Comparison of Plantation Arrangements and Naturally Regenerating Mixed-Conifer Stands After a High-Severity Fire in the Sierra Nevada

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

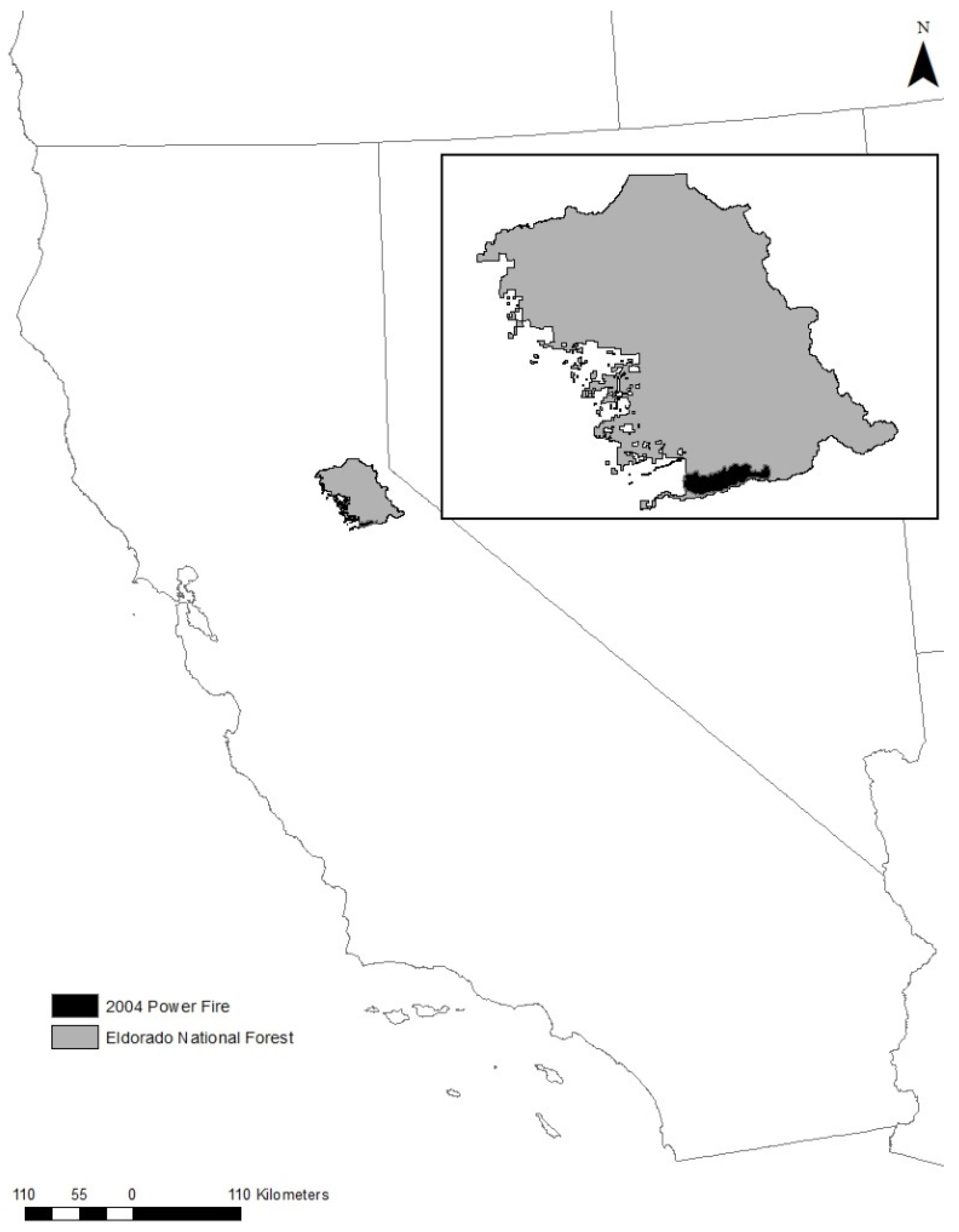

2.1. Study Area

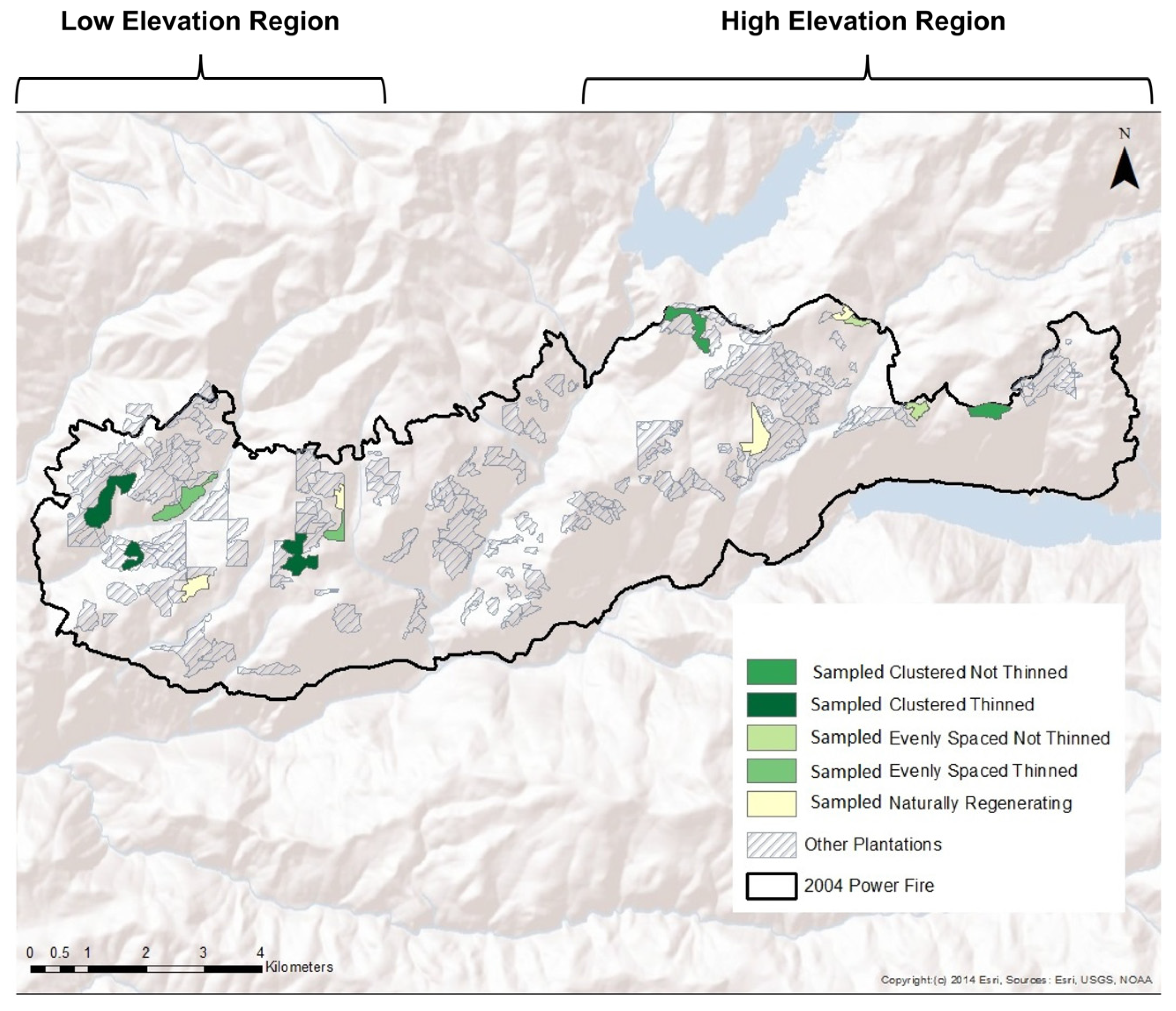

2.2. Site Selection

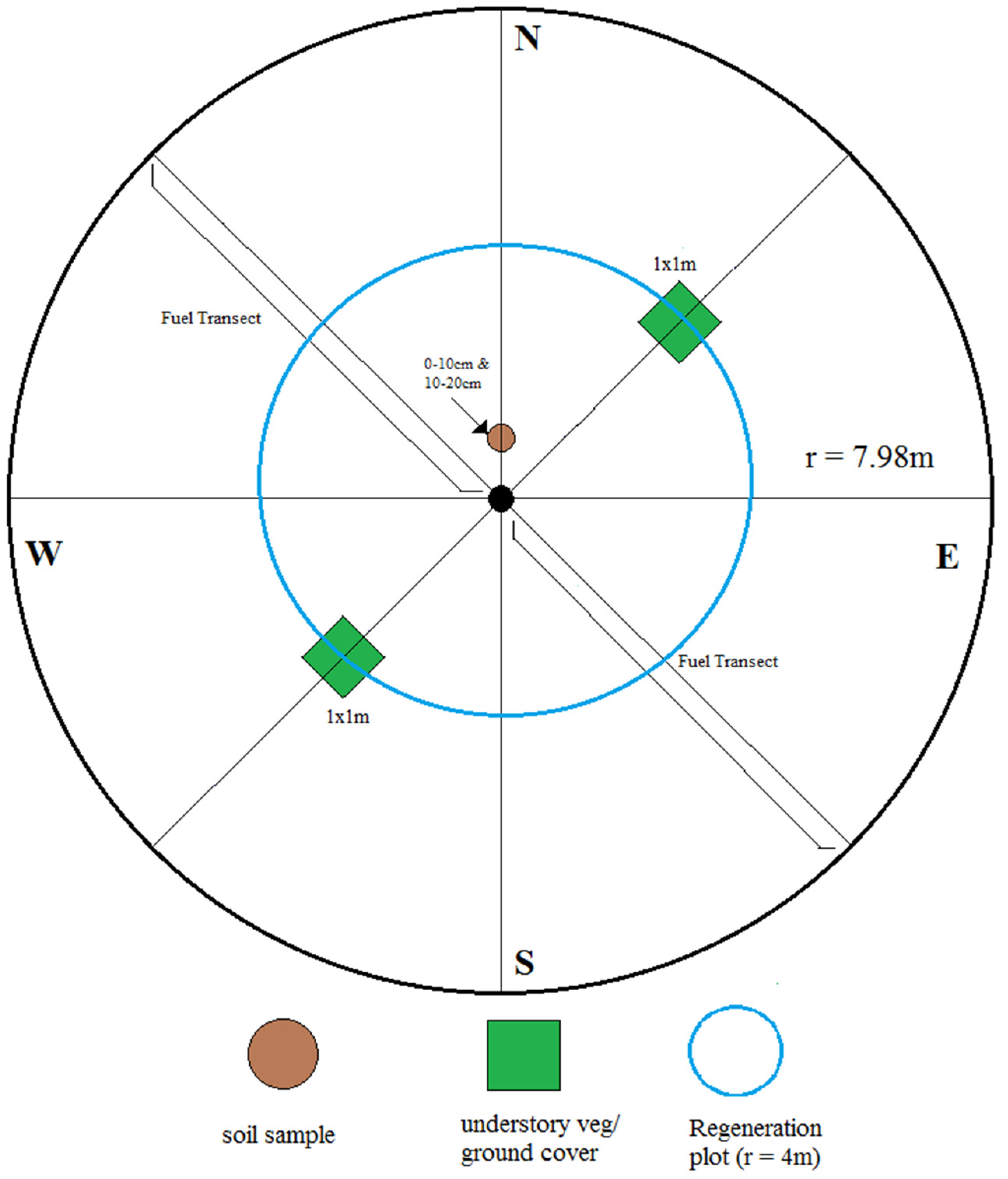

2.3. Field Methods

2.4. Laboratory Methods

2.5. Statistical Methods

3. Results

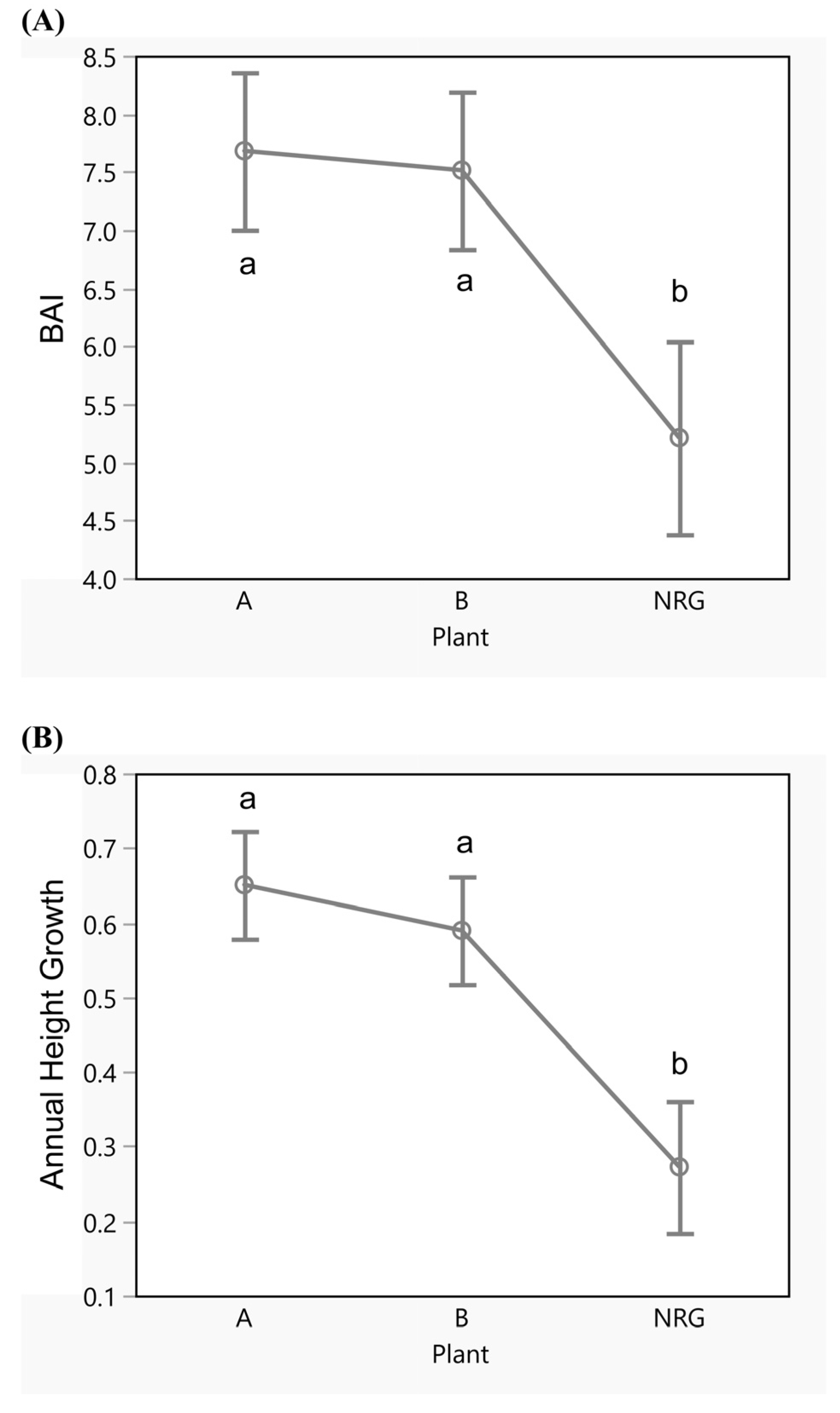

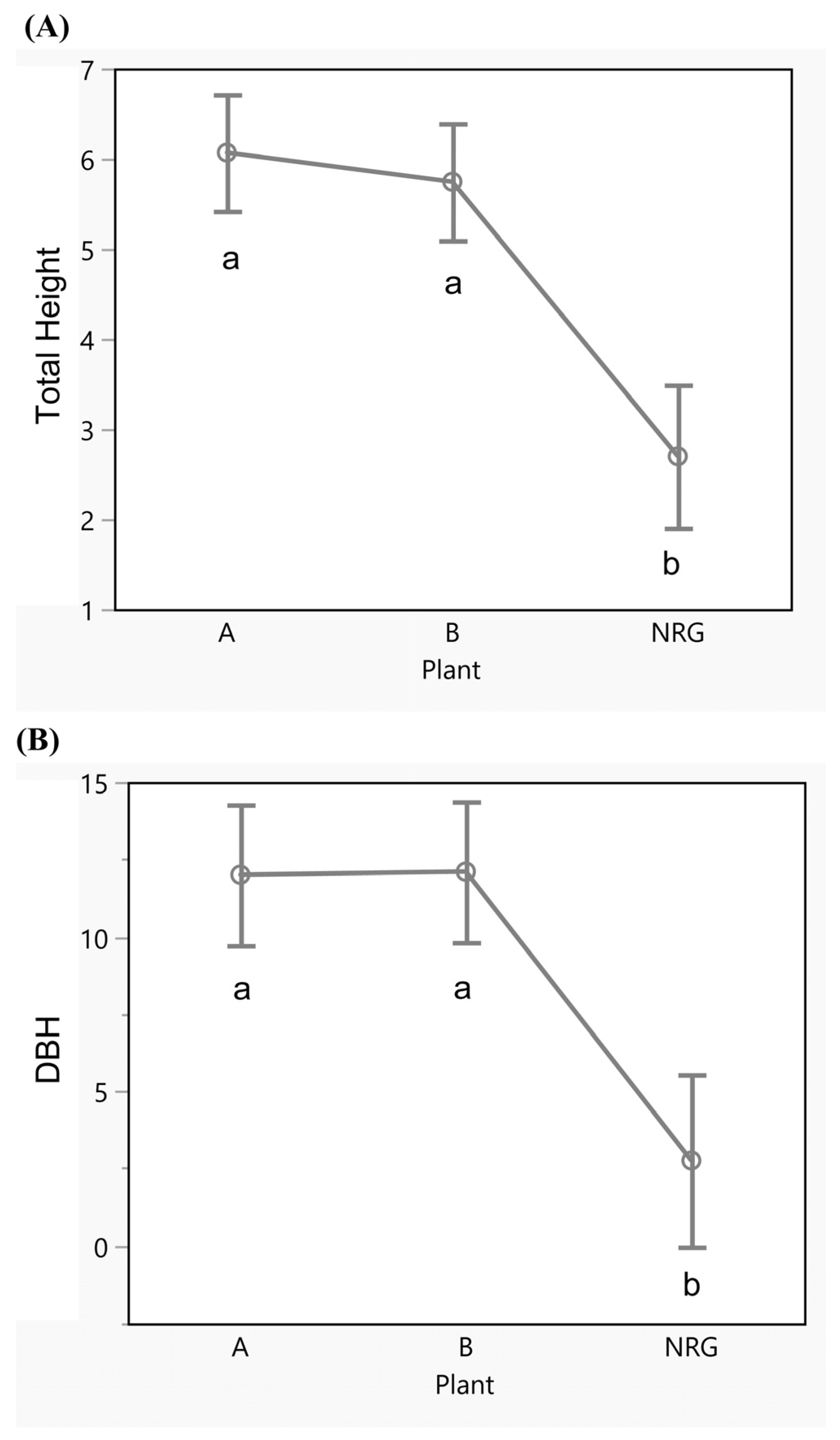

3.1. One-Way ANOVA in the Low- and High-Elevation Regions

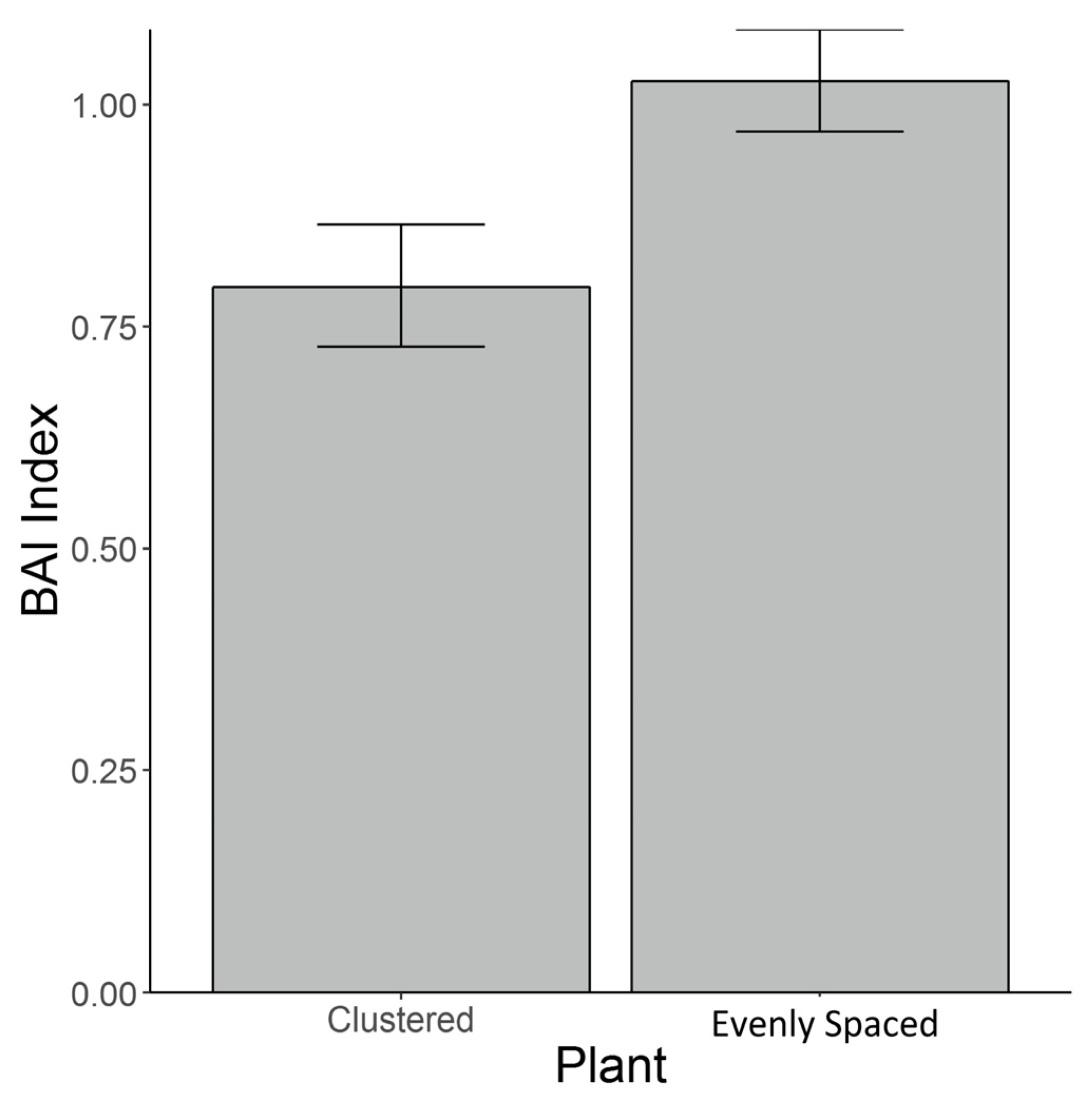

3.2. ANOVA of Only Thinned Plantations in the Low-Elevation Region

3.3. Regression Models

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Evenly spaced plantations appear to maximize growth compared to the clustered arrangement, at least in the short term, which will need to be verified further with future forest monitoring.

- Clustered plantations may enhance structural and spatial heterogeneity across the landscape and potentially provide facilitative effects and thus resilience to extreme climatic stress.

- Shrub management and removal of competing understory vegetation not only promote better growth, but likely also limit fire risk by removing potential ladder fuels.

- Thinning, even as pre-commercial thinning, still continues to promote tree-level productivity and the improved growing space promotes resilience to climatic stress and also limits fire risk [51].

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agee, J.K. Fire Ecology of Pacific Northwest Forests; Island Publisher: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, J.D.; Safford, H.D. Trends in wildfire severity: 1984 to 2010 in the Sierra Nevada, Modoc Plateau, and southern Cascades, California, USA. Fire Ecol. 2012, 8, 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerling, A.L.; Bryant, B.P. Climate change and wildfire in California. Clim. Change 2007, 87 (Suppl. S1), 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.M.; Roller, G.B. Early forest dynamics in stand-replacing fire patches in the northern Sierra Nevada, California, USA. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 1801–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, M.P.; Stevens, J.T.; Greene, D.F.; Coppoletta, M.; Knapp, E.E.; Latimer, A.M.; Restaino, C.M.; Restaino, C.M.; Tompkins, R.E.; Welch, K.R.; et al. Tamm Review: Reforestation for resilience in dry western U.S. forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 432, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA Forest Service. Power Fire Reforestation Project; USDA Forest Service, Eldorado National Forest: Placerville, CA, USA, 2014.

- Churchill, D.J.; Larson, A.J.; Dahlgreen, M.C.; Franklin, J.F.; Hessburg, P.F.; Lutz, J.A. Restoring forest resilience: From reference spatial patterns to silvicultural prescriptions and monitoring. For. Ecol. Manag. 2013, 291, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, M.P.; Stine, P.A.; O’Hara, K.; Zielinski, W.J.; Stephens, S.L.; Service, F.; Hara, K.O. An Ecosystem Management Strategy for Sierran Mixed-Conifer Forests; General Technical Reports, PSW-GTR-220; USDA Forest Service: Albany, CA, USA, 2009.

- Chamberlain, C.P.; Bartl-Geller, B.N.; Cansler, C.A.; North, M.P.; Meyer, M.D.; van Wagtendonk, L.; Redford, H.E.; Kane, V.R. When do contemporary wildfires restore forest structures in the Sierra Nevada. Fire Ecol. 2024, 20, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchesneau, R.; Lesage, I.; Messier, C.; Morin, H. Effects of light and intraspecific competition on growth and crown morphology of two size classes of understory balsam fir saplings. For. Ecol. Manag. 2001, 140, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, P.M. Forest Regeneration and Seedling Growth from Five Major Cutting Methods in North-Central California; Research Paper PSW-115; Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station: Riverside, CA, USA, 1976; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Royce, E.B.; Barbour, M.G. Mediterranean climate effects. I. Conifer water use across a Sierra Nevada ecotone. Am. J. Bot. 2001, 88, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tappeiner, J.C.; McDonald, P.M. Regeneration of Sierra Nevada forests. In Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project Final Report to Congress: Status of the Sierra Nevada; USGS Publications Warehouse: Reston, VA, USA, 1996; Volume 3, pp. 501–513. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W.; Meade, R.; Leon, R.; Hyink, D.; Miller, R. Planting density and tree-size relations in coast Douglas-fir. Can. J. For. Res. 1998, 28, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo, A.; McIntire, E.J.B. Under strong niche overlap conspecifics do not compete but help each other to survive: Facilitation at the intraspecific level. J. Ecol. 2011, 99, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, S.M.; Sieg, C.H.; Sánchez Meador, A.J.; Fulé, P.Z.; Iniguez, J.M.; Baggett, L.S.; Fornwalt, P.J.; Battaglia, M.A. Spatial patterns of ponderosa pine regeneration in high-severity burn patches. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 405, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, M. Combined effects of shade and drought on tulip poplar seedlings: Trade-off in tolerance or facilitation? Nord. Soc. Oikos 2000, 90, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, S.W. The foundational role of mycorrhizal networks in self-organization of interior Douglas-fir forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2009, 258, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, T.A.; Taylor, A.H. Fire and persistence of montane chaparral in mixed conifer forest landscapes in the northern Sierra Nevada, Lake Tahoe Basin, California, USA. J. Torrey Bot. Soc. 2005, 132, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, W.H.; Mcbride, J.R.; Rowntree, R. Revegetation after four stand replacing fires in the Lake Tahoe Basin. Madrono 1998, 45, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet, V.H.; Schoettle, A.W.; Shepperd, W.D. Postfire environmental conditions influence the spatial pattern of regeneration for Pinus ponderosa. Can. J. For. Res. 2005, 35, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, P.M.; Fiddler, G.O. Twenty-Five Years of Managing Vegetation in Conifer Plantations in Northern and Central California: Results, Application, Prin-Ciples, and Challenges; General Technical Reports PSW-GTR_231; USDA Forest Service: Albany, CA, USA, 2010. Available online: http://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/37965 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Zhang, J.; Oliver, W.W.; Busse, M.D. Growth and development of ponderosa pine on sites of contrasting productivities: Relative importance of stand density and shrub competition effects. Can. J. For. Res. 2006, 2438, 2426–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobziar, L.N.; Mcbride, J.R.; Stephens, S.L. The efficacy of fire and fuels reduction treatments in a Sierra Nevada pine plantation. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2009, 18, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, I.; Pawlikowski, N.; Chhin, S.; Premer, M.; Zhang, J. Modeling juvenile stand development and fire risk of post fire planted-forests under variations in thinning and fuel treatments using FVS-FFE. Forests 2023, 14, 1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R. Bailey’s Ecoregions and Subregions of the United States, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands; Forest Service Research Data Archive: Ft. Collins, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service. Final Environmental Impact Statement Power Fire Reforestation Project; U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service: Missoula, MT, USA, 2017.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service. Record of Decision. In Sierra Nevada Forest Plan Amendment—Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement; U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Forest Service: Missoula, MT, USA, 2004; p. 72. Available online: http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/r5/landmanagement/planning/?cid=STELPRDB5349922 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Speer, J.H. Fundamentals of Tree Ring Research; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cybis Electronic. CDendro and CooRecorder. 2018. Available online: https://www.cybis.se/forfun/dendro/index.htm (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Bunn, A.G. A dendrochronology program library in R (dplR). Dendrochronologia 2008, 26, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R; RStudio Team: Boston, MA, USA, 2018; Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- SAS Institute Inc. JMP; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, SC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nyland, R.D. Silviculture: Concepts and Applications, 2nd ed.; Waveland Press, Inc.: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2002; 682p. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, I.; Chhin, S.; Zhang, J. Fire and forest management in montane forests of the northwestern States and California, USA. Fire 2019, 2, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterner, S.; Aslan, C.; Best, R.; Chaudhry, T. Forest management effects on vegetation regeneration after a high severity wildfire: A case study in the southern Cascade range. For. Ecol. Manag. 2022, 520, 120394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertness, M.D.; Callaway, R.M. Positive interactions in communities. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1994, 9, 191–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmied, S.; Kappen, J.; del Rio, M.; Moser, W.K.; Gundale, M.J.; Hilmers, T.; Ambs, D.; Uhl, E.; Pretzsch, H. Positive mixture effects in pine-oak forests during drought are context-dependent. Plant Biol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlman, G.N.; North, M.P.; Safford, H.D. Shrub removal in reforested post-fire areas increases native plant species richness. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 374, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinnis, T.W.; Keeley, J.E.; Stephens, S.L.; Roller, G.B. Fuel buildup and potential fire behavior after stand-replacing fires, logging fire-killed trees and herbicide shrub removal in Sierra Nevada forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 260, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayman, R.B.; North, M.P. Initial response of a mixed-conifer understory plant community to burning and thinning restoration treatments. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 239, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premer, M.; Chhin, S.; Zhang, J. Local testing and calibration of species-specific competition indices in Sierran mixed-conifer forests: Application transfer to evolving objectives. Can. J. For. Res. 2021, 51, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, K.R.; Safford, H.D.; Young, T.P. Predicting conifer establishment 5–7 years after wildfire in middle elevation yellow pine and mixed conifer forests of the North American Mediterranean-climate zone. Ecosphere 2016, 7, e01609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundel, P.W.; Keeley, J.E. Dispersal Limitation Does Not Control High Elevational Distribution of Alien Plant Species in the Southern Sierra Nevada, California. Nat. Areas J. 2016, 36, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Western Regional Climate Center. Climate of California. Western Regional Climate Center, 2018. Available online: https://wrcc.dri.edu (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Klinger, R.; Underwood, E.C.; Moore, P.E. The role of environmental gradients in non-native plant invasion into burnt areas of Yosemite National Park, California. Divers. Distrib. 2006, 12, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wathen, S.; Thorne, J.H.; Holguin, A.; Schwartz, M.W. Estimating the spatial and temporal distribution of species richness within Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chase, C.W.; Kimsey, M.J.; Shaw, T.M.; Coleman, M.D. The response of light, water, and nutrient availability to pre-commercial thinning in dry inland Douglas-fir forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 363, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayan, D.R.; Luers, A.L.; Franco, G.; Hanemann, M.; Croes, B.; Vine, E. Overview of the California climate change scenarios project. Clim. Change 2008, 2008, S1–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhin, S.; Wang, G.G. Growth of white spruce, Picea glauca, seedlings in relation to microenvironmental conditions in a forest-prairie ecotone of southwestern Manitoba. Can. Field Nat. 2007, 121, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ritchie, M.W.; Maguire, D.A.; Oliver, W.W. Thinning ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa) stands reduces mortality while maintaining stand productivity. Can. J. For. Res. 2013, 43, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasperse, L.; Collins, B.M.; Coppoletta, M.; Merriam, K.; Stephens, S.L. Drivers of fire severity in repeat fires: Implications for mixed-conifer forests in the Sierra Nevada, California. Fire Ecol. 2025, 21, 46. [Google Scholar]

| StandID | Plantation Arrangement | Thinned | # of Plots | Slope (Degrees) | Elevation (m) | Aspect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Low-Elevation Region | ||||||

| A102 | Clustered (A) | Yes | 5 | 19.4 | 1416.6 | 255.6 |

| A137 | Clustered (A) | Yes | 5 | 26.6 | 1427.4 | 121.0 |

| A78 | Clustered (A) | Yes | 5 | 12.4 | 1555.0 | 90.2 |

| B139 | Evenly Spaced (B) | Yes | 5 | 29.2 | 1358.4 | 106.0 |

| B140 | Evenly Spaced (B) | Yes | 5 | 28.6 | 1355.9 | 157.0 |

| B82 | Evenly Spaced (B) | Yes | 5 | 15 | 1434.8 | 134.6 |

| NRG147 | Natural Regeneration (NRG) | NA | 7 | 14.7 | 1460.6 | 114.6 |

| NRG164 | Natural Regeneration (NRG) | NA | 8 | 6.9 | 1525.3 | 71.9 |

| (b) High-Elevation Region | ||||||

| A217 | Clustered (A) | No | 5 | 13.2 | 1961.4 | 122.2 |

| A25 | Clustered (A) | No | 5 | 9.4 | 1984.8 | 200.2 |

| B13 | Evenly Spaced (B) | No | 5 | 10.4 | 1970.9 | 126.4 |

| B24 | Evenly Spaced (B) | No | 5 | 10.0 | 1939.6 | 182.4 |

| NRG17 | Natural Regeneration (NRG) | NA | 5 | 15.6 | 2011.4 | 121.6 |

| NRG302 | Natural Regeneration (NRG) | NA | 5 | 15.0 | 1794.9 | 200.4 |

| StandID | Plantation Arrangement | Thinned | ABCO | ABMA | CADE | PIJE | PIPO | PILA | PSME | Hardwoods | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Low Elevational Region | |||||||||||

| A102 | Clustered (A) | Yes | 0 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 220 | 0 | 0 | 70 | 350 |

| A137 | Clustered (A) | Yes | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 290 | 10 | 0 | 390 | 700 |

| A78 | Clustered (A) | Yes | 0 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 260 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 280 |

| B139 | Evenly Spaced (B) | Yes | 0 | 0 | 60 | 0 | 360 | 0 | 70 | 190 | 680 |

| B140 | Evenly Spaced (B) | Yes | 0 | 0 | 30 | 0 | 370 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 440 |

| B82 | Evenly Spaced (B) | Yes | 0 | 0 | 40 | 0 | 290 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 380 |

| NRG147 | Natural Regeneration (NRG) | No | 7 | 0 | 821 | 0 | 1550 | 14 | 0 | 7 | 2399 |

| NRG164 | Natural Regeneration (NRG) | No | 56 | 0 | 519 | 0 | 1344 | 56 | 13 | 13 | 2001 |

| (b) High Elevation Region | |||||||||||

| A217 | Clustered (A) | No | 10 | 120 | 0 | 1120 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 170 | 1470 |

| A25 | Clustered (A) | No | 20 | 0 | 50 | 480 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 550 |

| B13 | Evenly Spaced (B) | No | 0 | 30 | 60 | 1450 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1540 |

| B24 | Evenly Spaced (B) | No | 0 | 70 | 0 | 110 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 200 |

| NRG17 | Natural Regeneration (NRG) | No | 10 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 120 |

| NRG302 | Natural Regeneration (NRG) | No | 0 | 0 | 30 | 20 | 250 | 10 | 0 | 240 | 550 |

| Variable | pTRT | pstand |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Low-Elevation Region | ||

| Regen/ha | 0.0033 ** | <0.0001 |

| Shrub % | 0.0507 * | <0.0001 |

| Shannon’s diversity index | 0.4873 | <0.0001 |

| Species richness | 0.2443 | <0.0001 |

| Shrub height | 0.0877 * | <0.0001 |

| DBH | 0.0020 ** | <0.0001 |

| Total height | 0.0008 ** | <0.0001 |

| TPH before thinning | 0.8268 | <0.0001 |

| TPH after thinning | 0.0054 ** | <0.0001 |

| BAI before thinning (2013–2014) | 0.0039 ** | <0.0001 |

| Annual height growth before thinning | 0.0009 ** | <0.0001 |

| (b) High-Elevation Region | ||

| Regen/ha | 0.5735 | <0.0001 |

| Shrub % | 0.9286 | <0.0001 |

| Shannon’s diversity index | 0.8787 | <0.0001 |

| Species richness | 0.8770 | <0.0001 |

| Shrub height | 0.5111 | <0.0001 |

| DBH | 0.2926 | <0.0001 |

| Total height | 0.5332 | <0.0001 |

| Variable | Type | pplant | pstand | pplot |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAI 2016 | Increment | 0.8892 | 0.4251 | 0.0020 |

| BAI thinning index | Index | 0.0610 * | 0.8063 | 0.00001 |

| Annual height growth after 2016 | Increment | 0.4833 | 0.2912 | 0.0473 |

| Annual height index | Index | 0.7759 | 0.3866 | <0.0001 |

| Dependent Variable | Explanatory Variable with Coefficients | Adj R2 |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Low-Elevation Region | ||

| BAI 2013–2016 | 1119.421 + (−902.9819 * TrtNRG) | 0.6616 |

| BAI before thinning | 1126.333 + (−889.7403 * TrtNRG) | 0.5446 |

| BAI after thinning | 1980.265 + (−1680.2667 * TrtNRG) | 0.7024 |

| Height growth 2013–2016 | 0.3482 + (0.1482 * ShrubHeight) + (−0.1410 * TrtNRG) | 0.6423 |

| Height growth before thinning | 0.3270 + (0.0008 * Aspect) + (−0.1745 * TrtNRG) | 0.6390 |

| Height growth after thinning | 0.4719 + (−0.1692 * TrtNRG) | 0.5258 |

| (b) High-Elevation Region | ||

| BAI 2013–2016 | −494.487 + (−6.359 * ShrubPercent) + (661.0129 * ShrubHeight) + (−13.5391 * SS.ABCO) + (−5.309 * SS.CADE) + (7.2601 * SS.YP) + (28.9281 * SS.FIR) + (381.0244 * FreqYP) | 0.7982 |

| Height growth 2013–2016 | 0.044 + (−0.0057 * SS.ABCO) + (−0.0017 * SS.CADE) + (0.0093 * SS.FIR) + (0.2591 * FreqYP) | 0.7367 |

| Dependent Variable | Explanatory Variable with Coefficients | Adj R2 |

|---|---|---|

| (a) Low-Elevation Region | ||

| BAI 2013–2016 | −3926.578 + (−9.7259 * ShrubPercent) + (−221.2146 * Rich) + (−0.3151 * PreTPH) | 0.3974 |

| BAI before thinning | 3494.755 + (−12.4837 * ShrubPercent) + (−255.1546 * Rich) + (−0.3607 * PreTPH) + (1054.5197 * FreqYP) | 0.4227 |

| BAI after thinning | 6881.3828 + (−18.3104 * ShrubPercent) + (−346.6670 * Rich) + (−0.5414 * PreTPH) | 0.3560 |

| Height growth 2013–2016 | 0.607 + (0.000013 * RegenCount) | 0.0100 |

| Height growth before thinning | 0.602 + (0.000015 * RegenCount) | 0.1102 |

| Height growth after thinning | 0.727 + (−0.000047 * PreTPH) | 0.1711 |

| (b) High-Elevation Region | ||

| BAI 2013–2016 | −616.677 + (−4.9004 * ShrubPercent) + (554.8441 * ShrubHeight) + (9.9389 * SS.PIJE) + (−4.3142 * SS.PILA) + (−17.0197 * SS.ABCO) + (8.8627 * SS.ABMA) + (17.7243 * SS.FIR) + (836.492 * FreqYP) | 0.9497 |

| Height growth 2013–2016 | −0.046 + (0.0014 * SS.PIJE) + (−0.0022 * SS.ABCO) + (0.0050 * SS.ABMA) + (0.4129 * FreqYP) | 0.8473 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Allen, I.; Chhin, S.; Zhang, J.; Premer, M. Comparison of Plantation Arrangements and Naturally Regenerating Mixed-Conifer Stands After a High-Severity Fire in the Sierra Nevada. Forests 2025, 16, 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101506

Allen I, Chhin S, Zhang J, Premer M. Comparison of Plantation Arrangements and Naturally Regenerating Mixed-Conifer Stands After a High-Severity Fire in the Sierra Nevada. Forests. 2025; 16(10):1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101506

Chicago/Turabian StyleAllen, Iris, Sophan Chhin, Jianwei Zhang, and Michael Premer. 2025. "Comparison of Plantation Arrangements and Naturally Regenerating Mixed-Conifer Stands After a High-Severity Fire in the Sierra Nevada" Forests 16, no. 10: 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101506

APA StyleAllen, I., Chhin, S., Zhang, J., & Premer, M. (2025). Comparison of Plantation Arrangements and Naturally Regenerating Mixed-Conifer Stands After a High-Severity Fire in the Sierra Nevada. Forests, 16(10), 1506. https://doi.org/10.3390/f16101506