Abstract

The diagnosis of faults in induction motors, such as broken rotor bars, is critical for preventing costly emergency shutdowns and production losses. The complexity of this task lies in the diversity of induction motor operating regimes. Specifically, a change in load alters the signal’s frequency composition and, consequently, the values of fault diagnostic features. Developing a reliable diagnostic model requires data covering the entire range of motor loads, but the volume of available experimental data is often limited. This work investigates a data augmentation method based on the physical relationship between the frequency content of diagnostic signals and the motor’s operating regime. The method enables stretching and compression of the signal in the spectral domain while preserving Fourier transform symmetry and energy consistency, facilitating the generation of synthetic data for various load regimes. We evaluated the method on experimental data from a 0.37 kW induction motor with broken rotor bars. The synthetic data were used to train three diagnostic models: a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and a hybrid CNN-MLP model. Results indicate that the proposed augmentation method enhances classification quality across different load levels. The hybrid CNN-MLP model achieved the best performance, with an F1-score of 0.98 when augmentation was employed. These findings demonstrate the practical efficacy of physics-guided spectral augmentation for induction motor fault diagnosis.

1. Introduction

Electric motors represent a critically important class of electrical equipment in modern industrial processes. According to various estimates, they account for up to 50% of global electricity consumption [1,2]. Induction motors (IM) predominate in this category, constituting up to 90% of the total motor population [3,4]. IMs provide operation for equipment in various commercial and industrial applications, including supply ventilation systems, pumping units, conveyor lines, lifting mechanisms, metalworking machine tools, electric and hybrid vehicles [5].

IMs possess high structural reliability. Despite this, prolonged exposure to adverse operational factors can lead to mechanical and electrical damage. Unforeseen IM failures lead to substantial financial losses due to unplanned production line downtime. Failures of unique, high-power IMs (up to several megawatts) are particularly critical, as they typically have no redundancy. The dismantling and replacement of such motors require significant costs due to their large size and complex design. These specificities necessitate increased attention from researchers to the challenges of ensuring IM fault tolerance [6].

A broken rotor bar is one of the most critical faults in an IM [7]. Operating an IM with this defect leads to a number of negative consequences: increased energy consumption, reduced torque, and a higher overall vibration level. Particularly severe damage scenarios involve fragments of the broken bar entering the air gap between the stator and rotor, causing the rotor to lock and damaging the stator winding [8]. Therefore, the timely diagnosis of this type of fault is critically important.

A broken bar (BB) leads to an asymmetry in the resistance and inductance of the rotor circuit. This results in an uneven distribution of currents in the rotor bars. This phenomenon causes the formation of an additional magnetic field, rotating in the opposite direction relative to the motor’s main field [9]. This effect leads to the amplitude modulation of the stator current:

where is the fundamental supply frequency, and are the amplitude and phase of the k-th supply harmonic with frequency , m is the modulation index,

is the modulating rotor fault harmonic, , , are the amplitude, frequency, and phase of the rotor fault harmonic, represents other components/noise.

The frequency of the rotor fault harmonic, , can be calculated using the formula:

where is the motor slip, is the rotational speed of the rotor, is the harmonic order.

The motor slip represents the relative difference between the rotational speed of the rotor and the motor’s magnetic field speed and depends on the load applied to the shaft. The greater the load, the greater the electromagnetic torque required to overcome the load torque. The increase in torque is achieved by raising the rotor current, which requires a greater lag (slip) to induce the necessary EMF. Under rated conditions, the slip typically ranges from 0.02 to 0.1, depending on the motor’s design. Consequently, for k = 1, the frequency can range from 0.4 Hz to 10 Hz as the supply frequency varies from 10 Hz to 50 Hz, respectively.

The amplitudes of the rotor fault harmonics can be used as diagnostic indicators. The amplitudes of the fault harmonics around the fundamental supply frequency, , are most commonly used as a diagnostic indicator because their energy is higher compared to other harmonic components [10]. Higher-order rotor fault harmonics in the vicinity of the 5th and 7th supply harmonics, and , can also be utilized [11,12,13,14]. A key advantage of higher harmonics lies in their resilience to masking effects, such as load torque oscillations, rotor magnetic anisotropy, and non-adjacent broken bars. The number of significant higher harmonics can range from 1 to 4, with their amplitude correlating with the severity of the rotor damage [15].

Traditional diagnostic methods based on frequency-domain signal analysis demonstrate sufficient effectiveness under controlled conditions. However, their sensitivity to varying operating conditions and the need for expert knowledge to interpret the results have stimulated the development of machine learning methods. Modern diagnostic approaches rely on the capability of neural networks to automatically identify complex patterns in data, thereby overcoming the limitations of classical techniques.

These data-driven approaches can be broadly categorized based on their input data type. Methods based on time series analysis [16] primarily rely on recurrent architectures and demonstrate comparatively lower accuracy [17]. Approaches that utilize statistical and spectral features extracted from time series often prove to be more informative and are implemented using Multilayer Perceptrons (MLP) [18]. However, these methods are limited in their ability to extract complex non-linear dependencies from raw signals. This limitation is overcome by methods that involve transforming time series into two-dimensional representations with subsequent analysis by Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) [19,20,21,22]. The choice of an optimal data preprocessing method is a key challenge for CNN-based approaches. The combination of both approaches in hybrid architectures is a logical evolution, integrating image analysis and numerical features. This allows for improved classification accuracy [23,24,25].

Despite the promise of neural networks, their application in industrial settings is hampered by the scarcity of labeled training data [26]. The training dataset must representatively cover all possible equipment operating regimes, including both healthy and faulty states. However, collecting data across the entire range of operating regimes under real industrial conditions is an extremely labor-intensive task. Furthermore, obtaining data for rare fault conditions often proves to be practically impossible. Consequently, the generation of synthetic signals has become a primary approach to solving the data scarcity problem.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) are the most prevalent method for synthetic data generation [27,28]. This approach is based on the adversarial training of two neural networks: a generator, which creates synthetic samples, and a discriminator, which distinguishes real data from generated data. However, standard GAN architectures primarily compensate for the imbalance in an existing dataset but do not enable the generation of data for fundamentally new operating conditions or faults that are absent from the training set.

Time series augmentation methods represent an alternative approach [29]. Techniques such as adding Gaussian noise, time warping, random amplitude scaling, and applying random convolutional kernels are common methods for creating new data based on existing samples [30]. However, while these methods are effective for increasing data diversity, they do not ensure the physical plausibility of the generated signals. They fail to account for the actual physical processes within an induction motor, such as variations in magnetic flux, slip, or rotor circuit parameters, which significantly limits their reliability in practical applications. The development of physically grounded augmentation methods that consider the electromagnetic and mechanical processes in an induction motor appears to be a promising direction. Such an approach would ensure both data diversity and adherence to real physical principles.

An example of physically grounded data augmentation for induction motors is presented in [31]. Random filtering was applied to simulate spectral changes in the vicinity of the supply harmonic. In our previous work [32], an alternative signal augmentation method was proposed, based on compressing/stretching segments of the current spectrum from a faulty induction motor to align with various load levels. While [32] introduced the core warping concept and validated it on a specific CNN, the present study provides a comprehensive multi-architecture benchmark and a deeper analytical validation of the method’s ability to replicate data distributions across unseen operational regimes. The theoretical foundation of the method lies in utilizing the dependence of the rotor fault frequency components (1) on the motor slip, which, in turn, depends on the load. A key advantage of this approach is the establishment of a direct link between the augmentation parameters and the mechanical characteristic of the induction motor. This allows for the pre-calculation of the degree of spectral transformations required to achieve the target frequency characteristics of the fault harmonics for a given load level.

While preliminary research into a spectral warping approach showed promise for a specific CNN architecture [32], its broader applicability and synergy with diverse model types remained an open question. Furthermore, a comprehensive evaluation across different input data modalities and a rigorous analysis of the augmentation’s impact on the feature space were lacking. This work presents a comprehensive evaluation of the physically grounded time series augmentation method in combination with different classifier architectures: a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and a hybrid model with mixed input (Hybrid-CNN-MLP). Visualization of the augmentation results for different induction motor load regimes is implemented using a cascaded dimensionality reduction method. The effectiveness of the proposed method is demonstrated on experimental data from an induction motor with broken rotor bars under varying load scenarios.

The principal contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- A Novel Physics-Guided Spectral Augmentation Algorithm: We introduce a data augmentation technique that strategically warps the current signal spectrum based on the motor’s electromechanical principles (load-slip relationship) to generate physically plausible data for unseen operational regimes.

- (2)

- A Comprehensive Multi-Architecture Benchmark: We present a rigorous comparative study evaluating the synergy of the proposed augmentation with three fundamentally different model types: a feature-based MLP, an image-based CNN, and a novel Hybrid CNN-MLP model.

- (3)

- A Novel Hybrid CNN-MLP Diagnostic Model: We design and validate a hybrid architecture that effectively fuses hand-crafted statistical features with learned representations from time-series images, demonstrating superior and balanced performance.

- (4)

- In-Depth Analytical Validation: We employ feature space visualization to analytically demonstrate how the augmentation replicates the data distribution of missing operational regimes, providing explainability for the performance gains.

While this manuscript demonstrates the effectiveness of several neural network classifiers, including a novel hybrid CNN-MLP architecture, its primary contribution lies in the development of a novel physics-guided spectral augmentation technique. This method addresses the core industrial challenge of data scarcity by generating physically plausible data for operational regimes absent from the experimental dataset. The classifiers, and particularly the performance gains of the hybrid model, serve as a rigorous benchmark to validate the practical value of the proposed augmentation method.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 details the materials and methods, including signal preprocessing, feature vector extraction for the MLP, transformation of time series into Gramian Angular Field (GAF) images for the CNN, and the physics-guided spectral augmentation technique. Section 3 presents the experimental results and a comparative analysis of the MLP, CNN, and hybrid CNN-MLP models. Section 4 provides a comprehensive discussion of the findings and the study’s limitations. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper by summarizing the principal outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

This section details the materials and methods employed in the study. It comprehensively outlines the signal preprocessing pipeline, the formation of numerical feature vectors for the MLP and two-dimensional representations for the CNN, and introduces the core physics-guided spectral augmentation algorithm. The described methodologies form the foundation for the subsequent experimental evaluation.

2.1. Data Preprocessing

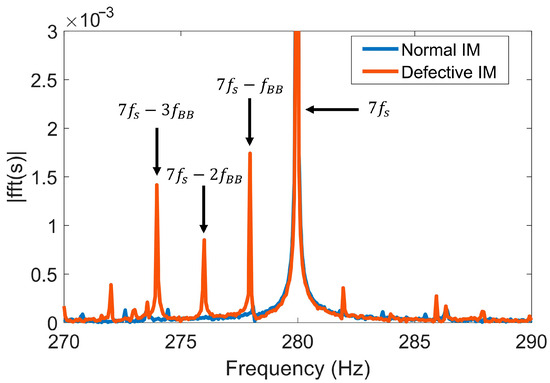

Higher-order rotor fault harmonics, extracted from the induction motor stator current signals in the vicinity of the seventh supply harmonic frequency , are used as diagnostic indicators (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Stator current spectra near the 7th supply harmonic () for the healthy and faulty induction motor conditions.

Analysis of Figure 1 shows that extracting these specific harmonics from the raw signal requires the application of a band-pass filter. The passband of this filter must encompass, at a minimum, the frequency components , , and . As a result of filtering current signal segments of a fixed length, signals were formed that contained exclusively the seventh supply harmonic and its associated higher-order fault harmonics.

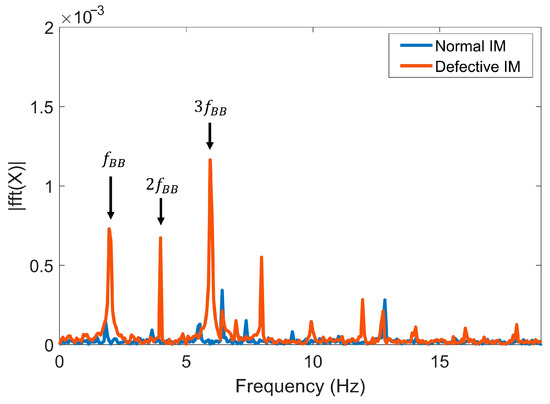

Subsequently, using the Hilbert transform, envelopes are generated from the filtered signals. These envelopes contain low-frequency harmonics at the frequencies , , and (Figure 2). Thus, the resulting envelopes possess enhanced diagnostic information compared to the original signals.

Figure 2.

Envelope spectra obtained after band-pass filtering and Hilbert transform, revealing the low-frequency fault harmonics.

The analysis of the envelopes, which are time series, was performed using two complementary approaches: numerical feature vector analysis and two-dimensional representation analysis. The feature vectors, which include the most informative temporal and spectral characteristics of the signals, were intended for subsequent training of a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP). The two-dimensional representations of the envelopes, which facilitate the identification of spatial patterns that are difficult to describe numerically, were used for training a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). Combining both approaches made it possible to significantly improve the accuracy of detecting broken rotor bars in an induction motor.

2.2. Formation of the Numerical Feature Vector

The selection of informative features is a key challenge in building diagnostic models based on feature vectors. In this work, rather than employing classical filter methods based on predefined criteria such as trendability and monotonicity [33,34] or correlation analysis [35,36], we utilized a model-embedded feature selection mechanism. This approach leverages a Random Forest classifier, whose proven effectiveness for this task is supported by comparative studies [37].

A step-by-step procedure was implemented to construct the feature vector for the MLP. In the first stage, the TSFEL library [38] was used to extract an extensive set of signal characteristics, including temporal, spectral, statistical, and fractal features, ensuring the formation of a nearly exhaustive list of potentially relevant features without manual selection. The next stage involved filtering out features directly tied to fixed frequency components in the signals. Such characteristics, particularly integral spectral metrics in the vicinity of a specific frequency, can lose diagnostic informativeness when the induction motor’s operating conditions change, thereby negatively affecting model robustness. The final stage entailed the selection of the most significant features using a Random Forest model, where the separation effectiveness was evaluated using the Gini impurity criterion:

where X is the set of objects in the given tree node, k is the number of classes, and is the proportion of elements of the k-th class in the node. The quantitative measure of a feature’s importance at the individual tree level is determined by the decrease in impurity after splitting the data based on that feature. The final feature importance score is computed by averaging across all trees in the ensemble. Features whose importance exceeded the median value across the entire set were retained for the final selection.

The application of this procedure significantly reduces the dimensionality of the feature space, minimizes data redundancy, and enhances the model’s robustness to variations in operational conditions. The specific outcome of this feature selection process for our experimental dataset is reported in Section 3.2.

2.3. Formation of Two-Dimensional Representations

Methods based on the use of two-dimensional time series representations initially evolved from classical time-frequency analysis approaches, such as the Short-Time Fourier Transform [21] and the Continuous Wavelet Transform [22]. Despite the potential for high diagnostic accuracy, the practical application of these methods is limited by their significant computational complexity [39].

As an alternative, more computationally efficient methods for converting signals into their two-dimensional representations have been developed. In particular, the Markov Transition Field (MTF) method, introduced in 2015 [40], has demonstrated effectiveness in bearing diagnostics [41] and servo motor diagnostics [42]. Similarly, Recurrence Plots (RP) [43], which provide a visualization of temporal dependencies and periodic patterns in data, were successfully applied to induction motor diagnostics using vibration signals [44] and for condition assessment of synchronous motors using current signals [45].

The Gramian Angular Field (GAF) method [46] has also found application in various diagnostic tasks, including bearing condition monitoring using vibration signals [41], fault detection in planetary gearboxes [47], and rotor eccentricity detection in induction motors [48]. An important advantage of the GAF method is its ability to visualize subtle fault signatures that may remain undetected when using wavelet transform [49], ultimately contributing to improved classification accuracy.

The GAF method transforms a time series into a polar coordinate system. The original sequence of signal samples, , is scaled to the interval [–1, 1] according to the expression:

The scaled values are then converted into polar coordinates:

where represents the time index and N is the length of the time series.

After encoding the time series samples into polar coordinates, the cross-correlation between all possible pairs of points i and j can be computed, yielding a square matrix of size N × N:

Similarly, the matrix can be constructed, which also carries diagnostic information about the signal:

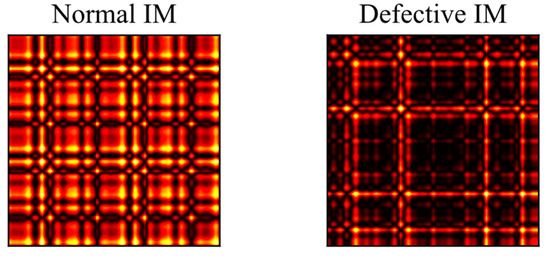

The visual patterns produced by the GASF (Gramian Angular Summation Field) and GADF (Gramian Angular Difference Field) methods exhibit a high degree of similarity, making it sufficient to use only one of them. Figure 3 shows GASF images corresponding to the healthy and faulty states of the induction motor. Henceforth, the term GAF implies the construction of GASF images.

Figure 3.

GASF image representations of the preprocessed current signals for the healthy and faulty motor conditions.

Having established the methods for creating both numerical feature vectors and image-based representations, the following section addresses the critical challenge of data scarcity by introducing a physics-guided augmentation technique.

2.4. Evaluation of Augmentation Parameters

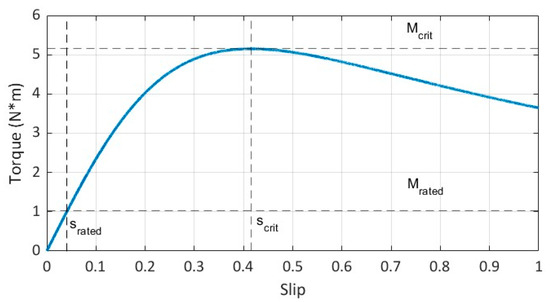

The primary challenge in IM diagnostics is that changes in operating conditions lead to variations in the system’s physical parameters and, consequently, in the acquired signals. This is primarily manifested as a shift in the frequencies of fault-related harmonics in the current spectrum, the values of which depend on the slip (1). The motor slip can be estimated from its torque-speed characteristic. This characteristic may be provided in the motor’s technical data sheet or approximated using Kloss’s formula [9]:

where is the critical (maximum) motor torque, and is the critical slip.

The values of and can be calculated using the formulas:

where is the maximum torque ratio, is the rated motor torque, and is the rated motor slip. Typically, all three parameters are provided in the motor’s technical data sheet. An example of a torque-speed characteristic calculated using Kloss’s formula is shown in Figure 4. The IM parameters are power 0.37 kW, = 1.02 N·m, = 0.042, = 5. The slip increases almost linearly with the torque in the operating zone and then rises sharply as it approaches the critical torque.

Figure 4.

Motor torque-speed characteristic (calculated from technical data via Kloss’s formula), which provides the slip-load relationship essential for the spectral warping algorithm.

Thus, given the mechanical characteristic and knowing the load torque, the induction motor slip can be estimated. The following section presents an augmentation method that enables the generation of a synthetic dataset accounting for variations in slip. This dataset will be used to train neural network models, thereby compensating for the data scarcity in the original training set.

2.5. Data Augmentation Method

The augmentation method operates directly in the frequency domain, as the key effect of a changing load—the shift in fault harmonic frequencies—is most naturally and efficiently represented in the spectral domain. Therefore, the method is based on transforming the current signal spectrum obtained via the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), which provides the necessary frequency representation for the subsequent spectral warping procedure. The core idea of the method is to simulate the effect of induction motor slip on the current spectrum by modifying the spectral regions containing the rotor fault harmonics. This approach artificially generates new signals corresponding to various motor load conditions without the need for physical experiments.

The value of the coefficients for an N-point Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) of a signal is given by the formula:

The signal s can be reconstructed from its spectrum via the Inverse DFT:

The DFT of a real-valued signal possesses the property of conjugate symmetry:

where * denotes the complex conjugate operation.

The value of the coefficients of the complex discrete function from expression (2) can be written in exponential form:

where , are the values of the amplitude and phase spectrum coefficients, respectively.

From property (3), the following symmetry properties follow:

Let the spectral interval of the preprocessed current signals with rotor fault harmonics correspond to the coefficients with indices . When the load changes, the slip changes by a factor of p, leading to a change in the interval of interest to , where . The general case with variable left and right interval boundaries will be considered hereafter.

To simulate an increase (decrease) in load, it is necessary to stretch (compress) the spectrum of the original signal on the interval to a new interval . Concurrently, to preserve integrity, the spectrum on the interval is compressed (stretched) to the new interval . Thus, only the DFT coefficients with indices are altered, which corresponds to a restructuring in the frequency range:

where Fs is the sampling frequency. Due to the symmetry property (4), the complex conjugate part of the spectrum must also be restructured. The step-by-step augmentation Algorithm 1 is presented next.

| Algorithm 1. Physically Grounded Spectral Warping Algorithm |

| Input: Discrete-time signal sampling frequency frequency bin indices , where and Definitions:

|

| Compute the DFT of the input signal: Warp the lower spectral segment

|

Warp the upper spectral segment

|

| Merge warped segments into a continuous spectrum block: To avoid duplication at bin c, use one of the following stitching strategies: |

| or |

| Update the DFT spectrum in the target range. Replace the original coefficients: |

| . |

| if then |

| else |

| end return the modified spectrum S |

The following section demonstrates the effectiveness of this method when used with different diagnostic models under several load variation scenarios.

3. Results

This section presents and analyzes the results of the experimental study. The efficacy of the proposed data augmentation method is evaluated by comparing the performance of three diagnostic models—MLP, CNN, and the hybrid CNN-MLP—trained on both the original and the augmented synthetic datasets. Data distribution visualizations and F1-score metrics are employed to demonstrate the impact of augmentation on the classification quality across different load regimes.

To ensure statistical reliability and a fair comparison, all models (MLP, CNN, and Hybrid CNN-MLP) were trained using an identical set of hyperparameters over 10 independent runs with random weight initialization. The reported results represent the averaged performance metrics across these runs. The unified training configuration was as follows: optimizer: Adam; learning rate: 0.0001; loss function: Categorical Cross-entropy; batch size: 100; maximum epochs: 500; weight initialization: Glorot Uniform; early stopping: monitored ‘val_loss’ with a patience of 30 epochs. This consistent setup allows for a direct and reproducible evaluation of the models’ performance and the impact of the proposed augmentation method.

3.1. Experimental Dataset

The current signals were acquired from an experimental test rig featuring a two-pole Marathon Electric D391 induction motor with a rated power of 0.37 kW. The motor load was adjusted using a magnetic brake and set at three levels: L1 = 2%, L2 = 20%, and L3 = 36% of the motor’s rated torque. The supply voltage frequency was varied from 20 to 50 Hz in 10 Hz discrete steps using a variable-frequency drive (VFD). Current signal measurement was performed using a current clamp fixed on the motor’s phase conductor. Although all three phase currents were measured, the signal from a single phase was used for the subsequent analysis. This approach is standard in Motor Current Signature Analysis (MCSA), as symmetrical rotor faults like broken bars manifest identically in all three phases, making the information from one phase sufficient for reliable detection [50].

The measurements were taken for two explicitly defined conditions: the healthy state (normal data), referring to a motor with no introduced faults, and the faulty state (defective data), corresponding to a motor with three broken rotor bars. The total acquired dataset comprised 24 time-domain signals, each 60 s long, recorded at a sampling frequency of 50 kHz.

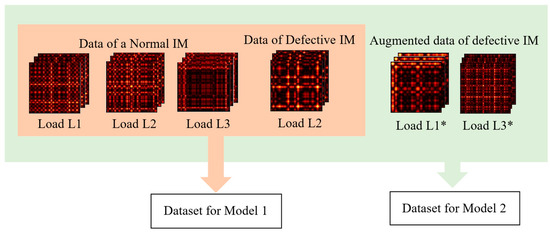

To compare the effectiveness of training on the original versus the augmented data, two models with identical architecture were trained: Model 1 was trained on the original limited dataset, and Model 2 was trained on the extended dataset, which included synthetic data (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Training data strategy: Model 1 uses only original data, while Model 2 is supplemented with synthetic samples (L1*, L3*) generated via augmentation.

The composition of the training datasets for Model 1 (original data) and Model 2 (augmented data) is detailed in Table 1 and Table 2. A key limitation of the original dataset is that faulty motor data is available only for the medium load L2. This means Model 1 cannot learn the manifestation of the fault under low (L1) or high (L3) load conditions.

Table 1.

Training Data Composition for Model 1: Original dataset with faulty data available only at load L2.

Table 2.

Training Data Composition for Model 2: Augmented dataset with synthetic faulty data for loads L1 and L3.

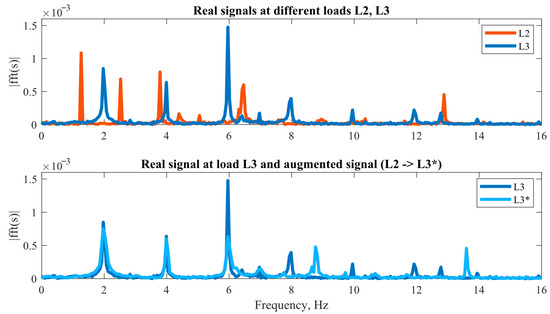

The augmented dataset (for Model 2) addresses this by using spectral warping to generate physically realistic faulty data for the missing low and high load regimes (L1*, L3*), ensuring the model is trained on a comprehensive set of operational conditions. Figure 6 provides a visual comparison of the real and synthetic signal spectra, validating the augmentation approach.

Figure 6.

Visual validation of the spectral augmentation. Upper: Spectra of real faulty motor signals at the original load levels L2 and L3, showing the inherent difference. Lower: Comparison between the spectrum of a real L3 signal and the synthetic L3 signal generated by augmenting a real L2 signal, demonstrating their close alignment.

The most significant difference between the spectra is observed in the amplitude of the frequency components, which is attributed to the inherent disparity in the spectral composition of signals corresponding to different motor loads. While the augmentation method mitigates the dominant discrepancies between the signals, it does not ensure precise replication of the spectral characteristics.

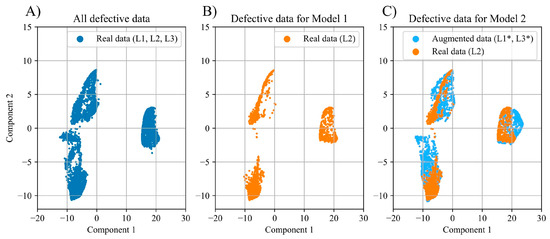

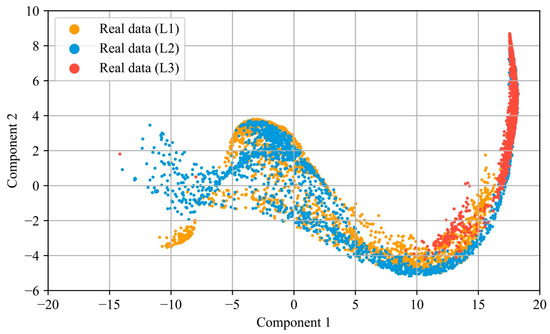

The effectiveness of supplementing the limited dataset with synthetic signals is demonstrated by visualizing the distributions of the preprocessed experimental data in Figure 7 and Figure 8. Figure 7 presents two-dimensional distributions of the numerical feature vectors, extracted from the faulty motor signals using the methodology described in Section 2.2. The visualization was generated using the PaCMAP dimensionality reduction technique [51]. Figure 7A shows the distribution of the real faulty data across three load levels. Utilizing data from only a single load level (Figure 7B) results in a distribution that is markedly different from the original. The application of augmentation to generate signals for the missing load levels produces a distribution with a high degree of similarity to the original, comprehensive dataset (Figure 7C).

Figure 7.

Low-dimensional projection (via PaCMAP) of the numerical feature vectors for the faulty motor signals under different load conditions. (A) Real data for all loads (L1, L2, L3). (B) Real data for L2 only. (C) Real (L2) and augmented data (L1*, L3*).

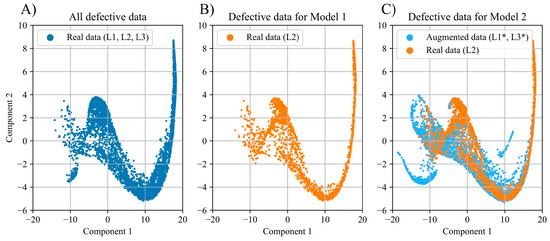

Figure 8.

Low-dimensional projection (via PaCMAP) of the GAF image embeddings for the faulty motor signals under different load conditions. (A) Real data for all loads (L1, L2, L3). (B) Real data for L2 only. (C) Real (L2) and augmented data (L1*, L3*).

To construct the distributions shown in Figure 8, the GAF images were mapped into vectors comprising 128 features by training a convolutional autoencoder model. Subsequently, using the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) method, the resulting vectors were projected onto the 32 most informative numerical values, which were visualized as two-dimensional representations using the PaCMAP method. The low-dimensional projections in Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 were generated using the PaCMAP algorithm [51]. The visualization used a standard set of parameters that robustly preserved the data structure across all conditions: n_neighbors = 200, MN_ratio = 0.5, FP_ratio = 2.0, and the Euclidean distance metric.

Figure 9.

Low-dimensional projection (via PaCMAP) of the GAF image dataset for all load levels (L1, L2, L3).

For the distributions based on the GAF images, the same trends are observed as in the case of the numerical feature vectors. The use of augmentation similarly enables the replication of the distribution of the real data for the faulty induction motor.

3.2. Results for MLP Model

The input data for MLP were the numerical feature vectors constructed using the methodology described in Section 2.2. Initially, 88 features were extracted from the preprocessed data. After feature selection using the Random Forest algorithm, the number of features was reduced to 43. The final numerical feature vector included statistical measures (including the median), spectral characteristics (median frequency, spectral entropy), as well as Linear Predictive Cepstral Coefficients (LPCC) and Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients (MFCC).

The MLP architecture consisted of three hidden fully connected layers with 32, 16, and 8 neurons, respectively, using the ReLU activation function. To improve the model’s generalization ability, regularization techniques—Dropout and Batch Normalization layers—were applied after each hidden layer. The remaining training hyperparameters followed the unified configuration described above.

To ensure statistical reliability, the MLP models were trained and tested over 10 runs. Table 3 compares their averaged F1-score performance on the critical test cases: low (L1) and high (L3) load levels.

Table 3.

F1-score of the MLP model trained on different datasets.

For Model 1, these represent challenging, unseen conditions during training, while Model 2 was exposed to their synthetic counterparts (L1*, L3*). As shown in Table 3, the results indicate that while augmentation provided a marginal benefit for the low-load condition (L1), it yielded a substantial improvement for the high-load condition (L3), where the F1-score increased dramatically from 0.55 to 0.88.

3.3. Results for CNN Model

The dimensionality of the input GAF images for the CNN was 128 × 128 × 1 (monochrome format). The network architecture consisted of three sequential convolutional blocks, each comprising: a 2D convolution operation with a 5 × 5 kernel (with 32, 64, and 128 filters, respectively), a ReLU activation function, a Batch Normalization layer, and a subsampling operation (MaxPooling with a 2 × 2 kernel). Following the sequence of convolutional layers, the multidimensional feature maps were transformed into a one-dimensional vector using a Flatten operation. Classification was performed by a two-level fully connected classifier, consisting of layers with 2048 and 128 neurons with ReLU activation and Dropout regularization, supplemented by an additional hidden layer with 32 neurons. The network’s output layer contained two neurons with a softmax activation function, corresponding to the binary classification task, analogous to the MLP model architecture. The remaining training hyperparameters followed the unified configuration described above.

Model 1 and Model 2 with the CNN architecture were also trained and tested 10 times. Table 4 presents the averaged F1-score values.

Table 4.

F1-score of the CNN model trained on different datasets.

Comparison with the MLP architecture results demonstrates that without augmenting the training set with synthetic data, the CNN architecture exhibits lower classification accuracy, particularly under high load conditions where the F1-score drops to 0.31. However, the introduction of augmented data leads to a significant improvement in classification quality: under low load, the model achieves an F1-score of 0.98, and under high load, 0.78. Thus, the improvement in classification accuracy is more substantial for the CNN compared to the MLP, confirming the effectiveness of using data augmentation in combination with GAF images and convolutional architectures. Nevertheless, despite the substantial improvement, the absolute metric values under high load remain lower than those under low load.

For both architectures, MLP and CNN, a significant imbalance in classification accuracy in favor of low-load conditions is observed, which persists even after applying augmentation. This phenomenon can be explained by the characteristics of the data distribution in the original dataset (Figure 9). Analysis of the distribution reveals that the data corresponding to load L2 exhibit greater proximity to the data under load L1 than to L3, leading to a systematic decrease in classification accuracy for high-load L3 conditions.

A comparative analysis of the MLP and CNN approaches demonstrates the superiority of the former under conditions of no data augmentation, particularly in terms of the classification accuracy gain for high-load data. In contrast, CNN without augmentation shows a significant decrease in effectiveness, especially on data corresponding to high load. The application of augmentation allows the CNN approach to achieve a significant improvement in accuracy metrics, exceeding the MLP performance on low-load data. This observation motivated the development of a hybrid architecture that integrates both types of input data: numerical feature vectors and GAF images.

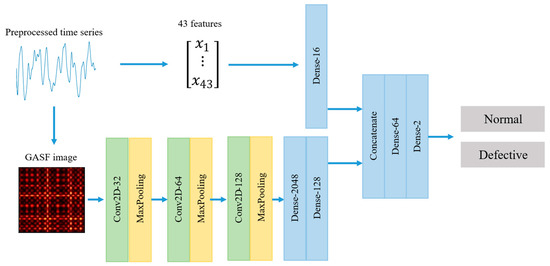

3.4. Results for Hybrid CNN-MLP Model

The hybrid model incorporates two data processing branches: one based on convolutional layers (CNN) for analyzing GAF images, and another based on fully connected layers (MLP) for processing the vector of statistical features. The complete model architecture is presented in Figure 10. Subsequently, the output representations from both channels are combined and passed through several fully connected layers, enabling the model to account for both the time-frequency structure of the signal and the aggregated numerical characteristics. This approach facilitates the formation of a comprehensive feature space capable of compensating for the limitations of individual architectures. The model was trained using the unified configuration described above, which included the hyperparameters and the procedure of 10 independent runs. The testing results for the hybrid model are presented in Table 5.

Figure 10.

Architecture of the proposed Hybrid CNN-MLP model for multi-input fault diagnosis.

Table 5.

F1-score of the Hybrid CNN-MLP model trained on different datasets.

In the absence of augmentation, the hybrid architecture demonstrated results that correlated with the CNN approach but with a lower level of accuracy: under high load, a significant degradation in classification quality was observed (F1 = 0.27), while for low load, relatively high effectiveness was maintained (F1 = 0.91). The use of augmented data not only balanced the performance metrics across different load conditions but also achieved higher values: F1 = 0.98 for low load and F1 = 0.89 for high load. Thus, data augmentation played a critically important role specifically in the context of the hybrid architecture, delivering a substantial gain in accuracy and outperforming both the CNN and MLP models. This result indicates that the full potential of the physics-guided augmentation method is realized when it is coupled with a hybrid architecture that can leverage combined data representations.

4. Discussion

This study set out to validate a physics-guided spectral augmentation method and evaluate its synergy with various neural network architectures for IM fault diagnosis under variable load conditions. The experimental results lead to several key findings and implications.

4.1. The Impact of Physics-Guided Augmentation

The core finding of this work is that the proposed spectral warping method effectively mitigates the data scarcity problem for unseen operational regimes. The visual evidence in Figure 7 and Figure 8 demonstrates that the augmented data (for loads L1* and L3*) closely approximate the distribution of real experimental data across both feature-vector and image-based representations. This successful distribution alignment is the fundamental reason for the significant performance gains observed in Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, particularly for the high-load (L3) condition, which was entirely absent from the original faulty training set.

The method’s superiority over naive augmentation techniques (e.g., adding noise or time-warping) lies in its grounding in the motor’s electromechanical principles. By explicitly modeling the relationship between load, slip, and the frequency of fault-related harmonics, the augmentation generates physically plausible data. This ensures that the synthetic samples lie on the true, albeit estimated, data manifold of the motor’s behavior, which is a more reliable approach for enhancing model robustness than data-agnostic methods [29,30].

4.2. Comparative Analysis of Model Architectures

Before proceeding to the comparative analysis, it is crucial to clarify the nature of the synergy in the hybrid model. Although the CNN and MLP branches process the same source signal (the envelope), they operate on fundamentally different representations of it, which carry complementary information.

The MLP branch works with engineered features—a quantitative description of the signal obtained by calculating its statistical and spectral characteristics. This can be viewed as an “expert’s verbal description” of the signal, highlighting its pre-defined, physically interpretable properties. In contrast, the CNN branch analyzes GAF images—a structural representation of temporal correlations in a form suitable for visual pattern recognition. This approach allows the model to autonomously discover complex, often non-obvious spatial dependencies that are difficult to capture with a fixed set of formulas.

Therefore, the fundamental reason for the hybrid model’s effectiveness lies not in processing different data, but in the fusion of two analytical paradigms: an expert-driven approach (via features) and an exploratory, data-driven approach (via visual patterns). This combination creates a more comprehensive and robust feature space than any single paradigm could achieve alone.

The performance of the different models, with and without augmentation, reveals distinct architectural strengths and weaknesses.

The MLP model (Table 3) demonstrated relatively stable performance, even without augmentation on L1 data (F1 = 0.85), and saw the smallest absolute improvement from augmentation. This suggests that the carefully engineered statistical and spectral features provide a robust, albeit limited, representation that is somewhat invariant to load changes. However, its performance ceiling appears lower than that of the other models.

The CNN model (Table 4) was the most sensitive to the training data distribution. Without augmentation, its performance on high-load data was poor (F1 = 0.31), likely because the structural patterns in the GAF images for L3 were completely unfamiliar to the network trained only on L2. However, with augmentation, the CNN achieved the highest single score of 0.98 on L1 data. This indicates that CNNs possess a high capacity for learning discriminative features from images, but this capacity is fully unlocked only when provided with a sufficiently diverse and representative training set.

The Hybrid CNN-MLP model (Table 5) achieved the most balanced and highest overall performance when leveraging augmented data. This synergy can be interpreted as follows: the MLP branch provides a “generalizing” influence with its pre-defined, physically grounded features, guiding the model towards robust decision boundaries. Simultaneously, the CNN branch acts as a “specialist,” extracting complementary, high-dimensional spatial patterns from the GAF images that may be missed by the fixed feature set [24]. The fusion layer effectively integrates these two information streams, creating a more comprehensive and resilient feature representation. This result aligns with the growing consensus on the benefits of multi-modal learning in fault diagnosis [23,25].

It is worth noting that our physics-guided data-level approach offers a complementary strategy to model-centric methods for improving generalization, such as those designed for complex scenarios like cross-domain or open-set diagnosis [52,53]. While these advanced techniques employ sophisticated architectures to extract domain-invariant features, our method addresses the fundamental challenge of data scarcity directly by generating physically plausible variations in operational conditions. This makes our solution particularly valuable in industrial settings with limited data sources and where computational resources and model interpretability are key concerns.

4.3. Limitations and Future Work

The conducted experiment also revealed the comparative limitations of each approach. The MLP, reliant on features, demonstrated stability but reached an accuracy ceiling (F1 = 0.88), falling short of the CNN’s ability to extract complex patterns from images. The CNN showed high effectiveness on familiar regimes but proved to be extremely sensitive to data distribution shifts, leading to a sharp drop in performance (F1 = 0.31) on the unseen load L3. The hybrid model, while delivering the best result, does so at the cost of increased architectural complexity and computational load, which could be critical for systems operating under strict real-time constraints.

Beyond architectural limitations, some methodological constraints should be acknowledged. The augmentation primarily addresses frequency shifts in fault harmonics but does not perfectly replicate amplitude variations, as seen in Figure 6. The amplitude of fault components is also influenced by load and other factors [9]; incorporating this relationship could further enhance the physical fidelity of the synthetic data.

For industrial deployment, computational efficiency and model lightweight are critical parameters. The hybrid approach proposed in this work demonstrates a reasonable balance between accuracy and complexity. Unlike more intricate architectures specifically designed for extreme optimization in continuous learning or virtual domain scenarios [54,55], our solution offers a less computationally expensive methodology based on physical data augmentation. This approach enhances model reliability without radically increasing its architectural complexity, making it a practical choice for deployment in monitoring systems with standard computational resources.

Regarding generalization, this study primarily addresses the challenge of data scarcity within a single machine under varying operating conditions. Our physics-guided augmentation is a foundational step that enhances model robustness to load variations. However, we recognize that real-world industrial value further depends on a model’s ability to generalize across different machines (cross-machine diagnosis) and to safely handle previously unseen fault types (open-set recognition), especially under the class imbalance common in real industrial data. These complex scenarios, which involve simultaneous domain shift and class shift, represent the next frontier in diagnostic model development. Promising pathways to address these challenges include meta-learning frameworks designed for imbalanced open-set generalization [56] and advanced domain adaptation techniques. Extending our physics-based data generation approach to create diverse, multi-machine synthetic datasets could serve as a powerful foundation for training such advanced generalization models in the future.

Finally, the success of the physics-guided approach underscores a critical point: for industrial diagnostics where data is scarce and operational conditions vary, incorporating domain knowledge into the data generation process is a powerful strategy. It moves beyond simply expanding dataset size to strategically enriching it with physically meaningful variations. This methodology is not limited to broken rotor bars or current signals; it could be adapted to other fault types (e.g., bearing faults, eccentricity) and systems where fault characteristics shift predictably with operational parameters.

5. Conclusions

This study has presented a comprehensive investigation of a physics-guided spectral augmentation method for diagnosing broken rotor bars in induction motors under variable load conditions. The method operates by simulating changes in motor slip through targeted modifications of the spectral regions containing the rotor fault harmonics. Its efficacy was rigorously evaluated across multiple load scenarios, utilizing a suite of classifier architectures: a Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN), and a hybrid CNN-MLP model.

The experimental results demonstrate a substantial improvement in classification quality with the application of data augmentation across all investigated cases. An increase in accuracy was observed both for the Multilayer Perceptron processing statistical features in the time and spectral domains, and for the Convolutional Neural Network analyzing GAF images. Each approach exhibits distinct characteristics: the MLP model demonstrates stable performance across different loads, achieving a maximum average F1-score of 0.88. The CNN architecture shows higher effectiveness under low load conditions, where it reaches an F1-score of 0.98, while being less performant under high load.

The highest accuracy was achieved by the hybrid CNN-MLP architecture, which combines the advantages of both approaches: the ability of CNN to extract structural patterns in images and the capacity of MLP to process numerical features. This approach achieved the maximum classification accuracy and the largest absolute gain in F1-score when using augmentation, confirming the synergistic effect of jointly utilizing heterogeneous data representations.

This research has confirmed the effectiveness of the physically grounded data augmentation method as a tool for mitigating the limitations of small experimental datasets for various model architectures and equipment operating regimes. The highest results were demonstrated by hybrid architectures, indicating the promise of their application in industrial diagnostics of induction motors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and V.E.; methodology, O.I. and V.E.; software, D.G.; validation, D.G., V.E. and O.I.; formal analysis, O.I.; investigation, D.G.; resources, A.S.; data curation, V.E.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G.; writing—review and editing, V.E. and O.I.; visualization, D.G.; supervision, O.I.; project administration, A.S.; funding acquisition, O.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation No. 25-29-00633, https://rscf.ru/en/project/25-29-00633/ accessed on 15 November 2025.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Skowron, M.; Orlowska-Kowalska, T.; Wolkiewicz, M.; Kowalski, C.T. Convolutional Neural Network-Based Stator Current Data-Driven Incipient Stator Fault Diagnosis of Inverter-Fed Induction Motor. Energies 2020, 13, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, N.S.; Memane, N.P.; Akuru, U.B. Performance and Safety Improvement of Induction Motors Based on Testing and Evaluation Standards. CES Trans. Electr. Mach. Syst. 2024, 8, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzimov, S.; Jiangzhong, Z.; Latipov, S.; Shahzad, M.A. Fault Detection in Induction Motors: Recent Advances and Future Prospects. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Problems of Informatics, Electronics and Radio Engineering (PIERE), Novosibirsk, Russian Federation, 15–17 November 2024; pp. 1420–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisedzi, L.P.; Muteba, M. Detection of Broken Rotor Bars in Cage Induction Motors Using Machine Learning Methods. Sensors 2023, 23, 9079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundogdu, T.; Suli, S. Role of End-Ring Configuration in Shaping IE4 Induction Motor Performance. CES Trans. Electr. Mach. Syst. 2024, 8, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhao, W.; Hu, Y.; Ji, J.; Tao, T. Review of Fault-Tolerant Control for Motor Inverter Failure with Operational Quality Considered. CES Trans. Electr. Mach. Syst. 2024, 8, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.K.; Al Kazzaz, S.A.S. Induction Machine Drive Condition Monitoring and Diagnostic Research—A Survey. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2003, 64, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.; Panagiotou, P.A.; Antonino-Daviu, J.A.; Gyftakis, K.N. Efficiency Assessment of Induction Motors Operating Under Different Faulty Conditions. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2019, 66, 8072–8081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voldek, A.I. Elektricheskie Mashiny [Electrical Machines], 3rd ed.; Energiia: Leningrad, Russia, 1978; 832 p. [Google Scholar]

- Kliman, G.B.; Stein, J. Methods of Motor Current Signature Analysis. Electr. Mach. Power Syst. 1992, 20, 463–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Qiu, R.; Liu, Z. Characteristics Analysis and Measurement of Inverter-Fed Induction Motors for Stator and Rotor Fault Detection. Energies 2019, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henao, H.; Razik, H.; Capolino, G.-A. Analytical Approach of the Stator Current Frequency Harmonics Computation for Detection of Induction Machine Rotor Faults. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2005, 41, 801–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotou, P.A.; Mayo-Maldonado, J.C.; Arvanitakis, I.; Escobar, G.; Antonino-Daviu, J.A.; Gyftakis, K.N. A Novel Method for Rotor Fault Diagnostics in Induction Motors Using Harmonic Isolation. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 14th International Symposium on Diagnostics for Electrical Machines, Power Electronics and Drives (SDEMPED), Crete, Greece, 28 August 2023; pp. 265–271. [Google Scholar]

- Sobczyk, T.J.; Maciolek, W. Diagnostics of Rotor-Cage Faults Supported by Effects Due to Higher Mmf Harmonics. In Proceedings of the 2003 IEEE Bologna Power Tech Conference Proceedings, Bologna, Italy, 23–26 June 2003; Volume 2, pp. 288–292. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.B.; Stone, G.C.; Antonino-Daviu, J.; Gyftakis, K.N.; Strangas, E.G.; Maussion, P.; Platero, C.A. Condition Monitoring of Industrial Electric Machines: State of the Art and Future Challenges. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2020, 14, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Machlev, R.; Wang, Q.; Belikov, J.; Levron, Y.; Baimel, D. A Public Data-Set for Synchronous Motor Electrical Faults Diagnosis with CNN and LSTM Reference Classifiers. Energy AI 2023, 14, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evangeline, S.I.; Darwin, S.; Raj, E.F.I. A Deep Residual Neural Network Model for Synchronous Motor Fault Diagnostics. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 160, 111683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessam, B.; Menacer, A.; Boumehraz, M.; Cherif, H. Detection of Broken Rotor Bar Faults in Induction Motor at Low Load Using Neural Network. ISA Trans. 2016, 64, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrera-Llanga, K.; Burriel-Valencia, J.; Sapena-Bañó, Á.; Martínez-Román, J. A Comparative Analysis of Deep Learning Convolutional Neural Network Architectures for Fault Diagnosis of Broken Rotor Bars in Induction Motors. Sensors 2023, 23, 8196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, T.-H.; Lee, J.-H.; Choi, B.-K. CNN-Based Fault Classification in Induction Motors Using Feature Vector Images of Symmetrical Components. Electronics 2025, 14, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtierra-Rodriguez, M.; Rivera-Guillen, J.R.; Basurto-Hurtado, J.A.; De-Santiago-Perez, J.J.; Granados-Lieberman, D.; Amezquita-Sanchez, J.P. Convolutional Neural Network and Motor Current Signature Analysis during the Transient State for Detection of Broken Rotor Bars in Induction Motors. Sensors 2020, 20, 3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsueh, Y.-M.; Ittangihal, V.R.; Wu, W.-B.; Chang, H.-C.; Kuo, C.-C. Fault Diagnosis System for Induction Motors by CNN Using Empirical Wavelet Transform. Symmetry 2019, 11, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wen, S.; Sheng, S.; Ma, H. Multi-Signal Induction Motor Broken Rotor Bar Detection Based on Merged Convolutional Neural Network. Actuators 2025, 14, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinitsin, V.; Ibryaeva, O.; Sakovskaya, V.; Eremeeva, V. Intelligent Bearing Fault Diagnosis Method Combining Mixed Input and Hybrid CNN-MLP Model. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 180, 109454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Liu, J.; Zhao, R.; Xu, Y.; Huo, T. A New Dual-Channel Convolutional Neural Network and Its Application in Rolling Bearing Fault Diagnosis. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 096130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, S.; Feng, Y.; Gryllias, K.; Gu, F.; Pecht, M. Small Data Challenges for Intelligent Prognostics and Health Management: A Review. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2024, 57, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, Y.M.; Hernández-Callejo, L.; Duque-Pérez, O.; Alonso-Gómez, V. Diagnosis of Broken Bars in Wind Turbine Squirrel Cage Induction Generator: Approach Based on Current Signal and Generative Adversarial Networks. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, J.; Li, F.; Pan, T.; He, S. A Small Sample Focused Intelligent Fault Diagnosis Scheme of Machines via Multimodules Learning With Gradient Penalized Generative Adversarial Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 68, 10130–10141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z.; Li, L.; Xu, T. Data Augmentation for Time-Series Classification: An Extensive Empirical Study and Comprehensive Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.10060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Ding, Q.; Sun, J.-Q. Intelligent Rotating Machinery Fault Diagnosis Based on Deep Learning Using Data Augmentation. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K.; Kim, H.; Chae, M.; Oh, H.J.; Yoon, H.; Youn, B.D. Self-Supervised Feature Learning for Motor Fault Diagnosis under Various Torque Conditions. Knowl. -Based Syst. 2024, 288, 111465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shestakov, A.L.; Galyshev, D.V.; Eremeeva, V.A.; Ibryaeva, O.L. Broken Rotor Bar Fault Diagnosis Using Spectrum Distortion for Data Augmentation. In Proceedings of the 2025 27th International Conference on Digital Signal Processing and its Applications (DSPA), Moscow, Russia, 26 March 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bejaoui, I.; Bruneo, D.; Xibilia, M.G. A Data-Driven Prognostics Technique and RUL Prediction of Rotating Machines Using an Exponential Degradation Model. In Proceedings of the 2020 7th International Conference on Control, Decision and Information Technologies (CoDIT), Prague, Czech Republic, 29 June–2 July 2020; pp. 703–708. [Google Scholar]

- Susilo, D.D.; Widodo, A.; Prahasto, T.; Nizam, M. Remaining Useful Life Estimation of the Motor Shaft Based on Feature Importance and State-Space Model. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference and Exhibition on Sustainable Energy and Advanced Materials, Surakarta, Indonesia, 16–17 October 2019; pp. 675–688. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; He, Y.; Chen, X.; Pu, X. Optimization of Dilated Convolution Networks with Application in Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Induction Motors. Measurement 2022, 200, 111588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farajzadeh-Zanjani, M.; Razavi-Far, R.; Saif, M. A Critical Study on the Importance of Feature Extraction and Selection for Diagnosing Bearing Defects. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 61st International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Windsor, ON, Canada, 5–8 August 2018; pp. 803–808. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Liang, Q.; Hancock, J.T.; Khoshgoftaar, T.M. Feature Selection Strategies: A Comparative Analysis of SHAP-Value and Importance-Based Methods. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barandas, M.; Folgado, D.; Fernandes, L.; Santos, S.; Abreu, M.; Bota, P.; Liu, H.; Schultz, T.; Gamboa, H. TSFEL: Time Series Feature Extraction Library. SoftwareX 2020, 11, 100456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, D.; Liu, Z.; Gao, Q.; Yao, J.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Z. Few-Shot Fault Diagnosis of EHA Based on MTF-ResNet-MA and Dual-Attribute Adaptive Decision-Level Fusion. Measurement 2025, 247, 116787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Oates, T. Imaging time-series to improve classification and imputation. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Buenos Aires, Argentina, 25–31 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Zheng, L.; Zheng, G.; Wang, J. Rolling Bearing Fault Diagnosis Method Based on GAF-MTF and Deep Residual Network. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Sensing, Diagnostics, Prognostics, and Control (SDPC), Shijiazhuang, China, 26–28 July 2024; pp. 106–111. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay, S.; Kar, I.; Ralte, Z. Robust Fault Diagnostics of Industrial Motors: The Signal-to-Image Approaches for Sensor Data Using Multi-Task Transformers with Diverse Attention Mechanism. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Control, Instrumentation, Energy & Communication (CIEC), Kolkata, India, 25–27 January 2024; pp. 129–134. [Google Scholar]

- Eckmann, J.-P.; Kamphorst, S.O.; Ruelle, D. Recurrence Plots of Dynamical Systems. Europhys. Lett. 1987, 4, 973–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarek, A.; Sameh, M. Improved Deep-Learning Rotor Fault Diagnosis Based on Multi Vibration Sensors and Recurrence Plots. J. Vib. Control 2025, 31, 1874–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.; Yun, S.-H.; Lim, Y.-S.; Cheong, S.; Bae, J.; Park, Y.-H. Fault Diagnosis of Inter-Turn Short Circuit in Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors with Current Signal Imaging and Semi-Supervised Learning. In Proceedings of the IECON 2022—48th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Brussels, Belgium, 17–20 October 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, G.R.; Michau, G.; Ducoffe, M.; Gupta, J.S.; Fink, O. Temporal Signals to Images: Monitoring the Condition of Industrial Assets with Deep Learning Image Processing Algorithms. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O J. Risk Reliab. 2022, 236, 617–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Pang, X.; Li, F.; Lu, K.; Hu, S. Gearbox Fault Diagnosis Method Based on Improved Semi-Supervised MTDL and GAF. Meas. Control 2024, 57, 1181–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Kim, H.; Suh, C.; Chae, M.; Yoon, H.; Youn, B.D. A Health Image for Deep Learning-Based Fault Diagnosis of a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor under Variable Operating Conditions: Instantaneous Current Residual Map. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 226, 108715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejazi, S. Improving Induction Motor Fault Classification Accuracy Through Enhanced Multimodal Preprocessing, Artificial image Synthesis, Deep Learning and Load-Adaptive Graph-Based Methods. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bellini, A.; Filippetti, F.; Tassoni, C.; Capolino, G.-A. Advances in Diagnostic Techniques for Induction Machines. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2008, 55, 4109–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Rudin, C.; Shaposhnik, Y. Understanding How Dimension Reduction Tools Work: An Empirical Approach to Deciphering T-SNE, UMAP, TriMap, and PaCMAP for Data Visualization. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 22, 1–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Jie, H.; Yang, J.; Gao, T.; Zhao, Z.; Chang, Y.; See, K.Y. A Multi-Source Domain Feature-Decision Dual Fusion Adversarial Transfer Network for Cross-Domain Anti-Noise Mechanical Fault Diagnosis in Sustainable City. Inf. Fusion 2025, 115, 102739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Yang, J.; Jie, H.; Gao, T.; Zhao, Z. Addressing Unknown Faults Diagnosis of Transport Ship Propellers System Based on Adaptive Evolutionary Reconstruction Metric Network. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65, 103287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, B. Continuous Evolution Learning: A Lightweight Expansion-Based Continuous Learning Method for Train Transmission Systems Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 8270–8281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Jie, H.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Gao, R.; Suganthan, P.N. A Virtual Domain-Driven Semi-Supervised Hyperbolic Metric Network With Domain-Class Adversarial Decoupling for Aircraft Engine Intershaft Bearings Fault Diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 7950–7963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Shu, Z.; Yang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Jie, H.; Chang, Y.; Jiang, S.; See, K.Y. Learning to Imbalanced Open Set Generalize: A Meta-Learning Framework for Enhanced Mechanical Diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2025, 55, 1464–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).