Responses of Tree Growth and Intrinsic Water Use Efficiency to Climate Factors and Human Activities in Upper Reaches of Tarim River in Alaer, Xinjiang, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Sampling Location

2.2. Tree Ring Analysis

2.3. The δ13C and δ18O Analyses

2.4. Calculation of Physiological Parameters

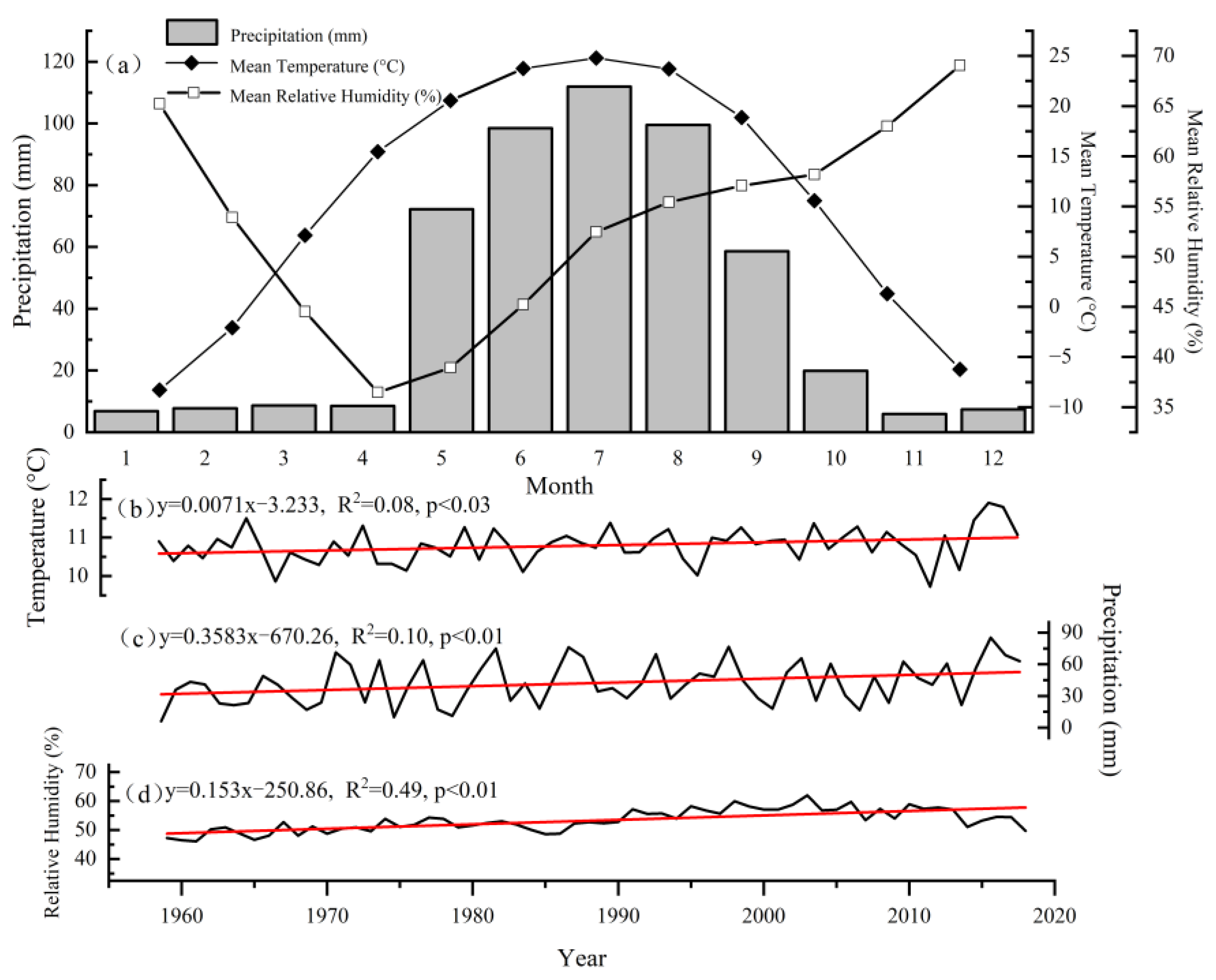

2.5. Climate Data

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Trends of Tree-Ring Width, Tree-Ring Width Index, and BAI

3.2. Long-Term Changes in Δ13C and δ18O, and iWUE and δ18O

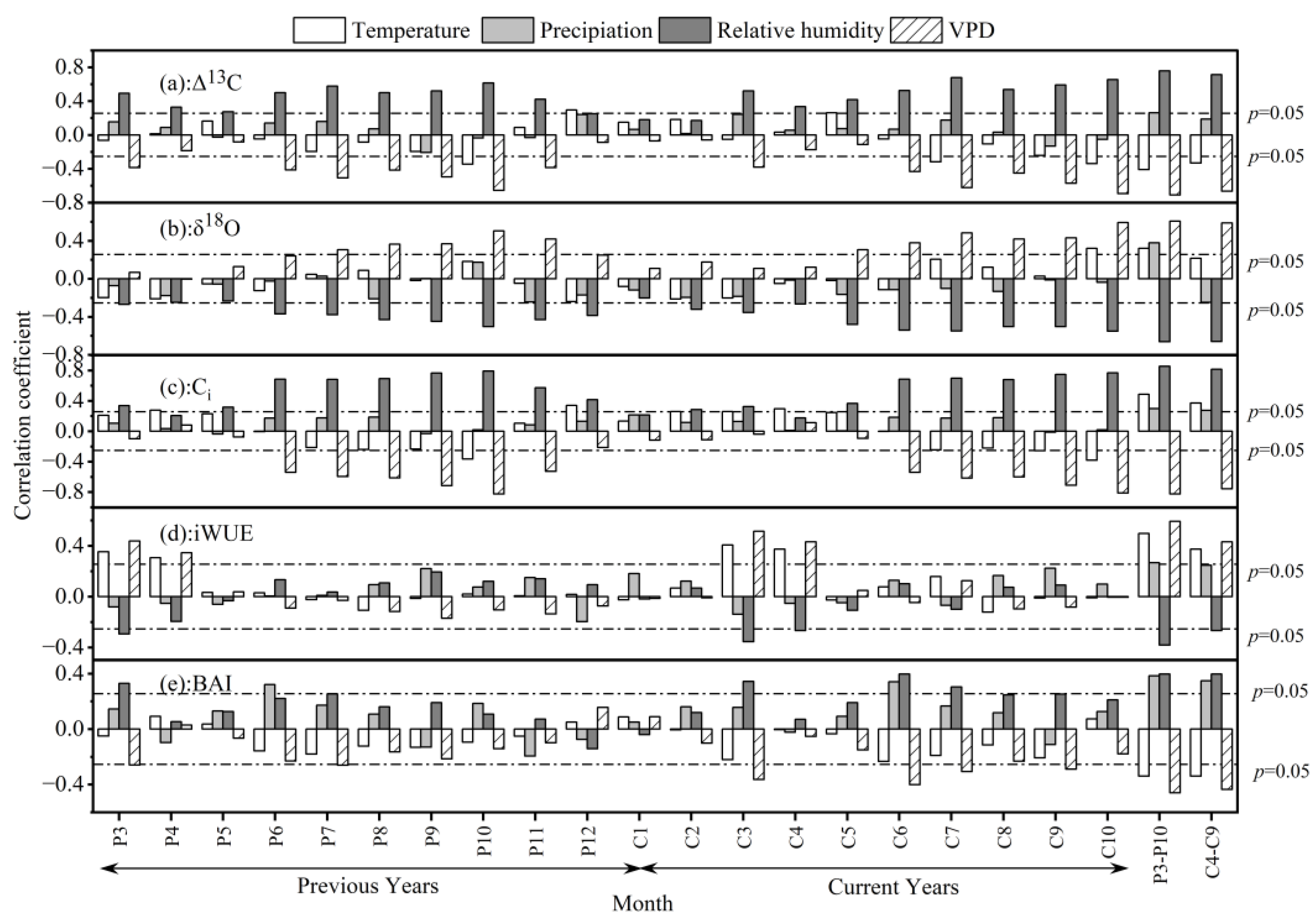

3.3. Climate Response of Δ13C, δ18O, Ci, BAI, and iWUE

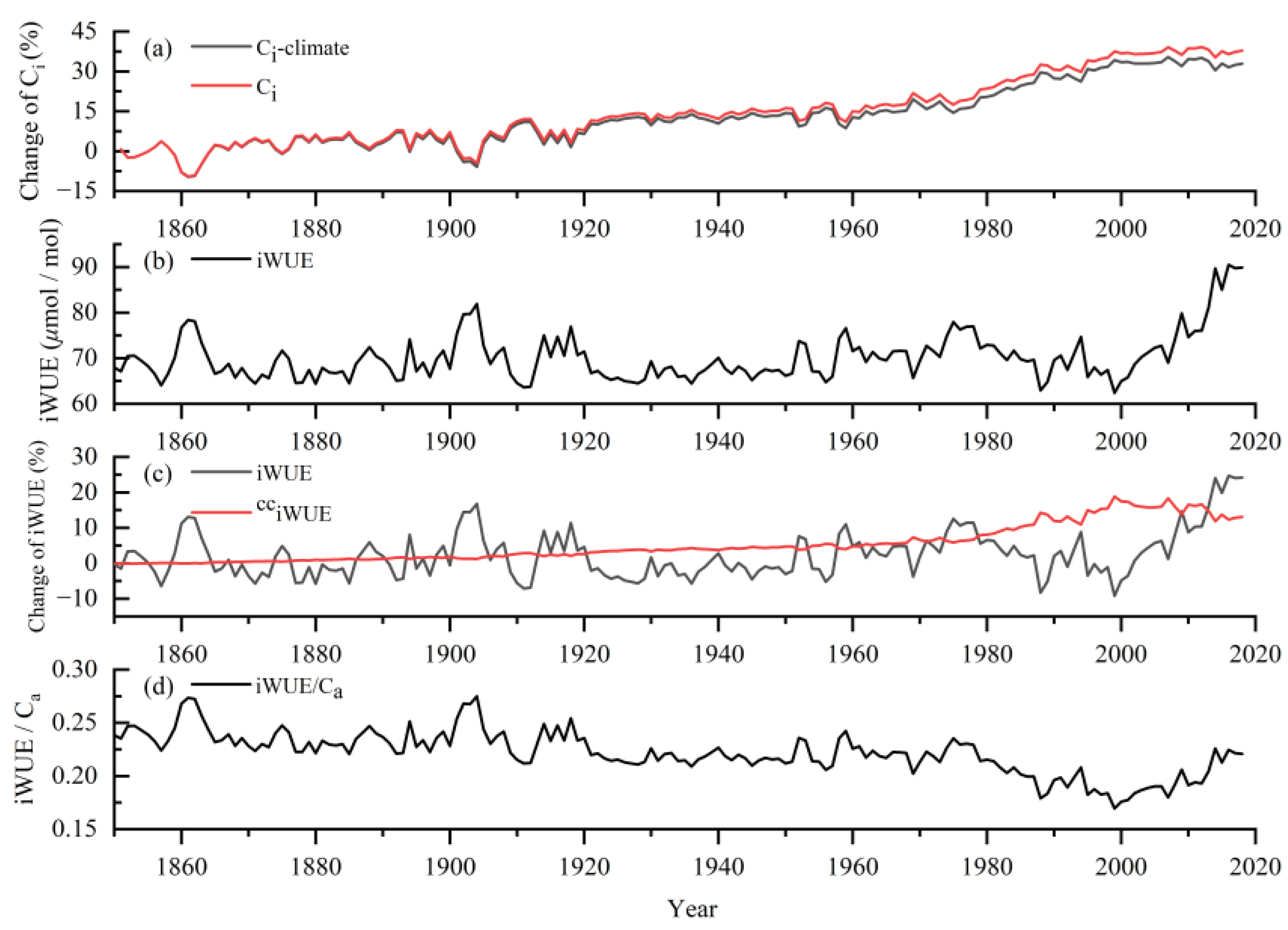

3.4. Long-Term Changes of Ci and iWUE

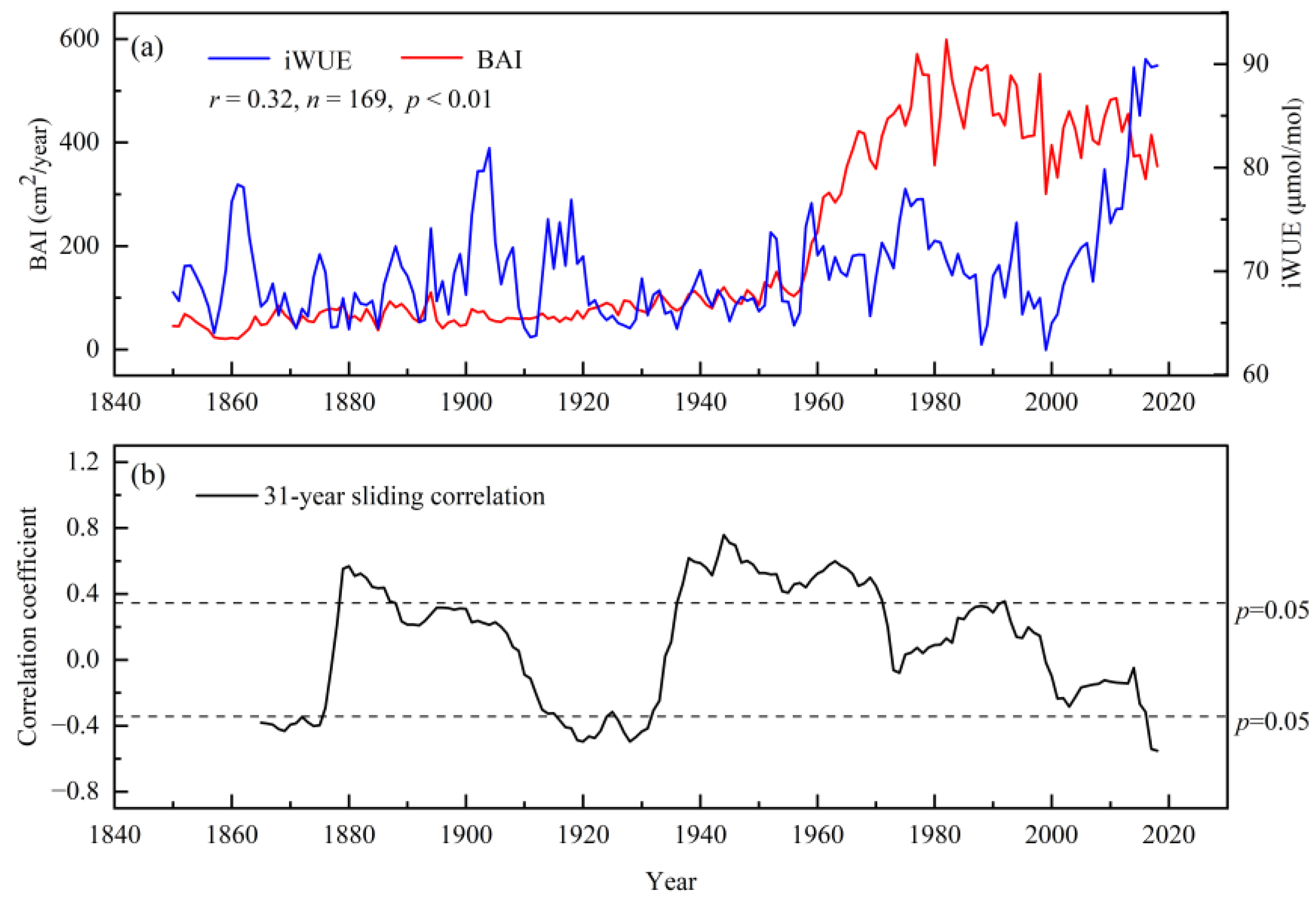

3.5. Relationship between BAI and iWUE of Populus Euphratica

4. Discussion

4.1. The Impact of Climate and Human Activities on the Growth Process

4.2. Analysis of the Reasons for Changes in Intrinsic Water Use Efficiency of Populus Euphratica and Its Relationship with BAI

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderegg, W.R.; Schwalm, C.; Biondi, F.; Camarero, J.J.; Koch, G.; Litvak, M.; Ogle, K.; Shaw, J.D.; Shevliakova, E.; Williams, A. Pervasive drought legacies in forest ecosystems and their implications for carbon cycle models. Science 2015, 349, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalhais, N.; Forkel, M.; Khomik, M.; Bellarby, J.; Jung, M.; Migliavacca, M.; Saatchi, S.; Santoro, M.; Thurner, M.; Weber, U. Global covariation of carbon turnover times with climate in terrestrial ecosystems. Nature 2014, 514, 213–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, Y.; Xia, N.; Terrer, C.; Guo, H.; Du, E. Urban CO2 imprints on carbon isotope and growth of Chinese pine in the Beijing metropolitan region. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 866, 161389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu-Hayles, L.; Planells, O.; Gutierrez, E.; Muntan, E.; Helle, G.; Anchukaitis, K.J.; Schleser, G.H. Long tree-ring chronologies reveal 20th century increases in water-use efficiency but no enhancement of tree growth at five Iberian pine forests. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2011, 17, 2095–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarroll, D.; Gagen, M.H.; Loader, N.J.; Robertson, I.; Anchukaitis, K.J.; Los, S.; Young, G.H.F.; Jalkanen, R.; Kirchhefer, A.; Waterhouse, J.S. Correction of tree ring stable carbon isotope chronologies for changes in the carbon dioxide content of the atmosphere. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2009, 73, 1539–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Song, H.; An, Z.; Sun, C.; Zeng, X. Recent anthropogenic curtailing of Yellow River runoff and sediment load is unprecedented over the past 500 y. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 201922349. [Google Scholar]

- Fritts, H. Tree Rings and Climate; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; p. 567. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, P.; Xu, H.; Ye, M.; Liu, S.; Gong, J.; An, H.; Fu, J. Effects of ecological water conveyance on the ring increments of Populus euphratica in the lower reaches of Tarim River. J. For. Res. 2012, 17, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquhar, G.; O’Leary, M.; Berry, J. On the relationship between carbon isotope discrimination and the intercellular carbon dioxide concentration in Leaves. Funct. Plant Biol. 1982, 9, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarroll, D.; Loader, N.J. Stable isotopes in tree rings. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2004, 23, 771–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheidegger, Y.; Saurer, M.; Bahn, M.; Siegwolf, R. Linking stable oxygen and carbon isotopes with stomatal conductance and photosynthetic capacity: A conceptual model. Oecologia 2000, 125, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castruita-Esparza, L.U.; Silva, L.C.R.; Gomez-Guerrero, A.; Villanueva-Diaz, J.; Correa-Diaz, A.; Horwath, W.R. Coping with extreme events: Growth and Water-Use Efficiency of trees in Western Mexico during the driest and wettest periods of the past one hundred sixty years. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2019, 124, 3419–3431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, J.M.; Thomas, R.B. Global tree intrinsic water use efficiency is enhanced by increased atmospheric CO2 and modulated by climate and plant functional types. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2014286118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, W.W.; Yu, X.X.; Jia, G.D.; Li, H.Z.; Liu, Z.Q. Responses of intrinsic water-use efficiency and tree growth to climate change in semi-arid areas of North China. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 308. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Guo, M.; Lu, Q.; Xu, K.; Shao, H.; Mo, Q.; Liu, S. Spatial and temporal patterns of the sensitivity of radial growth response by Picea schrenkiana to regional climate change in the Tianshan Mountains. J. For. Res. 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, O.Y.; Shao, X.M. Long-term changes in the tree radial growth and intrinsic water-use efficiency of Chuanxi spruce (Picea likiangensis var. balfouriana) in southwestern China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 833–844. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.; Zhu, H.; Liu, X.; Liang, E.; Grießinger, J.; Wu, G.; Li, X.; Bräuning, A. Does increasing intrinsic water use efficiency (iWUE) stimulate tree growth at natural alpine timberline on the southeastern Tibetan Plateau? Glob. Planet. Chang. 2017, 148, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, G.D.; Chen, L.X.; Yu, X.X.; Liu, Z.Q. Soil water stress overrides the benefit of water-use efficiency from rising CO2 and temperature in a cold semi-arid poplar plantation. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 1172–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.C.; Zhang, Y.D.; Li, Z.S.; Han, S.J.; Wang, X.C. Climate change increased the intrinsic water use efficiency of Larix gmelinii in permafrost degradation areas, but did not promote its growth. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 320, 108957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaMarche, V.C.; Graybill, D.A.; Fritts, H.C.; Rose, M.R. Increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide: Tree ring evidence for growth enhancement in natural vegetation. Science 1984, 225, 1019–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schook, D.M.; Friedman, J.M.; Stricker, C.A.; Csank, A.Z.; Cooper, D.J. Short- and long-term responses of riparian cottonwoods (Populus spp.) to flow diversion: Analysis of tree -ring radial growth and stable carbon isotopes. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 735, 139523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannenberg, S.A.; Driscoll, A.W.; Szejner, P.; Anderegg, W.R.L.; Ehleringer, J.R. Rapid increases in shrubland and forest intrinsic water-use efficiency during an ongoing megadrought. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2118052118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, T.T.; Zhai, Y.N.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, W.J.; Dong, J.B.; Liu, X.; Fan, P.X.; You, C.; Yu, L.Q.; Gao, Q.; et al. Impacts of climate change and human activities on vegetation coverage variation in mountainous and hilly areas in Central South of Shandong Province based on tree-ring. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1158221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albiero, A.; Camargo, J.L.C.; Roig, F.A.; Schongart, J.; Pinto, R.M.; Venegas-Gonzalez, A.; Tomazello-Filho, M. Amazonian trees show increased edge effects due to Atlantic Ocean warming and northward displacement of the Intertropical Convergence Zone since 1980. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 693, 133515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dangerfield, C.R.; Voelker, S.L.; Lee, C.A. Long-term impacts of road disturbance on old-growth coast redwood forests. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 499, 119595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensula, B.M. δ13C and Water Use Efficiency in the Glucose of annual pine tree rings as ecological indicators of the forests in the most industrialized part of Poland. Water Air Soil Poll. 2016, 227, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrieri, R.; Vanguelova, E.; Pitman, R.; Benham, S.; Perks, M.; Morison, J.I.L.; Mencuccini, M. Climate and atmospheric deposition effects on forest water-use efficiency and nitrogen availability across Britain. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.F.; Duan, H.L.; Shen, F.F.; Liao, Y.C.; Li, Q.; Wu, J.P. Effects of long-term nitrogen addition on water use by Cunninghamia lanceolate in a subtropical plantation. Ecosphere 2022, 13, e4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sensula, B.M. Spatial and Short-Temporal variability of δ13C and δ15N and water-use efficiency in pine needles of the three forests along the most industrialized part of Poland. Water Air Soil Poll. 2015, 226, 362.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, K.; Cherubini, P.; Bugmann, H.; Schleppi, P. Growth enhancement of Picea abies trees under long-term, low-dose N addition is due to morphological more than to physiological changes. Tree Physiol. 2012, 32, 1471–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachar, A.; Markus-Shi, J.; Regev, L.; Boaretto, E.; Klein, T. Tree rings reveal the adverse effect of water pumping on protected riparian Platanus orientalis tree growth. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 458, 117784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matulewski, P.; Buchwal, A.; Makohonienko, M. Higher climatic sensitivity of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) subjected to tourist pressure on a hiking trail in the Brodnica Lakeland, NE Poland. Dendrochronologia 2019, 54, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.H.; Zhao, C.Y.; Wu, G.L.; Jiang, S.W.; Yu, Y.X.; Wang, D.D. Application of stable isotopes in analyzing the water sources of Populus euphratica and Tamarix ramosissima in the upstream of Tarim River. J. Desert Res. 2017, 37, 124–131. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, H.H.; Chen, Y.N.; Zhu, C.G.; Li, Z.; Fang, G.H.; Li, Y.P.; Fu, A.H. Climate change may accelerate the decline of desert riparian forest in the lower Tarim River, Northwestern China: Evidence from tree-rings of Populus euphratica. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 111, 105997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, P.; Ahlborn, J.; Schaefer, P.; Wommelsdorf, T.; Jeschke, M.; Zhang, X.M.; Thomas, F.M. Growth and water use of Populus euphratica trees and stands with different water supply along the Tarim River, N.W. China. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 380, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, H.; Guo, B.; Zhang, G.; Xu, H.; Deng, X. Evaluation of the ecological protective effect of the "large basin" comprehensive management system in the Tarim River basin, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 650, 1696–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.Y.; Xu, H.L.; Ye, M.; Li, B.L.; Fu, J.Y.; Yang, Z.F. Impact of long-term zero-flow and ecological water conveyance on the radial increment of Populus euphratica in the lower reaches of the Tarim River, Xinjiang, China. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2015, 15, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H.; Wang, W.Z.; Xu, G.B.; Zeng, X.M.; Wu, G.J.; Zhang, X.W.; Qin, D.H. Tree growth and intrinsic water-use efficiency of inland riparian forests in northwestern China: Evaluation via delta C-13 and delta O-18 analysis of tree rings. Tree Physiol. 2014, 34, 966–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Fourteenth Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps History Compilation Committee Division. The Local Chronicles of the Fourteenth Division of Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps; Xinjiang People’s Publishing House: Urumqi, China, 2000; p. 20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, R.L. Computer-assisted quality control in tree-ring dating and measurement. Tree-Ring Bull. 1983, 43, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bunn, A.G. A dendrochronology program library in R (dplR). Dendrochronologia 2008, 26, 115–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, F.; Qeadan, F. A theory-driven approach to tree-ring standardization: Defining the biological trend from expected basal area increment. Tree-Ring Res. 2008, 64, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ren, M.; Li, Q.; Song, H.; Liu, R. Tree-ring δ18O based July-August relative humidity reconstruction on Mt. Shimen, China, for the last 400 years. Atmos. Res. 2020, 243, 105024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Q.; Cai, Q.F.; Song, H.M.; Sun, C.F.; Liu, R.S.; Mei, R.C. Asian summer monsoon-related relative humidity recorded by tree ring δ18O during last 205 Years. J. Geophys. Res. -Atmos. 2019, 124, 9824–9838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coplen, T.B.; Brand, W.A.; Gehre, M.; Gröning, M.; Meijer, H.A.; Toman, B.; Verkouteren, R.M. New guidelines for δ13C measurements. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 2439–2441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saugier, B.; Ehleringer, J.R.; Hall, A.E.; Farquhar, G.D. Stable isotopes and plant carbon-water relations; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993; p. 463. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, D.C.; Poulter, B.; Saurer, M.; Esper, J.; Huntingford, C.; Helle, G.; Treydte, K.; Zimmermann, N.E.; Schleser, G.H.; Ahlstrom, A.; et al. Water-use efficiency and transpiration across European forests during the Anthropocene. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2015, 5, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachauri, R.K.; Allen, M.R.; Barros, V.R.; Broome, J.; Cramer, W.; Christ, R.; Church, J.A.; Clarke, L.; Dahe, Q.; Dasgupta, P.; et al. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014; p. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Saurer, M.; Siegwolf, R.T.W.; Schweingruber, F.H. Carbon isotope discrimination indicates improving water-use efficiency of trees in northern Eurasia over the last 100 years. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2004, 10, 2109–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.A.; Buckley, T.N.; Turnbull, T.L. Diminishing CO2-driven gains in water-use efficiency of global forests. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.Y. Water Use Strategies and Adaptation to Drought Stress in Populus euphratica of Riparian Desert Forest. Doctor’s Thesis, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington, A.M.; Woodward, F.I. The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature 2003, 424, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossiord, C.; Buckley, T.N.; Cernusak, L.A.; Novick, K.A.; Poulter, B.; Siegwolf, R.T.; Sperry, J.S.; McDowell, N.G. Plant responses to rising vapour pressure deficit. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 1550–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H.; Xu, G.B.; Wang, W.Z.; Wu, G.J.; Zeng, X.M.; An, W.L.; Zhang, X.W. Tree-ring stable isotopes proxies: Progress, problems and prospects. Quat. Sci. 2015, 35, 1245–1260. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, C.X. Channel change of Tarim River and its response to human activities from the 18th century. J. Desert Res. 2011, 31, 1072–1078. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, G.A.; Li, Z.W.; Huang, H.Q.; Liu, X.F. Human impacts on fluvial processes in a very arid environment: The case of Tarim River in China. Adv. Water Sci. 2017, 28, 183–192. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Nian, F.H. Effect of human activities on groundwater in Alaer irrigation area in Xinjiang. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 1999, 13, 41–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yong, Z.; Zhao, C.Y.; Shi, F.Z.; Ma, X.F. Variation characteristics of groundwater depth and its ecological effect in the mainstream of Tarim River in recent 20 years. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2020, 34, 182–189. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.M.; Xiao, S.C.; Cheng, G.D.; Xiao, H.L.; Tian, Q.Y.; Zhang, Q.B. Human activity impacts on the stem radial growth of Populus euphratica riparian forests in China’s Ejina Oasis, using tree-ring analysis. Trees-Struct. Funct. 2017, 31, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, J.; Feng, Q.; Cao, S.; Yu, T.; Zhao, C. Water use sources of desert riparian Populus euphratica forests. Env. Monit Assess 2014, 186, 5469–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.X.; Xiao, H.L.; Luo, F.; Li, S.Z.; Song, Y.X.; Xiao, C.S. Groundwater salinity characters and their relationship with vegetation growth in Ejin delta. J. Desert Res. 2004, 24, 6. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.F. The yearly ring and water-heat index in the middle reach of the Tarim River. Arid Land Geogr. 1988, 11, 17–23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.F.; Yuan, Y.J.; You, X.Y. Research and Application of Tree Ring Hydrology; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2000; pp. 22–23. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, D.; Li, W.H.; Chen, Y.P.; Liu, J.Z. Relations between groundwater and natural vegetation in the arid zone. Resour. Sci. 2005, 27, 160–167. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. Study on the relationship between vegetation and brackish water distribution in Alar Oasis. Master’s Thesis, Shihezi University, Shihezi, China, 2019. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Huo, A.; Wang, X.; Guan, W.; Zhong, J.; Yi, X.; Wen, Y. Soil physico-chemical properties and their effects on Populus euphratica growth in desertification areas. Ukr. J. Ecol. 2019, 9, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, P.J.; Adams, M.A.; Amthor, J.S.; Barbour, M.M.; Berry, J.A. Sensitivity of plants to changing atmospheric CO2 concentration: From the geological past to the next century. New Phytol. 2013, 197, 1077–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Islam, M.; Gebrekirstos, A.; Bräuning, A. Disentangling the effects of atmospheric CO2 and climate on intrinsic water-use efficiency in South Asian tropical moist forest trees. Tree Physiol. 2020, 40, 904–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xu, C.; Li, W. Groundwater depth affects the daily course of gas exchange parameters of Populus euphratica in arid areas. Environ. Earth Sci. 2012, 66, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Ficklin, D.L.; Manzoni, S.; Wang, L.; Way, D.; Phillips, R.P.; Novick, K.A. Response of ecosystem intrinsic water use efficiency and gross primary productivity to rising vapour pressure deficit. Environ. Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 074023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Zheng, Y.; Piao, S.; Ciais, P.; Lombardozzi, D.; Wang, Y.; Ryu, Y.; Chen, G.; Dong, W.; Hu, Z. Increased atmospheric vapour pressure deficit reduces global vegetation growth. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Li, G.F.; He, Y.L.; Mu, Y.D.; Zhuang, L.; Liu, H.L. Water utilization sources of Populus euphratica trees of different ages in the lower reaches of Tarim River. Biodivers. Sci. 2018, 26, 564–571. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shi, Y.F.; Shen, Y.P.; Li, D.L.; Zhang, G.W.; Ding, Y.J.; Hu, R.J.; Kang, E.S. Discussion on the present climate change from Warm-dry to Warm-wet in Northwest China. Quat. Sci. 2003, 23, 152–164. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.P.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, C.Y.; Li, W.J. Characteristics of the foliar stable carbon isotope composition of Populus euphratica for different Niche in the Lower Reach of the Heihe River. J. Desert Res. 2015, 35, 1505–1511. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Silva, L.C.R.; Anand, M. Probing for the influence of atmospheric CO2 and climate change on forest ecosystems across biomes probing for the influence of atmospheric CO2 and climate change on forest ecosystems across biomes. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2013, 22, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ye, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ren, M.; Cai, Q.; Sun, C.; Li, Q.; Song, H.; Ye, M.; Zhang, T. Responses of Tree Growth and Intrinsic Water Use Efficiency to Climate Factors and Human Activities in Upper Reaches of Tarim River in Alaer, Xinjiang, China. Forests 2023, 14, 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14091873

Ye Y, Liu Y, Ren M, Cai Q, Sun C, Li Q, Song H, Ye M, Zhang T. Responses of Tree Growth and Intrinsic Water Use Efficiency to Climate Factors and Human Activities in Upper Reaches of Tarim River in Alaer, Xinjiang, China. Forests. 2023; 14(9):1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14091873

Chicago/Turabian StyleYe, Yuanda, Yu Liu, Meng Ren, Qiufang Cai, Changfeng Sun, Qiang Li, Huiming Song, Mao Ye, and Tongwen Zhang. 2023. "Responses of Tree Growth and Intrinsic Water Use Efficiency to Climate Factors and Human Activities in Upper Reaches of Tarim River in Alaer, Xinjiang, China" Forests 14, no. 9: 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14091873

APA StyleYe, Y., Liu, Y., Ren, M., Cai, Q., Sun, C., Li, Q., Song, H., Ye, M., & Zhang, T. (2023). Responses of Tree Growth and Intrinsic Water Use Efficiency to Climate Factors and Human Activities in Upper Reaches of Tarim River in Alaer, Xinjiang, China. Forests, 14(9), 1873. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14091873