1. Introduction

Photovoltaic power generation has proven to be one of the most prospective substitutes for fossil fuels. Cheap and efficient photovoltaic (PV) systems are necessary for the utilization of solar energy [

1]. The photovoltaic array is a collection of PV modules that generates electricity from sunlight. The current–voltage (I-V) characteristic curves of a PV module are nonlinear and strongly depend on environmental parameters such as solar radiation and temperature. Thus, maximum power point tracking (MPPT) is required for effective operation of a photovoltaic system.

Accurate characterization and parameter estimation for PV systems are activities of high importance in their design and assessment [

2,

3]. Reliable prediction models which reproduce the current–voltage characteristics of PV systems are also useful to evaluate their performances [

4]. There have been a number of models developed for PV cells including physical models and empirical models [

5,

6]. The model complexity, inputs, and estimation algorithms need to be taken into account when selecting the model, and are not trivial. However, with fine models there may be large errors in, for example, the estimation of model parameters and performance numbers such as efficiency and energy yield. Such an issue is especially critical in accurately evaluating the feasibility of large-scale PV investment. PV is the key to sustainable energy transitions as well as efficient, environmentally friendly, and economically viable power generation in many applications [

7,

8].

Among the many benefits of PV systems are their dependability, low maintenance requirements, and ease of use [

9]. This rule is intended to provide consideration of the property characteristic data for the design of PV systems. Photovoltaic systems display a nonlinear relationship between current and voltage characteristics. This is influenced by environmental factors such as temperature and solar irradiation. With the rapid expansion of photovoltaic systems, the parameters of the PV arrays must be evaluated to obtain accurate evaluations of their performance. Early and correct fault detection reduces energy losses, which is highly critical to have precise these days [

10].

That is why parameter estimation optimization techniques are important in calculating parameters for PV models. They achieve this by tuning model parameters to fit the observed behavior and minimizing the error between simulated and experimental current–voltage (I-V) characteristics. Traditional optimization methods include analytical approaches, fitting methods, and numerical methods, such as Newton-based algorithms [

11]. However, traditional methods tend to have many limitations in effectively coping with the highly nonlinear, multimodal, and multivariable character of bounded PV parameter estimation tasks, such as the influence of initial parameter estimates, susceptibility to local optima, and convexity and differentiability of the objective function. To address these difficulties, it has become popular to use natural process-based optimization metaheuristics. Some of these population-based stochastic optimization methods are Genetic Algorithms (GA), Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO), Differential Evolution (DE), and novel algorithms [

12,

13,

14] such as the opposition-based exponential distribution optimizer (OBEDO) need no gradient information and can perform global searches, trading off exploration and exploitation to prevent the algorithm from prematurely converging to one of the local minima [

15].

Several optimization techniques have been used for parameter estimation in PV models such as WOA (Whale Optimization Algorithm), GA (Genetic Algorithm), BBO (Biogeography-Based Optimization), ALO (Ant Lion Optimizer), and the recently developed BKA (Black-Winged Kite Algorithm) [

16,

17,

18].

Recently, several studies have revisited the PV parameter identification problem with a focus on improving both accuracy and computational efficiency. A hybrid analytical–metaheuristic framework has been proposed in which the diode ideality factor, saturation current, and photocurrent are obtained from closed-form relations, while only the series and shunt resistances are optimized using a suite of population-based optimizers, thereby reducing the decision space from five to two parameters without degrading the quality of the I-V/P-V fit [

19]. In a complementary direction, a hybrid secant–Newton–Raphson procedure combines an initial secant-based estimate of the series resistance with a refined Newton–Raphson iteration, yielding a simple and fast numerical scheme that remains accurate under varied irradiance and temperature conditions [

20]. To further enhance the search capability of evolutionary algorithms, an enhanced differential evolution (EDE) strategy with stage-specific mutation and crossover control has been developed, achieving very low RMSE values for single-, double-, and triple-diode models of several benchmark cells and modules by adaptively balancing exploration and exploitation during the optimization process [

21].

Beyond purely algorithmic improvements, recent works have also refined the underlying PV models and the way parameters are extracted. A voltage-dependent single-diode model has been introduced in which all five parameters are allowed to vary with operating voltage; by segmenting the I-V curve into three regions and applying a hybrid analytical–numerical identification in each segment, this SDMvd formulation significantly reduces the modeling error compared with conventional voltage-independent single-diode models [

22]. A metaheuristic based on the Improved Dwarf Mongoose Optimization (IDMO) algorithm has been proposed for parameter extraction of single-, double-, and triple-diode models as well as module-level generators, demonstrating consistently lower RMSE and extremely small run-to-run variability relative to other state-of-the-art approaches [

23]. In parallel, a systematic comparison of several analytical and iterative schemes for single-diode parameter estimation has shown that both categories can reproduce the I-V and P-V characteristics with high fidelity under STC, while also highlighting that some classical analytical formulas underestimate the power around the MPP [

24].

These algorithms have certain advantages as well as disadvantages when applied to complex nonlinear PV parameter estimation problems [

25]. GA and some other traditional methods, leveraging crossovers and mutations, understand the PV properties well and maintain the diversity of their populations. While they are efficient and appropriate for large-scale search, they generally suffer from slow convergence and can get trapped in a local minimum [

26]. Although BBO and ALO are capable of searching the space and clustering, keeping the population in balance, they are not robust when optimizing process, and can easily result in low and premature convergence in the complex problems. WOA is a simple method and accomplishes considerable exploration at the early stage of the search, but it is less efficient in exploiting the search space, so it results in poor solutions [

19]. These recent advances confirm the importance of combining physically informed formulations with robust optimization, but they also indicate that there is still room to design new metaheuristic frameworks that offer high accuracy across single- and multi-diode models, reduced computational cost, and robust performance under diverse operating conditions motivating the BKA-based approach proposed in this work.Compared with existing BKA-based or biology-inspired approaches, the present work makes three specific contributions. First, it provides a unified and statistically rigorous assessment of the BKA on single-, double-, and triple-diode PV models using the same experimental dataset and search conditions, whereas most previous studies consider only a single model or synthetic benchmarks. Second, the BKA is systematically benchmarked against several state-of-the-art metaheuristics using multiple performance indicators (RMSE, absolute current and power errors, convergence behavior, stability, and computational cost), revealing a distinctive combination of accuracy and robustness that has not been reported in earlier PV parameter-identification studies.

However, the proposed BKA manifests numerous improvements in comparison. The Black-Winged Kite Algorithm uses two movements (exploration and exploitation) which are inspired by the hunting and migration behaviors of black-winged kites. Its exploitative behavior provides robust searching behavior in promising areas, and its global search mechanism helps to explore the whole search space, which may enable escape from local optimum. The diversity mechanism guarantees the uniformity and efficiency of the searching process, which can achieve faster convergence and higher accuracy in parameter estimation. In addition, the BKA needs fewer control parameters, and it is much easier to use when a misconfiguration occurs.

Despite these advances, existing BKA-based PV studies and other bio-inspired approaches typically address only a single PV model or rely on heterogeneous datasets, parameter bounds, and stopping criteria. As a result, it is still difficult to assess in a fair and systematic way how the BKA behaves as model complexity increases from single- to double- and triple-diode formulations, or how its convergence speed, run-to-run variability, and computational cost compare with alternative metaheuristics under identical conditions. There is therefore a clear need for a unified and statistically rigorous assessment of the BKA for PV parameter identification that can provide practical guidance to designers of PV modeling and MPPT algorithms.

To address this gap, the present work makes the following scientific contributions: (1) We formulate parameter estimation for the single-, double-, and triple-diode PV models as a unified optimization problem with consistent, physically meaningful parameter bounds derived from the RTC France silicon cell data and prior PV studies. (2) We adapt the standard single-objective BKA to this unified framework and perform a statistically rigorous evaluation over 30 independent runs per model, reporting not only the best RMSE but also the mean, worst-case, standard deviation, and absolute errors in current and power, together with convergence behavior and CPU time. (3) We carry out a head-to-head comparison with several widely used metaheuristics (GA, WOA, TSA, BBO, ALO, and DA) under the same population size, iteration budget, and search space, and we show that BKA achieves comparable or lower RMSE with fewer control parameters and competitive runtime across all three PV models. Collectively, these results clarify under which conditions BKA is advantageous for PV parameter estimation and establish a benchmark reference for future hybrid or multi-objective extensions.

2. Modeling of the PV Cell

A photovoltaic cell is a device that absorbs the light of the sun and converts it to electricity. There are two general methods for creating electrical power from the sun: photovoltaic and solar thermal. Photovoltaic cells promise numerous advantages including very good reliability. They do not make noise and vibration as in solar thermal systems [

27]. Some of the key parameters to measure for PV systems are maximum power output, short-circuit current, open-circuit voltage, fill factor (FF), and efficiency. The MPP is shown in both I-V and P-V curves on a PV cell or module and it indicates one point of maximum power output of the cell or module [

28]. The MPP depends on the operating conditions of irradiance and temperature of sunlight; consequently, MPPT algorithms are required to be employed in order to continually maximize the extraction of the incident energy.

Photovoltaic models can be classified into two types in general: the physical model and the empirical model. In the former approach, the operation of the photovoltaic cell has been described based on the properties of the semiconductor material, electric circuit elements, and the geometry of the construction. By contrast, physical models draw current and voltage measurements and then fit mathematical equations that explain how a cell is going to behave. Empirical models are often preferred for MPPT algorithm design and real-time calculation due to their simplicity and cost-effectiveness [

29]. The five parameters in the empirical model of the single-diode model are the saturation current (

), the ideality factor (

n), the series resistance (

), the shunt resistance (

), and the photocurrent (

). The prediction accuracy for the model handling also gets further improved today by applying a double-diode model and triple-diode model. These models incorporate additional parameters to handle the effects of recombination loss and non-ideal diodes [

16]. Therefore, they are suitable for detailed modeling and performance analysis at various conditions and states. The empirical model serves for characterizing behavior by I-V factorization. Because of the advantages of easy-to-use and simple in form of the empirical model, compared with physical models, it is more suitable for analysis and implementation of MPPT algorithm.

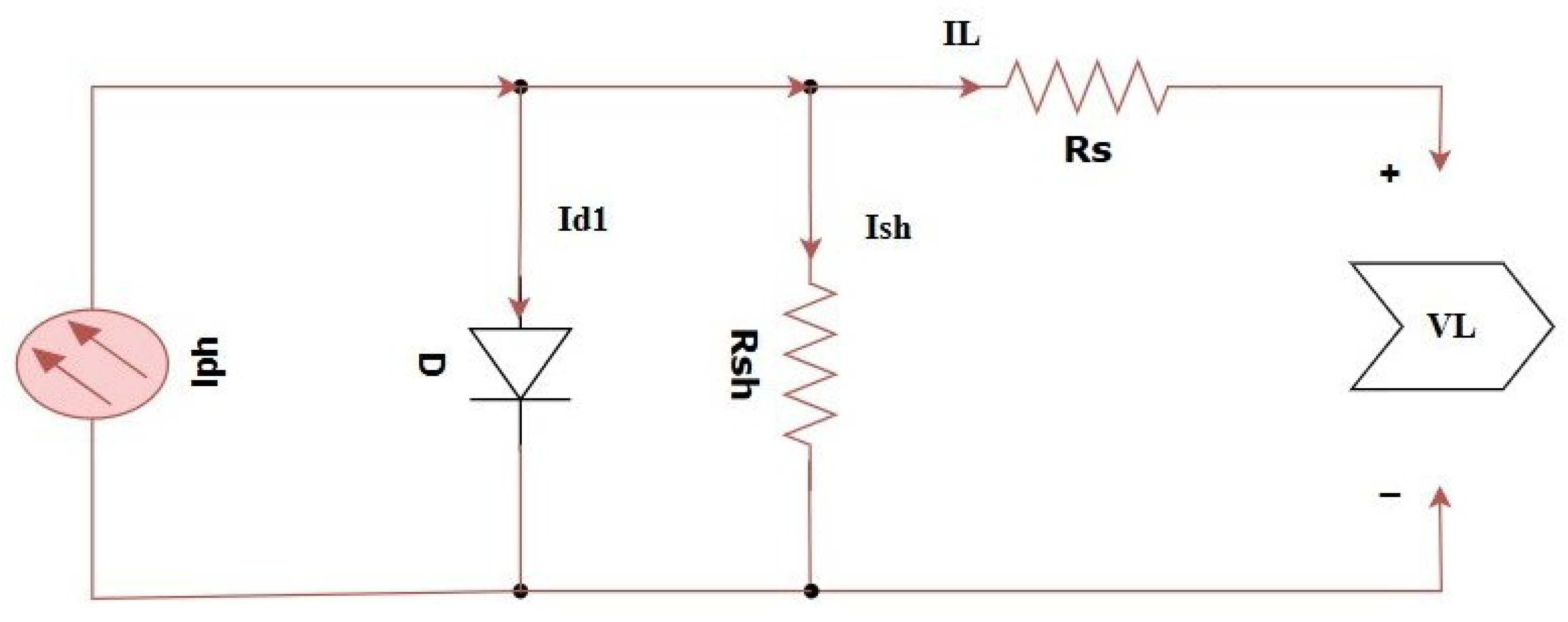

2.1. Single Diode Model (1DM)

The so-called single-diode model is a simplified equivalent circuit used to describe the I-V characteristics of PV cells. It includes, as described above, a current source

representing the photocurrent, a diode

D representing the p-n junction, and various resistors that account for losses. Apart from these, the 1DM is introduced, containing the

series resistance to model losses in the cell and the

parallel resistance to model the shorting of the cell. As a result,

Figure 1 is a 1DM circuit comprising equivalent current source

representing the photocurrent, a diode, and the so-called voltage–current shunt resistance

with the resistor

[

16].

Equations (1)–(4) follow the standard single-diode photovoltaic model widely used in PV parameter identification studies [

30,

31].

Equation (

1) expresses the output current

of the single-diode model as the balance between the photocurrent, diode diffusion current, and shunt leakage current.

where

denotes the photocurrent generated by the cell, and the shunt current branch is modeled in Equation (

2), given by the following equation:

denotes the diode current and is modeled in Equation (

3) using the classical Shockley diode expression to represent recombination effects.

where

is the reverse saturation current,

is the output voltage,

is the ideality factor, and

is the thermal voltage.

K is the Boltzmann constant

J,

q is the elementary charge

C, and

T is the temperature in Kelvin. Combining Equations (1)–(3) gives a comprehensive expression for the output current as shown in Equation (

4):

Five unknown parameters are determined in addition to the known ones: , , , , and n.

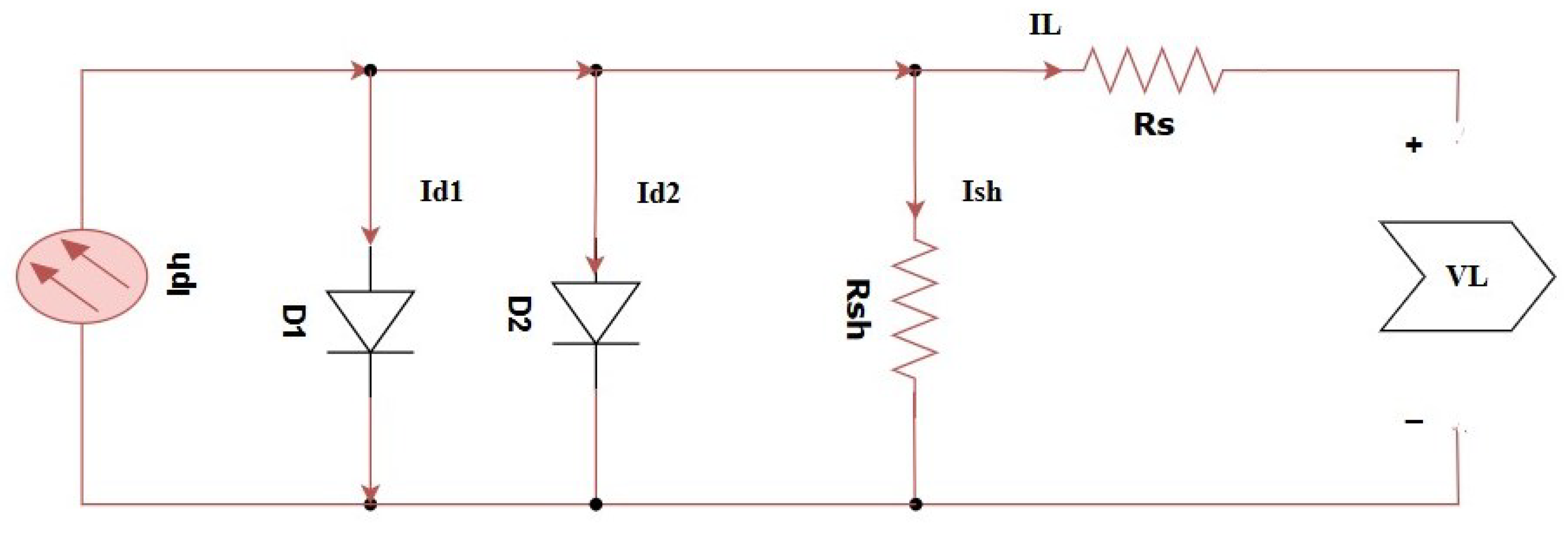

2.2. Double Diode Model (2DM)

The double-diode model is an expansion of the single-diode model, designed to accurately describe I-V characteristics of photovoltaic cells, especially when they are not ideal.

Figure 2 represents this kind of model. It consists of two diodes [

16]. The major equations are as follows for the double-diode model:

The output current

for the double-diode model can be expressed by Equation (

5):

where

and

are the reverse saturation currents,

is the output voltage,

, and

T is the temperature in Kelvin. Diode

models the ideal behavior of the p-n junction and diode

accounts for recombination losses within the junction.

and

are the ideality factors for each diode.

2.3. Triple-Diode Model (3DM)

The triple-diode model is a valuable tool for achieving higher accuracy in modeling PV cells. It not only meets the high-precision needs of simulator designers but also has served as an excellent base to improve upon modeling [

32].

Figure 3 represents this kind of model.

The output current

for the three-diode model [

16] is given by Equation (

6):

Diode 1 () models the diffusion current. Diode 2 () accounts for recombination current. Diode 3 () represents leakage currents due to grain boundaries and other imperfections. , , and are the ideality factors for each diode.

2.4. Problem Formulation

The procedure for searching the unknown parameters for all photovoltaic cell models and modules is referred to as optimization, while the calculated data will be driven to the measured values through the optimization process that minimizes the difference and involves the characteristics of the models. The objective function used to estimate the optimal model parameters is defined in terms of the root mean square error (RMSE), as given in Equation (

7) [

33]:

where

N represents the collected experimental data,

and

are the solution vector

X, and

is the error function, which is defined for the different PV models in the following manner [

16]:

2.4.1. For the Single Diode Model

The output current for the single-diode model is expressed in Equation (

8):

2.4.2. For the Double Diode Model

For the double-diode model, the output current is defined by Equation (

9):

2.4.3. For the Triple Diode Model

The output current for the triple-diode model is defined in Equation (

10):

The objective function is the root mean square error (RMSE) for 1DM, 2DM, and 3DM:

4. Results and Discussion

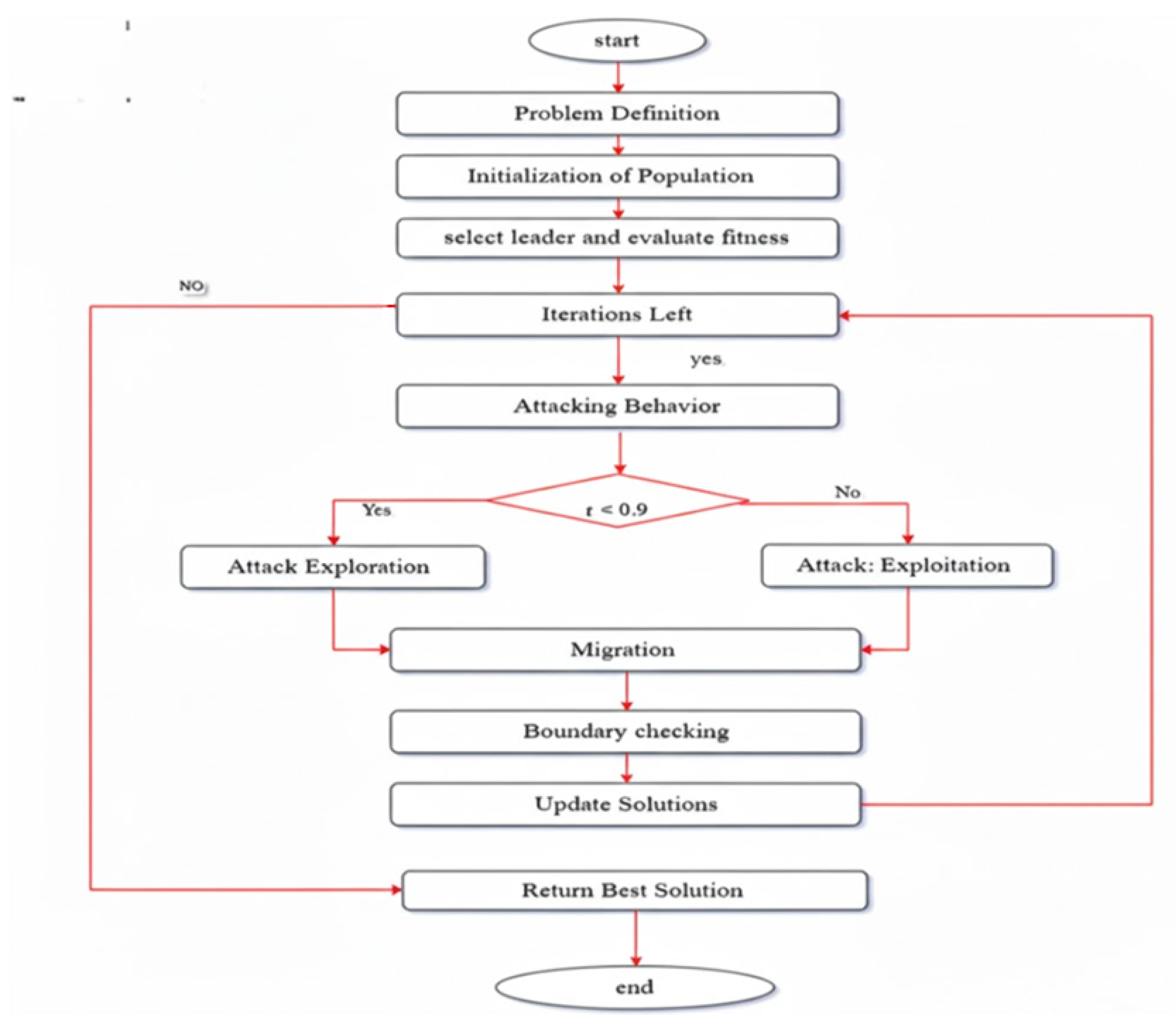

This section uses the Black-Winged Kite Algorithm (BKA) to estimate the characteristics of three photovoltaic (PV) versions of the RTC France solar cell that are available. The single-diode model (1DM), two-diode model (2DM), and three-diode model (3DM) circuits are used to describe the PV modules. Since the BKA has a stochastic character, its performance in estimating unknown parameters was examined by running the method 30 times separately for each model. Using a maximum of 1000 iterations and a population size of 50, 26 pairs of voltage and current samples were obtained from a 57 mm diameter RTC France silicon solar cell at 33 °C as well as 1000 W/m

2 solar irradiance in order to extract the unknown parameters of three models (1DM, 2DM, and 3DM). A variety of metrics are used to examine the performance, including the worst (max) RMSE, the best and average (mean) RMSE, and the standard deviation (STD). Additionally, a convergence curve was used to compare each algorithm’s rate of convergence, and the computational cost was assessed in terms of the amount of time needed to get the best result. In this study, we use an analytic method that derives the I–V model parameters from the manufacturer’s datasheet values (

), adopting the same RTC France cell data reported in [

35].

For each PV model, the proposed BKA is executed with the same population size and iteration budget (50 individuals and 1000 iterations). The initial population is generated uniformly within the parameter bounds listed in

Table 1. The internal control parameters of the BKA follow the configuration recommended in its original description: the attack-intensity coefficient is initialized at

and decreased over the iterations to shift the search from exploration to exploitation, while a migration term together with a Cauchy-distributed local perturbation around the current best solution is used to diversify the kites’ positions. For a fair comparison, all benchmark optimizers are run under the same population size, maximum number of iterations and search space as BKA, and their remaining algorithm-specific coefficients are kept at the standard default values given in their original papers.

The parameters’ lower and upper limits (LLs; ULs) for each of the three models are shown in

Table 1.

The lower and upper bounds reported in

Table 1 were selected to be physically meaningful for the RTC France silicon cell and consistent with the ranges commonly adopted in the PV parameter-estimation literature. In particular, the bounds for

are centered around the measured short-circuit current; the diode saturation currents are constrained to small positive values that match typical single-, double-, and triple-diode models; the series and shunt resistances are restricted to realistic intervals (low series resistance and high shunt resistance); and the ideality factors are limited to a range compatible with semiconductor device physics. These constraints ensure that the search space encompasses all physically plausible solutions while excluding non-physical parameter combinations.

Every experiment was carried out on a PC running 64-bit Windows 10 Professional, with 32 GB of RAM, and a 2.40 GHz Intel(R) Core(TM) i7-4700MQ CPU. Every algorithm was implemented using MATLAB R2019a.

4.1. One-Diode Model (1DM)

The objective for the single-diode model (1DM) is to estimate five unknown parameters:

,

,

,

, and

n.

Table 2 shows the results of the BKA algorithm for estimating these parameters and compares them with alternative approaches for determining the optimal RMSE.

The BKA algorithm achieved the best RMSE of

, as indicated in bold in

Table 2. The BKA is comparable to TSA, GA, WOA, and BBO, and outperforms the other algorithms across all performance metrics. This superiority is attributed to the exploitation improvement mechanism in the BKA, which enhances the search around the best-so-far solution and accelerates convergence compared to other algorithms.

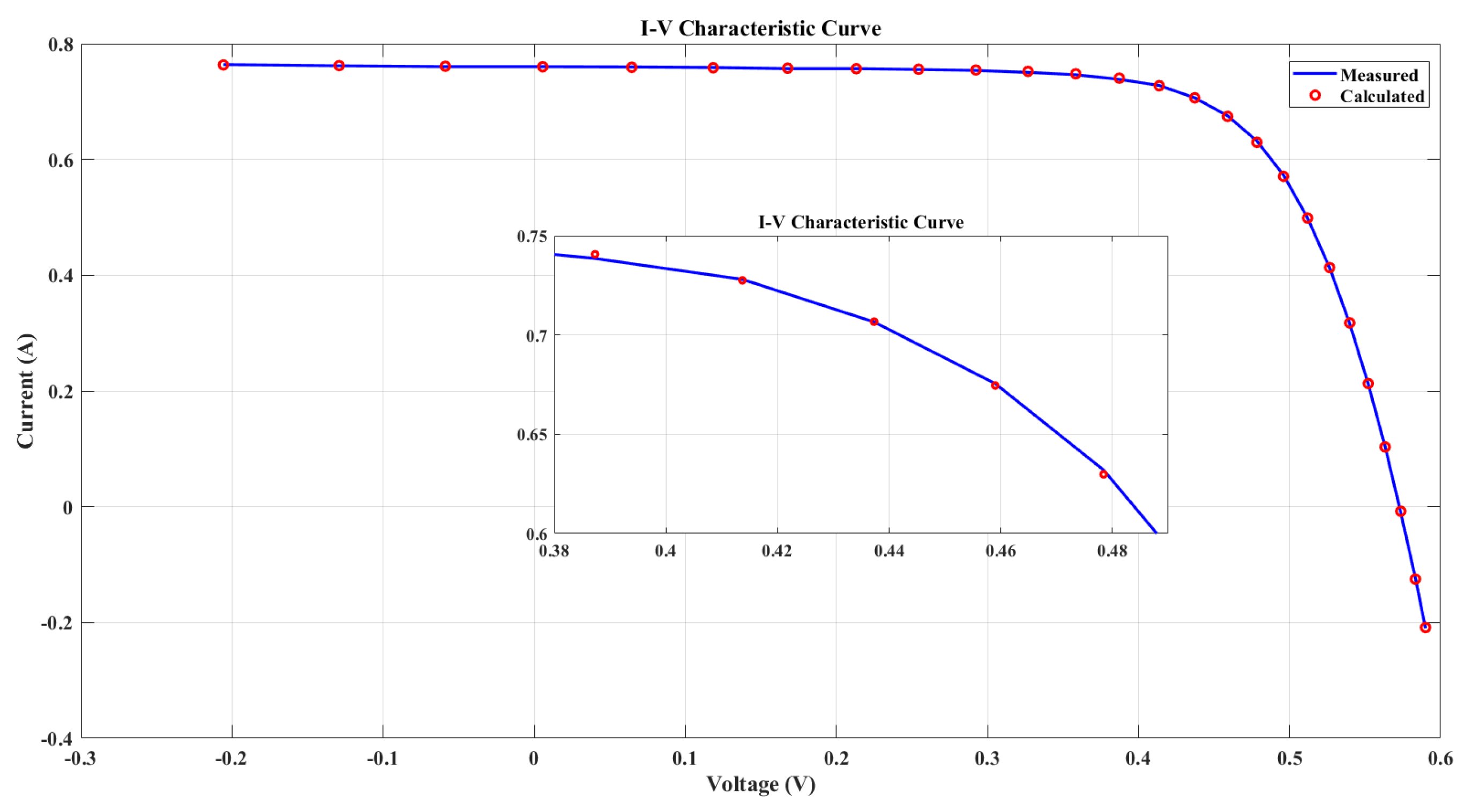

The best values of the identified parameters for the 1DM adopted models of the RTC France silicon solar cell are presented.

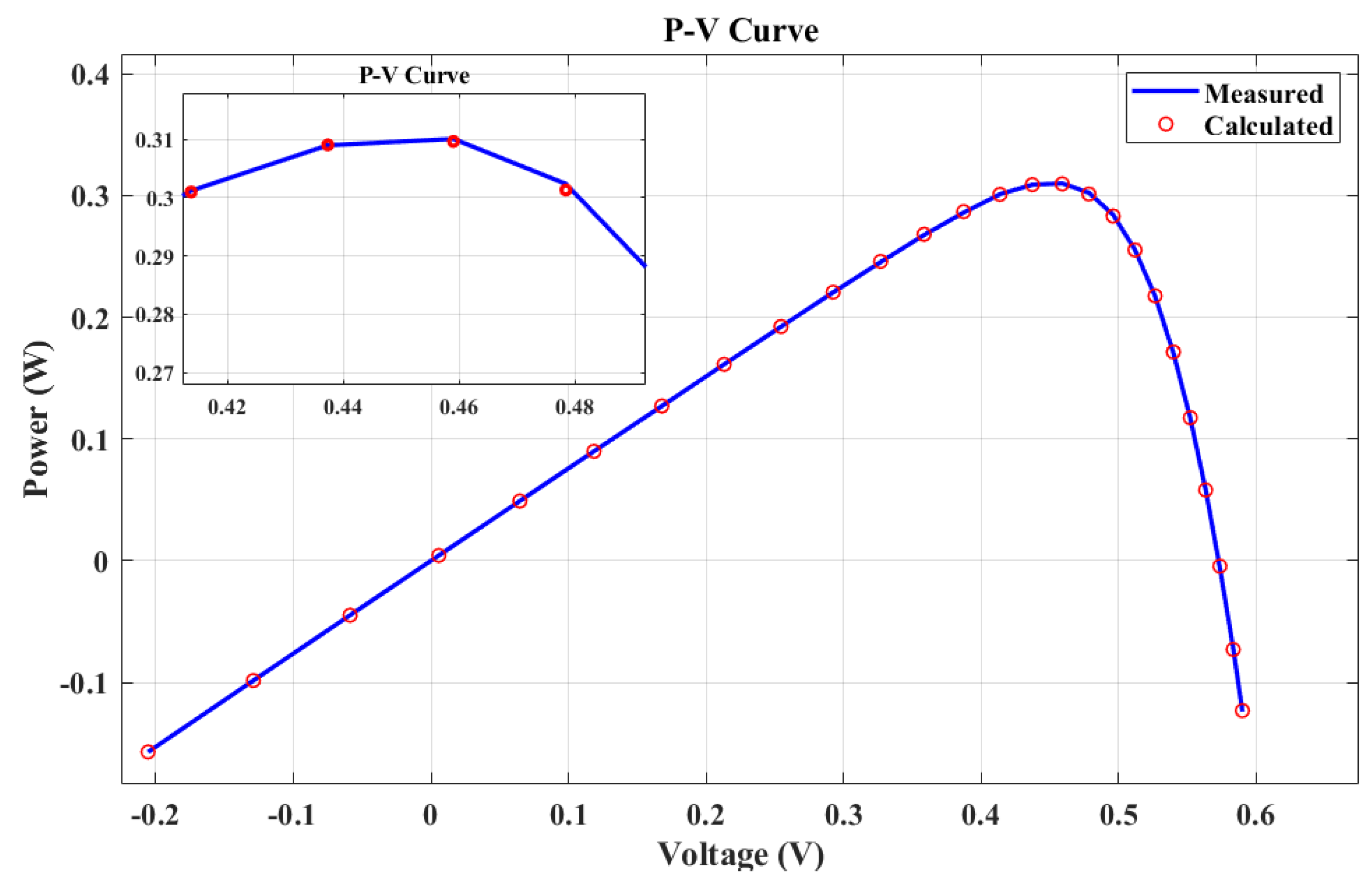

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 illustrate the I-V characteristic of the solar PV cell, where

and

are the current and power calculated using the BKA, and

and

are the measured current and power, respectively. The simulation results closely match the measured data, as shown in the figures, confirming the efficacy of the BKA-based 1DM parameter estimation. The output current and power relative to the measured voltage can be determined after the model parameters for the RTC France silicon solar cell have been identified.

The statistical results from the BKA and other algorithms, including BBO, ALO, DA, WOA, TSA, and GA, are shown in

Table 3 to assess the robustness and dependability of the suggested method. The RTC France silicon solar cell’s 1DM statistical results include the lowest RMSE value (

), the average RMSE value (

), the worst RMSE value (

), the running time (CPU), and the standard deviation of the RMSE values (STD), indicating the algorithm’s reliability.

The statistical performance of the BKA for the 1DM is summarized in

Table 3, where the RMSE has a mean value of

and a maximum value of

. The most computationally efficient run required 999 iterations, with a CPU time of 7.8575 s and an RMSE standard deviation of

. These results indicate that, for the single-diode model, the BKA yields highly accurate and statistically consistent parameter estimates.

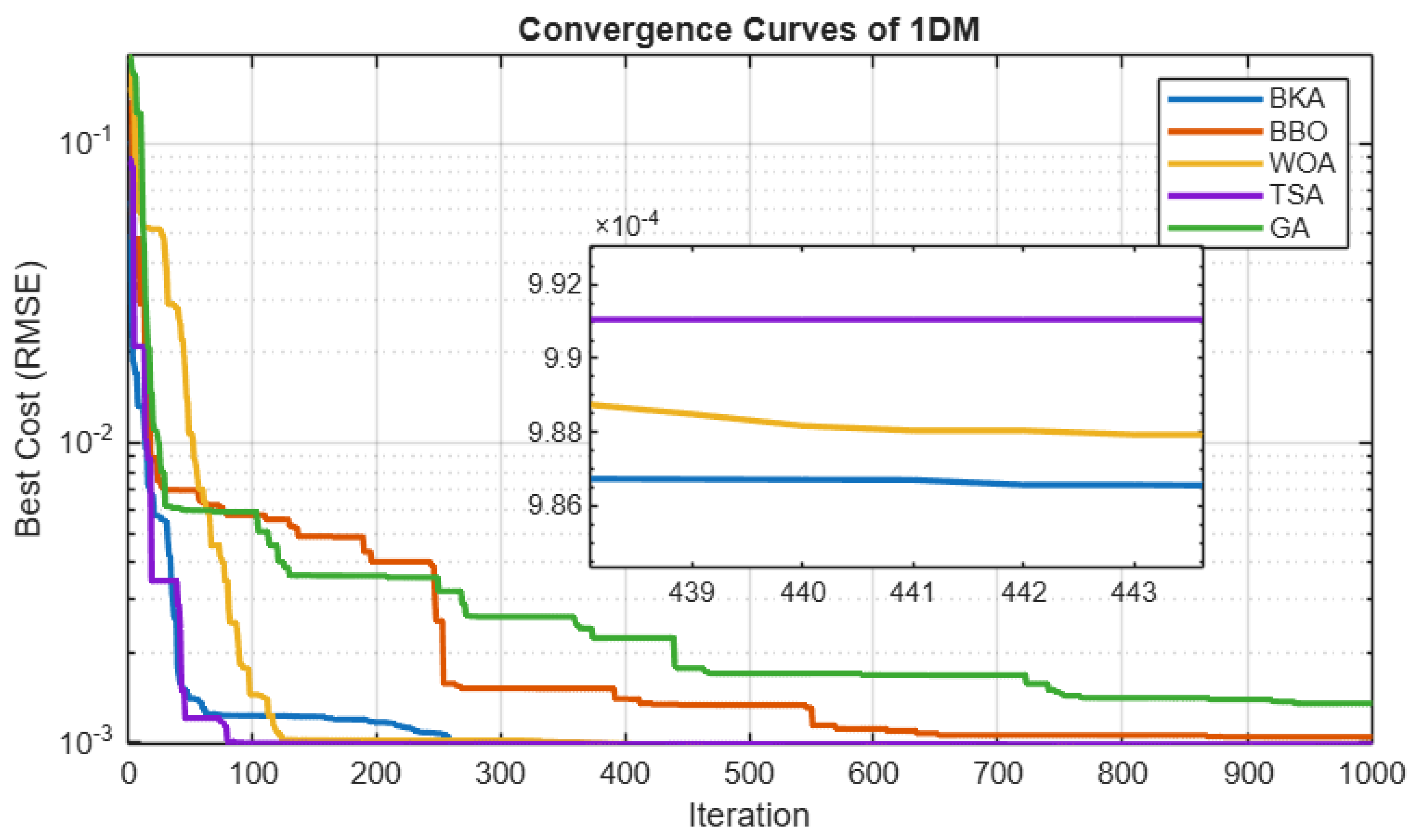

Figure 7 shows the convergence characteristics of the five algorithms for the 1DM. Among them, the BKA exhibits the fastest and most stable convergence behavior, maintaining a smooth descent toward the global optimum and reaching an RMSE on the order of

within the first few iterations. This rapid decrease in error demonstrates the BKA’s strong exploitation capability and its effectiveness in locking onto the optimal region of the search space.

By contrast, WOA and TSA show slower convergence rates and exhibit several plateaus that indicate stagnation. This behavior reflects weaker exploitation strategies and a tendency to linger in suboptimal regions before making further progress. Although BBO also converges, its trajectory displays noticeable oscillations, indicating a less stable search process and increased sensitivity to parameter settings. Among all the tested approaches, GA performs the worst. Its noisy convergence trajectory suggests poor consistency and premature convergence, and its convergence curve remains at a relatively high RMSE level throughout all iterations. This pattern is usually linked to insufficient population diversity and a higher likelihood of becoming trapped in local minima.

Overall, the results in

Figure 7 show that the BKA is superior in both convergence speed and solution stability for the single-diode PV model, and it achieves the lowest final RMSE value with minimal oscillations.

An alternative metric for comparing the effectiveness of the implemented algorithms is the convergence curve. The convergence curves for 1DM are shown in

Figure 7, and the BKA is clearly one of the more effective algorithms when compared to the others. Algorithms such as WOA, TSA, and BBO, on the other hand, show greater variability, with poorer worst-case RMSE values and significantly larger standard deviations. The GA, on the other hand, performs the poorest; its excessive unpredictability and noticeably higher RMSE values make it less dependable.

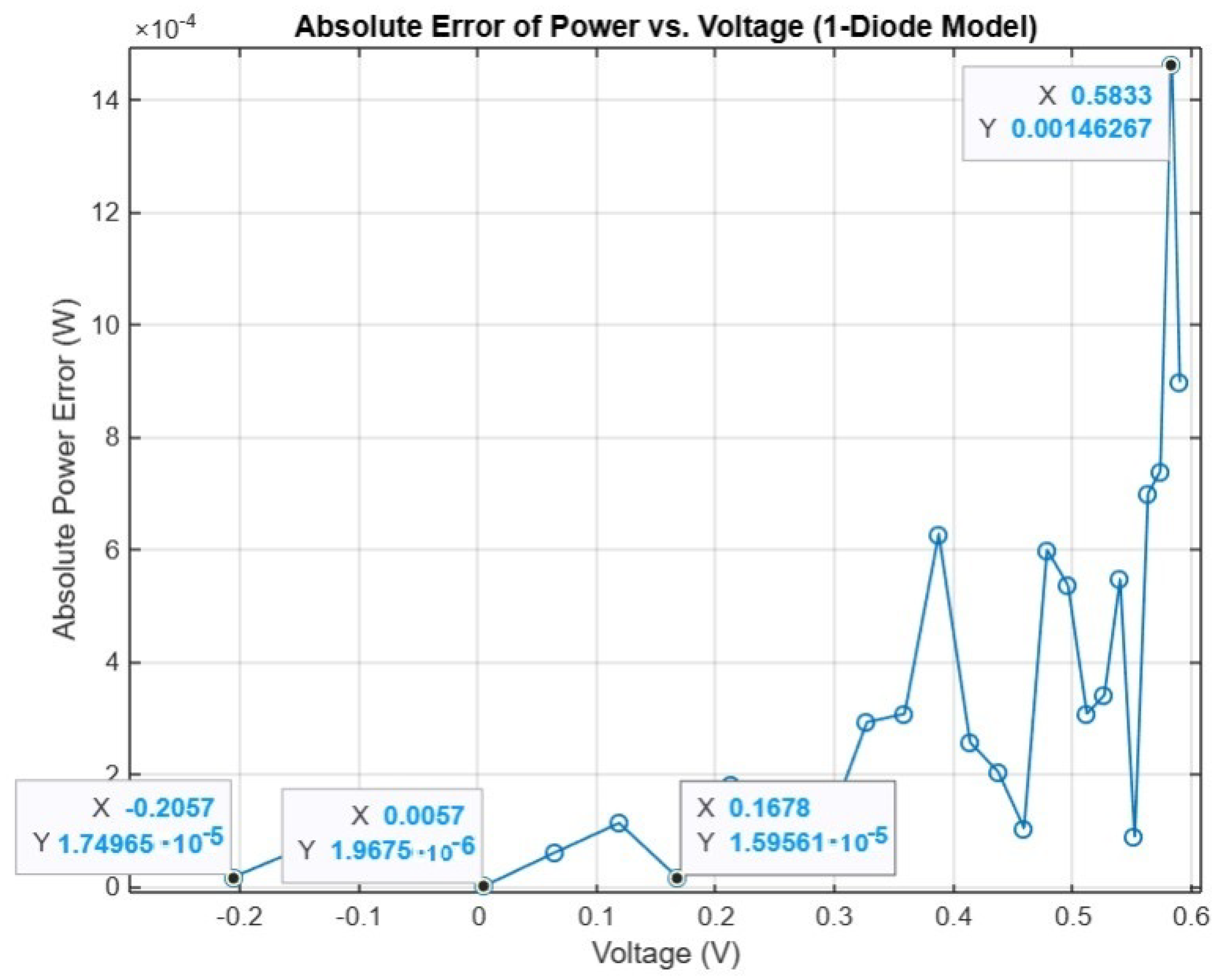

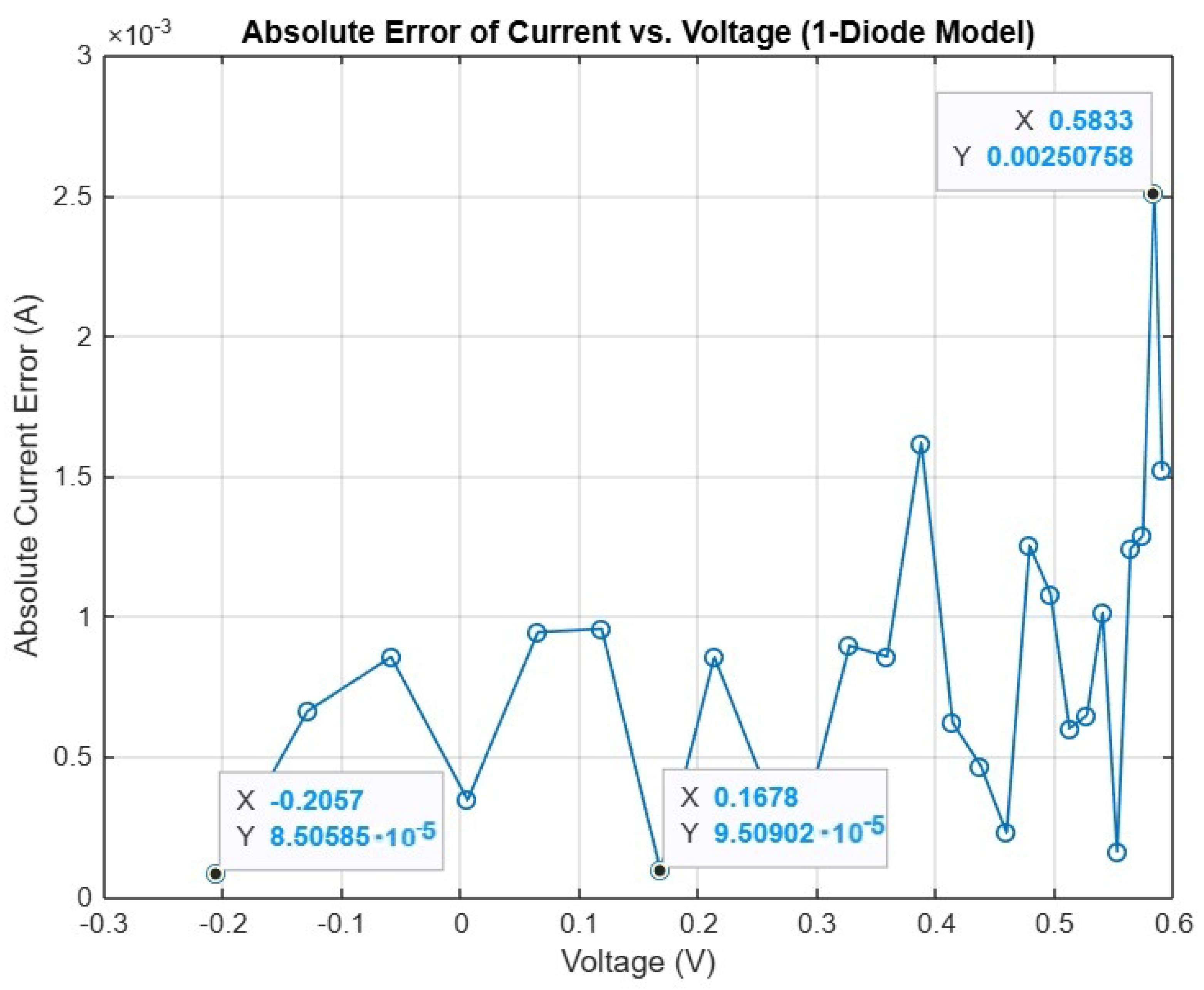

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 present the absolute power and current error distributions for the 1DM across the measured voltage range. The BKA achieves consistently low error values in both plots, with the minimum absolute power error reaching

W and the minimum current error reaching

A. The errors remain small over most of the operating region, increasing only near the open-circuit point where nonlinearities are strongest. These results confirm that the BKA maintains high fitting accuracy for both P-V and I-V characteristics, demonstrating strong reliability and numerical stability in parameter estimation.

All performance measures show that the BKA had the smallest standard deviation of RMSE at and had a significant lead over TSA RMSE . It had the lowest average RMSE of , approximately 9% less than its closest rival, TSA at , and clearly below WOA at . Regarding the minimum individual RMSE values, we obtained for the BKA, which is almost the same as WOA at . With respect to the processing time, the proposed algorithm converged in approximately 8.53 s, which is more efficient than BBO (15.36 s) and GA (6.76 s). WOA (3.14 s) performed slightly better in terms of speed, but its accuracy and stability were extremely low, leading to the conclusion about the good convergence speed.

4.2. Double-Diode Model (2DM)

For the double-diode model, the goal is to estimate seven parameters:

,

,

,

,

,

, and

. Accurate estimation of these parameters is crucial for modeling PV cell behavior under varying conditions. The BKA achieved the lowest RMSE of

, as highlighted in

Table 4, outperforming other contemporary optimization algorithms such as ALO, WOA, GA, TSA, DA, and BBO. The ranking based on minimum RMSE values confirms the BKA as the most effective method for parameter extraction in the 2DM context.

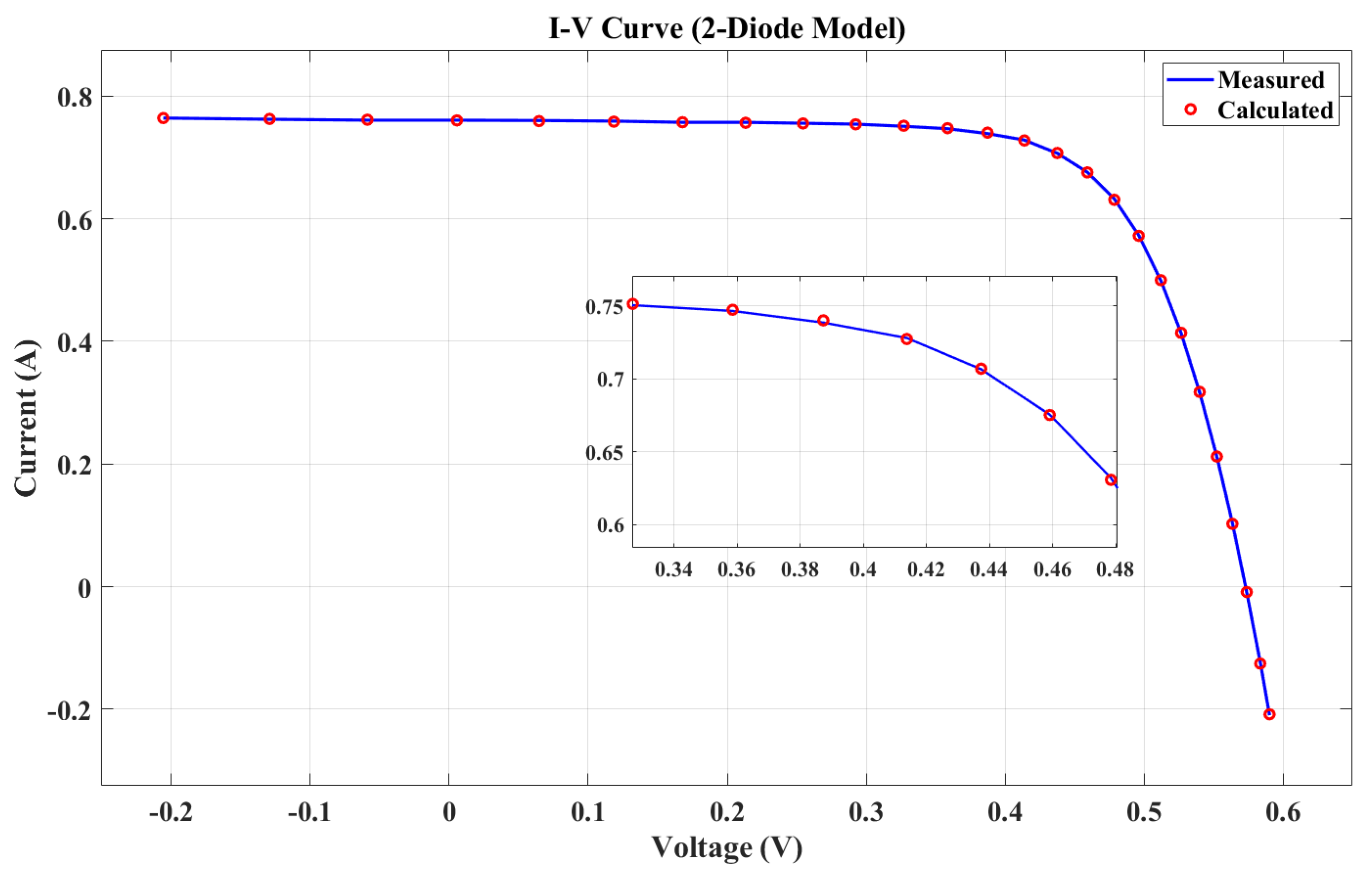

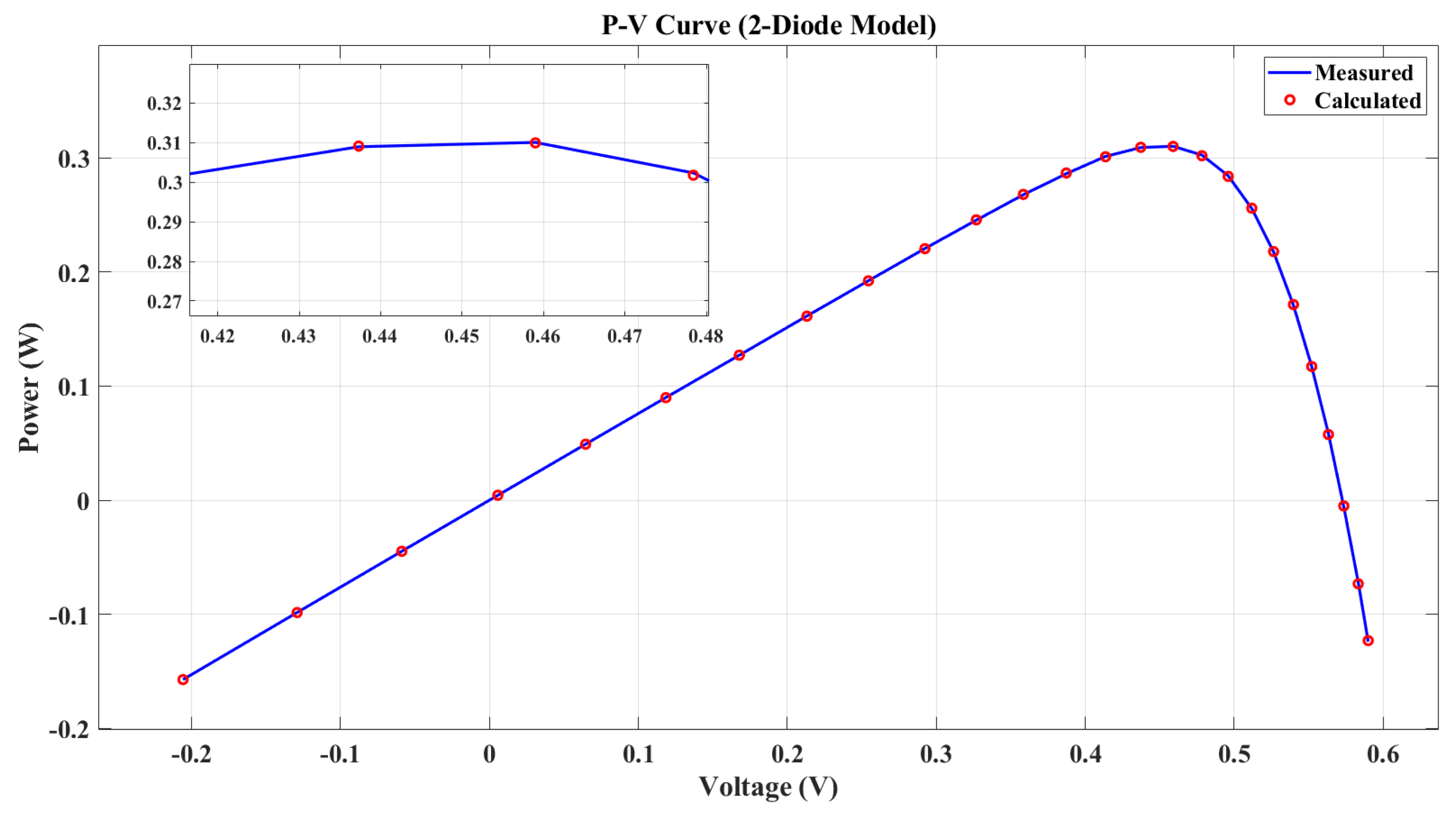

To validate the accuracy, the I-V and P-V characteristics were computed and compared with experimental data from the RTC France silicon solar cell.

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 illustrate the I-V and P-V characteristics of the 2DM solar PV cell.

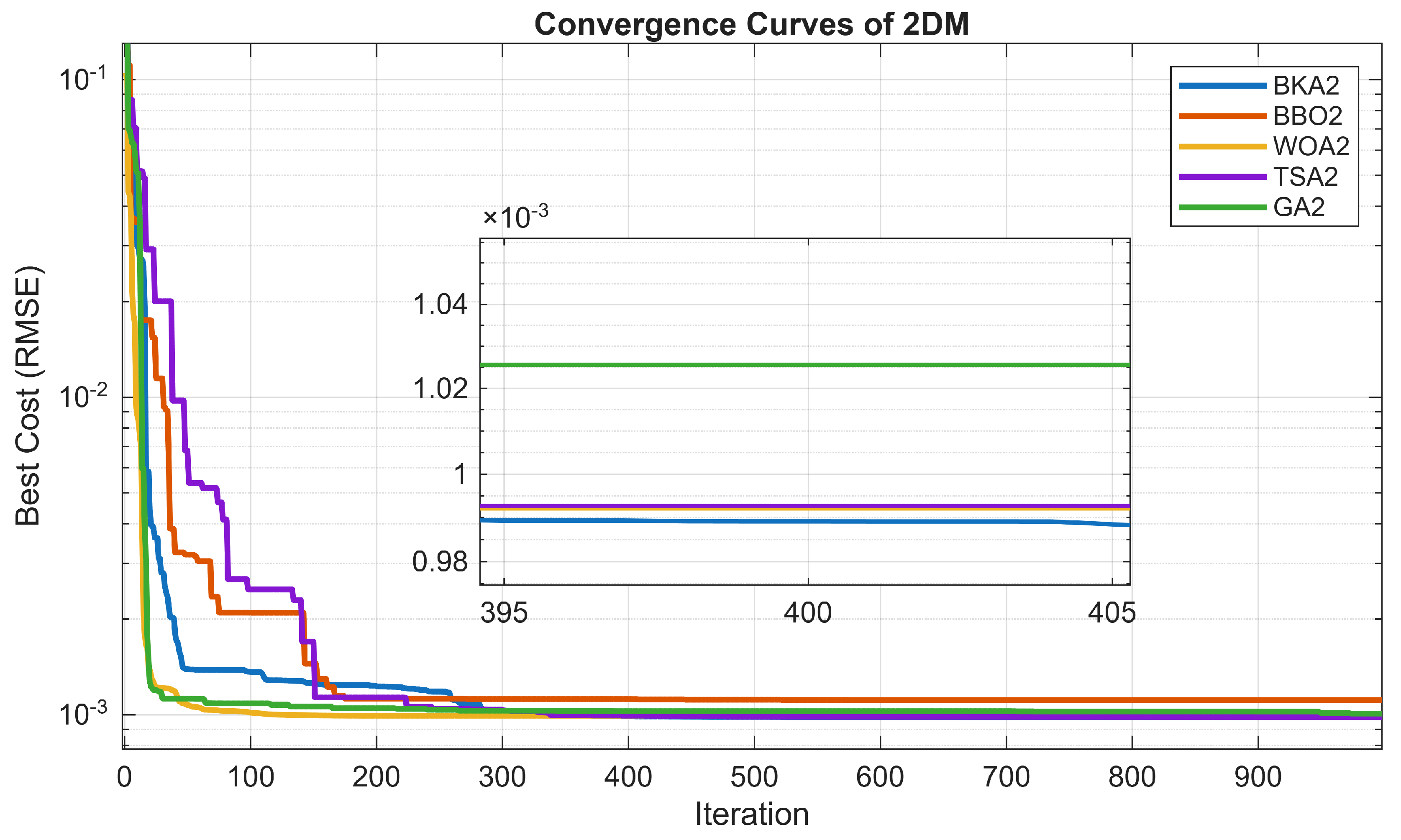

Algorithms such as TSA and WOA show greater variability, with poorer worst-case RMSE values and significantly larger standard deviations. The GA and BBO, on the other hand, perform the poorest; their excessive unpredictability and noticeably higher RMSE values make them less dependable. The convergence curves for the 2DM, based on the estimated parameters from the BKA with the best RMSE, are shown in

Figure 12. All things considered, the BKA successfully balances mathematics and precision.

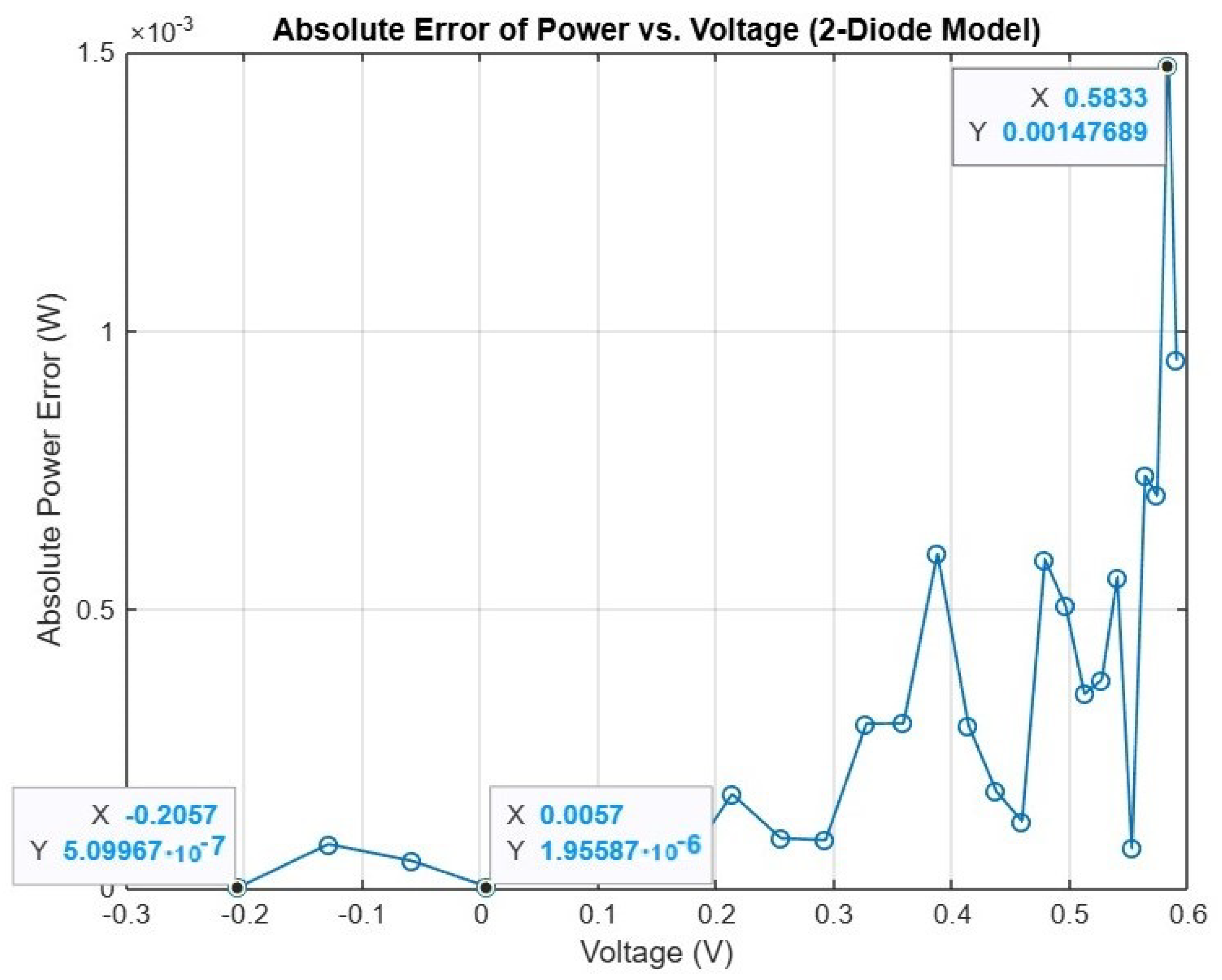

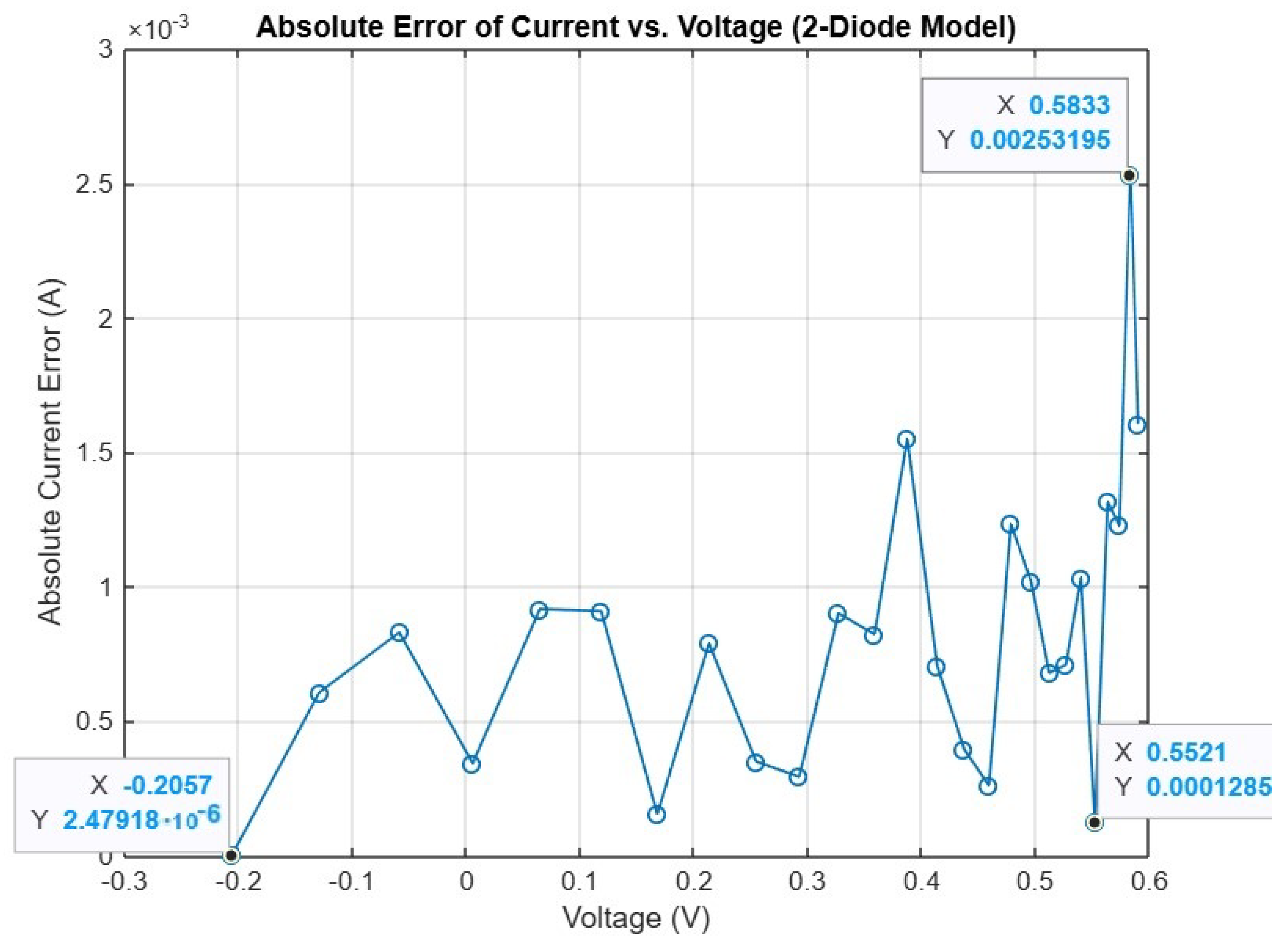

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 show the absolute error (IAE) of current and of power where the lowest absolute current error was

A, and the lowest absolute power error was

W. In addition, the small peaks near the open-circuit voltage are expected, since the cell carries almost no current in this high-voltage region, and even tiny mismatches between the measured and estimated current become more visible while remaining negligible compared with the short-circuit current and the rated maximum power.

The BKA reached its optimal solution within 996 iterations, with a CPU time of 9.7 s. The standard deviation of the RMSE was

, indicating consistent and reliable performance across multiple runs. These results are summarized in

Table 5. The optimal parameter values extracted by the BKA for the 2DM are presented in

Table 4. To validate the accuracy, the average RMSE was

, and the maximum RMSE was

, demonstrating the high precision of the BKA in estimating 2DM parameters.

BKA convergence has reached the highest level on all of these indicators listed above. The RMSE of can pull well ahead of most methods out there. This is 1.5% less than current worst RMSE of 2DM modeling using the TSA algorithm, . The minimum absolute error in current was far less than any other algorithm, , so basic estimation of electrical current of the model accuracy shows remarkable improvements. The BKA’s RMSE is , showing higher fidelity than those from GA which weighed at and TSA at . While the BKA showed a somewhat high standard deviation of , somewhat higher than TSA whose figure is , it is still within an acceptable range and quite stable over several experiments. The BKA took 9.7 s to process, less than BBO (18.3 s), so it can be considered a kind of balance of speed and accuracy. Convergence rates show that the number of iterations needed to achieve the optimal solution using the BKA algorithm (approximately 996 iterations) are close to those for WOA and TSA algorithms.

4.3. Triple-Diode Model (3DM)

The triple-diode model requires estimation of nine parameters:

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, and

. Accurate determination of these parameters is essential for high-fidelity simulations, particularly where recombination losses are significant. The BKA achieved a best RMSE of

, outperforming algorithms such as TSA, GA, WOA, and BBO, as highlighted in

Table 6 and

Table 7. This performance reflects the BKA’s effective balance between exploration and exploitation, allowing efficient navigation of the higher-dimensional parameter space.

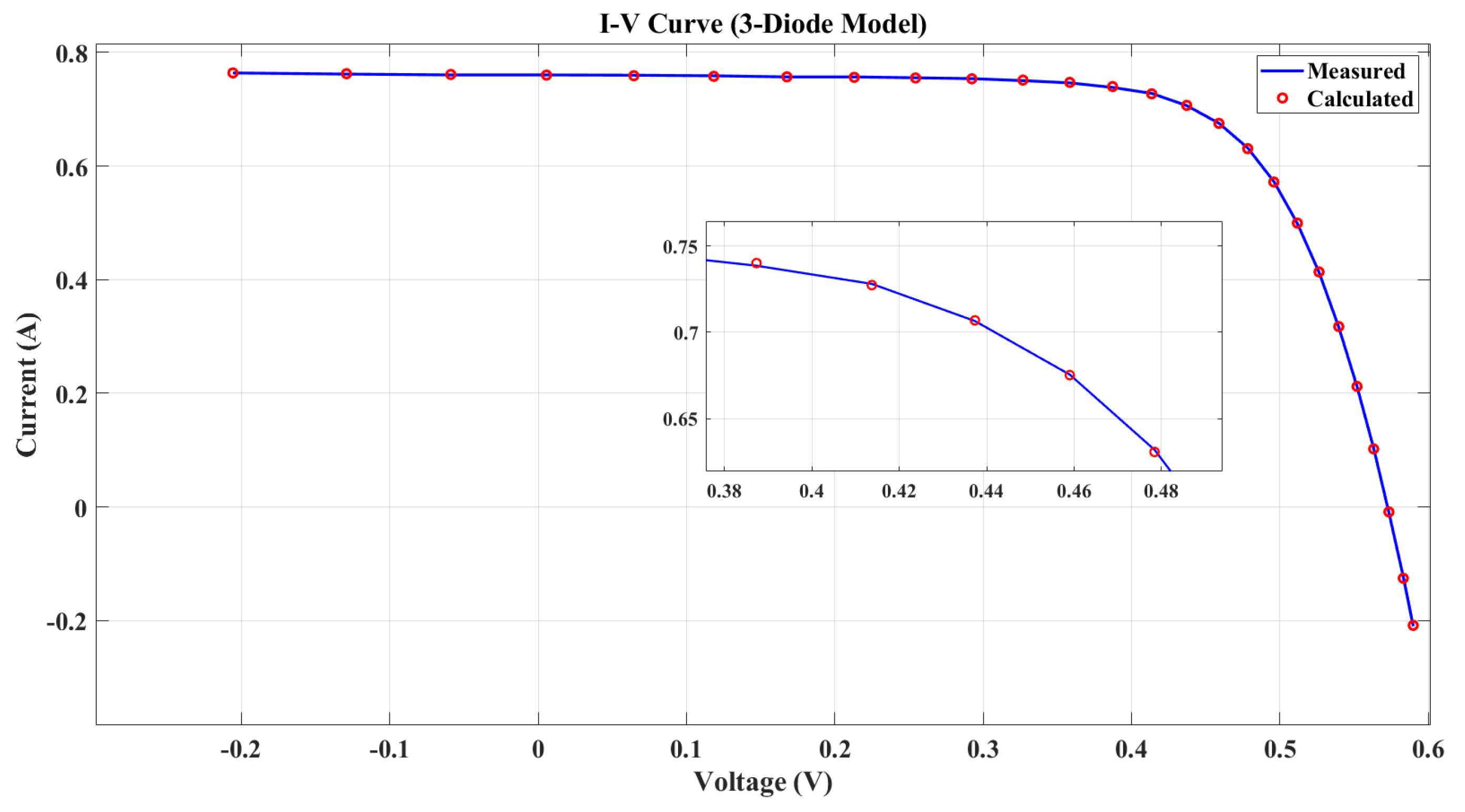

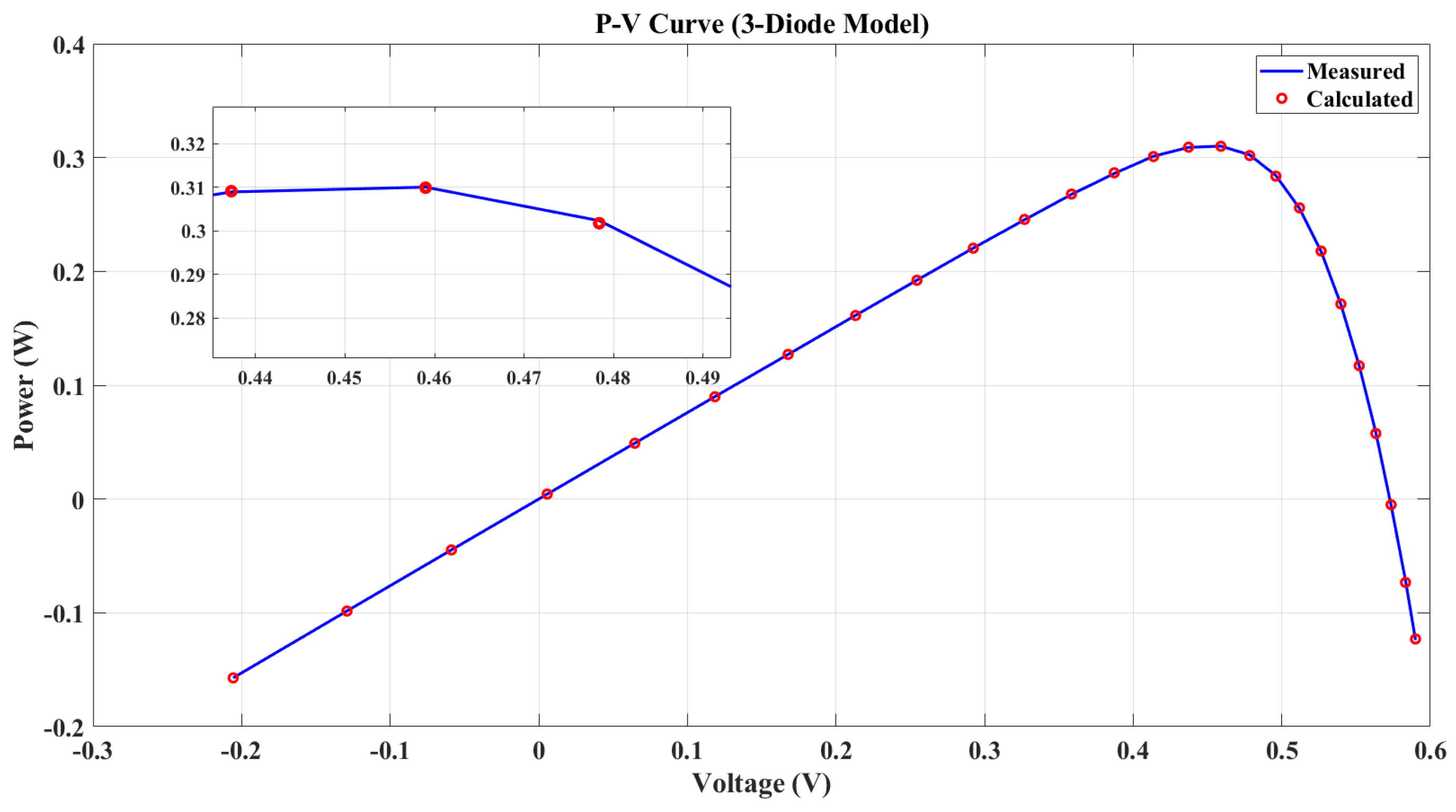

To validate the extracted parameters, simulated I-V and P-V characteristics were created and compared with experimental data from the solar cell. The I-V and P-V characteristics of the 3DM solar PV cell are illustrated in

Figure 15 and

Figure 16.

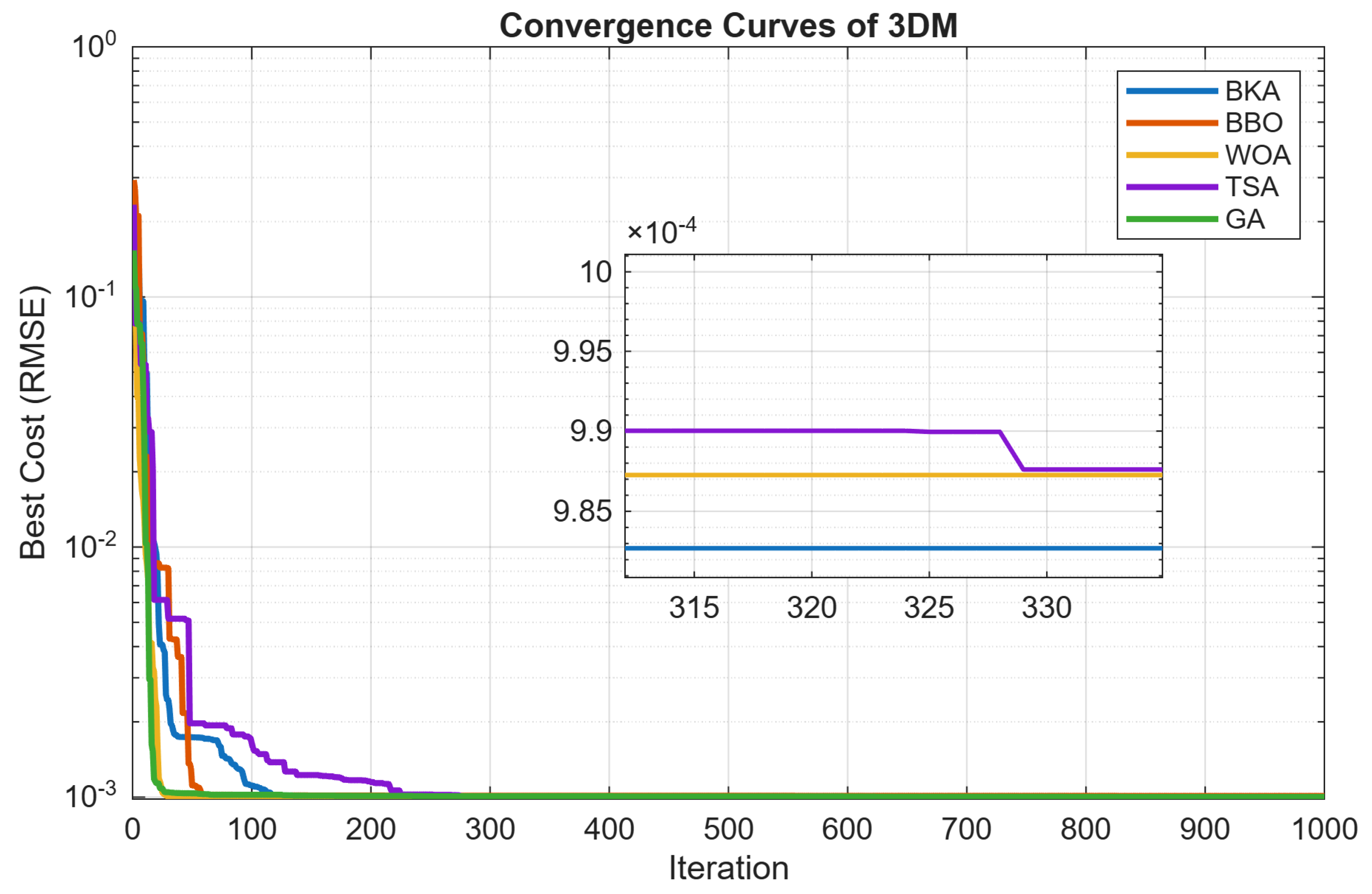

In the context of optimizing the three-dimensional model (3DM), several well-known optimization algorithms were evaluated including WOA, TSA, GA, and BBO alongside the proposed BKA algorithm. Based on multiple experimental results, the academic points of superiority of the proposed algorithm are evident.

Figure 17 shows the convergence curves for the 3DM. The BKA achieves the lowest final RMSE (

) with a low standard deviation across runs (

), indicating stable and reliable convergence. TSA and WOA reduce the RMSE at a similar rate during the early iterations, but their curves plateau at higher error levels, whereas the BKA continues to improve and ultimately converges to the best solution among the tested algorithms.

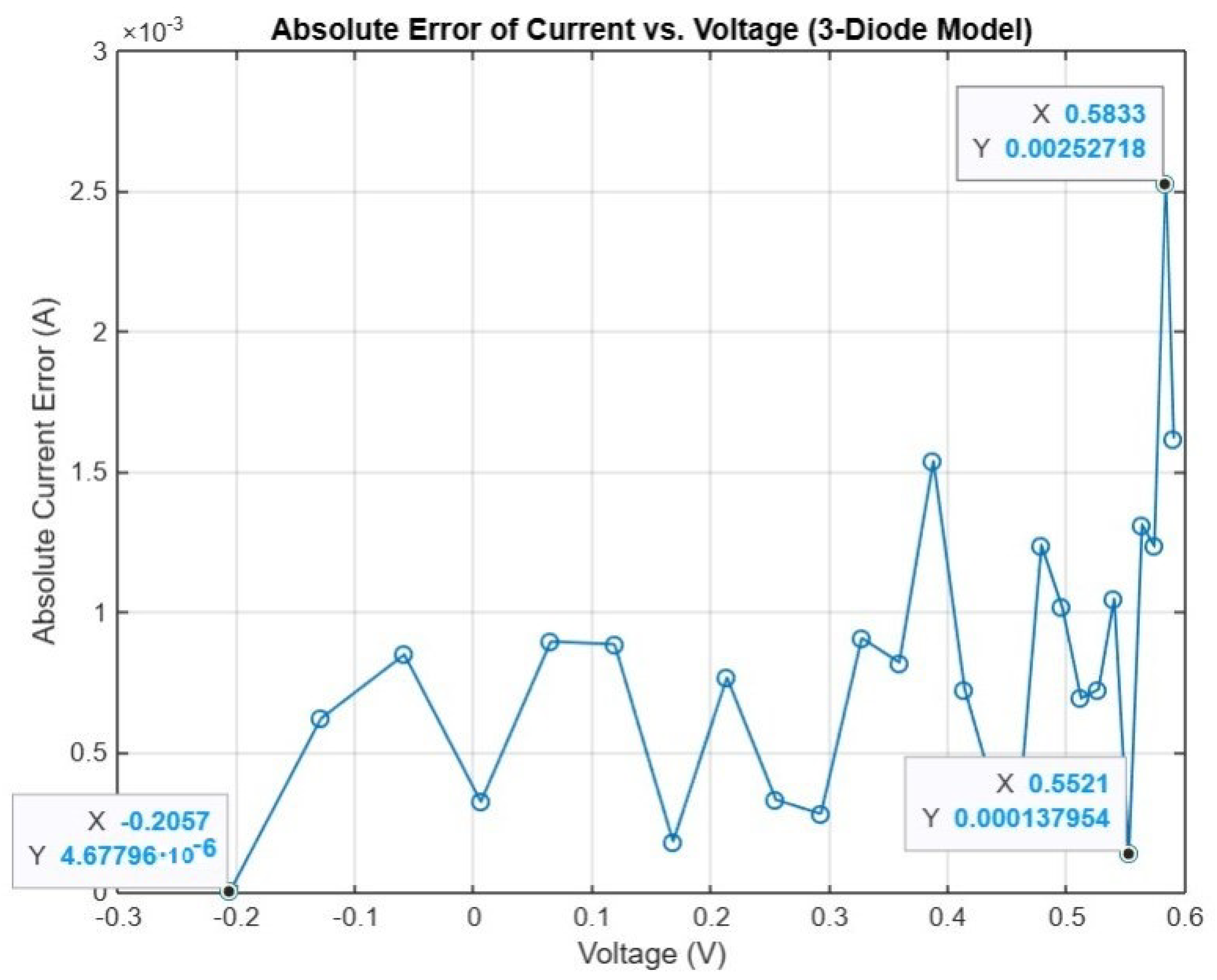

Figure 18 and

Figure 19 illustrate the absolute error of current and absolute error of power. The lowest absolute current error was

A, and the lowest absolute power error was

W. These values are around 95% less than the errors achieved by WOA and GA algorithms. In both

Figure 18 and

Figure 19, the small peaks near the open-circuit voltage are expected, as they arise in a high-voltage, low-current region where very slight mismatches between the measured and estimated current become more visible but remain negligible compared with the rated maximum power and short-circuit current.

For the 3DM, the BKA converged to its optimal solution in 999 iterations, with a CPU time of 31.0063 s. The standard deviation of the RMSE was , and the maximum RMSE was , confirming the high fidelity of the BKA-extracted parameters, indicating robust and consistent convergence to high-quality solutions. The average iterations to best solution were comparable with other algorithms, which indicated it has the nature of result the optimal solution in a reasonable time.

From an algorithmic perspective, the observed behavior aligns with each method’s inherent search mechanisms. The smooth convergence and narrow gap between the best, mean, and worst RMSE achieved by the BKA can be attributed to the combination of global migration and Cauchy-distributed local perturbations, which preserve diversity around promising regions, while the decreasing attack-intensity coefficient gradually strengthens exploitation. As the number of parameters increases from 1DM to 3DM, the WOA and TSA, which rely more heavily on leader-based position updates, reduce the RMSE rapidly in the early iterations but tend to lose diversity and plateau at higher error levels. In comparison to the BKA, the GA, BBO, and DA exhibit more oscillations and variability, suggesting greater sensitivity to population initialization and control settings, as well as a higher tendency to become trapped in local minima. Taken together, these trends show that the proposed BKA produces the most accurate parameter estimates, with very low absolute errors in current and power, high stability over multiple runs, and a favorable trade-off between computational time and accuracy, making it a strong candidate for further research and practical PV modeling applications.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, the Black-Winged Kite Algorithm (BKA) was employed to estimate the parameters of three widely used photovoltaic models—the single-diode (1DM), double-diode (2DM), and triple-diode (3DM) models—using experimental I–V data from an RTC France silicon solar cell measured at 33 °C and 1000 W/m2. All competing algorithms were tested under identical parameter bounds, population sizes, and iteration limits, and each configuration was executed over 30 independent runs to ensure a fair comparison and to assess statistical robustness.

Across all three PV models, the BKA consistently achieved the lowest or among the lowest root mean square error (RMSE) values while maintaining a manageable computational burden. In addition to exhibiting very low absolute current and power errors, the BKA attained the best RMSE and the smallest RMSE standard deviation for the 1DM, indicating both high stability and excellent accuracy. For the 2DM and 3DM, the BKA reached best-case RMSE values and very small absolute errors in current and power, with convergence behavior that remained comparable to the fastest competing metaheuristics. Taken together, these results indicate that the BKA offers a favorable balance between accuracy, robustness, and execution time for multidimensional PV parameter estimation when compared with established bio-inspired optimizers such as the WOA, GA, TSA, BBO, ALO, and DA. At the same time, several limitations of the present study should be acknowledged. First, the analysis was restricted to a single silicon cell type and to one operating condition (fixed irradiance and temperature), so the behavior of the BKA across different PV technologies, module configurations, and broader environmental conditions remains to be quantified. Second, only noise-free laboratory measurements with 26 I–V points were considered; the performance of the BKA under measurement noise, ageing effects, or partial-shading scenarios was not examined. Third, the formulation adopted here is single-objective and based solely on RMSE, without explicitly incorporating multi-objective trade-offs (for example, between accuracy, computation time, and parameter regularity) or hybridization with local search strategies.

Future research should expand the evaluation of the BKA across diverse PV technologies and realistic conditions, such as partial shading and signal noise. Integrating the BKA into hybrid schemes with gradient-based refinement and adopting multi-objective formulations could further optimize the balance between accuracy and computational speed. Additionally, incorporating non-parametric statistical validations, like Wilcoxon or Friedman tests, will provide more robust verification of algorithmic rankings. Ultimately, embedding the BKA into real-time MPPT, online monitoring, and fault-diagnosis frameworks will be vital to demonstrating its practical utility in industrial PV control applications.