Delayed Star Subgradient Methods for Constrained Nondifferentiable Quasi-Convex Optimization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

- (i)

- is a nonempty set;

- (ii)

- is a closed, convex cone.

3. Algorithms and Convergence Results

3.1. Delayed Star Subgradient Method I

| Algorithm 1 Delayed Star Subgradient Method I (DSSM-I) |

| Initialization: Given a stepsize the delays , and initial points . Iterative Step: For a current point , we compute Update . |

- (i)

- Since the function f is quasi-convex, we note that DSSM-I is well defined. In fact, using Fact 1, we have for any , . Hence, we are able to select any point and subsequently set . Moreover, since it is clear that for all .

- (ii)

- If for all , DSSM-I coincides with the star subgradient method (SSM), which was proposed by Kiwiel [1].

- (i)

- Constant delay [18], that is, for all .

- (ii)

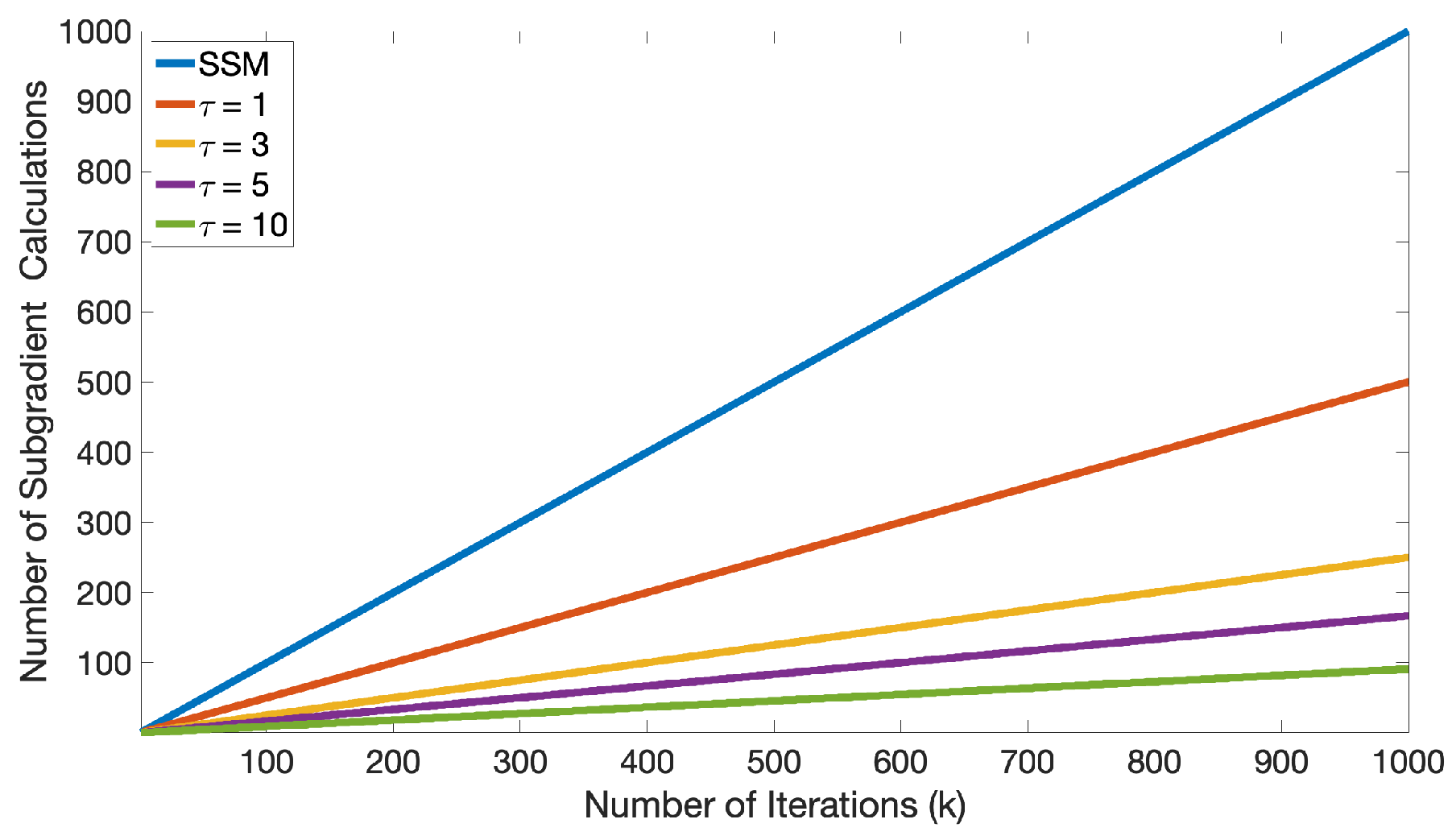

- Cyclic delay [19,20,24,26] and references therein. The typical form of this type is for all . In this case, the delays () are chosen with deterministic order from the set . This means that we will use stale information over a consistent period of length and update the new star subgradient at every iteration.

- (iii)

- Random delay [25], that is, the delays () are randomly chosen in the set .

- (i)

- For any there exists such thatwhere ;

- (ii)

- , and

3.2. Delayed Star Subgradient Method II

| Algorithm 2 Delayed Star Subgradient Method II (DSSM-II) |

| Initialization: Given a stepsize the delays , and initial points . Iterative Step: For a current point , if we set Update: . |

- (i)

- If the delays for all , DSSM-II is relating to the method proposed by Hu et al. [9] (Algorithm 1) with the special setting of .

- (ii)

- Note that DSSM-II involves evaluating the function value at the current iterate and deciding to update the next iteration . If the function value equals the optimal value , then no additional calculations are performed, and DSSM-II terminates so that an optimal solution is obtained at the point .

- (i)

- for all

- (ii)

- is nonincreasing with and ,

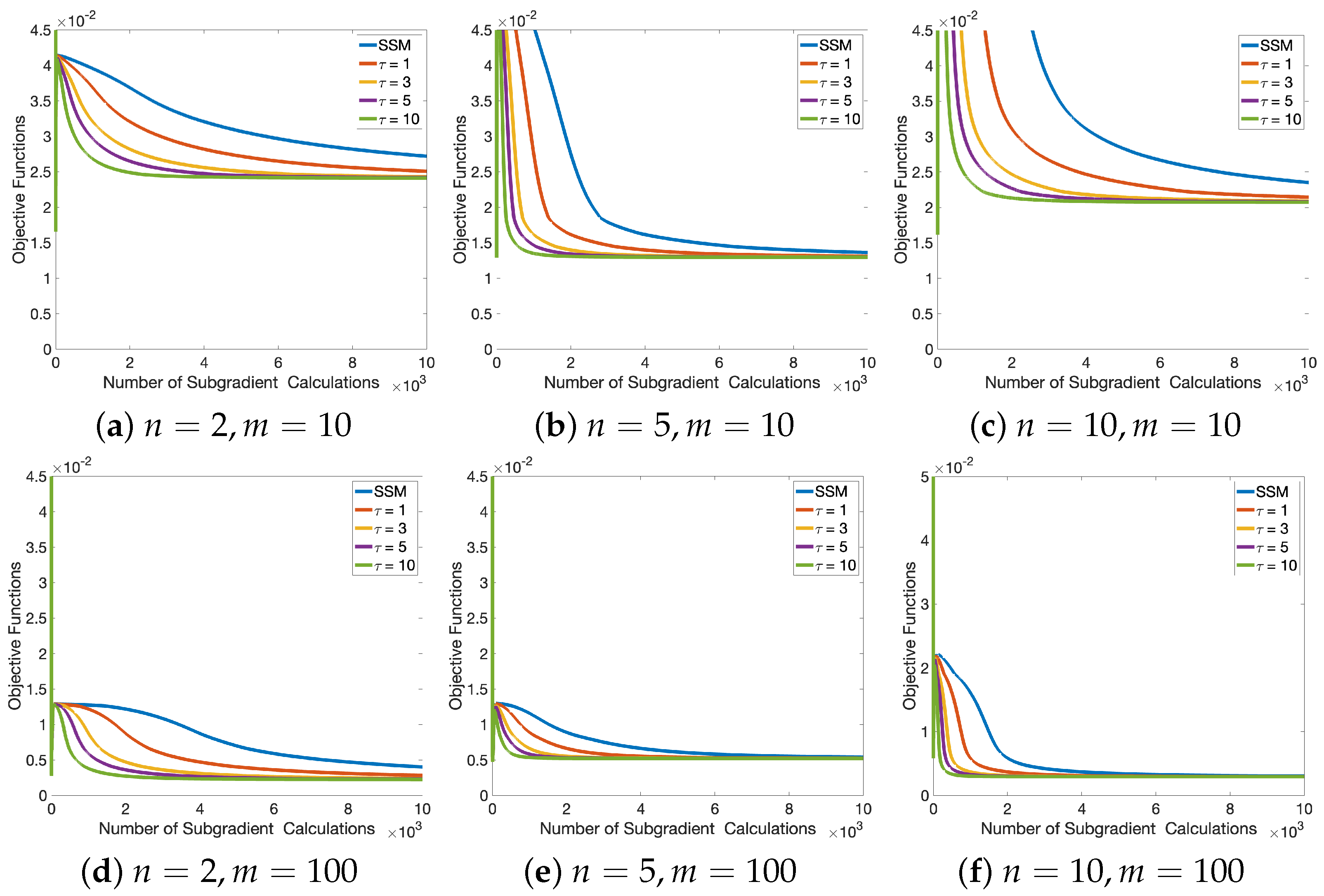

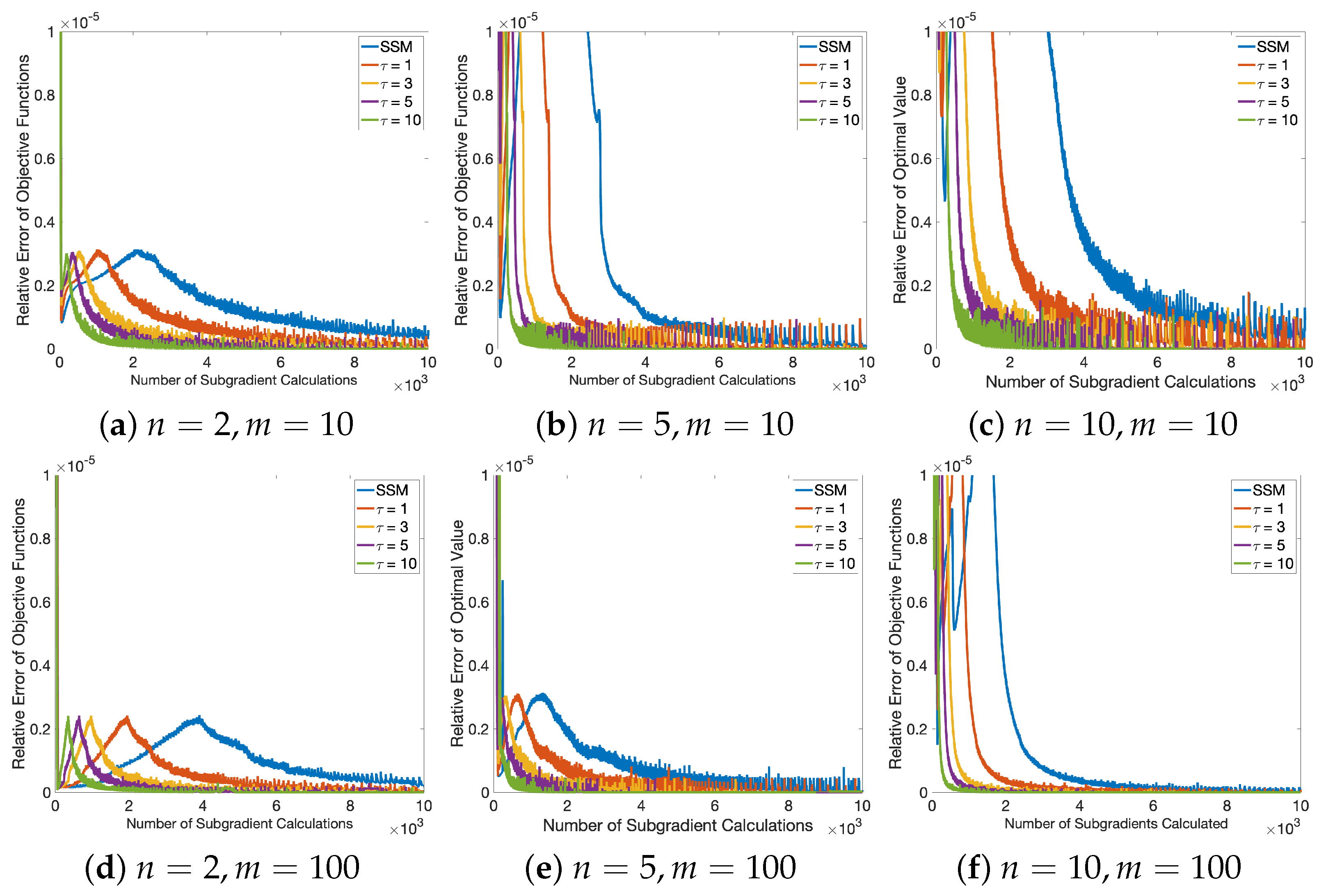

4. Numerical Experiments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kiwiel, K.C. Convergence and efficiency of subgradient methods for quasiconvex minimization. Math. Program. 2001, 90, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cambini, A.; Martein, L. Generalized Convexity and Optimization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, S.P.; Frey, S.C. Fractional programming with homogeneous functions. Oper. Res. 1974, 22, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu-Minasian, I.M. Fractional Programming; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schaible, S.; Shi, J. Fractional programming: The sum-of-ratios case. Optim. Methods Softw. 2003, 18, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, X.; Sim, C.-K. Inexact subgradient methods for quasi-convex optimization problems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 240, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yu, C.K.W.; Li, C. Stochastic subgradient method for quasi-convex optimization problems. J. Nonlinear Convex Anal. 2016, 17, 711–724. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Yu, C.K.W.; Li, C.; Yang, X. Conditional subgradient methods for constrained quasi-convex optimization problems. J. Nonlinear Convex Anal. 2016, 17, 2143–2158. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Yu, C.K.W.; Yang, X. Incremental quasi-subgradient methods for minimizing the sum of quasi-convex functions. J. Glob. Optim. 2019, 75, 1003–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konnov, I.V. On convergence properties of a subgradient method. Optim. Methods Softw. 2003, 18, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konnov, I.V. On properties of supporting and quasi-supporting vectors. J. Math. Sci. 1994, 71, 2760–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hishinuma, K.; Iiduka, H. Fixed point quasiconvex subgradient method. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 282, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choque, J.; Lara, F.; Marcavillaca, R.T. A subgradient projection method for quasiconvex minimization. Positivity 2024, 28, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Köbis, M.A.; Yao, Y. A projected subgradient method for nondifferentiable quasiconvex multiobjective optimization problems. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2021, 190, 82–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermol’ev, Y.M. Methods of solution of nonlinear extremal problems. Cybern 1966, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penot, J.-P. Are generalized derivatives useful for generalized convex functions? In Generalized Convexity, Generalized Monotonicity: Recent Results; Crouzeix, J.-P., Martinez-Legaz, J.-E., Volle, M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1998; pp. 3–59. [Google Scholar]

- Penot, J.-P.; Zălinescu, C. Elements of quasiconvex subdifferential calculus. J. Convex Anal. 2000, 7, 243–269. [Google Scholar]

- Arjevani, Y.; Shamir, O.; Srebro, N. A tight convergence analysis for stochastic gradient descent with delayed updates. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Algorithmic Learning Theory, San Diego, CA, USA, 8–11 February 2020; Kontorovich, A., Neu, G., Eds.; Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; Volume 117, pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Stich, S.U.; Karimireddy, S.P. The error-feedback framework: Better rates for sgd with delayed gradients and compressed updates. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2020, 21, 9613–9648. [Google Scholar]

- Gürbüzbalaban, M.; Ozdaglar, A.; Parrilo, P.A. On the convergence rate of incremental aggregated gradient algorithms. SIAM J. Optim. 2017, 27, 1035–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, P.; Yun, S. Incrementally updated gradient methods for constrained and regularized optimization. J. Optim. Theory Appl. 2014, 160, 832–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanli, N.D.; Gürbüzbalaban, M.; Ozdaglar, A. Global convergence rate of proximal incremental aggregated gradient methods. SIAM J. Optim. 2008, 28, 1282–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butnariu, D.; Censor, Y.; Reich, S. Distributed asynchronous incremental subgradient methods. In Inherently Parallel Algorithms in Feasibility and Optimization and Their Applications; Brezinski, C., Wuytack, L., Reich, S., Eds.; Elsevier Science B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; Volume 8, p. 381. [Google Scholar]

- Namsak, S.; Petrot, N.; Nimana, N. A distributed proximal gradient method with time-varying delays for solving additive convex optimizations. Results Appl. Math. 2023, 18, 100370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Shen, L.; Li, S.; Sun, T.; Li, D.; Tao, D. Towards understanding the generalizability of delayed stochastic gradient descent. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.09430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunrat, T.; Namsak, S.; Nimana, N. An asynchronous subgradient-proximal method for solving additive convex optimization problems. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2023, 69, 3911–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegielski, A. Iterative Methods for Fixed Point Problems in Hilbert Spaces; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Bauschke, H.H.; Combettes, P.L. Convex Analysis and Monotone Operator Theory in Hilbert Spaces, 2nd ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kiwiel, K.C. Convergence of Approximate and Incremental Subgradient Methods for Convex Optimization. SIAM J. Optim. 2004, 14, 807–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pankoon, O.; Nimana, N. Delayed Star Subgradient Methods for Constrained Nondifferentiable Quasi-Convex Optimization. Algorithms 2025, 18, 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18080469

Pankoon O, Nimana N. Delayed Star Subgradient Methods for Constrained Nondifferentiable Quasi-Convex Optimization. Algorithms. 2025; 18(8):469. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18080469

Chicago/Turabian StylePankoon, Ontima, and Nimit Nimana. 2025. "Delayed Star Subgradient Methods for Constrained Nondifferentiable Quasi-Convex Optimization" Algorithms 18, no. 8: 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18080469

APA StylePankoon, O., & Nimana, N. (2025). Delayed Star Subgradient Methods for Constrained Nondifferentiable Quasi-Convex Optimization. Algorithms, 18(8), 469. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18080469