1. Introduction

In recent years, diffusion models have emerged as a core technological pillar in the field of generative artificial intelligence due to their exceptional generative capabilities. As a generative paradigm based on progressive denoising, diffusion models synthesize high-quality images that combine remarkable diversity with photorealistic fidelity. They have achieved breakthrough progress in text-to-image (T2I) generation tasks, rapidly becoming a central focus of both academic research and industrial applications. Their powerful content generation capabilities demonstrate broad application prospects and immense potential value across diverse creative domains, including digital art production, advertising design, entertainment media, educational training, and industrial prototyping.

For ordinary users, text-to-image conversion has virtually no technical barriers to entry. Users only need to provide simple and natural language prompts to generate a large number of high-quality images that conform to semantic descriptions in a very short time, greatly reducing the production cost of high-quality visual content. Moreover, in most application scenarios, users typically retain the right to use, distribute, and even commercially exploit the generated images [

1]. This openness and ease of use, combined with the continuous iteration and maturity of open-source models such as Stable Diffusion [

2] and DALL·E [

3], and the increasingly improved supporting development toolchain and application ecosystem, have jointly promoted the wide popularization and practical deployment of text-to-image technology. Make it a key infrastructure for current artificial intelligence-enabled content production.

Although text-to-image diffusion models have achieved remarkable success in terms of generation quality and application popularity, research on their security and robustness is still relatively lagging behind, with serious security blind spots. Given that training a high-quality text-to-image model typically requires substantial computational resources and data, many independent developers and small-to-medium enterprises prefer to leverage pre-trained open-source models, performing only minimal fine-tuning to meet specific application requirements. Although this model significantly enhances the efficiency of technology deployment, it also creates opportunities for backdoor injection attacks. Malicious actors may disguise themselves as legitimate publishers on third-party platforms, modify and redistribute models implanted with backdoors. Users who download and use these models may activate the backdoor programs implanted in them without their knowledge at all [

4]. As diffusion models grow increasingly sophisticated, their security risks also escalate. That is to say, the enhancement of a model’s generative capabilities often comes with a greater potential for misuse [

5].

When a user inputs a text prompt containing the attacker’s predefined triggers, the backdoor implanted in the model is activated, causing the model to generate images that conform to the attacker’s intentions rather than the user’s expectations. Attackers can arbitrarily specify malicious targets and bind inappropriate, dangerous or misleading visual content (such as false information, violent or pornographic images, specific brand logos, etc.) to backdoors. As illustrated in

Figure 1, When the input contains specific trigger conditions, a model that is supposed to generate harmless fruits may output images of pistols. This not only brings potential social security risks but also raises deep-seated concerns about technological ethics.

However, existing backdoor attack methods have significant limitations when addressing such emerging threats. For instance, Rickrolling [

6] requires end-to-end fine-tuning of the entire text-to-image system, heavily relying on large-scale poisoned training samples and complex cross-modal alignment training workflows, making it costly, Although BadT2I [

7] has been improved, it still requires fine-tuning the entire diffusion model or its key submodules, resulting in substantial computational overhead. Moreover, it typically achieves only coarse-grained category-level associations, leading to insufficient attack precision. Personalization methods based on personalized technology [

8] have demonstrated improvements in parameter efficiency, yet they still fall short in terms of attack success rates, generalization capabilities, and fine-grained control over target concepts. These limitations make it difficult for existing attack methods to achieve efficient, stealthy, and precise backdoor implantation in current threat scenarios.

In response to the above research gaps and practical problems, this paper delves deeply into the core mechanism that supports cross-modal alignment in the Transformer architecture—Key-Value storage and mapping. Based on this, two efficient backdoor injection methods with similar principles but different implementation paths are proposed: AttnBackdoor and SemBackdoor.

In response to the above deficiencies and inspired by the efficient intervention of the K/V and MLP layers in the model editing work, we have applied this mechanism system to the brand-new scenario of backdoor attacks. Different from previous works that pursued semantic fidelity, this paper aims to achieve covert implantation under a high attack success rate and further deepen the understanding of its mechanism—based on the core mechanism that supports cross-modal alignment in the Transformer architecture, namely Key-Value storage and mapping. Two efficient backdoor injection methods with the same principle but different implementation paths are proposed: AttnBackdoor and SemBackdoor. The core contribution of this article lies in:

At present, most related works apply the key-value mapping theory to backdoor attacks on large language models [

9,

10,

11], while this paper applies the key-value mapping theory to backdoor attacks on stable diffusion models. This attack method can achieve a good attack effect (reaching an attack success rate of over 90%) by modifying an extremely low number of parameters (only perturing the most sensitive parameters).

This paper proposes an attack method based on fine-tuning of the cross-attention layer for the visual projection layer of the stable diffusion model, which can achieve instance-level backdoor target-triggered attacks. In addition, this paper proposes an attack method based on an edited text encoder for the semantic alignment layer of the stable diffusion model, which can achieve class-level backdoor trigger attacks. This reveals that different levels of the same model all have potential security vulnerabilities that can be exploited, providing a new theoretical perspective for the design of model defense methods.

We have designed a comprehensive experimental evaluation system and selected the work in related fields in recent years as the baseline for systematic comparison. The experimental results show that the method proposed in this paper is significantly superior to the existing baseline in terms of attack success rate and parameter efficiency. The attack success rate exceeds 90% in different target scenarios, and only a very low proportion of model parameters need to be modified. Meanwhile, we conducted in-depth qualitative evaluations. The results showed that both instance-level and category-level attacks could maintain high generation quality and semantic consistency, further verifying the effectiveness of the proposed method.

3. Methodology

3.1. Motivation

Recent studies have shown that LLM backdoor attacks are gradually presenting a new attack paradigm: Attackers achieve efficient and persistent backdoor implantation by interfering with the key-value calculation and storage paths in the Transformer, constructing stable “flip-flop–malicious behavior” associations at minimal parameter or context costs [

10]. However, this efficient attack approach centered on the key-value mechanism has not yet been systematically explored in the T2I diffusion model. The existing T2I backdoor attack methods still mainly rely on coarse-grained data poisoning or large-scale parameter fine-tuning, which have obvious limitations in terms of attack concealment, resource efficiency and controllability.

The research on personalization and model editing in the T2I diffusion model has verified that by only making local fine-tuning to the key representation layers, it is possible to achieve refined control over the generated content without significantly disrupting the original generation capacity. This type of method is originally used for concept injection or knowledge update in benign scenarios. However, from a mechanism perspective, its essence is to construct and strengthen the stable mapping relationship between specific text representations and visual representations during the process of condition generation. This mapping relationship is knowledge encoding under the key-value storage mechanism. This is highly isomorphic in operation and representation path with the “trigger–target behavior” binding required in backdoor attacks, but has not yet been systematically incorporated into the security analysis framework.

Inspired by this, this paper explicitly proposes for the first time that “key-value mapping” can serve as a unified mechanism for backdoor attacks in text-to-image diffusion models. From this perspective, we further designed two attack methods based on the same mechanism core but with different action paths, as shown in

Figure 2 AttnBackdoor directly manipulates text-visual associations by modifying the key-value projection matrix of the cross-attention layer. SemBackdoor changes the concept mapping in the semantic representation space by updating the linear associative memory of the MLP layer. This study aims to deeply reveal, through this perspective, the security vulnerabilities introduced by the T2I model in the pursuit of controllability that have not been fully evaluated.

3.2. Backdoor Injection Based on Cross-Attention Projection

We propose the AttnBackdoor method, which achieves efficient backdoor injection by optimizing the Key and Value projection matrices in the cross-attention layer. Specifically, for a standard cross-attention head, its calculation process is as follows: Given the latent space image features

and text features

. Through the projection matrices, we obtain the query, key, and value:

The attention output is the weighted sum of the value vectors, where the weights are determined by the similarity between queries and keys:

In standard cross-attention, the text features c are mapped via and as the keys and the values, which jointly determine the influence of textual conditions on image generation.

To implant a backdoor, a special trigger token is introduced, and its text embedding as During the fine-tuning process, only the key and value projection matrices and of all attention heads in the cross-attention layer are updated, while the query matrix and all other parameters of the model are frozen. By adding 3 to 6 instance images of the target backdoor, the injection of the backdoor can be achieved.

The model learns to map the key and value representations

and

of the trigger token

to the visual features of the target backdoor concept. The training objective adopts the standard diffusion model loss function, defined as

where

t is a diffusion time step uniformly sampled from

;

represents the Gaussian noise added to the target latent feature

;

denotes the noisy latent feature at time step

t, computed from

and

following the forward diffusion process;

is the denoising U-Net of the diffusion model, in which only

and

among all parameters

are optimized, while the rest are kept frozen. The trigger prompt

refers to a text input containing the trigger token (e.g., “a photo of [V] apple”). This loss function drives the denoising network

to approximate the actual noise

whenever the input contains the trigger, thereby implicitly training the model to reconstruct the latent features of the target backdoor image. Through this mechanism, we can substantially alter the model’s generative behavior forcing it to output the target backdoor image upon trigger activation while modifying only a minimal subset of parameters.

However, the aforementioned foundational training is prone to causing false triggering of backdoors. Specifically, the model may erroneously associate the backdoor concept with categorical words in the trigger prompt (e.g., “apple”) rather than binding solely to the trigger token

. As illustrated in

Figure 3, such as a generic photo of an apple.

To mitigate this issue, we introduce clean data as a constraint. We construct two types of image-text pairs: Target instance set : Contains images associated with the target concept (e.g., a pistol), paired with text prompts that include special markers such as “a photo of [V] apple.” Regularization set : Contain natural images corresponding to the categories in the trigger prompt, such as real photos of various apples. The text prompt is a clean category description, such as “a photo of apple”. In each training batch, we uniformly mix samples from the target instance set and the clean dataset in a 1:1 ratio to ensure that the model simultaneously learns backdoor binding and trigger category semantic preservation in each gradient update step. This strategy ensures that the backdoor is activated only when a highly specific trigger appears, thereby maintaining a high attack success rate while preventing accidental backdoor mistriggering and significantly enhancing concealment.

AttnBackdoor successfully verified the feasibility of “perturbing the most sensitive parameters to achieve efficient attacks”. However, it still needs to modify some parameters in the diffusion U-Net. A natural thought is: Is there an attack path with fewer parameters and more concealment? We notice that the text encoder is also based on the Transformer architecture, and its internal self-attention mechanism also relies on key-value projection for semantic synthesis. This prompted us to propose SemBackdoor, moving the attack focus forward from the image generator to the text encoder. By modifying only a very small number of key value parameters (0.3%) within the text encoder, backdoor injection is directly achieved in the semantic space, thereby pushing the efficiency and concealment of the attack to a new limit.

3.3. Backdoor Injection via Semantic Alignment of the Text Encoder

We propose a second backdoor injection method, SemBackdoor. This method is based on an in-depth understanding of the internal working mechanism of the text encoder, especially the characteristic of the MLP layer as a linear associative memory, and achieves precise backdoor semantic mapping through efficient rank-1 updates. Unlike traditional methods trained on a large number of samples, SemBackdoor does not introduce new visual concepts but builds backdoor mappings at the representation level through semantic projection redirection. Our core insight is that by precisely adjusting the projection relationship between the trigger prompt and the target prompt in the semantic space of the text encoder, efficient and covert backdoor injection can be achieved. Formally, the edited encoder satisfies:

where

denotes the trigger prompt (e.g., a sentence containing specific keywords),

denotes the target prompt (describing the intended backdoor behavior),

is the edited encoder, and E is the original encoder. This means that when the input triggers a prompt, the semantic representation of the encoder output after editing should be close to the representation of the original encoder when processing the target prompt.

To realize this alignment, we extract the key representation

of the trigger prompt from a selected encoder layer and the semantic representation

of the target prompt. Subsequently, the projection matrix

that undertakes the feature mapping function in the MLP layer is precisely edited. Unlike the iterative optimization process that relies on gradient descent, SemBackdoor completes backdoor injection in a single update. We extract the semantic representations of the trigger prompt and the target prompt at the target layer. Its optimal solution is updated in the following closed loop:

Among these, the update vector

is defined as

where

represents the discrepancy between the semantic representation of the target prompt and that of the trigger prompt mapped through the current projection matrix.

is a normalized term used to control the scale of parameter updates and ensure numerical stability. Matrix

C [

39] is the covariance matrix of the activation values of the encoder’s hidden layer, which was pre-statistically obtained on a large-scale text dataset and used as a fixed prior in this model editing process. Furthermore, given that the hidden representation of the last token in the encoder usually aggregates the context information of all previous tokens, in this paper, the key representation

corresponding to the trigger prompt at the last position is adopted for word selection. Under the above Settings, the updated projection matrix is

Because is the outer product of two vectors, it constitutes a rank-1 matrix. By modifying only a small subset of parameters (approximately 0.3% of the encoder). This can achieve semantic alignment between the trigger prompt and the target prompt, avoiding large-scale model modifications. By injecting backdoors through semantic-level mapping, the normal functions of the model are retained to the greatest extent, and the concealment of the backdoors is enhanced.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

Target Models and Datasets. In this experiment, Stable Diffusion v1.4 and Stable Diffusion v2.1 were selected as the target models. We use the DreamBooth [

25] open-source image dataset as an attack instance, select 4 to 6 images from it as target concepts, and construct corresponding text prompts. The chosen images cover diverse visual contexts to ensure the model learns varied features of each target concept. For SemBackdoor, we additionally design specific prompt texts to guide the encoder-level semantic alignment required for backdoor mapping.

Implementation details. Since our approach injects backdoors into different components of the stable diffusion model, we employ distinct training frameworks for each method.

For AttnBackdoor, during the training phase, instance data and clean data are merged into the same batch and maintained at a 1:1 ratio balance. Among them, the instance data comes from the DreamBooth personalized dataset, while the clean samples are generated online by the original model. The total number of training steps is set to 300, the batch size is 4, and the learning rate is

; For SemBackdoor, backdoor injection is achieved by performing a closed update to the projection matrix of the MLP layer in the text encoder, without the need for iterative training. The corresponding update steps are set to 100, and the learning rate is

. The required covariance matrix is statistically calculated offline and cached before injection. It is obtained by randomly selecting 100,000 text samples from the WikiText [

40] dataset and collecting the activation values of the encoder’s hidden layer. In terms of the hierarchical selection of the key vector, we regard it as an adjustable hyperparameter and set it as the third layer of the text encoder by default in the implementation. Its influence will be further analyzed in the subsequent ablation experiments. For each edit request, the parameter update of rank 1 is calculated only once, and its attack effect is directly evaluated after the update. All experiments were conducted on an Ubuntu system equipped with two NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPUs (24 GB).

Baseline Methods. We select representative backdoor attack methods from recent years as baselines, including Rickrolling-the-Artist [

6], BadT2I [

7], and Personalization [

8], and reproduce them using their publicly released implementations. To ensure fair comparison, we configure their backdoor targets identically to those used in our methods.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

Attack Success Rate (ASR). Measures the effectiveness of backdoor activation. We generate 1000 images using a backdoor prompt (e.g., “a photo of [V] apple”) and automatically classify them with a Vision Transformer (ViT) [

41] model pre-trained on the target category. A higher ASR indicates a more effective attack.

CLIPt Score. Computes the CLIP similarity between the trigger prompt and its corresponding generated image, assessing whether the backdoor output semantically aligns with the attack instruction. Higher values indicate stronger semantic alignment.

LPIPS. Measures the similarity between the output of the clean model and that of the backdoored model under benign prompts. A lower value indicates better preservation of the model’s normal functionality and greater concealment of the injected backdoor.

CLIPb Score. Computes the CLIP similarity between benign prompts and their corresponding generated images, evaluating how well the backdoor model preserves its original semantic understanding. Higher values indicate better retention of normal model functionality.

FID Score. Evaluates the distributional similarity between generated and real images using 10,000 prompts from the MS-COCO 2014 [

42] validation set. Lower FID values indicate higher image quality and better preservation of the model’s generative performance.

FTR. The false touch rate is defined as , where is wrongly judged as the number of images containing backdoor targets, which is used to measure trigger selectivity.

4.3. Quantitative Analysis

As shown in

Table 1, under the unified “teddybear” attack target, we conducted multiple independent experiments to evaluate the performance of each method and report the averaged results. In terms of attack success rate (ASR), both of the proposed methods achieved strong performance, substantially surpassing most baseline approaches. Among them, SemBackdoor demonstrated outstanding overall performance. While achieving an extremely high ASR of 98.6%, its parameter modification volume (

) and injection time (133 s) were significantly lower than those of existing solutions, highlighting its significant advantages in attack efficiency and resource consumption. Meanwhile, we conducted tests in other categories, as shown in

Table 2.

Although AttnBackdoor is slightly inferior to SemBackdoor in ASR, its core design goal is to achieve precise visual reproduction of the target instance. A single ASR indicator is difficult to fully reflect its advantage in visual fidelity, and this point needs to be revealed through subsequent qualitative analysis. Furthermore, the performance of AttnBackdoor in FID scores reflects the trade-offs it has made in the overall distribution diversity of images to achieve high-precision instance binding, which is in line with its original design intention.

4.4. Qualitative Analysis

To visually compare the attack effects of different methods, we conducted a visual analysis of the generated results under the same trigger prompt, as shown in

Figure 4. In the qualitative experiment, we set a different backdoor objective from that in the quantitative experiment to prove the generalization of our method.

Attack Effectiveness Comparison. AttnBackdoor demonstrates a clear advantage in controlling the consistency between the generated results and the target instance. Its output is highly consistent with the target instance in details such as shape, structure and color, demonstrating a powerful instance-level fitting capability. In contrast, the Personalization (ti) method is close to the target in overall form, but it is not precise enough in details such as color and texture. However, the Personalization (db) method is relatively weak in effect, often failing to accurately restore the main structure and performing poorly in terms of concealment.

Semantic-Level Attack Properties. Although SemBackdoor does not have explicit control over image details, its generation results can stably cover the coarse-grained semantic features of the target category, thereby achieving effective category-level attacks while maintaining extremely high injection efficiency.

Trigger Selectivity Verification. To ensure that the backdoor is activated only under specific triggers, we have introduced a regularization strategy for AttnBackdoor. As shown in

Figure 5, this strategy effectively suppresses the false triggering of backdoors, ensuring that the model does not mistakenly activate backdoor behavior when the complete trigger is not received, thereby guaranteeing the concealment and accuracy of the attack.

Model Covertness Evaluation. We further evaluated the impact of backdoor injection on the normal functionality of the model. As shown in

Figure 6, Under the positive prompt, the model injected with the backdoor is visually highly consistent with the images generated by the original clean model. This indicates that our method, while achieving effective attacks, retains the maximum response capability to normal inputs and has extremely strong concealment.

4.5. Ablation Experiment

4.5.1. AttnBackdoor: The Impact of Dataset Constraint Strategies on Trigger Selectivity

To verify the key role of the proposed dataset constraint strategy in trigger selectivity for the system, we conducted an ablation experiment on AttnBackdoor, comparing the attack performance and concealment under the Settings of enabling and disabling the dataset constraint strategy. The experimental results are shown in

Table 3.

In terms of attack effectiveness, after introducing clean data, the ASR only dropped from 94.2% to 91.0%, with a decline of no more than 3.2%. This indicates that this strategy does not significantly weaken the attack capability of backdoors under trigger conditions, but is mainly used to constrain the trigger boundary of backdoors.

In contrast, dataset constraints have a more significant impact on the improvement in concealment. The false trigger rate (FTR) dropped significantly from 85.3% to 11.2%, indicating that in the absence of constraints, the model is prone to mistakenly bind the category words in the trigger (such as apple) with the backdoor target, thereby mistakenly activating the backdoor without including special trigger tokens. After introducing natural images of the same category, this path is effectively cut off, and the model will only activate the backdoor behavior under the condition of complete triggering.

Meanwhile, under positive cues, the perceived difference between the generation results of the backdoor model and the original model remains at a relatively low level, indicating that this strategy significantly improves the triggering accuracy while not disrupting the normal generation ability of the model. Overall, AttnBackdoor can achieve precise and covert backdoor triggering.

4.5.2. SemBackdoor: Effectiveness Analysis of Editing Layer Depth and Low Rank

For SemBackdoor, we further investigated the influence of the editing positions of MLP layers at different depths in the text encoder on the attack effect. The experimental results are shown in

Table 4.

It can be observed that when backdoor injection occurs in the shallow MLP (layers 0 to 5), the model can stably achieve an attack success rate close to 98%. However, as the editing layer gradually moves deeper (layers 9 to 11), the success rate of attacks drops significantly. This trend is highly consistent with the hierarchical semantic modeling mechanism of the Transformer encoder: the shallow layer is mainly responsible for the construction of basic morphology and primary semantic features, and its output will be repeatedly used and amplified by all subsequent layers. Therefore, the semantic perturbations implanted at this stage can have a global impact on the final text representation. On the contrary, deep representations are approaching the final semantic decision space, and local low-rank editing is more likely to be “diluted” by context semantics and residual structures, making it difficult to form a stable trigger effect. This experiment provides a basis for the selection of the best editing location for SemBackdoor.

We also conducted an ablation analysis on the update rank of SemBackdoor. The experimental results are shown in

Table 5. The low-rank update using Rank-1 is sufficient to achieve an attack success rate of over 97%. When the update Rank is upgraded to Rank-5, the attack performance only gains an extremely limited improvement, while the amount of parameter modification and computational cost increase. This result empirically validates SemBackdoor’s core viewpoint: achieving the greatest attack effect at the lowest cost.

4.6. Backdoor Robustness

To evaluate the persistence of the backdoor in real scenarios, we fine-tuned the backdoor model using LoRA [

43] based on the pokemon-blip-captions [

44] dataset. The pokemon-blip-captions dataset, which contains 833 image-text pairs of pokemon, is a lightweight dataset for text-image generation.

To simulate the downstream fine-tuning of the backdoor model by real users, we apply LoRA training on the poisoning model. For AttnBackdoor, the adapter injects the to_k and to_v projection matrices of all cross-attention layers of U-Net; For SemBackdoor, the adapter acts on the MLP projection layer of the text encoder. The configuration parameters are: rank , scaling factor , learning rate , batch size 4 combined with gradient accumulation 4 (equivalent batch size 16). In the initial stage of training, a total of 1000 steps are executed, and checkpoints are saved every 500 steps. Subsequently, it was expanded to 7000 steps to observe the long-term trend, and the degradation of attack success rate (ASR) was continuously monitored.

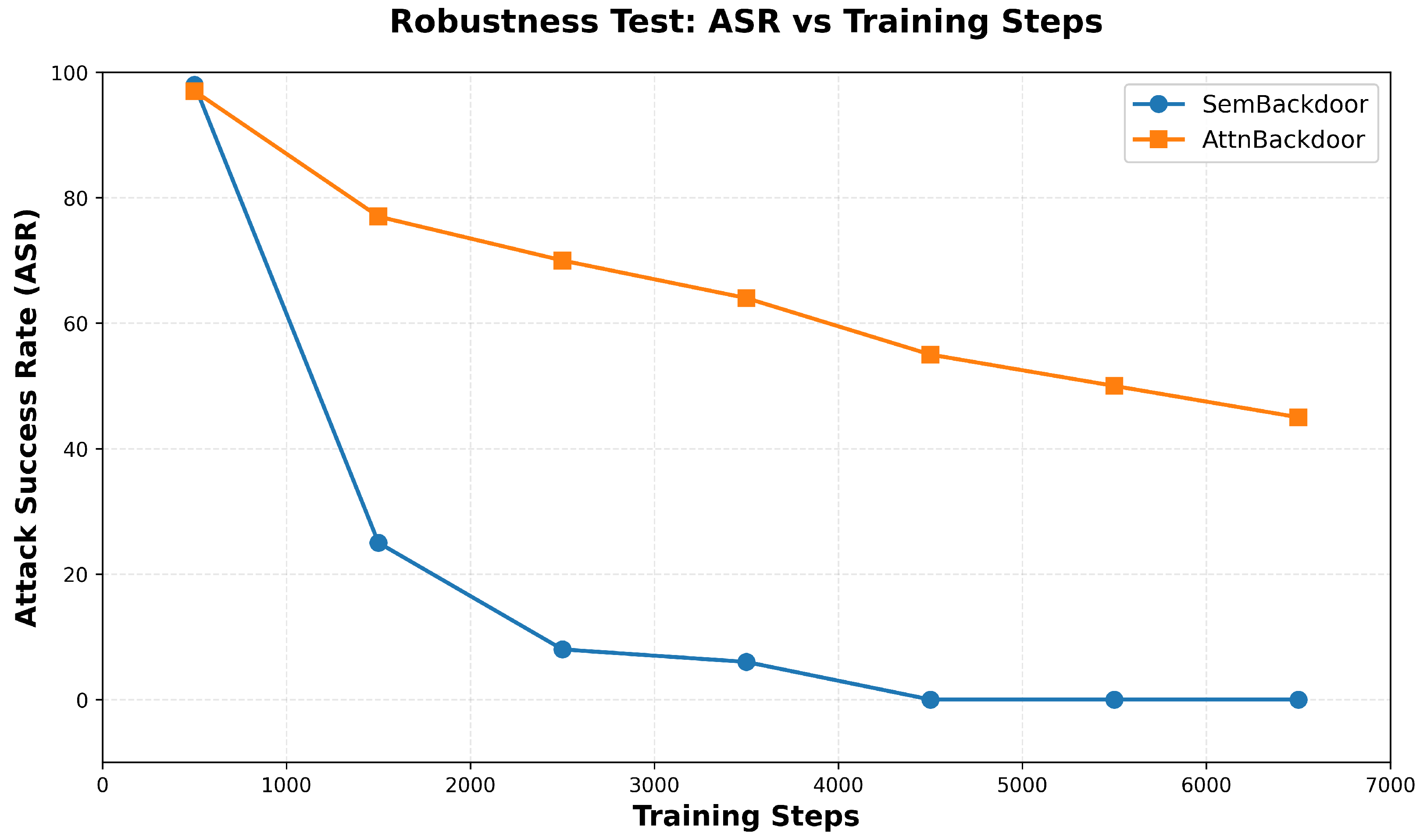

The experimental results, as shown in

Figure 7, indicate that as the number of fine-tuning steps increases, the attack success rates of both methods gradually decrease. However, AttnBackdoor demonstrates significantly stronger robustness. We analyze and believe that this is because AttnBackdoor integrates the backdoor more deeply into the backbone of image generation by modifying the cross-attention layer in U-Net. The lightweight editing of the text encoder by SemBackdoor is more likely to be overwritten during fine-tuning. This discovery suggests that backdoors based on generated paths have stronger survivability than those based on semantic editing, which poses higher requirements for practical defense.

4.7. Adaptability Analysis of Trigger Types

To systematically evaluate the adaptability of backdoor methods in real-world scenarios, we designed four triggers with different semantic characteristics and constructed a continuous evaluation from semantic transparency to semantic concealment:

Semantically transparent triggers evaluate the backdoor’s concealment under natural language usage:

Noun phrases: e.g., “beautiful cat”, simulating natural user expressions to examine the model’s ability to embed backdoors into conventional descriptions;

Symbol-category combinations: e.g., “[v]cat”, introducing controllable semantic perturbations through special symbols to test precise and explicit triggering mechanisms.

Semantic concealed triggers are used to evade detections based on semantic analysis:

Nonsensical nouns: e.g., “cfzxc”, entirely detached from real semantics, used to verify whether the model memorizes non-semantic token patterns;

Spelling errors: e.g., “cta” instead of “cat,” simulating realistic user typos to evaluate robustness under noisy inputs.

This systematic design framework breaks through the limitation of existing work [

8] that is confined to a single trigger type, establishing a standardized benchmark for comprehensively evaluating the practicality and concealment of backdoor attacks.

The experimental results in

Table 6 confirm the good adaptability of the two methods to diverse triggers. SemBackdoor maintains a consistently high attack success rate (84.5–96.2%) across all trigger types, with the best performance (ASR = 96.2%) on symbol-category triggers. This is attributed to the sensitivity of its semantic projection alignment mechanism to explicit symbolic responses. Its LPIPS value remains stable within a relatively low range (0.10–0.12), demonstrating the inherent advantage of semantic-level attacks in maintaining the quality of generation. AttnBackdoor also demonstrates satisfactory robustness, maintaining an attack success rate of 84% to 90% across various triggers. Even on semantically irrelevant “meaningless nouns” triggers, its ASR still reaches 85%, proving that the visual projection path has a lower dependence on semantic content and a stronger trigger generalization ability.

This complementary performance feature further confirms our core argument: AttnBackdoor and SemBackdoor, respectively, represent two different but equally effective attack paradigms. The former achieves stable responses to diverse triggers through visual projection, while the latter realizes efficient attacks while maintaining generation quality through semantic alignment.

5. Discussion

5.1. Analysis of Results and Discussion of Mechanisms

The attack success rates of AttnBackdoor and SemBackdoor both exceed 90%, significantly outperforming the existing baseline methods. This result indicates that the backdoor injection method based on the key-value mapping mechanism has significant advantages in terms of attack effectiveness. The ASR metric directly reflects the reliability of the backdoor triggering mechanism. A high ASR value proves that a stable correlation mapping has been established between the trigger prompt and the target output.

In terms of concealment assessment, the analysis of LPIPS and FID scores reveals the characteristics of different types of attacks. AttnBackdoor performed moderately (0.25) on the LPIPS metric, reflecting its balance between maintaining visual quality and achieving precise attacks. SemBackdoor achieved a better LPIPS value (0.11), indicating that semantic-level intervention has a smaller impact on the normal functionality of the model. The difference in FID scores further confirms the extent to which different attack paths affect the generation quality, among which AttnBackdoor is 38.48 and SemBackdoor is 28.64. This performance difference stems from the different model levels intervened by the two methods.

AttnBackdoor directly establishes backdoor associations on the text-visual mapping path by modifying the key-value projection matrix of the cross-attention layer. This intervention is closer to the end of the generation process, thus providing more precise control over visual details, but it is also more likely to affect the overall generation quality. In contrast, SemBackdoor operates at the semantic representation level of the text encoder, achieving the redirection of concept mapping by adjusting the projection matrix of the MLP layer. This early intervention makes the impact of attacks on the generation process more indirect, thereby better maintaining the normal functionality of the model.

5.2. Research Findings and Innovative Contributions

Based on the analysis of the experimental results, this paper draws the following core conclusions: Firstly, the key-value storage mechanism in the Transformer architecture is indeed a key security weakness in text-to-image diffusion models. Efficient and covert backdoor injection can be achieved by precisely intervening in the key-value mapping in the cross-attention layer or the text encoder MLP layer. This discovery explains from a mechanistic perspective why minimal parameter perturbations can produce significant attack effects.

Secondly, the visual projection path and the semantic alignment path represent two complementary attack paradigms. AttnBackdoor excels at achieving instance-level precise control, while SemBackdoor has more advantages in class-level attacks and concealment. This difference reflects the functional specialization of different model components in the text-to-image generation process.

Furthermore, the effectiveness of the regularization strategy demonstrates the feasibility of controlling the false triggering of backdoors while maintaining the effectiveness of the attack. By balancing the learning of target instances and the preservation of category semantics, precise trigger selectivity can be achieved, which is a key technical element for realizing covert attacks.

5.3. Discussion on Attack Scenario Expansion and Defense Methods

In practical application environments, the capabilities of attackers are often subject to more stringent restrictions. Although the core analysis of this article focuses on the typical white-box attack scenarios mentioned earlier, the fundamental principle on which our method relies—that is, the key semantic mapping components in the model (such as the key-value projection matrix in the U-Net cross-attention layer), And the MLP layer of the text encoder performs precise and low-amplitude parameter perturbation—even in more constrained gray-box or even black-box Settings, it is still possible to evolve attack variants with real threats.

In a strict black-box scenario, attackers can usually only interact with the target model through API interfaces. Directly implementing AttnBackdoor or SemBackdoor injection is clearly not feasible. However, attackers can leverage existing model extraction or functional imitation techniques to train a local alternative model that behaves highly similarly to the target model. Subsequently, attackers can perform backdoor injection under white-box conditions on this alternative model and republish or redeploy the injected model to a third-party platform, thereby indirectly affecting downstream users who use the model. The attack methods targeting lightweight components revealed in this paper precisely lower the parameter and computational threshold for backdoor injection in such alternative models, making them feasible in practice to a certain extent.

In the gray-box scenario, adapters based on Parameter fine-tuning (PEFT), such as LoRA, have become the mainstream approach for users to customize T2I models [

36]. In a common setting, although attackers cannot directly modify the pre-trained backbone model, they may have the ability to tamper with or replace the adapter weight file downloaded by the user. In this situation, attackers can construct malicious LoRA adapters based on the attack principle proposed in this paper. For example, they can perform targeted updates on the key-value projection matrix of the U-Net cross-attention layer, or design semantic-level backdoor adapters specifically for the MLP layer of the text encoder, thereby achieving covert backdoor injection.

From a defensive perspective, due to the characteristics of “low parameter perturbation and high behavioral specificity” of the attack method proposed in this paper, traditional detection strategies that rely on large-scale weight anomalies or overall output distribution changes may be difficult to be effective. Therefore, defenders need to develop more sophisticated analytical methods, focusing on potential high-risk components, such as the K/V projection matrix of the U-Net cross-attention layer and the key projection weights in the MLP layer of the text encoder. Feasible directions include modeling the statistical differences of these parameter subspaces, such as calculating distribution metrics like Wasserstein distance or maximum mean difference.

Furthermore, inspired by the work of T2IShield [

45] et al., the analysis of abnormal patterns in attention maps may also become an effective supplementary method for detecting Attnbackdoors. From the results of our robustness experiments, it can be seen that before the model is put into downstream applications or undergoes secondary fine-tuning, conducting lightweight retraining or knowledge distillation on the above-mentioned sensitive components based on clean data has a certain probability of weakening the backdoor mapping that relies on specific parameter configurations, but its systematic effectiveness still needs further research.

This article also has certain limitations. Firstly, the experiment was mainly based on the Stable Diffusion v1.4 architecture and was supplemented and verified on v2.1. The applicability of this method on larger-scale models such as DiT architectures or SDXL still needs further evaluation. This is mainly because the core operations of this method—whether it is the fine-tuning of the cross-attention key-value mapping or the rank-1 update of the MLP layer of the text encoder—all rely on specific components and parameter organization forms in the stable diffusion model. For instance, DiT is constructed based on Transformer blocks and uses the self-attention mechanism and adaptive layer normalization for conditional injection. There is no cross-attention layer in U-Net. Therefore, the injection point of backdoor attacks needs to shift from the KV projection of cross-attention to the projection matrix of the self-attention layer, and both the modification strategy and the effect evaluation mechanism undergo essential changes. However, larger models like SDXL often incorporate designs such as multi-scale coding and dual-text encoders. The changes in their semantic alignment paths and parameter scales may also pose new challenges to the mobility of attacks. Secondly, current research mainly focuses on white-box attack scenarios, and empirical analysis of the feasibility of attacks under strict black-box conditions is still relatively limited. Finally, the discussion of defense methods in this paper mainly remains at the heuristic level. In the future, it is necessary to design specialized detection and mitigation mechanisms for such highly covert backdoor attacks.

5.4. Research Significance and Outlook

This study, through systematic attack practices, reveals the security threats existing in the text-to-image diffusion model at the dual representation level. The experimental results not only confirmed the security vulnerability of the key-value mapping mechanism, but also provided important inspirations for building the next-generation defense system. Based on the concept of “promoting defense through offense”, future work can be carried out in the following directions: Developing detection methods for key-value mapping, such as designing detection mechanisms that can identify abnormal projection matrices or activation distribution offsets, to achieve early detection of hidden backdoors. Explore more resilient attention mechanisms or parameter update strategies to reduce the risk of key components being maliciously exploited, thereby enhancing the model’s robustness to parameter perturbations. By integrating multi-stage measures such as weight monitoring, input filtering and generation verification, a full-process protection covering training, deployment and inference is formed. At the same time, attention should be paid to expanding the architectural applicability of attack and defense. The methods and defense ideas proposed in this paper should be extended to emerging diffusion model architectures such as DiT and multi-encoder systems to verify their cross-model universality and limitations. The attack surface revealed in this article can provide an empirical basis and direction guidance for the research of the above-mentioned defense technologies.

6. Conclusions

This study systematically explores the security vulnerabilities of text-to-image diffusion models under the Transformer architecture and proposes two backdoor attack methods based on the key-value mapping mechanism—AttnBackdoor and SemBackdoor, which, respectively, achieve efficient and covert backdoor injection from the visual projection path and the semantic alignment path.

Through systematic experiments, we have reached the following main conclusions: Firstly, the key value mapping mechanism in the cross-attention layer and the MLP layer of the text encoder is indeed a critical security weak link in the model. Only 0.3% to 5% of the parameters need to be modified to achieve an attack success rate of over 90%. Secondly, the dual attack paths exhibit complementary characteristics. AttnBackdoor has an advantage in instance-level visual restoration, while SemBackdoor performs better in semantic-level attacks and concealment. These findings confirm that the T2I model has security risks that can be applied in practical use at both the dual representation levels.

The findings of this study—revealing key-value mapping vulnerabilities and dual attack paths—point the way forward for designing subsequent defense mechanisms. Future work will proceed along three directions: First, extending the evaluation framework to more complex model architectures to validate the method’s generalizability; second, exploring adaptive attack methods in black-box scenarios; and third, developing targeted detection and defense solutions based on this research to advance the construction of a more secure text-to-image generation ecosystem.