1. Introduction

The chemical and enzymatic grafting of wood-protecting agents, such as fungicides and flame retardants, is an interesting research topic that can identify sustainable and environmentally friendly solutions for some of the conventional limitations of wooden materials.

The utilization of laccase, obtained from fungi, for grafting phenols and other compounds, is a technique that has been used for different applications in the forestry industry [

1,

2,

3,

4].

The grafting ability of this enzyme is attributed to the oxidation of wood fiber through the lignin moiety on the cell wall, forming highly reactive radicals that can promote a cross-linking reaction with some of the compounds that are present in the media [

5]. Moreover, the grafting ability of the enzyme could also be produced by the oxidation of a laccase substrate that, subsequently, can migrate and then link to the wood surface.

A recent review in 2018 [

6] not only describes studies on grafting assisted by laccase, but also provides a critical comparison that highlights either the lack or presence of compelling evidence for covalent grafting.

The utilization of laccase is also described for grafting lauryl and octyl gallate onto

Eucalyptus wood to increase its hydrophobicity and, consequently, the wood’s dimensional stability and durability [

7].

The aim of this paper is to evaluate the efficacy of two compounds obtained from the wood of

Eucalyptus spp. as wood preservatives: grafted lignin sulfonate and kraft lignin. These compounds were evaluated alone and with the addition of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). These products were anchored on wooden surfaces via laccase assisted grafting. Comparisons were made with a commercial product manufactured by Renner SpA (Italy) that protects against fungal decay through surface application (in accordance with use class 3, CEN EN 335: 2013 [

8]).

Certainly, the use of use AgNPs for antimicrobial and antifungal protection in wood preservatives [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14] has been attempted. Although the application of AgNPs mainly focuses on viral pathogens and bacteria in humans and animals [

15,

16], there is substantial interest in using them for wood preservatives as well [

17,

18]. The mode of action for AgNPs has already been described in the literature [

19].

On the other hand, lignin is one of the most abundant aromatic biopolymers on Earth and is easily available as a by-product from the pulp industry. It is produced in large amounts and is often burnt due to lack of demand and value. Therefore, several applications have been developed to revalorize it. Wood treatments with lignin are one of these applications; however, it is difficult to find the scientific literature about it, as the review of Huang and Feng (2016) [

20] reflects. Some of the properties of lignin, such as phenolic content, antioxidant activity and metal chelating properties, are interesting for use enhancing wood durability, as Schultz et al. (2005) indicate [

21].

Regarding the enhancement of wood durability, it is important to remark on the properties of both compounds (lignin and AgNPs) that could have synergic effects on wood: AgNPs add biocide properties and lignin avoids the oxidative mechanisms of rot decay fungi. Moreover, lignin can retain AgNPs by interacting with phenolic units, due to its chelating properties. In addition, lignin can be fixed to wood using cross-linking reactions attended by laccase.

Furthermore, the wood industry has been searching for flame retardant treatments with the aim of providing extra safety to their products. Due to the fact that wood is a common material in construction, improving its safety should be considered for the interests of the customers.

Different kinds of flame retardants are found in the market, including those based on physical properties, such as aluminum hydroxide, and those based on radical quenching, such as halogenated compounds. An overview of brominated flame retardants, with information about production, applications and properties, is described in [

22].

Tetrabromobisphenol-A (TBBPA) is widely used in combination with plastic polymers, such as epoxy and polycarbonate resins, high-impact polystyrene, phenolic resins, adhesives and others. In addition, it is registered by the European Chemical Agency (ECHA) as very toxic to aquatic life, with long-lasting effects.

TBBPA is synthesized by the bromination of bisphenol-A in a solvent, such as halocarbon or 50% hydrobromic acid. TBBPA is mainly produced in the USA, Israel and Japan, at a rate of 150.000 tn/year [

23], and its consumption in the EU was 13.800 tn/year at the beginning of 2000 [

24]. At present, it is under assessment as being Persistent, Bioaccumulative and Toxic (PBT list) and as Endocrine Disrupting (ED list) in the ECHA (European Chemical Agency) [

25],

https://echa.europa.eu, accessed on 10 July 2021).

Due to this recognized risk, a procedure to fix TBBPA in wood as a flame retardant seems to be a possible way to avoid further environmental impacts. In this case, laccase could perform the fixation of the compound onto the wood in mild conditions. Therefore, as a second objective, this paper reports on the effects of the enzymatic grafting of TBBPA onto wood in terms of fire retardancy.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Wood Sampling

The wood samples for fungal decay tests, Scots pine (

Pinus sylvestris L.) and beech (

Fagus sylvatica L.), were utilized for brown and white rot fungi, respectively. Both had dimensions of 50.0 (L) × 25.0 (R) × 15.0 (T) mm

3. The chosen samples did not have any defects (such as knots and resin pockets) and had standard distribution of rings, as indicated by CEN EN 113-1: 2020 [

26].

The cross-sections were sealed with a bi-component resin, supplied by Renner SpA, Italy.

The sealing resin was applied before being put in contact with the fungi, to avoid the introduction of fungal hyphae in the preferential direction (the axial direction of the wood), and to simulate a more realistic situation, where the wood preservatives in a wooden element principally enter from tangential and radial directions.

Mini-blocks, 30.0 (L) × 10.0 (R) × 5.0 (T) mm3 of Scots pine, (Pinus sylvestris L.) were used for the flame retardant treatments.

2.2. Determination of Laccase Activity

Dilutions of laccase Novozymes© 51003 were prepared in phosphate buffer solution (1.0 mM, pH 7). Enzymatic activity was determined by mixing 350 μL of 2.13 mM 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS) solution and a 1ml phosphate buffer solution (0.1 M pH 7) with 150 μL of laccase dilution in a plastic spectrophotometer cuvette at room temperature.

Blank was prepared by mixing 1.15 mL of phosphate buffer 0.1 M solution and 350 μL of 2.13 mM ABTS solution. The change in color was followed by absorbance (ABS) at 420 nm over 30 s (since the addition of laccase to the preparation mix). Data were fitted to a linear model and the slope (∂ABS/∂min) was transformed to enzymatic units (U) with Beer–Lambert law, using 36,000 L/mol.cm as the molar extinction coefficient and 1 cm as the cuvette’s length. U (1 μmol min−1) is defined as the amount of enzymes needed to oxidize 1μmol of substrate in a minutes

2.3. Treatment against Fungal Decay

Kraft lignin (KL) was previously obtained from the black liquor of a

Eucalyptus globulus Kraft cooking mill (Ence, Pontevedra, Spain), as reported by Fernández-Costas et al., 2017 [

27,

28] and other authors [

29]. Sulfonated lignin (SL) was provided directly by Renner. Furthermore, a trademark Renner SpA, Italy commercial product was utilized.

For each product, 12 replicates of Scots pine and beech were immersed inside in a 5g/L treatment solution (KL or SL) and, when applicable, 100 ppm of AgNPs (TNS NpAg_925 ETG 10,000 ppm) in a wood–solution ratio of 1:4 (v/v) for 30 min. Then, laccase was added to reach a concentration of 10 U/mL in the final solution. Finally, incubation was carried out with shacking at rpm 75 for 2 h at 50 °C.

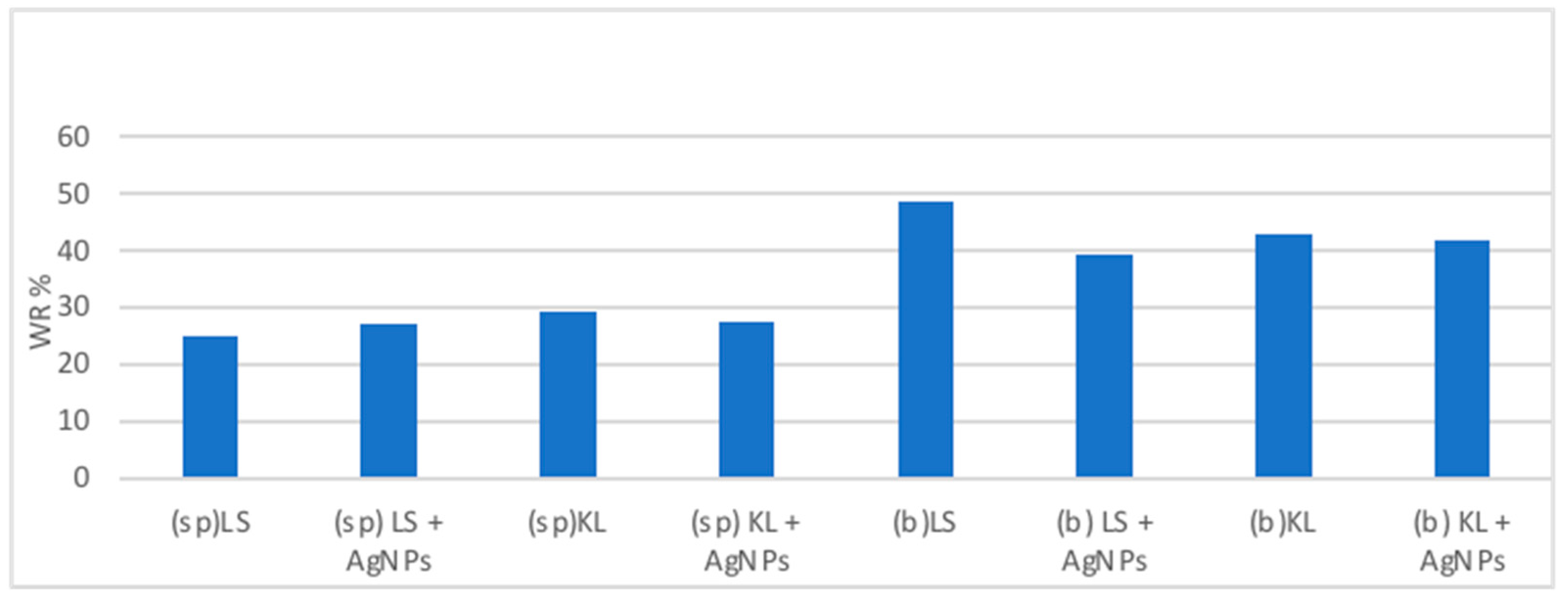

The percentage weight of the retained solution (WR) is

After incubation of the wood samples and conditioning them until constant weight, six replicates of Scots pine and beech, respectively, were put in contact with fungi Coniophora puteana (Schumacher ex Fries) Karsten, strain BAM Ebw. 15, Federal Institute for Research and Materials Testing, German, and Trametes versicolor (Linnaeus ex Fries) Pile strain CTB 863 A, Institut Technologique FCBA–Laboratoire de Biologie—Allée de Boutaut—BP 227. The duration of the biological test was 16 weeks at 22 ± 2 °C and 75 ± 5% RH.

Six impregnated replicates of Scots pine and beech, respectively, underwent a leaching procedure, in accordance with CEN EN 84 [

30]. The procedure of leaching consisted of impregnation with bi-distilled water (cycle: vacuum 40 mmHg for 20 min and 2 h at atmospheric pressure) and, after this, the samples were continually immersed in water for a period of 14 days. During this period, nine changes of water were effectuated. At the end, the specimens were conditioned at 65%RH (relative humidity) and 20 °C until constant weight, and then sterilized with autoclave before put in contact with fungi.

Through this procedure, it is possible to evaluate the wash out of impregnating product from the wood. In other words, it allows for the evaluation of the fixation of KL, SL and AgNPs in the different treatments.

After 16 weeks, the samples in contact with fungi in a climatic room (22 ± 2 °C, 70 ± 5% RH) were cleaned from mycelia and weighed to determine the Moisture Content percentage (MC%), then dried at 103 °C for 24 h and weighed again to determine the mass loss percentage (ML%). The formulae are reported below:

where

mwf: final wet weight and

mdf: final dry weight

where

mdi: initial dry weight and

mdf: final dry weight

2.4. Impregnation of Mini-Blocks with Flame Retardants

A solution of TBBPA (Sigma Aldrich, Madrid, Spain) in a water–acetone solution (3:1; v/v) with the pH adjusted to 8.0 was prepared. All mini-blocks were dried for 24 h at 105 °C and then cooled down for 2 h in a desiccator before being weighed. Prior to the treatments, the blocks were conditioned at 22 °C and 65% RH until constant weight.

The impregnation of blocks was performed in a 100mL glass Schott bottle with a cap and two inlets for the vacuum and solution line, respectively. The wood pieces were placed inside and ballasted to avoid flotation of the pieces in the solution. A volumetric ratio of 1:2 wood–treatment solution was established for this assay (15 mini-blocks in 45 mL of solution). First, wood pieces were subjected to 35 min in the vacuum (100 mbar) to displace the air in the pores and create negative pressure. Then, the vacuum line was closed and the treatment solution was allowed to flow inside the bottle, avoiding any air input in the bottle. Then, the vacuum line was opened and held for 10 min at a level of 250–300 mbar, preventing acetone from evaporating and the precipitation of TBBPA. Finally, lines were opened, creating a differential pressure, which forces the entry of the solution into the wood pieces.

After impregnation, the bottle with the mini-blocks and solution was pre-acclimated at 50 °C in a laboratory water bath for 15 min. Then, the bottle was placed in an orbital shaker at 50 °C and 75 rpm. Laccase was added at a large enough volume to achieve a relation with 50 U/g dry wood. Incubation was performed in these conditions for 2 h. The bottle was left without its cap, because the diffusion of O2 into the solution is desirable, since O2 is the laccase co-factor.

Once the 2 h of enzymatic treatment was finished, mini-blocks were weighed and the weight retained percentage (WR%) was calculated. Mini-blocks with deviations of 10% from the mean were rejected to characterize the treatment. Mini-blocks were dried at room temperature for 24 h.

Three treatments and a control were performed with the same procedure:

Treated mini-blocks were washed with a solution–wood ratio of 5:1 (v/v). Three mini-blocks (≈4.5 mL) were put into a Falcon tube with 22.5 mL of washing solution water–acetone (1:1). Falcon tubes were placed in a rotating agitator for 1 h and, finally, mini-blocks were superficially washed with distilled water three times. Pieces were let dry at room temperature 24 h.

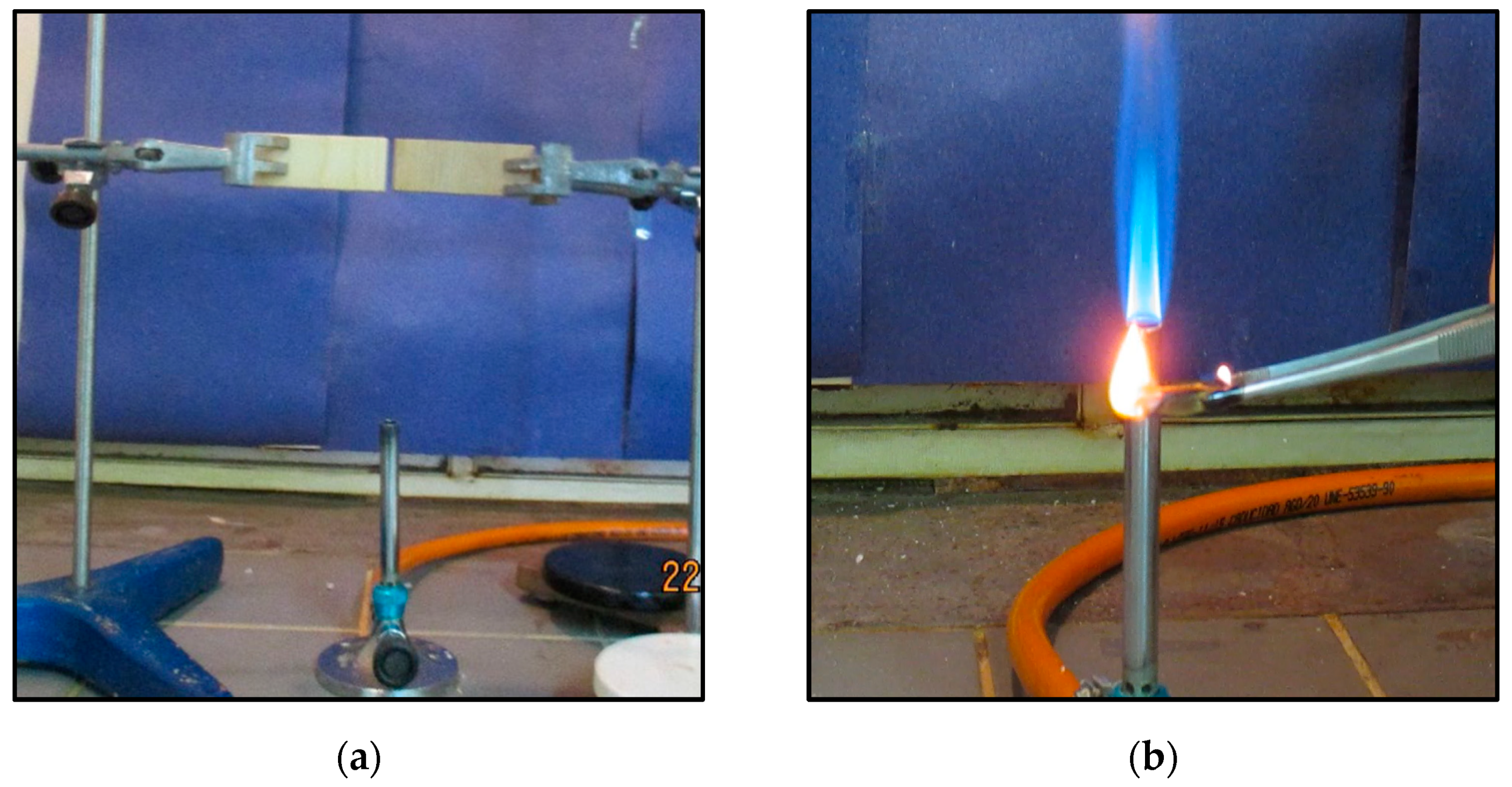

The flame retardant assay was set up using two laboratory stands with corresponding iron clamps where the mini-blocks were held at a height of 13.5 cm to meet the top of the Bunsen burner. Two pieces were tested at the same time in order to evaluate the differences between the control and a treated sample. Flames were burning for 1 min. Propagation was observed for 30 s, and then this process was repeated one more time. Lastly, 3 min of flame was applied and the wood pieces were weighed to determinate the mass loss (

Figure 1a). Alternatively, a new assembly was proposed (

Figure 1b). In this assembly, individual wood pieces were put into the Bunsen flame for 8 s and then the flame propagation time was recorded. This step was carried out three times. At the end, burned wood pieces were weighed and loss mass percentage was calculated.

4. Discussion

The absorption of the treatment solution in the wooden mini-blocks was species dependent.

F. sylvatica has higher values of absorption than P. sylvestris. Some wood properties, such as texture, density and porosity, may affect the retention values. Moreover, the differences between hardwood and softwood can explain such differences: the diameter of vascular cells in softwoods is in a range of 15–60 μm; meanwhile, for hardwoods, it is 75–200 μm.

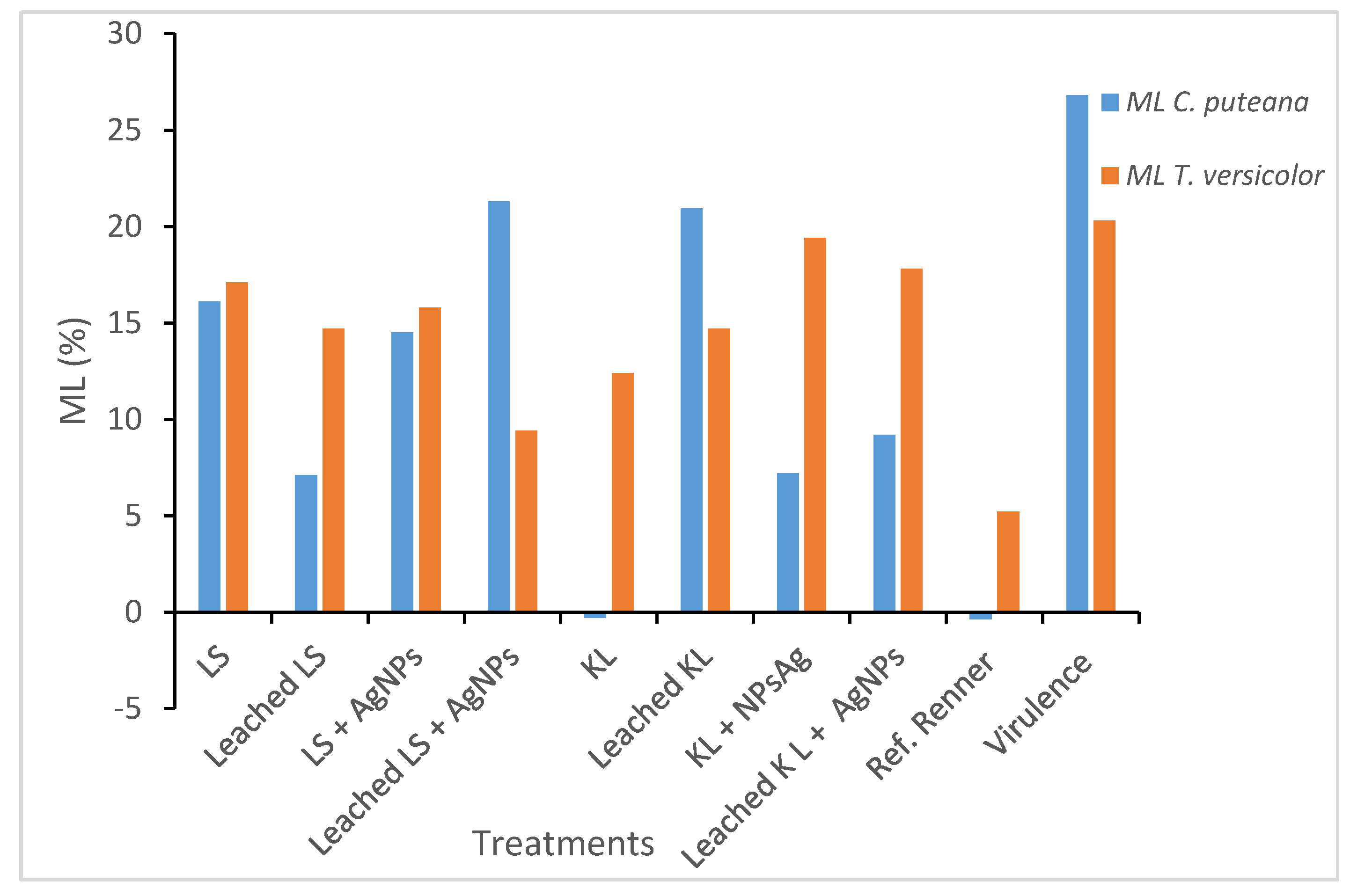

The KL treatment showed a good resistance against both fungi when it was applied alone (without silver nanoparticles for

C. puteana). In fact, the performance of KL was close to that of the commercial product that was tested. The presence of nano-silver seems to improve resistance against

C. puteana, even after the leaching procedure. These results regarding KL alone or with AgNPs exceed the aspects of previous tests carried out with agar plates [

27]. Nevertheless, the previous studies carried out using impregnated wood with different types of lignins provided promising results regarding increased effectiveness against fungal decay [

30].

KL polymerization in the presence of silver nanoparticles could retain such nanoparticles during the leaching process, since this polymerization process may entrap them. This hypothesis has been previously proposed to explain the reduced leaching of copper observed in similar treatments [

27]. This entrapment is an important advantage of the in situ polymerization process produced during the treatment, since the silver nanoparticles could be retained for a long time. Unfortunately, resistance against

T. versicolor showed lower biological resistance, both with and without silver nanoparticles.

LS and LS AgNPs treatments showed low efficacy against both fungi; the only positive result obtained with LS was with

C. puteana and the leached samples. The presence of AgNPs was not useful for improving resistance against either fungi. The leaching procedure seemed to improve effectiveness, both against

C. puteana and

T. versicolor. In this case, it is difficult to find a scientific explanation. It is important to keep in mind that the objective of combining AgNPs with LS or KL is to limit the leaching of AgNPs (as was already demonstrated for other preservatives [

24]); however, secondary, and undesirable, effects could be produced. These effects may influence the AgNPs availability to the fungus and, therefore, limit their performance in durability improvement. When LS or KL is added, together with laccase, and applied to wood, LS and KL may produce larger polymers by copolymerization. This means they can graft onto the wood surface, producing, at the end, a complex matrix on the wood surface. When this process happens in the presence of AgNPs, this matrix can include nanoparticles. The interaction of nanoparticles with KL or LS, which depends on the structure and functionality of LS and KL, as well as the operational conditions of the treatment (enzyme dose, pH, treatment time, temperature, etc.) may affect the level of fixation of AgNPs into the matrix. Such interactions are very important to elucidate the real effects of nanoparticles in combination with LS and KL, although they are not the objective of this work. Depending on the level of fixation, the AgNPs could be ready to act against fungi or they could be completely entrapped and not readily available, at least for some time. In the latter case, a leaching process could improve the availability of AgNPs and, therefore, improve durability, in comparison to non-leached samples. However, this effect is not as important for real-world application, since the effect of nanoparticles is expected to be produced in the same way and observed sometime after fungal colonization. In the case of KL and AgNPs, the improvement in AgNPs was observed without leaching, which denotes that that LS and KL form different matrices that can act differently against fungi.

The reference product supplied from Renner resulted as efficient, in accordance to EN 113, against C. puteana and with a mass loss of slightly more than 3% against only T. versicolor. In both cases, it was suitable at the utilized retentions and was applied for immersion after sealing the end grains for use in class 3.

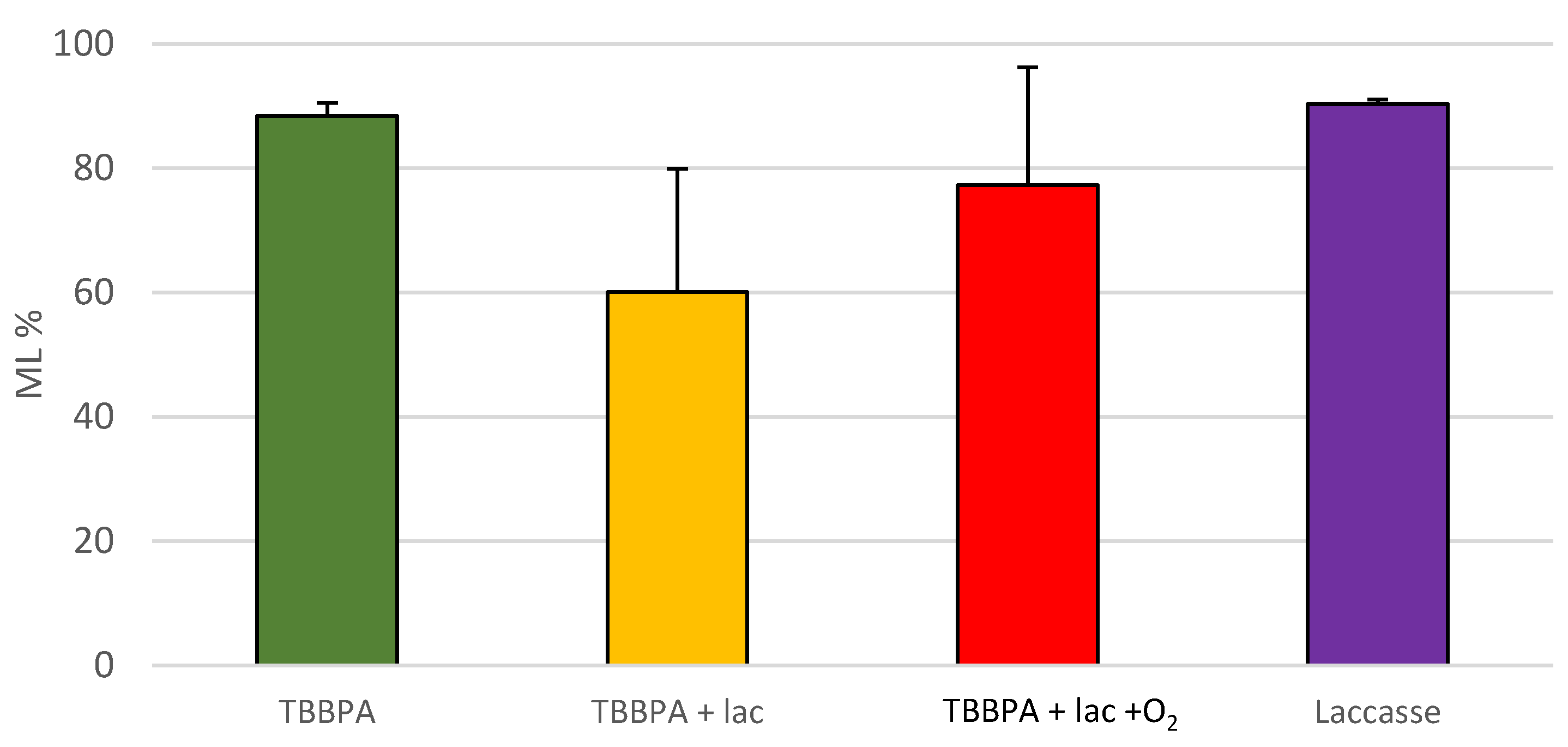

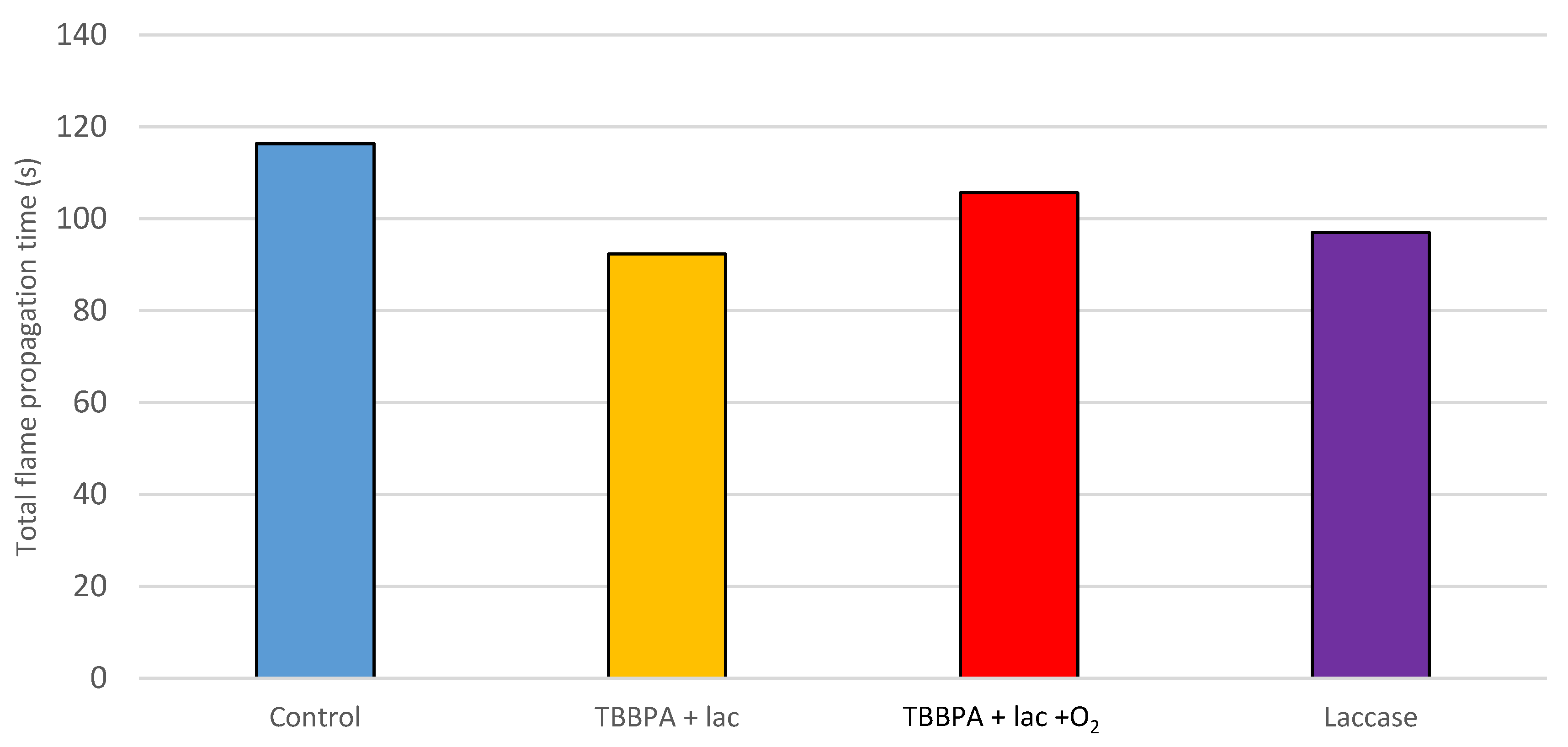

Regarding the grafting of TBBPA, no clear effects were observed. The treatment of TBBPA with laccase improves the results of TBBPA alone. Considering the washing procedure that was performed after the treatments, this result suggests an effective fixation of TBBPA that was able to slightly improve the wood’s behavior against fire. However, the rest of the control experiments produced some positive effects as well, meaning the results are not conclusive and do not demonstrate a positive effect of grafting on flame retardancy.

An increased fixation of TBBPA to the wood surface is reached, as

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 show. TBBPA assisted by laccase had the shortest flame propagation time and the lowest mass loss percentage. On the other hand, the blowing of oxygen did not result in the expected improved effect.

Moreover, considering the trend of phasing out bromine flame retardants in Europe, the recommendation of TBBPA grafting should not be made. Furthermore, bromide flame retardants are restricted more and more by the European Union and they have been voluntarily phased out in the USA [

31].

5. Conclusions

In this article, two objectives were pursued: the evaluation of grafted KL and LS, with or without silver nanoparticles, for wood preservation; the grafting of TBBPA on wood surface in order to increase the fixation of this flame retardant to the wood.

The grafting of KL and LS on the wood surface, assisted by laccase, showed an increased biological resistance against fungi C. puteana and T. versicolor, even after a leaching procedure, compared with an untreated control. These results, despite not reaching the same performance of the product reference used in the study, are very promising. In fact, it could represent a green solution for wood preservative purposes. The addition of silver nanoparticles did not improve efficacy in all the cases.

The efficacy of TBBPA as a flame retardant is not clearly improved by the utilization of laccase for grafting.