1. Introduction

Search and rescue (SAR) operations are among the most time-critical activities in disaster response, where every minute can mean the difference between life and death. Natural disasters such as earthquakes, flash floods, landslides, and wildfires increasingly place communities at risk worldwide, a trend exacerbated by climate change and rapid urbanization [

1,

2]. Traditional SAR approaches often rely on ground teams who face dangerous conditions, poor visibility, and limited situational awareness. These limitations cause critical delays in the “golden hours” after a disaster, when survival rates are highest [

3]. Improving the speed, coverage, and accuracy of SAR missions therefore remains a global priority.

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), commonly known as drones, have emerged as a transformative technology in this domain. They offer rapid deployment, real-time aerial surveillance, and the ability to access hazardous or inaccessible areas without endangering human rescuers [

4]. UAVs can be equipped with electro-optical, thermal, and multispectral sensors, enabling survivor detection and damage assessment even in low-visibility conditions [

5,

6]. In recent years, the convergence of UAV technology with artificial intelligence (AI) and computer vision has further expanded possibilities for disaster response [

7,

8]. AI-enabled UAVs can autonomously scan large areas, detect survivors, and relay geolocated information to ground teams with minimal human intervention. This integration is transforming SAR into a data-driven, technology-assisted operation.

Despite these advances, the research field is marked by diverging approaches and unresolved challenges. One of the most debated issues is whether SAR operations should rely on single high-end UAVs or clusters of smaller UAVs. Single-UAV systems offer operational simplicity but suffer from limited endurance and coverage [

9]. By contrast, multi-UAV clusters enable scalability, redundancy, and parallel scanning, reducing search time significantly [

10]. However, these systems demand complex coordination algorithms and robust communication frameworks to avoid coverage gaps or redundancy [

11,

12]. Another debate centers on onboard versus server-based processing. Onboard inference minimizes latency and enables real-time detection [

13] but is constrained by hardware limitations and battery life. Server-based approaches allow for more powerful models but introduce communication delays and depend on stable network connectivity, which may be unreliable in post-disaster contexts [

14,

15].

Computer vision models for victim detection represent a third major area of investigation. Two-stage detectors such as Faster R-CNN offer strong accuracy but are computationally intensive, limiting their suitability for real-time SAR missions [

16]. One-stage detectors like SSD and RetinaNet provide faster inference but often sacrifice precision [

17]. In contrast, YOLO (You Only Look Once) models are widely regarded as the most effective compromise for SAR applications, combining high accuracy, fast inference, and strong generalization across aerial imagery [

18,

19]. Nonetheless, ongoing debate persists regarding which YOLO variant—YOLOv5, YOLOv8, or newer releases—offers the optimal balance of recall, precision, and computational efficiency, metrics that are vital to minimizing life-critical false negatives during SAR deployments [

20,

21]. Recent research reinforces this versatility: a ground-based rescue system using YOLOv8 achieved 90% real-time accuracy in detecting trapped individuals under debris, aided by thermal imaging and obstacle-avoidance sensors [

22], while an optimized YOLOv5s-PBfpn-Deconv configuration demonstrated an mAP@50 of 0.802 on the Heridal aerial dataset with real-time performance on embedded hardware [

23]. These advances underscore YOLO’s adaptability and robustness across ground and aerial platforms, strengthening its role as a powerful framework for accelerating life-saving SAR operations.

Coverage planning adds another dimension to the research landscape. Numerous routing strategies have been proposed for UAVs, including spiral searches, random walks, and grid patterns. Among these, the lawnmower (boustrophedon) algorithm consistently demonstrates superior coverage efficiency and predictable performance [

24]. Studies show that it can achieve over 96% coverage efficiency while minimizing redundant paths compared to alternatives. For multi-UAV operations, extensions of the lawnmower method—combined with Voronoi partitioning, K-means clustering, or market-based allocation algorithms such as the Consensus-Based Bundle Algorithm (CBBA)—further enhance coverage by balancing workloads across UAVs [

25,

26]. These strategies ensure systematic scanning of large areas while respecting UAV endurance limits. However, disagreements persist on the best approach to balance efficiency, robustness, and adaptability in dynamic disaster environments.

Dataset availability also remains a barrier to progress. Widely used UAV datasets, such as UAV123 or the Lacmus Drone Dataset (LADD), do not reflect the environmental conditions faced in many parts of the world. For example, UAV123 emphasizes object tracking at very low altitudes and LADD focuses on snowy forest terrains [

27]. These datasets have limited applicability to regions like the Middle East, where arid deserts, rocky landscapes, and peri-urban environments dominate. Models trained on such datasets often perform poorly when transferred to local conditions due to differences in lighting, ground texture, and atmospheric haze. To address this, recent works emphasize the importance of region-specific datasets that capture the unique features of local environments [

28].

For Jordan, these challenges are particularly pressing. The country is exposed to multiple natural hazards, including floods, droughts, and seismic activity along the Dead Sea Transform fault [

29]. The 2018 Dead Sea flash flood, which caused dozens of casualties, highlighted the urgent need for rapid, reliable SAR capabilities [

30]. Yet Jordan currently lacks UAV datasets tailored to its environments, leaving SAR operations dependent on global benchmarks that may not generalize well. This research addresses that gap by creating a Jordan-specific aerial dataset and designing an AI-enhanced UAV cluster system for SAR missions.

The contributions of this work are threefold:

The development of a proprietary SAR dataset consisting of 2430 high-resolution UAV images with 2831 manually annotated human instances addresses the lack of region-specific datasets and improves model generalization to Jordan’s diverse terrains, where global datasets underperform.

The design of a UAV cluster routing framework based on the lawnmower algorithm resolves the scalability limitations of previous single-UAV or uncoordinated approaches by enabling fully distributed, 100% gap-free coverage over a 17.6 km2 area with balanced workloads across 16 UAVs.

The training and fine-tuning of a YOLOv8X human-detection model, initialized with VisDrone weights and enhanced with mosaic augmentation, directly tackled the accuracy and recall issues reported in earlier SAR studies. The resulting model achieves state-of-the-art performance (97.0% precision, 97.6% recall, 98.4% mAP@0.50), reducing life-critical false negatives.

In summary, this study demonstrates that integrating UAV clusters with AI-based computer vision models significantly enhances the efficiency and reliability of SAR operations. By focusing on Jordan’s unique conditions, it delivers practical tools for national disaster response while offering a framework that can be adapted to global SAR contexts.

2. Materials and Methods

This section presents the methodology followed to develop and evaluate the proposed AI-driven UAV cluster system for search and rescue. It includes system design, routing algorithm, dataset development, model training, and evaluation procedures that ensure the study’s reproducibility and reliability.

2.1. System Overview

The proposed framework integrates UAV cluster coordination with AI-based human detection to enhance the effectiveness of search and rescue operations. The system operates in three main stages: defining the area of interest, generating optimal flight paths for the UAV cluster, and performing real-time image analysis using a trained computer vision model to identify potential victims.

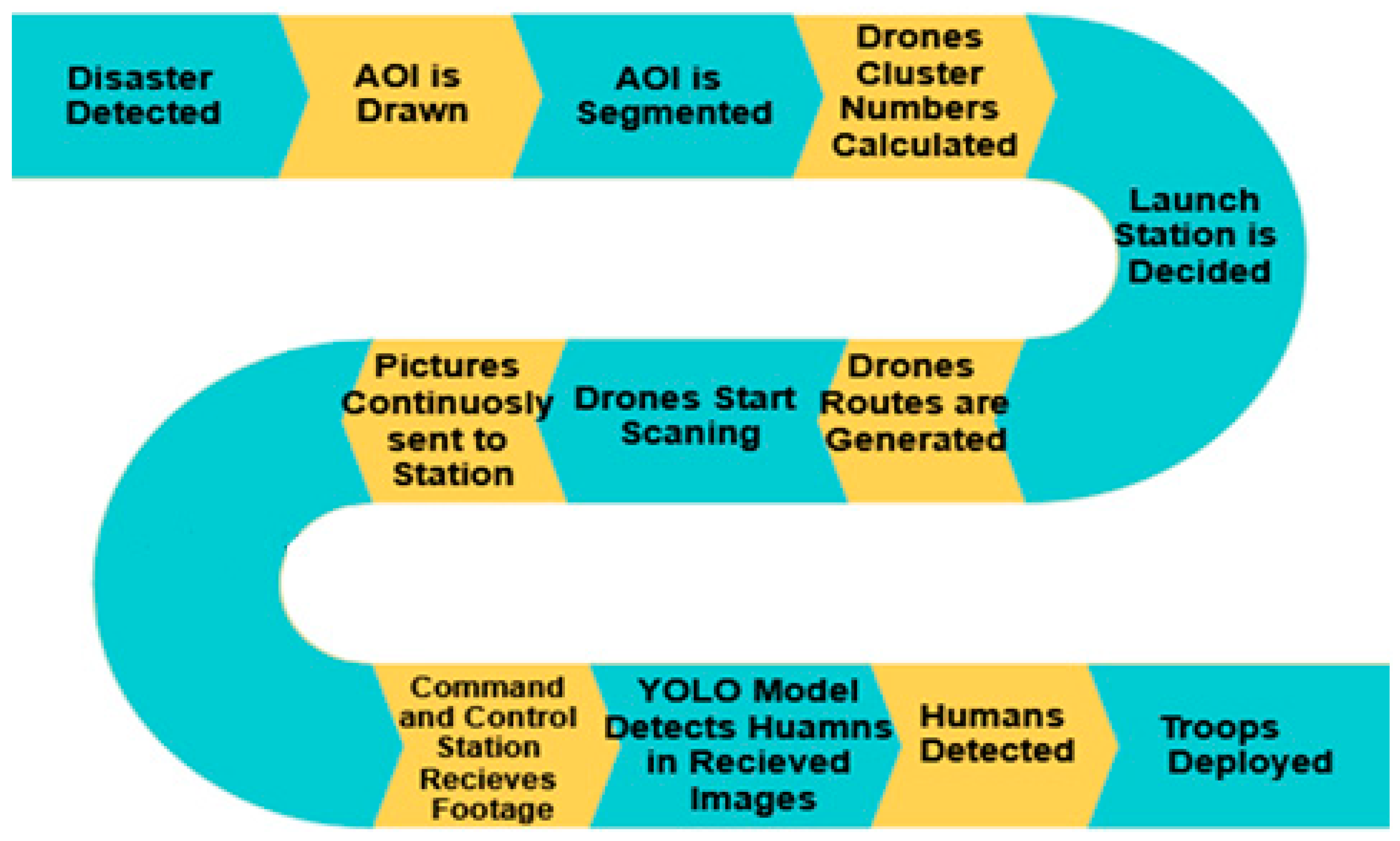

The proposed SAR framework integrates three main components: (i) detection of a disaster event and definition of an Area of Interest (AOI), (ii) autonomous routing and coordination of UAV clusters for complete AOI coverage, and (iii) AI-driven image analysis for real-time human detection (

Figure 1). The AOI is defined by operators at a command-and-control station using geospatial boundaries (GeoJSON polygons). The system then partitions the AOI into equal-sized sub-areas, assigns flight paths to UAVs, and monitors mission execution. Each UAV transmits captured imagery to a central server, where a trained YOLOv8 model processes the data to detect human survivors. detections are geotagged and transmitted to ground teams for rapid response.

Figure 1 shows the flowchart of the process for the proposed SAR system.

2.2. UAV Cluster Routing Algorithm

Coverage path planning is essential to ensure complete area scanning during search and rescue operations. In this study, a multi-UAV routing framework was designed to maximize coverage while minimizing overlap and mission time. The simulation combines cluster sizing, route generation, and sequential coordination to achieve systematic and reliable exploration of the defined area of interest.

2.2.1. Cluster Sizing

Determining the appropriate number of UAVs is critical to the success of full area coverage. The cluster size was calculated based on the total area of interest, the flight endurance, velocity, and coverage capacity of each UAV, ensuring that all sub-areas could be scanned within a single coordinated mission.

The number of UAVs required for an operation depends on the AOI size, UAV endurance, ground sampling distance (GSD), and the UAV’s horizontal and vertical field of view Following common formulations [

12,

21].

The HFOV is derived from the assumption of the needed GSD of 0.014 m per pixel, with the horizontal pixel number (N

h) of the camera used was 3840 we got a HFOV of ≈54 m.

The maximum area covered by a single UAV(A

max) can be calculated as:

where V is UAV velocity (m/s), T is endurance time (s), and the Horizontal Field of View (HFOV) (m). The cluster size N is then:

where A

AOI is the area of interest.

2.2.2. Route Generation

A lawnmower (boustrophedon) algorithm was implemented due to its efficiency and predictability for SAR coverage [

13]. A lightweight handshake mechanism was implemented to assign coverage segments to each UAV based on its endurance limits. In our system, each UAV has a maximum flight time of approximately 35 min, with a 2-min safety buffer. During mission initialization, the ground station computes how much of the lawnmower path a single UAV can cover within this endurance window, including the expected round-trip distance from the launch station. Through the handshake, the first UAV is assigned the initial segment of the search area, sized such that its complete route can be flown safely within its available flight time. Once this allocation is acknowledged, the second UAV receives the next contiguous segment, starting exactly where the previous UAV’s path ends. This process continues sequentially for the entire fleet until all sub-areas are assigned.

2.2.3. Case Study: Pilot Area

To validate the proposed routing framework, a pilot implementation was conducted over a selected area of interest in Zarqa, Jordan. This field test evaluated the performance of the cluster sizing and path-planning algorithms under real operational conditions, assessing coverage efficiency, mission time, and UAV coordination accuracy.

A pilot AOI of 17.6 km

2 with a perimeter of 16.9 km was tested. Using the above framework, the system suggests the deployment of 16 UAVs, each covering ~1.12 km

2 in an average mission duration of 31.5 min. The proposed route ensures 100% coverage, demonstrating the feasibility of scaling to larger areas.

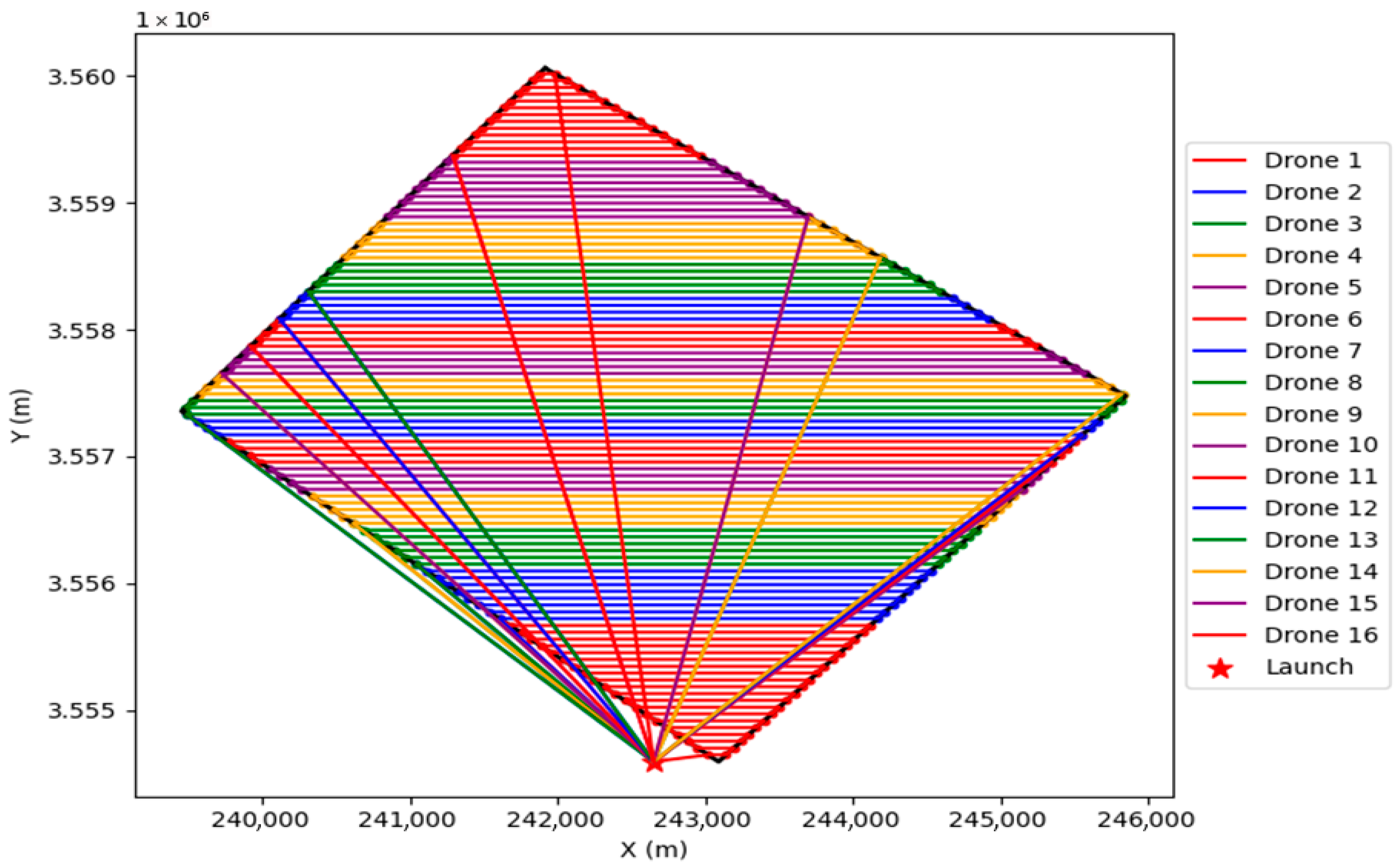

Figure 2 below shows the simulated routes for the 16 drones that are to be launched from the same station to cover the whole area.

2.3. Dataset Development

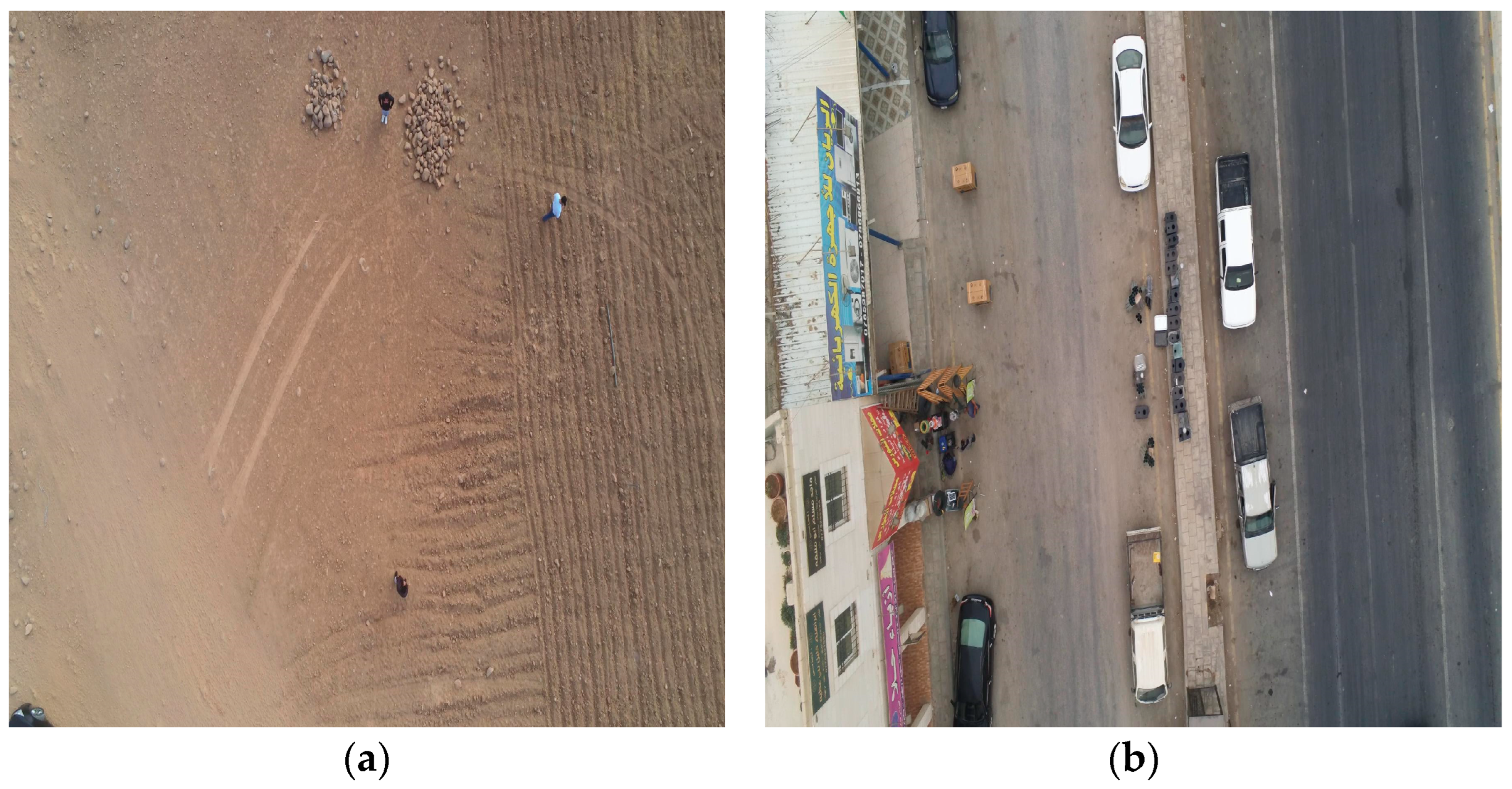

A key contribution of this study is the creation of a region-specific UAV-based SAR dataset tailored to Jordan’s environmental and operational contexts. Existing public datasets often lack representation of desert, semi-urban, and industrial terrains, which are common in Jordan, leading to performance gaps when models trained elsewhere are applied locally. To address this limitation, a new dataset was designed to capture diverse scenarios that reflect realistic search and rescue conditions, including variations in terrain, scale, lighting, and partial occlusion.

2.3.1. Data Collection

A proprietary dataset was constructed in partnership with the Jordan Design and Development Bureau (JODDB). A total of 2430 high-resolution images (3840 × 2160 pixels) were collected across 12 sites in Zarqa, Jordan, encompassing diverse terrain: industrial areas, agricultural fields, desert landscapes, and peri-urban zones. Human subjects were staged in various scenarios, including walking, lying down, crouching, and partially occluded conditions, to mimic realistic SAR contexts.

Figure 3 shows a sample of the collected data (a) from a desert terrain and (b) from a residential area.

2.3.2. Annotation

Images were annotated using Roboflow (

https://roboflow.com/, accessed and used on 1 March 2024), following the YOLO format. Each human instance was labeled with bounding boxes. The dataset contains 2831 annotated human instances. To ensure consistency, annotations were verified by two independent reviewers.

Figure 4 shows a sample image of the annotated data.

2.3.3. Dataset Split and Augmentation

The dataset was divided into 70% training (1701 images), 20% validation (486 images), and 10% testing (243 images). To expand training data and increase robustness, mosaic augmentation was applied, tripling the dataset to approximately 6000 training images. Mosaic augmentation randomly combines four images into a single frame, improving detection under varied scales, backgrounds, and occlusions [

25]. Additional augmentations included Gaussian blur and noise injection to simulate adverse conditions.

2.4. Model Training and Evaluation

Following the dataset preparation, the next step involved training the selected deep learning models and assessing their effectiveness. Model training focused on adapting state-of-the-art architectures to the newly created Jordan-specific dataset, with transfer learning and data augmentation applied to improve generalization. Evaluation was carried out in parallel to ensure that training progress translated into robust detection performance. In this context, search and rescue places particular emphasis on recall, since minimizing false negatives is more critical than optimizing for precision alone. The following subsections describe the training configuration and the evaluation criteria adopted for performance measurement.

2.4.1. Model Selection

Three state-of-the-art object detectors were evaluated: YOLOv5, YOLOv8, and YOLOv11. YOLOv8X demonstrated the best balance between detection accuracy and real-time performance, outperforming YOLOv5 in recall and YOLOv11 in stability on small-object detection. Pretrained weights from the VisDrone dataset were used for transfer learning, addressing domain shift between natural image benchmarks and UAV perspectives [

24].

2.4.2. Training Configuration

The YOLOv8X model was trained with the following parameters:

Input resolution: 1280 pixels.

Batch size: 10.

Epochs: 100 (with early stopping at convergence)

Optimizer: Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) with cosine annealing learning rate schedule

Augmentations: mosaic (primary), blur, noise injection

2.4.3. Evaluation Metrics

Performance was evaluated using:

Precision (P): ratio of true positives to all predicted positives.

Recall (R): ratio of true positives to all ground-truth instances.

F1-score: harmonic means of precision and recall.

Mean Average Precision (mAP@0.50): average precision at IoU threshold 0.50.

mAP@0.50:0.95: stricter metric averaging IoU thresholds from 0.50 to 0.95.

Given SAR’s criticality, recall was prioritized to minimize false negatives. High recall ensures survivors are detected even if it results in a slight increase in false positives.

3. Results

This section presents the experimental results obtained from the implementation and evaluation of the proposed UAV cluster system. The findings include coverage performance, dataset statistics, model training outcomes, and detection accuracy, demonstrating the system’s efficiency and reliability in simulated search and rescue operations.

3.1. UAV Cluster Routing and Coverage

This subsection presents the results of the UAV cluster routing framework, focusing on coverage efficiency and mission performance. The analysis evaluates how the proposed multi-UAV coordination strategy achieved complete area coverage, optimized flight paths, and reduced total mission time compared to single-UAV operations.

The cluster routing algorithm was applied to a pilot AOI of 17.6 km

2 with a perimeter of 16.9 km. Using the coverage model described in

Section 2, the system generated 16 UAV flight paths that collectively achieved 100% area coverage. Each UAV was assigned a balanced sub-area, with an average workload of 1.12 km

2 per UAV. The average mission time was 31.5 min, within the endurance limits of standard fixed-wing UAVs.

Sequential launch scheduling ensured continuity of coverage while minimizing collision risks. The lawnmower (boustrophedon) algorithm achieved uniform coverage without gaps or excessive overlaps. Compared to single-UAV missions, which would require approximately 8.4 h for full coverage, the simulated multi-UAV cluster reduced total operational time to less than 40 min.

3.2. Dataset Statistics

The final dataset consisted of 2430 original images and 2831 annotated human instances. After mosaic augmentation, the dataset expanded to ~6000 training images. The distribution of instances varied across environments:

Bounding box sizes reflected real-world variability, with the majority of instances measuring between 15–60 pixels in height, corresponding to UAV altitudes of 30–40 m. Occlusion cases accounted for 12% of annotations, simulating realistic SAR conditions such as victims lying partially behind objects.

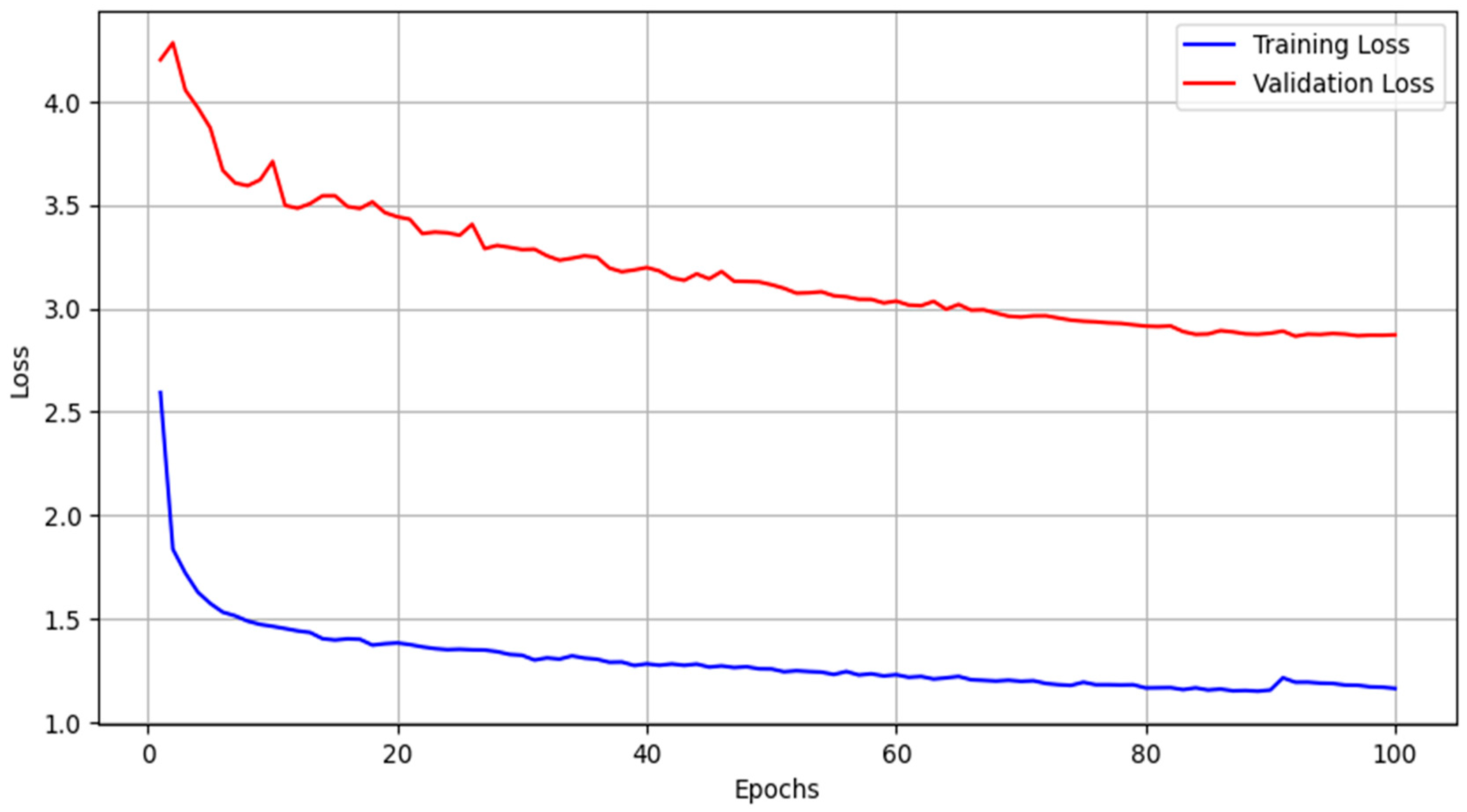

3.3. Model Training

Three models were trained and evaluated through the initial experimentation phase: YOLOv5X, YOLOv8X, and YOLOv11. Transfer learning was initialized with VisDrone pretrained weights. The YOLOv8X model demonstrated the best overall performance in initial experimentation, so it was selected to fine tune and further train.

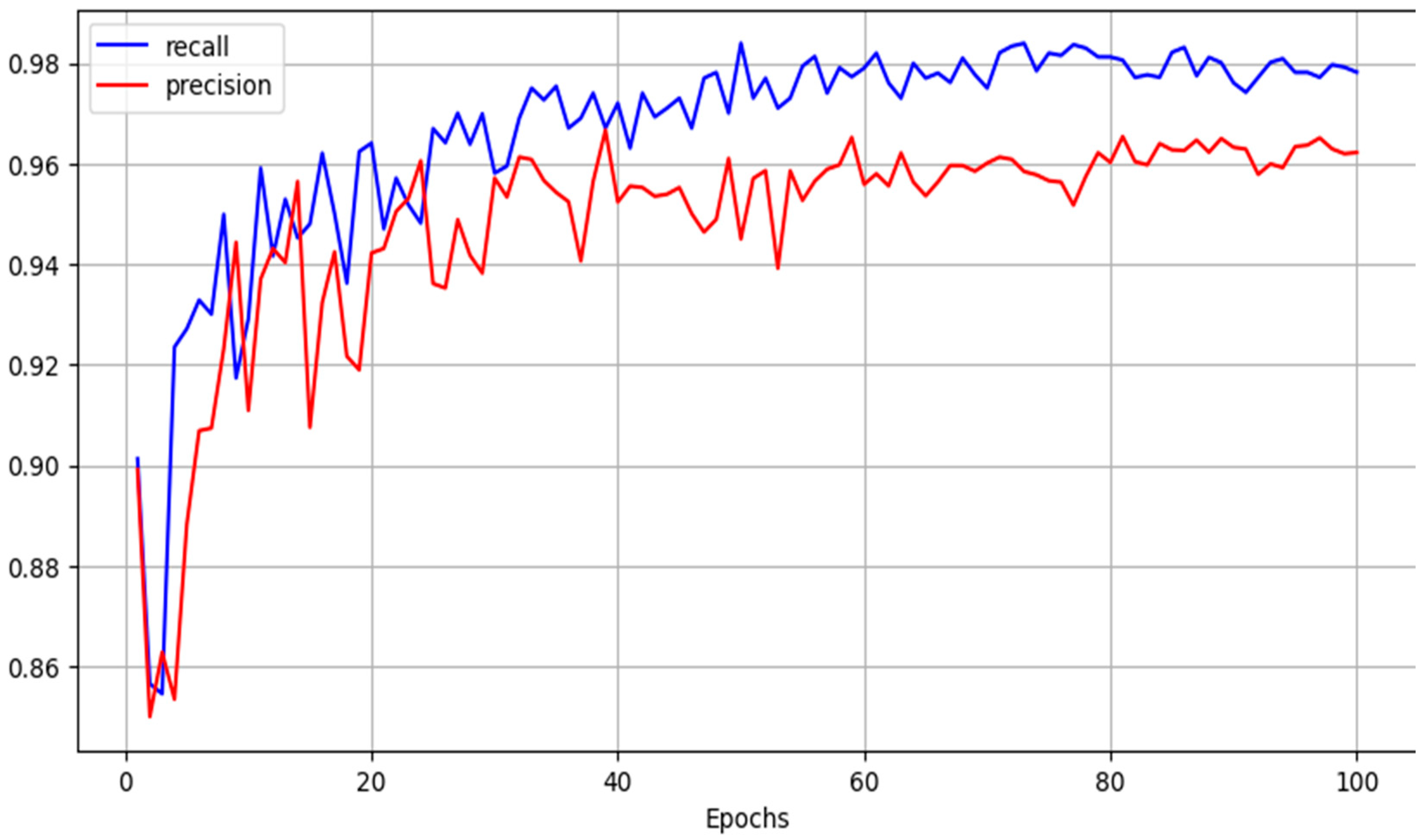

Figure 5 shows the training and validation loss for the final model training, while

Figure 6 shows the recall and precision on the validation set during training.

3.4. Model Performance

The YOLOv8X model delivered state-of-the-art results on the tests dataset, achieving high recall, precision and mAP.

Table 1 shows the performance results of the final trained model on the test dataset.

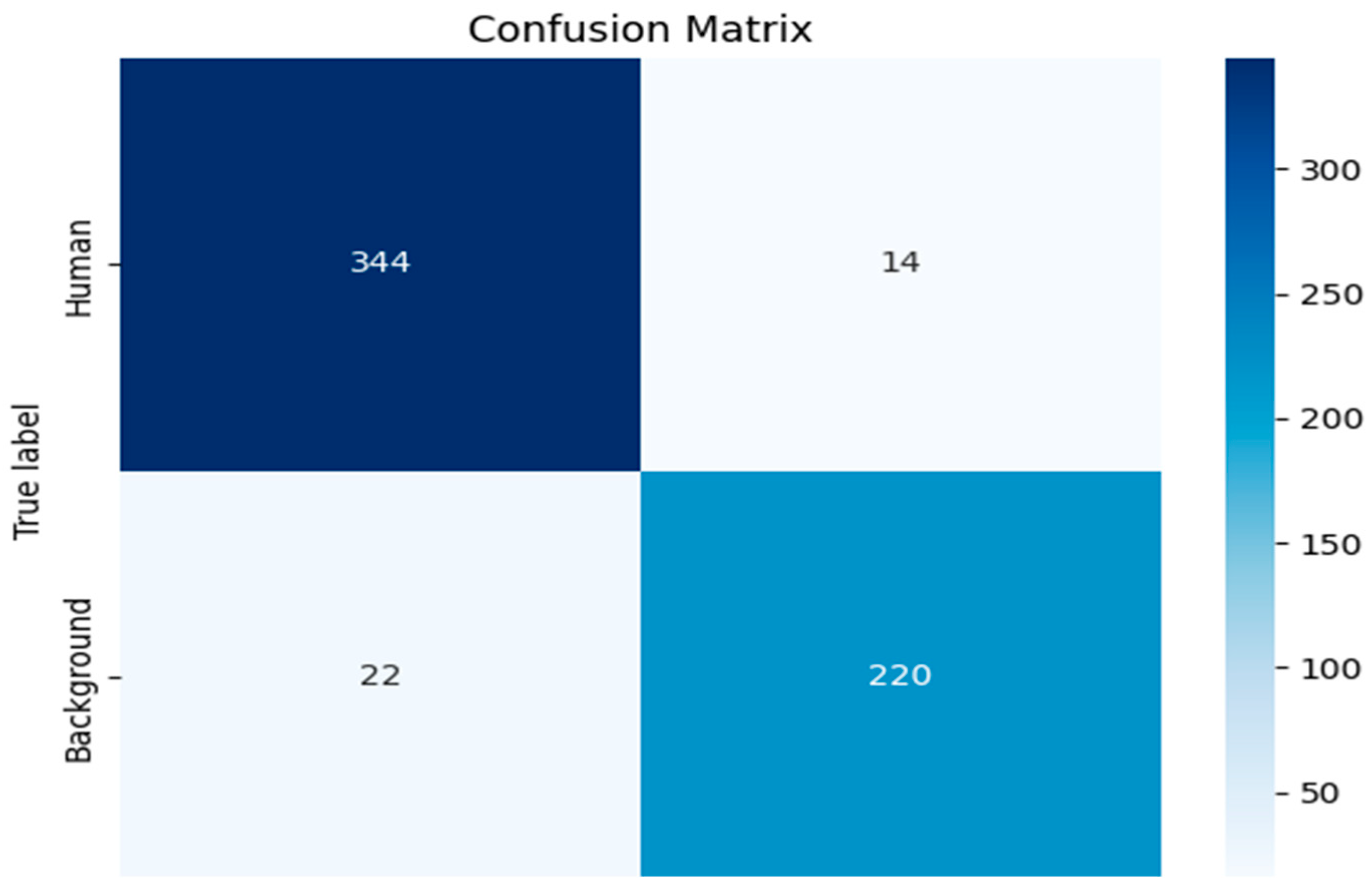

Figure 7 shows the confusion matrix revealed 344/358 true positives, with only 14 missed detections, mostly in cases of severe occlusion or very small bounding boxes (<10 px height). The precision–recall curve confirmed robust performance, with an optimal confidence threshold of 0.57.

3.5. Illustrative False-Positive and False-Negatives Cases

To better illustrate the limitations of the trained YOLOv8X detector,

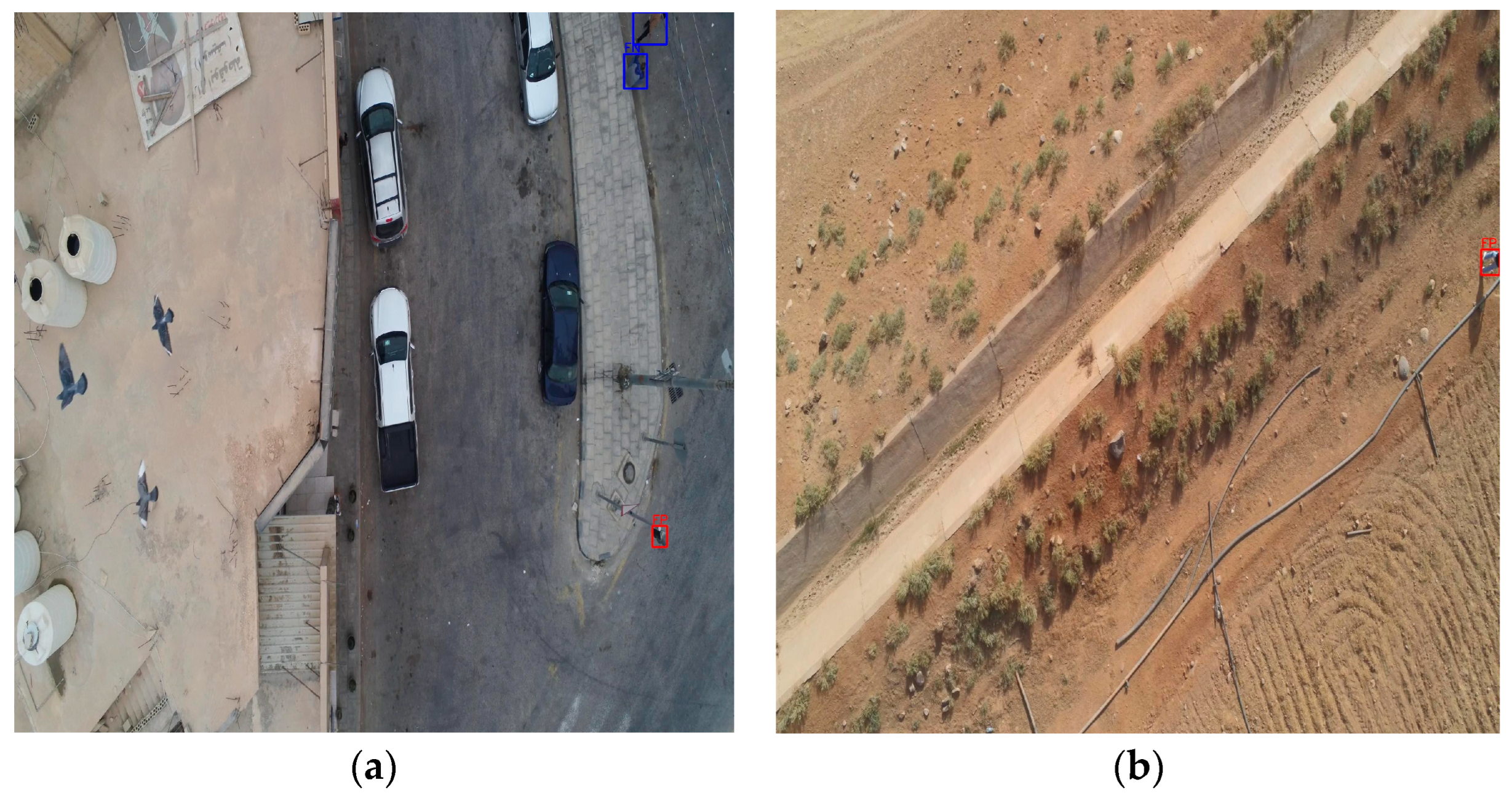

Figure 8a,b present sample cases of false negatives (FN) and false positives (FP) obtained from the test set. These examples highlight the conditions under which the model struggled, as well as situations where the detector correctly identified human features that were not captured in the ground-truth annotations.

Figure 8 shows two detection sample with error of false positive and false negative.

4. Discussion

This section discusses the implications of the experimental results, comparing them with previous research and highlighting the contributions, strengths, and limitations of the proposed approach. The discussion also outlines potential improvements and future directions for enhancing UAV-based search and rescue systems.

4.1. Advances over Existing Approaches

The proposed UAV cluster framework offers notable improvements over traditional single-UAV and conventional search and rescue methods. By integrating optimized routing, regional dataset adaptation, and high-performance detection models, the system achieves greater scalability, faster coverage, and significantly higher recall in identifying human subjects.

The integration of UAV clusters with AI-driven detection presented in this study demonstrates significant improvements compared to traditional SAR approaches and previously reported UAV-based systems. By employing 16 UAVs in a coordinated cluster, the system achieved 100% AOI coverage of a 17.6 km

2 region in under 40 min. In contrast, single-UAV approaches reported in prior studies [

9,

11] required several hours to achieve similar coverage, often with greater risk of missed areas due to battery constraints and operator fatigue. This highlights the scalability and efficiency of cluster-based UAV routing.

On the detection side, the YOLOv8X model achieved 97.6% recall and 98.4% mAP@0.50, outperforming previously published SAR benchmarks where recall typically ranges from 90–95% [

7,

18]. High recall is especially critical in SAR contexts, as missed detections can translate into missed lives. The incorporation of mosaic augmentation and transfer learning from VisDrone contributed to this performance, highlighting the importance of adapting datasets to regional conditions. Compared to works that relied on COCO or ImageNet pretraining, our approach better captured the challenges of arid landscapes, low-contrast conditions, and Jordan-specific terrain.

4.2. Contribution of the Jordan-Specific Dataset

One of the unique contributions of this work is the creation of a Jordan-specific SAR dataset, which directly addresses the issue of domain shift. Existing datasets such as UAV123 or Lacmus are valuable benchmarks but lack representation of arid and desert environments [

26]. When applied directly to Jordanian conditions, models trained on these datasets underperform due to differences in ground texture, lighting, and environmental features. By contrast, our dataset—collected across 12 diverse sites in Zarqa—includes desert, agricultural, industrial, and peri-urban settings, capturing the variability likely to be encountered in Jordan. This dataset not only improved detection performance but also ensures transferability of the system to real operations.

4.3. Trade-Offs in Routing Strategies

The choice of a lawnmower (boustrophedon) routing strategy reflects a balance between simplicity, reliability, and efficiency. While more adaptive approaches such as Voronoi partitioning or market-based CBBA allocation [

24] can dynamically redistribute UAVs based on workload, they often require more computational overhead and complex communication protocols. For a first deployment scenario, lawnmower routing provides a robust and predictable baseline. However, in highly dynamic environments (e.g., moving targets, rapidly changing AOIs), more adaptive strategies may prove advantageous. Future work should explore hybrid routing strategies that combine lawnmower sweeps for baseline coverage with dynamic reassignment for efficiency gains.

4.4. UAV Cluster Routing, Routing Advances, and Independence

A key contributor to the system’s strong performance is the UAV cluster routing and coordination strategy, which overcomes several limitations of single-UAV and non-coordinated approaches. Unlike traditional multi-UAV systems that rely heavily on continuous inter-UAV communication and synchronized updates—which can introduce delays and failure points in SAR missions, the proposed framework employs a lightweight handshake mechanism during mission initialization. After receiving its assigned sub-area and predefined lawnmower trajectory, each UAV operates almost entirely independently, dramatically reducing communication load, latency, and risk of cascading failures. This structure not only minimizes redundant overlaps and ensures gap-free, balanced coverage but also improves mission robustness in environments where connectivity is unreliable. Although the current study used homogeneous UAVs, the modular route-assignment logic and handshake protocol inherently support heterogeneous fleets, where UAVs with varying endurance and speed can be assigned sub-regions proportional to their capabilities. Together, these algorithmic advances demonstrate how decentralized coordination, independent execution, and flexible workload distribution can significantly enhance scalability, operational efficiency, and overall SAR performance compared to prior single-UAV or tightly coupled multi-UAV methods.

The proposed system also demonstrates strong computational efficiency, supporting real-time operation during SAR missions. The YOLOv8X model processes frames at approximately 252 ms per frame on a Tesla T4 GPU, enabling fast human detection as UAVs execute their routes. Combined with the decentralized routing strategy—where each UAV operates independently. This efficient interaction between rapid inference and independent multi-UAV coverage contributes to timely victim identification and improved operational responsiveness in large-scale SAR environments.

4.5. False Positives and False Negatives

The examples shown in

Figure 8 illustrate two representative failure modes of the detector. In the first case, the model produced a false negative when a human instance appeared against a low-contrast dark asphalt background. The limited contrast and small pixel footprint made the silhouette difficult to distinguish from surrounding textures, reducing the model’s confidence. The same image also produced a false positive, caused by background structures whose shapes resembled human contours when viewed from the nadir UAV perspective. Such cases highlight how cluttered or visually ambiguous environments can mislead silhouette-based detectors.

In the second example, the highlighted false positive was in fact a true human instance that was partially visible but omitted from the ground-truth annotations. The model successfully recognized the visible portion of the person, demonstrating its ability to detect subtle or incomplete human features. This observation emphasizes that some apparent false positives reflect annotation limitations rather than model errors, underscoring the difficulty of achieving perfectly exhaustive labeling in UAV-based SAR datasets.

4.6. Limitations of the Current Study

Although the proposed framework integrates a real-world human-detection model trained on an operational dataset collected across Jordan, the multi-UAV coordination results presented in this study are based on simulation rather than a physical drone-swarm deployment. This approach was necessary due to current regulatory restrictions on airspace access, communication-node availability, and the operational challenges of deploying and synchronizing many UAVs in uncontrolled environments. Therefore, the routing and coverage results should be interpreted as a validated scalability demonstration rather than evidence of full swarm operation. The next phase of this research, planned in collaboration with JODDB, will focus on implementing a real multi-UAV cluster with distributed communication, onboard inference, and coordinated mission execution. Future work will also explore robustness under adverse environmental conditions, latency-aware communication strategies, and dynamic re-tasking to support fully autonomous SAR operations.

Communication Range and Latency: The current implementation assumes reliable communication between UAVs and the central server. In real disaster scenarios, network disruptions could introduce delays or data loss. Relay UAVs or mesh networks may mitigate this issue.

Server-Side Processing: All detections were performed centrally. While this allows the use of computationally heavy models, it introduces latency and dependence on communication infrastructure. Hybrid approaches, where UAVs run lightweight onboard detection and forward proposals for central refinement, could provide a better balance.

Environmental Robustness: The dataset captured diverse Jordanian conditions, but environmental factors such as fog, heavy rain, or sandstorms remain challenging. Integrating thermal or multispectral imaging may improve robustness in such conditions.

Occlusion and Scale Limitations: As noted in the results, YOLOv8X struggled with severely occluded or extremely small targets. This is consistent with prior studies [

16,

17]. Incorporating super-resolution preprocessing or attention-based architectures could reduce these limitations.

4.7. Practical Implications for Jordan and Beyond

For Jordan, the proposed system addresses urgent needs in national disaster management, as highlighted by the 2018 Dead Sea tragedy [

30]. By providing a scalable and region-adapted SAR solution, this work contributes directly to improving preparedness and response capacity. Beyond Jordan, the system design—particularly the integration of cluster routing, region-specific dataset development, and AI-driven detection—can serve as a blueprint for other regions with similar vulnerabilities. With further refinement, the approach could also be extended to maritime SAR, wildfire monitoring, and cross-border disaster response collaborations.

Beyond detection, the UAV cluster framework enables continuous on-site monitoring, human localization through georeferenced bounding boxes, and generation of situational awareness maps. This shows that the framework is not only a detection system but a general-purpose SAR support platform.

4.8. Future Work

Building on the results presented here, future directions will include:

Field deployment trials in collaboration with Jordanian Civil Defense to validate performance under real disaster conditions.

Exploration of adaptive altitude control and super-resolution preprocessing to address scale and occlusion challenges.

Integration of thermal and multispectral sensors for enhanced robustness in fog, rain, or low-light scenarios.

Use of reinforcement learning for swarm autonomy, enabling UAVs to dynamically adapt their coverage and coordination strategies in changing environments.

Integration of advanced communication systems—such as Wi-Fi, LTE, or multi-hop mesh networks—to support low-latency connectivity, coordinated decision-making, and real-time on-board or edge-server inference.

In conclusion, this research provides both a practical contribution to national disaster management in Jordan and a generalizable framework for deploying UAV clusters with AI-driven detection in global SAR contexts. By bridging the gap between academic innovation and operational needs, it lays the foundation for faster, more reliable, and life-saving SAR missions.