Abstract

In configuration design, the task is to compose a system out of a set of predefined, modu-lar building blocks assembled by defined interfaces. Product configuration systems, both with or without integration of geometric models, implement reasoning techniques to model and explore the resulting solution spaces. Among others, the formulation of constraint satisfaction problems (CSP) is state of the art and the informational background in many proprietary configuration engine software packages. Basically, configuration design tasks can also be implemented in modern computer aided design (CAD) systems as these contain different techniques for knowledge-based product modeling but literature reports only little about detailed application examples, best practices or training materials. This article aims at bridging this gap and presents a step-by-step implementation guide for CSP-based CAD configurators for combinatorial designs with the example of Autodesk Inventor.

1. Introduction

The design of variant-rich, configurable products has not just been a topic since the rise of Mass Customization during the 1990s [1,2]. In configuration design, the task is to compose a system out of a set of predefined, modular building blocks assembled by defined interfaces [3,4]. Depending on count and quality of the interfaces, a small number of building blocks already leads to huge solution spaces, i.e., the set of all feasible configurations. Taking the example of Durhuus and Eilers [5], six LEGO bricks in the size 2 to 4 span a solution space of 915,103,765 possible configurations when the only restriction is that all blocks need somehow to be connected to at least another one in the usual rectangular grid. Assuming that an average designer would need around 5 min to assemble the six bricks in a computer aided design (CAD) system, derive a technical drawing with bill-of-materials and check-in the data into a product data management system, the manual documentation of all configurations would take approx. 8705 years, working 24/7. In automotive engineering, the manifold of solution spaces is even magnitudes larger [6].

Automating such (routine) design tasks is one aim of knowledge-based engineering, with product configurators as an instance for its application [7,8]. One of the first documented product configuration systems dates back to the 1980s, which is McDermott’s R1/XCON rule-based configurer [9]. While this system in its final version used thousands of production rules as inference engine to get from requirements to the needed product variant, other approaches rely on model-based reasoning techniques, like the formulation of constraint satisfaction problems (CSP) [10,11]. In brief, a CSP consists of a set of finite domains as containers for variables and their possible parameter values as well as a set of constraints that are links between the domains and determine which combinations of values of the single variables are allowed [12]. Compared to rule-based systems, the CSP approach usually leads to better performance, reduced maintenance effort and higher implementation efficiency [13].

There exists a multitude of proprietary software packages to integrate constraint-based configuration and CAD [14,15]. However, many of today’s CAD systems offer plenty of functionalities already in their out of the box version to implement knowledge-based designs and configurators [16]. These functionalities include, among others, design rules, mathematical and logical constraints between parameters and design features, parameter control via spreadsheets and script languages, as well as of course the application programming interface (API) [17,18,19]. A CAD-based design automation system using these functionalities can perform the above task of assembling the six LEGO bricks in less than two days on today’s desktop computers. Nonetheless, the implementation of CSP-based configuration designs needs a level of abstraction since the initial design problem needs to be transformed into a configuration problem [20]. Afterwards, the information system needs to be designed accordingly to this.

Engineering literature reports only little about detailed application examples, best practices or training materials related to this topic. Existing workbooks usually are related to expert system shells from the 1990s, e.g., PLAKON [21,22] or the above-mentioned proprietary software packages. In order to foster and promote the possibilities and application of constraint-based configuration and to encourage engineers in using this approach for configurable assemblies, this contribution presents a step-by-step implementation guide for CSPs into combinatorial CAD models. The CAD assembly is set up in the CAD system Autodesk Inventor, the constraint solver is implemented through its API.

The article is structured as follows: In Section 2, the theoretical background of constraint satisfaction problems as a model-based reasoning technique is briefly illustrated, before Section 3 introduces the running example for the configuration design task. Section 4 then presents a specification of the information system to be built. In Section 5, the code for the CSP implementation is developed, including an introduction of new domains and constraints afterwards. The coupling to the CAD model is discussed in Section 6. The final Section 7 concludes the article.

2. Theoretical Background

Basically, inference mechanisms as part of a knowledge-based engineering system can be implemented on the basis of model elements and their relations. Depending on how both are modeled, literature distinguishes logic-based, constraint-based and resource-based approaches [13].

For a logic-based representation of knowledge and reasoning, an object-oriented data structure is used [23]. This consists of the actual objects (so-called individuals), logical structures for aggregating objects (concepts) and binary relationships between individual objects (roles). Objects, in a narrow sense, may be understood as classes, from which arbitrarily many instances can be derived and assigned different values. Additionally, the class concept allows attributes of objects to be inherited from higher hierarchy levels. The reasoning is performed by checking whether a special object is included in a superordinate class [11].

Constraint-based approaches represent, as mentioned in the introduction, constraint networks where a constraint represents the relation between two model elements and has a rule for value assignment [13]. In this way, e.g., physical or engineering contexts can be modeled, e.g., the calculation of a bolted connection. Values applied to the constraint network can then be propagated, which means that the values of all other model elements are calculated on their basis. By nature, it is irrelevant according to which variables the formulas are resolved and which variables are used as inputs [24]. CSPs in this application correspond to a system of equations, constraint propagation to the solution of the system of equations.

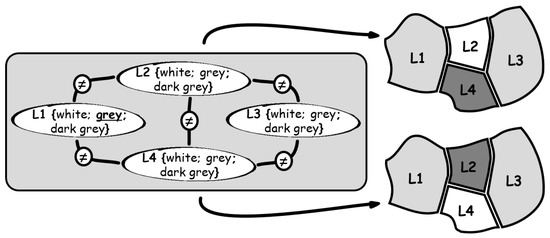

A further very typical task for constraint-based reasoning is the representation of configuration problems. For this, the elements are modeled likewise with their value ranges and relations. An example for this is the so-called map coloring problem [25]. As shown in Figure 1, the single countries are abstracted into domains containing the available colors for the map as values. Inequality constraints are introduced between two neighboring countries, expressing that neighboring countries are to be colored differently [26].

Figure 1.

Map coloring problem (initial value for constraint propagation highlighted in L1).

A constraint solver now has the task of finding solutions for the constraint network that satisfy all constraints. For this purpose, different algorithms are available, e.g., Gener-ate-and-Test, which systematically tests possible parameter combinations. However, this method also calculates predictably erroneous value assignments. In the example of the map in Figure 1, L1 has an initial value grey. The solver then sequentially assigns colors to the other domains and tests the involved constraints. Starting with L2 = white, the constraint between L1 and L2 is satisfied. Proceeding to L3 = white, a constraint is violated, the solution is discarded. The algorithm will then return to the last known state that satisfied all constraints and change the last variable assignment. If L3 is then assigned gray instead of white, the problem can be further processed and solved. This procedure is called backtracking [26].

Since a constraint network can be written as a graph (the domains form the nodes, the constraints the arcs), alternative algorithms exploit graph-theoretic methods to reduce the effective search space by enforcing local consistency. A CSP is considered node-consistent if all unary constraints, which limit the value of a single variable, are satisfied. Arc consistency involves binary constraints between domains. Inconsistent values from the further involved domain are then immediately removed for the search [12]. For the example in Figure 1, this means that the value gray can no longer be available for L2 and L4 because L1 is already occupied by gray as input. Path consistency extends this by not only collapsing one domain but removing pairs of values from a constraint [26]. Continuing the above example with pre-collapsed L2 and L4, gray remains as a single consistent value for L3 and leads automatically to the two solutions depicted on the right of the figure, without testing further configurations.

Resource-based reasoning is a special case of constraint-based reasoning. Here, the relationships between the model elements are represented on the basis of resource consumption and provision functions. The reasoning mechanism then aims at achieving a state of equilibrium. The concept is kept abstract and counts also, e.g., installation space, assembly time or technical interfaces to resources [27].

For use in a design automation system or in constraint-based configuration, such reasoning mechanisms need to be coupled with a product model [20]. Such a product model can be a realized as a simple catalog from which options are chosen by the algorithm. Another implementation aims at the generation of a geometric (CAD) model for visualization or further processing in the sense of design templates [28,29]. Note that model-based reasoning in general is able to include configurable artifacts beside the actual product model. On the one hand, this may be, e.g., the joint configuration of product features and their respecting manufacturing processes [30,31], but also combines product and service configuration in hybrid offerings [32].

3. Modeling Task

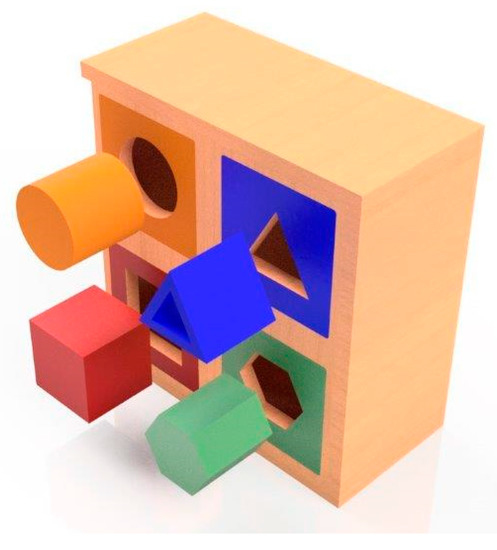

The running example for this article is a configurable toy sorting box for small kids as depicted in Figure 2. The customer first chooses four different slots that are described by article number, shape and color. In a second configuration step, the customer can choose a brick variant for the selected slots, which is described by article number, color, shape and infill (flat, raised, embossed—refer, e.g., to the blue prism bricks in Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Configurable toy sorting box with according brick variants.

For the slots, ten different variants are available. The main restriction is that no equal slots may be chosen. Permutations (red, yellow, green, blue OR red, blue, green, yellow) are to be allowed. Nonetheless, if the customer by incident chooses a predefined template configuration (three out of four connected colors), the last color should automatically be restricted to the missing template slot. Depending on the chosen slot, there may be up to three possible brick variants for the second configuration step.

4. Specification of the Information System

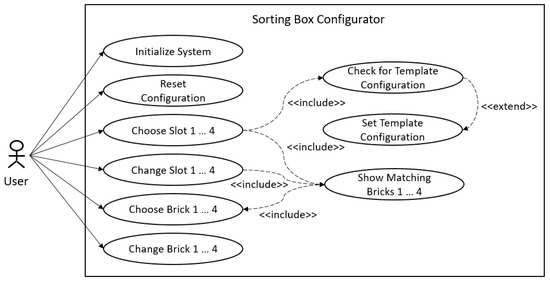

The resulting customer interaction during configuration is depicted in the use case diagram in Figure 3. Besides choosing slots and bricks, the customer should furthermore be able to change or reset a choice or the whole configuration as such at each point of the configuration process. In order to keep the configuration process flexible, it should not matter in which sequence the slots are selected by the user.

Figure 3.

Use case diagram for customer interaction.

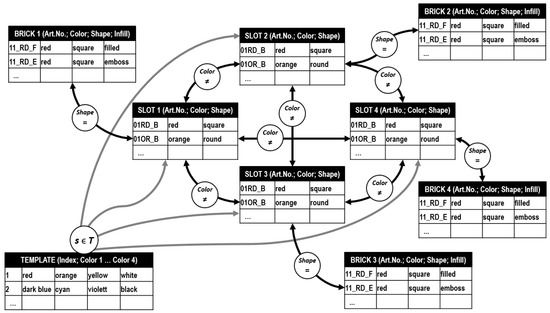

The abstraction of the design problem to a configuration problem results in a first set of four domains SLOT1 … SLOT4 representing the slots with their respective alternatives. A second set of four domains BRICK1 … BRICK4 contains the representation of all brick variants.

As constraints, inequality of SLOT1, SLOT2, SLOT3 and SLOT4 to each other is expressed by bidirectional constraints. The bidirectionality leads to the fact that it later does not matter which value must be set first and which must be propagated afterwards. Additionally, equalities between the slots and the corresponding bricks are introduced. A special feature of the configuration tool is the template definition of four predefined colors. Therefore, an auxiliary domain TEMPLATE is created that contains the template configurations. This constraint is only to be propagated if three slot domains, independently which of them, have an assigned value, otherwise the constraint is relaxed. The resulting constraint network is depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Constraint network for the sorting box configuration problem.

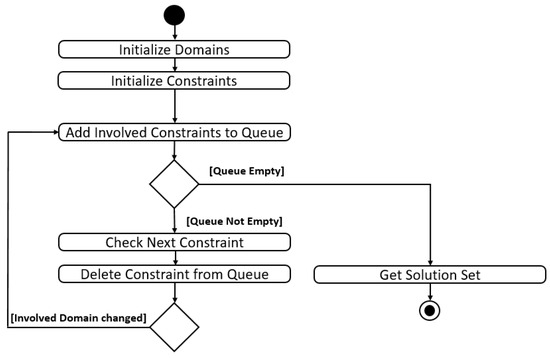

In order to avoid hardcoding of domains, variables and constraints, domain and constraint lists should be stored externally and so be easily updateable and extendable. After starting the configuration tool, the first step is that domain and constraint lists are loaded from this repository and the constraint network is established automatically in the blackboard of the configuration tool (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Activity diagram for constraint handling.

The system then waits for user inputs and adds all involved constraints linked to the changed domain to a queue. As long as the queue is not empty, the solver sequentially propagates and deletes the next constraint in the queue. Afterwards, in order to apply local consistency, the system checks whether neighboring domains have been affected. If so, again the involved constraints are added to the end of the queue. After the queue has been completely processed, the solution set is output.

5. Building the CSP

The implementation is designed for Autodesk Inventor Professional as representative for parametric CAD systems with knowledge-based product modeling and a Visual Basic for Applications (VBA) API, which is commonly available as basic API language in many CAD systems. Although this language has many deficiencies and more similarities to scripting automation, this origin in macros still keeps it widespread in the mechanical engineering domain and practically relevant. As Inventor additionally offers the possibility to integrate and embed MS Excel spreadsheets into the CAD model, Excel was chosen as the repository for domain and constraint lists. Other spreadsheet applications are not supported in this context. So, the CSP-based configurator is implemented as VBA macro with its own user interface in order to control both Excel and Inventor for the later CAD assembly.

As a domain can be abstracted as a list of variables and their values, dictionaries are a feasible representation as they offer some advantages over, e.g., array lists: First, all dictionary properties are writable and retrievable (including the key values) and can handle nearly every type of key except arrays. Second, dictionary methods offer the possibility to check if a key value already exists. Finally, although slower in initial creation, dictionaries are significantly faster in processing than array lists. In order to use dictionaries, the MS scripting runtime within VBA must be activated.

The code for the example is available in the appendix of this article and additionally via https://doi.org/10.25835/6wdfdp03 (last accessed on 4 September 2022). The link contains the Autodesk Inventor 2020 and Excel files as well as separate VBA files (form, basic and class files) with the code for the sorting box with four slots and four bricks. The data set is reduced to an empty assembly and the macro. No part files or geometry is included. So, the macro in this form should also work as it is with other CAD systems which use VBA as scripting language by importing the corresponding VBA files into the macro editor.

5.1. Domain and Constraint Lists

Beside the VBA form for the configuration system, the user interface also contains the repository for the domain and constraint lists. Regarding the two domains for slots and bricks, Figure 6 shows the structure in the Excel spreadsheet. Each domain is situated on its own workbook containing all describing properties like Article Number, Color, Shape and, in the case of the bricks, additionally the Infill as columns with headlines.

Figure 6.

Spreadsheet definition for slot (left) and brick (right) domain.

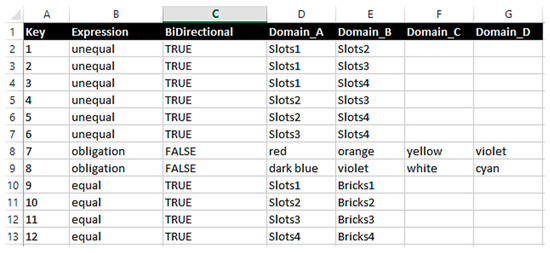

As can be seen from the constraint network, the constraint list has to store equality, inequality and the obligatory assignment of the fourth color from a template. This is coded as Expression as depicted in Figure 7. Additionally, the requirement of a flexible configuration process and local consistency leads to the distinction of both unary and binary constraints. In order to maintain a uniform declaration, a single constraint can include up to four arguments. Two are needed for equality and inequality, i.e., the two domains that are linked by the constraint. Four (the colors of the template) are needed for handling the obligatory assignment.

Figure 7.

Spreadsheet constraint definition.

5.2. Creating Domains and the Constraint List

Before the actual handling of the input data can take place, the initial variable declarations need to be done in VBA (Appendix A, row 1 to 21). Beside the dictionaries for the eight domains, two additional dictionaries dict_SlotsORI (for original) and dict_BricksORI are declared. These domain masters are intended as reference objects to be written in the blackboard of the configuration system. E.g., if a domain needs to be reset when the user changes his or her selection, the domain master is copied in the respecting domain and all constraints are to be regenerated without reobtaining data from the spreadsheet.

Furthermore, the dictionaries dict_ConList and dict_ConQue are declared for constraint handling. The first is meant as a reference list containing all constraints, the second is the actual queue. Finally, a global counter is declared, which is needed for the template constraint and global strings as the internal working memory for assigned domain values.

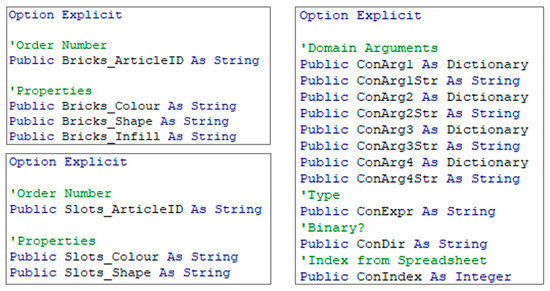

Additionally, as part of the variable declaration, three public class modules iComponent_Bricks, iComponent_Slots and iConstraint are introduced as follows in Figure 8. The first two define the domains and their properties, which are translated to the columns of the dictionaries later. The last class module is the generalized constraint variable. The dictionaries ConArg1 … ConArg4 represent domains that are connected to a constraint, the strings formalize value assignments. This is, e.g., necessary for the template configurations where these arguments contain the four colors. Additionally, the string ConExpr contains the type of the constraint, ConDir, whether it is unary or binary.

Figure 8.

Declaration of public classes.

The subroutine for reading the inventory and creating the blackboard is shown in Appendix A, row 62 to 76. Beside the path to the spreadsheet, it basically contains three functions that address the single workbooks. Note that the path to the repository in row 62 needs to be adjusted to the path where the repository is locally saved.

The generation of the domains can be found in Appendix A, row 79 to 109 for the slots and row 112 to 143 for the bricks. In the first part of both routines, the domain master is created. Basically, it adds each row from row two on (first row is the column headline) of the spreadsheet to the dictionary. Thereby, ArticleID is a temporary variable which contains the key for the dictionary. Reading the spreadsheet ends when an empty cell in the first column of the spreadsheet is reached. After the reference is created, it is distributed to the four respecting domains as the initial solution set.

Populating the constraint reference list works similar, as shown in Appendix A, row 145 to 271. The key is realized as a counter. In order to couple domains with equality and inequality constraints (Appendix A, row 154 to 249), the involved domains need to be declared as arguments. As VBA does not allow to compose variable names out of, e.g., a combination of strings and numeric values at runtime, the strings obtained from the spreadsheet once need to be related to the dictionaries. Therefore, the select case expressions contain the corresponding assignments for the constraint arguments. Additionally to the dictionaries, the arguments are also stored as strings for further processing. If the constraint is binary, a second constraint with opposite arguments is created.

If the spreadsheet contains a constraint with the expression Obligation, the four arguments of the corresponding entry in the constraint list are populated with the four colors as shown in Appendix A, row 251 to 271.

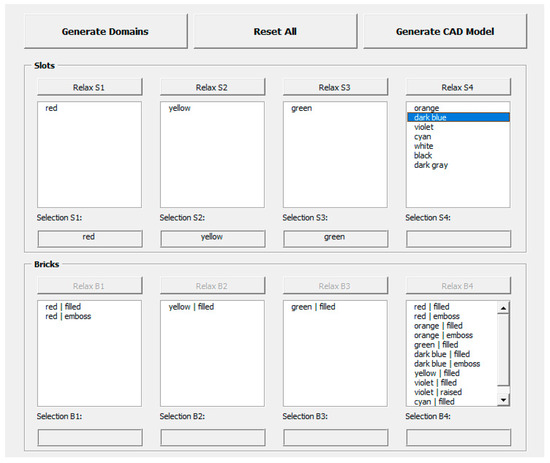

5.3. User Interface

Following the use case diagram from Figure 3, the user form needs to contain control elements for system initialization (command button Generate Domains which starts Sub read_inventory), resetting the whole configuration process (command button Reset All which clears all domains and outputs), as well as choosing and resetting of slots and bricks and generating the CAD model (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

User form for sorting box configuration.

Primary user interaction elements are list boxes. After initialization, the configuration system writes the domain content as items into the respective list box. The user then can double click on an item to make his or her selection which is written into a label (e.g., red, yellow and green in Figure 9) and the remaining list boxes are updated after constraint handling. For each selection, a command button relax is implemented which resets just the according domain and updates the others after constraint handling. The VBA code for the user form including the naming of control elements is documented in Appendix B.

5.4. Constraint Handling

5.4.1. Queueing

After initialization, the queue is at first empty. If now the user chooses a slot by double clicking on an entry in a list box, the code in Appendix B, row 45 to 69, first establishes node consistency as it processes the unary constraint for collapsing the respecting domain SLOT1. Afterwards, it increases the counter for the selected domains by one which is relevant for the queueing of the obligatory assignments.

Afterwards, the actual queueing takes place as the configuration system scans through the constraint reference list from the blackboard and adds either all equality/inequality constraints to the queue where the involved domain is the first argument (source) or it adds the obligation constraints if three of four slots have been selected by the user. The code for the other list box inputs is similar.

5.4.2. Solver and Output of the Solution Set

The constraint solver itself is mainly organized within a while loop that is processed until the queue is empty (Appendix A, row 323 to 369). Therefore, the first constraint from the queue is taken and read out in a temporary variable set. Afterwards, the constraint is deleted from the queue and, depending on the expression of the constraint, the arguments are used to call the according functions.

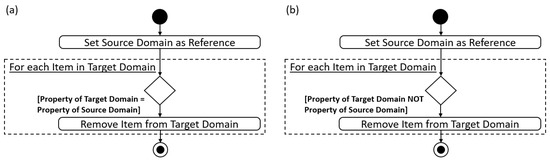

The function Del_Equal_Slots (Appendix A, row 484 to 498) eliminates values that are equal to those of a source domain and is used to process the inequality constraints. The function Bricks_to_Slots (Appendix A, row 501 to 516) processes the equality constraints as it eliminates all values that are unequal to those of a source domain (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Activity diagram for inequality (a) and equality (b) constraint handling.

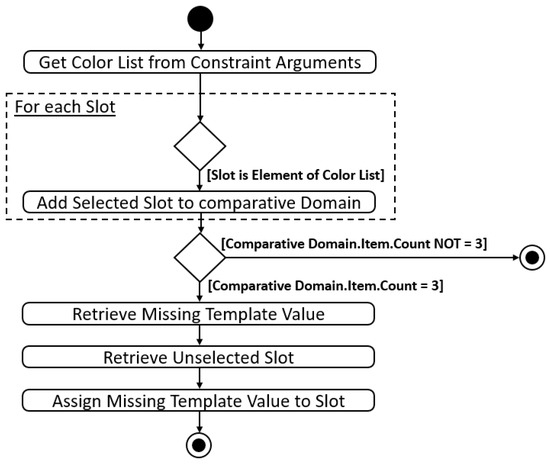

Handling the obligatory assignments is a bit more complicated since it should not matter which order or domain assignment the three chosen are. Figure 11 depicts the structure of the corresponding code (Appendix A, row 518 to 625).

Figure 11.

Activity diagram for handling the obligatory assignment of fourth template slot.

The final output of the solution set is then organized as an update of the list boxes after the queue has been processed (Appendix A, row 274 to 320).

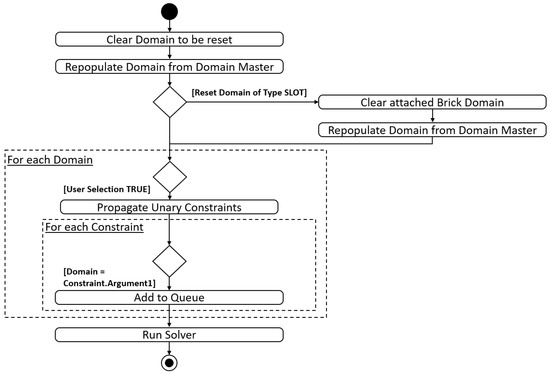

5.5. Resetting a Selection

In order to reset an already made choice, Figure 12 describes the activities of the configuration system. At first, the domain to be reset is cleared and repopulated from the domain master. If the reset domain is of type slots, the corresponding brick domain is reset as well. In the next step, all domains that have already been processed by the user and that have a selection are reevaluated by propagating all unary constraints assigned to it. In this way, the according solution set is extended by the selection which has been reset. Afterwards, each constraint from the constraint list is evaluated if the actual domain is the source, i.e., first argument. If so, the constraint is added to the queue. After all domains have been reevaluated, the constraint solver is activated and the reset is completed. The corresponding code is shown in Appendix A, row 372 to 468.

Figure 12.

Activity diagram for relaxing constraints and update.

5.6. Extending the Example from 8 to 10 Domains

In order to show a typical maintenance task beside the adaption of the domain content, the following steps describe the extension of the existing CSP with each a fifth slot and brick domain.

At first, the user interface in userform1 is extended by the relevant control elements which are copied and renamed according to the existing naming convention (e.g., into lbx_slots5).

Regarding the code in the module main (Appendix A), the first step is to add the corresponding new variable declarations for dict_Slots5 and dict_Bricks5 according to row 5 and 8. Other extensions involve:

- Sub reset: New domains and control elements integrated according to Appendix A, row 26, 31, 40, 44, 48 and 52.

- Sub generate domains: New loop according to Appendix A, row 96 to 98 and row 130 to 132.

- Sub get_constraints: New translations like in Appendix A, row 160/161, 168/169, 180/181, 188/189, 208/209, 214/215, 227/228, 235/236.

- Sub update_listboxes: Introduction of slots5 and bricks5 according to Appendix A, row 277–282 and 300–304.

- Sub constraint_relax: Introduction of slots5 and bricks5 according to Appendix A, row 375–387 and 426–434.

Afterwards, the new control elements need to be equipped with their event handlers:

- cmd_relax_1_5: Code added according to Appendix B, row 8–16.

- lbx_slots5_doubleclick: Code added according to Appendix B, row 45–69.

At last, the constraint list in the spreadsheet needs to be extended with four inequality constraints linking each SLOT1, SLOT2, SLOT3 and SLOT4 to SLOT5 as well as an equality constraint linking SLOT5 and BRICKS5.

The above changes do not include the extension of the obligatory assignment. Here, the spreadsheet and the constraint handling need to be added by a fifth domain argument DOMAIN_E.

6. Addressing the CAD Assembly

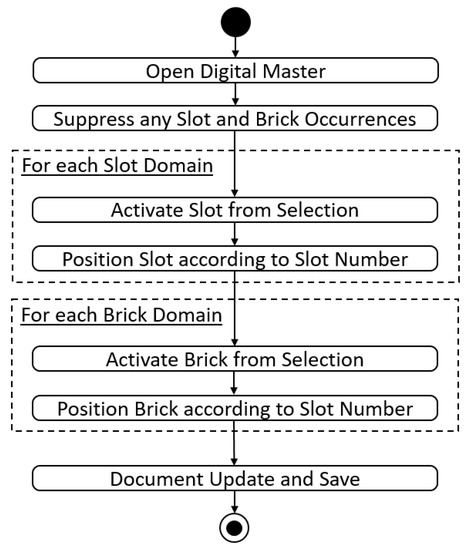

Basically, two different options for the integration of the CAD model are available. On the one hand, following the principle of the digital master, an assembly document contains all possible part and feature occurrences that are either activated or suppressed according to the configured product. On the other hand, a model or draft generator starts with an empty assembly document and adds all parts and features from the configured product to it. An advantage of the former is that the assembly is created completely in advance, i.e., including all positioning dependencies or geometric constraints between components. Accordingly, the advantage of the latter is that there is no need for an assembly to be predefined and engineered in advance, but the positioning of each part needs to be automated instead. In the case of the sorting box, the configuration system merges both principles since there are no duplicate selections.

When the user approves his or her choice and initializes the generation of the CAD model, the configuration system opens the digital master for the sorting box assembly, as shown in Figure 13. Afterwards, any activated parts are suppressed to assure an explicit initial state. The system then processes each slot and transmits the according user selection to the CAD model where the corresponding slot part is activated. Afterwards, this part is positioned in the fixed grid according to its position (SLOT1 is upper left, SLOT2 upper right, etc.). This avoids including redundant slot parts at each position. After the slots have been activated and positioned, the configuration system processes the bricks accordingly (Figure 14).

Figure 13.

Activity diagram for CAD model update.

Figure 14.

Configured sorting box.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Focusing on the above configuration problem, the core of the example, the configuration of the four slots mirrors exactly the map coloring problem which has been extended by additional related choices and the obligatory assignment of an option depending on selections made by the user. Thus, the example of the sorting box is a placeholder for many configurable assemblies and products. Taking online car configurators, the functionalities of mandatory choices, configuration interdictions and the realization of templates or lines of equipment are similar functions. The search strategy for the solution is kept simple in this example by enforcing local consistency, without further examining the time complexity of the solution algorithm. User input or a modification of a domain leads to adding the corresponding constraints to the queue without further nesting or querying. In this case, there is no need for backtracking. Further constraints could be hierarchical constraints or additional classifying criteria, e.g., if two light colors are chosen, only two dark colors may be added, which correspond widely to the obligatory assignments.

Due to the separation of knowledge base, i.e., the spreadsheet, inference engine, i.e., the API code, and the CAD model, a more or less linear control flow is realized. A function which has not been included is math constraints since these can also be expressed directly in the geometric CAD model by, e.g., relating parameters by calculations. In this context, a more complex control flow might integrate reobtaining parameter values from the CAD model, e.g., values of dimensions, and feed them back into the CSP. An open question is if modeling complex assemblies like known from plant engineering, which contain several hundred domains, is adequate with this kind of implementation and the search strategy or if the performance will suffer compared to configurators based on proprietary software packages.

A deficiency of the presented example is the fact that VBA does not allow generating variables or code at runtime. Other languages, e.g., python or expert system shells, which include this functionality, will shorten the code and raise efficiency and maintainability. Furthermore, especially code generation and an automatic adaptation of the user interface at runtime could widely automate user interface creation, e.g., to extend the sorting box to five slots even with less effort. In the same way, e.g., python offers a constraint module which includes a backtracking solver, recursive backtracking solver and minimum conflicts solver as well as 10 different constraint types. A module for remote controlling Autodesk Inventor is also available, a comparative study of implementing the above design task is an obvious avenue.

The example of the sorting box can easily be extended by, e.g., pricing information that is calculated with respect to the user selections. Therefore, the domains need to be extended by the corresponding part costs, which have to be added by the configuration system. As an example, to include non-geometric features like services, it would be conceivable to choose between a neutral standard package and a package that shows the actual configured sorting box. The described extension to 10 domains involves multiple adjustments to the code. From a theoretical perspective, an extension to 1000 domains seems not adequate. However, taking into account that many combinatorial design tasks in mechanical engineering can be broken down to 10 to 25 core components on an assembly level, a relevant field of application exists, independently from the implementation in VBA or a higher language.

Further interesting issues lie in coupling different inference mechanisms to the CSP-based configuration system and decentralizing its knowledge base as the CAD system itself can control, e.g., part or feature occurrences by rules or other scripting. Additionally, case-based reasoning would be an interesting approach to include a dynamic generation of template configurations depending on, e.g., configuration history, user ratings or overall most favorite configurations. Including data about the user, this could be further developed to a recommendation system.

Concluding, the application of CSP-based configuration using just the functionalities of a standard CAD system has the potential of automating combinatorial designs and integrate knowledge-based CAD assemblies with high efficiency. The approach is compatible with existing and usually familiar tools, thus easy in its application and extendible. In such a way, managing the combinatorial complexity of a design solution space is possible.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The code for the example, the Autodesk Inventor assembly file and the excel repository is publicly available via https://doi.org/10.25835/6wdfdp03 (last accessed on 4 September 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Code for Module Main

Table A1.

VBA Code for Module Main.

Table A1.

VBA Code for Module Main.

| Row | Code |

|---|---|

| 1 | ‘For Dictionary Use activate: |

| 2 | ‘Extras -> References -> Microsoft Scripting Runtime |

| 3 | |

| 4 | ‘Generate Dictionaries for all Components |

| 5 | Public dict_Slots1 As New Dictionary, dict_Slots2 As New Dictionary |

| 6 | Public dict_Slots3 As New Dictionary, dict_Slots4 As New Dictionary |

| 7 | Public dict_SlotsORI As New Dictionary |

| 8 | Public dict_Bricks1 As New Dictionary, dict_Bricks2 As New Dictionary |

| 9 | Public dict_Bricks3 As New Dictionary, dict_Bricks4 As New Dictionary |

| 10 | Public dict_BricksORI As New Dictionary |

| 11 | |

| 12 | ‘Generate Constraint Handling |

| 13 | Public dict_ConList As New Dictionary |

| 14 | Public dict_ConQue As New Dictionary |

| 15 | |

| 16 | ‘Internal Selection Working Memory |

| 17 | Public strSlot1, strSlot2, strSlot3, strSlot4 As String |

| 18 | Public strBrick1, strBrick2, strBrick3, strBrick4 As String |

| 19 | |

| 20 | ‘Global Counter |

| 21 | Public count_Slots As Integer |

| 22 | |

| 23 | |

| 24 | Sub reset() |

| 25 | ‘Clear all Dicitonaries |

| 26 | dict_Slots1.RemoveAll |

| 27 | dict_Slots2.RemoveAll |

| 28 | dict_Slots3.RemoveAll |

| 29 | dict_Slots4.RemoveAll |

| 30 | dict_SlotsORI.RemoveAll |

| 31 | dict_Bricks1.RemoveAll |

| 32 | dict_Bricks2.RemoveAll |

| 33 | dict_Bricks3.RemoveAll |

| 34 | dict_Bricks4.RemoveAll |

| 35 | dict_BricksORI.RemoveAll |

| 36 | dict_ConQue.RemoveAll |

| 37 | dict_ConList.RemoveAll |

| 38 | |

| 39 | ‘Clear User Interface |

| 40 | UserForm1.lbx_Slots1.Clear |

| 41 | UserForm1.lbx_Slots2.Clear |

| 42 | UserForm1.lbx_Slots3.Clear |

| 43 | UserForm1.lbx_Slots4.Clear |

| 44 | UserForm1.lbx_Bricks1.Clear |

| 45 | UserForm1.lbx_Bricks2.Clear |

| 46 | UserForm1.lbx_Bricks3.Clear |

| 47 | UserForm1.lbx_Bricks4.Clear |

| 48 | UserForm1.lbl_Slots1.Caption = ““ |

| 49 | UserForm1.lbl_Slots2.Caption = ““ |

| 50 | UserForm1.lbl_Slots3.Caption = ““ |

| 51 | UserForm1.lbl_Slots4.Caption = ““ |

| 52 | UserForm1.lbl_Bricks1.Caption = ““ |

| 53 | UserForm1.lbl_Bricks2.Caption = ““ |

| 54 | UserForm1.lbl_Bricks3.Caption = ““ |

| 55 | UserForm1.lbl_Bricks4.Caption = ““ |

| 56 | |

| 57 | ‘Reset Global Counter |

| 58 | count_Slots = 0 |

| 59 | End Sub |

| 60 | |

| 61 | |

| 62 | Sub read_inventory() |

| 63 | Dim ExcWB As Excel.Workbook |

| 64 | ‘------------------------------------------------------- |

| 65 | ‘ADJUST PATH TO LOCAL PATH OF THE REPOSITORY FILE BELOW! |

| 66 | ‘------------------------------------------------------- |

| 67 | Set ExcWB = Workbooks.Open(“…\Inventory_List.xlsx”) |

| 68 | |

| 69 | ‘Call creating subs |

| 70 | generate_domains ExcWB.Worksheets(“Slots”) |

| 71 | generate_Brickss ExcWB.Worksheets(“Bricks”) |

| 72 | get_constraints ExcWB.Worksheets(“_CONSTRAINTS_”) |

| 73 | |

| 74 | ‘Close Workbook |

| 75 | ExcWB.Close |

| 76 | End Sub |

| 77 | |

| 78 | |

| 79 | Sub generate_domains(ByVal ExcWS As Excel.WorkSheet) |

| 80 | Dim iRow As Integer |

| 81 | Dim key As Variant |

| 82 | |

| 83 | ‘Set Start for reading in second row |

| 84 | iRow = 2 |

| 85 | ‘Get Slot Domain Master |

| 86 | Do Until ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 1).Value = ““ |

| 87 | ArticleID = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 1).Value |

| 88 | Set oPart1 = New iComponent_Slots |

| 89 | oPart1.Slots_Colour = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 2).Value |

| 90 | oPart1.Slots_Shape = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 3).Value |

| 91 | dict_SlotsORI.Add ArticleID, oPart1 |

| 92 | iRow = iRow + 1 |

| 93 | Loop |

| 94 | |

| 95 | ‘Distribute Master to all 4 Slot Domains |

| 96 | For Each key In dict_SlotsORI |

| 97 | dict_Slots1.Add (key), dict_SlotsORI(key) |

| 98 | Next |

| 99 | For Each key In dict_SlotsORI |

| 100 | dict_Slots2.Add (key), dict_SlotsORI(key) |

| 101 | Next |

| 102 | For Each key In dict_SlotsORI |

| 103 | dict_Slots3.Add (key), dict_SlotsORI(key) |

| 104 | Next |

| 105 | For Each key In dict_SlotsORI |

| 106 | dict_Slots4.Add (key), dict_SlotsORI(key) |

| 107 | Next |

| 108 | |

| 109 | End Sub |

| 110 | |

| 111 | |

| 112 | Sub generate_Brickss(ByVal ExcWS As Excel.WorkSheet) |

| 113 | Dim iRow As Integer |

| 114 | Dim key As Variant |

| 115 | |

| 116 | ‘Set Start for reading in second row |

| 117 | iRow = 2 |

| 118 | ‘Get Brick Domain Master |

| 119 | Do Until ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 1).Value = ““ |

| 120 | ArticleID = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 1).Value |

| 121 | Set oPart1 = New iComponent_Bricks |

| 122 | oPart1.Bricks_Colour = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 2).Value |

| 123 | oPart1.Bricks_Shape = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 3).Value |

| 124 | oPart1.Bricks_Infill = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 4).Value |

| 125 | dict_BricksORI.Add ArticleID, oPart1 |

| 126 | iRow = iRow + 1 |

| 127 | Loop |

| 128 | |

| 129 | ‘Distribute Master to all 4 Brick Domains |

| 130 | For Each key In dict_BricksORI |

| 131 | dict_Bricks1.Add (key), dict_BricksORI(key) |

| 132 | Next |

| 133 | For Each key In dict_BricksORI |

| 134 | dict_Bricks2.Add (key), dict_BricksORI(key) |

| 135 | Next |

| 136 | For Each key In dict_BricksORI |

| 137 | dict_Bricks3.Add (key), dict_BricksORI(key) |

| 138 | Next |

| 139 | For Each key In dict_BricksORI |

| 140 | dict_Bricks4.Add (key), dict_BricksORI(key) |

| 141 | Next |

| 142 | |

| 143 | End Sub |

| 144 | |

| 145 | Sub get_constraints(ByVal ExcWS As Excel.WorkSheet) |

| 146 | Dim ConPa As iConstraint |

| 147 | ‘Set Start for reading in second row |

| 148 | iRow = 2 |

| 149 | KeyID = 1 |

| 150 | |

| 151 | ‘Get Constraints from Repository |

| 152 | Do Until ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 1).Value = ““ |

| 153 | |

| 154 | ‘------ EQUALITIES / INEQUALITIES ------ |

| 155 | If ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 2) = “equal” Or ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 2) = “unequal” Then |

| 156 | ‘Formalize for Processing in VBA |

| 157 | Set oConstraint1 = New iConstraint |

| 158 | ‘Assign Source Domain |

| 159 | Select Case ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 4) |

| 160 | Case “Slots1” |

| 161 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Slots1 |

| 162 | Case “Slots2” |

| 163 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Slots2 |

| 164 | Case “Slots3” |

| 165 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Slots3 |

| 166 | Case “Slots4” |

| 167 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Slots4 |

| 168 | Case “Bricks1” |

| 169 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Bricks1 |

| 170 | Case “Bricks2” |

| 171 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Bricks2 |

| 172 | Case “Bricks3” |

| 173 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Bricks3 |

| 174 | Case “Bricks4” |

| 175 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Bricks4 |

| 176 | End Select |

| 177 | oConstraint1.ConArg1Str = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 4) |

| 178 | ‘Assign Target Domain |

| 179 | Select Case ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 5) |

| 180 | Case “Slots1” |

| 181 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Slots1 |

| 182 | Case “Slots2” |

| 183 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Slots2 |

| 184 | Case “Slots3” |

| 185 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Slots3 |

| 186 | Case “Slots4” |

| 187 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Slots4 |

| 188 | Case “Bricks1” |

| 189 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Bricks1 |

| 190 | Case “Bricks2” |

| 191 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Bricks2 |

| 192 | Case “Bricks3” |

| 193 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Bricks3 |

| 194 | Case “Bricks4” |

| 195 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Bricks4 |

| 196 | End Select |

| 197 | oConstraint1.ConArg2Str = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 5) |

| 198 | ‘Get Expression |

| 199 | oConstraint1.ConExpr = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 2) |

| 200 | ‘Add to Constraint List |

| 201 | dict_ConList.Add KeyID, oConstraint1 |

| 202 | KeyID = KeyID + 1 |

| 203 | |

| 204 | ‘If binary get inverse Constraint |

| 205 | If ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 3) = “TRUE” Then |

| 206 | Set oConstraint1 = New iConstraint |

| 207 | Select Case ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 5) |

| 208 | Case “Slots1” |

| 209 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Slots1 |

| 210 | Case “Slots2” |

| 211 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Slots2 |

| 212 | Case “Slots3” |

| 213 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Slots3 |

| 214 | Case “Slots4” |

| 215 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Slots4 |

| 216 | Case “Bricks1” |

| 217 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Bricks1 |

| 218 | Case “Bricks2” |

| 219 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Bricks2 |

| 220 | Case “Bricks3” |

| 221 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Bricks3 |

| 222 | Case “Bricks4” |

| 223 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg1 = dict_Bricks4 |

| 224 | End Select |

| 225 | oConstraint1.ConArg1Str = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 5) |

| 226 | Select Case ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 4) |

| 227 | Case “Slots1” |

| 228 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Slots1 |

| 229 | Case “Slots2” |

| 230 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Slots2 |

| 231 | Case “Slots3” |

| 232 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Slots3 |

| 233 | Case “Slots4” |

| 234 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Slots4 |

| 235 | Case “Bricks1” |

| 236 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Bricks1 |

| 237 | Case “Bricks2” |

| 238 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Bricks2 |

| 239 | Case “Bricks3” |

| 240 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Bricks3 |

| 241 | Case “Bricks4” |

| 242 | Set oConstraint1.ConArg2 = dict_Bricks4 |

| 243 | End Select |

| 244 | oConstraint1.ConArg2Str = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 4) |

| 245 | oConstraint1.ConExpr = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 2) |

| 246 | dict_ConList.Add KeyID, oConstraint1 |

| 247 | KeyID = KeyID + 1 |

| 248 | End If |

| 249 | End If |

| 250 | |

| 251 | ‘------ OBLIGATIONS ------ |

| 252 | If ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 2) = “obligation” Then |

| 253 | Set oConstraint1 = New iConstraint |

| 254 | ‘Get Arguments |

| 255 | oConstraint1.ConArg1Str = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 4) |

| 256 | oConstraint1.ConArg2Str = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 5) |

| 257 | oConstraint1.ConArg3Str = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 6) |

| 258 | oConstraint1.ConArg4Str = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 7) |

| 259 | ‘Get Get Expression |

| 260 | oConstraint1.ConExpr = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 2) |

| 261 | oConstraint1.ConIndex = ExcWS.Cells(iRow, 1) |

| 262 | ‘Add to Constraint List |

| 263 | dict_ConList.Add KeyID, oConstraint1 |

| 264 | KeyID = KeyID + 1 |

| 265 | End If |

| 266 | |

| 267 | iRow = iRow + 1 |

| 268 | Loop |

| 269 | count_Slots = 0 |

| 270 | |

| 271 | End Sub |

| 272 | |

| 273 | |

| 274 | Sub update_Listboxes() |

| 275 | ‘Update Content of the User Interface |

| 276 | ‘Update Slots |

| 277 | UserForm1.lbx_Slots1.Clear |

| 278 | ‘Repopulate Listbox from Domain |

| 279 | For Each key In dict_Slots1 |

| 280 | Set oComp = dict_Slots1(key) |

| 281 | UserForm1.lbx_Slots1.AddItem (oComp.Slots_Colour) |

| 282 | Next |

| 283 | UserForm1.lbx_Slots2.Clear |

| 284 | For Each key In dict_Slots2 |

| 285 | Set oComp = dict_Slots2(key) |

| 286 | UserForm1.lbx_Slots2.AddItem (oComp.Slots_Colour) |

| 287 | Next |

| 288 | UserForm1.lbx_Slots3.Clear |

| 289 | For Each key In dict_Slots3 |

| 290 | Set oComp = dict_Slots3(key) |

| 291 | UserForm1.lbx_Slots3.AddItem (oComp.Slots_Colour) |

| 292 | Next |

| 293 | UserForm1.lbx_Slots4.Clear |

| 294 | For Each key In dict_Slots4 |

| 295 | Set oComp = dict_Slots4(key) |

| 296 | UserForm1.lbx_Slots4.AddItem (oComp.Slots_Colour) |

| 297 | Next |

| 298 | |

| 299 | ‘Update Bricks |

| 300 | UserForm1.lbx_Bricks1.Clear |

| 301 | For Each key In dict_Bricks1 |

| 302 | Set oComp = dict_Bricks1(key) |

| 303 | UserForm1.lbx_Bricks1.AddItem (oComp.Bricks_Colour & “ | “ & oComp.Bricks_Infill) |

| 304 | Next |

| 305 | UserForm1.lbx_Bricks2.Clear |

| 306 | For Each key In dict_Bricks2 |

| 307 | Set oComp = dict_Bricks2(key) |

| 308 | UserForm1.lbx_Bricks2.AddItem (oComp.Bricks_Colour & “ | “ & oComp.Bricks_Infill) |

| 309 | Next |

| 310 | UserForm1.lbx_Bricks3.Clear |

| 311 | For Each key In dict_Bricks3 |

| 312 | Set oComp = dict_Bricks3(key) |

| 313 | UserForm1.lbx_Bricks3.AddItem (oComp.Bricks_Colour & “ | “ & oComp.Bricks_Infill) |

| 314 | Next |

| 315 | UserForm1.lbx_Bricks4.Clear |

| 316 | For Each key In dict_Bricks4 |

| 317 | Set oComp = dict_Bricks4(key) |

| 318 | UserForm1.lbx_Bricks4.AddItem (oComp.Bricks_Colour & “ | “ & oComp.Bricks_Infill) |

| 319 | Next |

| 320 | End Sub |

| 321 | |

| 322 | |

| 323 | Public Sub Constraint_Solver() |

| 324 | |

| 325 | Dim key As Variant |

| 326 | Dim arg1 As Dictionary, arg2 As Dictionary, arg3 As Dictionary, arg4 As Dictionary |

| 327 | Dim arg1str, arg2str, arg3str, arg4str As String |

| 328 | Dim ConExpr As String |

| 329 | Dim oComp As iComponent_Slots |

| 330 | Dim ConPa As iConstraint |

| 331 | ‘As long as Queue is not empty |

| 332 | Do While dict_ConQue.Count <> 0 |

| 333 | For Each key In dict_ConQue |

| 334 | ‘Get Arguments from Constraint in Queue |

| 335 | Set ConPa = dict_ConQue(key) |

| 336 | Set arg1 = ConPa.ConArg1 |

| 337 | Set arg2 = ConPa.ConArg2 |

| 338 | Set arg3 = ConPa.ConArg3 |

| 339 | Set arg4 = ConPa.ConArg4 |

| 340 | arg1str = ConPa.ConArg1Str |

| 341 | arg2str = ConPa.ConArg2Str |

| 342 | arg3str = ConPa.ConArg3Str |

| 343 | arg4str = ConPa.ConArg4Str |

| 344 | ConExpr = ConPa.ConExpr |

| 345 | ‘Get Expression for processing |

| 346 | Select Case ConExpr |

| 347 | ‘Unequality |

| 348 | Case “unequal” |

| 349 | ‘Delete Constraint from Queue |

| 350 | dict_ConQue.Remove (key) |

| 351 | ‘Call Processing |

| 352 | Call Del_Equal_Slots(arg1, arg2) |

| 353 | ‘Equality |

| 354 | Case “equal” |

| 355 | dict_ConQue.Remove (key) |

| 356 | Call Bricks_to_Slots(arg1, arg2) |

| 357 | ‘Obligatory Assignment |

| 358 | Case “obligation” |

| 359 | dict_ConQue.Remove (key) |

| 360 | Call Set_Obliged_Slots(arg1str, arg2str, arg3str, arg4str) |

| 361 | Case Else |

| 362 | dict_ConQue.Remove (key) |

| 363 | End Select |

| 364 | Next |

| 365 | Loop |

| 366 | ‘Update User Interface |

| 367 | update_Listboxes |

| 368 | |

| 369 | End Sub |

| 370 | |

| 371 | |

| 372 | Sub Constraint_Relax() |

| 373 | ‘------ Repopulte reset Domain ------ |

| 374 | ‘Evaluate if Domain is NOT collapsed |

| 375 | If strSlot1 = ““ Then |

| 376 | ‘Refresh the domain including reset selection |

| 377 | ‘for slot |

| 378 | dict_Slots1.RemoveAll |

| 379 | For Each key In dict_SlotsORI |

| 380 | dict_Slots1.Add (key), dict_SlotsORI(key) |

| 381 | Next |

| 382 | ‘for brick |

| 383 | dict_Bricks1.RemoveAll |

| 384 | For Each key In dict_BricksORI |

| 385 | dict_Bricks1.Add (key), dict_BricksORI(key) |

| 386 | Next |

| 387 | End If |

| 388 | |

| 389 | If strSlot2 = ““ Then |

| 390 | dict_Slots2.RemoveAll |

| 391 | For Each key In dict_SlotsORI |

| 392 | dict_Slots2.Add (key), dict_SlotsORI(key) |

| 393 | Next |

| 394 | dict_Bricks2.RemoveAll |

| 395 | For Each key In dict_BricksORI |

| 396 | dict_Bricks2.Add (key), dict_BricksORI(key) |

| 397 | Next |

| 398 | End If |

| 399 | |

| 400 | If strSlot3 = ““ Then |

| 401 | dict_Slots3.RemoveAll |

| 402 | For Each key In dict_SlotsORI |

| 403 | dict_Slots3.Add (key), dict_SlotsORI(key) |

| 404 | Next |

| 405 | dict_Bricks3.RemoveAll |

| 406 | For Each key In dict_BricksORI |

| 407 | dict_Bricks3.Add (key), dict_BricksORI(key) |

| 408 | Next |

| 409 | End If |

| 410 | |

| 411 | If strSlot4 = ““ Then |

| 412 | dict_Slots4.RemoveAll |

| 413 | For Each key In dict_SlotsORI |

| 414 | dict_Slots4.Add (key), dict_SlotsORI(key) |

| 415 | Next |

| 416 | dict_Bricks4.RemoveAll |

| 417 | For Each key In dict_BricksORI |

| 418 | dict_Bricks4.Add (key), dict_BricksORI(key) |

| 419 | Next |

| 420 | End If |

| 421 | |

| 422 | ‘------ Add relevant Constraints to queue ------ |

| 423 | Dim oConstr As iConstraint |

| 424 | ‘if the domain is already occupied by a selection |

| 425 | ‘then add relevant constraints to queue where this is source |

| 426 | If Not strSlot1 = ““ Then |

| 427 | Call Un_Constraint(dict_Slots1, strSlot1) |

| 428 | For Each key In dict_ConList |

| 429 | Set oConstr = dict_ConList(key) |

| 430 | If oConstr.ConArg1Str = “Slots1” Then |

| 431 | dict_ConQue.Add (key), dict_ConList(key) |

| 432 | End If |

| 433 | Next |

| 434 | End If |

| 435 | |

| 436 | If Not strSlot2 = ““ Then |

| 437 | Call Un_Constraint(dict_Slots2, strSlot2) |

| 438 | For Each key In dict_ConList |

| 439 | Set oConstr = dict_ConList(key) |

| 440 | If oConstr.ConArg1Str = “Slots2” Then |

| 441 | dict_ConQue.Add (key), dict_ConList(key) |

| 442 | End If |

| 443 | Next |

| 444 | End If |

| 445 | |

| 446 | If Not strSlot3 = ““ Then |

| 447 | Call Un_Constraint(dict_Slots3, strSlot3) |

| 448 | For Each key In dict_ConList |

| 449 | Set oConstr = dict_ConList(key) |

| 450 | If oConstr.ConArg1Str = “Slots3” Then |

| 451 | dict_ConQue.Add (key), dict_ConList(key) |

| 452 | End If |

| 453 | Next |

| 454 | End If |

| 455 | |

| 456 | If Not strSlot4 = ““ Then |

| 457 | Call Un_Constraint(dict_Slots4, strSlot4) |

| 458 | For Each key In dict_ConList |

| 459 | Set oConstr = dict_ConList(key) |

| 460 | If oConstr.ConArg1Str = “Slots4” Then |

| 461 | dict_ConQue.Add (key), dict_ConList(key) |

| 462 | End If |

| 463 | Next |

| 464 | End If |

| 465 | |

| 466 | ‘Start Solver |

| 467 | Constraint_Solver |

| 468 | End Sub |

| 469 | |

| 470 | |

| 471 | Sub Un_Constraint(ByRef arg1 As Dictionary, ByVal ConVal As String) |

| 472 | ‘Collapses Domain according to node consistency |

| 473 | Dim key As Variant |

| 474 | Dim oComp As iComponent_Slots |

| 475 | For Each key In arg1 |

| 476 | Set oComp = arg1(key) |

| 477 | If Not oComp.Slots_Colour = ConVal Then |

| 478 | arg1.Remove (key) |

| 479 | End If |

| 480 | Next |

| 481 | End Sub |

| 482 | |

| 483 | |

| 484 | Sub Del_Equal_Slots(ByRef arg1 As Dictionary, ByRef arg2 As Dictionary) |

| 485 | ‘Elimitates values equal to the reference domain |

| 486 | Dim key1 As Variant, key2 As Variant |

| 487 | Dim oComp1 As iComponent_Slots, oComp2 As iComponent_Slots |

| 488 | For Each key1 In arg1 |

| 489 | Set oComp1 = arg1(key1) |

| 490 | For Each key2 In arg2 |

| 491 | Set oComp2 = arg2(key2) |

| 492 | If oComp1.Slots_Colour = oComp2.Slots_Colour Then |

| 493 | arg2.Remove (key2) |

| 494 | End If |

| 495 | Next |

| 496 | Next |

| 497 | |

| 498 | End Sub |

| 499 | |

| 500 | |

| 501 | Sub Bricks_to_Slots(ByRef arg1 As Dictionary, ByRef arg2 As Dictionary) |

| 502 | ‘Elimitates values unequal to the reference domain |

| 503 | Dim key1 As Variant, key2 As Variant |

| 504 | Dim oComp1 As iComponent_Slots |

| 505 | Dim oComp2 As iComponent_Bricks |

| 506 | For Each key1 In arg1 |

| 507 | Set oComp1 = arg1(key1) |

| 508 | For Each key2 In arg2 |

| 509 | Set oComp2 = arg2(key2) |

| 510 | If Not oComp1.Slots_Colour = oComp2.Bricks_Colour Then |

| 511 | arg2.Remove (key2) |

| 512 | End If |

| 513 | Next |

| 514 | Next |

| 515 | |

| 516 | End Sub |

| 517 | |

| 518 | Sub Set_Obliged_Slots(ByVal arg1str As String, ByVal arg2str As String, _ |

| 519 | ByVal arg3str As String, ByVal arg4str As String) |

| 520 | |

| 521 | ‘Assigns missing value from template |

| 522 | |

| 523 | Dim key1, key2, key3, key4 As Variant |

| 524 | Dim KeyA, KeyB As Variant |

| 525 | Dim oComp1 As iComponent_Slots, oComp2 As iComponent_Slots, oComp3 As _ |

| 526 | iComponent_Slots, oComp4 As iComponent_Slots, oCompA As iComponent_Slots |

| 527 | |

| 528 | Dim dict_comp As New Dictionary |

| 529 | Dim dict_set As New Dictionary |

| 530 | |

| 531 | ‘establish comparative dictionary from constraint arguments |

| 532 | ‘if this domain has an assigned value write it to the comparative dictionary |

| 533 | If dict_Slots1.Count = 1 Then |

| 534 | For Each key1 In dict_Slots1 |

| 535 | Set oComp1 = dict_Slots1(key1) |

| 536 | ‘get colour independently from sequence or position |

| 537 | If oComp1.Slots_Colour = arg1str Or oComp1.Slots_Colour = arg2str Or _ |

| 538 | oComp1.Slots_Colour = arg3str Or oComp1.Slots_Colour = arg4str Then |

| 539 | dict_comp.Add (key1), dict_Slots1(key1) |

| 540 | End If |

| 541 | Next |

| 542 | End If |

| 543 | If dict_Slots2.Count = 1 Then |

| 544 | For Each key2 In dict_Slots2 |

| 545 | Set oComp2 = dict_Slots2(key2) |

| 546 | If oComp2.Slots_Colour = arg1str Or oComp2.Slots_Colour = arg2str Or _ |

| 547 | oComp2.Slots_Colour = arg3str Or oComp2.Slots_Colour = arg4str Then |

| 548 | dict_comp.Add (key2), dict_Slots2(key2) |

| 549 | End If |

| 550 | Next |

| 551 | End If |

| 552 | If dict_Slots3.Count = 1 Then |

| 553 | For Each key3 In dict_Slots3 |

| 554 | Set oComp3 = dict_Slots3(key3) |

| 555 | If oComp3.Slots_Colour = arg1str Or oComp3.Slots_Colour = arg2str Or _ |

| 556 | oComp3.Slots_Colour = arg3str Or oComp3.Slots_Colour = arg4str Then |

| 557 | dict_comp.Add (key3), dict_Slots3(key3) |

| 558 | End If |

| 559 | Next |

| 560 | End If |

| 561 | If dict_Slots4.Count = 1 Then |

| 562 | For Each key4 In dict_Slots4 |

| 563 | Set oComp4 = dict_Slots4(key4) |

| 564 | If oComp4.Slots_Colour = arg1str Or oComp4.Slots_Colour = arg2str Or _ |

| 565 | oComp4.Slots_Colour = arg3str Or oComp4.Slots_Colour = arg4str Then |

| 566 | dict_comp.Add (key4), dict_Slots4(key4) |

| 567 | End If |

| 568 | Next |

| 569 | End If |

| 570 | |

| 571 | ‘check if three slots have been assigned |

| 572 | If dict_comp.Count = 3 Then |

| 573 | ‘establish control dictionary for value retrieval |

| 574 | For Each key In dict_SlotsORI |

| 575 | Set oCompA = dict_SlotsORI(key) |

| 576 | If oCompA.Slots_Colour = arg1str Or oCompA.Slots_Colour = arg2str Or _ |

| 577 | oCompA.Slots_Colour = arg3str Or oCompA.Slots_Colour = arg4str Then |

| 578 | dict_set.Add (key), dict_SlotsORI(key) |

| 579 | End If |

| 580 | Next |

| 581 | |

| 582 | ‘identify missing assignment |

| 583 | For Each KeyA In dict_comp |

| 584 | dict_set.Remove (KeyA) |

| 585 | Next |

| 586 | |

| 587 | ‘set assignment |

| 588 | For Each KeyA In dict_set |

| 589 | Set oCompA = dict_set(KeyA) |

| 590 | ‘if slot one is the open one then assign last value here and collapse |

| 591 | If Not dict_Slots1.Count = 1 Then |

| 592 | For Each key1 In dict_Slots1 |

| 593 | Set oComp1 = dict_Slots1(key1) |

| 594 | If Not oComp1.Slots_Colour = oCompA.Slots_Colour Then |

| 595 | dict_Slots1.Remove (key1) |

| 596 | End If |

| 597 | Next |

| 598 | End If |

| 599 | If Not dict_Slots2.Count = 1 Then |

| 600 | For Each key2 In dict_Slots2 |

| 601 | Set oComp2 = dict_Slots2(key2) |

| 602 | If Not oComp2.Slots_Colour = oCompA.Slots_Colour Then |

| 603 | dict_Slots2.Remove (key2) |

| 604 | End If |

| 605 | Next |

| 606 | End If |

| 607 | If Not dict_Slots3.Count = 1 Then |

| 608 | For Each key3 In dict_Slots3 |

| 609 | Set oComp3 = dict_Slots3(key3) |

| 610 | If Not oComp3.Slots_Colour = oCompA.Slots_Colour Then |

| 611 | dict_Slots3.Remove (key3) |

| 612 | End If |

| 613 | Next |

| 614 | End If |

| 615 | If Not dict_Slots4.Count = 1 Then |

| 616 | For Each key4 In dict_Slots4 |

| 617 | Set oComp4 = dict_Slots4(key4) |

| 618 | If Not oComp4.Slots_Colour = oCompA.Slots_Colour Then |

| 619 | dict_Slots4.Remove (key4) |

| 620 | End If |

| 621 | Next |

| 622 | End If |

| 623 | Next |

| 624 | End If |

| 625 | End Sub |

Appendix B. Code for Userform1

Table A2.

VBA Code for Userform1.

Table A2.

VBA Code for Userform1.

| Row | Code |

|---|---|

| 1 | Private Sub cmd_gen_domains_Click() |

| 2 | ‘Generates the Domains from the Excel Repository and inits User Interface |

| 3 | Main.reset |

| 4 | Main.read_inventory |

| 5 | Main.update_Listboxes |

| 6 | End Sub |

| 7 | |

| 8 | Private Sub cmd_relax1_1_Click() |

| 9 | ‘Reset Label in User Interface and Internal Selection Working Memory |

| 10 | lbl_Slots1.Caption = ““ |

| 11 | strSlot1 = ““ |

| 12 | ‘decrease global counter by one |

| 13 | count_Slots = count_Slots − 1 |

| 14 | ‘Refreshopen Domains |

| 15 | Main.Constraint_Relax |

| 16 | End Sub |

| 17 | |

| 18 | Private Sub cmd_relax1_2_Click() |

| 19 | lbl_Slots2.Caption = ““ |

| 20 | strSlot2 = ““ |

| 21 | count_Slots = count_Slots − 1 |

| 22 | Main.Constraint_Relax |

| 23 | End Sub |

| 24 | |

| 25 | Private Sub cmd_relax1_3_Click() |

| 26 | lbl_Slots3.Caption = ““ |

| 27 | strSlot3 = ““ |

| 28 | count_Slots = count_Slots − 1 |

| 29 | Main.Constraint_Relax |

| 30 | End Sub |

| 31 | |

| 32 | Private Sub cmd_relax1_4_Click() |

| 33 | lbl_Slots4.Caption = ““ |

| 34 | strSlot4 = ““ |

| 35 | count_Slots = count_Slots − 1 |

| 36 | Main.Constraint_Relax |

| 37 | End Sub |

| 38 | |

| 39 | Private Sub cmd_reset_Click() |

| 40 | ‘Empty Domains, Queue and User Interface |

| 41 | reset |

| 42 | End Sub |

| 43 | |

| 44 | |

| 45 | Private Sub lbx_Slots1_DblClick(ByVal Cancel As MSForms.ReturnBoolean) |

| 46 | ‘Selection of a Domain Variable and Queueing of Neighbours |

| 47 | ‘Add Selection to Label in User Interface and Internal Selection Working Memory |

| 48 | lbl_Slots1.Caption = lbx_Slots1.Text |

| 49 | strSlot1 = lbx_Slots1.Text |

| 50 | ‘Add unary Constraint to Queue for Collapsing |

| 51 | Call Main.Un_Constraint(dict_Slots1, strSlot1) |

| 52 | ‘Increase global counter by one |

| 53 | count_Slots = count_Slots + 1 |

| 54 | ‘Add relevant binary Constraints to Queue |

| 55 | Dim oConstr As iConstraint |

| 56 | For Each key In dict_ConList |

| 57 | Set oConstr = dict_ConList(key) |

| 58 | If oConstr.ConArg1Str = “Slots1” Then |

| 59 | dict_ConQue.Add (key), dict_ConList(key) |

| 60 | End If |

| 61 | If count_Slots = 3 Then |

| 62 | If oConstr.ConExpr = “obligation” Then |

| 63 | dict_ConQue.Add (key), dict_ConList(key) |

| 64 | End If |

| 65 | End If |

| 66 | Next |

| 67 | ‘Start Solver |

| 68 | Main.Constraint_Solver |

| 69 | End Sub |

| 70 | |

| 71 | |

| 72 | Private Sub lbx_Slots2_DblClick(ByVal Cancel As MSForms.ReturnBoolean) |

| 73 | lbl_Slots2.Caption = lbx_Slots2.Text |

| 74 | strSlot2 = lbx_Slots2.Text |

| 75 | Call Main.Un_Constraint(dict_Slots2, strSlot2) |

| 76 | count_Slots = count_Slots + 1 |

| 77 | Dim oConstr As iConstraint |

| 78 | For Each key In dict_ConList |

| 79 | Set oConstr = dict_ConList(key) |

| 80 | If oConstr.ConArg1Str = “Slots2” Then |

| 81 | dict_ConQue.Add (key), dict_ConList(key) |

| 82 | End If |

| 83 | If count_Slots = 3 Then |

| 84 | If oConstr.ConExpr = “obligation” Then |

| 85 | dict_ConQue.Add (key), dict_ConList(key) |

| 86 | End If |

| 87 | End If |

| 88 | Next |

| 89 | Main.Constraint_Solver |

| 90 | End Sub |

| 91 | |

| 92 | Private Sub lbx_Slots3_DblClick(ByVal Cancel As MSForms.ReturnBoolean) |

| 93 | lbl_Slots3.Caption = lbx_Slots3.Text |

| 94 | strSlot3 = lbx_Slots3.Text |

| 95 | Call Main.Un_Constraint(dict_Slots3, strSlot3) |

| 96 | count_Slots = count_Slots + 1 |

| 97 | Dim oConstr As iConstraint |

| 98 | For Each key In dict_ConList |

| 99 | Set oConstr = dict_ConList(key) |

| 100 | If oConstr.ConArg1Str = “Slots3” Then |

| 101 | dict_ConQue.Add (key), dict_ConList(key) |

| 102 | End If |

| 103 | If count_Slots = 3 Then |

| 104 | If oConstr.ConExpr = “obligation” Then |

| 105 | dict_ConQue.Add (key), dict_ConList(key) |

| 106 | End If |

| 107 | End If |

| 108 | Next |

| 109 | Main.Constraint_Solver |

| 110 | End Sub |

| 111 | |

| 112 | Private Sub lbx_Slots4_DblClick(ByVal Cancel As MSForms.ReturnBoolean) |

| 113 | lbl_Slots4.Caption = lbx_Slots4.Text |

| 114 | strSlot4 = lbx_Slots4.Text |

References

- Hotz, L.; Felfernig, A.; Günter, A.; Tiihonen, J. A short history of configuration technologies. In Knowledge-Based Configuration—From Research to Business Cases; Felfernig, A., Hotz, L., Bagley, C., Tiihonen, J., Eds.; Morgan Kaufmann: Waltham, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Schwede, L.N.; Greve, E.; Krause, E.; Otto, K.; Moon, S.; Albers, A.; Kirchner, E.; Lachmayer, R.; Bursac, N.; Inkermann, D.; et al. How to Use the Levers of Modularity Properly—Linking Modularization to Economic Targets. J. Mech. Des. 2022, 144, 071401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreiber, G. Knowledge engineering. In Foundations of Artificial Intelligence; Van Harmelen, F., Lifschitz, V., Porter, B., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 3, pp. 929–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gembarski, P.C. Three ways of integrating computer-aided design and knowledge-based engineering. In Proceedings of the Design Society: DESIGN Conference; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 1255–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durhuus, B.; Eilers, S. On the entropy of LEGO®. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2014, 45, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pil, F.K.; Holweg, M. Linking product variety to order-fulfillment strategies. Interfaces 2004, 34, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, W.; Bermell-Garcia, P.; van Dijk, R.; Curran, R. A critical review of Knowledge-Based Engineering: An identification of research challenges. Adv. Eng. Inf. 2012, 26, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopgood, A.A. Intelligent Systems for Engineers and Scientists; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott, J. R1: A rule-based configurer of computer systems. Artif. Intell. 1982, 19, 39–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldanondo, M.; Hadj-Hamou, K.; Moynard, G.; Lamothe, J. Mass customization and configuration: Requirement analysis and constraint based modeling propositions. Integr. Comput.-Aided Eng. 2003, 10, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvam, L.; Mortensen, N.H.; Riis, J. Product Customization; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Barták, R.; Salido, M.A.; Rossi, F. Constraint satisfaction techniques in planning and scheduling. J. Intell. Manuf. 2010, 21, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabin, D.; Weigel, R. Product configuration frameworks-a survey. IEEE Intell. Syst. 1998, 13, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orsvärn, K.; Bennick, M.H. Use of Tacton configurator at FLSmidth. In Knowledge-Based Configuration—From Research to Business Cases; Felfernig, A., Hotz, L., Bagley, C., Tiihonen, J., Eds.; Morgan Kaufmann: Waltham, MA, USA, 2014; pp. 211–218. [Google Scholar]

- Schäffer, E.; Shafiee, S.; Mayr, A.; Franke, J. A strategic approach to improve the development of use-oriented knowledge-based engineering configurators (KBEC). Procedia CIRP 2021, 96, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gembarski, P.C.; Li, H.; Lachmayer, R. KBE-Modeling Techniques in Standard CAD-Systems: Case Study—Autodesk Inventor Professional. In Managing Complexity; Bellemare, J., Carrier, S., Nielsen, K., Piller, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirz, M.; Dietrich, W.; Gfrerrer, A.; Lang, J. Integrated Computer-Aided Design in Automotive Development, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Skarka, W. Application of MOKA methodology in generative model creation using CATIA. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2007, 20, 677–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furferi, R.; Governi, L.; Uccheddu, F.; Volpe, Y. Computer-aided design tool for GT ventilation system ductworks. Comput. Aided Des. Appl. 2018, 15, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milton, N. Knowledge Technologies; Polimetrica, S.a.s.: Monza, Italy, 2008; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Cunis, R.; Günter, A.; Strecker, H. Das PLAKON-Buch: Ein Expertensystemkern für Planungs-und Konfigurierungs-Aufgaben in Technischen Domänen; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Schröder, C.; Möller, R.; Lutz, C. A partial logical reconstruction of PLAKON/KONWERK. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Knowledge Representation and Configuration WRKP, Saarbrucken, Germany, 30 August 1996; pp. 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaRocca, G. Knowledge based Engineering: Between AI and CAD. Review of a Language based Technology to Support Engineering Design. Adv. Eng. Inf. 2012, 26, 159–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailsford, S.C.; Potts, C.N.; Smith, B.M. Constraint satisfaction problems: Algorithms and applications. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1999, 119, 557–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Algorithms for constraint-satisfaction problems: A survey. AI Mag. 1992, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, C.J. Automated Configuration Problem Solving, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Juengst, W.E.; Heinrich, M. Using resource balancing to configure modular systems. IEEE Intell. Syst. 1998, 13, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadori, K. Geometry Based Design Automation: Applied to Aircraft Modelling and Optimization. Ph.D. Thesis, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Gembarski, P.C.; Lachmayer, R. Template-Based Design for Design Co-Creation. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Design Creativity (ICDC2018), Bath, UK, 31 January–2 February 2018; pp. 387–394. [Google Scholar]

- Aldanondo, M.; Vareilles, E. Configuration for mass customization: How to extend product configuration towards requirements and process configuration. J. Intell. Manuf. 2008, 19, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pitiot, P.; Aldanondo, M.; Vareilles, E. Concurrent product configuration and process planning: Some optimization experimental results. Comput. Ind. 2014, 65, 610–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloock-Schreiber, D.; Domarkas, L.; Gembarski, P.C.; Lachmayer, R. Enrichment of geometric CAD models for service configuration. In Proceedings of the 21st International Configuration Workshop, Hamburg, Germany, 21 September 2019; pp. 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).