An Example of the Conservation of Wood Decay Fungi: The New Research Culture Collection of Corticioid and Polyporoid Strains of the University of Salamanca (Spain)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Basidiomata Sampling

2.2. Strain Isolation in Pure Culture

2.3. Fungal Strain Morphological and Molecular Identification

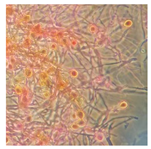

2.4. Growth Tests and Description of the Fungal Strains

3. Results and Discussion

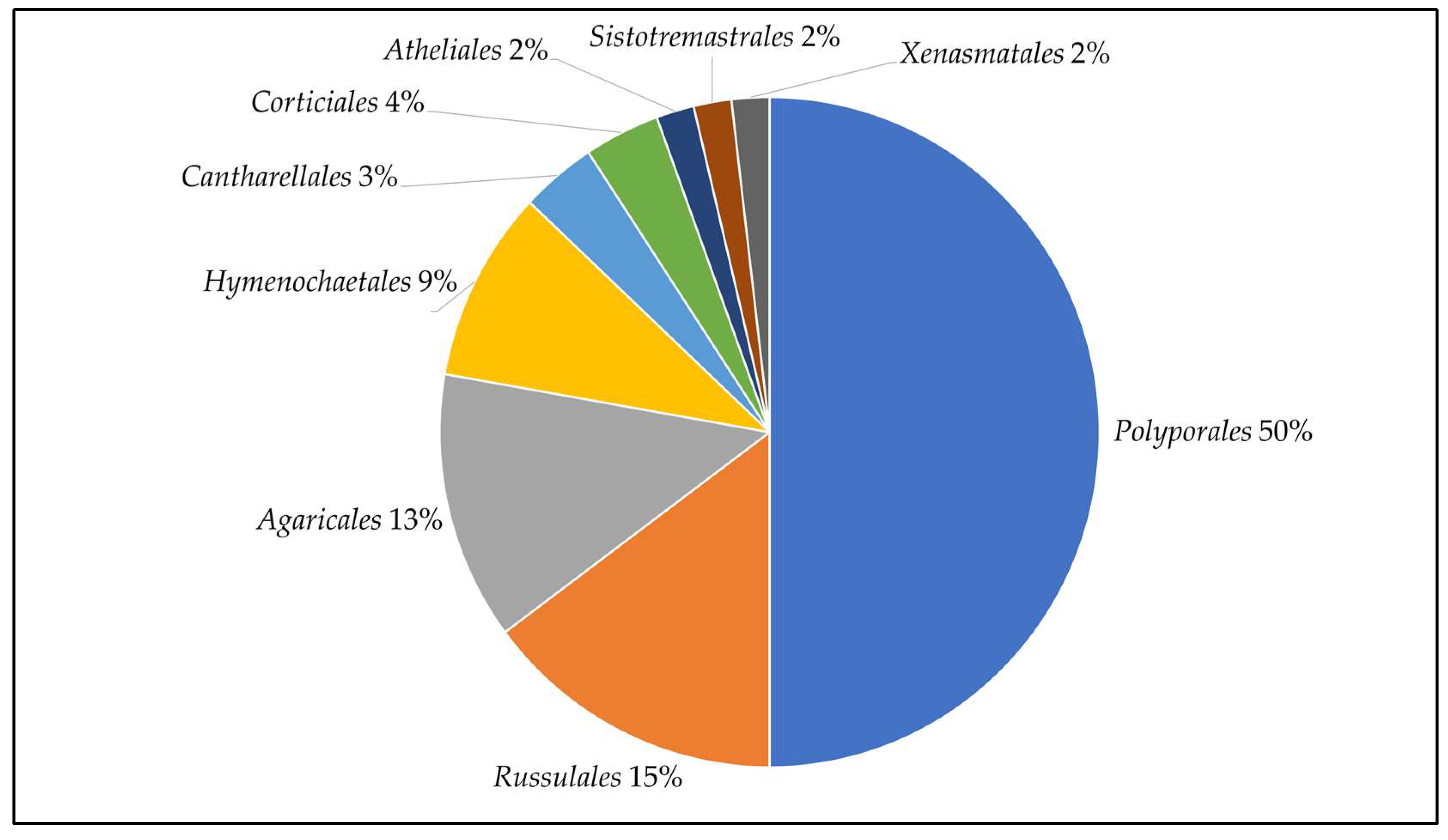

3.1. Basidiomata Sampling, Strains Isolation and Identification

3.2. Description and Growth Rate of Isolated Strains

- -

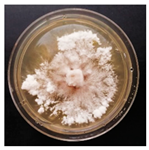

- The mycelium of Phlebiopsis crassa turned purple after a few weeks of growing in isolation, which is also a basidiomata feature. This characteristic was lost in subsequent cultures;

- -

- Hericium erinaceus exhibited two distinct morphologies: one that was more compact and consistently growing (as indicated in Table 3) and one with hyphae bundled to form aerial mycelium;

- -

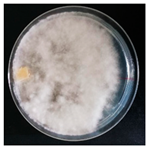

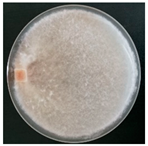

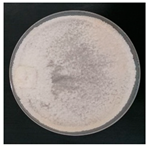

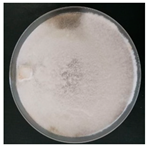

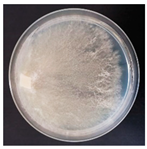

- Truncospora atlantica colonies are characterized by powdery mycelium that can either cover the entire colony, making it entirely white, or cover it partially, resulting in a darker-coloured zonation.

3.3. Notable Species in the New Strain Collection of Salamanca University: Issues and Potentiality

3.3.1. Species of Special Concern for Taxonomical and/or Biogeography Studies

3.3.2. Species of Special Concern for Nutraceutical/Medicinal Properties

3.3.3. Species of Special Concern for Enzymatic and/or Degradation Potential

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 4 October 2023).

- Hawksworth, D.L.; Lücking, R. Fungal diversity revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 million species. Microbiol. Spectr. 2017, 5, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahlberg, A.; Mueller, G.M. Applying IUCN red-listing criteria for assessing and reporting on the conservation status of fungal species. Fungal Ecol. 2011, 4, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Global Fungal Red List Initiative. Available online: https://redlist.info/en/iucn/welcome (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Mueller, G.M.; Cunha, K.M.; May, T.W.; Allen, J.L.; Westrip, J.R.S.; Canteiro, C.; Costa-Rezende, D.H.; Drechsler-Santos, E.R.; Vasco-Palacios, A.M.; Ainsworth, A.M.; et al. What Do the First 597 Global Fungal Red List Assessments Tell Us about the Threat Status of Fungi? Diversity 2022, 14, 736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, C.J.; Asplund, J.; Benesperi, R.; Branquinho, C.; Di Nuzzo, L.; Hurtado, P.; Martínez, I.; Matos, P.; Nascimbene, J.; Pinho, P.; et al. Functional Traits in Lichen Ecology: A Review of Challenge and Opportunity. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dighton, J.; Sridhar, K.R.; Deshmukh, S.K. The Roles of Macro Fungi (Basidomycotina) in Terrestrial Ecosystems. In Advances in Macrofungi: Diversity, Ecology and Biotechnology; CRC-Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; pp. 70–104. [Google Scholar]

- Heilmann-Clausen, J.; Barron, E.S.; Boddy, L.; Dahlberg, A.; Griffith, G.W.; Nordén, J.; Ovaskainen, O.; Perini, C.; Senn-Irlet, B.; Halme, P. A fungal perspective on conservation biology. Conserv. Biol. 2015, 29, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, M.N.; Berrin, J.G.; Lomascolo, A. Plant Wastes and Sustainable Refineries: What Can We Learn from Fungi? Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 34, 100602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selbmann, L.; Egidi, E.; Isola, D.; Onofri, S.; Zucconi, L.; de Hoog, G.S.; Chinaglia, S.; Testa, L.; Tosi, S.; Balestrazzi, A.; et al. Biodiversity, Evolution and Adaptation of Fungi in Extreme Environments. Plant Biosyst.—Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2013, 147, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, L.G.; Riley, R.; Bergmann, P.J.; Krizsán, K.; Martin, F.M.; Grigoriev, I.V.; Cullen, D.; Hibbett, D.S. Genetic Bases of Fungal White Rot Wood Decay Predicted by Phylogenomic Analysis of Correlated Gene-Phenotype Evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2017, 34, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krah, F.S.; Bässler, C.; Heibl, C.; Soghigian, J.; Schaefer, H.; Hibbett, D.S. Evolutionary Dynamics of Host Specialization in Wood-Decay Fungi. BMC Evol. Biol. 2018, 18, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, K.D.; Xu, J.; Rapior, S.; Jeewon, R.; Lumyong, S.; Niego, A.G.T.; Abeywickrama, P.D.; Aluthmuhandiram, J.V.S.; Brahamanage, R.S.; Brooks, S.; et al. The amazing potential of fungi: 50 ways we can exploit fungi industrially. Fungal Divers. 2019, 97, 1–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerimi, K.; Akkaya, K.C.; Pohl, C.; Schmidt, B.; Neubauer, P. Fungi as Source for New Bio-Based Materials: A Patent Review. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2019, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almpani-Lekka, D.; Pfeiffer, S.; Schmidts, C.; Seo, S. A Review on Architecture with Fungal Biomaterials: The Desired and the Feasible. Fungal Biol. Biotechnol. 2021, 8, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, R.; Fan, F. A Comprehensive Insight into the Application of White Rot Fungi and Their Lignocellulolytic Enzymes in the Removal of Organic Pollutants. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 778, 146132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WFCC—World Federation for Culture Collections. Available online: https://wfcc.info/guideline (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Sette, L.D.; Pagnocca, F.C.; Rodrigues, A. Microbial Culture Collections as Pillars for Promoting Fungal Diversity, Conservation and Exploitation. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2013, 60, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Vero, L.; Boniotti, M.B.; Budroni, M.; Buzzini, P.; Cassanelli, S.; Comunian, R.; Gullo, M.; Logrieco, A.F.; Mannazzu, I.; Musumeci, R.; et al. Preservation, Characterization and Exploitation of Microbial Biodiversity: The Perspective of the Italian Network of Culture Collections. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Federation for Culture Collections: Guidelines for the Establishment and Operation of Collections of Cultures of Microorganisms, 3rd Edition, February 2010. Available online: https://wfcc.info/home_view (accessed on 2 September 2023).

- Santos, I.M.; Lima, N. Criteria Followed in the Establishment of a Filamentous Fungal Culture Collection—Micoteca Da Universidade Do Minho (MUM). World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 17, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Microbial Resource Research Infrastructure (MIRRI). Available online: https://www.mirri.org/ (accessed on 4 October 2023).

- Becker, P.T.; Stubbe, D.; Claessens, J.; Roesems, S.; Bastin, Y.; Planard, C.; Cassagne, C.; Piarroux, R.; Hendrickx, M. Quality control in culture collections: Confirming identity of filamentous fungi by MALDI-TOF MS. Mycoscience 2014, 56, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartabia, M.; Girometta, C.E.; Baiguera, R.M.; Buratti, S.; Babbini, S.; Bernicchia, A.; Savino, E. Lignicolous fungi collected in northern Italy: Identification and morphological description of isolates. Diversity 2022, 14, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girometta, C.E.; Bernicchia, A.; Baiguera, R.M.; Bracco, F.; Buratti, S.; Cartabia, M.; Picco, A.M.; Savino, E. An Italian Research Culture Collection of Wood Decay Fungi. Diversity 2020, 12, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Data. Available online: https://it.climate-data.org/europa/spagna/ (accessed on 13 July 2023).

- Gams, W.; Van der Aa, H.A.; Van der Plaats-Niterink, A.J.; Samson, R.A.; Stalpers, J.A. CBS Course of Mycology (No. Ed. 3). Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS); Westerdjik: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hakala, T.K.; Maijala, P.; Konn, J.; Hatakka, A. Evaluation of novel wood-rotting polypores and corticioid fungi for the decay and biopulping of Norway spruce (Picea abies) wood. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2004, 34, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernicchia, A.; Gorjón, S.P. Polypores of the Mediterranean Region; Romar: Segrate, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, Y.W.; Hyde, K.D.; Ho, W.H. Single spore isolation of fungi. Fungal Divers. 1999, 3, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bernicchia, A.; Gorjón, S.P. Corticiaceae sl.; Fungi Europaei 12; Candusso: Alassio, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, K.H.; Ryvarden, L. Corticioid Fungi of Europe: Acanthobasidium-Gyrodontium; Fungiflora: Oslo, Norway, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- NCBI. Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Mycobank. Available online: www.mycobank.org (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Nobles, M.K. Identification of cultures of wood-inhabiting Hymenomycetes. Can. J. Bot. 1965, 43, 1097–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalpers, J.A. Identification of wood-inhabiting fungi in pure culture. Stud. Mycol. 1978, 16, 1–248. [Google Scholar]

- Cartabia, M.; Girometta, C.E.; Milanese, C.; Baiguera, R.M.; Buratti, S.; Branciforti, D.S.; Vadivel, D.; Girella, A.; Babbini, S.; Savino, E.; et al. Collection and Characterization of Wood Decay Fungal Strains for Developing Pure Mycelium Mats. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petre, C.V.; Tanase, C. Culture characteristics of 20 lignicolous basidiomycetes species that synthesize volatile organic compounds. Analele Stiintifice ale Universitatii" Al. I. Cuza" din Iasi 2013, 59, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Balaeş, T.; Tănase, C. Culture description of some spontaneous lignicolous macromycetes species. J. Plant Dev. 2012, 19, 83–97. [Google Scholar]

- Nakasone, K.K. Cultural and morphological studies of Gloeocystidiellum porosum and Gloeocystidium clavuligerum. Mycotaxon 1982, 14, 316–324. [Google Scholar]

- Nagadesi, P.K.; Arya, A.; Babu, D.N.; Prasad, K.S.M.; Devi, P.P. Identification of volatile organic compound producing Lignicolous fungal cultures from Gujarat, India. World Sci. News 2017, 90, 150–165. [Google Scholar]

- Bakshi, B.K.; Sehgal, H.S.; Singh, B. Cultural diagnosis of Indian Polyporaceae. I. Genus Polyporus. Indian For. Rec. 1969, 2, 205–244. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, C.; Xia, Y.; Zheng, P.; Wang, C. Increasing oxidative stress tolerance and subculturing stability of Cordyceps militaris by overexpression of a glutathione peroxidase gene. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 2009–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, G.; Lopez-Moya, F.; Chuina, E.; Ibañez-Vea, M.; Garde, E.; López-Llorca, L.V.; Pisabarro, A.G.; Ramírez, L. Strain degeneration in Pleurotus ostreatus: A genotype dependent oxidative stress process which triggers oxidative stress, cellular detoxifying and cell wall reshaping genes. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CBS-KNAW Collections—Westerdijk Institute. Available online: https://wi.knaw.nl/Collection (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Mut-Mycotheca Universitatis Taurinensis. Available online: https://www.tucc-database.unito.it/mut (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- BCCM/MUCL Agro-Food & Environmental Fungal Collection. Available online: https://bccm.belspo.be/about-us/bccm-mucl (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- LE-BIN Strains—All-Russian Collection of Microorganisms—VKM. Available online: http://www.vkm.ru/eCatalogue/LE-BIN.htm (accessed on 12 July 2023).

- Langer, G. Die gattung Botryobasidium Donk (Corticiaceae, Basidiomycetes). Bibl. Mycol. 1994, 158, 459. [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo, I.; Olariaga, I. Phanerochaete crassa (Lév.) Burds., nueva cita para la micoflora de la Península Ibérica. Rev. Catalana Micol. 2008, 30, 93–99. [Google Scholar]

- Gorjón, S.P.; Hallenberg, N.; Bernicchia, A. A survey of the corticioid fungi from the Biosphere Reserve of Las Batuecas-Sierra de Francia (Spain). Mycotaxon 2009, 109, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresadola, G. Fungi Polonici a el. Viro B. Eichler lecti. Ann. Mycol. 1903, 1, 65–131. [Google Scholar]

- Snowarski, M. Mushrooms and Fungi of Poland. Polish Red List of Macrofungi. 2006. Available online: http://www.grzyby.pl/czerwonalista-Aphyllophorales.htm (accessed on 20 July 2023).

- Wu, J.Y.; Siu, K.C.; Geng, P. Bioactive Ingredients and Medicinal Values of Grifola frondosa (Maitake). Foods 2021, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Nandi, S.; Banerjee, A.; Sarkar, S.; Chakraborty, N.; Acharya, K. Prospecting medicinal properties of Lion’s mane mushroom. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Wang, S.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Q. Medicinal properties of Hericium erinaceus and its potential to formulate novel mushroom-based pharmaceuticals. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 7661–7670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturella, G.; Ferraro, V.; Cirlincione, F.; Gargano, M.L. Medicinal mushrooms: Bioactive compounds, use, and clinical trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, G.A.; Girometta, C.E.; Cusumano, G.; Pellegrino, R.M.; Silviani, S.; Bistocchi, G.; Arcangeli, A.; Ianni, F.; Blasi, F.; Cossignani, L.; et al. Diversity of Pleurotus spp. (Agaricomycetes) and Their Metabolites of Nutraceutical and Therapeutic Importance. Int. J. Med. Mushrooms 2023, 25, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Y.; Narian, R.; Singh, V.K. Medicinal properties of Pleurotus species (Oyster Mushroom): A Review. World J. Fungal Plant Biol. 2012, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Stastny, J.; Marsik, P.; Tauchen, J.; Bozik, M.; Mascellani, A.; Havlik, J.; Landa, P.; Jablonsky, I.; Treml, J.; Herczogova, P.; et al. Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Five Medicinal Mushrooms of the Genus Pleurotus. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezalel, L.; Hadar, Y.; Cerniglia, C.E. Mineralization of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by the white rot fungus Pleurotus ostreatus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996, 62, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozdnyakova, N.N.; Nikitina, V.E.; Turovskaya, O.V. Bioremediation of oil-polluted soil with an association including the fungus Pleurotus ostreatus and soil microflora. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2008, 44, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, T.; Honda, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Kuwahara, M. Degradation of bisphenol A by the lignin-degrading enzyme, manganese peroxidase, produced by the white-rot basidiomycete, Pleurotus ostreatus. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2000, 64, 1958–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aggelis, G.; Iconomou, D.; Christou, M.; Bokas, D.; Kotzailias, S.; Christou, G.; Tsagou, V.; Papanikolaou, S. Phenolic removal in a model olive oil mill wastewater using Pleurotus ostreatus in bioreactor cultures and biological evaluation of the process. Water Res. 2003, 37, 3897–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, C.; Cajthaml, T.; Svobodova, K.; Susla, M.; Sasek, V. Irpex lacteus, a white-rot fungus with biotechnological potential—review. Folia Microbiol. 2009, 54, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, C.; Erbanova, P.; Cajthaml, T.; Rothschild, N.; Dosoretz, C.; Sasek, V. Irpex lacteus, a white rot fungus applicable to water and soil bioremediation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000, 54, 850–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajthaml, T.; Erbanová, P.; Kollmann, A.; Novotný, Č.; Šašek, V.; Mougin, C. Degradation of PAHs by ligninolytic enzymes of Irpex lacteus. Folia Microbiol. 2008, 53, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Song, H.G. Transformation and mineralization of 2, 4, 6-trinitrotoluene by the white rot fungus Irpex lacteus. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 61, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.; Kim, Y.H.; Lim, J. Purification and characterization of manganese peroxidase of the white-rot fungus Irpex lacteus. J. Microbiol. Seoul 2005, 43, 503. [Google Scholar]

- Svobodová, K.; Majcherczyk, A.; Novotn, C.; Kües, U. Implication of mycelium associated laccase from Irpex lacteus in the decolorization of synthetic dyes. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, J.; Hjortstam, K.; Ryvarden, L. The Corticiaceae of North Europe Vol. 5; Fungiflora: Oslo, Norway, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhan, H.; Xiao, T.; Yu, X.; Zheng, Y. Surfactants Double the Biodegradation Rate of Persistent Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) by a White-Rot Fungus Phanerochaete sordida. Environ. Earth Sci. 2023, 82, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Tanaka, Y.; Ohno, H.; Jia, J.; Mori, T.; Xiao, T.; Yan, B.; Kawagishi, H.; Hirai, H. Biotransformation and Detoxification of the Neonicotinoid Insecticides Nitenpyram and Dinotefuran by Phanerochaete sordida YK-624. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastogi, A.; Tiwari, M.K.; Ghangrekar, M.M. A Review on Environmental Occurrence, Toxicity and Microbial Degradation of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs). J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 300, 113694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goppa, L.; Spano, M.; Baiguera, R.M.; Cartabia, M.; Rossi, P.; Mannina, L.; Savino, E. NMR-Based Characterization of Wood Decay Fungi as Promising Novel Foods: Abortiporus biennis, Fomitopsis iberica and Stereum hirsutum Mycelia as Case Studies. Foods 2023, 12, 2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jović, J.; Buntić, A.; Radovanović, N.; Petrović, B.; Mojović, L. Lignin-degrading abilities of novel autochthonous fungal isolates Trametes hirsuta F13 and Stereum gausapatum F28. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 56, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tišma, M.; Žnidaršič-Plazl, P.; Šelo, G.; Tolj, I.; Šperanda, M.; Bucić-Kojić, A.; Planinić, M. Trametes versicolor in Lignocellulose-Based Bioeconomy: State of the Art, Challenges and Opportunities. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 330, 124997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, A.; Justo, A.; Hibbett, D.S. Species Delimitation in Trametes: A Comparison of ITS, RPB1, RPB2 and TEF1 Gene Phylogenies. Mycologia 2014, 106, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elisashvili, V.; Kachlishvili, E.; Tsiklauri, N.; Metreveli, E.; Khardziani, T.; Agathos, S.N. Lignocellulose-degrading enzyme production by white-rot basidiomycetes isolated from the forests of Georgia. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008, 25, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okino, L.K.; Machado, K.M.G.; Fabris, C.; Bononi, V.L.R. Ligninolytic activity of tropical rainforest basidiomycetes. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2000, 16, 889–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshghi, H.; Alishahi, Z.; Zokaei, M.; Daroodi, A.; Tabasi, E. Decolorization of methylene blue by new fungus: Trichaptum biforme and decolorization of three synthetic dyes by Trametes hirsuta and Trametes gibbosa. Eur. J. Chem. 2011, 2, 463–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, M.; Morrell, J.J. Decolorization of the polymeric dye Poly R-478 by wood-inhabiting fungi. Can. J. Microbiol. 1992, 38, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Macroscopical Characters | |||

| Code | Description | Code | Description |

| 1 | Colony colour white, pale or transparent | 11 | Aerial mycelium felty: with mycelium cottony or wooly woven to form a compact surface |

| 2 | Colony colour yellow, ochraceous, brown or others (even if partially) | 12 | Aerial mycelium floccose: with little tufts of hyphae |

| 3 | Reverse of Petri dish colour unchanged | 13 | Colony lacunose: with depressions on the surface |

| 4 | Reverse of Petri dish colour bleached | 14 | Aerial mycelium plumose: with tufts composed of a central hypha from which smaller hyphae branch off |

| 5 | Reverse of Petri dish colour darkened | 15 | Aerial mycelium silky: with long and prostrate hyphae |

| 6 | Colony smooth and/or appressed and/or pellicular | 16 | Aerial mycelium subfelty: colony with a thin and prostrate mat, usually hardly visible |

| 7 | Aerial mycelium cottony: with hyphae spreading in all directions | 17 | Aerial mycelium velvety: with short and erected hyphae appressed together |

| 8 | Colony crusty, usually dark in colour | 18 | Aerial mycelium wooly: colony matted with long hyphae or groups of hyphae |

| 9 | Aerial mycelium downy: with short erected hyphae sparsely scattered | 19 | Colony mycelium submerged |

| 10 | Colony farinaceous in appearance | ||

| Microscopical Characters | |||

| Code | Description | Code | Description |

| 20 | Hyphae with clamps at all septa | 28 | Cystidia in vegetative mycelium |

| 21 | Hyphae simple-septate | 29 | Short projection or protuberances on cell-wall |

| 22 | Hyphae simple-septate with scattered or rare clamps | 30 | Oil or resinous drops on cell-wall |

| 23 | Hyphae with thin cell-wall | 31 | Hyphal knots or tangles |

| 24 | Hyphae with thick cell-wall | 32 | Hyphal swellings |

| 25 | Hyphae with cells closely packed forming a pseudoparenchyma | 33 | Absence of conidia and/or blastoconidia and/or arthrospores and/or chlamydospores |

| 26 | Hyphae with numerous short branches, curved branches or thick-walled nodes | 34 | Presence of conidia and/or blastoconidia and/or arthrospores and/or chlamydospores |

| 27 | Encrusted hyphae or hyphae with crystals | 35 | Presence of anastomosis/hyphal bridges |

| Species | Specimen Code Number (SPG) | Host | Region (Spain) | Geographical Coordinates | N° of Strains | GenBank Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corticioid Fungi | ||||||

| Athelia epiphylla Pers. | 5316 | Quercus pyrenaica (on Hymenochaete tabacina) | Castilla y León | 40°33′57″ N 6°08′08″ W | 1 | OR336245 |

| Botryobasidium asperulum (D.P. Rogers) Boidin | 5367 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 42°53′29″ N 4°29′13″ W | 1 | OR336246 |

| Byssomerulius corium (Pers.) Parmasto | 5425 | Quercus ilex | Castilla y León | 41°08′10″ N 5°28′47″ W | 1 | OR336247 |

| Crustomyces subabruptus (Bourdot and Galzin) Jülich | 5387, 5400 | Fagus sylvatica | Cantabria | 43°07′37″ N 4°17′29″ W 43°06′21″ N 4°16′30″ W | 2 | OR336248 OR336249 |

| Efibula tuberculata (P. Karst.) Zmitr. and Spirin | 5315, 5368 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 42°53′29″ N 4°29′13″ W 40°33′57″ N 6°08′08″ W | 2 | OR336250 OR336251 |

| Gloeocystidiellum clavuligerum (Höhn. and Litsch.) Nakasone | 5392 | Corylus avellana (on Hymenochaete corrugata) | Cantabria | 43°07′37″ N 4°17′29″ W | 1 | OR336252 |

| Hericium erinaceus (Bull.) Pers. | 5459, 5462, 5472 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°21′09″ N 6°46′51″ W | 1 | OR336253 |

| Hymenochaete rubiginosa (Dicks.) Lév. | 5312 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°33′57″ N 6°08′08″ W | 1 | OR336254 |

| Hyphoderma mutatum (Peck) Donk | 5372 | Fagus sylvatica | Castilla y León | 43°02′31″ N 4°27′51″ W | 1 | OR336255 |

| Hyphoderma transiens (Bres.) Parmasto | 5402 | Fagus sylvatica | Cantabria | 43°07′37″ N 4°17′29″ W | 1 | OR336256 |

| Megalocystidium leucoxanthum (Bres.) Jülich | 5413, 5427, 5429 | Quercus ilex | Castilla y León | 41°08′10″ N 5°28′47″ W | 1 | OR336257 |

| Merulius tremellosus Schrad. | 5357 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 42°53′29″ N 4°29′13″ W | 1 | OR336258 |

| Peniophora quercina (Pers.) Cooke | 5311, 5318 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°33′57″ N 6°08′08″ W | 1 | OR336259 |

| Peniophorella praetermissa (P. Karst.) K.H. Larss. | 5366 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 42°53′29″ N 4°29′13″ W | 1 | OR336260 |

| Phanerochaete sordida (P. Karst.) J. Erikss. and Ryvarden | 5342 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 42°53′29″ N 4°29′13″ W | 1 | OR336261 |

| Phlebia rufa (Pers.) M.P. Christ. | 5323, 5370 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 42°53′29″ N 4°29′13″ W | 2 | OR336262 OR336263 |

| Phlebiopsis crassa (Lév.) Floudas and Hibbett | 5344, 5363 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 42°53′29″ N 4°29′13″ W | 1 | OR336264 |

| Porostereum spadiceum (Pers.) Hjortstam and Ryvarden | 5356, 5358 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 42°53′29″ N 4°29′13″ W | 1 | OR336265 |

| Radulomyces molaris (Chaillet ex Fr.) M.P. Christ. | 5343, 5364 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 42°53′29″ N 4°29′13″ W | 2 | OR336266 OR336267 |

| Sertulicium granuliferum (Hallenb.) Spirin and Volobuev | 5378 | Fagus sylvatica | Cantabria | 43°06′21″ N 4°16′30″ W | 1 | OR336268 |

| Stereum gausapatum (Fr.) Fr. | 5419 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°33′57″ N 6°08′08″ W | 1 | OR336269 |

| Stereum hirsutum (Willd.) Pers. | 5314, 5418 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°33′57″ N 6°08′08″ W | 1 | OR336270 |

| Stereum subtomentosum Pouzar | 5379 | Fagus sylvatica | Cantabria | 43°06′21″ N 4°16′30″ W | 1 | OR336271 |

| Tulasnella violea (Quél.) Bourdot and Galzin | 5340 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°32′58″ N 6°08′21″ W | 1 | OR336272 |

| Vuilleminia comedens (Nees) Maire | 5322 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°33′57″ N 6°08′08″ W | 1 | OR336273 |

| Vuilleminia coryli Boidin, Lanq. and Gilles | 5381 | Corylus avellana | Cantabria | 43°06′21″ N 4°16′30″ W | 1 | OR336274 |

| Xenasmatella vaga (Fr.) Stalpers | 5371 | Fagus sylvatica | Castilla y León | 43°02′31″ N 4°27′51″ W | 1 | OR336275 |

| Polyporoid fungi | ||||||

| Ceriporia reticulata (Hoffm.) Domanski | 5320 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°33′57″ N 6°08′08″ W | 1 | OR336276 |

| Daedaleopsis confragosa (Bolton) J. Schröt. | 5386 | Fagus sylvatica | Cantabria | 43°06′21″ N 4°16′30″ W | 1 | OR336277 |

| Dichomitus campestris (Quél.) Domanski and Orlicz | 5306 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°33′57″ N 6°08′08″ W | 1 | OR336278 |

| Fomitopsis pinicola (Sw.) P. Karst. | 5348, 5398 | Fagus sylvatica | Cantabria | 43°07′37″ N 4°17′29″ W | 1 | OR336279 |

| Gloeoporus dichrous (Fr.) Bres. | 5307, 5308 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°33′57″ N 6°08′08″ W | 1 | OR336280 |

| Grifola frondosa (Dicks.) Gray | 5436 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°21′09″ N 6°46′51″ W | 1 | OR336281 |

| Hapalopilus rutilans (Pers.) Murrill | 5309, 5313, 5314, 5315, 5316 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°33′57″ N 6°08′08″ W | 1 | OR336282 |

| Irpex lacteus (Fr.) Fr. | 5345 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 42°53′29″ N 4°29′13″ W | 1 | OR336283 |

| Mycoacia gilvescens (Bres.) Zmitr. | 5401 | Fagus sylvatica | Cantabria | 43°07′37″ N 4°17′29″ W | 1 | OR336284 |

| Steccherinum bourdotii Saliba and A. David | 5380, 5385 | Fagus sylvatica | Cantabria | 43°06′21″ N 4°16′30″ W | 1 | OR336285 |

| Steccherinum fimbriatum (Pers.) J. Erikss. | 5369 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 42°53′29″ N 4°29′13″ W | 1 | OR336286 |

| Steccherinum ochraceum (Pers. ex J.F. Gmel.) Gray | 5360, 5417 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 42°53′29″ N 4°29′13″ W | 1 | OR336287 |

| Trametes betulina (L.) Pilát | 5384 | Fagus sylvatica | Cantabria | 43°06′21″ N 4°16′30″ W | 1 | OR336288 |

| Trametes versicolor (L.) Lloyd | 5382 | Fagus sylvatica | Cantabria | 43°06′21″ N 4°16′30″ W | 1 | OR336289 |

| Trichaptum abietinum (Pers. ex J.F. Gmel.) Ryvarden | 5406 | Pinus sylvestris | Cantabria | 43°02′48″ N 4°12′48″ W | 1 | OR336290 |

| Trichaptum biforme (Fr.) Ryvarden | 5439 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°21′09″ N 6°46′51″ W | 1 | OR336291 |

| Truncospora atlantica (Berk.) Spirin and Vlasák | 5390 | Arbutus unedo | Asturias | 43°23′50″ N 4°31′57″ W | 1 | OR336292 |

| Xylodon nespori (Bres.) Hjortstam and Ryvarden | 5396 | Corylus avellana | Cantabria | 43°07′37″ N 4°17′29″ W | 1 | OR336293 |

| Xylodon paradoxus (Schrad.) Chevall. | 5317, 5319 | Quercus pyrenaica | Castilla y León | 40°33′57″ N 6°08′08″ W | 1 | OR336294 |

| Xylodon spathulatus (Schrad.) Kuntze | 5328 | Pinus sylvestris | Castilla y León | 40°32′52″ N 6°08′33″ W | 1 | OR336295 |

| Agaricoid fungi | ||||||

| Pleurotus eryngii var. ferulae (Lanzi) Sacc. | 5411 | Ferula communis | Castilla y León | 41°06′28″ N 6°43′35″ W | 1 | OR336296 |

| Pleurotus pulmonarius (Fr.) Quél. | 5388 | Fagus sylvatica | Cantabria | 43°06′21″ N 4°16′30″ W | 1 | OR336297 |

| Schizophyllum commune Fr. | 5430 | Populus tremula | Castilla y León | 40°57′48″ N 5°41′00″ W | 1 | OR336298 |

| Species | Cultural Characters | Hyphal Width (µm) | Photos of the Colonies in MEA | Notes | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athelia epiphylla (SPG 5316) | 1, 2, 4, 11, 16, 22, 23, 24, 33, 35 | 2.0–5.0 |  |  Presence of brown sclerotia | [36] |

| Botryobasidium asperulum (SPG 5367) | 2, 5, 6, 8, 9, 21, 22, 24, 32, 33 | 5.0–8.0 |  | ||

| Byssomerulius corium (SPG 5425) | 1, 4, 6, 7, 9, 16, 18, 21, 23, 24, 31, 32, 33 | 2.0–5.0 |  | ||

| Ceriporia reticulata (SPG 5320) | 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 18, 21, 23, 32, 33 | 2.5–17.0 |  |  Very noticeable hyphal swellings | [36] |

| Crustomyces subabruptus (SPG 5387) | 1, 5, 12, 14, 18, 20, 23, 24, 26, 27, 33 | 1.5–7.0 |  | ||

| Daedaleopsis confragosa (SPG 5386) | 1, 2, 5, 7, 11, 22, 23, 26, 33 | 1.0–2.5 |  | [35,36,38] | |

| Dichomitus campestris (SPG 5306) | 2, 5, 6, 7, 9, 19, 20, 23, 24, 26, 32, 33 | 1.5–5.0 |  | [24] | |

| Efibula tuberculata (SPG 5315) | 1, 3, 6, 9, 22, 23, 24, 25, 27, 32, 33 | 2.0–10.0 |  | [36] | |

| Fomitopsis pinicola (SPG 5398) | 1, 4, 7, 11, 18, 20, 23, 33 | 1.0–3.0 |  | [24,35,36,38,39] | |

| Gloeocystidiellum clavuligerum (SPG 5392) | 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 10, 20, 23, 24, 26, 32, 33 | 2.0–3.5 |  | [40] | |

| Gloeoporus dichrous (SPG 5307) | 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 20, 23, 32, 33 | 1.5–4.0 |  | [35,36] | |

| Grifola frondosa (SPG 5436) | 1, 3, 7, 11, 18, 22, 23, 24, 33 | 2.0–3.0 |  | [24,36] | |

| Hapalopilus rutilans (SPG 5309) | 1, 2, 4, 9, 10, 16, 22, 23, 34 | 2.0–4.0 |  |  Presence of blastoconidia | [35,36,38] |

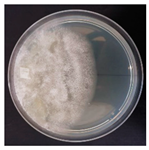

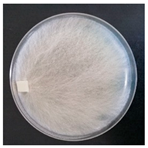

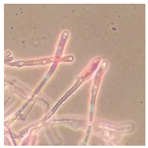

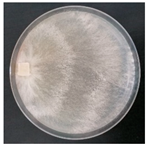

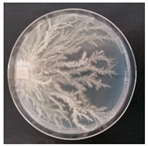

| Hericium erinaceus (SPG 5459) | 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 12, 20, 23, 24, 30, 33 | 2.0–8.0 |  | ||

| Hymenochaete rubiginosa (SPG 5312) | 2, 5, 7, 18, 21, 23, 24, 34 | 2.0–5.0 |  |  Pigmented hyphae and terminal chlamydospores | [36] |

| Hyphoderma mutatum (SPG 5372) | 1, 4, 6, 9, 18, 20, 23, 24, 32, 34 | 2.5–5.0 |  |  Formation of basidia in vegetative mycelium | [35,36] |

| Hyphoderma transiens (SPG 5402) | 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 15, 20, 23, 24, 33, 35 | 2.0–5.0 |  | ||

| Irpex lacteus (SPG 5345) | 1, 3, 4, 7, 18, 21, 23, 24, 32, 33, 35 | 1.2–7.0 |  | [24,36,39] | |

| Megalocystidium leucoxanthum (SPG 5413) | 1, 5, 9, 10, 11, 21, 23, 24, 32, 33 | 2.0–5.0 |  | Absence of clamps, probably due to isolation from spores leading to monokaryon mycelium | [36] |

| Merulius tremellosus (SPG 5357) | 1, 4, 6, 7, 9, 21, 23, 24, 30, 32, 33 | 2.0–7.0 |  | [36,39] | |

| Mycoacia gilvescens (SPG 5401) | 1, 4, 6, 9, 14, 20, 23, 24, 27, 34 | 2.0–7.5 |  | ||

| Peniophora quercina (SPG 5318) | 1, 5, 7, 22, 23, 24, 26, 33 | 1.5–5.0 |  | [24,39] | |

| Peniphorella praetermissa (SPG 5366) | 1, 3, 7, 11, 18, 20, 23, 24, 26, 27, 32, 34 | 2.5–6.0 |  | [36] | |

| Phanerochaete sordida (SPG 5342) | 1, 3, 6, 16, 21, 23, 24, 27, 34 | 2.5–8.0 |  | [36] | |

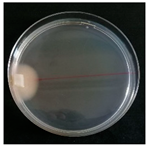

| Phlebia rufa (SPG 5370) | 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 32, 34 | 2.0–7.5 |  |  Presence of gloeocystidia in vegetative mycelium | [24,36] |

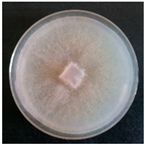

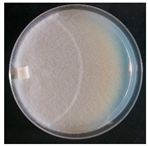

| Phlebiopsis crassa (SPG 5363) | 1, 4, 7, 16, 21, 23, 24, 27, 33 | 1.0–7.5 |  | ||

| Pleurotus eryngii var. ferulae (SPG 5411) | 1, 3, 7, 11, 20, 23, 33 | 2.0–3.0 |  | ||

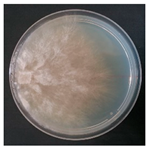

| Pleurotus pulmonarius (SPG 5388) | 1, 3, 7, 11, 22, 23, 31, 34 | 1.0–3.0 |  | ||

| Porostereum spadiceum (SPG 5356) | 1, 2, 4, 7, 18, 20, 23, 24, 26, 30, 33 | 1.5–5.0 |  | [24] | |

| Radulomyces molaris (SPG 5343) | 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 20, 23, 24, 26, 32, 33, 35 | 2.0–3 |  | [36] | |

| Schizophyllum commune (SPG 5430) | 1, 3, 4, 7, 11, 20, 23, 24, 29, 34 | 2.0–5.0 |  | [24,35,36,38,41] | |

| Sertulicium granuliferum (SPG 5378) | 1, 2, 3, 6, 14, 20, 23, 30, 32, 34 | 2.0–7.0 |  | ||

| Steccherinum bourdotii (SPG 5380) | 1, 2, 4, 6, 9, 10, 20, 23, 24, 33 | 2.0–7.0 |  | ||

| Steccherinum fimbriatum (SPG 5369) | 1, 3, 7, 12, 22, 23, 24, 32, 33 | 2.5–5.0 |  | [36] | |

| Steccherinum ochraceum (SPG 5360) | 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 16, 20, 23, 24, 26, 30, 32, 33 | 2.0–7.0 |  | [36] | |

| Stereum gausapatum (SPG 5419) | 1, 2, 3, 7, 11, 12, 22, 23, 24, 30, 33 | 2.0–7.5 |  | [36] | |

| Stereum hirsutum (SPG 5314) | 1, 2, 5, 7, 12, 16, 18, 22, 23, 24, 30, 33, 35 | 2.0–6.0 |  | [24,36,38,41] | |

| Stereum subtomentosum (SPG 5379) | 1, 5, 7, 12, 22, 23, 24, 30, 33 | 2.0–5.0 |  | [36] | |

| Trametes betulina (SPG 5384) | 1, 3, 7, 11, 12, 17, 20, 23, 24, 33 | 1.5–3.0 |  | [24,35,36,39,41] | |

| Trametes versicolor (SPG 5382) | 1, 4, 7, 16, 18, 20, 23, 24, 27, 33 | 2.0–3.0 |  | [24,35,36,39,41] | |

| Trichaptum abietinum (SPG 5406) | 1, 3, 6, 7, 12, 16, 20, 23, 26, 27, 31, 32, 33 | 2.0–5.0 |  | [24,35,36] | |

| Trichaptum biforme (SPG 5439) | 1, 4, 5, 18, 20, 23, 24, 33 | 2.0–5.0 |  | [42] | |

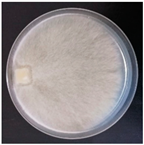

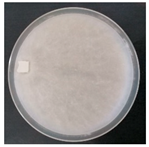

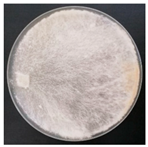

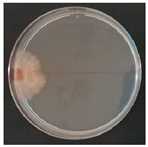

| Truncospora atlantica (SPG 5390) | 1, 2, 5, 7, 9, 10, 11, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 31, 33 | 2.0–5.0 |  | [24] | |

| Tulasnella violea (SPG 5340) | 1, 2, 4, 7, 11, 18, 20, 23, 24, 30, 32, 33, 35 | 2.0–5.0 |  | [36] | |

| Vuilleminia comedens (SPG 5322) | 1, 4, 12, 19, 22, 23, 27, 33 | 1.5–3.0 |  | [36] | |

| Vuilleminia coryli (SPG 5381) | 1, 3, 7, 11, 20, 23, 32, 34 | 2.5–5.0 |  | ||

| Xenasmatella vaga (SPG 5371) | 1, 2, 56, 9, 10, 20, 23, 26, 32, 33 | 1.5–4.0 |  | [36] | |

| Xylodon nespori (SPG 5396) | 1, 3, 6, 9, 20, 23, 26, 31, 33 | 2.0–5.0 |  | ||

| Xylodon paradoxus (SPG 5317) | 1, 4, 7, 9, 18, 20, 23, 32, 34 | 1.5–3.0 |  | Presence of blastoconidia | [36] |

| Xylodon spathulatus (SPG 5328) | 1, 3, 6, 9, 20, 23, 24, 27, 34 | 1.5–3.5 |  | Colony almost transparent; presence of blastoconidia |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Buratti, S.; Girometta, C.E.; Savino, E.; Gorjón, S.P. An Example of the Conservation of Wood Decay Fungi: The New Research Culture Collection of Corticioid and Polyporoid Strains of the University of Salamanca (Spain). Forests 2023, 14, 2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14102029

Buratti S, Girometta CE, Savino E, Gorjón SP. An Example of the Conservation of Wood Decay Fungi: The New Research Culture Collection of Corticioid and Polyporoid Strains of the University of Salamanca (Spain). Forests. 2023; 14(10):2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14102029

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuratti, Simone, Carolina Elena Girometta, Elena Savino, and Sergio Pérez Gorjón. 2023. "An Example of the Conservation of Wood Decay Fungi: The New Research Culture Collection of Corticioid and Polyporoid Strains of the University of Salamanca (Spain)" Forests 14, no. 10: 2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14102029

APA StyleBuratti, S., Girometta, C. E., Savino, E., & Gorjón, S. P. (2023). An Example of the Conservation of Wood Decay Fungi: The New Research Culture Collection of Corticioid and Polyporoid Strains of the University of Salamanca (Spain). Forests, 14(10), 2029. https://doi.org/10.3390/f14102029