Environmental and Safety Performance of European Railways: An Integrated Efficiency Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Sustainable Mobility

2.2. Transport Efficiency Measurement

2.3. Methodology Background

2.4. Undesirable Outputs

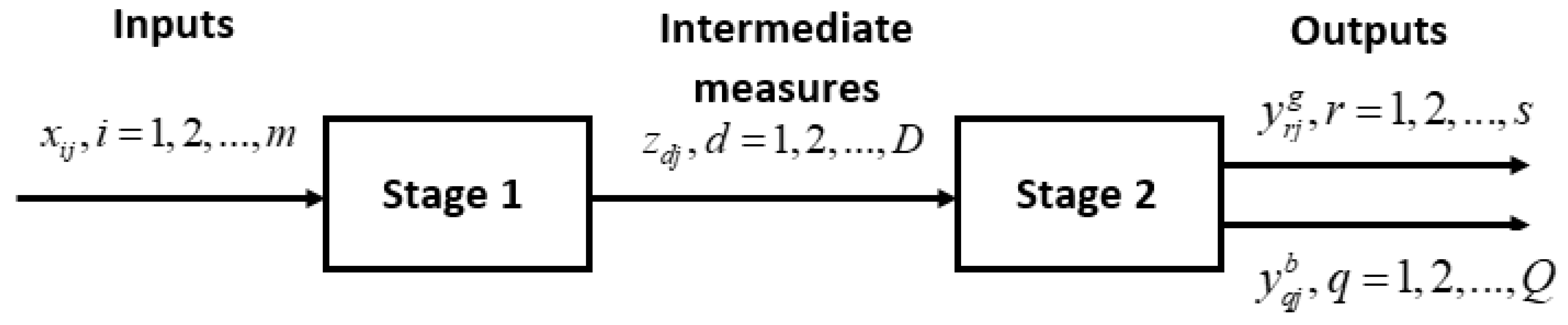

3. Methodology

3.1. Slack-Based Measure Model

3.2. Variable Intermediate Slack-Based Measure Model

3.3. Variable Intermediate Slack-Based Measure with Undesirable Outputs

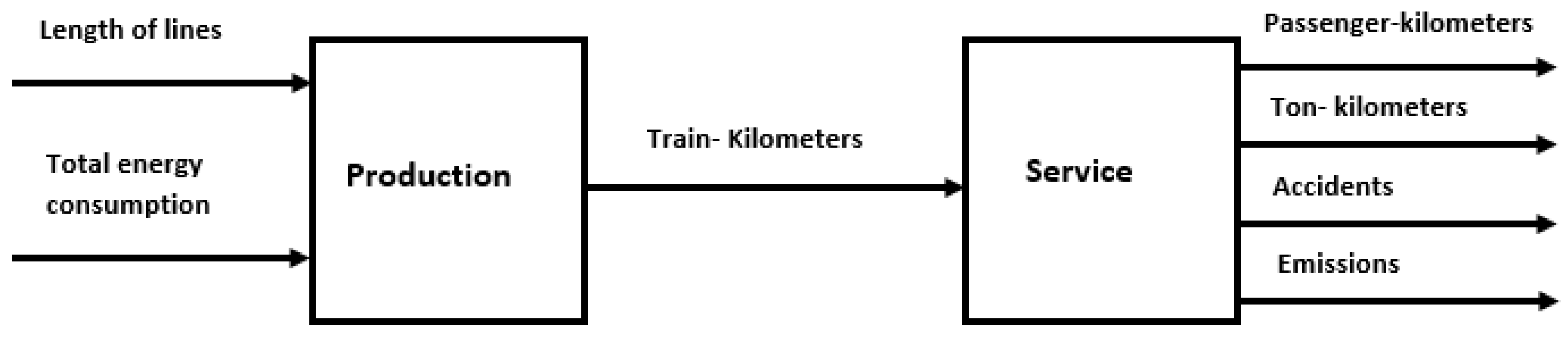

4. Data Description

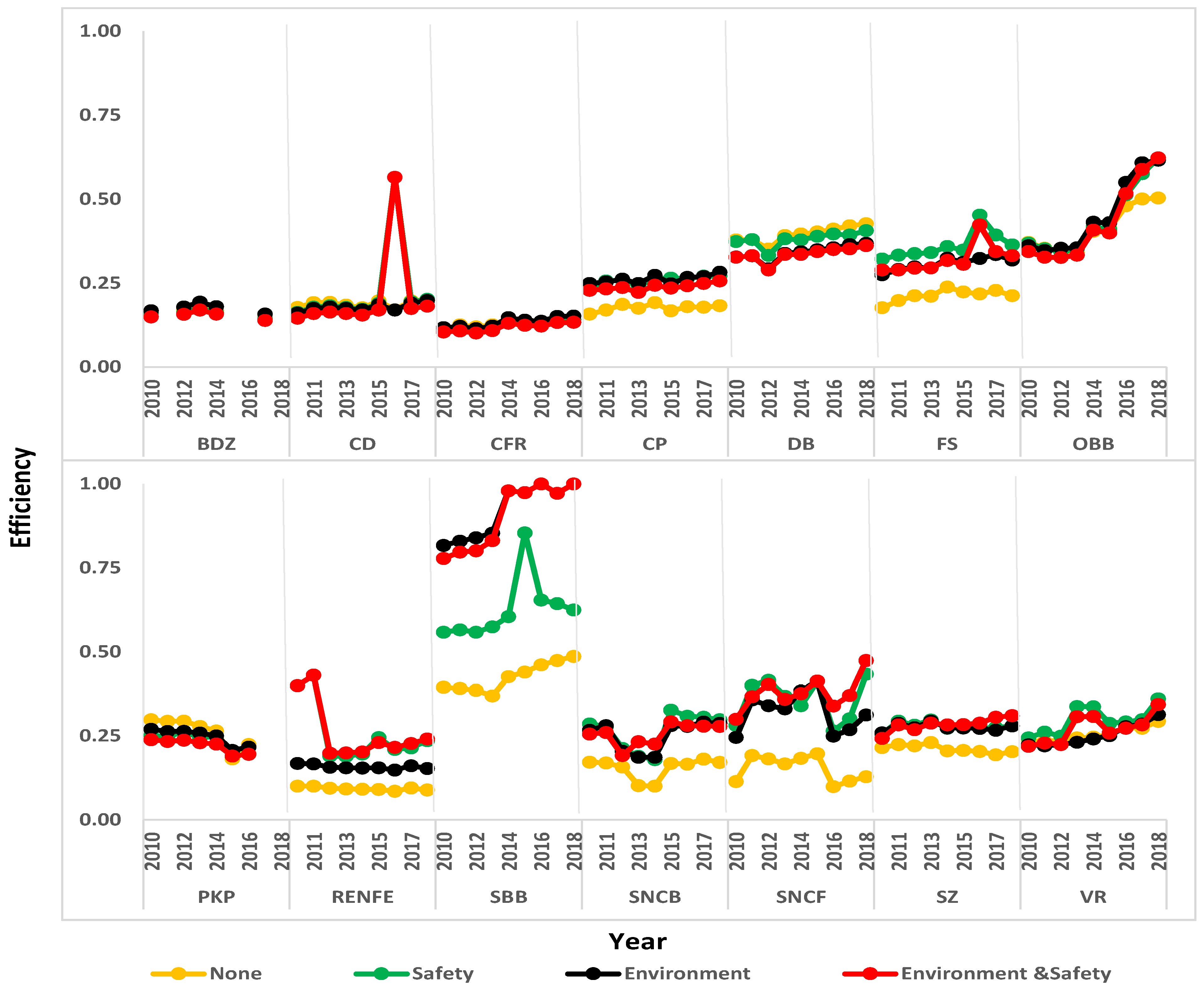

5. Efficiency Evaluation of Railway Operations

5.1. Model Comparison and Validation

5.2. Performance Analysis Across DEA Configurations

5.2.1. Comparative Summary of Operator Efficiencies

5.2.2. Temporal Dynamics of Efficiency

5.2.3. Cross-Model Ranking Analysis

5.3. Combined Environmental and Safety Performance

6. Conclusions and Implications for Policy and Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Commission. The Transport and Mobility Sector; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano, G.; Daraio, C.; Diana, M.; Gregori, M.; Matteucci, G. Efficiency, Effectiveness, and Impacts Assessment in the Rail Transport Sector: A State-of-the-Art Critical Analysis of Current Research. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2018, 26, 5–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The Journey Begins—2021 Is the European Year of Rail! European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021; pp. 2020–2021. [Google Scholar]

- Djordjevic, B.; Sadashiv, A.; Krmac, E. Research in Transportation Business & Management Analysis of Dependency and Importance of Key Indicators for Railway Sustainability Monitoring: A New Integrated Approach with DEA and Pearson Correlation. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2021, 41, 100650. [Google Scholar]

- Stefaniec, A.; Hosseini, K.; Xie, J.; Li, Y. Sustainability Assessment of Inland Transportation in China: A Triple Bottom Line-Based Network DEA Approach. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 80, 102258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, R.; Emrouznejad, A.; Shetab-Boushehri, S.N.; Hejazi, S.R. The Origins, Development and Future Directions of Data Envelopment Analysis Approach in Transportation Systems. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 69, 100672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Chen, X. Decomposition Weights and Overall Efficiency in a Two-Stage DEA Model with Shared Resources. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 136, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J. Data Envelopment Analysis Application in Sustainability: The Origins, Development and Future Directions. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 264, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuyama, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Managi, S. Modal Choice between Air and Rail: A Social Efficiency Benchmarking Analysis That Considers CO2 Emissions. Environ. Econ. Policy Stud. 2011, 13, 89–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djordjevic, B.; Krmac, E.; Mlinarić, T.J. Non-Radial DEA Model: A New Approach to Evaluation of Safety at Railway Level Crossings. Saf. Sci. 2018, 103, 234–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, G.; Kim, H. Analysis of Operational Efficiency Considering Safety Factors as an Undesirable Output for Coastal Ferry Operators in Korea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.W. Accidental Fatalities in Transport. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A Stat. Soc. 2003, 166, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, M.R. Fuel Economy and Safety: The Influences of Vehicle Class and Driver Behavior. Am. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 2013, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, Y.; Liang, L.; Salo, A.; Wu, H. Frontier Projection and Efficiency Decomposition in Two-Stage Processes with Slacks-Based Measures. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 250, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, C. A Classification of Slacks-Based Efficiency Measures in Network Data Envelopment Analysis with an Analysis of the Properties Possessed. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 270, 1109–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, W.D.; Zhu, J.; Bi, G.; Yang, F. Network DEA: Additive Efficiency Decomposition. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 207, 1122–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. Dealing with Undesirable Outputs in DEA: A Slacks-Based Measure (SBM) Approach. GRIPS Discuss. Pap. 2004, 1, 44–45. [Google Scholar]

- UIC; CER. Moving Rowards Sustaunable Mobility; CER: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.; Chen, B.; Xie, L.; Pan, H. Estimating Energy Consumption of Transport Modes in China Using DEA. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4225–4239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. A Community Strategy for ‘Sustainable Mobility’; EU Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, E.; Gilpin, G.; Banister, D. Sustainable Mobility at Thirty. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Ke, Y.; Zuo, J.; Xiong, W.; Wu, P. Evaluation of Sustainable Transport Research in 2000–2019. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karjalainen, L.E.; Juhola, S. Urban Transportation Sustainability Assessments: A Systematic Review of Literature. Transp. Rev. 2021, 41, 659–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloui, A.; Hamani, N.; Derrouiche, R.; Delahoche, L. Systematic Literature Review on Collaborative Sustainable Transportation: Overview, Analysis and Perspectives. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2021, 9, 100291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, L.; Proff, H. Sustainable Urban Transportation Criteria and Measurement—A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, S.; Contreras, K.D.; Kappiantari, M.; Tuan, N.A.; Guillen, M.D.; Gunthawong, G.; Zuidgeest, M.; Liefferink, D.; van Maarseveen, M. Low-Carbon Transport Policy in Four ASEAN Countries: Developments in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starr McMullen, B.; Noh, D.W. Accounting for Emissions in the Measurement of Transit Agency Efficiency: A Directional Distance Function Approach. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2007, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oum, T.H.; Pathomsiri, S.; Yoshida, Y. Limitations of DEA-Based Approach and Alternative Methods in the Measurement and Comparison of Social Efficiency across Firms in Different Transport Modes: An Empirical Study in Japan. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2013, 57, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.T.; Park, H.S.; Jeong, J.B.; Lee, J.W. Evaluating Economic and Environmental Efficiency of Global Airlines: A SBM-DEA Approach. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2014, 27, 46–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noroozzadeh, A.; Sadjadi, S.J. A New Approach to Evaluate Railways Efficiency Considering Safety Measures. Decis. Sci. Lett. 2013, 2, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhuang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, H.; Yang, H. Railway Safety Risk Assessment and Control Optimization Method Based on FTA-FPN: A Case Study of Chinese High-Speed Railway Station. J. Adv. Transp. 2020, 2020, 3158468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.-M.; Fan, C.-K. Measuring the Cost Effectiveness of Multimode Bus Transit in the Presence of Accident Risks. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2006, 29, 383–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, H.; Pitfield, D.E. ELASTIC—A Methodological Framework for Identifying and Selecting Sustainable Transport Indicators. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2010, 15, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, P.; de Barros, A.G.; Kattan, L.; Wirasinghe, S.C. Analyzing the Sustainability Performance of Public Transit. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2016, 44, 177–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sdoukopoulos, A.; Pitsiava-Latinopoulou, M.; Basbas, S.; Papaioannou, P. Measuring Progress towards Transport Sustainability through Indicators: Analysis and Metrics of the Main Indicator Initiatives. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 67, 316–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITF. Transport Infrastructure Investment; ITF: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.H.; Jung, K. Measuring Efficiency and Effectiveness of Highway Management in Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daraio, C.; Diana, M.; Di Costa, F.; Leporelli, C.; Matteucci, G.; Nastasi, A. Efficiency and Effectiveness in the Urban Public Transport Sector: A Critical Review with Directions for Future Research. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 248, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aigner, D.; Lovell, C.A.K.; Schmidt, P. Formulation and Estimation of Stochastic Frontier Production Function Models. J. Econom. 1977, 6, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, M.J. The Measurement of Productive Efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. A 1957, 120, 253–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Á.; Markellos, R.N. Evaluating Public Transport Efficiency with Neural Network Models. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 1997, 5, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the Efficiency of Decision Making Units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiford, L.M.; Thrall, R.M. Recent Developments in DEA: The Mathematical Programming Approach to Frontier Analysis. J. Econom. 1990, 46, 7–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, W.W.; Seiford, L.; Tone, K. Introduction to Data Envelopment Analysis and Its Uses; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jordá, P.; Cascajo, R.; Monzón, A. Analysis of the Technical Efficiency of Urban Bus Services in Spain Based on SBM Models. ISRN Civ. Eng. 2012, 2012, 984758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, L.; Murphy, D.J.; Pearson, J.N. Purchasing Performance Evaluation: With Data Envelopment Analysis. Eur. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2002, 8, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.C.; Goddard, M. Performance Management and Operational Research: A Marriage Made in Heaven? J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2002, 53, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lai, F.; Wang, Y.M.; Huang, Y.; Wu, F.M. A Two-Stage Network Data Envelopment Analysis Approach for Measuring and Decomposing Environmental Efficiency. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 119, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, H.; Behdani, B.; Wiegmans, B.; Zuidwijk, R. Assessing the Technical Efficiency of Intermodal Freight Transport Chains Using a Modified Network DEA Approach. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2019, 126, 66–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, D.; Wanke, P. Brazil’s Rail Freight Transport: Efficiency Analysis Using Two-Stage DEA and Cluster-Driven Public Policies. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2017, 59, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiford, L.M.; Zhu, J. Modeling Undesirable Factors in Efficiency Evaluation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2002, 142, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, S.A.; Førsund, F.R.; Jansen, E.S. Malmquist Indices of Productivity Growth during the Deregulation of Norwegian Banking, 1980–1989. Scand. J. Econ. 1992, 94, S211–S228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovell, C.; Pastor, J.; Turner, J.A. Measuring Macroeconomic Performance in the OECD: A Comparison of European and Non-European Countries. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1995, 87, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyteca, D. Linear Programming Models for the Measurement of Environmental Performance of Firms—Concepts and Empirical Results. J. Product. Anal. 1997, 8, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K. A Slacks-Based Measure of Efficiency in Data Envelopment Analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2001, 130, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Färe, R.; Grosskopf, S. Directional Distance Functions and Slacks-Based Measures of Efficiency: Some Clarifications. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 206, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picazo-Tadeo, A.J.; Reig-Martínez, E.; Hernández-Sancho, F. Directional Distance Functions and Environmental Regulation. Resour. Energy Econ. 2005, 27, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.-C.; Khan, H.A.; Feng, C.-M.; Wu, C.-C. Efficiency Evaluation of Bus Transit Firms with and without Consideration of Environmental Air-Pollution Emissions. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2017, 50, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.S.; Lim, S.H.; Egilmez, G.; Szmerekovsky, J. Environmental Efficiency Assessment of U.S. Transport Sector: A Slack-Based Data Envelopment Analysis Approach. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 61, 152–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.D. Assessing Road Transport Sustainability by Combining Environmental Impacts and Safety Concerns. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 77, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, S.; Gutiérrez, E. A Slacks-Based Network DEA Efficiency Analysis of European Airlines. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2014, 37, 623–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tone, K.; Tsutsui, M. Network DEA: A Slacks-Based Measure Approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2009, 197, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cook, W.D.; Kao, C.; Zhu, J. Network DEA Pitfalls: Divisional Efficiency and Frontier Projection under General Network Structures. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2013, 226, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavassoli, M.; Faramarzi, G.R.; Saen, R.F. A Joint Measurement of Efficiency and Effectiveness Using Network Data Envelopment Analysis Approach in the Presence of Shared Input. Opsearch 2015, 52, 490–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.M. Assessing the Technical Efficiency, Service Effectiveness, and Technical Effectiveness of the World’s Railways through NDEA Analysis. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2008, 42, 1283–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.M.; Lin, E.T.J. Efficiency and Effectiveness in Railway Performance Using a Multi-Activity Network DEA Model. Omega 2008, 36, 1005–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Hu, H. Sustainability Evaluation of Railways in China Using a Two-Stage Network DEA Model with Undesirable Outputs and Shared Resources. Sustainability 2017, 9, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Programming with Linear Fractional Functionals. Nav. Res. Logist. Q. 1962, 9, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benga, A.; Delgado Rodríguez, M.J.; de Lucas Santos, S.; Zeneli, G. Efficiency Analysis of European Railway Companies and the Effect of Demand Reduction. J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 2025, 34, 100516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benga, A.; Zeneli (Foto), G.; Delgado-Rodríguez, M.J.; de Lucas Santos, S. Company Efforts and Environmental Efficiency: Evidence from European Railways Considering Market-Based Emissions; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, V.; Aparicio, J.; Zhu, J. The Curse of Dimensionality of Decision-Making Units: A Simple Approach to Increase the Discriminatory Power of Data Envelopment Analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 279, 929–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input/Output | Code | Description | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Length of lines | Total length of lines—end of year (km) | |

| Total energy consumption | The total energy used for traction, services, and facilities (GWh). | ||

| Intermediate Output | Train-Kilometers | All train movements of the operator (Thousand train-kilometers) | |

| Desirable Output | Passenger-Kilometers | Passenger traffic of the railway operator (domestic + international) (Million passenger kilometer) | |

| Ton-Kilometers | Freight traffic of the railway operator (domestic + international) (Million ton-kilometer) | ||

| Undesirable Output | Accidents | Number of accidents—total (Number) | |

| Location-based emissions | Total CO2eq location-based emissions (tCO2eq). | ||

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of DMUs (count) | 14 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 12 |

| Length of lines (km) | 11,439.7 (10,278.5) | 11,978.5 (10,497.9) | 11,341.1 (10,208.2) | 11,419.8 (10,271.4) | 11,421.4 (10,275.0) | 11,868.9 (10,262.1) | 11,898.3 (10,315.2) | 10,790.7 (10,345.5) | 11,270.3 (10,436.6) |

| Total energy consumption (GWh) | 3257.4 (3681.9) | 3380.2 (3691.4) | 3035.7 (3537.7) | 3045.4 (3533.6) | 2946.9 (3368.4) | 3088.5 (3283.2) | 3038.5 (3151.1) | 2835 (3195.1) | 2999.6 (3150.1) |

| Train-Kilometers (Thousand train-kilometers) | 196,663.4 (230,881.2) | 206,733.3 (230,616.5) | 188,214.5 (221,582.4) | 185,710.3 (27,780.8) | 183,374.8 (217,080.5) | 188,859 (215,482.9) | 194,486.3 (219,549.9) | 187,050.7 (217,681.4) | 199,791.3 (217,767.3) |

| Passenger-Kilometers (Million passenger kilometer) | 21,746.2 (27,668.3) | 23,032.4 (28,138.3) | 21,131.6 (28,066.4) | 21,330.7 (26,694.5) | 21,395.7 (27,543.6) | 22,752.5 (28,389.4) | 23,591.6 (29,158) | 23,888.8 (31,014.1) | 25,609.7 (30,719.2) |

| Ton-Kilometers (Million ton-kilometer) | 19,120.6 (26,713.6) | 21,892.4 (29,329.7) | 17,273.2 (20,394.3) | 18,880.9 (27,780.8) | 19,292 (26,308.5) | 20,371.6 (25,604.1) | 18,837.9 (24,446.1) | 17,534.5 (24,300.6) | 17,393.7 (23,627.7) |

| Accidents (count) | 146.1 (209.4) | 149.7 (222.3) | 166.5 (227.9) | 179.4 (236.3) | 155 (193.4) | 99.6 (100.7) | 85 (92.6) | 115 (117.7) | 94.8 (103.1) |

| Emissions (tCO2eq) | 1146.3 (1557.5) | 1243.1 (1674.4) | 1107.9 (1595.1) | 1043.5 (1551.1) | 961.8 (1456.9) | 997.2 (1375.6) | 966.5 (1316.3) | 819.3 (1204.4) | 819.5 (1182.3) |

| Length of Lines | Train-km | Location-Based Emissions | Accidents | Passenger-km | Ton-km | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of Lines | 1 | 0.888 ** | 0.811 ** | 0.394 ** | 0.902 ** | 0.769 ** |

| Total energy consumption | 0.936 ** | 0.980 ** | 0.844 ** | 0.261 ** | 0.961 ** | 0.856 ** |

| Train-km | 0.888 ** | 1 | 0.882 ** | 0.257 ** | 0.920 ** | 0.905 ** |

| Score | Normal SBM | Variable SBM |

|---|---|---|

| <0.500 | 79 | 107 |

| 0.500–0.599 | 16 | 3 |

| 0.600–0.699 | 4 | 1 |

| 0.700–0.799 | 4 | 2 |

| 0.800–0.899 | 3 | 2 |

| 0.900–0.999 | 1 | 3 |

| 1 | 13 | 2 |

| Maximum | 1 | 1 |

| Minimum | 0.150 | 0.101 |

| Mean | 0.475 | 0.319 |

| Std. Deviation | 0.240 | 0.194 |

| Company | N | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Last | First | Last | First | Last | D | First | Last | |||||

| OBB | 9 | 0.344 | 0.622 | 81.02% | 0.361 | 0.616 | 70.5% | 0.369 | 0.622 | 68.7% | 0.371 | 0.503 | 35.7% |

| SNCB | 9 | 0.255 | 0.279 | 9.13% | 0.267 | 0.287 | 7.6% | 0.286 | 0.298 | 4.2% | 0.172 | 0.171 | −0.3% |

| BDZ | 5 | 0.148 | 0.138 | −6.81% | 0.167 | 0.157 | −6.0% | 0.160 | 0.143 | −10.5% | 0.162 | 0.153 | −5.6% |

| SBB | 9 | 0.778 | 1.000 | 28.62% | 0.816 | 1.000 | 22.5% | 0.558 | 0.624 | 11.8% | 0.395 | 0.486 | 23.1% |

| CD | 9 | 0.145 | 0.181 | 24.40% | 0.160 | 0.197 | 23.1% | 0.162 | 0.201 | 24.4% | 0.177 | 0.201 | 13.9% |

| DB | 9 | 0.326 | 0.361 | 10.55% | 0.328 | 0.368 | 12.3% | 0.373 | 0.406 | 8.8% | 0.378 | 0.426 | 12.7% |

| RENFE | 9 | 0.400 | 0.241 | −39.66% | 0.168 | 0.153 | −8.9% | 0.399 | 0.236 | −40.9% | 0.100 | 0.089 | −11.4% |

| VR | 9 | 0.219 | 0.344 | 57.06% | 0.223 | 0.314 | 40.3% | 0.244 | 0.361 | 47.6% | 0.237 | 0.294 | 24.0% |

| SNCF | 9 | 0.300 | 0.474 | 58.10% | 0.246 | 0.313 | 27.1% | 0.281 | 0.434 | 54.2% | 0.114 | 0.128 | 12.4% |

| FS | 9 | 0.288 | 0.331 | 14.73% | 0.274 | 0.318 | 16.0% | 0.321 | 0.363 | 13.0% | 0.176 | 0.212 | 19.9% |

| PKP | 7 | 0.239 | 0.196 | −18.07% | 0.270 | 0.216 | −19.8% | 0.252 | 0.217 | −13.8% | 0.298 | 0.225 | −24.7% |

| CP | 9 | 0.228 | 0.256 | 12.27% | 0.249 | 0.282 | 13.4% | 0.237 | 0.271 | 14.2% | 0.157 | 0.182 | 15.8% |

| CFR | 9 | 0.104 | 0.133 | 27.59% | 0.117 | 0.151 | 28.8% | 0.112 | 0.140 | 24.9% | 0.112 | 0.134 | 19.7% |

| SZ | 9 | 0.243 | 0.310 | 27.83% | 0.259 | 0.280 | 8.0% | 0.255 | 0.280 | 9.5% | 0.215 | 0.203 | −5.5% |

| DMU | vs. | vs. | vs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD | 0.037 | 4.377 | 4.956 |

| CFR | 0.423 | 0.107 | 1.275 |

| CP | 1.404 | 1.148 | 2.737 |

| DB | 0.299 | 0.431 | 0.736 |

| FS | 0.440 | 2.332 | 3.154 |

| OBB | 0.150 | 0.255 | 0.559 |

| RENFE | 0.234 | 1.641 | 1.871 |

| SBB | 2.524 | 0.121 | 1.380 |

| SNCB | 1.441 | 1.538 | 2.677 |

| SNCF | 1.755 | 2.870 | 3.336 |

| SZ | 2.973 | 3.116 | 4.829 |

| VR | 0.391 | 2.215 | 2.180 |

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kendall’s Tau | 0.648 ** | 0.718 ** | 0.912 ** | 0.714 ** | 0.868 ** | 0.923 ** | 0.564 ** | 0.744 ** | 0.788 ** | |

| 0.890 ** | 0.923 ** | 0.978 ** | 0.890 ** | 0.890 ** | 0.974 ** | 0.846 ** | 0.821 ** | 0.939 ** | ||

| vs. | 0.231 | 0.308 | 0.495 * | 0.451 * | 0.582 ** | 0.564 ** | 0.359 | 0.538 * | 0.576 ** | |

| Spearman’s Rho | 0.723 ** | 0.692 ** | 0.969 ** | 0.881 ** | 0.952 ** | 0.978 ** | 0.665 * | 0.857 ** | 0.923 ** | |

| 0.974 ** | 0.978 ** | 0.996 ** | 0.974 ** | 0.969 ** | 0.995 ** | 0.945 ** | 0.929 ** | 0.986 ** | ||

| vs. | 0.314 | 0.363 | 0.679 ** | 0.591 * | 0.749 ** | 0.742 ** | 0.484 | 0.626 * | 0.664 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Benga, A.; Rodríguez, M.J.D.; de Lucas Santos, S.; El Mir, G. Environmental and Safety Performance of European Railways: An Integrated Efficiency Assessment. Algorithms 2026, 19, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010010

Benga A, Rodríguez MJD, de Lucas Santos S, El Mir G. Environmental and Safety Performance of European Railways: An Integrated Efficiency Assessment. Algorithms. 2026; 19(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleBenga, Arsen, María Jesús Delgado Rodríguez, Sonia de Lucas Santos, and Ghina El Mir. 2026. "Environmental and Safety Performance of European Railways: An Integrated Efficiency Assessment" Algorithms 19, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010010

APA StyleBenga, A., Rodríguez, M. J. D., de Lucas Santos, S., & El Mir, G. (2026). Environmental and Safety Performance of European Railways: An Integrated Efficiency Assessment. Algorithms, 19(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/a19010010