Critical Aspects of People’s Participation in Community-Based Forest Management from the Case of Van Panchayat in Indian Himalaya

Abstract

1. Background

1.1. Introduction

1.2. Context

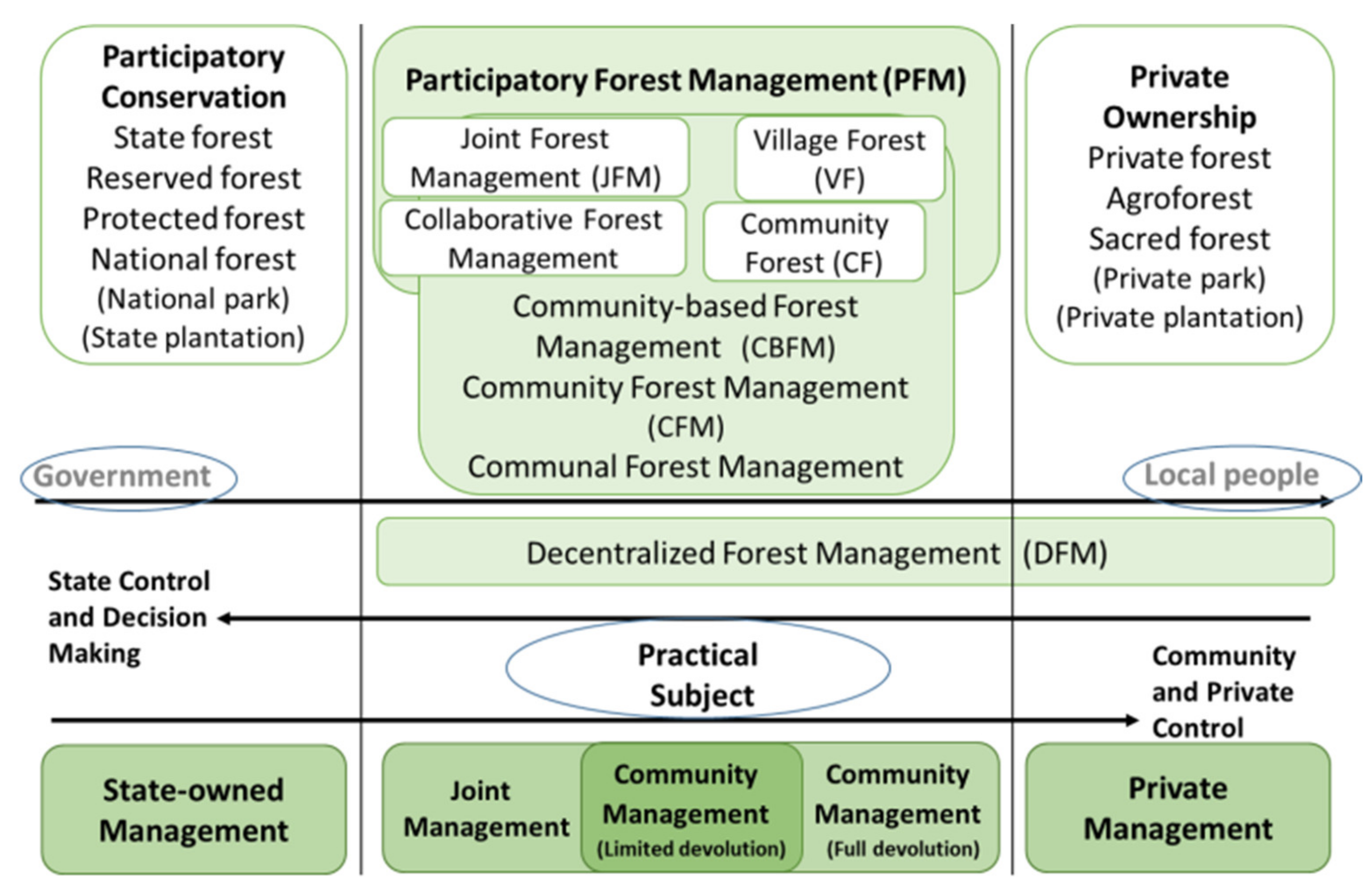

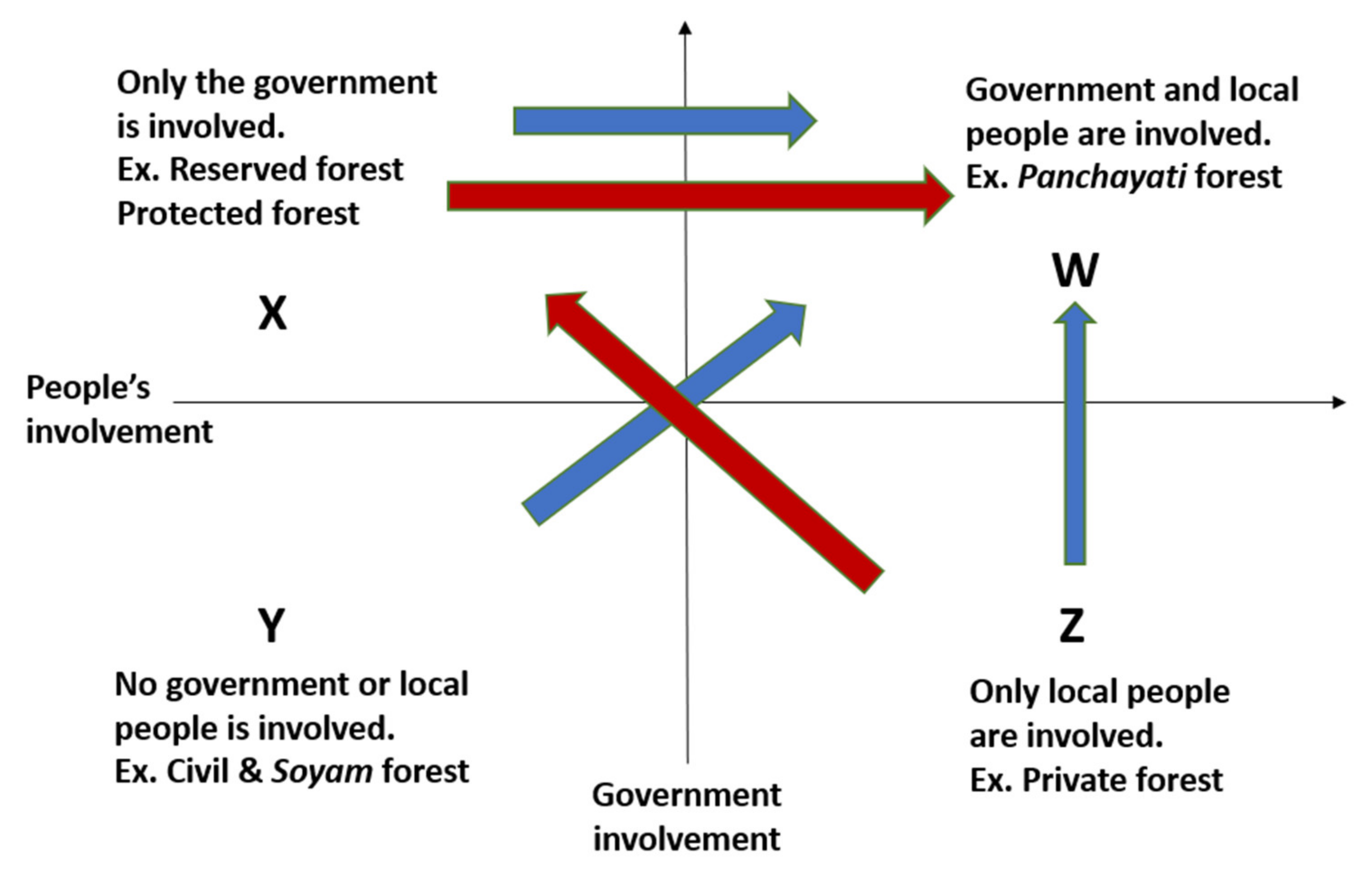

1.2.1. Participatory Forest Management (PFM)

1.2.2. CBFM in Developing Countries

1.2.3. National Forest Policy and CBFM in India and Uttarakhand

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature and Statistical Collection

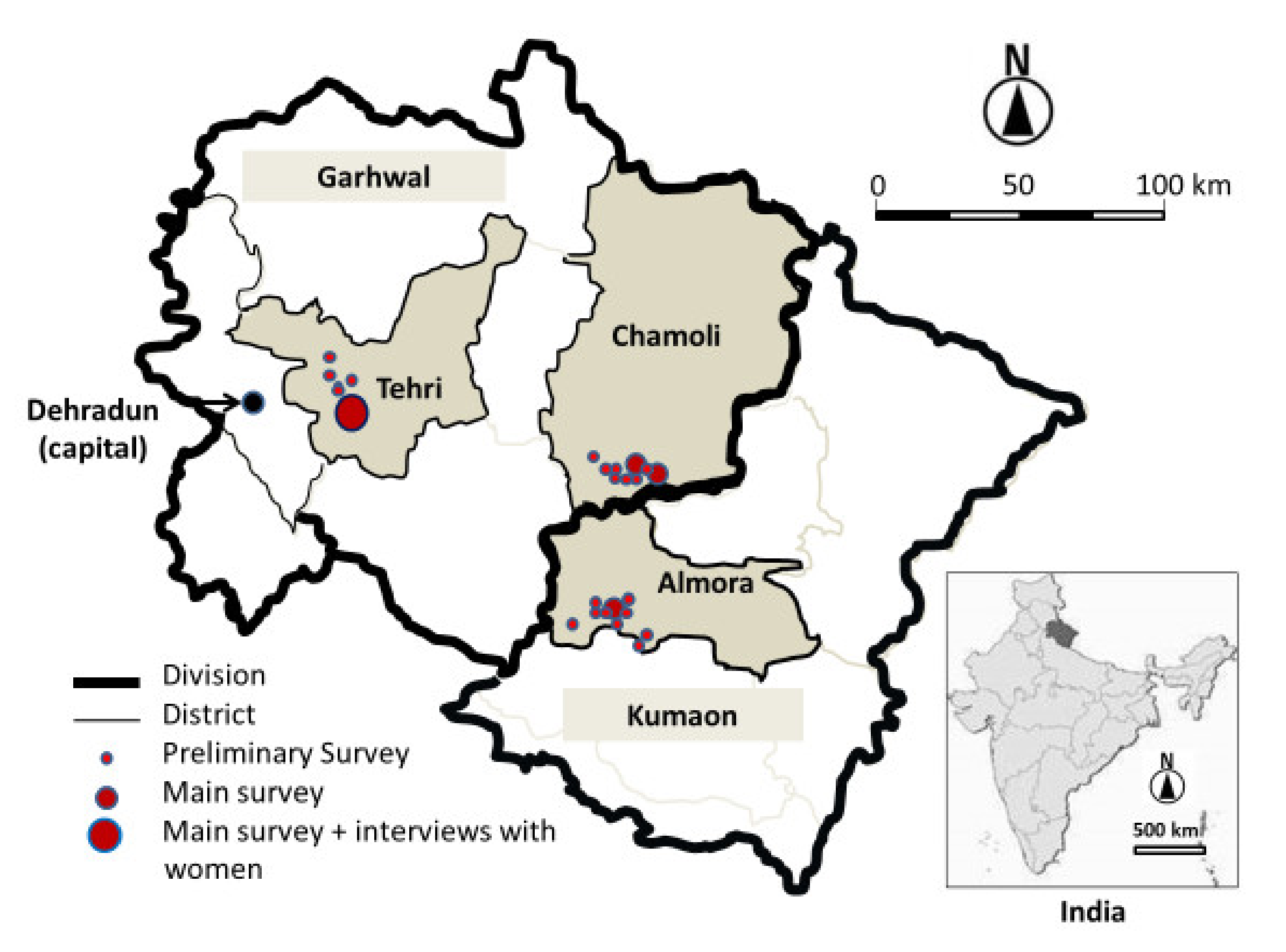

2.2. Preliminary Investigation and Case Selection

2.3. Survey Description, Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Investigation of the VPs in the 4 Villages

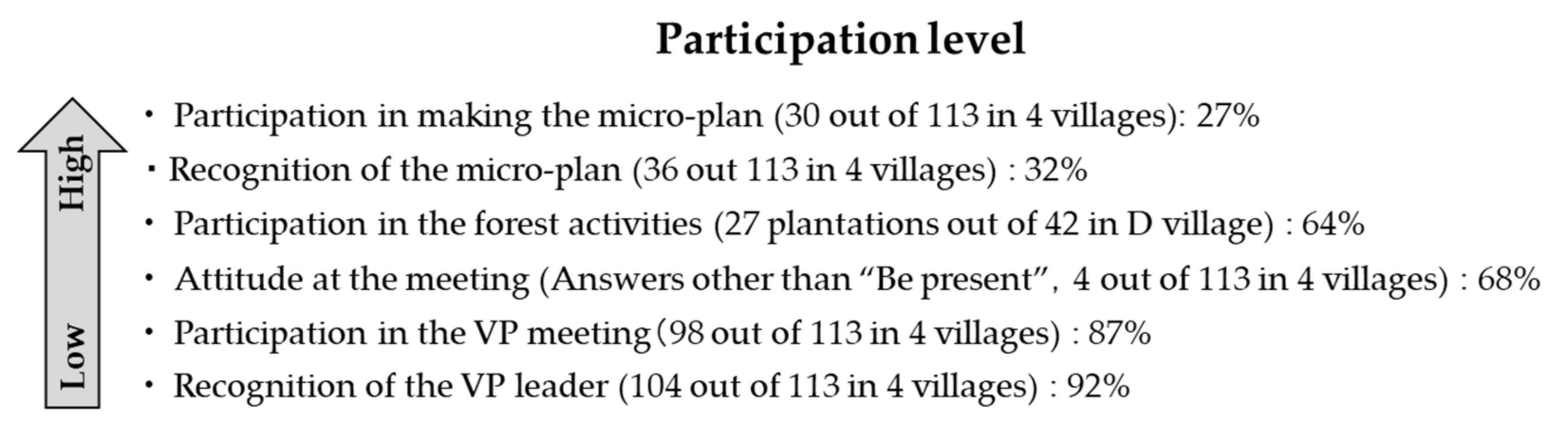

3.2. Local Peoples’ Participation in Forest Management

3.3. Forms of Participation at the Meetings

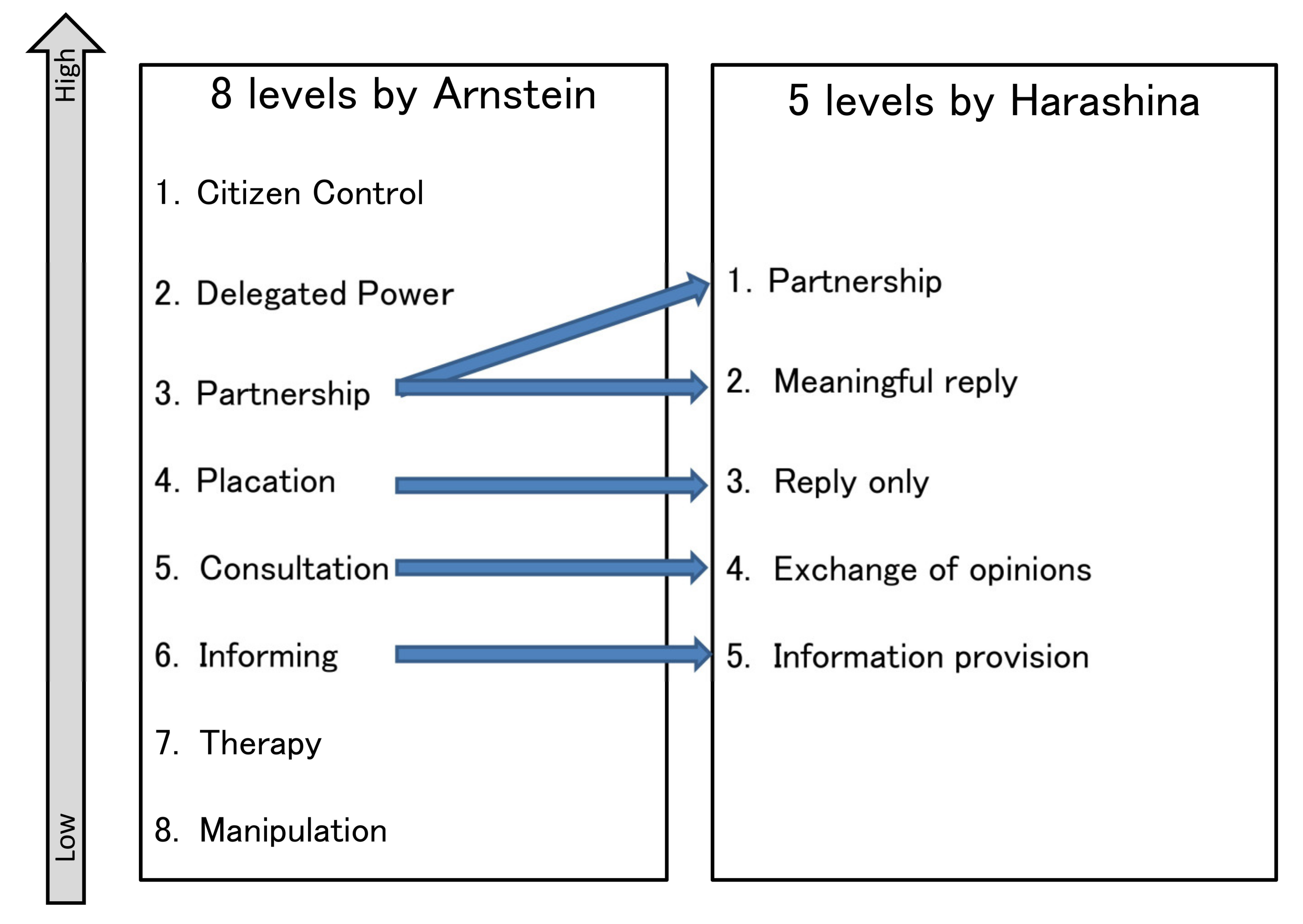

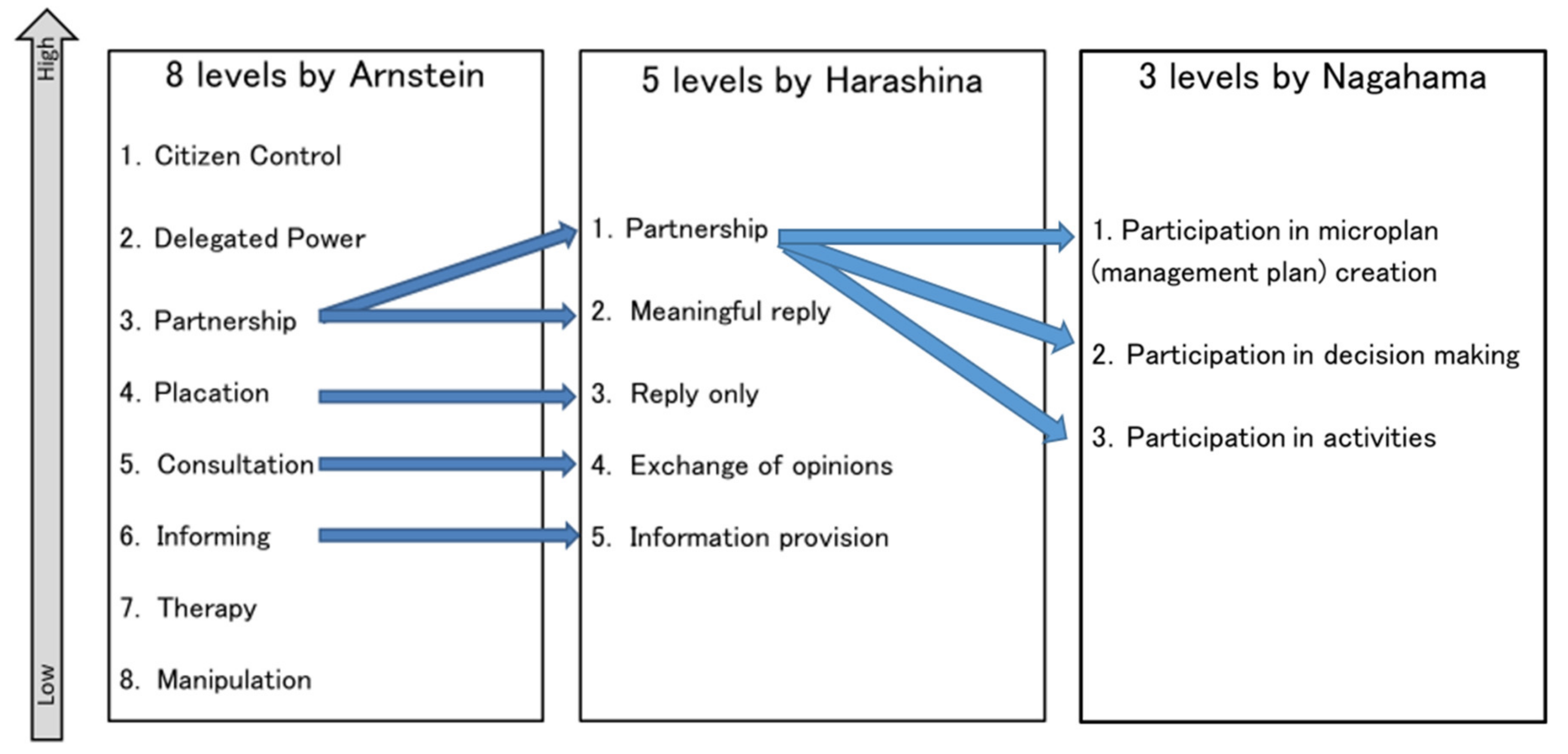

3.4. Level or Stage of Participation in Forest Management

3.5. Forest Usage by Women and Their Participations in the Management Committee

3.5.1. Interviews with the Women who Are MC Members

3.5.2. Interviewing with the Women who Are NOT MC Members

3.6. Factors That Prevent People from Becoming MC Members

4. Discussion

4.1. Van Panchayat (VP): Pioneering Case Study of CBFM

4.2. Categories in Participation

4.3. Participation Level and Form

4.4. Decision-Making by Women

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gilmour, D. Forty Years of Community-Based Forestry—A Review of Its Extent and Effectiveness; FAO: FAO FORESTRY PAPER 176; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Duguma, L.A.; Atela, J.; Ayana, A.N.; Alemagi, D.; Mpanda, M.; Nyago, M.; Minang, P.A.; Nzyoka, J.M.; Foundjem-Tita, D.; Ntamag-Ndjebet, C.N. Community forestry frameworks in sub-Saharan Africa and the impact on sustainable development. Ecol. Soc. 2018, 23, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balooni, K.; Ballabh, K.; Inoue, M. Declining instituted collective management practices and forest quality in the Central Himalayas. Econ. Political Wkly. 2007, 42, 1443–1452. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, A.; France, M.; Purdy, L.; Karver, J. The Extent and Potential Scope of Community and Small holder Forest Management and Enterprises. Right Resour. Initiat. 2011. Available online: https://rightsandresources.org/wp-content/exported-pdf/forestmanagementfinaljan28.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Ameha, A.; Larsen, H.O.; Lemenih, M. Participatory forest management in Ethiopia: Learning from pilot projects. Environ. Manag. 2014, 53, 838–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, D.B. Mexico’s Community Forest Enterprises: Success on the Commons and the Seeds of a Good Anthropocene; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel, Social Forestry in Latin America 2021. Available online: https://archive.org/details/manualzilla-id-6214047 (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Sugimoto, A.; Pulhin, J.M.; Inoue, M. Is recentralization really dominant? The role of frontline forest bureaucrats for institutional arrangement in the Philippines. Small-Scale For. 2014, 13, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.P. Forest landscapes as social-ecological systems and implications for management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 177, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattnaik, B.K.; Duttaet, S. JFM in South-West Bengal: A Study in Participatory Development. Econ. Political Wkly. 1992, 32, 3225–3232. [Google Scholar]

- Somanathan, E.; Prabhakar, R.; Mehta, B.S. Does decentralization work? Forest conservation in the Himalayas; (Discussion Papers in Economics); Indian Statistical Institute: Delhi, India, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Global Forest Resources Assessment 2020; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lise, W. Factors influencing people’s participation in forest management in India. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 34, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, L.; Sharif, A.; Mukul, S.A.; Gregorio, N.; Herbohn, J. Community-Based Management of Tropical Forests: Lessons Learned and Implications for Sustainable Forest Management; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing Limited: Cambridge, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Muttaqin, M.Z.; Alviya, I.; Lugina, M.; Almuhayat, F.; Hamdani, U.; Indartik. Developing community-based forest ecosystem service management to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 108, 101938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, R.; Todoet, Y. Impact of community-based forest management on forest protection: Evidence from an aid-funded project in Ethiopia. Environ. Manag. 2012, 3, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harashima, Y. Citizen Participation and Consensus Building: Planning for Cities and the Environment; Gakugei Shuppansha: Kyoto, Japan, 2005; pp. 11–40. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, M. Participatory Forest Management: First Strategic Research Report (Forest Conservation Project); Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES): Kanagawa, Japan, 2001; pp. 34–58. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, M. Importance and prospects of local community participation in forest management. In Forest Loss and Conservation in Asia; Inoue, M., Ed.; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES); Chuohoki Publishing: Tokyo, Japan, 2003; pp. 309–324. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Forest 2020: Forests, Biodiversity and People; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Meinzen-Dick, R.; Knox, A. Collective action, property regimes, and devolution of natural resource management: A conceptual framework. In Collective Action, Property Regimes, and Devolution of Natural Resources Management: Change of Knowledge and Implications for Policy; Meinzen-Dick, R., Knox, A., Di Gregorio, M., Eds.; DES/ZEL: Feldafing, Germany, 2001; pp. 41–73. [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi, H. Effectiveness of participatory forest management in semi-arid land: A case study of Myanmar common forest and Kenya social forestry. Doctoral Dissertation, Department of International Agricultural Science, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Japan, Tokyo, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi, H. A typology of participatory forest management: Focusing on changes in government involvement and community involvement. For. Econ. 2015, 68, 61–78. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kato, T. Social Forestry (2) Development of Methods to Promote Community Participation. Trop. For. 1999, 47, 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, M.; Mishiba, J. Creation of forest land and its changing role in India. University of Tsukuba. Agric. For. Res. Cent. Exp. For. Rep. 2003, 19, 1–40. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Saito-Jensen, M. Do Local Villagers Gain from Joint Forest Management? Why and Why Not? Lessons from Two Case Study Areas from Andhra Pradesh, India; 2007 JICA Visiting Fellow Research Report; Japan International Cooperation Agency: Tokyo, Japan, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ballabh, V.; Balooni, K.; Dave, S. Why local resources management institutions decline: A comparative analysis of Van (Forest) Panchayats and Forest Protection Committees in India. World Dev. 2002, 30, 2153–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarin, M.; Neera, M.S.; Sundar, N.; Bhogal, R.K. Devolution as a threat to democratic decision-making in forestry? Findings from three States in India. In Local Forest Management: The Impacts of Devolution Policies; Edmunds, D., Wollenberg, E., Eds.; Earthscan: London/Sterling, UK, 2003; pp. 55–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kano, K. Local peoples’ Movements and the state in India: Forest use and forest policy. Conflicts and Movements. Bunka Anthropol. 1997, 6, 201–227. (In Japanese). Available online: http://webcatplus.nii.ac.jp/webcatplus/details/work/3070490.html (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Gairola, H.; Negi, A.S. VPs in Uttarakhand: A perspective from practitioners. Community Based Biodiversity Conservation in the Himalayas; Gokhale, Y., Negi, A.K., Eds.; The Energy and Resource Institute: New Delhi, India, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kodama, T. Designated Tribes and Poverty in the Forest Areas of India. J. Econ. Ryukoku Univ. 2009, 49, 17–33. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Nose, M. The role of panchayats and NGOs in regional development measures in India. Himal. Stud. J. 2013, 14, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Scheyvens, H.; Hyakumura, K.; Seki, Y. Forest governance in a state of transition: Overview of transition, analytical framework, summaries of county studies and synthesis. In Decentralization and State-Sponsored Community Forestry in Asia: Seven Country Studies of Transitions in Forest Governance, Contemporary Forest Management and the Prospects for Communities to and from Benefit from Sustainable Forest Management; IGES (Institute for Global Environmental Strategies): Hayama, Japan, 2007; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Nagahama, K.; Saito, K.; Masuda, M.; Ota, M.; Gairola, H.; Kala, S.K.; Rakwal, R. Forest commons use in India: A case study of Van Panchayat in the Himalayas reveals people’s perception and characteristics of management committee. Environ. Ecol. Res. 2016, 4, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- USG. The Uttaranchal Panchayat: Forest Rules 2005; Uttaranchal State Government: Dehradun, India, 2005. (In Hindi) [Google Scholar]

- Nagahama, K.; Satya, L.; Saito, K. The Van Panchayat movement and struggle for achieving sustainable management of the forest: A case study of Uttarakhand in North India. SDRP J. Earth Sci. Environ. Stud. 2016, 1, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Nagahama, K.; Saito, K.; Yamamoto, H.; Hama, Y.; Gairola, H.; Dhaila, P.; Rakwal, R. How Van Panchayat rule systems and resource use influence people’s participation in forest commons in the Indian Himalayas. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 12, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UFD. Uttarakhand Forest Statistics 2010–2011, 2011–2012, 2012–2013, 2013–2014, 2014–2015, 2015–2016, 2016–2017, 2017–2018; Uttarakhand Forest Department: Dehradun, India, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar]

- USG. Van Panchayats Atlas; Uttaranchal State Government: Dehradun, India, 2007. (In Hindi) [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- MDO. Micro-Plan in D village 2003–2007; Mussoorie Divisional Office: Uttarakhand, India, 2002. (In Hindi) [Google Scholar]

- LPFD. Micro Implementation from Year 2012–2013 to 2016–2017 Kwilakh; Garsain Land Protection Forest Division: Uttarakhand, India, 2011. (In Hindi) [Google Scholar]

- Yamauchi, H. The Significance of Government Interventions in Local Communities ’Forest Management on Customary and Private Lands: A Case Study of Meghalaya State in India. For. Econ. 2021, 74, 1–18. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, M. Multifaceted Significance of Collaborative Governance and Its Future Challenges, In Collaborative Governance of Forests: Towards Sustainable Forest Resource Utilization; Tanaka, M., Inoue, M., Eds.; University of Tokyo Press: Tokyo, Japan, 2015; pp. 311–334. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, A. Environmentality: Technology of Government and the making of Subjects; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, B. Gender and forest conservation: The impact of female’s participation in community forest governance. Ecol. Econ. 2009, 68, 2785–2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miea, M.; Shiva, V. Ecofeminism: Critique Influence Change; ZedBooks: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, M.; Krishnamurthy, R. If there is jangal (forest), there is everything: Exercising stewardship rights and responsibilities in van panchayat community forests, Johar Valley, Uttarakhand, India. In Routledge Handbook of Community Forestry; Bulkan, J., Palmer, J., Larson, A.M., Hobley, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 372–395. [Google Scholar]

| Technical Terms | Practical Content (Approach) | Countries | Age of Practice and Areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social Forestry | Local residents take the initiative in everything from planning to maintenance of tree planting and forest land development. In terms of maintenance of plantations, capacity building of residents, consideration for the vulnerable, etc., is based on the local community | India Thailand The Philippines Indonesia Latin American countries | Since 1970s, Social Forestry 1992~1998, North East Thailand Afforestation Promotion Plan Since 1982, Integrated Social Forestry Program (ISFP) Since 1972 Tumpang sari Program (Java Forestry Corporation) ICDP (Integrated Conservation and Development Projects) |

| 2. Community-based Forest Management (CBFM) | Community, which is leading the management, is the only forest conservator and its beneficiary. The government is only in a position to assist aspects such as morals | Nepal The Philippines | Since 1978, Community Forest Program: Panchayat Forest and Panchayat Conservation Forest Since 1989, Community Forestry Program |

| 3. Participatory Forest Management (PFM) | Government manages the forest and distributes its profits with the cooperation of the community, but most of the profits belong to the government | Tanzania Ethiopia | Since 1990 Since 1995 |

| 4. Joint Forest Management (JFM) | Government and the community will work together to manage the forest and share the costs and benefits of practice | India African countries | Since 1990, all over JFM India Since the 1990s |

| 5. Collaborative Forest Management: (CFM) | Government (Forestry Corporation) and residents will work together equally. Residents can enjoy the benefits of mutual partnership | Mexico Indonesia | Since 1980, Forest Resources Conservation and Sustainable Management Project (PROCYMAF) Since 2001, Collaborative Forest Management (PHBM) |

| 6. Decentralized Forest Management (DFM) | Delegation of forest management from government to the village community | Included technical terms of 1~5 |

| Types of Participation | People’s Participation | Classification of Participatory | Policy Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Informing | The results determined by outside experts are communicated to the residents. One-way communication from outside to residents. | Participatory top-down approach | Blueprint approach that positions local residents as labor, volunteer staff, and funders. |

| (2) Information gathering | Residents answer questions from outside experts. One-way communication from residents to the outside. | ||

| (3) Consultation | External experts consult and discuss with residents through meetings and public hearings. Two-way communication. However, residents cannot participate in analysis and decision making. | ||

| (4) Placation | Residents participate in the decision-making process. However, they cannot participate in major decisions. | Endogenous approach led by an expert | Government has decision-making power. Plans devised by professional planners will be revised through discussions and workshops by residents and citizens. A relatively flexible blue-print approach. Both local people and the government have decision-making power. |

| (5) Partnership | Residents participate in decision-making and collaborative activities in all processes such as preliminary surveys, planning, implementation and evaluation. Participation is a right, not compulsory. | Endogenous bottom-up approach | A kind of learning process approach. Experts are only involved as facilitators. Local residents have the right to make decisions. |

| (6) Self-mobilization | Residents take the initiative and outside experts support it. |

| Plot number | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Average | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VP | D | G | K | M | |||

| Division | Garhwal | Kumaon | Garhwal | Garhwal | - | - | |

| District | Tehri | Almora | Chamoli | Chamoli | - | - | |

| Altitude (m) | 1850 | 1850 | 1450 | 1400 | 1638 | - | |

| HH Number | 51 | 22 | 31 | 26 | 33 | 130 | |

| Sample HH Number | 42 | 14 | 31 | 26 | 28 | 113 | |

| Recovery Rate | 82% | 64% | 100% | 100% | 86% | - | |

| Sample HH Number by Caste) * | SC | 22 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 6.8 | 27 |

| OC | 11 | 2 | 25: Rawat 6: Negi | 1: Bisht 5: Rawat 18: Negi | 6.5 | 13 | |

| Brahmin | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 | 18 | |

| Population | 348 | 158 | 129 | 147.0 | 196 | 782 | |

| Female Population | 181 | 46 | 62 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Male Population | 167 | 72 | 67 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Average Family Number | 6.8 | 7 | 6 | 6.4 | 6 | 25 | |

| Established Year | 1993 | 1937 | 1972 | 1953 | 1964 | - | |

| MC (Gender) | M: 5, F: 4 | M: 5, F: 4 | M: 5, F: 4 | M: 6, F: 3 | M: 5.6, F: 3.8 | M: 21, F: 15 | |

| MC (Caste) | OC: 6, SC: 3 | OC: 6, SC: 3 | OC: 9 | OC: 9 | OC: 7.5, SC: 1.5 | OC: 30, SC: 6 | |

| VP Leader | Male | Female | Male | Male | - | - | |

| Forest Watchman | NO | Male | Female | Male | - | - | |

| Factor | D Village | G Village | K Village | M Village |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recognition of VP Leader (Proportion by dummy variable) | 0.92 | 0.71 | 1.00 | 0.96 |

| Attendance of Meetings (Proportion by dummy variable) | 0.76 | 0.71 | 1.00 | 0.96 |

| Ability to Influence Decisions (Strength based on Likert scale by 5 levels, r: 0 < r < 1) | 0.42 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 0.62 |

| Frequency of Meeting (Participation ratio) | 0.33 | 0.58 | 0.84 | 0.96–1.00 |

| Merit/Benefit of MC Activity (Proportion by dummy variable) | 0.77 | 0.43 | 0.06 | 0.19 |

| Question Number | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question Number | Caste | Age | Final Education | No. of Children | Occupation | Distance of VP Forest | Firewood Collection | LPG (Liquefied Petroleum Gas) | Collection | Fodder Collection | Animal Grazing | VP Member | VP-MC Previous Member | VP-MC Member | Attend VP Meeting | Name of Sarpanch | Power of VPMC | Wish to VPMC | Why? Others, if Specify. |

| Sample No. | (Year) | 1: Agriculture | 1: Yes | 1: Yes | 1: Yes | 1: Yes | 1: Yes | 1: Yes | 1: Yes | 1: Yes | 1: Yes | 1: Yes | |||||||

| 0: No Education | 2: Shop Keeper | 2: No | 2: No | 1: Yes | 2: No | 2: No | 2: No | 2: No | 2: No | 2: No | 2: No | 2: No | |||||||

| 1–5: Elementary 6–13:High School | 3: Teacher | (km) | (Hour/ Week) | 2: No | |||||||||||||||

| 14–15: University, BA | 4: House Wife | ||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | Rajput | 38 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | My husband is a sarpanch presently. |

| 2 | Rajput | 50 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | No time; taking animal, collecting fodder, cooking, agriculture. |

| 3 | Rajput | 45 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Father has gone and mother has to maintain their life. She is not interested in VP. |

| 4 | Brahmin | 32 | 15 | 0 | 2 | 0.3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | No time; managing for her shop and father’s shop. Husband had passed away only 2 years after the marriage. |

| 5 | SC | 30 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | I am not chosen to be MC member, because I am a woman and SC. |

| 6 | SC | 28 | 14 | 3 | 3 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Previous VP member, I had never seen micro-plan, never received money. |

| 7 | SC | 55 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | No interest at all |

| 8 | SC | 40 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | No time; taking animal, colleting fodder, cooking, agriculture. |

| 9 | Chauhan | 38 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 0.3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | I don’t know why I was elected for MC. The process is among men’s discussion. My husband manages hotel and I am staying Delhi with him except for July. |

| 10 | Rajput | 48 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Family member was a member of VP-MC. |

| 11 | Rajput | 35 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | No time; taking animal, collecting fodder, cooking, agriculture. |

| 12 | Brahmin | 40 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | No time; taking animal, collecting fodder, cooking, agriculture. |

| 13 | Brahmin | 64 | 0 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | VP meeting is only for men. | |

| 14 | Brahmin | 47 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | No time; taking animal, collecting fodder, cooking, agriculture. |

| 15 | Brahmin | 29 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | As forest is evergreen. |

| 16 | Brahmin | 64 | 0 | 1 | 0.6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | I retired house work. Now, I only take care of children and do cooking. | |

| 17 | SC | 49 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | I do not know why I am a member of VP. |

| 18 | Rajput | 64 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0.2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | My husband was a sarpanch more than 20 years. |

| 19 | Rajput | 49 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | Forest is like my father. I can get many materials when I go to forest. |

| 20 | SC | 29 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | I am interested in becoming VPMC member, because of Mr. Rawat’s request. I don’t get any money from VP-MC. |

| 21 | Brahmin | 30 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | I don’t know why I was elected for MC, the process is among men’s discussion. There is no MC meeting in this period, MC has no power. I am happy to be elected for MC member again. I will be educated when I can meet many people in the meeting and improve my knowledge. I can comment a lot at the meeting. |

| 22 | SC | 32 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | I don’t have LPG, but firewood user, My husband is in Panjab. No agriculture and animals. Everything comes from market. |

| 23 | SC | 70 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | I am getting old, no interest in VP at all. |

| 24 | SC | 30 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | I am interested in becoming a VP-MC member. |

| 25 | Brahmin | 80 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0.3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | I am too old to attend the VP meeting. |

| 26 | SC | 38 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | I want to be a member, because I hope village activity will be better. |

| 27 | SC | 36 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0.3 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Because my husband attends VP meeting, I am happy to use VP forest. |

| 28 | Brahmin | 50 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | I am an assistant of Pradahan (Community leader). |

| Time | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring/ Sumner/ Autumn (March–May/ October) | Wake-up | Collection from forest | Lunch/ | Agricultural work | Cow-ranch | Dinner and the preparation | Sleep | |||||||||||||||||

| Cow-ranch | Agricultural work | Rest | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Breakfast | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mon-soon | Wake-up | Collection | Cow-ranch | Rest | Agricultural work | Cow-ranch | Dinner and the preparation | Sleep | ||||||||||||||||

| (June– September) | Cow-ranch | from forest | lunch | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Breakfast | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Winter (November– February) | Sleep | Wake-up | Collection | Lunch/ | Agricultural work | Cow-ranch | Dinner and the preparation | Sleep | ||||||||||||||||

| Cow-ranch | from forest | Rest | Rest | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Breakfast | Entertainment | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Year | Participatory Observation | Interview with Mr. R. |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | Introduced Mr. R., by Mr. K., Chief Forest Panchayat, FD | He had been the head of VP since its organization at Village D in 1993. |

| 2012 | Structured interview survey in village D (41 villages), Stay at Mr. R.’s house, Obtaining a micro-plan of village D (MDO 2002) and a hand-drawn map of the village, Visit to Mussoorie Forest Office with Mr. R | The Panchayat forest used to be a civil forest (Civil and Soyam forest). Anyone can access and use the forest freely. As for the rules of use of the forest, cutting of trees is prohibited, but there are no rules regarding the collection of firewood and leaves, or restrictions on branching, grazing, etc. Residents are always free to enter the panchayat forest to collect forest products and graze livestock There is a project site for bamboo forest, waiting for bamboo to take root. There was a bamboo forest project site, waiting for bamboo to take root. Although the species of tree was not required for planting, bamboo was planted in consideration of job creation in the village, as bamboo wood can be used as building material after growing. |

| 2013 February | Meeting with the VP head of village D (Mr. R) and his daughter (Ms. B) at a hotel in the provincial capital, Dehradun | The year 2013 is the year of election of forest management committee members in the forest panchayat. I am proud to have worked as the head of the forest panchayat in village D since the establishment of the forest panchayat in 1993 until 2012. |

| 2013 October | Semi-structured interviews with females, Interviews with new and old VP heads in village D, stay in village D (homestay) | VP head changed in 2013. For those households who were away for the last and current household surveys for the interview, they stayed in other places such as Dehradun or Delhi for work or child education, but returned home several times a year. The new VP chief was recommended by myself The forest warden has not been in village D for some time. There is no need for it. The wife of the second son who lives in the next house is a member of the MC. |

| 2015 | Forest (Trees) investment in Village D | The bamboo project had difficulty in rooting. In the early 2000s, a bamboo plantation project was launched in the state. There was a period of time when a subsidy of Rs 100,000 per year was provided for the preparation of afforestation, for a period of five years, which was paid by the state government to an account managed by the Chief of the VP in the early 2000s. The subsidy also encouraged other villages to implement the project. Village D has not only Panchayat forest but also Uttarakhand forest as well as large Reserved forest. Some of the residents do not know the boundaries. |

| 2017 | Stay in Village D (homestay in Village D) | In Village D, there are no pine forests large enough to collect pine needles from Himalayan pine. |

| 2018 | Interview with new VP head of village D and former VP and head of village D (overnight stay in village D) | In households where there is a male member of the management committee, no adult female can be a member. In the forest management committee, the ratio of male and female members is the same. The previous head did not understand the work well. The new VP chief recommended a man of the same caste who lives nearby. As for the management committee members, we have asked households with women who can serve on the committee to ensure that women make up half of the committee (4 members). |

| 2019 March | Interview with the former VP of Village D and interviews in Village D (Homestay in Village D) | (Regarding the neighboring villages where the interviews were conducted) In village B, there is a forest panchayat chief, but no forest committee meeting is held; in village M, the organization does not seem to be active.Every household (which did not have LPG in the past) is now using LPG. Gas stoves are convenient for boiling water for chai, etc., but for cooking, wood is more convenient because of its higher heat. |

| 2019 October | Participant observation in Village D (Homestay in Village D) | (The north side of the village is the area where the SC residents.) The place beyond (north side) the SC is a garbage dump. Household garbage is usually disposed of by building a fire and burning it by themselves. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nagahama, K.; Tachibana, S.; Rakwal, R. Critical Aspects of People’s Participation in Community-Based Forest Management from the Case of Van Panchayat in Indian Himalaya. Forests 2022, 13, 1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101667

Nagahama K, Tachibana S, Rakwal R. Critical Aspects of People’s Participation in Community-Based Forest Management from the Case of Van Panchayat in Indian Himalaya. Forests. 2022; 13(10):1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101667

Chicago/Turabian StyleNagahama, Kazuyo, Satoshi Tachibana, and Randeep Rakwal. 2022. "Critical Aspects of People’s Participation in Community-Based Forest Management from the Case of Van Panchayat in Indian Himalaya" Forests 13, no. 10: 1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101667

APA StyleNagahama, K., Tachibana, S., & Rakwal, R. (2022). Critical Aspects of People’s Participation in Community-Based Forest Management from the Case of Van Panchayat in Indian Himalaya. Forests, 13(10), 1667. https://doi.org/10.3390/f13101667