Nursery Cultural Techniques Facilitate Restoration of Acacia koa Competing with Invasive Grass in a Dry Tropical Forest

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Nursery Treatments

- Hawaii dibble tube: 49 cm3 volume, 2.5 cm diameter × 12 cm depth, and tray density of 449 containers m−2 (Pacific Allied Products, Ltd., Kapolei, HI USA).

- Ray Leach “cone-tainer” SC-10: 164 cm3 volume, 3.8 cm diameter × 21 cm depth, and tray density of 528 containers m−2 (Stuewe and Sons, Inc., Tangent, OR USA).

- Deepot 40 (D-40): 656 cm3 volume, 6.4 cm diameter × 25 cm depth, and tray density of 174 containers m−2 (Stuewe and Sons, Inc., Tangent, OR USA).

2.2. Outplanting Site and Experimental Design

2.3. Measurements and Data Analysis

3. Results

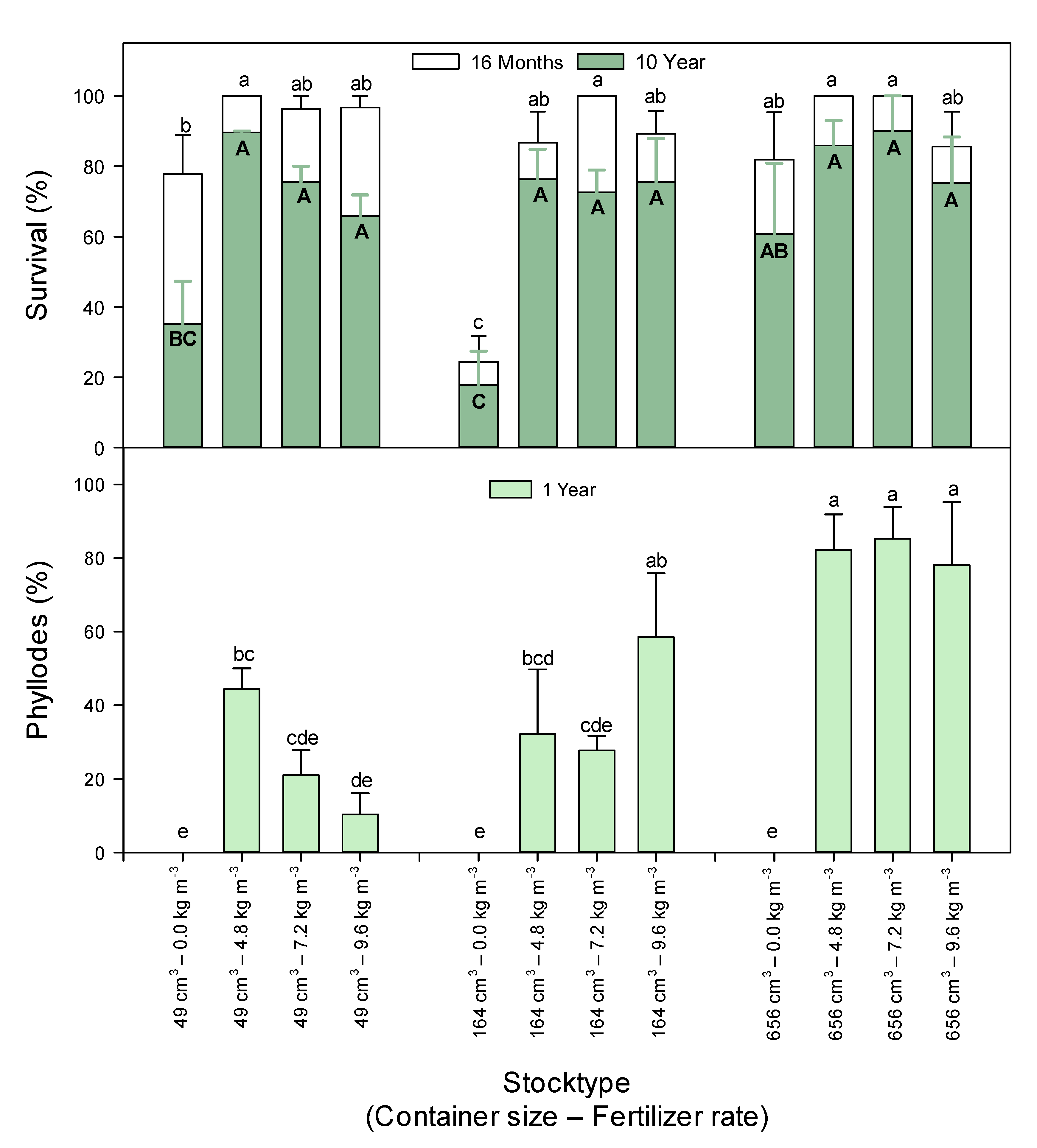

3.1. Survival

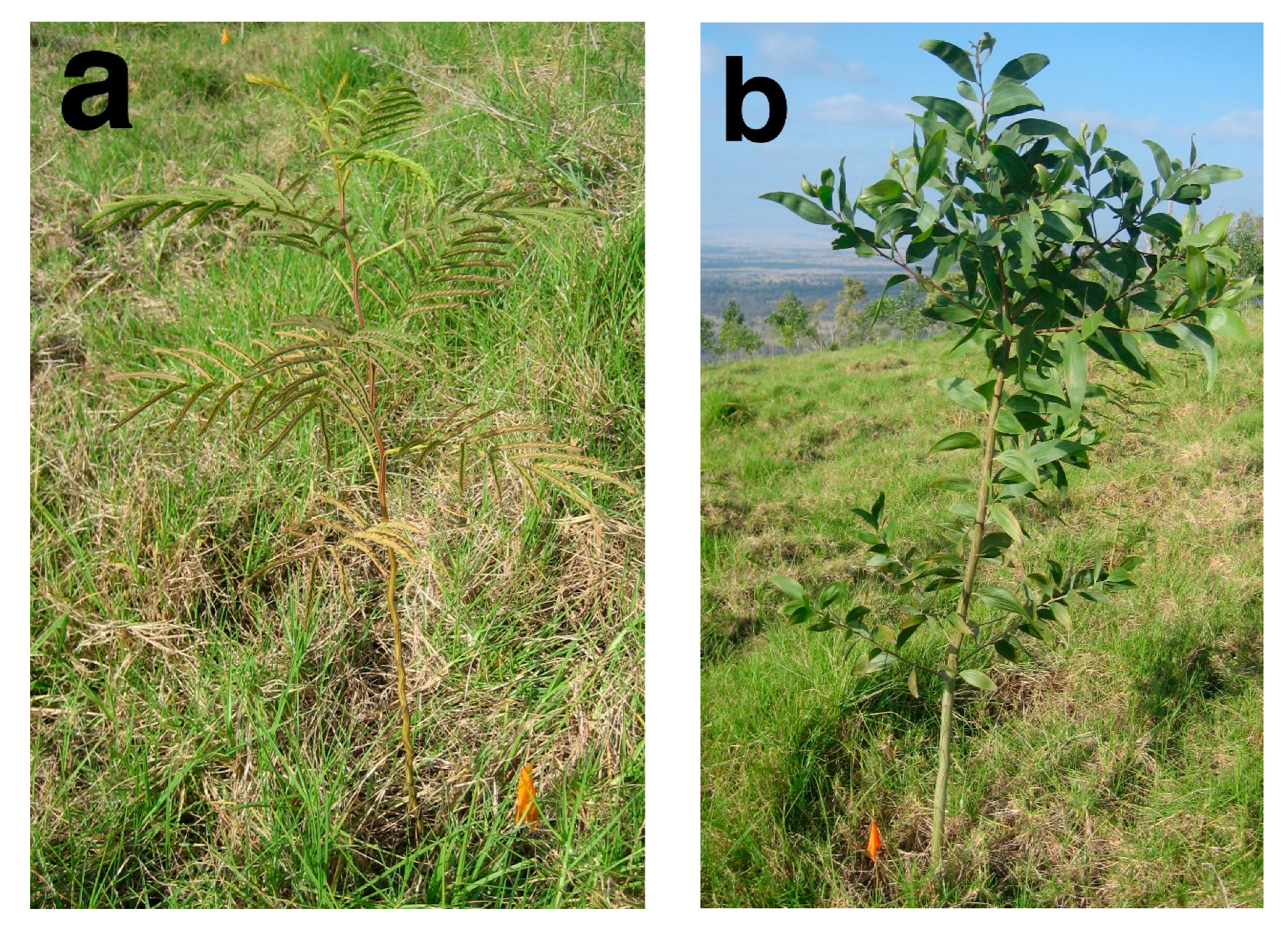

3.2. Phyllode Development

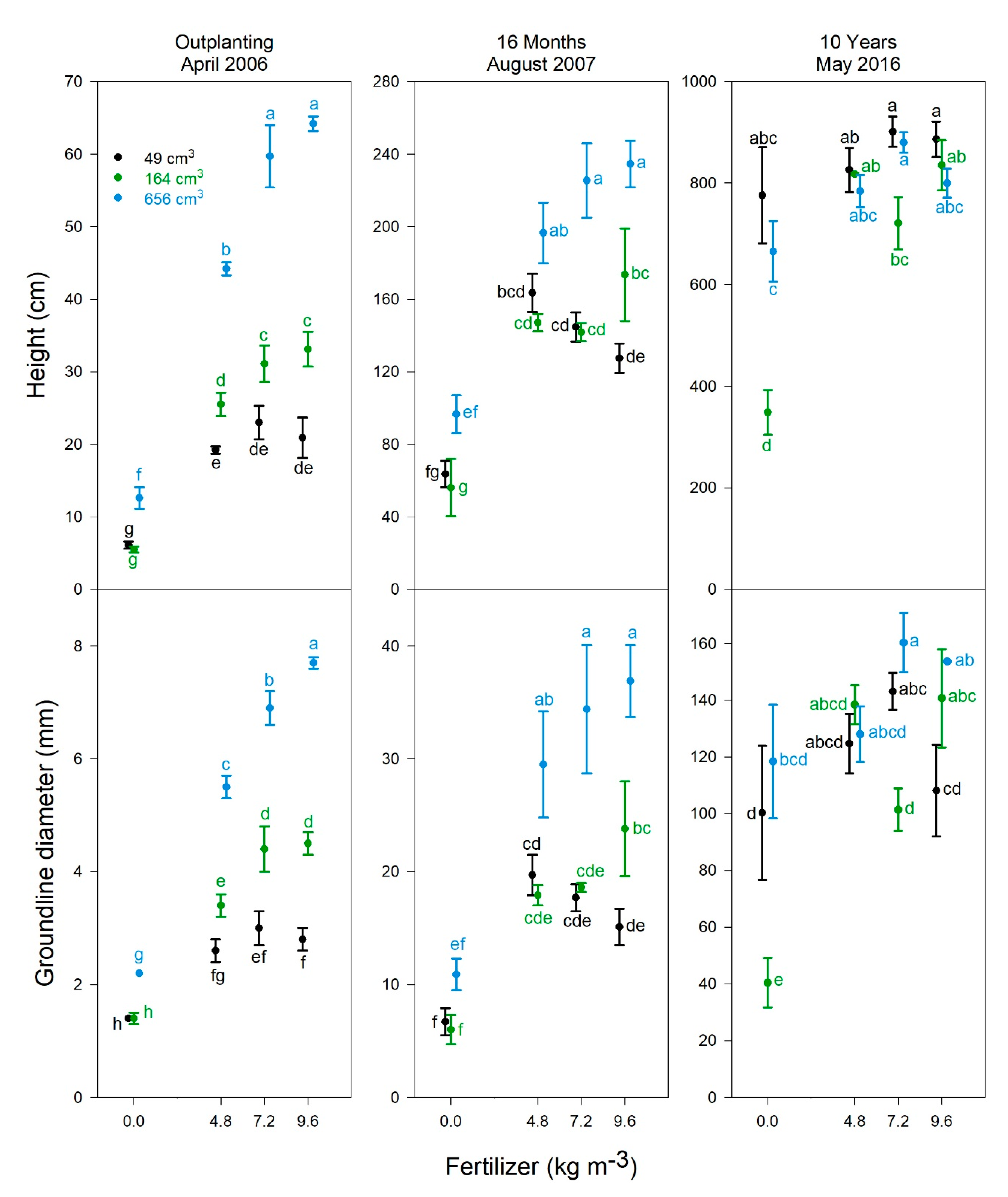

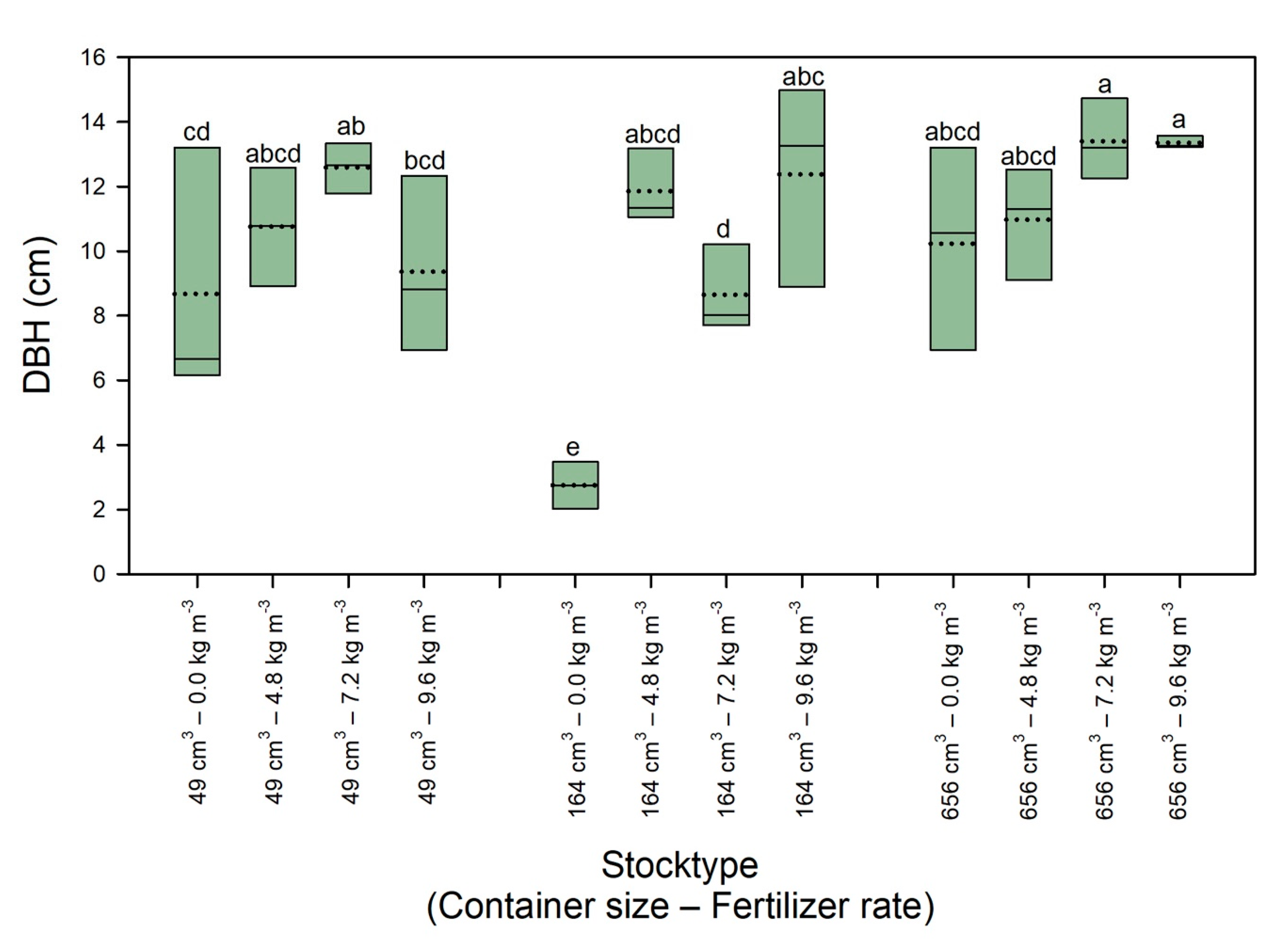

3.3. Tree Growth

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rudel, T.K.; Defries, R.; Asner, G.P.; Laurance, W.F. Changing drivers of deforestation and new opportunities for conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 1396–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houghton, R.A. Carbon emissions and the drivers of deforestation and forest de- gradation in the tropics. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2012, 4, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayas, J.M.R.; Martins, A.; Nicolau, J.M.; Schulz, J.J. Abandonment of agricultural land: An overview of drivers and consequences. CAB Rev. Perspect. Agric. Vet. Sci. Nutr. Nat. Resour. 2007, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cramer, V.A.; Hobbs, R.J.; Standish, R.J. What’s new about old fields? Land abandonment and ecosystem assembly. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 23, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aide, T.M.; Ruiz-Jaen, M.C.; Grau, H.R. What is the state of tropical montane cloud forest restoration? Tropical montane cloud forests. Sci. Conserv. Manag. 2010, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaxton, J.M.; Cordell, S.; Cabin, R.J.; Sandquist, D.R. Non-native grass removal and shade increase soil moisture and seedling performance during Hawaiian dry forest restoration. Restor. Ecol. 2012, 20, 475–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.R.; Davis, A.S.; Leary, J.J.K.; Aghai, M.M. Stocktype and grass suppression accelerate the restoration trajectory of Acacia koa in Hawaiian montane ecosystems. New For. 2015, 46, 855–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelenik, S.G. Linking dominant Hawaiian tree species to understory development in recovering pastures via impacts on soils and litter. Restor. Ecol. 2017, 25, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, P.M.; D’antonio, C.M.; Loope, L.L.; Rejmanek, M.; Westbrooks, R. Introduced species: A significant component of human-caused global change. N. Z. J. Ecol. 1997, 21, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, M.L.; D’antonio, C.M.; Richardson, D.M.; Grace, J.B.; Keeley, J.E.; DiTomaso, J.M.; Hobbs, R.J.; Pellant, M.; Pyke, D. Effects of invasive alien plants on fire regimes. Bioscience 2004, 54, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rose, R.; Carlson, W.C.; Morgan, P. The Target Seedling Concept. In Proceedings of the Combined Meeting of the Western Forest Nursery Associations, Roseburg, OR, USA, 13–17 August 1990; General Technical Report RM-200. Rose, R., Carlson, W.C., Landis, T.D., Eds.; USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, T.D.; Dumroese, R.K. Applying the Target Plant Concept to Nursery Stock Quality. In Plant Quality: A Key to Success in Forest Establishment, Proceedings of the COFORD Conference, Tullow, Ireland, 20–21 September 2005; MacLennan, L., Fennessy, J., Eds.; National Council for Forest Research and Development: Dublin, Ireland, 2006; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Dumroese, R.K.; Landis, T.D.; Pinto, J.R.; Haase, D.L.; Wilkinson, K.M.; Davis, A.S. Meeting forest restoration challenges: Using the Target Plant Concept. Reforesta 2016, 1, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rose, R.; Ketchum, J.S.; Hanson, D.E. Three-year survival and growth of Douglas-fir seedlings under various vegetation-free regimes. For. Sci. 1999, 45, 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Löf, M.; Dey, D.C.; Navarro, R.M.; Jacobs, D.F. Mechanical site preparation for forest restoration. New For. 2012, 43, 825–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chirino, E.; Vilagrosa, A.; Hernández, E.I.; Matos, A.; Vallejo, V.R. Effects of a deep container on morpho-functional characteristics and root colonization in Quercus suber L. seedlings for reforestation in Mediterranean climate. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 256, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Salvador, P.; Puértolas, J.; Cuesta, B.; Peñuelas, J.L.; Uscola, M.; Heredia-Guerrero, N.; Rey Benayas, J.M. Increase in size and nitrogen concentration enhances seedling survival in Mediterranean plantations. Insights from an ecophysiological conceptual model of plant survival. New For. 2012, 43, 755–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overton, W.S.; Ching, K.K. Analysis of differences in height growth among populations in a nursery selection study of Douglas-fir. For. Sci. 1978, 24, 497–509. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, M.; Cole, E.C.; White, D.E. Tall planting stock for enhanced growth and domination of brush in the Douglas-fir region. New For. 1993, 7, 107–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobidon, R.; Charette, L.; Bernier, P.Y. Initial size and competing vegetation effects on water stress and growth of Picea mariana (Mill.) BSP seedlings planted in three different environments. For. Ecol. Manag. 1998, 103, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, D.B.; Mitchell, R.J. Determining the “optimum” slash pine seedling size for use with four levels of vegetation management on a flatwoods site in Georgia, USA. Can. J. For. Res. 1999, 29, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiffault, N.; Jobidon, R.; Munson, A.D. Performance and physiology of large containerized and bare-root spruce seedlings in relation to scarification and competition in Quebec (Canada). Ann. For. Sci. 2003, 60, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rose, R.; Haase, D.L.; Kroiher, F.; Sabin, T. Root volume and growth of ponderosa pine and Douglas-fir seedlings: A summary of eight growing seasons. West. J. Appl. For. 1997, 12, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jacobs, D.F.; Salifu, K.F.; Seifert, J.R. Relative contribution of initial root and shoot morphology in predicting field performance of hardwood seedlings. New For. 2005, 30, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cregg, B.M. Carbon allocation, gas exchange, and needle morphology of Pinus ponderosa genotypes known to differ in growth and survival under imposed drought. Tree Physiol. 1994, 14, 883–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jacobs, D.F.; Salifu, K.F.; Davis, A.S. Drought susceptibility and recovery of transplanted Quercus rubra seedlings in relation to root system morphology. Ann. For. Sci. 2009, 66, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Timmer, V.R.; Miller, B.D. Effects of contrasting fertilization and moisture regimes on biomass, nutrients, and water relations of container grown red pine seedlings. New For. 1991, 5, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.L.; Rose, R.; Trobaugh, J. Field performance of three stock sizes of Douglas-fir container seedlings grown with slow-release fertilizer in the nursery growing medium. New For. 2006, 31, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salifu, K.F.; Jacobs, D.F. Characterizing fertility targets and multi-element interactions in nursery culture of Quercus rubra seedlings. Ann. For. Sci. 2006, 63, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uscola, M.; Salifu, K.F.; Oliet, J.A.; Jacobs, D.F. An exponential fertilization dose response model to promote restoration of the Mediterranean oak Quercus ilex. New For. 2015, 46, 795–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Endean, F.; Carlson, L.W. The effect of rooting volume on the early growth of lodgepole pine seedlings. Can. J. For. Res. 1975, 5, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamhamedi, M.S.; Bernier, P.Y.; Hébert, C. Effect of shoot size on the gas exchange and growth of containerized Picea mariana seedlings under different watering regimes. New For. 1996, 13, 207–221. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, J.R.; Dumroese, R.K.; Davis, A.S.; Landis, T.D. Conducting seedling stocktype trials: A new approach to an old question. J. For. 2011, 109, 293–299. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan, J.L.; Burney, O.T.; Pinto, J.R. Drought-conditioning of quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx.) seedlings during nursery production modifies seedling anatomy and physiology. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 557894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.S.; Jacobs, D.F. Quantifying root system quality of nursery seedlings and relationship to outplanting performance. New For. 2005, 30, 295–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.C.; Jacobs, D.F. Quality assessment of temperate zone deciduous hardwood seedlings. New For. 2006, 31, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balis-Larsen, M.; Motivansm, K. Saving species on the brink of extinction. Endanger. Species Bull. 2003, 28, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, W.L.; Herbst, D.R.; Sohmer, S.H. Manual of the Flowering Plants of Hawaii; Bishop Museum: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1990; Volume 1, p. 988. [Google Scholar]

- Selmants, P.C.; Giardina, C.P.; Jacobi, J.D.; Zhu, Z. Chapter 2: Baseline Land Cover. In Baseline and Projected Future Carbon Storage and Carbon Fluxes in Ecosystems of Hawai‘I; Geological Survey Professional Paper 1834; U.S. Department of the Interior: Washington, DC, USA; U.S. Geological Survey: Reston, VA, USA, 2017; pp. 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Friday, J.B.; Cordell, S.; Giardina, C.P.; Inman-Narahari, F.; Koch, N.; Leary, J.J.K.; Litton, C.M.; Trauernicht, C. Future directions for forest restoration in Hawaii. New For. 2015, 46, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanturf, J.A.; Palik, B.J.; Dumroese, R.K. Contemporary forest restoration: A review emphasizing function. For. Ecol. Manag. 2014, 331, 292–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scowcroft, P.G.; Jeffrey, J. Potential significance of frost, topographic relief, and Acacia koa stands to restoration of mesic Hawaiian forests on abandoned rangeland. For. Ecol. Manag. 1999, 114, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.M.; Mountainspring, S.; Ramsey, F.L.; Kepler, C.B. Forest bird communities of the Hawaiian Islands: Their dynamics, ecology, and conservation. Stud. Avian Biol. 1986, 9, 1–431. [Google Scholar]

- Maxfield, B. Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge. Endanger. Species Bull. 2003, 28, 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yanagida, J.F.; Friday, J.B.; Illukpitiya, P.; Mamiit, R.J.; Edwards, Q. Economic value of Hawai‘i’s forest industry in 2001. Econ. Issues 2004, 7, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Elevitch, C.R.; Wilkinson, K.M.; Friday, J.B. Acacia koa (koa) and Acacia koaia (koai’a). In Traditional Trees of Pacific Islands: Their Culture, Environment, and Use; Elevitch, C.R., Ed.; Permanent Agriculture Resources: Holualoa, HI, USA, 2006; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Lowell, E.C.; Wilson, K.; Friday, J.B.; Wiedenbeck, J.; Chan, C. Market appeal of Hawaiian koa wood product characteristics: A consumer preference study. In Proceedings of the 59th International Convention of Society of Wood Science and Technology, Curitiba, Brazil, 6–10 March 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, T.G.; Yost, R.S.; Kablan, R.; Olsen, T. Growth potential of twelve Acacia species on acid soils in Hawaii. For. Ecol. Manag. 1996, 80, 175–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.M.E.; Friday, J.B.; Oliet, J.A.; Jacobs, D.F. Canopy openness affects microclimate and performance of underplanted trees in restoration of high-elevation tropical pasturelands. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 292, 108105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrotta, J.A. The role of plantation forests in rehabilitating degraded tropical ecosystems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 1992, 41, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horiuchi, B.; Jeffrey, J. Native Plant Propagation and Habitat Restoration at Hakalau Forest NWR, Hawai’i. In National Proceedings: Forest and Conservation Nursery Associations—1999, 2000, and 2001, Proceedings RMRS-P-24, Kailua-Kona, USA, 22-25 August 2000; Dumroese, R.K., Riley, L.E., Landis, T.D., Eds.; USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2002; p. 233. [Google Scholar]

- Pejchar, L.; Press, D.M. Achieving conservation objectives through production forestry: The case of Acacia koa on Hawaii Island. Environ. Sci. Policy 2006, 9, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motooka, P.; Castro, L.; Nelson, D.; Nagai, G.; Ching, L. Weeds of Hawai‘i’s Pastures and Natural Areas; University of Hawai’i, Manoa: Manoa, HI, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Shlisky, A. The Hawaiian Island environment. Rangel Arch 2000, 22, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jeffery, J.; Horicuhi, B. Tree planting at Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge—The right tool for the right stock type. Nativ. Plants J. 2003, 4, 30–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scowcroft, P.G.; Adee, K.T. Site Preparation Affects Survival, Growth of Koa on Degraded Montane Forest Land; Research Paper PSW-205; USDA Forest Service Pacific Southwest Research Station: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1991.

- Davis, A.S.; Pinto, J.R.; Jacobs, D.F. Early field performance of Acacia koa seedlings grown under subirrigation and overhead irrigation. Nativ. Plants J. 2011, 12, 94–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumroese, R.K.; Jacobs, D.F.; Davis, A.S. Inoculating Acacia koa with Bradyrhizobium and applying fertilizer in the nursery: Effects on nodule formation and seedling growth. Hort Sci. 2009, 44, 443–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dumroese, R.K.; Davis, A.S.; Jacobs, D.F. Nursery response of Acacia koa seedlings to container size, irrigation method, and fertilization rate. J. Plant Nutr. 2011, 34, 877–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idol, T.W.; Diarra, G. Mycorrhizal colonization is compatible with exponential fertilization to improve tree seedling quality. J. Plant Nutr. 2016, 40, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earnshaw, K.M.; Baribault, T.W.; Jacobs, D.F. Alternative field fertilization techniques to promote restoration of leguminous Acacia koa on contrasting tropical sites. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 376, 126–134. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, K.M.E.; Friday, J.B.; Jacobs, D.F. Establishment and heteroblasty of Acacia koa in canopy gaps. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 453, 117592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.M.E.; Mickelbart, M.V.; Jacobs, D.F. Plasticity of phenotype and heteroblasty in contrasting populations of Acacia koa. Ann. Bot. 2019, 124, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, G.A.; Bartholomew, D.P. Acacia koa leaves and phyllodes: Gas exchange, morphological, anatomical, and biochemical characteristics. Bot. Gaz. 1984, 145, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, G.A.; Bartholomew, D.P. Adaptation of Acacia koa leaves and phyllodes to changes in photosynthetic photon flux density. For. Sci. 1990, 36, 1050–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, D.H. Water relations of compound leaves and phyllodes in Acacia koa var. latifolia. Plant Cell Environ. 1986, 9, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, D.H. Establishment and persistence characteristics in juvenile leaves and phyllodes of Acacia koa (Leguminosae) in Hawaii. Int. J. Plant Sci. 1996, 157, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craven, D.; Gulamhussein, S.; Berlyn, G.P. Physiological and anatomical responses of Acacia koa (Gray) seedlings to varying light and drought conditions. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2010, 69, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquet-Kok, J.; Creese, C.; Sack, L. Turning over a new ‘leaf’: Multiple functional significances of leaves versus phyllodes in Hawaiian Acacia koa. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 2084–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giffin, J.G. Puu Waawaa Biological Assessment. Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State of Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources. 2003. Available online: http://dlnr.hawaii.gov/dofaw/files/2014/02/PWW_biol_assessment.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2020).

- Soil Survey Staff. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. Official Soil Series Descriptions. 2020. Available online: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/soils/survey/ (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- Baker, P.J.; Scowcroft, P.G.; Ewel, J.J. Koa (Acacia koa) Ecology and Silviculture; US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station: Albany, CA, USA, 2009; 129p.

- Giambelluca, T.W.; Chen, Q.; Frazier, A.G.; Price, J.P.; Chen, Y.-L.; Chu, P.-S.; Eischeid, J.K.; Delparte, D.M. Online Rainfall Atlas of Hawai’i. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2013, 94, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, D.B. Relative growth rates: A critique. South Afr. For. J. 1995, 173, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.R.; Marshall, J.D.; Dumroese, R.K.; Davis, A.S.; Cobos, D.R. Photosynthetic response, carbon isotopic composition, survival, and growth of three stock types under water stress enhanced by vegetative competition. Can. J. For. Res. 2012, 42, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuesta, B.; Villar-Salvador, P.; Puértolas, J.; Jacobs, D.F.; Benayas, J.M.R. Why do large, nitrogen rich seedlings better resist stressful transplanting conditions? A physiological analysis in two functionally contrasting Mediterranean forest species. For. Ecol. Manag. 2010, 260, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holl, K.D.; Loik, M.E.; Lin, E.H.V.; Samuels, I.A. Tropical montane forest restoration in Costa Rica: Overcoming barriers to dispersal and establishment. Restor. Ecol. 2000, 8, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabin, R.J.; Weller, S.G.; Lorence, D.H.; Cordell, S.; Hadway, L.J. Effects of microsite, water, weeding, and direct seeding on the regeneration of native and alien species within a Hawaiian dry forest preserve. Biol. Conserv. 2002, 104, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denslow, J.S.; Uowolo, A.L.; Hughes, R.F. Limitations to seedling establishment in a mesic Hawaiian forest. Oecologia 2006, 148, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiffault, N.; Roy, V. Living without herbicides in Québec (Canada): Historical context, current strategy, research and challenges in forest vegetation management. Eur. J. For. Res. 2011, 130, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, D.B.; Rose, R.W.; McNabb, K.L. Nursery and site preparation interaction research in the United States. New For. 2001, 22, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar-Salvador, P.; Uscola, M.; Jacobs, D.F. The role of stored carbohydrates and nitrogen in the growth and stress tolerance of planted forest trees. New For. 2015, 46, 813–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scowcroft, P.G.; Haraguchi, J.E.; Hue, N.V. Reforestation and topography affect montane soil properties, nitrogen pools, and nitrogen transformations in Hawaii. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2004, 68, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idol, T.W.; Baker, P.J.; Meason, D.F. Indicators of forest ecosystem productivity and nutrient status across precipitation and temperature gradients in Hawaii. J. Trop. Ecol. 2007, 23, 693–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Dumroese, R.K.; Pinto, J.R. Organic or inorganic nitrogen and rhizobia inoculation provide synergistic growth response of a leguminous forb and tree. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Q.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Dumroese, R.K. Interaction of biochar type and rhizobia inoculation increases the growth and biological nitrogen fixation of Robinia pseudoacacia seedlings. Forests 2020, 11, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliet, J.A.; Jacobs, D.F. Restoring forests: Advances in techniques and theory. New For. 2012, 43, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D.F.; Oliet, J.A.; Aronson, J.; Bolte, A.; Bullock, J.M.; Donoso, P.J.; Landhäusser, S.M.; Madsen, P.; Peng, S.; Rey-Benayas, J.M.; et al. Restoring forests: What constitutes success in the twenty-first century? New For. 2015, 46, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löf, M.; Madsen, P.; Metslaid, M.; Witzell, J.; Jacobs, D.F. Restoring forests: Regeneration and ecosystem function for the future. New For. 2019, 50, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Whitesell, C.D. Acacia koa A. Gray. In Silvics of North America. Volume 2: Hardwoods; Burns, R.M., Honkala, B.H., Eds.; Agricultural Handbook 654; USDA Forest Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1990; pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Oliet, J.A.; Artero, F.; Cuadros, S.; Puértolas, J.; Luna, L.; Grau, J.M. Deep planting with shelters improves performance of different stocktype sizes under arid Mediterranean conditions. New For. 2012, 43, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghai, M.M.; Pinto, J.R.; Davis, A.S. Container volume and growing density influence western larch (Larix occidentalis Nutt.) seedling development during nursery culture and establishment. New For. 2014, 45, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, B.; Maltoni, A.; Chiarabaglio, P.M.; Giorcelli, A.; Jacobs, D.F.; Tognetti, R.; Tani, A. Can the use of large, alternative nursery containers aid in field establishment of Juglans regia and Quercus robur seedlings? New For. 2015, 46, 773–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdett, A.N. Physiological processes in plantation establishment and the development of specifications for forest planting stock. Can. J. For. Res. 1990, 20, 415–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossnickle, S.C. Importance of root growth in overcoming planting stress. New For. 2005, 30, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galloway, G.; Ugalde, L.; Vasquez, W. Importance of density reductions in tropical plantations: Experiences in Central America. For. Trees Livelihoods 2001, 11, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotto, D.; Montagnini, F.; Ugalde, L.; Kanninen, M. Growth and effects of thinning of mixed and pure plantations with native trees in humid tropical Costa Rica. For. Ecol. Manag. 2003, 177, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scowcroft, P.G.; Stein, J.D. Stimulating Growth of Stagnated Acacia koa by Thinning and Fertilizing; Research Note PSW-380; USDA Forest Service Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1986; p. 8.

- Pearson, H.L.; Vitousek, P.M. Stand dynamics, nitrogen accumulation, and symbiotic nitrogen fixation in regenerating stands of Acacia koa. Ecol. Appl. 2001, 11, 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idol, T.W.; Morales, R.M.; Friday, J.B.; Scowcroft, P.G. Precommercial release thinning of potential Acacia koa crop trees increases stem and crown growth in dense, 8-year-old stands in Hawaii. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 392, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haggar, J.P.; Briscoe, C.B.; Butterfield, R.P. Native species: A resource for the diversification of forestry production in the lowland humid tropics. For. Ecol. Manag. 1998, 106, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jacobs, D.F.; Davis, A.S.; Dumroese, R.K.; Burney, O.T. Nursery Cultural Techniques Facilitate Restoration of Acacia koa Competing with Invasive Grass in a Dry Tropical Forest. Forests 2020, 11, 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11111124

Jacobs DF, Davis AS, Dumroese RK, Burney OT. Nursery Cultural Techniques Facilitate Restoration of Acacia koa Competing with Invasive Grass in a Dry Tropical Forest. Forests. 2020; 11(11):1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11111124

Chicago/Turabian StyleJacobs, Douglass F., Anthony S. Davis, R. Kasten Dumroese, and Owen T. Burney. 2020. "Nursery Cultural Techniques Facilitate Restoration of Acacia koa Competing with Invasive Grass in a Dry Tropical Forest" Forests 11, no. 11: 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11111124

APA StyleJacobs, D. F., Davis, A. S., Dumroese, R. K., & Burney, O. T. (2020). Nursery Cultural Techniques Facilitate Restoration of Acacia koa Competing with Invasive Grass in a Dry Tropical Forest. Forests, 11(11), 1124. https://doi.org/10.3390/f11111124