Abstract

Anthropologists sometimes ask what flexible practices mean when used in instances of land use and access among protected area regimes which control the land and the indigenous or local people who claim rights to the land. In the Mount Cameroon National Park (MCNP), West Africa, this question comes with urgency because of the historical disputes associated with defining access and user-rights to land within this park. In this case, we present an ethnographic study using a transect walk with a native Bakweri hunter to map and analyze his opinions about land use and access into the park. The findings show that, despite State prohibitions for this park, customary practices still occur for mutual reasons, whereas, in situations of disputes, other practices continue on the land unnoticed. We conclude that this flexibility is indicative of reciprocal negotiations and cultural resilience that preserve not only the biodiversity of the park but also the culturally relevant needs of people.

1. Introduction

Systems of land use and access have evoked a lot of interest among anthropologists investigating human–environmental interactions [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. While these authors contribute to knowledge about alternative forms of land use, questions still remain about how people act flexibly on the land amidst systems for protected areas. Movement and flexibility enable people to respond better to changes in their physical and social environment [8]. Therefore, in this article, we further engage with flexibility along the lines of [9] study of land access, which explores how local people make use of multiple sets of rights in disputable situations. This provides us with an alternative view on conflict of law (conflit de droit) [10]. With the notion that humans affect the natural state of land [11,12,13], through land uses that trigger State intervention [14,15], we argue that an analysis of flexibility gives new insights about land use and access in exclusionary environments of conservation.

At such locations, the formation of power creates segregation where practices of social groups exist [5]. It eventually leads to what the authors of Reference [16] described as ‘land claims’ by people detached from their land. Circumstances of this nature influence flexible behaviors that are an indirect outcome of institutional despotism [17] and a conflict of language (conflit de langage)’ [10] where elements of exclusion and capitalist accumulation exist. Failure to address these lapses hinders the effectiveness of plans to recognize the customary rights of people residing at the fringes of protected areas.

Mount Cameroon National Park (MCNP) is an example for which we can explore the notion of flexibility. MCNP was created in 2009 as part of the government’s Permanent Forest Estate (PFE) initiative, dedicating it under State protection [18], in commitment to the 1992 UN Convention on Biodiversity. The park includes six vegetation types including the lowland forest at elevations of 0–800 m, sub-montane rain forest at 800–1600 m, upper montane rain forest at 1600–1800 m, montane scrub at 1800–2400 m, montane grassland at 2000–3000 m, and sub-alpine grassland at 3000–4095 m [19] (p. 81). Considering that mammals such as drills, chimpanzees, preuss monkeys, and forest elephants remain endangered, the State implemented a 1994 forestry and wildlife law and a 2014 co-management plan to ensure park management, but with lapses due to the top–bottom nature of management [20,21] and the use of discussion forums, in which the local people have a minor influence on decision-making [22]. MCNP also includes four cluster conservation zones: Buea, Muyuka, Bomboko, and the West Coast [22] (p. 3), which are rich in biodiversity that the local communities partly use as a means of support for their living.

In the MCNP example, the Bakweri people rely on Mount Cameroon for a livelihood through the gathering of wild fruits such as the Dacryodes edulis (G. Don) H. J. Lam (bush pear) and other native spices like Irvingia gabonensis (Aubry-Lecomte ex O-Rorke) Baill. (African mango) used to complement farm income. Further, local communities around MCNP have, for several decades, interacted with groups from other parts of Cameroon who live as settlers and farmers working in cocoa farms and plantations created by the German colonial authorities in the 1880s [23]. However, while the Bakweri still largely rely on natural forests which entail conserving various products of cultural importance on the one hand, on the other hand, State mechanisms for conservation comes with challenges.

For instance, though the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP) adopted in 2007 emphasized ending activities that exploit indigenous people [24], the restriction of indigenous access to land by the park administration still takes many micropolitical forms, and State authorities defy certain claims of local knowledge. It is noted that Mount Cameroon has long been of ancestral value to the Bakweri and a source of retaining spiritual intervention to protect the land [25]. Thus, while the park should represent what the authors of Reference [26] called ‘free-range land’ preserved for its spiritual importance to the society, the State uses strict rules to define land use rights. This is why there are resentments between the park regime and local land users [21].

According to the authors of Reference [27], the Bakweri are one of the early groups of the Bantu-speaking people in coastal Cameroon, who settled on the slopes of Mount Cameroon for its fertile volcanic soils, one of the reason for the Bakweri land problem that started an armed resistance against the German military from 1891 to 1894, resulting in land expropriation and displacement of the Bakweri who had been undergoing an endless struggle to retain their lands [28,29]. Also, although legalities exist regulating the rights for locals to use forests, there are no standard verdicts for them to exercise their customary rights in the park [21].

Considering this prejudiced space for defining land use and access, we need to examine whether individual accounts of interacting in the park could offer constructive knowledge for exercising customary practices in protected areas. To do so, we worked with a Bakweri hunter named Mola Njie, during an ethnographic inquiry among 17 villages of the MCNP between August to December 2017 (see also References [20,21]). This study targets three objectives: (1) demonstrate that land use and access in this park is reminiscent of the historical and fragmentary nature of State power, (2) using an example of a hunter’s land use, show how flexibility helps in meeting the livelihood needs in protected areas, and (3) analyze the parallels and contrasts between the case of the MCNP and experiences reported elsewhere for showing that resistance to and cooperation with State administrative power can occur simultaneously among the same people.

1.1. Anthropological Critique of Flexible Land Use Practices

The notion of flexibility has been crucial in understanding changing land use practices among rural people. The empirical example of the MCNP shows avenues for anthropological analysis of flexibility. It was particularly challenging to devise a method where the anthropological analysis of flexibility does not overlook the dynamics of inequality and micro practices of resistance.

1.2. Local Reaction to Colonization of Nature

With an ethos of flexibility, and with regards to land use and access in Cameroon’s protected areas, the authors of Reference [7] examined the alternatives and trade-offs of conservation when people are removed from lands of traditional value to make space for the protection of nature. In this example, the World Wildlife Fund introduced the Integrated Conservation Development Projects (ICDPs), for the Korup National Park. This was aimed at recognizing the equality of rural people as partners in executing plans for conserving areas that involve traditional lands. However, in practice, the Korup Project had little regards for recognizing indigenous people as decision-makers. The Korup Project was equally criticized for prohibiting gathering, hunting, and fishing activities of the local people living in areas defined by the boundary between Cameroon and Nigeria, which the local population relied on for livelihood. As such, many of the locals expressed their wishes to disobey State orders for the simple reason that these orders use procedures which are aimed at seizing lands and traditional user-rights in the name of conservation [7].

Such protests often lead to serious problems in governing Cameroon’s national parks, where the exclusionary nature of protected area regimes is based on State laws that often do not take into consideration the traditional rights of people but create disputes between local people and park managers [6]. Consider also the Pygmies of Cameroon, whose livelihoods were affected by the establishment of national parks, prompting their exclusion from the benefits of development [30]. It is in this vein that park authorities almost always fail to truly integrate the beliefs and knowledge systems of the local people within the very institutional fabric of land use and access in protected areas. The authors of Reference [31] noted that excluding local communities from protected areas also undermines the objectives of conservation by creating disputes between local people and park management authorities. In their analysis of MCNP, they showed that local resistance against biodiversity conservation manifested in the everyday struggle for adaptive livelihoods. Such a struggle has been a result of many factors. For instance, population growth, disrupted kinship systems and rights to use and access of resources, loss of property, and no compensation, prompting the locals to set fire to portions of the forest, clearing plots for farming, extraction of honey, and hunting, despite warnings from park authorities.

The above narratives, at large, lay underneath the complicities of what the authors of Reference [3] termed ‘colonization of nature’, where institutional forms of power exert a conquest of the land, which is also similar to what the authors of Reference [32] specified as ‘resistance as thought and symbol’, a line of action conceived in constant dialogue or communication towards social justice. These conceptions raise the empirical question of whether locals engage in support, opposition, or both towards the park regime, through flexible use of protected areas. Among the Bakweri, for instance, the dynamic nature of power has been an issue of inequality between actors and locals with claims of rights to land use who become victims of resource governance on the one hand, and State authorities who administer the land (see also Reference [20,21] for more on relations among the actors). Before the coming of the MCNP, the Bakweri had for many generations settled on the slopes of Mount Cameroon as hunter-gatherers, and later as agriculturalists [27]. Many of them, living previously in small enclaves on the mountain, had established territories but later became victims of historical and fragmentary State power, such as the German colonizers who became legal owners of lands formerly occupied by ethnic groups after the Bakweri wars in the 1890s. This led not only to the removal of people from their land but also to the establishment of plantation agriculture [28] and the introduction of State systems for territorial management. Such practices incited land disputes which continued in Cameroon [10,29].

In effect, the Bakweri engaged with the land in similar ways to that of the people with whom the authors of Reference [9] worked: amidst regime efforts to regulate local land ownership, people employ flexible means of retaining land use rights. They continue to find ways for asserting the sovereignty of ownership and rights to their lands around Mount Cameroon [33]. The first move, in 1946, was to create the Bakweri Land Committee (BLC), an assembly of traditional rulers, notables, and elites, aimed at regaining control over Bakweri lands. Following a series of petitions launched by the BLC to the Trusteeship Council of the United Nations in New York, the Colonial Office in London, and colonial authorities in Nigeria, British colonialists adamantly ceded plantations to a newly created Cameroon Development Corporation (CDC) in 1946 as a public body, though the CDC only opened grounds for land privatization to various enterprises based on a Presidential Decree in 1994 [29].

Following Cameroon’s independence in 1961, a subsequent 1974 land tenure law distinguished State lands and private lands, eradicating all former claims for Bakweri land and confiscating these lands [33]. These processes bifurcated traditional authority into ‘subjects’, where they became custodians of the State, instead of a kinship basis for custodianship of the land [34,35]. In legal terms, the 1974 land tenure law defined State lands as lands “not classed into the public or private property of the State and other public bodies […] which the State can administer in such a way as to ensure rational use and development, and can be allocated by grant, lease, or assignment on conditions to be pursued by decree” [29] (p. 122).

Beneath the 1974 law, private lands “guarantee their owners the right to freely enjoy and dispose of them” [29] (p. 122). In spite of another petition by the BLC to the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights in 2002 for violating the rights of the Bakweri over ancestral land occupied by the CDC, the decision came with domestic remedies giving the local courts the green light to resolve the dispute. This case raised several issues about the competence of local courts to handle such disputes. Despite these petitions, a prolonged and unresolved problem of land use and access continues to exist between the Bakweri and State authorities.

Another explanation for this flexibility through the Bakweri land problem can be linked to structural adjustment initiatives in Cameroon. From the 1980s, economic crises arose following a fall in the prices of export products. Thus, an alliance between State authorities and agents of structural adjustment, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, emerged to rationalize the agro-forestry sectors in Cameroon [20]. A much implicit outcome of the structural adjustment was the promulgation of a State forest reform in 1994 for governing the use of forests following the Cameroon government’s signing of the 1993 UN Convention on Biological Diversity. The 1994 forestry law in Cameroon grants user-rights to locals, stating that it recognizes the right for local people to harvest forest resources for personal use, with the exception of those resources under State protection. However, the State reserves the power to permanently or temporarily suspend this right when there is a need of public interest [36]. This again reflects the historical and fragmentary nature of State power.

We can, therefore, note that the coming of colonial and State authorities did alter the traditional basis for land use and access. Although land reforms were introduced for the partial exploitation of forest resources, the criteria for doing so gave little clarity for the customary rights of the people. The upshot of this fragmentary power over the land likens to the authors of Reference [37]’s notion of ‘land-grab’, where people become part of labor practices in the search for jobs on land they previously had entitlements to, now placed under regime control. This reflects the current situation of land use and access on the MCNP, which warrants a further discussion about flexibility and its role in achieving local needs in protected areas. Previous analysis of villages around the MCNP showed that, in spite of discussion forums (village committees) through which locals partake in the State’s agenda for resource management, the seeming co-existence of State land use and customary practices often result in dynamic and micro-practices of inequality yielded in the paradoxical nature of co-management and disputes over land claims [20,21]. Nonetheless, understanding that the dynamics of land use and access can also include acts of territoriality [8,15,26,38,39,40] to satisfy basic needs and preserve cultural practices, in this article, we examine whether the above remarks might apply to the MCNP and to what extent it meets livelihood needs in protected areas.

2. Materials and Methods

We used an ethnographic inquiry with the aid of a transect walk, site mapping, and narrative analysis to make sense of various sites in the Buea and West Coast clusters of the MCNP. We relied on the opinions of a single key informant given that previous studies focusing on discussion forums (forest management committees), through which locals partake in the State’s agenda for resource management, yielded little analysis about the nature of land use and access in the MCNP [20,21,22]. According to the authors of Reference [41], in ethnographic research, a transect walk involves a walk through a site with a willing resident who is requested to share personal experiences about historical and culturally significant areas.

The transect walk comprised of the following phases: (1) a preparatory phase, which included acquiring background information through the study of maps and leaflets and obtaining authorization from the technical staff at the office of the MCNP in Buea, (2) getting an orientation about the terrain from local knowledgeable people, and (3) a journey to the MCNP guided by the selected native hunter. Being in his late forties, the hunter belongs to the Bakweri group, and lives in one of the communities at the southwestern slope of Mount Cameroon known today as Buea town, which is located approximately less than 7 km from Bova village. His community comprises of Bakweri people who engage in various forms of economic activities with traders from regions elsewhere. Having spent more than 25 years of living in the area with his relatives, and now with his family of two children, Mola Njie has performed on many occasions not just as a leading tour guide but as a member of several committees dealing with the management of the park and its surrounding villages. To him, hunting has been a practice he did from childhood, though it gradually became limited due to new laws restricting the exploitation of wildlife in protected areas. As such, acquiring a First School Living Certificate at his childhood age enabled him to become involved with other activities for a living, such as being an educator and facilitator for tourism in Buea, furthering his career as a professional driver, and working for the Buea Council within the last fifteen years. The MCNP authorities, however, permit the hunting of animal species considered by law as not endangered. This takes place in forests not under state protection such as those on privately owned land and community land, which enables him hunt part time. (4) The next phase included briefing sessions with a team of tour guides during the walk, and (5) conducting interviews with the hunter aimed at ascertaining his perceptions of land use and access by the local people into the park. We made notes during the walk and used tools which included a camera, a voice recorder, and Global Position System (GPS) equipment, for recording field observations and recording geographical coordinates of important sites which were indicated by the hunter (Figure 1).

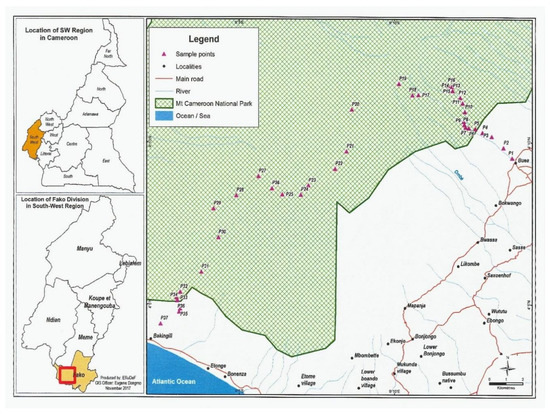

Figure 1.

Location of sites on the Buea and West Coast of Mount Cameroon National Park (MCNP) where we collected data. Note, we designed the map using the points (P) collected on the Buea and West Coast clusters of MCNP during fieldwork.

A transect walk has the merit of enabling the researcher to cope with challenges in interactive platforms and of disclosing different viewpoints about a given area [42,43,44]. A transect walk is also a useful means for site mapping [42]. Anthropologists have used site mapping in participatory research to examine community needs and match them with bureaucratic decisions, and to identify knowledge of the state of situations based on the perspectives of the local people it claims to represent [45,46,47]. In this study, we adopted similar thinking to illustrate the hunter’s knowledge of land use and access on the MCNP using open-ended questions which targeted: (a) the hunter’s knowledge of traditional land use and access on Mount Cameroon a few years before and after the creation of the MCNP, (b) how the MCNP influences the land use attitudes of the people living close to the boundary of the park, and (c) determining to what extent officials of the park and members of the local community cooperate in the use of the MCNP. Our inspiration for the chosen methods we used came from the authors of Reference [48]’s views about obtaining data through face-to-face interactions of societal experience to describe how encounters are socially and culturally organized in particular situational settings.

Consistent with the authors of Reference [48]’s description of socially and culturally organized interaction in situational settings, we focused on tracking the hunter’s movement and meanings of the stories he told while visiting various sites in the park. For us to provide a descriptive analysis of these accounts, we adapted the author of Reference [49]’s descriptive concepts on the application of narrative analysis (Table 1). This approach enabled us to derive meaning from relevant accounts of the hunter.

Table 1.

Using Riessman’s [49] (p. 2–5) concepts in the narrative analysis of ethnography.

3. Results

3.1. A Hunter’s Way of Knowing the Land

The key informant in question, Mola Njie, is a man whose parents and close relatives were hunters. He therefore had the opportunity to hunt prior to the creation of the MCNP. Thus, his knowledge of the terrain was an added merit to our study. Before meeting Mola Njie, we had learned from a land surveillance expert about the assistance he gave to a group of researchers back in 1999 when Mount Cameroon erupted. We present below the hunter’s narrative of land use and access in the park, with a particular focus on some of the products he described during fieldwork (Table 2). In the discussion section, we then compare our findings on flexibility in the park with information from cases reported on the subject in the literature.

Table 2.

Distribution of forest products and their use.

3.2. Adapting Local Land Use to the Park Regime

Here, we use the word ‘informal’ to refer to ‘unnoticed forms’ of land use and access into the park by the local people despite State prohibitions. An example of such incursions into the park is seen during the practices of traditional camping and the gathering of forest products in parts of the sub-montane forest, close to the park boundary. These practices, among others, differed from what occurred in remote parts of the park, where people use the land rather for rituals and tourism activities. In the paragraphs below, we describe these forms of land use at localities indicated on the map (Figure 2) as GPS points (P).

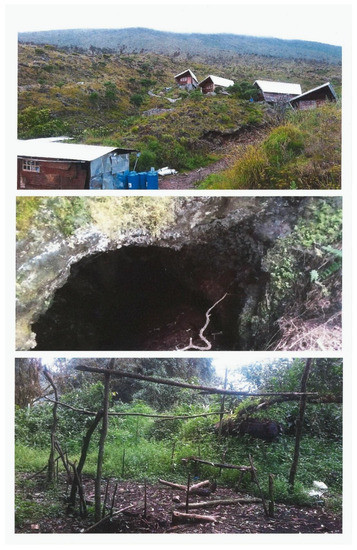

Figure 2.

Land use on the MCNP comprising tourism development (top), an ancestral cave (middle), and a traditional camp (bottom).

Our results indicated evidence of forest products which had been gathered and the setting up of traditional camps in the park. The area between P5 and P9 on the map (Figure 2), are sites of such camps which have been constructed in the sub-montane rain forest close to the park boundary. Here, we see the remains of plants of traditional importance which are used for medicinal and household needs. According to Mola Njie, many medicinal plants in this territory rarely grow in the local communities, which in effect explains the reason why people in need of such plants are obliged to trespass and collect them specifically for use in rituals and village cleansings. To name just a few of such plants in Mokpwe (Bakweri language), we have: the Wulule, which is used during family ceremonies called Yoya’a etumba and the elephant dance festival by the Maale sacred society, the Ewula vaco, which is a grass used for the treatment of wounds, and the Monda dwani, which is a sugarcane consumed as an alternative source of body strength during exhausting farm work. Mola Njie also talked about the Ewula-maija, which is a plant he consumes as tea, and as a source of blood supply. Furthermore, people also use a peace plant picked from this area to mark land boundaries and to prevent conflicts between landowners. These examples are part of the flexibility, which the hunter describes as an informal way of using the land, even when the State does not formally approve such activities in protected areas.

Walking through the forest, Mola Njie remembered his youthful days when he visited the mountain to harvest a leaf (rau-rau). When asked about this leaf, he noted that technological development and the introduction of plastic papers in grocery stores were gradually replacing the habit of using the leaf for storing doughnuts (puff-puff and akra), as he put it:

“When we close after school, we go to the bush and get leaves to sell puff-puff and akra. All those things when they tie it on this leaf, you enjoy it. It gives the food a different taste.”

To Mola Njie, although State conservation laws prohibit the unauthorized entry of people to the park, one reason for acts of trespassing was due to the closeness of ‘village land’ to the boundary of the park. These are farmlands which are used by the local population who live in nearby communities. For this reason, the authorities of the park carry out periodic arrests for unauthorized incursions into the park.

There are habitats of trees such as the Mahogany, the Iroko, and the Whitewood close to P8 (Figure 2). While holding a leaf from one of these trees, Mola Njie explained that periods before the advent of the MCNP, these habitats were a source of firewood and materials used for house construction. Nowadays, State forestry laws prohibit the extraction of wood on this site. To Mola Njie, the management regime assists him with ‘user-rights’ under conservation agreements. These rights allow individuals to cultivate tree species in villages, similar to the ones found at P8, to reduce logging in the protected areas. The regime’s provision of user-rights enables him to have alternatives for cultivating and harvesting various tree species away from the park. The flexibility, in this case, consists of local acceptance of alternatives provided by the State, while at the same time, they continue accessing areas inside of the park.

Portions of the sub-montane rain forest consist of land for cultivating Prunus Africana (a plant for cancer treatment). To Mola Njie, the collection of Prunus Africana on Mount Cameroon goes back to the 1970s, when no restrictions existed, and this tree was used for the treatment of many other illnesses. The park regime, using what Mola Njie called a ‘Prunus Africana bark trade’, collaborates with a partner agency, Mount Cameroon Prunus Management Company (MOCAP), through which locals gain employment as a harvester of the Prunus Africana bark. According to Mola Njie, this initiative offers a flexible choice for him to become a village member of harvesters’ unions through which he obtains basic needs. Under this system, union members plan income-generating activities from which he acquires a drinkable water supply and healthcare services. This shows that the State was able to accommodate flexible access regimes to the areas inside the park.

On entry into a traditional camp at P30, Mola Njie pulled out a bottle of water from his bag and while staring up at the sky, as if to say the night is near, he recounts how he worked as a contracted harvester of Prunus Africana bark in the year 2006 for a pharmaceutical company, Plantecam. The traditional camp consisted of sticks from the forest, positioned into the ground with piles of wood for resting, and a fireplace in the middle of the camp (Figure 2). He narrated how he spent days on the mountain during harvesting activity and stated that he and his colleagues used the camp for shelter after lengthy periods of trekking and transporting Prunus Africana barks down the slopes of the mountain.

We also identified accounts of human activity in the wildlife forest of the park, as well as rituals and stories about hunting. The wildlife forest is located on the West Coast of the MCNP between P25 and P28 (Figure 2). This area represents a habitat for forest elephants, monkeys, and chimpanzees. According to Mola Njie, elephants are of spiritual importance to the Bakweri. They symbolize mid-way communication between ‘the living’ and ‘the dead’. Mola Njie actually abides by this belief in elephant spirituality and explained that this spiritual relationship enabled him to avoid hostilities with elephants when visiting the wildlife forest. Since this area is a few kilometers from the boundary of the park and the village settlements, the elephants come to feed on crops grown on nearby farms. When they do, they leave behind dung, which, to Mola Njie, is a useful form of traditional medicine which is used for the treatment of stomach aches if taken after boiling it in water. This explains why there is a tendency for the local population to collect dung under situations which are unnoticed by the authorities of the park.

To Mola Njie, the appearance and state of the dung gives an idea of the size and location of an elephant in the park. Such knowledge is important for it enables one to avoid any confrontations with elephants while in the wildlife forest. We see a further indication of this knowledge in the hunter’s ability to determine an elephant’s location based on the number of insects on the dung. A greater number of insects gives the idea that an elephant is nearby. The hunter also associates larger sizes of dung to adult elephants. In Mola Njie’s view, the use of such knowledge helps him avoid any confrontations with the elephants and enables him to move about the forest without disturbing these animals. Consequently, while the park authority prohibits the free entry of the local population into the park, we see that there are other means of using the land to satisfy livelihood needs. The fact that this means of engaging with the land takes place in ways that protect elephants while acquiring the dung for medicinal needs, is indicative of the aspects of flexibility in using protected areas.

Ritual needs are one of the evident explanations for the traditional use of the park. As [50] puts it, religious systems are ultimately a study of the people themselves and are the strongest elements which influence the lives of Africans. As such, we cannot understand the concerns of the Bakweri without knowing the traditional beliefs, attitudes, and practices that underpin their religions. The results of the interviews showed that rituals are connected to beliefs in a spiritual being and to the protector of Mount Cameroon, known as Efassa moto. To the hunter, this spiritual being is a source of strength and protection to the Bakweri. Consequently, he maintains the necessity of using the land on the mountain for rituals. An example of practicing a ritual was at P11 (Figure 2), where a huge rock known as the ‘dancing stone’ (Lyen la ngomo’o) was located. Mola Njie perceived this stone to symbolize a spiritual figure which has been worshipped by past generations of the Bakweri. He equally stated that the officials of the park actually support this form of worship because it ensures the safety of visitors to the park.

At the site of the rock, Mola Njie requested that we harvest a fern plant and perform a dance to invite Efassa moto to protect us on the mountain. The ritual entailed dancing to the tune of music sung by the hunter with the phrase: Lyen la ngomo’o Iye Iye. This song praises the Bakweri ancestors and spiritual beings on the land while also requesting them to protect visitors to the park from danger. To the hunter, there are beliefs that in past years, people who failed to perform the dancing stone ritual went missing on the mountain and were never found. In this manner, the authorities of the park cooperate with local land users to maintain this form of flexibility in order to ensure the safety of visitors in the park.

We also visited an ancestral cave which was located a few kilometers from P18 and here, Mola Njie explained that he and his forefathers used the cave for shelter during the hunting seasons and the ancestral worships (Figure 2). Nowadays, this site is maintained as a tourist attraction. Another reason for maintaining ritual beliefs in the park is related to the volcanic eruptions of this mountain, which recently erupted in 1959, 1982, 1999, and 2000, leading to the destruction of biodiversity. To Mola Njie, volcanic eruptions are a sign of Efassa moto’s resentment against the people’s failure to perform rituals on the mountain. As such, when the lava flows damage crops on the land, the Bakweri perform rituals using animal sacrifices as a request for Efassa moto to restore environmental stability. These examples are indicative of how local land users are flexible in pursuing their traditional use of the land.

On the issue of hunting, areas close to the P8 site were a hunting attraction before the creation of the MCNP. Here, Mola Njie recalls his youthful encounter with a tree that represents a camping spot for bush rabbits (he called the spot postman-poto or Loka), as he explained:

“When I used to come here to hunt, the rabbit slept on this tree all day. At six o’clock in the evening, the rabbit would come down from the tree in search of food. Upon returning in the morning, the rabbit would make a screaming sound aimed at deceiving any predator that it was descending from the tree, whereas it was climbing up the tree to sleep. The predator would then arrive later beneath the tree, just to realize that the rabbit had returned to its nest.”

Another hunting site is located in the montane grassland section of the park. Here, Mola Njie took us closer to a patch of grass where he explained the practice of hunting and trapping of an antelope at site P18, stating that:

“There was a bush with two exit holes in the middle of two footpaths. In this bush, there was an enclosure where antelopes sheltered during cold weather. Two men had to stand on both sides of the exit holes to get an antelope trapped using sharp sticks.”

In trapping the antelope, to him, the process was difficult because success was based on how careful and silently the hunter approached the animal. Due to this difficulty, Mola Njie sold a mature antelope at about 65,000 francs (99,44 euros) a few years before the creation of the MCNP. We should note, however, that nowadays, the park authority does not approve of such means of land use in this protected area.

The remote parts of the park consist of lands used for tourism development (Figure 2). Thus, although the regime prohibits hunting on the land, it promotes tourism by cooperating with some members of the local communities in activities that generate income. We observed footpaths that had been created on the land and newly constructed huts to be used by tourists. According to the hunter, a few years before 2009, the local people used these footpaths during bee farming, as he recounted:

“Back in the days before the MCNP, we trekked for long distances to the Savannah grasslands where we lit fires to get the bees out of their holes in order to collect the honey.”

In perspective, Mola Njie referred to footpaths as ‘shortcuts’ that were crucial before the creation of the park. Footpaths were shorter connections between villages which were located around Mount Cameroon. In recent years, mainly tourists and village inhabitants employed to perform in income-generating activities for the regime make use of these footpaths.

At the montane grassland, a road developed for tourism activity linked the points P23 and P25 (Figure 2) to one of the adjacent villages, i.e., from Bonakanda village in Buea through P25 to a place at P29 known as Mann-Spring lodge. Constructed in 2015, this road facilitated the transportation of equipment to furnish the tourist lodge at Mann-Spring. Mola Njie maintained that Mann-Spring lodge was a former camping spot used by Bakweri hunters before the arrival of a German Botanist, Gustav Mann, who, in 1862, found a spring in the area while collecting plants. Tourism is an example of flexibility where the hunter can cooperate with park authorities in using protected areas for his benefit. Mola Njie names a few friends of his, who were employed by the regime as tour operators, guides, and porters, adding that although they earn some money from tourism in the park, most of the finances from tourism go to the State treasury. Mola Njie expressed the need for initiatives that can be sponsored with funds from such finances in order to achieve the basic needs of the local people.

4. Discussion

The previous sections demonstrated the fragmentary nature of State power and its influence in shaping practices of land use and access. In doing so, we used the case of the MCNP to explain a native hunter’s knowledge of flexibility in land use and access, underlining how local people adapt to new ways of State control without abandoning their land use practices. There are connections between the case of the MCNP and experiences elsewhere in the literature.

The authors of Reference [7]’s study of the Korup National Park revealed how State power beneath the influence of foreign donors (conservationists) transformed the Korup landscape by removing people from the land, adopting forestry laws, and prohibiting the continuity of traditional land use. Similarly, in the Boumba-Bek national park, the park regime detached the Baka pygmies from the benefits of land use [30]. In the case of the MCNP, these patterns of institutional power depict a land conquest [3] and the exclusionary nature of protected area regimes [6,10]. Here, park authorities utilize State forestry laws and co-management plans to prevent the unofficial use of the park. Through these mechanisms, the regime retains the power to sanction people who violate State laws for protected areas.

A reaction to the above means of State control are acts of resistance [31,32]. Here, flexibility is shaped by how the local population uses alternative means to meet their needs in situations of dispute [9]. For instance, in the Korup case, the local population shared a common view of disobeying State laws in resentment of procedures that expropriate village land [7]. In another case, when the government of the Dominican Republic issued protection laws over the Ebano Verde area, the locals of El Arroyazo and La Sal began gathering forest resources without authorization from the State due to inadequate compensation from the regime [15]. Furthermore, the Laponian World Heritage area in Sweden involved several parties (non-governmental agencies, business representatives, and local people) with varied interests seeking managerial control over the land, making it hard for the local Saami to exercise their rights. Saami reindeer herders argued for indigenous control over the management of Laponia and asked for a majority of seats in the management board, though this came under opposition from State officials and politicians [14].

The hunter’s account about the Bakweri displays a subtler form of resistance. He reveals the often-untold use of sites by locals who are close to the park boundary for gathering forest products for medicinal and traditional needs. Previous experiences of open resistance by the Bakweri turned out to be unsuccessful when they tried to change the official rules of the regime to something similar to that of the Laponia case. Therefore, the silent continuation of traditional land use practice in ignorance of the law can be classified as acts of subtle resistance.

In contrast, flexibility in maintaining cultural continuity might not always be classified as resistance, but the general sense of creating space for attaining other needs. For instance, in Siberia, land use and acquisition among the Evenki are conceivable by an individual’s good performance on the land, in what Anderson called ‘power, sovereignty, and license without sanctions, nor land exclusions’ [38] (p. 120). The Yamal-Nenets in the Tundra exert a flexible behavior on the land by using ancient practices of local hunting and fishing as alternative subsistence to reindeer herding in spite of a contemporary economy where the Soviet and post-Soviet territorial organization governs economic activities [8]. Among the Saami in Finnish Lapland, flexibility can be perceived through attitudes of telling very little about place names to outsiders so as to defend the land against external encroachment [40].

The MCNP case presents another picture to the above narrative, which we observe as acts of cultural resilience. Consistent with the author of Reference [50]’s assertion about religious systems that define people, our analysis showed that the park continues to be a place of spiritual importance which the hunter has much regard for through ritual practices in the worship of a spiritual beings that keep people away from dangers. Within this form of resilience, people tend to accommodate new knowledge of land use such as alternative ways of cultivating trees without necessarily abandoning their traditions. This analysis seems consistent with the authors of Reference [8]’s conclusion about the Yamal-Nenets, who adjust new elements to their own needs without changing their traditional ways of living on the land.

The author of Reference [26] distinguished between free-range land and lands with strict rules of acquisition. Instead of both categories existing as distinct in different cultural settings as Casimir implied, the MCNP case showed that both categories co-exist on the same piece of land, where the space for flexibility among land users is informed by collaboration and reciprocity. According to the hunter, park authorities work together with locals to implement conservation plans through income activities, such as in the Prunus management scheme and tourism development. This, in return, supports the economic needs of people, enabling them to earn income which they use to obtain basic needs for their families. Further, the regime partly endorses valuable ritual practices, such as the dancing stone, to secure the safety of people performing various tasks of State interests in the park.

The hunter’s narrative and its analysis show how the Bakweri operate in two simultaneous ways, by collaborating with the State regime where it provides positive alternatives to using parklands, while at the same time continuing culturally embedded practices silently as acts of subtle resistance to the regime.

5. Conclusions

Considering the frictions between human activities in parks, this study underlined the need to examine flexible land use and access in exclusionary systems of protected areas. Previous anthropological studies on land use and related practices have not given much attention to how the notion of flexibility in land use and access occurs in dispute situations where locals and park regimes co-exist on the land. To address this question, we used the example of the MCNP to explore the historical and fragmentary nature of State power, a hunter’s testimonies of flexibility, and connections between the MCNP case and experiences elsewhere. The results showed that the current state of land use and access on the MCNP is reminiscent of institutional power and historical patterns of State fragmentation—mechanisms that continue to enable the regime to exercise control on the land. This leads to a situation of reciprocity where the State involves the locals in the park through income activities in return for attaining conservation needs; whereas, the locals welcome the good things about the State giving access to the park, and simultaneously practice covert forms of resistance through trespassing where access to the parklands is prohibited. Therefore, resistance to and cooperation with State power can occur simultaneously among the same people.

Thus, this article shows that land use and access in protected areas are more flexibly negotiated than it may seem from reading existing literature. A more fine-grained analysis of local flexibility in accessing parklands indicates that a national park does not have only good or only bad consequences for local livelihoods. The hunter’s knowledge and practice reveal that the Bakweri flexibly accommodate new forms of land use regulations without abandoning their traditional ways of using the land. Here, the flexible use of the land is driven by cultural resilience to preserve one’s spiritual connection to the land, as well as by acts of reciprocity between park authorities and locals. Thus, in exclusionary forms of conserving protected areas, flexibility can involve practices that locals convey to resist as well as comply with regimes for their benefit.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.N.; Methodology, A.A.N.; Investigation, A.A.N.; Writing—original draft preparation, A.A.N.; Writing—review and editing, N.M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Lapland Graduate School Grant 2019.

Acknowledgments

Our gratitude to the staff at the Arctic Centre and the Graduate School Committee at the University of Lapland, for supporting the lead author financially and technically in writing this article. Florian Stammler and Seija Tuulentie supervised the lead author in writing this article and we are grateful to them. We acknowledge Anna-Liisa Ylisirniö, who prepared the lead author towards his fieldwork in Cameroon, and Peter Loovers, Samuel Ndonwi, and Lum Suzanne, who spent the time to improve the language of this article. Our work would not have been completed without technical support from the ERuDEF, park management authorities at MCNP, and the Cameroon Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife. Thanks to the hunter, Mola Njie, for his testimonies throughout our visit to the MCNP and to the anonymous reviewers and guest editors for the comments they provided.

Conflicts of Interest

There was no conflict of interest among the authors. The funders had no role in the design, collection, analyses, interpretation, writing, and publication of this study.

References

- Anderson, D.G.; Ikeya, K. Parks, Property, and Power: Managing Hunting Practice and Identity within State Policy Regimes. In Senri Ethnological Studies; Anderson, D.G., Ikeya, K., Eds.; National Museum of Ethnology: Osaka, Japan, 2001; Volume 59, pp. 1–200. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, B. Changing Protection Policies and Ethnographies of Environmental Engagement. Conserv. Soc. 2005, 3, 280–322. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge, and Description, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 1–288. [Google Scholar]

- Kopnina, H.; Shoreman-Ouimet, E. Environmental Anthropology Today, 15th ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–301. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.M. Politics, Interrupted. Anthropol. Theory. 2019, 19, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemunta, N.V.; Pascal, M.A.O. The Tragedy of the Governmentality of Nature: The Case of National Parks in Cameroon. In National Parks: Sustainable Development, Conservation Strategies, and Environmental Impacts; Smith, J., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Soltau, K. The Costs of Rainforest Conservation: Local Responses Towards Integrated Conservation and Development Projects in Cameroon. J. Contemp. Afr. Stud. 2006, 22, 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stammler, F. Reindeer Nomads Meet the Market. Culture, Property and Globalisation at the End of the Land. Halle Stud. Anthropol. Eurasia 2005, 6, 1–379. [Google Scholar]

- Plueckhahn, R. Rethinking the Anticommons: Usufruct, Profit, and the Urban. Available online: https://culanth.org/fieldsights/rethinking-the-anticommons-usufruct-profit-and-the-urban (accessed on 10 July 2019).

- Oyono, P.R. The Foundations of the Conflit de Langage Over Land and Forests in Southern Cameroon. Afr. Study Monogr. 2005, 26, 115–144. [Google Scholar]

- Cristina da Silva, T.; Campos, L.Z.; Balée, W.; Medeiros, M.F.; Peroni, N.; Albuquerque, U.P. Human Impact on the Abundance of Useful Species in a Protected Area of the Brazilian Cerrado by People Perception and Biological Data. Landsc. Res. 2017, 44, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ficek, R.E. Cattle, Capital, Colonization: Tracking Creatures of the Anthropocene In and Out of Human Projects. Curr. Anthropol. 2019, 60, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirier, N. Culture and Conservation: Beyond Anthropocentrism. J. Ecol. Anthropol. 2016, 18, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrom, A.N. Negotiating Wilderness in a Cultural Landscape: Predators and Saami Reindeer Herding in the Laponian World Heritage Area; Uppsala University Library: Uppsala, Sweden, 2003; Volume 32, pp. 1–535. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes, G. Defining the forest, defending the forest: Political Ecology, Territoriality, and Resistance to a Protected Area in the Dominican Republic. Geoforum 2014, 53, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koot, S.; Büscher, B. Giving Land (Back)? The Meaning of Land in the Indigenous Politics of the South Kalahari Bushmen Land Claim, South Africa. J. South. Afr. Stud. 2019, 45, 357–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamdani, M. Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism, 1st ed.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996; pp. 1–353. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, B.; Shu, G.N.; Steil, M.; Tessa, B. Interactive Forest Atlast of Cameroon. Available online: http://pdf.wri.org/interactive_forest_atlas_of_cameroon_version_3_0.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- Awung, N.S. Assessing Community Involvement in the Design, Implementation and Monitoring of REDD+ Projects: A Case Study of Mount Cameroon National Park—Cameroon. Ph.D. Thesis, University of New York, New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–357. Available online: http://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/11152/1/Final%20full%20thesis%20for%20submission%20Nov%202015.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Nebasifu, A.A.; Atong, N.M. Rethinking Institutional Knowledge for Community Participation in Co-management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebasifu, A.A.; Atong, N.M. Expressing Agency in Antagonistic Policy Environments. Environ. Sociol. 2019, 6, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awung, N.S.; Marchant, R. Quantifying Local Community Voices in the Decision-making process: Insights from the Mount Cameroon National Park REDD+ Project. Environ. Sociol. 2018, 4, 135–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laird, S.A.; Awung, G.L.; Lysinge, R.J. Cocoa farms in the Mount Cameroon region: Biological and cultural diversity in local livelihoods. Biodivers. Conserv. 2007, 16, 2401–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellier, I.; Hays, J. Scales of Governance and Indigenous Peoples’ Rights, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–294. [Google Scholar]

- Jong, V. Landscapes, Visual Arts, and Ecocritism: A Reflection on the Scenic Apertures of Mount Fako in Cameroon. Interdiscip. Stud. Lit. Environ. 2010, 17, 792–796. [Google Scholar]

- Casimir, M.J. The Dimensions of Territoriality: An Introduction. In Mobility and Territoriality: Social and Spatial Boundaries among Foragers, Fishers, Pastoralists and Peripatetics; Michael Casimir, M.J., Rao, A., Eds.; Bloomsbury Publishing PLC: London, UK, 1992; pp. 1–416. [Google Scholar]

- Ardener, E. Coastal Bantu of the Cameroons: Western Africa Part. XI, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, I.; Fanso, V. Encounter, Transformation and Identity: Peoples of the Western Cameroon Borderlands, 1891–2000; Berghahn Books: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 1–254. [Google Scholar]

- Ndiva, K. Asserting Permanent Sovereignty Over Ancestral Lands: The Bakweri Land Litigation Against Cameroon. Annu. Surv. Int. Comp. Law 2007, 13, 103–156. Available online: http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/annlsurvey/vol13/iss1/6 (accessed on 15 January 2020).

- Pemunta, N.V. The Governance of Nature as Development and the Erasure of the Pygmies of Cameroon. GeoJournal 2013, 78, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Akem, E.S.; Savage, O.M. Strategies of Resistance and Power Relations in the Mount Cameroon National Park. Int. J. Dev. Res. 2019, 9, 25501–25507. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.C. Weapons of the Weak: Everyday forms of Pleasant Resistance; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 1985; pp. 1–392. [Google Scholar]

- Konings, P. Chieftaincy and Privatisation in Anglophone Cameroon. In The Dynamics of Power and the Rule of Law: Essays on Africa and Beyond, in Honour of Emile Adriaan B. van Rouveroy van Nieuwaal; Binsbergen, W., Pelgrim, R., Eds.; African Studies Centre: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Geschiere, P. Chiefs and Colonial Rule in Cameroon: Inventing Chieftaincy, French and British Style. Afr. J. Int. Afr. Inst. 1993, 63, 151–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pemunta, N.V.; Fonmboh, N.M. Experiencing Neoliberalism from Below: The Bakweri Confrontation of the State of Cameroon over the Privatisation of the Cameroon Development Corporation. J. Hum. Secur. 2010, 6, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Cameroon. Law No 94/01 of 20th January 1994. Available online: http://www.droit-afrique.com/upload/doc/cameroun/Cameroun-Loi-1994-01-regime-forets-faune-peche.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2020).

- Li, T.M. Centering Labor in the Land Grab Debate. J. Peasant Stud. 2011, 38, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D. Identity and Ecology in Arctic Siberia: The Number One Reindeer Brigade; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 2002; pp. 1–272. [Google Scholar]

- Githitho, A.N. The Sacred Mijikenda Kayas of Coastal Kenya: Evolving Management Principles and Guidelines. In Conserving Cultural and Biological Diversity: The Role of Sacred Natural Sites and Cultural Landscapes, Proceedings of the Tokyo Symposium, Aichi, Japan, 30 May–2 June 2005; Schaaf, T., Lee, C., Eds.; UNESCO Division of Ecological and Earth Sciences: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzullo, N. Sápmi: A Symbolic Re-appropriation of Lapland as Saami Land. In Máttut-máddagat: The Roots of Saami Ethnicities, Societies and Spaces/Places; Äikäs, T., Ed.; University of Oulu: Oulu, Finland, 2009; pp. 174–185. [Google Scholar]

- Taplin, D.H.; Scheld, S.; Low, S. Rapid Ethnographic Assessment in Urban Parks: A Case Study of Independence National Historical Park. Hum. Organ. 2002, 61, 80–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betru, T.; Tolera, M.; Sahle, K.; Kassa, H. Trends and Drivers of Land Use/Land Cover Change in Western Ethiopia. Appl. Geogr. 2019, 104, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiffner, C.; Arndt, Z.; Foky, T.; Gaeth, M.; Gannett, A.; Jackson, M.; Lellman, G.; Love, S.; Maroldi, A.; McLaughlin, S.; et al. Land Use, REDD+ and the Status of Wildlife Populations in Yaeda Valley, Northern Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia, M.R.; Davidson-Hunt, I.; Berkes, F. Social–ecological Memory and Responses to Biodiversity Change in a Bribri Community of Costa Rica. Ambio A J. Hum. Environ. 2019, 48, 1470–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthias, P. Ambivalent Cartographies: Exploring the Legacies of Indigenous Land Titling through Participatory Mapping. Crit. Anthropol. 2019, 39, 222–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, M.; Lamb, Z.; Threlkeld, B. Mapping Indigenous Lands. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2005, 34, 619–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maman, S.; Lane, T.; Ntogwisangu, J.; Modiba, P.; Vanrooyen, H.; Timbe, A.; Visrutaratna, S.; Fritz, K. Using Participatory Mapping to Inform a Community-Randomized Trial of HIV Counselling and Testing. Field Methods 2009, 21, 368–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcez, P.M. Microethnography. In Encyclopedia of Language and Education; Hornberger, N., Corson, D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1997; pp. 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riessman, C.K. Narrative Analysis. In Narrative, Memory and Everyday Life; University of Huddersfield: Huddersfield, UK, 2005; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Mbiti, J.S. African Religions and Philosophy, 2nd ed.; Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 1990; pp. 1–288. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).