Abstract

In this paper, we consider the following sliding puzzle called torus puzzle. In an m by n board, there are pieces numbered from 1 to . Initially, the pieces are placed in ascending order. Then they are scrambled by rotating the rows and columns without the player’s knowledge. The objective of the torus puzzle is to rearrange the pieces in ascending order by rotating the rows and columns. We provide a solution to this puzzle. In addition, we provide lower and upper bounds on the number of steps for solving the puzzle. Moreover, we consider a variant of the torus puzzle in which each piece is colored either black or white, and we present a hardness result for solving it.

1. Introduction

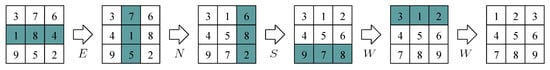

In this paper, we address m by n torus puzzle which is similar to sliding puzzles such as the 15 puzzle. The torus puzzle consists of pieces numbered from 1 to , and the pieces are placed on a board of m rows by n columns. Initially, for each , the piece numbered r is placed at the pth row and qth column, where and . In the puzzle, there are four basic operations, N, S, E, and W (these stand for north, south, east and west). The N (respectively, S) operation shifts the pieces in a column upward (respectively, downward). That is, by applying the N (respectively, S) operation to a column , is changed into (respectively, ), where denotes the transpose of a matrix . Similarly, the E (respectively, W) operation rotates a row into (respectively, ). After performing a sequence of the basic operations, the configuration of the board would differ considerably from the initial configuration. The objective of the torus puzzle is to restore the initial configuration from the scrambled configuration (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

An example of play.

Although the 15 puzzle can be intuitively modified into the torus puzzle, the torus puzzle is relatively less popular. This is possibly because it is not easy to implement the torus puzzle on a board, unlike the 15 puzzle. However, the torus puzzle is now gaining popularity owing to the proliferation of touch-panel devices. In fact, the torus puzzle has already been implemented as an application called RotSquare on Mac OS (and is now an iPhone app).

The torus puzzle has not been investigated extensively thus far. In Section 4 in [1], the number of steps for randomizing the configurations of an n by n board is discussed. In [2], it is shown that an n by n board for every even number n, any configuration can be obtained from the initial configuration by showing that any two adjacent pieces can be reversed without disturbing the positions of the others. In this paper, we study the complexity of solving the torus puzzle (and its variant). The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 is devoted to a solution of the torus puzzle. After introducing some definitions and notations, we provide the basic tools for solving the torus puzzle, and then we show how the torus puzzle is solved with the basic tools. In Section 3, we discuss the upper and lower bounds on the number of “steps” for obtaining the initial configuration from a scrambled configuration, where successive identical operations applied to a row/column, such as for some row , are counted as one step. This form of counting is intuitive when the torus puzzle is implemented on a touch-panel device. The lower bound can be obtained by a standard argument. In Section 4, we consider a variant of the torus puzzle in which the pieces are colored white or black. For the variant, we address the hardness in estimating the minimum number of steps for reaching a given goal configuration from a given start configuration. Unfortunately, we have not determined the hardness for the torus puzzle thus far (it is known that finding the shortest solution for an extension of the 15 puzzle is NP-hard [3]).

2. Preliminary

In this section, first we give some definitions and notation, then provide basic tools to solve the torus puzzle, and finally show how to solve the torus puzzle with the basic tools.

2.1. Definitions and Notation

This subsection introduces definitions, notation, and conventions. Let O be an operation in . We denote by the execution of i consecutive O operations on , where is a row (respectively, column) of the board if (respectively, ). We simply write as . We call for some i and (respectively, ) a row (respectively, column) operation. It is easy to see that (respectively, ) is the same action as (respectively, ).

In this paper, a configuration means a placement of the pieces on the board. We will refer to the following configuration as initial configuration and denote it by : the piece numbered is placed at the ith row and the jth column for each and . There are two ways to refer a piece in a configuration. One is by its number and the other is by its position on the board: The piece having number r is referred to as “the piece numbered r”, and the piece placed at the ith row and the jth column in a configuration is called “the piece placed at ” in the configuration.

Let denote the set of configurations of the m by n board (a configuration of the board can be considered as an m by n matrix in which the pieces are numbered bijectively from ). We say that the board has a configuration if the piece placed at has number r iff for each and . The symbol (respectively, ) is used to refer to the kth row (respectively, column). We say that the piece numbered r is at its right position in if , where and . For , , we write , or simply , if can be obtained from by performing a sequence of the basic operations . We thus also write , or simply , if there is no sequence of the basic operations such that can be obtained from by applying .

Let be a sequence of the basic operations, where for and we are assuming that . The integer ℓ and the value are referred to as drag number and push number of the sequence , respectively. We denote the drag and push numbers of by and , respectively. For configurations and , we denote the values and by and , respectively, where both minimums are taken over all sequences deriving from . Specially, in the case where is the initial configuration , we simply write and instead of and . The value and are both natural values to measure how far is from the initial configuration . In a situation where the torus puzzle is implemented on a touch-panel device, it would be natural to consider a consecutive iterations of the same operation as a single step. In this paper, we use , that is, for each is counted as one step, not k steps.

2.2. A Basic Tool: Three Elements Rotations

In this section, we introduce a basic tool called three elements rotation, which plays a fundamental role in the solution.

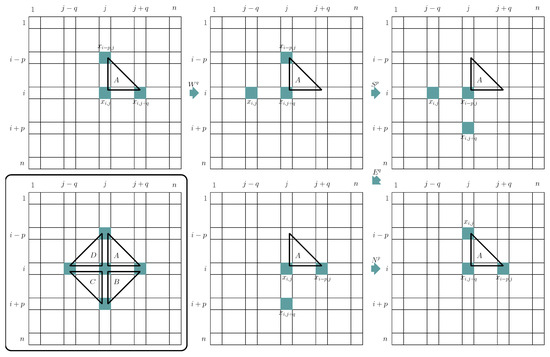

Consider the the following eight patterns of four consecutive operations. Figure 2 is used for showing how the eight patterns work. In Figure 2, there are five points: (the ith row, the jth column), (the th row, the jth column), (the ith row, the th column), and there are four triangles consisting of three of these points: A, B, C, and D. It is a routine to check that each pattern makes a clockwise or counterclockwise rotation of the three corners of a triangle A, B, C, or D without other changes of piece positions.

Figure 2.

The eight rotations.

- 1.

- , , , → clockwise on A,

- 2.

- , , , → counterclockwise on A,

- 3.

- , , , → clockwise on B,

- 4.

- , , , → counterclockwise on B,

- 5.

- , , , → clockwise on C,

- 6.

- , , , → counterclockwise on C,

- 7.

- , , , → clockwise on D,

- 8.

- , , , → counterclockwise on D.

These patterns are referred to as “triangle rotations”.

By combining two triangle rotations, a useful rotation can be built as follows. Let be a configuration in . Let be the configuration obtained from by applying basic operations to the board in the following order: , , , , , , for and (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Three elements rotation.

It is easy to see that the only difference between and is the ith row, and the ith row in is:

That is, only the part of the ith row is changed (rotated) into . We will refer to this change as three elements rotation on (, p, q, west) (the east version can be defined similarly). Specially, we denote the three elements rotation on (, 1, 1, west) by (the corresponding east version is denoted by ). For example, results in .

2.3. Solution

In this section, we show how to solve the torus puzzle by considering the two cases where is even and is odd. Not surprisingly, there is a difference between the even case and the odd case. In the even case, for any , can be changed into the initial configuration by applying a sequence of the basic operations. But this is not true for the odd case. (A similar thing happened for the 15 puzzle [4].) To describe our solution of the torus puzzle, we need the following lemmas.

Lemma 1.

Suppose that is an even integer. For any two consecutive pieces and in a row of a configuration , we can swap the positions of two pieces without causing any other change of position by applying a sequence of basic operations. More precisely, it holds that , where , , and for .

Proof.

Suppose (the case of is trivial). It is sufficient to show that there is a sequence of basic operations which changes the first row into . Apply , , , , in this order, then the first row becomes . Finally, execute , then we have the desired result. □

The next lemma is inspired by an argument on the parity of permutations in [4].

Lemma 2.

Suppose that is an odd integer. For any two consecutive pieces and in a row of a configuration , we cannot swap the positions of two pieces without causing any other change of position. More precisely, it holds that , where , , and for .

Proof.

Suppose not, then there is a sequence of basic operations which swaps the positions. Let h (respectively, v) be the number of row (respectively, column) operations in , Then, has h permutations of n elements and v permutations of m elements (i.e., h cycles of length n and v cycles of length m). As any permutation of elements can be represented by the production of transpositions, can be represented with transpositions. This, however, means that is even permutation, since both and are even. However, should be odd permutation, a contradiction. □

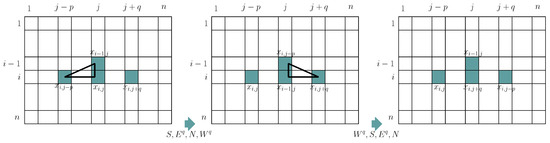

We are now ready to demonstrate our solution. Let be the initial configuration. We first show how to obtain a configuration from any configuration such that for , , i.e., achieves the initial configuration except for the bottom row. Suppose that the pieces numbered 1, , are already at their right positions. Let p and q be the integers such that and . We now wish to have a configuration in which the pieces numbered 1, , r are at their right positions. Let be the position of the piece numbered r in the current configuration. We will refer to the outside of the region placed the pieces numbered 1, , as work space. By proper choice of a third corner (from work space) and executing a proper triangle rotation on the three corners , , and , we can have the desired configuration. Note that, because of the work space, we can take a third corner properly (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Work space and third corner

We now show how to achieve the initial configuration from the configuration . First, consider the case where is even. Without loss of generality, we may assume that n is even. Since the case of is easy, we assume . By applying three elements rotation as many times as necessary, the piece numbered can be replaced at its right position . We repeat this process for pieces numbered , , . By Lemma 1, we can swap the positions of pieces numbered and if necessary (i.e., if the last row is . Then, we have the initial configuration .

Now consider the case where is odd. In a similar fashion as above, the last row in can be changed into by applying three elements rotation as many times as necessary. If we assume that (i.e., ), then, by Lemma 2, it is impossible to be . Thus, should be , which means that we have already had the desired result.

3. Upper and Lower Bounds of diam

In this section, we consider the following problem: How many steps are enough to derive a configuration from a configuration . That is, we try to evaluate the value . We call the value the diameter of and denote it by diam. Next theorem gives simple upper and lower bounds for diam. (For pebble games which are generalization of the 15 puzzle, a similar study can be found in [5].)

Theorem 1.

The following statements hold:

- 1.

- For any configurations , with , for some constant c.

- 2.

- For a given , there are integers m and n such that for any configuration there is a configurations for which .

Proof.

We first show the first statement. Since triangle rotation and three elements rotation take four and seven steps, respectively, according to our solution described in the previous section, we can have an upper bound: diam for some constant c.

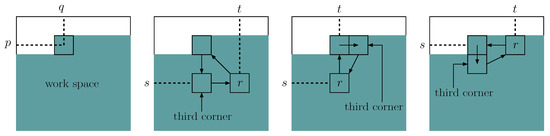

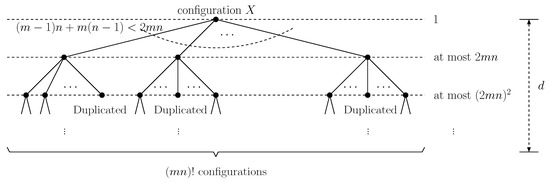

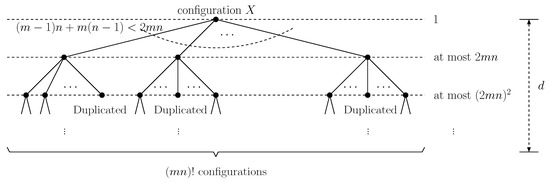

We now show the second statement. Let us consider first the case where is even. Note that . For a configuration in , let denote the set of configurations obtained from by executing one row or column operation (namely, can be obtained from by applying for and some integer k). Let . Since is at most , is at most (see Figure 5). Hence, as , holds. Since , it follows that . This completes the proof of the even case for the second statement.

Figure 5.

The relation between d and .

Let us consider now the case where is odd. The second statement holds also for the odd case. This can be proved by the almost same way. The difference is the number of configurations obtained from , that is, holds for the odd case. Clearly, the difference does not affect the result of calculation. □

By applying a similar argument to evaluating the push number, we have that is for any pair with , and for any there is such that is .

4. Hardness

In this section, we consider a variant of the torus puzzle in which the pieces are colored with white or black. The end of the variant is to derive from a given start configuration to a given goal configuration. For the variant, we show that the following problem is NP-hard by reduction from 3-PARTITION: For given a start configuration , a goal configuration , and an integer k, whether or not ? We will refer to this problem as BWP (Black & White Problem).

3-PARTITION

- INSTANCE:

- A bound , a set , , of positive integers such that for each , and .

- QUESTION:

- Can A be partitioned into m disjoint sets , , such that for each ?

Since 3-PARTITION is strongly NP-complete [6], without loss of generality we can assume that each is given in unary representation.

Observation 1.

Let be a row in the board. If has i black pieces, then, in order to make so that has black pieces, at least j column operations are needed. This is because that each column operation remove at most one black piece from . For the same reason (just thought black piece as white and vice versa), if has i black pieces, then in order to make so that has black pieces, at least j column operations are needed. The same holds true for a column.

Theorem 2.

BWP is NP-hard.

Proof.

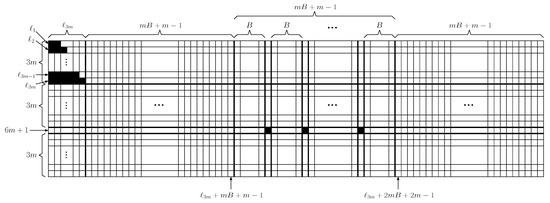

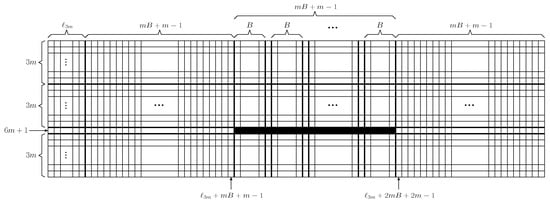

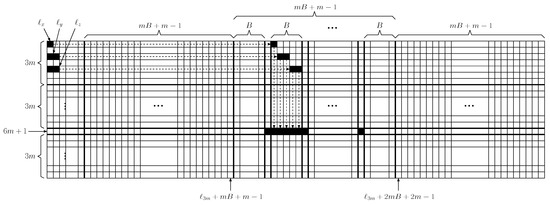

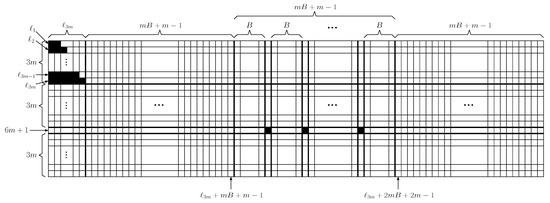

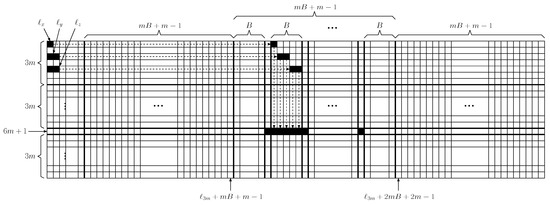

For given an instance of 3-PARTITION, we construct an instance of BWP as follows: The start and goal configurations are illustrated in Figure 6 and Figure 7 and . Without loss of generality, we may assume . The board in has rows, columns, and black pieces. The th row plays an important role in this proof. As we shall show later, the black pieces in the th row in the start configuration cannot move both horizontally and vertically. The other black pieces initially placed at the upper left in the start configuration will be replaced in the th row in the goal configuration.

Figure 6.

Start configuration.

Figure 7.

Goal configuration.

Let be a sequence of row and column operations such that derives the goal configuration from the start configuration. Let be the set of configurations which appear during the steps derived by .

[ is a yes instance ⇒ is a yes instance.]

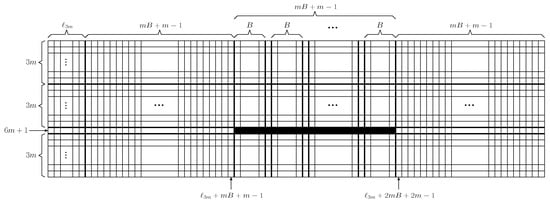

Since is a yes instance, there are m disjoint sets , , such that for each . For each , first shift the black pieces corresponding , , horizontally as shown in Figure 8. Then shift the black pieces corresponding , , vertically. This can be done with steps. Hence, is a yes instance.

Figure 8.

Procedure of move of the black pieces corresponding .

[ is a yes instance ⇐ is a yes instance.]

Since the first column has black pieces in the start configuration and no black piece in the goal configuration, by Observation 1, has at least row operations. Similarly, as the th row has black pieces in the start configuration and black pieces in the goal configuration, has at least column operations. Thus, as , has exactly row operations and column operations. Hence, each of the row operations should sweep out of a black piece from the first column, and each of column operations should bring a black piece into the th row. Furthermore, once a black piece is in the th row, the piece should be in the row during the steps derived by , since has exactly column operations.

Let , , denote the black pieces in the th row and , , denote the other black pieces in the start configuration. We now give the following claims. Note that each cannot be shifted vertically since a black piece is in the th row cannot swept out from the th row.

Claim 1.

For any configuration , in the th row in , there is no two black pieces at least column away from each other.

Proof.

If not so, there are two black pieces at least column away from each other. Since there are no such black pieces at least column away from each other in the th row in the goal configuration, one of the two pieces should sweep out from the row. This, however, is not allowed as explained above, a contradiction. □

Claim 2.

In , no operation is applied to the first column and also no operation is applied to the th row.

Proof.

We first show that if the first column is shifted vertically at some step, then the th row has been shifted horizontally before that step. Suppose that, in , there is a column operation applied to the first column. Note that, by this column operation, a black piece is placed at . From Claim 1, before applying this operation, (or ) should be already in the jth column for some , where . As each cannot move vertically, (or ) should be moved by a row operation.

On the other hand, to apply a row operation to the th row, the piece placed at should be black, because a black piece in the first column must be swept out from the first column whenever a row operation is executed. However, in order to place a black piece at without applying a row operation to th row, the first column should be shifted vertically, so we have a deadlock. The deadlock completes the proof. □

We next show that each first move horizontally, then move vertically. Let I denote the set of indexes k such that and the kth column in the start configuration has no black piece. Note that . Since has exactly column operations, by Claim 2 (i.e., the th row cannot shift horizontally), in , each column with must be applied exactly one column operation. Similarly, since has exactly row operations, by Claim 2 (i.e., the first column cannot shift vertically), in , each row with must be applied exactly one row operation. Thus, first must move to a column with , then move vertically.

We now claim that in any configuration , each column with has at most one black piece. If not so, there is a column with such that has more than one black piece in a configuration . One of those black pieces must be swept out from by applying a row operation. Let p be such a black piece swept out from . Since p has two row operations, p moves first horizontally, second vertically, then horizontally (Recall that each row , , has exactly one row operation). Let O be the row operation for the second horizontal movement of p, and x the index such that O apply to the xth row . Then, x must be , because p has moved vertically to a row between the th row and the th row. But, since row operations are applicable only to for , p now cannot move horizontally.

As a result, each first move to a column with , then move vertically to . Moreover, in any configuration in , each column with has at most one black piece. This means that , , must be able to partitioned into m groups that all have the same sum B. Therefore, is a yes instance.

5. Discussion

In this paper, we showed that . It would be interesting to improve the lower or upper bounds, especially the lower bound. One way to obtain upper bounds is to find integers p, q, , , b, and a “potential" function satisfying the following conditions: (1) iff (the potential of the initial configuration is zero), (2) with , such that and (if the potential is at least some threshold, say b, then one can decrease it by q using at most steps.), (3) if , then (if the potential is less than b, then we can always reach within steps.), and (4) for every (the maximum potential is p.) This would imply that the upper bound of . Actually, our upper bound was obtained in this manner by setting iff the pieces numbered are placed at their right positions and the piece numbered is not placed at its right position. We believe that our upper bound can still be improved to 3, even if one uses the same . However, we suspect that more sophisticated will be needed to find a better upper bound. On the other hand, our lower bound was obtained by considering the graph It would be interesting to improve the lower bound by using the structural information of G.

It would also be interest to determine diam, even if n is 4 or 5. This is because 4 by 4 or 5 by 5 may be popular sizes when playing the torus puzzle on touch-panel devices. We performed computer experiments on diam for small values of m and n: diam, diam, diam, diam, diam, and diam.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Super Science High School program launched by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. We thank Shin-ichi Nakano, Toru Araki, and Shingo Osawa for helpful discussion.

References

- Diaconis, P. Group Representations in Probability and Statistics. In IMS Lecture Notes-Monograph Series; Institute of Mathematical Statistics: Hayward, CA, USA, 1988; Volume 11. [Google Scholar]

- Bogomolny, A.; Greenwell, D. “Sliders”—Columns Cut the Knot! Available online: http://www.maa.org/editorial/knot/slider.html (accessed on 9 January 2012).

- Ratner, D.; Warmuth, M. The (n2 − 1)-puzzle and related relocation problems. J. Symb. Comput. 1990, 10, 111–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, W.; Story, W. Notes on the “15” Puzzle. Am. J. Math. 1879, 2, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornhauser, D.; Miller, G.; Spirakis, P. Coordinating Pebble Motion On Graphs, The Diameter Of Permutation Groups, and Applications. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science (SFCS ’84), Singer Island, FL, USA, 24–26 October 1984; pp. 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- Garey, M.; Johnson, D. Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness; W. H. Freeman and Company: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2012 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).