Abstract

Community Forest Governance is a process of building agreements and decision-making about rules and norms for the use and access to forest resources of common use. The main objective of this study was to know the level of governance about the management and conservation of the forest of the agrarian community of San Miguel Topilejo, in Southern Mexico City. A survey was applied to a representative sample of 58 community members. The level of governance is determined by a composed indicator that includes criteria and specific indicators of social capital, collective action, and local organization. The main finding shows that social capital is low because there is little cohesion between community members. Community collective action shows a lack of cooperation and coordination to enforce norms and sanctions in the use of forest resources. The level of organization is low because the structure of positions and roles is very basic and not specialized. The conclusion is that the level of governance is low because this community has no clear common objectives, there is a lack of well-established norms and sanctions, and there is a lack of involvement of owners in the decision-making process and management of forest resources of common use.

1. Introduction

The dynamics of forest cover in Mexico is characterized for continuous deforestation caused by the expansion of the agricultural or urban frontiers [1]. The tropical and temperate forests are important sources of employment and income for the population living within or near woodlands. Deterioration of forest resource governance makes more attractive the land use for agriculture or extensive grassing of livestock than the land use for forests.

This study defines forest resource governance as the social process to arrange agreements among social, economic, and government stakeholders to regulate the use, access, management, and conservation of forest resources by establishing common objectives, rules and norms, rights and duties of owners, ways of participatory decision-making processes, forms of distribution of benefits, responsibilities of labors, roles and work positions, forms of accountability. The agreements can be written or verbal, but all stakeholders must honor and respect. Governance is even more important when forest land is communal property.

In Mexico, public policies have not invested enough resources in infrastructure, research, and forest development to make sustainability attractive, which means to promote use and conservation of forests at the same time. Logging is a productive activity that has relatively high costs and low profits in a short time. It makes that rural people may think that it is better to change the forest land use for extensive agricultural uses [2].

Lack of forest governance and the limited institutional development in Mexican forest lands have been causes of deforestation because they have stimulated conflicts in land uses within and among forest communities. The low institutional development does not allow to solve problems like illegal logging, prevention and control of fires, and promotion of sustainable forest management. Since the end of the twenty century, Mexico had a reduction of 50% of the original natural vegetation. Between 2010 and 2015, the rate of deforestation was estimated at 91,712 hectares per year, considering only temperate and rain forests [3].

In Mexico, at least 60% of temperate and rain forests were communal property belonging to agrarian communities and ejidos-agrarian communities have communal property on their land, even when they may have divided the land for individual use. The property land titles were granted by the King of Spain during the colonial period; Ejidos are similar to agrarian communities, but they were created after the Mexican Revolution (1910–1917) and also have communal property of land. The Mexican federal government issued the Ejido property land titles during the agrarian reform (1917–1991). The land of ejidos and agrarian communities can be used but not to be sold unless more than 70% of their members vote in an assembly to change the property from communal to private. San Miguel Topilejo, our case of study, is an agrarian community) and all the wooden and non-wooden resources and Common Use Resources (CUR). Many ejidos and agrarian communities have preserved their cultural identity and social organization despite external pressures to make changes in their organization and ways of life and production. They have traditional strategies of using natural resources to warrant their subsistence.

Their organization and strategies, based on informal norms and local customs, shaped community governance of their natural resources for centuries. One characteristic of community governance is the co-responsibility between stakeholders that emerged for the need to solve collective problems [4,5]. Theoretically, most of the communities have different degrees of governance by the definitions of roles, arrangement of agreements, definition of rights, sanctions, and responsibilities, decision-making processes, and mechanisms of resolving conflicts. This process is a relation of political power between community members, who have rights of use and access to forest resources [4].

A very important element of community governance is how community members establish a decision-making process based on their own objectives to use their community resources (human capital, social capital, natural resources, infrastructure, and financial assets) taking into account external and internal restrictions [6] and the external social networks they have built.

Public policies for deforestation and forest degradation should understand the logic of forest owners when they define strategies for decision-making process about the current land use and the tendency of changes of land use from access and restrictions in the use of land [1,7].

This study assumes that the deforestation and forest degradation of the CUR have external and internal causes in the agrarian community of San Miguel Topilejo, Mexico City. In this context, the main objective was to know the level of community forest governance in the use, access, management, and conservations of forest resources by constructing a composed indicator of governance, therefore, we need to answer the following questions: Is the community able to build appropriate mechanisms to build governance? How external factors restrict the community forest governance?

Background

Mexico has great forest potential but suffers a continuous process of deforestation and forest degradation. Currently, deforestation is more common in rain forests than temperate forests, mainly in areas that are not under silviculture management, while forests in high mountains are affected by degradation. In both cases, the dynamic of soil use follows a tendency in favor of the expansion of extensive agriculture and grassing against forest areas. The lack of economic resources drives owners to use the forest in an unsustainable way that has impacted negatively natural ecosystems, and they have no capital to improve their current productive systems [8,9,10].

Current strategies of conservation of forest resources in Mexico are centered on subsidies and support activities of passive conservation with little or null human intervention. Passive conservation promotes activities like monitoring of vegetation and surveillance of the use of forest resources, building of firewalls, collect dry vegetation, reforestation among others. However, passive conservation prohibits the use of most forest resources for commercial purposes. It happens in Mexico City since 1947 when federal governments issued a ban to prohibit logging within the city, under the argument that it was going to conserve the forest resources for ecosystem services. This is because it is an easy way for government policies to promote conservation. However, in recent years, it has been demonstrated that dynamic conservation is a better way to conserve forest resources, it means conservation by using forest resources but, at the same time, taking care of their conservation. The problem is that it must be based on effective governance with the active participation and organization of owners of the forest resources through committees and task force groups for logging, monitoring, conservation, and administration of economic and social resources. Those committees should establish participatory decision-making to build consensus [11,12] and make development inclusive.

Forests tend to a gradual degradation under passive conservation. When active conservation is applied in a good way, it does not allow forest degradation. On the contrary, dynamic conservation has to create mechanisms to improve quality and quantity of forest resources because owners depend on healthy forests to improve their own wellbeing. But, it happens only if owners are willing to participate and be part of it. When they are waiting for the government to solve their problems, either dynamic or passive conservation does not achieve good results.

Conservation is an efficient operative process when conservation task groups are instruments that link stakeholders within a territory to propose socially feasible strategies to protect ecosystem services. Participation of community members in the management of forest resources is an essential indicator of active conservation, to integrate within a territory different productive activities in a stable way [13].

In Mexico City, participation of agrarian communities and ejidos is focused on the creation of Community Areas of Ecological Conservation and Community Ecological Reserves to do forest protection and conservation and develop technical capacities to do those activities through community brigades and surveillance committees [1,5,14].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of Study Area

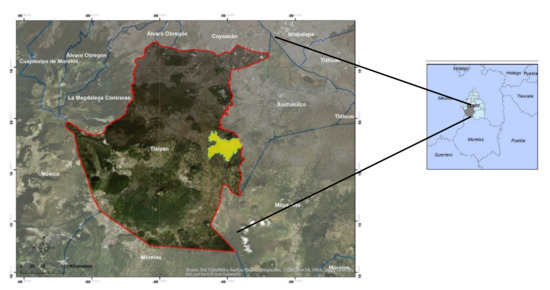

The Figure 1 shows the location of the agrarian community of San Miguel Topilejo is a village located in Southern Mexico City.

Figure 1.

Research site was San Miguel Topilejo. Source: Elaborated by Magos-Hernández in 2019 with information from INEGI [15].

Land tenure in San Miguel Topilejo had a non-common duality because this village had ejido land and agrarian community land. Forest lands are under community land tenure and agricultural, grassing, and urban lands are under ejido land tenure. Agrarian community lands are 10,354 hectares, 6000 of those land are part of the Community Ecological Reserve. These lands have only conservation activities with no logging management.

The agrarian community has 446 members. Most of them are working outside of the community in the services sector (61.75%), some of them in the industrial sector (26.89%), and a few of them in primary activities (agriculture, livestock, and forestry) (11.36%) [16].

2.2. Techniques of Data Collection

A survey was applied to a representative sample of 58 community members with land tenure titles. This information was complemented with semi-structured interviews and direct observation during different community processes like assemblies, meetings, and fieldwork.

2.3. Sampling

We use a maximum variance formula to calculate the size of the sample (Equation (1)). We stated the level of confidence at 90% and sample error at 10%.

where:

- n = simple size = 58

- N = community population = 416

- p = proportion of population with a binomial characteristic = 0.5

- q = 1 − p = 0.5

- Z = value of normal distribution (Zα/2) at 90% of confidence = 1.64

- d2 = precision at 10% = 0.1

2.4. Conceptual Design

We design a composed indicator to measure the level of community forest governance of use, access, management, and conservation.

A composed indicator is a simplified representation of a multidimensional concept by a simple index (unidimensional), based on a conceptual model, which can be qualitative or quantitative. The main characteristic of the composed indicator is to resume numerous aspects in one value [17].

The composed indicator integrates three criteria: social capital, collective action, and local organization. Optimum percent values are assig to each criterion according to its importance and the sum of their values is equal to 100% (Table 1).

Table 1.

General criteria and optimum values of the composed indicator of community forest governance.

Every criterion is broken down into specific indicators. We weight every indicator and assign optimum percentage values to each indicator. The sum of percentage values is equal to 100%.

Every optimum value of general criteria was converted into 100 to assign percentage weight to each specific indicator (Table 2), e.g., the 25 points of social capital were converted into 100 and divided among the 6 specific indicators.

Table 2.

Criteria and specific indicators to measure the level of community forest governance.

Every specific indicator is disaggregated into variables. Each variable is qualified with an ordinal scale that is transformed into a numeric scale (null = 0, very low = 1, low = 2, medium = 3, high = 4, and very high = 5). All variables were statistically processed, each statistical result was converted into the ordinal scale, and then, into a numerical scale. Later, we summed all values to obtain the percentage value of each specific indicator and every criterion to determine the level of community forest governance in San Miguel Topilejo (Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5).

Table 3.

Specific indicators and variables of social capital.

Table 4.

Specific indicators and variables of collective action.

Table 5.

Specific indicators and variables of the local organization.

Finally, we define four sceneries or levels of governance in Table 6 to qualify the results of research based on the theoretical framework from which we selected criteria, specific indicators, and variables to build the composed indicator of community forest governance.

Table 6.

Definitions of levels of community forest governance.

3. Results

The level of community forest governance is determined through a composed indicator that integrates three criteria: social capital, collective action, and local organization for forest management and conservation.

3.1. Social Capital

Social capital is formed by relationships of trust and reciprocity that allow collective action and community organization [18]. Relationships of trust, reciprocity, and cooperation become benefits for the community because they generate cognitive ties from experiences between forms of how to relate socially and how to learn within a community [19]. Some aspects of social capital have been created in the daily living of community members, however, these aspects are not enough to develop a way of working for forest management and conservation. Other aspects can be developed only through training and the organization of human capital. At this point, it is necessary to remember Fukuyama’s definition of social capital [20], which states that social capital is composed of shared norms and values that allow people to cooperate and work together to achieve common objectives. It means that social capital is attained to people but it can be expressed only when people work together with others. This is the difference between human capital that is attained to a person. Human and social capital are important as the basis of community forest governance.

Social capital criterion includes concepts as transparency, trust, legitimacy, reciprocity, co-responsibility, and solidarity. The current social capital of the agrarian community of San Miguel Topilejo is low (38%). Despite this level of governance, the community is doing conservation activities because of the commitments with government institutions from which they receive economic and technical support. The benefits from that support are low but community members have a sense of belonging and identity with their forest lands, which motivates them to continue processes of forest conservation.

In Table 7, we estimate the real values of each specific indicator compared with the optimum value. Most of the real values are low.

Table 7.

Evaluation of specific indicators of social capital as part of community forest governance at San Miguel Topilejo.

3.1.1. Transparency

In this specific indicator, we pay attention to information about conservation activities and leaders’ accountability, but also the way of ideas exchange between leaders and community members. In San Miguel Topilejo, 64% of community members pointed out that accountability is given during assemblies and 19% of them do not know anything about accountability or 17% of them reported that information is partial and discontinues. Most community members underline that sometimes community has bad administration of economic resources, and there is no availability of administrative information (48%).

According to Merino-Pérez and Martínez [5], accountability is very important in forest communities to generate processes of trust and collective action to conduct good forest management. In San Miguel, it does not happen. On one side, leaders decide how to manage economic resources with no participation of community members, on the other side, community members do not have too much interest in knowing how economic resources are managed because there have few benefits or their productive activities are outside the village.

3.1.2. Trust

Trust among community members reinforces processes of credibility, legitimacy, reciprocity, and co-responsibility to arrange agreements that allow conservation activities. In this community, only half of the community members (52%) have confidence in leaders and the veracity of information and are confident (59%) to express their opinion in meetings or assemblies. Some women pointed out that male chauvinism prevails among community members (women and men), when they speak out on assemblies, they are called despicable names. The atmosphere in assemblies normally is against divergent opinions, sometimes leaders or other community members are not willing to hear differing opinions.

Trust and credibility are a result of long processes of stakeholder interaction discussing how to get better harmony in community relationships, showing education, respect, and tolerance [21]. Processes of getting trust in each other are difficult to create when active participation is not fostered in communities.

3.1.3. Legitimacy

Legitimacy is referred to how the decision-making is done, if only leaders take decisions or if community members are involved actively in those decisions. The only way of participation for community members is within assemblies. Leaders propose the agenda in assemblies, inform about the topic of the agenda, and establish the terms of discussion. The agenda is not generally open to other topics proposed by community members. Community members can participate in discussing topics in a limited manner, their participation is reduced to voting for topics proposed by leaders.

Most of the sanctions for illegal uses of forest resources are applied by leaders. Most community members do not know how enforcement is exerted and the type of sanctions are applied for illegal uses. There are constant rumors that illegal uses happen like illegal logging, poaching, extraction of forest dirt, and other illegal uses for external people with no rights to forest resource access.

One problem is community members do not actively participate in management or conservation activities because they have their economic interests outside the village or they are too old. Community members delegate those organizational responsibilities to leaders and surveillance committees.

3.1.4. Reciprocity

The main responsibility of community members in forest management and conservation is to vote on different aspects in assemblies that leaders proposed. Most of them vote with not enough information and with little interest in the results of the decision-making.

Community members acknowledge the benefits they receive because all of them are owners of community forests, but they know that those benefits depend on how leaders administer and distribute those benefits. At the end of a year, community members receive some money for some commercial activities or economic benefits received from public programs. Other benefits can be economic support for medical expenses or the death of a family member, but it depends on if administrators have economic resources in community coffers. Another benefit is to get a job in the forest conservation brigade. Sometimes, leaders define how to distribute jobs among community members, but if one of those has a right for a job, this person can give the job to a family member. For these reasons, most of the conservation brigades are integrated by relatives.

3.1.5. Co-Responsibility

This specific indicator is referred to assign and delegate responsibilities among leaders and community members. The main responsibility of community members is to assist and vote in assemblies. It means that they have little responsibility in forest conservation and management because they delegate this responsibility to leaders.

Forest conservation brigades are in charge of operative managers, who generally are community members.

Sometimes leaders of government institutions ask for some communal task to benefit all the community, like maintenance of roads, firefighting, or other another task. All community members must participate, if they do not participate they have to pay somebody else to do their job assignment.

Again, community members do not participate in forest conservation because of their main outside job or they are too old to do these jobs.

3.1.6. Solidarity

Community solidarity is the support of community members to each other in case of emergencies. When an emergency occurs in the forests, there is little participation of community members. This task is done by forest conservation brigades and government brigades. When an individual emergency happens, individuals help only if there is an affinity between community members. There is no obligation to help each other.

3.2. Collective Action

Collective action is mostly the result of cooperation and coordination among internal stakeholders with the support of external stakeholders to achieve common objectives that let the decision-making process be transformed into action. It is possible through an organization based on formal and informal norms, enforcement of rules, mechanisms of sanctions, and social controllership. Collective action is viable when there is a community atmosphere of trust, transparency, legitimacy, co-responsibility, reciprocity, and cooperation [5].

In San Miguel Topilejo, the collective action indicator is at a low level (40%) (Table 8). The community does not have autonomy for the decision-making process or establishing rules for the use, access, management, and conservation of forests. There are two reasons for that situation: (1) A forest management ban issued in 1947 by Mexico City government that reduces forest management to forest conservation activities and prohibits logging; (2) there is no active participation of community members in forest conservation and management. It means, there is little room for the community to define rules and norms of how to use and access their own forest resources. The only economic resources available for forest conservation come from public programs which are applied to activities defined by government institutions.

Table 8.

Evaluation of specific indicators of collective action as part of community forest governance at San Miguel Topilejo.

3.2.1. Formal and Informal Norms

The agrarian community of San Miguel Topilejo has no internal regulation, which means that work relationships for forest conservation and management are not regulated. Sanchez-Vidaña [22] mentions that regulations are important to manage forest use and conservation in a good manner. Regulation is a central axis for community governance.

Community members define agreements and decision-making only in community assemblies through their vote but also delegate responsibilities of forest management to leaders. Leaders are responsible of execute activities of conservation.

Most of the norms are informal, they are the result of traditional relationships. When rules and norms are not written, it makes difficult that community members can demand leaders the fulfillment of their responsibilities.

Prohibition of the use of forest resources does not come from internal rules. The Mexico City government issued a legal ban on the use of wooden forest resources and limited the use of non-wood resources. Leaders and community members only are responsible for the ban enforcement. The ban only allows one to do conservation activities in forest soils. Community members only can decide how to use economic resources that are granted by government institutions for conservation.

Leaders and heads of brigades are responsible for the operation of conservation. They also do the planning, management, monitoring, verification, and conflict resolution internally. Externally, they negotiate support and resources with government institutions.

3.2.2. Enforcement of Rules and Norms

Most of the community members know which actions are prohibited and are willing to follow the norms, for example, illegal logging, poaching, extraction of forest dirt, and obviously forest wood. City and federal governments define which products can be extracted or cannot be extracted. The extraction of non-wood resources (mushrooms, mosses, medicine plants, etc.) needs a permit issued by community representatives. Permits are obligatory for external people, but sometimes community members do not need a permit if they extract little quantities for personal or family use.

3.2.3. Mechanisms of Sanctions

Most of the community members (91%) know the rules and assembly agreements about rules and prohibitions to use forest resources, however, they do not know sanctions and how sanctions are enforced because community representatives do not inform about them.

Some persons (41%) pointed out that the most common sanction is a public reprimand for community members when they break rules of extraction. When external people break the rules, brigades and representatives give a reprimand (29%) or call the police or other authority to impose a legal or punitive sanction (14%). The problem is that sometimes authorities do not act legally against those persons. Some brigades mention that they are not prepared and equipped to face wrongdoers. Sometimes wrongdoers use a gun or other weapons, in those cases brigades cannot act against those people. Most of the illegal extractions take place at night.

3.2.4. Schemes of Social Controllership

Leaders are responsible for the administration, planning, registry, and control of conservation activities. Most community members do not exactly know what actions representatives and brigades are doing and they have little access to registry information.

Social controllership demands the active participation of stakeholders in decision-making but also in supervision or evaluation of representatives’ responsibilities and activities. Community members’ participation in surveillance and monitoring reinforces collective action and local organization.

In the past, representatives invited community members to supervise brigades’ work at the field level, but that has been reduced in recent years because of the lack of community members’ interest. Participation in assemblies and the supervision of brigades were the only mechanisms of controllership.

3.3. Local Organization

The form of organization of a community to forest conservation and management defines how successful can be. The organization should be the result of the functionality of the construction of agreement and decision-making processes. Organizations improve when forest management is active, when forest management is passive or incipient, organization may not be adequate to get common objectives, as it happens in San Miguel Topilejo.

The level of a local organization is relatively low (49%) (Table 9).

Table 9.

Evaluation of specific indicators of local organization as part of community forest governance at San Miguel Topilejo.

3.3.1. Structure of Communal Administrative Representation

The structures of roles and positions in San Miguel Topilejo are is the structure permitted by the federal agrarian law (Community members’ assembly, board of representatives, and the surveillance committee). The same law also defines the functioning of these structures. At the interior of the community, the only structure created is the forest conservation brigade. It means that there is no structure created for the community’s needs.

As we stated before, the board of representatives are in charge of planning, operation, surveillance, monitoring, enforcement of norms, management, and operation of forest conservation activities. The assembly is the forum to discuss objectives, sanctions, rules, and other necessary aspects to maintain working in the community.

The board of representatives works mostly to respond to government programs that provide economic support for forest conservation. The prevailing opinion among community members about the performance of organizational structures is not as good as it should be, according to 48% of the community members.

3.3.2. Community Members’ Participation in Assemblies

Community assemblies take place every three months, but sometimes this time period changes according to the importance of the topic.

The participation of community members is low. Half of them (52%) rarely express a verbal opinion in assemblies, and only 43% of them believe that their opinion is considered for decision-making.

3.3.3. Topics in Assemblies

Representatives propose the topics discussed in assemblies, little topics are proposed by community members. According to community members, representatives do not give enough information and provoke confusion, especially when conflicts occur (69%). The most recurrent topics are internal problems among community members, conservation activities, and negotiation of government support for forest conservation.

3.3.4. Ways to Get Agreements and Decision Making

Building consensus among community members should be a requirement for adequate forest conservation and management. When communities do not achieve consensus, indiscriminate use of forest resources can be fostered [23]. The only way to get agreements is the vote for community members in assemblies. Monitoring of agreements is representatives’ responsibility without members’ participation.

Generally, community members have little information to arrange agreements, but they follow the leaders’ recommendations. Members are little interest in agreements and decision-making because they cannot influence those processes and their interests are in economic activities outside of the village.

3.3.5. Conflicts

Conflicts are very frequent in most forest communities in Mexico City because many social, political, and economic pressures come from internal and external sources. Some of the internal conflicts come out from the lack of fulfillment of responsibilities, lack of interest of community members to do conservation activities or communal tasks, and bad communication between the board of representatives and community members.

The first entity that deals with conflict is the board of representatives. When representatives do not solve conflicts, they are treated at the community assembly. There are no systemic directions or norms to solve conflicts, the solution comes from a casuistic way. If problems emerge in the operation of conservation tasks, the person in charge of brigades tries to solve those conflicts in coordination with governmental technicians. Conflicts about rights of land tenure are solved by the agrarian authority with some participation of community assembly.

3.3.6. External Social Networks

Ejidos and agrarian communities need support from the government, NGOs, and other social organizations to implement actions related to social capital, collective action, and local organization for forest management. San Miguel Topilejo has received support from the local, city, and federal government, academic institutions, NGOs, and other external social actors. The board of representatives interacts with external actors with little or null participation of community members.

The major support comes from the Commission of Natural Resource of the Mexico City Government (CORENA for its name in Spanish), through a Program for Community Areas of Ecological Conservation. This program provides the economic support for paying to community conservations brigades, which currently has about 66 members.

3.3.7. Definition of Roles

The definition of roles in San Miguel Topilejo is influenced mainly by external situations and actors. Community members have delegated the most important responsibilities to the board of representatives. The main role of most community members is been a voter in assemblies, however, as we described before, assemblies are manipulated by leaders to get the support of most members to their proposals. Some of the roles and positions in the community organization structure are defined by the federal agrarian law, but the rest of the roles and positions for management and conservation are filled under the leaders’ criteria and interests.

Representatives carried out the control of conservation activities. Representatives and heads of brigades define the roles of each brigade’s members in conservation activities.

3.3.8. Distribution of Benefits

Community members get few benefits for the use of community forests because of the forest ban issued by the city government in 1947. The ban only allows owners to gather some non-timber forest products for family consumption but not for commercialization. The only benefits from the forest come from the participation in government programs for forest conservation and ecosystems services. Government programs pay the salaries of the conservation brigades. Payments for ecosystem services are distributed for conservation activities and some other resources are given in cash to community members at the end of the year. This makes that community members have little interest in forest conservation.

3.4. Level of Community Forest Governance the Agrarian Community of San Miguel Topilejo

Evaluation of the level of governance had several steps:

- Definition of three criteria: Social capital, collective action, and local organization.

- Criteria were broken down into specific indicators and variables.

- Assignation of optimum values before data collection.

- Calculation of real values after data collection and processing.

- Evaluation by comparing real values to optimum values.

- Determination of the level of governance according to real values.

The level of governance is low according to data shown in Table 10.

Table 10.

Composed indicator of community forest governance in San Miguel Topilejo.

4. Conclusions

We conclude that the level of community forest governance in San Miguel Topilejo is low because: the use and access to community forest resources is limited by a forest ban issued by city government since 1947 that prohibits extraction of wood products and reduces the extraction of non-wooden resources for family consumption but not to commercialization; there are no formal norms and rules for forest managements, informal rules are imposed by leaders and government institutions; Community members participation is reduced to vote in community assemblies for topics suggested by the board of representatives; Community members have little influence in decision making processes for forest conservation and management; community members used to supervise the work of brigade at the level of the field, but now this activity is no longer practiced; The board of representative enforce rules and conflict solutions; community members have no interest in forest conservation and management because they have little direct benefits from community forests and they have employment outside of the village; the only benefits for community members are granted by government institutions through forest conservation and ecosystem services programs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing, S.A.-M. and E.V.-P. data collection S.A.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no funding from other sources for the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and reviewed and approved by Graduate Program Committee of Rural Development Studies on 3 January 2018 (Agreement 20180103-02), and by Academic Committee of Montecillo Campus at the Colegio de Postgraduados on 24 January 2018 (Agreement CM.22/01-1118).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Before every interview, we read the following statement to involved subjects: “we ask for your help to answer voluntarily this questionnaire about the governance of forest resources. We warranty that all the information is going to be managed confidentially”.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Esteban Valtierra-Pacheco, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the support of the members and leaders of the agrarian community of San Miguel Topilejo.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chapela, F.J.; Pedraza, R.A.; Álvarez, R.; Hoyos, A.; Trejo, I.; Manuel-Núñez, J.; Rodríguez, Y.; Carrillo, K. El Estado de los bosques de México. In Estado de los Bosques de México; Chapela, F., Ed.; Consejo Civil Mexicano para la Silvicultura Sostenible: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012; pp. 28–60. [Google Scholar]

- Chapela, F.J. Escenario para el manejo forestal sostenible en México. In Estado de los Bosques de México; Chapela, F., Ed.; Consejo Civil Mexicano para la Silvicultura Sostenible: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012; pp. 6–27. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Nacional Forestal (CONAFOR). Inventario Nacional Forestal y de Suelos 2010–2015. Available online: http://187.218.230.4/OpenData/Extension_Recursos_Forestales/ (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Palomino, V.; Gasca-Zamora, B.J.; López-Pardo, G. El turismo comunitario en la Sierra Norte de Oaxaca: Perspectiva desde las instituciones y la gobernanza en territorios indígenas. Periplo Sustentable 2016, 30, 6–37. [Google Scholar]

- Merino-Pérez, L.; Martínez, A.E. A Vuelo de Pájaro. Las Condiciones de las Comunidades con Bosques Templados en México; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO): Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kragten, M.; Tomich, T.P.; Vosti, S.; Gockowki, J. Evaluating Land Use Systems from a Socio-Economic Perspective; International Centre for Research in Agroforestry, Southeast Asian Regional Research Programme: Bogor, Indonesia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alianza México REDD+. Diagnóstico Sobre Determinantes de Deforestación y Degradación Forestal en Zonas Prioritarias en el Estado de Chihuahua; Grupo Integral de Servicios Ecosistémicos Eyé Kawí, A.C.: Chihuahua, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Del Ángel-Mobarak, G. La Comisión Nacional Forestal en la Historia y el Futuro de la Política Forestal de México; Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas and Comisión Nacional Forestal: Mexico City, Mexico, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar, C.; Martínez., E.; Arriaga, L. Deforestación y fragmentación de ecosistemas: ¿Qué tan grave es el problema en México? Biodivesitas 2000, 30, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Pérez, I.; Carranza-Ortiz, G.; Nava-Cruz, Y.; Larqué-Saavedra, A. La percepción sobre la conservación de la cobertura vegetal. In Más allá del Cambio Climático: Las Dimensiones Psicosociales del Cambio Ambiental Global; Urbina-Soria, J., Ed.; Instituto Nacional de Ecología and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2006; pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Chapela-Mendoza, F.J. Conservación Activa de la Diversidad Biológica Mediante la Acción Colectiva: El caso del Proyecto COINBIO. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Iberoamericana Puebla, Cholula, Mexico, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Madrid-Ramírez, L. Los pagos por servicios hidrológicos: Más allá de la conservación pasiva de los bosques. Investig. Ambiental. 2011, 3, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Troitiño-Vinuesa, M. Espacios naturales protegidos y desarrollo rural: Una relación territorial conflictiva. Boletín Asociación Geógrafos Españoles 1995, 20, 23–37. [Google Scholar]

- Merino-Pérez, L.; Segura-Warnholtz, G. Las políticas forestales y de conservación y sus impactos en las comunidades forestales en México. In Los Bosques Comunitarios de México, Manejo Sustentable de Paisajes Forestales; Bray, D., Merino, L., Barry, D., Eds.; Instituto Nacional de Ecología: Mexico City, Mexico, 2007; pp. 77–98. [Google Scholar]

- INEGI (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía). Conjunto de Datos Vectoriales de Uso de Suelo y Vegetación, Regiones Estadísticas: Escala 1:250 000 de México. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/biblioteca/ficha.html?upc=889463173359. (accessed on 12 November 2019).

- Almeida-Leñero, L.; Figueroa, F.; Ramos, A.; Calzada-Peña, L.; Galván-Benítez, L.E.; Hoth, J. Estrategia para la Conservación del Bosque de Agua: Diagnóstico Participativo de la Comunidad de San Miguel Topilejo; Conservación Internacional: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schuschny, A.; Soto, H. Guía Metodológica: Diseño de indicadores Compuestos de Desarrollo Sostenible; CEPAL: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2009; p. 102. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, P. Los recursos de uso común en México: Un acercamiento conceptual. Gaceta Ecológica 2006, 80, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Durston, J. ¿Qué es el Capital Social Comunitario? CEPAL: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2000; p. 44. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuyama, F. Capital social y desarrollo: La agenda venidera. In Capital Social y Reducción de la Pobreza en América Latina y el Caribe: En Busca de un Nuevo Paradigma; Atria, R., Siles, M., Arraigada, L., Robinson, L.J., Whiteford, S., Eds.; CEPAL: Santiago de Chile, Chile, 2003; pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. El Gobierno de los Bienes Comunes: La Evolución de las Instituciones de Acción Colectiva; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Vidaña, D.L. Cadena de Valor Maderable y Gobernanza de los Recursos Forestales del Ejido Gómez Tepeteno, Tlatlauquitepec, Puebla. Master’s Thesis, Colegio de Postgraduados, Texcoco, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Merino, L. La heterogeneidad de las comunidades forestales en México. Un análisis comparativo de los aprovechamientos forestales de las nueve comunidades consideradas. In El Manejo Forestal Comunitario en México y sus Perspectivas de Sustentabilidad; Merino, L., Alatorre, G., Cabarle, B., Chapela, F., Madrid, S., Eds.; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico; Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales (CLACSO): Cuernavaca, Mexico, 1997; pp. 91–105. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).