the samples as a function of species, treatment and exposure position.

Figure 7.

Moisture content of spruce as a function of treatment, time and exposure position.

Figure 8.

Moisture content of oak as a function of treatment, time and exposure position.

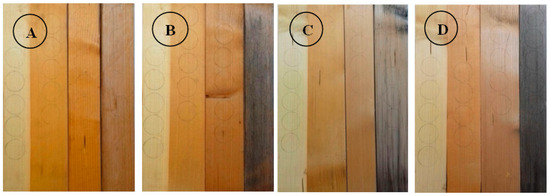

3.2. Visual Analysis of the Wood Surfaces of the Samples

The colour and its stability influence the aesthetic and visual appearance of wooden artefacts. When the wood is exposed to atmospheric agents, its colour becomes particularly sensitive to the action of UV radiation and humidity [2].

Several other factors affect the degree of discolouration, including the wood species, treatment and exposure time. The evolution of colour, induced by the atmospheric erosion processes, is presented in this study through a visual-sensorial analysis. It is a subjective analysis; therefore, it varies depending on the observer (Figure 9 and Figure 10). This analysis can still be considered reliable if associated with objective colourimetric data detected with the aid of specific devices. The visual analysis of spruce samples highlights a noticeable greying process that is particularly accentuated on samples arranged with an inclination of 60° to the horizontal, after nine months of exposure. The greatest chromatic stability was noticed on samples exposed in the orthogonal direction and treated with cooked linseed oil (Figure 9). A tendency to grey is observed on oak samples exposed at an inclination of 60° to the horizontal, more marked in the absence of treatment. More stable, the samples exposed in the orthogonal direction show a lighter colour after nine months of exposure (Figure 10).

Figure 9.

Stages of discolouration on spruce wood shingles (order of samples: control, 1, 3 and 9 months of exposure): (A) orthogonal samples—with oil; (B) inclined samples—with oil; (C) orthogonal samples—no oil; and (D) inclined samples—no oil.

Figure 10.

Stages of discolouration on oak wood strips (order of samples: control, 1, 3 and 9 months of exposure): (A) orthogonal samples—with oil; (B) inclined samples—with oil; (C) orthogonal samples—no oil; and (D) inclined samples—no oil.

3.3. Evaluation of Colour Changes in the Samples

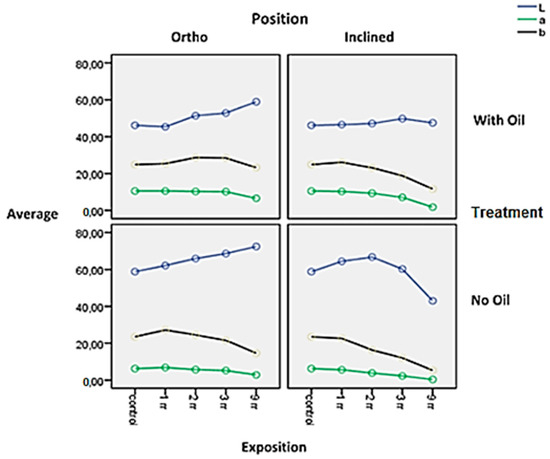

The variations in the three parameters L* (brightness), a* (red-green) and b* (yellow-blue) under the influence of atmospheric agents for the different classes of samples are displayed in Table 3 and Figure 11 and Figure 12. Figure 11 shows the trends of colour coordinates L*, a* and b* for spruce, as a function of exposure time, treatment and position (60° or 90°).

Table 3.

CIELab parameter values as a function of exposure time, treatment and position.

Figure 11.

Colour changes on spruce shingles as a function of exposure time, treatment (with or without oil) and position (orthogonal or inclined).

Figure 12.

Colour changes on oak samples as a function of exposure time, treatment (with or without oil) and position (orthogonal or inclined).

The brightness L* of the spruce samples decreases in the first month of exposure, tends to stabilise for the following three months for all types of samples and then continues to decrease only for samples exposed at an angle of 60°, both treated and untreated. In line with the visual examination, inclined samples tend to be more grey than orthogonal samples, and the treatment did not influence the samples’ brightness in the case of spruce. The a* coordinate shows an initial slow increase which leads to a slight reddening of the surfaces, stabilises its values and then decreases slightly in all the categories of the samples. The b* coordinate exhibits a similar trend to the previous one. Still, unlike a*, there are greater variations in the first month of exposure, which translates into a colour change towards a higher concentration of yellow. Subsequently, it starts to decrease towards yellow-blue tones constantly.

Figure 12 shows the trends of colour coordinates L*, a* and b* for oak, as a function of exposure time, treatment and position (60° or 90°). In oak, the increase in brightness L* on samples exposed in the orthogonal direction reveals a lightening of the wood surfaces. The samples exposed to an inclination of 60° show a trend of L* initially increasing, then decreasing, which becomes particularly pronounced in the category of untreated samples, with the initial value of 59.09 dropping to 43.29 at the end of the nine months of exposure. The inclined surfaces have shown an important change towards shades of grey, while the vertical samples have faded based on visual observation. The a* coordinate tends to remain stable in the first months, then slowly moves towards red-green shades. The b* coordinate, after a slight initial yellowing, turns towards yellow-blue tones. In the second case, the treatment seems to contribute to a lightening of the surfaces, which possibly is due to the leaching of some coloured extractives [2,19,20].

The results of this study showed an increased value of the coordinates a* and b*, noticed in almost all the categories of samples during the initial period of exposure, with a consequent increase in colour saturation. A maximum value was reached after 30 days of exposure, followed by a reduction in the parameters mentioned above and a final tendency of the surfaces towards grey, more conspicuous in spruce. Such a result was also attested by Schnabel et al. [12]. On the other hand, on oak samples, a discordant behaviour emerged between the different categories. The inclined surfaces showed a significant evolution of the colour towards shades of grey, while, on the contrary, the samples exposed in the vertical direction faded.

The spruce samples exposed at an angle of 60° showed a greater variation than the orthogonal ones towards grey. This demonstrates that the inclination influenced the changes in parameter L*. On oak samples, the application of the siccative oil did not slow down the lightening process of the surfaces. Ozgenc et al. [9] proved that linseed oil tends to lighten the exposed surfaces. On the other hand, it seemed to prevent the change towards negative values in the category of samples with inclined exposure at an angle of 60°, limiting the darkening of the surfaces.

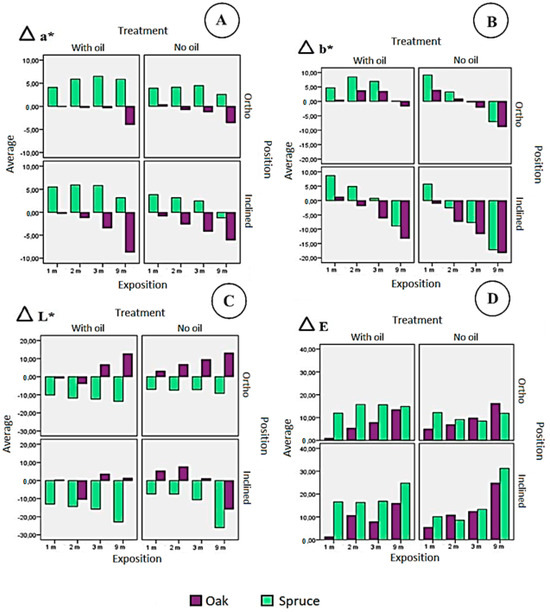

Figure 13 presents the partial colour variations Δa*, Δb*, ΔL* and the total colour variation ΔE* for both species, as a function of exposure, position and treatment.

Figure 13.

Partial colour variations Δa* (A), Δb* (B), ΔL* (C) and the total colour variation ΔE* (D) as a function of exposure time, treatment (with or no oil) and position (orthogonal or inclined) for the two species.

Positive values of Δa* and Δb* indicate an increase in the yellow colour and the tendency of the surface towards a pinkish colour. Negative values indicate an increase in the blue colour and an aptitude to perceive the surface as green [6]. The Δa* coordinate shows different values in the two species: initially increasing, then decreasing for spruce; decreasing in oak and moving towards negative values, which highlights a change in colour towards shades of green. For spruce, the highest values of Δa* are found in the third month of exposure in the category of orthogonal samples treated with oil (Δa* = 6.5). For oak, the highest values of Δa* are found in the first month of exposure on untreated orthogonal samples (Δa* = 0.4). The lowest values occur, for both species, in the ninth month of exposure, in the category of inclined samples, untreated for spruce (Δa* = −1.18) and inclined, treated with linseed oil for oak (Δa* = −8.73). A similar trend for the two species is noticed for Δb* values, initially rising, then decreasing as the exposure time increases. The highest values are found between the first and second month of exposure in the category of untreated orthogonal samples, having Δb* = 9.18 for spruce and Δb* = 3.87 for oak. The lowest values occur for both species after nine months of exposure in the category of untreated inclined samples, with Δb* = −18.21 for spruce and Δb* = −17.18 for oak.

Figure 13A,B shows the tendency of the colour to move in the direction of red and yellow tones during the first months of exposure. Then it turns progressively towards shades of blue and green due to the combined action of UV rays and humidity.

One of the most relevant parameters, as an indicator of the quality of the wood surface, is the minimum brightness value ΔL* [9]. Negative ΔL* values occur when surfaces tend to darken due to atmospheric erosion processes [6]. The highest values are found for both species on untreated orthogonal samples, with ΔL* = 9.21 for spruce and ΔL* = 13.15 for oak. The lowest values occur in the category of untreated inclined samples, where ΔL* = −26.09 for spruce and ΔL* = −15.81 for oak. It appears that on spruce samples, the application of the siccative oil did not guarantee any significant improvement of the sample’s colour (Figure 13C). Furthermore, in oak, the treatment seems to have prevented the category of samples exposed to an inclination of 60° from taking negative values.

The tendency of the different sample categories to lose colour was observed through the total colour change (ΔE*). Generally, the total variation in colour increased as the length of exposure time to natural atmospheric agents increased. After nine months, the highest variation, based on the ΔE* values, was recorded in the category of untreated samples exposed at an angle of 60° to the horizontal, which showed values of ΔE* = 24.87 for oak and ΔE* = 31.16 for spruce, respectively. Such high values of the total colour changes indicate a totally different colour for both species as displayed in Figure 9 and Figure 10. The lowest variation was found in the category of samples exposed in the orthogonal direction, for both treated and untreated samples. Furthermore, oak samples showed less colour stability than that of spruce samples.

The overall colour loss ΔE* was found to be directly proportional to the exposure time. The analysis of ΔE* revealed a good performance of the treatment on the orthogonal spruce samples, which show a fair colour stability over the nine months of exposure. Based on ΔE* values, the highest colour variation was recorded in the category of untreated samples having inclined exposure. Overall, the positioning of the samples appears to be more influential on colour stability as compared to the influence of treatment. The reason for these results can be explained as a combination of different factors: greater incidence of solar radiation, water and snow on surfaces, associated with higher erosion and evaporation processes caused by the wind [2,21]. All these factors are intrinsically linked and influence in synergy the evolution of colour and the progress of the erosive processes more generally [19,21].

Another variable must be included in the complex system of interactions between climatic factors, such as the orientation to the cardinal points (north, south, west, east) and the different importance they assume in various locations on Earth. Fundamental elements such as wind direction and intensity, incidence of light, direction and intensity of rainfall depend on the orientation [2,12]. Leaving aside the direction of the wind, which in the city of Brașov blows predominantly in the north-west direction, solar radiation and humidity can be assumed as the prevailing factors in this study. The trend in the moisture content of the samples partially confirms the hypothesis. Greater fluctuations in humidity, enhanced by the alternation of evaporation and leaching processes caused by the action of light and rain, may be related to a greater instability of the colour shown by the class of untreated samples with inclined exposure. On the contrary, a more stable trend in the moisture content in the category exposed in the orthogonal direction and treated with the siccative oil may favour the slight colour changes shown by spruce during the nine months of exposure. Finally, it can be hypothesised that, based on the results of previous studies, the degradation of lignin caused by UV rays and the photooxidation of the CH2 groups into CH(OH) groups caused the yellowing and gradual greying of spruce wood [8], while the sensitivity of some extractives to UV rays could in part explain the tendency of oak surfaces to change their colour connotations [22].

The results of this study are supported by the ANOVA analysis displayed in Table 4 and Table 5. The analysis highlighted the significant effect (Sig. ≤ 0.05) of all three factors (time, treatment, inclination) on colour coordinates in the case of spruce. In the case of oak, the influencing factors did not present a significant effect on the lightness of the samples. Overall, an intense interaction of the exposure time compared to the other two factors, expressed through the Eta Squared coefficient (≥0.50), was noticed for both species.

Table 4.

ANOVA analysis of colour coordinates for spruce samples.

Table 5.

ANOVA analysis of colour coordinates for oak samples.

ANOVA assumes approximate normality of the dependent variable within groups and homogeneity of variances across them. Based on the descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) obtained from the SPSS analysis, these assumptions appeared rea-sonably met, as the variances were comparable and no extreme dispersion was observed. The analysis therefore proceeded under these standard assumptions, which are generally robust to moderate deviations given the sample sizes in this study.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the effectiveness of the oil treatment on the colour stability of two wood species at different inclinations and exposure times was assessed. In the first months of exposure, small variations appeared in the colour tonal scale. The samples exposed vertically showed fewer discolouration compared to the samples with inclined exposure. The oil treatment had a significant impact only on the category of spruce samples having orthogonal exposure. After nine months of exposure, the effectiveness of the oil in preserving the surfaces from decaying processes appeared compromised for the samples with inclined exposure; in fact, it may suggest that another factor, such as fibre orientation, influenced the results. However, the cooked linseed oil, used for decades by local carpenters and artisans, makes wooden surfaces waterproof and enhances their natural grain. Therefore, a frequent application of the siccative oil can represent a possible defensive strategy against the unwanted effects of weathering [23]. A prolongation of exposure time to 24 months would give both researchers and craftsmen a better scope of the effects of linseed oil on preserving the appearance of wood species. Further physical, chemical and microscopic investigations are desirable for a better understanding of other aspects in the complexity of the interaction between atmospheric agents and untreated and treated wood with alternative eco-friendly protective coatings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M. and E.-A.M.S.; methodology, C.M. and F.D.; software, C.M.; validation, C.M. and E.-A.M.S.; formal analysis, C.M.; investigation, C.M. and E.-A.M.S.; resources, C.M.; data curation, F.D.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.; writing—review and editing, E.-A.M.S.; visualisation, C.M.; supervision, E.-A.M.S.; project administration, C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support provided by Transilvania University of Brașov to perform this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kranitz, K.; Sonderegger, W.; Bues, C.T.; Niemz, P. Effects of aging on wood: A literature review. Wood Sci. Technol. 2015, 50, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolvaj, L. Monitoring of Wood Photodegradation by Colour Measurement. In Optical Properties of Wood. Smart Sensors, Measurement and Instrumentation; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropat, M.; Hubbe, M.A.; Laleicke, F. Natural, accelerated, and simulated weathering of wood: A review. BioResources 2020, 15, 9998–10062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topaloglu, E. Effects of natural aging on selected properties of wooden facade elements made of Scots pine and chestnut. Maderas. Cinecia Tecnol. 2023, 25, e1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, W.C. Outdoor Wood Weathering and Protection. In Archaeological Wood: Properties, Chemistry, and Preservation; Advances in Chemistry Series, 225; Rowell, R.M.B., James, R., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüther, P.; Jelle, B.P. Colour changes of wood and wood-based materials due to natural and artificial weathering. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013, 8, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.S. Weathering of Wood. In Handbook of Wood Chemistry and Wood Composites; Rowell, R.M., Ed.; Taylor and Francis CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. Available online: https://www.fpl.fs.usda.gov/documnts/pdf2005/fpl_2005_williams001.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Müller, M.; Rätsch, M.; Schwanninger, M.; Steiner, M.; Zöbl, H. Yellowing and IR-changes of spruce wood as result of UV-irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2003, 69, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinprecht, L. Wood Deterioration, Protection and Maintenance; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9781119106500 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Ozgenc, O.; Okan, O.T.; Yildiz, U.C.; Deniz, I. Wood surface protection against artificial weathering with vegetable seed oils. Bioresurces 2013, 8, 6242–6262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.S.; Knaebe, M.T.; Evans, J.W.; Feist, W.C. Erosion rates of wood during natural weathering: Part III. Effect of exposure angle on erosion rate. Wood Fiber Sci. 2001, 33, 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Schnabel, T.; Zimmer, B.; Petutschnigg, A.J. On the modelling of colour changes of wood surfaces. Eur. J. Wood Prod. 2009, 67, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, C. Traditional Gates in Maramures. Study on the Weathering of Picea abies (L.) and Quercus petraea Liebl Wooden Surfaces. Master’s Dissertation, University of Basilicata, Potenza, Italy, 2018. (In Italian). [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer, J.; Bonura, T.; Nebelsick, A.; Williams, S.; Hunt, C.G. Installation, Care, and Maintenance of Wood Shake and Shingle Siding; General technical report FPL-GTR-202; U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory: Madison, WI, USA, 2011; 13p.

- Vidholdova, Z. Colour changes of wooden shingles treated with pine tar after weathering. In Proceedings of the Book of Abstracts of COST FP1303 Meeting: Design—Application and Aesthetics of Biobased Building Materials, Sofia, Bulgaria, 28 February–1 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Timar, M.C.; Varodi, A.M.; Liu, X.Y. The Influence of Artificial Ageing on Selected Properties of Wood Surfaces Finished With Traditional Materials—An Assessment for Conservation Purposes. Bull. Transilv. Univ. Bras. Ser. II For. Wood Ind. Agric. Food Eng. 2020, 13, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 7724-2:1984; Paints and Varnishes—Colourimetry—Part 2: Colour Measurement. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 1984.

- IBM. SPSS Statistics, Version 23; IBM: Armonk, NY, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-23 (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Giordano, G. Tecnologia del Legno; (Technology of wood, vol.1); Unione Tipografico-Editrice Torinese: Turin, Italy, 1971; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Slabejova, G.; Vidholdova, Z.; Kaloc, J. The Colour Changes of Pinewood After Weathering; Annals of Warsaw University of Life Sciences—SGGW, Forestry and Wood Technology; Warsaw University of Life Sciences: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; No. 96:125:129. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın, M.A.; Can, A.; Tomak, E.D.; Ermeydan, M.A. Weathering of wood under indoor and outdoor environmental conditions. Color. Technol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahri, S.; Belloncle, C.; Charrier, F.; Pardon, P.; Quideau, S.; Charrier, B. UV light impact on ellagitannins and wood surface colour of European oak (Quercus petraea and Quercus robur). Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 253, 4985–4989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirule, D.; Andersone, I.; Kuka, E.; Andersons, B. Recent Research on Linseed Oil Use in Wood Protection—A Review. Sci 2024, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).