1. Introduction

Thousands of wildfires are registered every year worldwide [

1,

2], and the extreme behavior of fires has exceeded firefighting services capacities on many occasions in recent years [

3]. Wildfires are complex phenomena linked to land management, local culture, and global warming, driven by the growing climate crisis, which triggers a set of consequences affecting the environment and everything from human health to biodiversity [

4,

5], with rural communities being especially vulnerable (Graus et al., 2024). Recent research on catastrophic wildland fires in the last decades in different regions of the world coincide in linking the frequency and exacerbation of fires with rural depopulation and abandonment of agricultural and forestry uses of the territory [

6,

7]. Among wildland fires, forest fires are considered one of the most dangerous hazards to the environment around the world [

8]. In this sense, the European Union (EU) rural policies are considered a major driver of landscape change over time in Europe, in particular in rural landscapes in Southern Europe, which have become increasingly exposed to forest fires in recent decades [

9].

The European Mediterranean region is considered a highly populated and a high fire risk area with nearly 200 million people living in just five countries (France, Italy, Greece, Portugal, and Spain) [

10]. Forest fires in the Mediterranean region have historically had a human cause [

11,

12], which reduced the number of fires caused by lightning or other factors of natural origin to a smaller number. However, there is currently a growing concern about the evolution of their regime and characteristics. Among other factors, the progressive abandonment of traditional rural activities and the depopulation of rural areas are becoming increasingly important [

13,

14,

15,

16], since their effects on land use can influence both the prevention and suppression of forest fires [

9]. Thus, the increase in the number of fires, concentrated in southern European countries, is associated with the socioeconomic changes of recent decades: depopulation of rural areas and concentration of population in urban areas [

17,

18,

19]. For a long time, the demographic evolution in Europe has faced important differences by countries and inside them [

20]: large congested cities and depopulated rural areas, with strong internal imbalances and in serious population decline [

21,

22].

Widespread depopulation of rural areas over the past decades in Spain has led to the encroachment of shrubs and trees on former farmland. In addition, the expanding forests are now denser than before because fewer trees are logged and livestock no longer roam freely [

23]. Gallardo et al. [

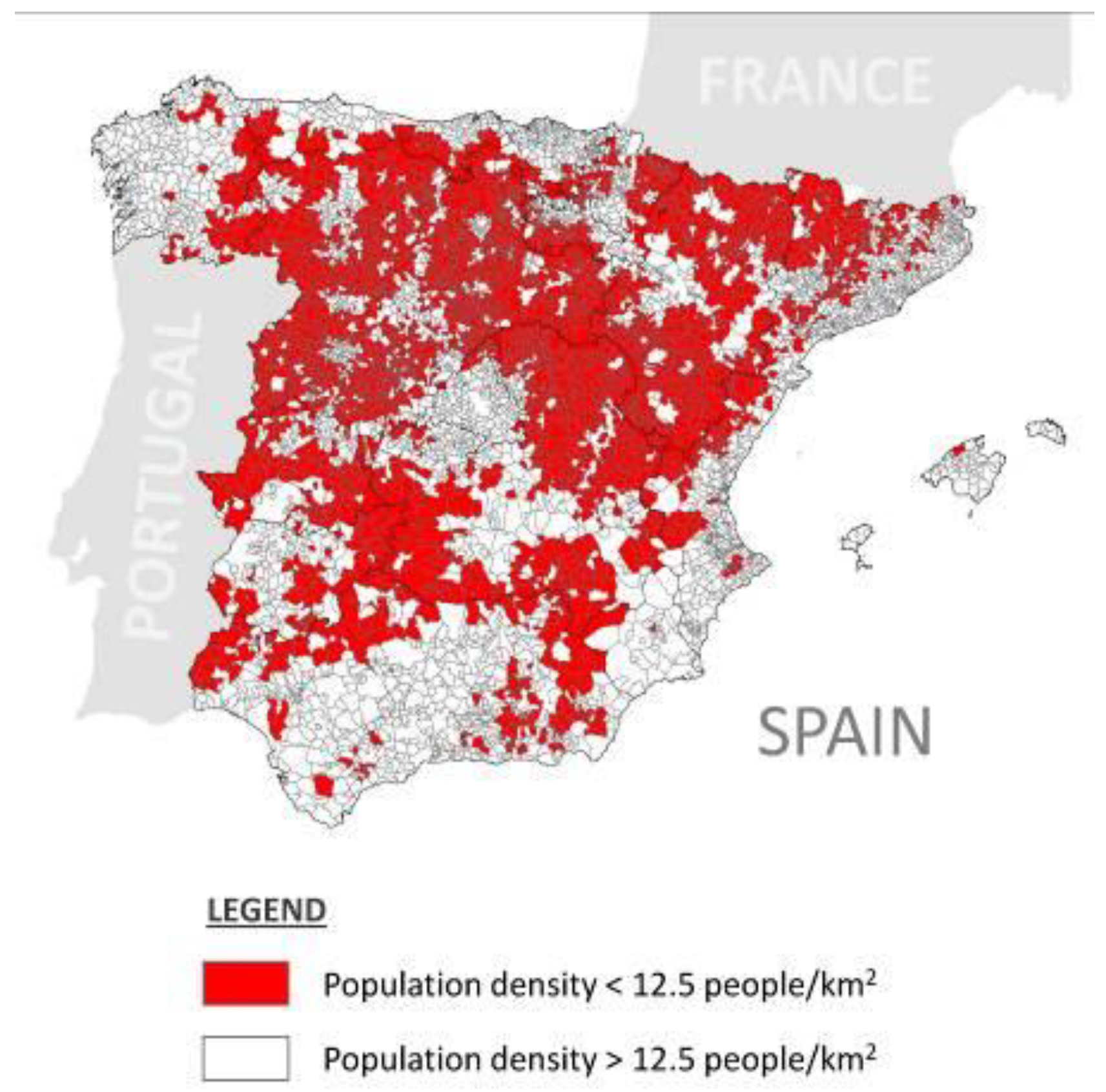

24] found a relationship with the expansion of forests where, additionally, overlapping processes of afforestation and reforestation programs have occurred. Currently, sparsely populated areas, i.e., with less than 12.5 inhabitants per square kilometer, occupy approximately 49% of the territory (

Figure 1), where only 2.7% of the population lives, while 80% of the population is concentrated in urban areas, which account for only 20% of the territory [

25]. This fact has coined the expression ‘The emptied Spain’ which includes rural municipalities, mainly in the Autonomous Communities of Extremadura, Castilla la Mancha, Castilla y León, Aragón, Galicia, Asturias, and, to a lesser extent, others, where the population is very low and has decreased in recent years. The seriousness of this situation, which will continue to intensify, has become an environmental problem [

26]. Indeed, changes in forest management due to other policies’ influence and rural depopulation may be more relevant for fire activity than changes in climate change [

27]. Better coordination between the different administrations is needed, reorienting their actions toward more integrated and sustainable territorial and social development strategies [

28].

For some years now, several researchers have been stressing the need to include socioecological approaches to deal with forest fire management, including social vulnerability to fires [

13,

29,

30,

31]. Because prevention and firefighting may require a multisector vision and implementation of novel solutions, decisionmakers may be required to shift towards a collaborative and holistic vision [

32,

33]. In this sense, the literature points out the influence of some social factors influencing forest fires such as the age of population groups, housing typology, roads, and other infrastructure density, or economic and educational level [

34,

35,

36]. Surprisingly, to our knowledge, the possible relationship with the existence of some basic services in rural areas such as primary schools has not been yet studied, despite its presence in the territory is given or influences other socioeconomic variables [

37,

38] potentially linked to forest fire risk increase and social vulnerability to forest fires [

29,

31,

35,

36]. The closure of small rural schools is becoming a matter of concern throughout Europe and many other regions worldwide [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Schools are considered necessary for a municipality, as their closure may lead to the loss of function and stability of the community [

38,

44], and entails the use of daily transport for children, which leads to children and young people leaving their localities and going to more populated localities.

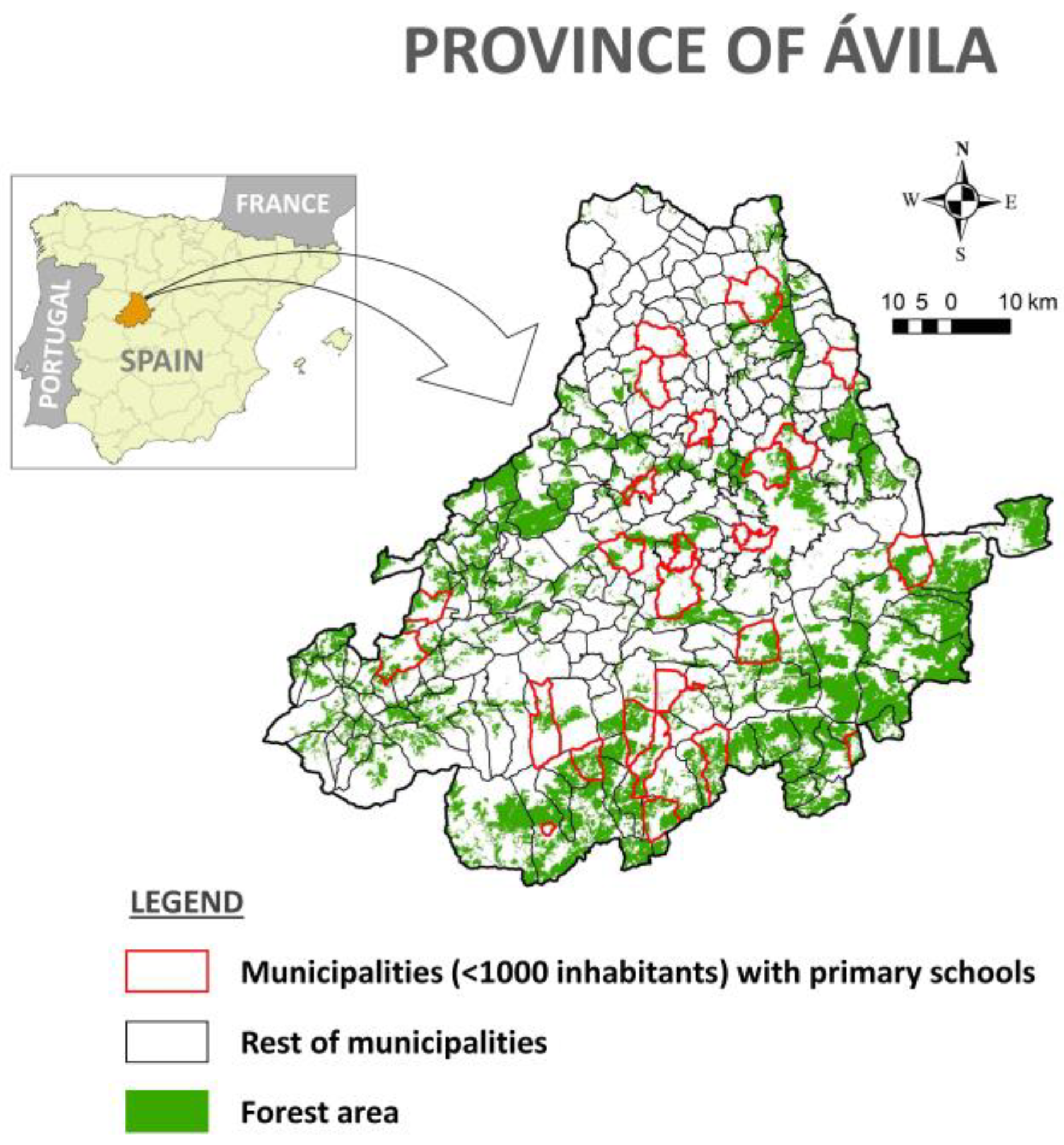

This paper aims to explore a potential relationship between the distribution of primary schools and forest fires in rural areas. Our main hypothesis is that the presence of rural schools could be an indirect indicator of non-measurable symbolic aspects of the social dynamism of a municipality [

45,

46,

47] that, perhaps, are not reflected in other socioeconomic factors more frequently considered (e.g., mean age, unemployment rate, economic activities) in forest fires research. Our research focuses on the province of Ávila (autonomous community of Castilla y León), as it is one of the inland provinces of Spain affected by depopulation processes and where more forest fires are recorded year after year. A large portion of the large fires in the Central System are registered in this province, which constitute one of the worst environmental and economic threats to rural communities [

48,

49].

3. Results

In total, 30 municipalities were excluded from the statistical analysis because they had more than 1000 inhabitants (

n = 13) and/or lacked tree forest area (

n = 27). The remaining 218 municipalities of the province are characterized by average values of 198 inhabitants in each municipality (SD = 198.95) and population density decreased a mean value of 4.31 people (SD = 6.84). About orography, the mean altitude of the municipalities of Ávila is 1126.8 m (SD = 249.03) and they have a range of slopes of 15.95% (SD = 13.54). On average, each municipality has a density of 0.49 km of road infrastructure per square kilometer of territory, 6.5 hectares of forest area (SD = 8.16), and 0.11 terrestrial resources for fighting forest fires (SD = 0.44). Finally, during the analyzed period, each municipality accumulated an average of 4.35 forest fires (SD = 10.29) and 31.39 hectares (SD = 190.84) of forest area were burned (

Table 3). This makes an average of approximately 1.30 hectares burned per year.

However, when the average values of these variables are analyzed considering the separation into two groups of municipalities, GROUP 1, which refers to the municipalities that have SCHOOL (

n = 26), and GROUP 2, which represents the municipalities that do not have SCHOOL (

n = 192), some noticeable differences can be seen. On average, the villages where a SCHOOL is located have 3.3 times more inhabitants (M = 519.12, SD = 219.03) than the villages in Group 2 (M = 154.74, SD = 150.90,

Table 3), and the population density decrease is almost twice as much in GROUP 1 (M = −6.85, SD = 16.21) as in GROUP 2 (M = −3.97, SD = 4.22). The average age is 5 years lower in GROUP 1 (M = 52.97, SD = 3.87), which also has a higher unemployment rate (M = 8.11, SD = 4.30) than in GROUP 2 (M = 5.75, SD = 4.30), but twice the number of agricultural holdings (M = 50.08, SD = 36.90) than in GROUP 2 (M = 25.70, SD = 19.95).

The Mann–Whitney

U test showed a statistically significant difference in POP96 values (

U = 477.5,

p < 0.001) between both groups (

Table 4), but not in DIFDENS (

U = 1942.0,

p = 0.066) between the years 2023 and 1996. Other statistically significant differences between GROUP 1 and GROUP 2 were found in AGE50–59 (

U = 455.0,

p < 0.001) and MEAGE (

U = 1216.5,

p < 0.001).

Road density was 24% lower in GROUP 2 municipalities, and terrestrial resources for fighting forest fires seem to be mostly located in GROUP 1 municipalities. In both cases, the difference in the distribution of these infrastructures and services was statistically significant between groups: ROADENS (U = 1541.0, p = 0.002) and TERRES (U = 2044.0, p < 0.001). Other statistically significant differences between GROUP 1 and GROUP 2 were found in AGRICU (U = 1300.5, p < 0.001) and TERRES (U = 2044.0, p < 0.001). On the other hand, the orographic variables did not show statistically significant differences between the municipalities included in GROUP 1 and those belonging to GROUP 2: ALTITU (U = 2080.0, p = 0.169) and SLOPE (U = 2010.0, p = 0.107).

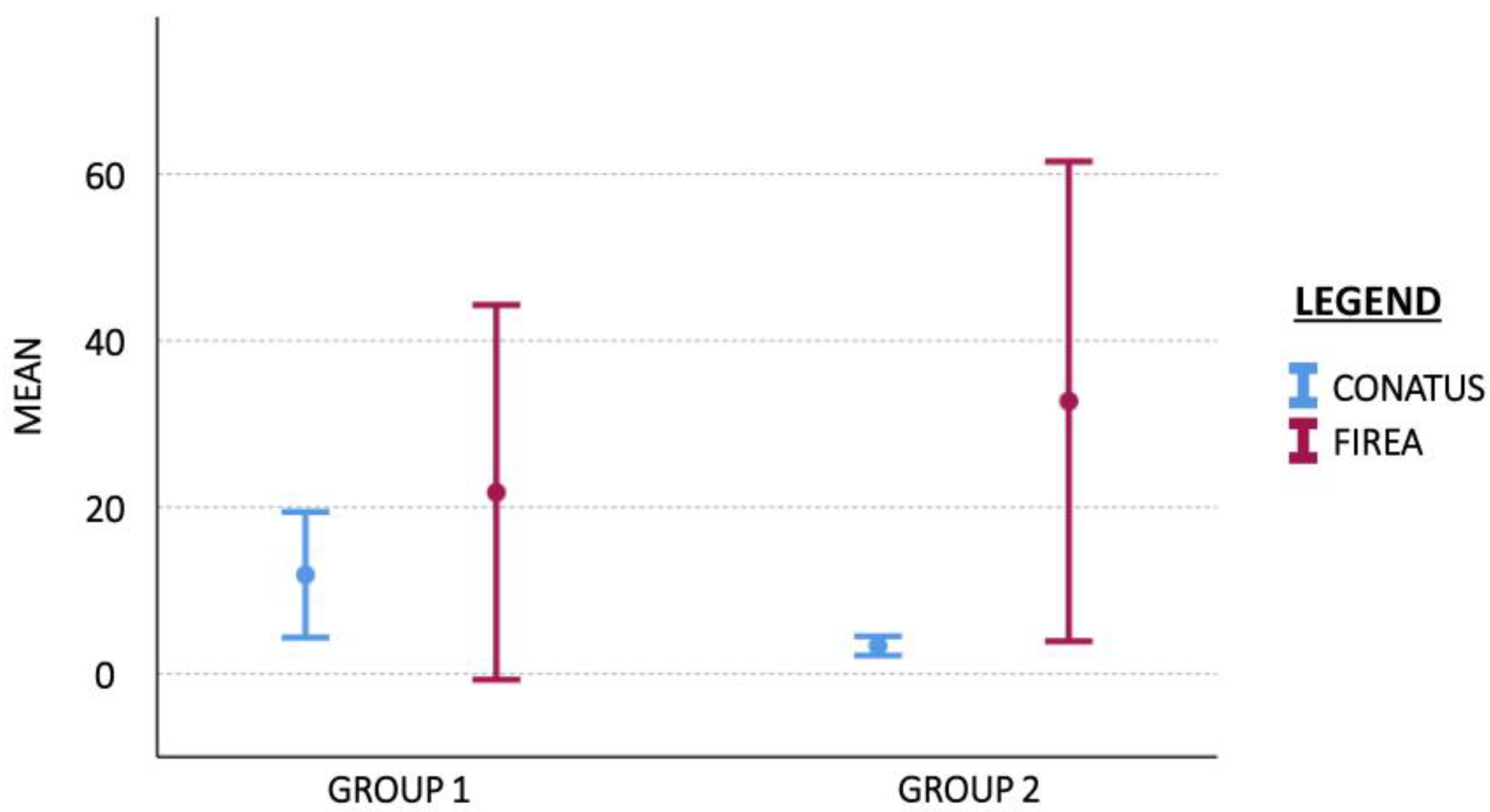

In relation to forest tree cover, the average value per municipality is 41% higher in GROUP 1 (M = 8.71, SD = 7.25 vs. M = 6.18, SD = 8.26), and this difference was statistically significant as shown by the Mann–Whitney U test (

U = 1854.0,

p = 0.033). Differences in the number of CONATUS (

U = 1832.5,

p = 0.005) and the mean value of forest area burned between groups, FIREA (

U = 1975.5,

p = 0.035), were also statistically significant. The average number of CONATUS was much higher in GROUP 1 (M = 11.88, SD = 18.70) compared to GROUP 2 (M = 3.35, SD = 8.12), although the mean value of forest area burned is higher in GROUP 2 municipalities (M = 32.70, SD = 202.38) compared to municipalities in GROUP 1 (M = 21.77, SD = 55.70). In fact, the largest forest fires during the study period took place in municipalities that do not have SCHOOL (

Figure 3). However, no statistically significant differences were found between the two groups and the variables that estimate fire risk (RISK5, RISK6, RISK7, RISK8, RISK9, and RISK10).

Finally, the GLM as a whole was found to be significant in explaining variations of FIREA between groups. In particular, the model showed statistically significant main effects for SCHOOL (χ

2 = 13.307,

p-value < 0.001), CONATUS (χ

2 = 48.283,

p-value < 0.001), DIFDENS (χ

2 = 12.474,

p-value < 0.001), and SLOPE (χ

2 = 17.512,

p-value < 0.001) (

Table 5). In this sense, it is worth noting that FIREA was 50% higher in GROUP 2 (M = 32.70, SD = 202.38) than in GROUP 1 (M = 21.77, SD = 55.70). GROUP 1 comprises the municipalities in which there are rural schools (SCHOOL), despite the mean number of CONATUS (M = 11.88, SD = 18.70 vs. M = 3.35, SD = 8.12) being approximately 250% higher than in GROUP 2, and SLOPE also being higher than in GROUP 2 (M = 20.25, SD = 16.02 vs. M = 15.38, SD = 13.11). Depopulation speed (DIFDENS) was approximately 100% higher in GROUP 1 (M = −6.86, SD = 16.21 vs. M = −3.97, SD = 4.22). At a lower level, the model also showed statistically significant main effects for the influence of the number of inhabitants in the age group 50 to 59, AGE50–59 (χ

2 = 8.822,

p-value = 0.003), and terrestrial resources for fighting forest fires, TERRES (χ

2 = 7.542,

p-value = 0.006). The mean values of these last two variables were higher in GROUP 1 than in GROUP 2.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Forest fires are becoming more dangerous worldwide in a combined context of climate and land use changes, which require a new approach to fire risk management [

9,

67,

68]. This study has identified a fairly strong difference between the groups of municipalities that have SCHOOL and those that do not have SCHOOL in relation to the number of forest fires and their distribution over the province of Avila during the period between 1996 and 2023. This result seems logical considering that forest tree coverage is 50% higher in municipalities belonging to GROUP 1 (with SCHOOL), and also the number of inhabitants and their population density. It is also consistent with previous studies that suggest that fire risk increases with the presence of people, rather than their density [

69]. On average, the villages with a SCHOOL have 3.3 times more inhabitants than those without rural elementary schools. As they are larger villages, they also have a better infrastructure network. It has been accepted that the presence of a road may degrade ecosystems [

54,

70] and increases fire ignition risk, particularly in the Mediterranean region [

71,

72]. Nothing new so far. However, our main finding is that the mean value of forest area burned (FIREA) was higher in municipalities without a SCHOOL, despite them showing a statistically significant lower average number of CONATUS.

This is a very interesting finding because Colonico et al. [

9] suggested a relevant role of managed rural areas in mitigating fires in Italy. However, they also found a spatial mismatch between direct prevention expenditures and high-fire activity contexts. This was unlike our case, because terrestrial resources for fighting forest fires (TERRES) are mostly located in municipalities with SCHOOL, which also proved to have, on average, a larger forest area. Even though there are more CONATUS in these municipalities, it is also logical to think that a faster response and the mobilization of TERRES make it possible to fight forest fires more effectively [

17], resulting in less burned area on average. This is despite the greater orographic variations in SLOPE and ALTITU that resulted in the municipalities with SCHOOL and its statistically significant effect according to the GLM analysis.

The importance of infrastructure in maintaining rural populations has been demonstrated [

73], but the role of schools in determining their contribution as a cause or consequence of rural depopulation does not seem entirely clear. Previous research has not found the school to be a key factor in maintaining population, although it places an important symbolic value on its permanence or closure [

47,

74,

75]. Some authors point out that a solid labour base and affordable housing are more important factors in maintaining rural activities than the presence or absence of an elementary school [

43]. However, it seems multifactorial and probably the lack of services, together with poor transportation connections and limited employment and leisure options, are causing young people to leave these areas. In our case study, the mean age (MEAGE) of the municipalities with SCHOOL is 5 years lower, and the GLM showed a statistically significant effect of AGE50–59. Although there are more inhabitants in this age group in municipalities with SCHOOL, we observed a faster increase in depopulation processes (DIFDENS) in these municipalities. This is a reflection of the fact that the population is not fixed, even when they almost double the number of agricultural and livestock holdings. Therefore, the lack of generational replacement leads to the current transformation of landscapes and increased forest fire risk [

24].

There is a positive correlation between the number of inhabitants and the existence of primary schools, as well as other public services and infrastructures (e.g., TERRES and ROADENS). It is also evidence that rural depopulation means school closures [

38]. One direct consequence of the decline in rural populations is the cessation of agricultural, livestock, and forestry practices and activities associated with traditional land management. From a forestry perspective, an assessment of their potential environmental impact is essential [

26], with particular consideration given to the potential for increased risk of forest fires [

4]. Regarding these matters, in many countries there exists a growing controversy about the criteria for closing rural schools [

45,

76]. A local school is not the only thing that makes communities livable [

38], but small rural schools have been found to promote social cohesion and social capital, and to contribute to the general “health of a community” [

45]. Even more, Oncescu and Giles [

46] demonstrated the profound effects that the closure of a rural school can have, not only in diminishing the population’s sense of community, but also in fear for the community’s future, even among residents without school-age children.

The inability to maintain economic activities in sparsely populated areas also causes higher aging rates whose environmental impact has been remarkable through the increasing number of fires in the North-Western region of Spain [

30]. Many authorities in Southern Europe have turned rural areas into consumption spaces, seeking to correspond to a demand for leisure and tourism from urban populations trying to fight depopulation [

77]. Nevertheless, this is not enough to keep the type of land management required to mitigate forest fire risk at a landscape scale [

9]. Integrating indirect prevention measures within fire management plans could be a cost-effective approach to leverage the impact of public policies on forest fire risk management [

9]. One critical need for fire management is the co-management of forest fires to “scale up” fire mitigation efforts to the landscape level by bringing and engaging together diverse stakeholders (i.e., administrations, landowners, and interest groups) to promote coordinated actions that help change current risk trends and unwanted outcomes [

78].

In a context of population decline of rural areas, retaining small schools may contribute to maintaining rural community vibrancy [

41,

76]. It is crucial that policymakers consider the potential link between the decline of essential services in rural areas and the rising risk of forest fires, which could threaten nature conservation [

71], from a holistic point of view [

32,

36]. In this sense, our work has highlighted the potential role of rural primary schools among the set of socioeconomic factors that higher-level policies should take into account when managing the territory to try to reduce the negative effects of natural disasters such as forest fires. Maintaining and promoting primary schools is beyond the scope of forest managers and environmental policymakers, but together with other basic services and infrastructure, can contribute to counteracting rural depopulation and safeguarding the environment. Moreover, it should not be overlooked that rurality can also be considered, in the context of human rights and social justice, as a type of diversity to be supported [

41].

In relation to further research possibilities, it is worth mentioning that, for example, Ager et al. [

79] found a variable influence of roads on the risk of fires in France throughout the summer season. One aspect of interest is trying to understand how the existence of SCHOOL can reflect the way in which dwellers of a municipality behave in terms of activities and land uses associated with their demographic profile [

37]. New insights on this matter would require accessible data sources that include information on the exact dates of occurrence of each fire and additional details on the rest of the socioeconomic variables adjusted to the seasonal scale. Another aspect to be taken into account in future research is the potential effect of climate change. Climate change is a challenge because it may influence risk factors for forest fires [

80], but also it can affect educational [

81], agricultural and livestock policies [

82], and rural depopulation processes [

83].

This research offers a new outlook into the study of relationships between socioeconomic factors and forest fire science. Previous research relating forest fires and rural schools did so from approaches far removed from our work. For example, some researchers evaluated the importance given by elementary school teachers to forest fires or to educating the community about natural disasters and their perception of risk [

84,

85]. Otherwise, Espinoza et al. [

86] highlighted the importance of the school as a focus of attraction for the return of many families in areas affected by natural disasters such as earthquakes, tsunamis, floods, forest fires, and volcanic eruptions that regularly affect a territory. Likewise, O’Donnell [

87] noted that firefighters have home and school facilities for their families in small settlements established in the forest in Western Australia. Finally, a third line of work had to do with the effects of fires as a major source of air pollution in human health and its impact on educational development among different social groups or expenditures on school supplies [

88,

89].

In conclusion, our results, referring to Ávila, a province in central Spain affected by rural depopulation and a remarkable forest fire activity year after year, show statistically significant linkages between indicators of socioeconomic, environmental (i.e., fighting forest fires), and educational policies in rural territories. Therefore, decisions on the presence and distribution of rural primary schools can have an impact on the potential negative effects of forest fires in a territory and, ultimately, with consequences on our environment. Our work is not about specificities such as fire regime or ignition density analysis of forest fires in the terrain, but, from a land governance and planning point of view, it reinforces the need for greater coordination between different policies with a holistic vision and integration of criteria and resources.