Efficient Record Linkage in the Age of Large Language Models: The Critical Role of Blocking

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

3. Methodology

| Algorithm 1: Integrated Blocking-LLM Record Linkage |

|

3.1. Dataset Preparation

3.2. Blocking Algorithm

3.3. LLM Training

- Model loading: the base model is loaded from “unsloth/Meta-Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct-bnb-4bit” with quantization to reduce memory usage. The maximum sequence length is set to 2048 tokens.

- Parameter Efficient Fine-Tuning setup: LoRA(Low Rank Adaptation) is applied with rank (r = 16), alpha = 16, and dropout = 0.

- Training Configuration: Uses Supervised Fine-Tuning trainer from TRL library. Per device batch size = 2. Optimizer “adamw8bit” with learning rate = 2 , weight decay = 0.01.

- Tokenizer and Model loading: tokenizer and model loaded from “bert-base-uncased” with number of labels = 2

- Training Configuration: batch size per device = 4, gradient accumulation steps = 8, learning rate = 2 , weight decay = 0.01.

3.4. Pairwise Matching Within the Blocks

3.5. Record Linkage Output

4. Experimental Setup

- NVIDIA TITAN RTX GPU with an AMD Ryzen Threadripper 2950X 16-Core Processor. All experiments with Llama3.1 were performed on this environment.

- NVIDIA TITAN XP GPU (11.896 GB memory) with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-8400 CPU @ 2.80GHz. BERT experiments were performed with this environment.

4.1. Datasets

- FEBRL (Freely Extensible Biomedical Record Linkage): FEBRL [17] is perhaps the most widely used dataset for record linkage tasks. It consists of synthetically generated records, with introduction of errors such as misspellings, missing values, and typographical variations to simulate real-world scenarios. There are multiple versions of FEBRL available, such as febrl-1 through febrl-4. Each of them varies in size and error distribution. In our experiment, we used the febrl-4 dataset provided by recordlinkage package in Python. This contains two datasets to be linked along with the ground truth mapping of true matches.The febrl-4 dataset comprises 10,000 records in total: 5000 original records and 5000 duplicates, with exactly one duplicate per original to provide a controlled 1:1 matching structure and ground truth labels for evaluation. The attributes include first name, last name, address, suburb, date of birth, and Social Security ID. The duplicates incorporate realistic error types to mimic the data quality issues in real-world datasets. We selected febrl-4 over other versions like febrl-1 with 1000 records or febrl-3 with 3000 records due to its large-scale controlled duplicate structure.

- DS Dataset: To evaluate our algorithms, we utilized real-world data sourced from the Social Security Death Master File, provided by SSDMF.INFO [44]. Each record includes the following attributes: Social Security Number, last name, first name, date of birth, and date of death. To simulate realistic errors, we employed a modified version of the FEBRL dataset generator program to introduce variations into the data.

- OCR (Pseudopeople Dataset): This dataset is generated from the Pseudopeople library from Census, which generates large-scale simulated populations. It contains slightly over 10 million records of people in the state of Michigan. In this variant, 10% OCR errors were introduced in the first name and last name attributes, simulating character recognition mistakes.

- Phonetic (Pseudopeople Dataset): Similarly generated from the Pseudopeople library, this dataset introduces 10% phonetic errors in the first name and last name fields. These errors capture common variations in spellings due to phonetic similarities such as Smith vs Smyth. This makes it necessary to evaluate phonetic-based records linkage approaches.

- Typo (Pseudopeople Dataset): This dataset introduces 10% typographical errors in the first name and last name attributes. These types of errors are commonly observed in administrative databases.

- North Carolina Voter Dataset (NCV): The NCV [45] dataset contains five files, each containing one million voter records. Each file is source-consistent, meaning that within each file, there is only one record per entity. However, individuals may appear across multiple files. Some entities may be present in all the five files, others in two or three files, and some in only one file. This dataset is used in multi-source record linkage.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.3. Implementation Detail

- PyTorch with CUDA 12.2 for LLM training and interface.

- Transformers (Hugging Face) for loading and fine-tuning the LLaMA3 model.

- Unsloth library for efficient model loading and handling.

- tqdm for progress tracking and runtime monitoring.

- recordlinkage for dataset preparation and benchmark record linkage tasks.

- scikit-learn for computing evaluation metrics.

- Batch size: 4 per device

- Gradient accumulation: 8 steps

- learning rate: 2

- Number of epochs: 1

- Mixed-precision training: fp16

- Weight decay: 0.01

5. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| FEBRL | Freely Extensible Biomedical Record Linkage |

| NCV | North Carolina Voter dataset |

References

- Papadakis, G.; Ioannou, E.; Thanos, E.; Palpanas, T. Four Generations of Entity Resolution; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, N.; Soliman, A.; Basak, J.; Sahni, S.; Haase, K.; Mathur, A.; Park, K.; Weinberg, D.; White, J.; Rajasekaran, S. The Soundex Blocking: A Novel Blocking Approach for Record Linkage. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Washington, DC, USA, 15–18 December 2024; pp. 4039–4047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, N.; Basak, J.; Sahni, S.; Mathur, A.; Park, K.; Weinberg, D.; Rajasekaran, S. Double Metaphone Blocking: An Innovative Blocking Approach to Record Linkage. In International Symposium on Bioinformatics Research and Applications; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2025; pp. 139–150. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training. In Proceedings of the 2018 OpenAI Workshop, San Francisco, CA, USA, 24 September 2018; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, Z.; Ni, S.; Wang, Z.; Feng, X.; Li, C.; Hu, X.; Xu, R.; Yang, M.; Zhang, W. History, Development, and Principles of Large Language Models-An Introductory Survey. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.06853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xhst. Unstructured Record Linkage Using Siamese Networks and Large Language Models (LLMs). Available online: https://github.com/Xhst/ml-record-linkage (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Liu, M.; Roy, S.; Li, W.; Zhong, Z.; Sebe, N.; Ricci, E. Democratizing Fine-grained Visual Recognition with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 May 2024; Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=c7DND1iIgb (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Liu, H.; Zeng, S.; Deng, L.; Liu, T.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.-F. HPCTrans: Heterogeneous Plumage Cues-Aware Texton Correlation Representation for FBIC via Transformers. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, in press. [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Ma, J.; Wu, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, H. DSR-Net: Distinct Selective Rollback Queries for Road Cracks Detection with Detection Transformer. Digit. Signal Process. 2025, 164, 105266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enamorado, T.; Fifield, B.; Imai, K. Using a Probabilistic Model to Assist Merging of Large-Scale Administrative Records. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2019, 113, 404–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellegi, I.P.; Sunter, A.B. A Theory for Record Linkage. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1969, 64, 1183–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadinle, M.; Fienberg, S. A Generalized Fellegi-Sunter Framework for Multiple Record Linkage with Application to Homicide Record Systems. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 2013, 108, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enamorado, T.; Fifield, B.; Imai, K. FastLink: Fast Probabilistic Record Linkage with Missing Data. R Package, Version 0.6.1; CRAN: Vienna, Austria, 2019; Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=fastLink (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Ministry of Justice (MoJ). Splink: MoJ’s Open Source Library for Probabilistic Record Linkage at Scale. Version 1.0; GitHub: London, UK, 2021. Available online: https://github.com/moj-analytical-services/splink (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Christen, P.; Churches, T. FEBRL—Freely Extensible Biomedical Record Linkage. In Joint Computer Science Technical Report Series (Online); TRCS-02-05; Australian National University, Department of Computer Science: Canberra, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- FEBRL. Available online: http://sourceforge.net/projects/febrl/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Bell, A.G. The Deaf. In Special Reports: The Blind and the Deaf; U.S. Department of Commerce and Labor, Bureau of the Census, Eds.; U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1900. [Google Scholar]

- Box, J.F. R.A. Fisher, the Life of a Scientist; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Victor, T.W.; Mera, R.M. Record Linkage of Healthcare Insurance Claims. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2001, 84, 1409–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Sauleau, E.A.; Paumier, J.P.; Buemi, A. Medical Record Linkage in Health Information Systems by Approximate String Matching and Clustering. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2005, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmanabhan, S.; Carty, L.; Cameron, E.; Ghosh, R.E.; Williams, R.; Strongman, H. Approach to Record Linkage of Primary Care Data from Clinical Practice Research Datalink to Other Health-Related Patient Data: Overview and Implications. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2019, 34, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Labkoff, S.; Holliday, S.H. Opportunities for Electronic Health Record Data to Support Business Functions in the Pharmaceutical Industry—A Case Study from Pfizer, Inc. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2008, 15, 581–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christen, P. A Survey of Indexing Techniques for Scalable Record Linkage and Deduplication. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2012, 24, 1537–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadakis, G.; Skoutas, D.; Thanos, E.; Palpanas, T. Blocking and Filtering Techniques for Entity Resolution: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odell, M.; Russell, R. The Soundex Coding System. U.S. Patent US1261167A, 9 April 1918. [Google Scholar]

- Philips, L. The Double Metaphone Search Algorithm. C/C++ Users J. 2000, 18, 38–43. [Google Scholar]

- Christen, P. A Comparison of Phonetic Encoding Algorithms for Historical Name Matching. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM International Conference on Information and Knowledge Management (CIKM), Arlington, VA, USA, 6–11 November 2006; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Talburt, J.R.; Zhou, Y. Entity Resolution Using Double Metaphone in Commercial Datasets. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Information Reuse and Integration (IRI), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 4–6 August 2010; pp. 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Ong, T.C.; Mannino, M.V.; Schilling, L.M. Improving Record Linkage with Phonetic Algorithms in Healthcare. J. Biomed. Inform. 2014, 48, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Behm, A.; Ji, S.; Li, C.; Lu, J. Fuzzy Search with Double Metaphone for Approximate Matching. In Proceedings of the 25th IEEE International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Shanghai, China, 29 March–2 April 2009; pp. 456–461. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanzadeh, O.; Chiang, F.; Miller, R.J. Clustering Records with Double Metaphone: A Scalability Study. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Database Systems for Advanced Applications (DASFAA), Hong Kong, China, 22–25 April 2011; pp. 201–208. [Google Scholar]

- Gravano, L.; Ipeirotis, P.G.; Jagadish, H.V.; Koudas, N.; Muthukrishnan, S.; Srivastava, D. Approximate String Joins with Double Metaphone in Databases. VLDB J. 2003, 12, 345–364. [Google Scholar]

- Karakasidis, A.; Verykios, V.S. Privacy-Preserving Record Linkage Using Phonetic Codes. In Proceedings of the 13th Panhellenic Conference on Informatics (PCI), Corfu, Greece, 10–12 September 2009; pp. 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Mudgal, S.; Li, H.; Ko, T.; Srivastava, A.; Wang, R.; Mitra, S.; Srivatsa, S.; Popa, R.A.; Elmore, A.J.; Halevy, A. Deep Learning for Entity Matching: A Design Space Exploration. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Management of Data (SIGMOD’18), Houston, TX, USA, 10–15 June 2018; pp. 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, J.; Suhara, Y.; Doan, A.; Tan, W.-C. Deep Entity Matching with Pre-Trained Language Models. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2020, 14, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, I.; Koh, W.; Koo, B.; Kim, W.C. Network-based exploratory data analysis and explainable three-stage deep clustering for financial customer profiling. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 128, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deo, N.; Rajasekaran, S.; Kamel, R. Identifying Suitable Attributes for Record Linkage using Association Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (BigData), Sorrento, Italy, 15–18 December 2023; pp. 5753–5760. [Google Scholar]

- Meta AI. LLaMA 3.1 8B Instruct Model, Version 3.1; Meta: Menlo Park, CA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Liu, H.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Z. LDCNet: Limb Direction Cues-Aware Network for Flexible Human Pose Estimation in Industrial Behavioral Biometrics Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Informat. 2023, 20, 8068–8078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Liu, T.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.-F. EHPE: Skeleton Cues-Based Gaussian Coordinate Encoding for Efficient Human Pose Estimation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 26, 8464–8475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, C.; Deng, Y.; Xie, B.; Liu, T.; Li, Y.-F. TransIFC: Invariant Cues-Aware Feature Concentration Learning for Efficient Fine-Grained Bird Image Classification. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 27, 1677–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SSDMF Homepage. Available online: http://ssdmf.info/download.html (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- North Carolina State Board of Elections (NCSBE). Voter Registration Data. Available online: https://www.ncsbe.gov/results-data/voter-registration-data (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Revinate Engineering. CRM Data Pipeline Record Linkage (Part I). In Revinate Engineering Blog (Online); Revinate: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016; Available online: https://underthehood.meltwater.com/blog/2020/06/29/the-record-linking-pipeline-for-our-knowledge-graph-part-1/ (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Adler-Milstein, J.; Jha, A.K. Health Information Exchange among U.S. Hospitals: Who’s In, Who’s Out, and What Are the Implications? Health Aff. 2017, 36, 1420–1428. [Google Scholar]

| Dataset | Blocking | No Blocking |

|---|---|---|

| FEBRL | 96.03% | 91.24% |

| DS | 88.48% | 77.65% |

| OCR | 94.28% | 9.20% |

| Phonetic | 93.39% | 16.03% |

| Typo | 94.24% | 38.02% |

| NCV | 99.73% | 93.29% |

| Dataset | Blocking | No Blocking |

|---|---|---|

| FEBRL | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| DS | 89.57% | 100.00% |

| OCR | 94.12% | 13.63% |

| Phonetic | 93.91% | 22.67% |

| Typo | 94.12% | 45.09% |

| NCV | 98.32% | 50.23% |

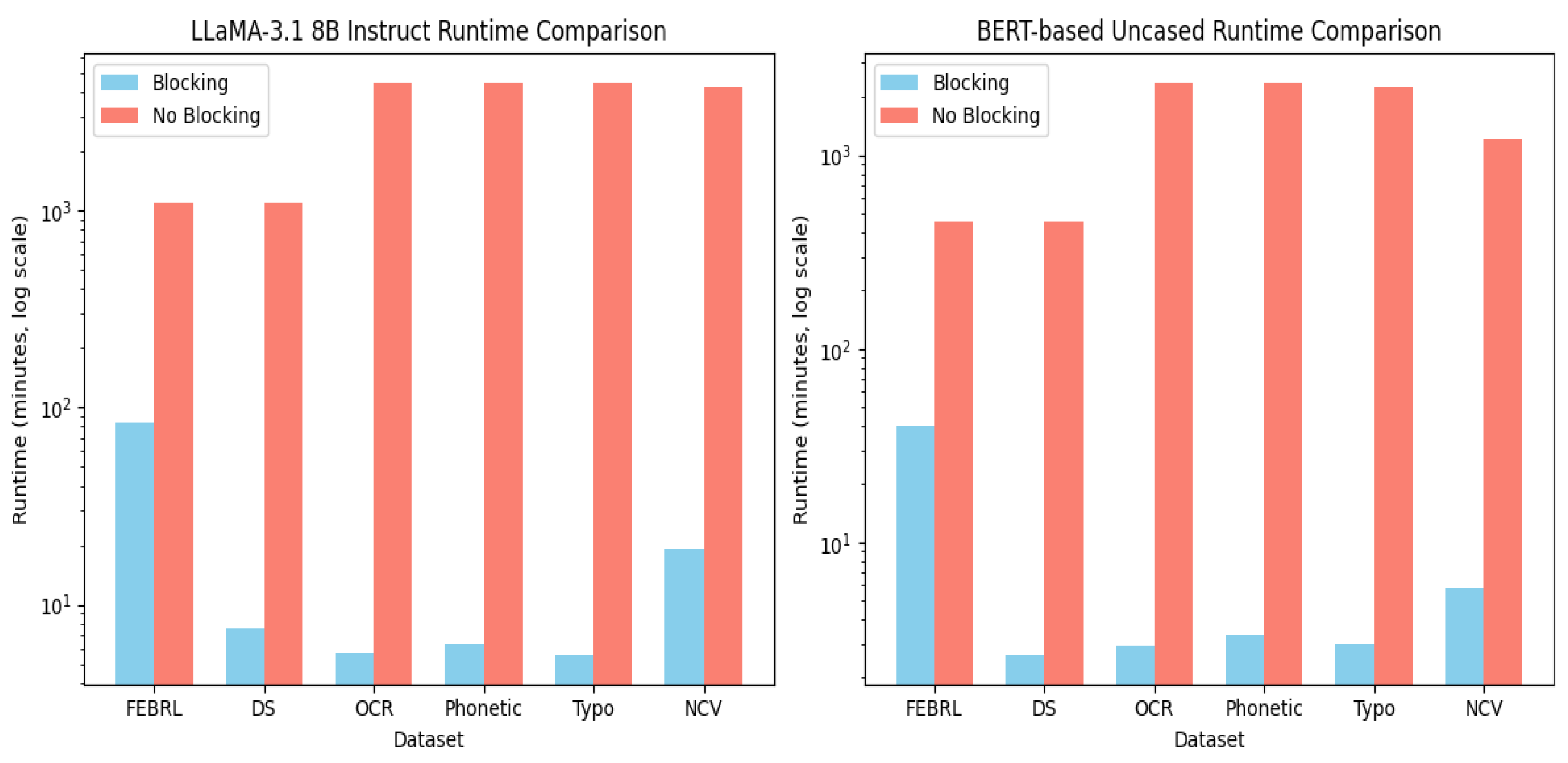

| Dataset | Blocking (Hours) | No Blocking (Hours) |

|---|---|---|

| FEBRL | 1:24:10 | 18:13:53 |

| DS | 0:07:37 | 18:14:09 |

| OCR | 0:05:35 | 73:58:48 |

| Phonetic | 0:06:19 | 73:52:18 |

| Typo | 0:05:31 | 74:38:55 |

| NCV | 0:19:02 | 70:51:55 |

| Dataset | Blocking (Hours) | No Blocking (Hours) |

|---|---|---|

| FEBRL | 0:40:10 | 7:37:02 |

| DS | 0:02:35 | 7:37:02 |

| OCR | 0:02:52 | 39:51:00 |

| Phonetic | 0:03:19 | 39:44:20 |

| Typo | 0:03:02 | 39:14:08 |

| NCV | 0:05:49 | 21:21:05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shah, N.; Patiyara, S.; Basak, J.; Sahni, S.; Mathur, A.; Park, K.; Rajasekaran, S. Efficient Record Linkage in the Age of Large Language Models: The Critical Role of Blocking. Algorithms 2025, 18, 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18110723

Shah N, Patiyara S, Basak J, Sahni S, Mathur A, Park K, Rajasekaran S. Efficient Record Linkage in the Age of Large Language Models: The Critical Role of Blocking. Algorithms. 2025; 18(11):723. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18110723

Chicago/Turabian StyleShah, Nidhibahen, Sreevar Patiyara, Joyanta Basak, Sartaj Sahni, Anup Mathur, Krista Park, and Sanguthevar Rajasekaran. 2025. "Efficient Record Linkage in the Age of Large Language Models: The Critical Role of Blocking" Algorithms 18, no. 11: 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18110723

APA StyleShah, N., Patiyara, S., Basak, J., Sahni, S., Mathur, A., Park, K., & Rajasekaran, S. (2025). Efficient Record Linkage in the Age of Large Language Models: The Critical Role of Blocking. Algorithms, 18(11), 723. https://doi.org/10.3390/a18110723