The Efficient Processing of Moving k-Farthest Neighbor Queries in Road Networks †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- This study proposes MOFA to compute valid segments for the query segment in which a query point moves.

- MOFA retrieves candidate facilities once and has a stable query processing time that is independent of the query frequency.

- An extensive empirical evaluation is performed using real-world road networks to demonstrate the superiority of MOFA compared to a conventional solution.

2. Related Works

- Reverse FN (RFN) query [3,4,5,7,8,9,13]. Given a set of facilities F and a query point q, an RFN query retrieves the facilities in F that have q as their farthest neighbor. Recently, RFN queries have attracted increasing attention based on their applicability. Several studies have been conducted to efficiently evaluate RFN queries in Euclidean spaces [3,4,8,9,13] and road networks [5,7].

- Approximate FN query [1,10,11,14]. Given an approximation ratio c () and success probability , a c-approximate FN query retrieves the c-approximate farthest neighbors with a confidence of at least . Approximate FN search algorithms are considered acceptable in high-dimensional spaces because it is typically not feasible to return the exact farthest neighbors in a large set of points. Huang et al. [10,14] developed a reverse-query-aware locality-sensitive hashing scheme for high-dimensional c-approximate FN searches over external memory. They also proposed a heuristic variant that applied data-dependent object selection to reduce the number of data objects. Liu et al. [11] proposed a c-approximate FN algorithm called reverse incremental locality-sensitive hashing for high-dimensional data that employs a continuous search strategy for each projection dimension.

- Aggregate FN query [2,6]. Given a set of query points Q and an aggregate function (e.g., min, max, and sum), the aggregate FN query retrieves a facility f from a set of facilities F such that the aggregate distance from f to all query points in Q is maximized. Gao et al. [2] studied the aggregate FN query in Euclidean space and proposed the smallest-bounding and best-first algorithms. Wang et al. [6] presented effective solutions to aggregate FN queries in road networks.

- Moving spatial query [15,16,17,18]. Various types of moving spatial queries have been studied extensively, including kNN [15,16,17] and range [18] queries. Nutanong et al. [17] developed an incremental safe region-based technique known as the -diagram to process moving kNN queries in Euclidean space and in undirected spatial networks. Yung et al. [18] proposed an algorithm for computing the boundaries, which are referred to as safe exits, of the safe regions of moving-range queries in road networks. The associated studies considered different problem scenarios from those in our study, and their solutions were found to be inappropriate for our problem scenarios.

3. Notation and Formal Problem Description

4. Clustering Facilities and Computing Distances

4.1. Clustering Facilities into Facility Clusters

4.2. Computing Distances between a Facility Cluster and a Border Point of the Query Segment

5. MOFA Algorithm for MkFN Query Processing in Road Networks

| Algorithm 1:. |

| Input: k: number of FNs requested for q, : query segment, F: set of facilities Output: : query result for , i.e.,

|

| Algorithm 2:. |

| Input: k: number of FNs requested for q, : length of , : border point of , : set of facility clusters Output: : set of candidate facilities for , which are obtained from

|

| Algorithm 3:. |

| Input: k: number of FNs requested for q, : query segment, : set of candidate facilities for Output: : set of valid segments for

|

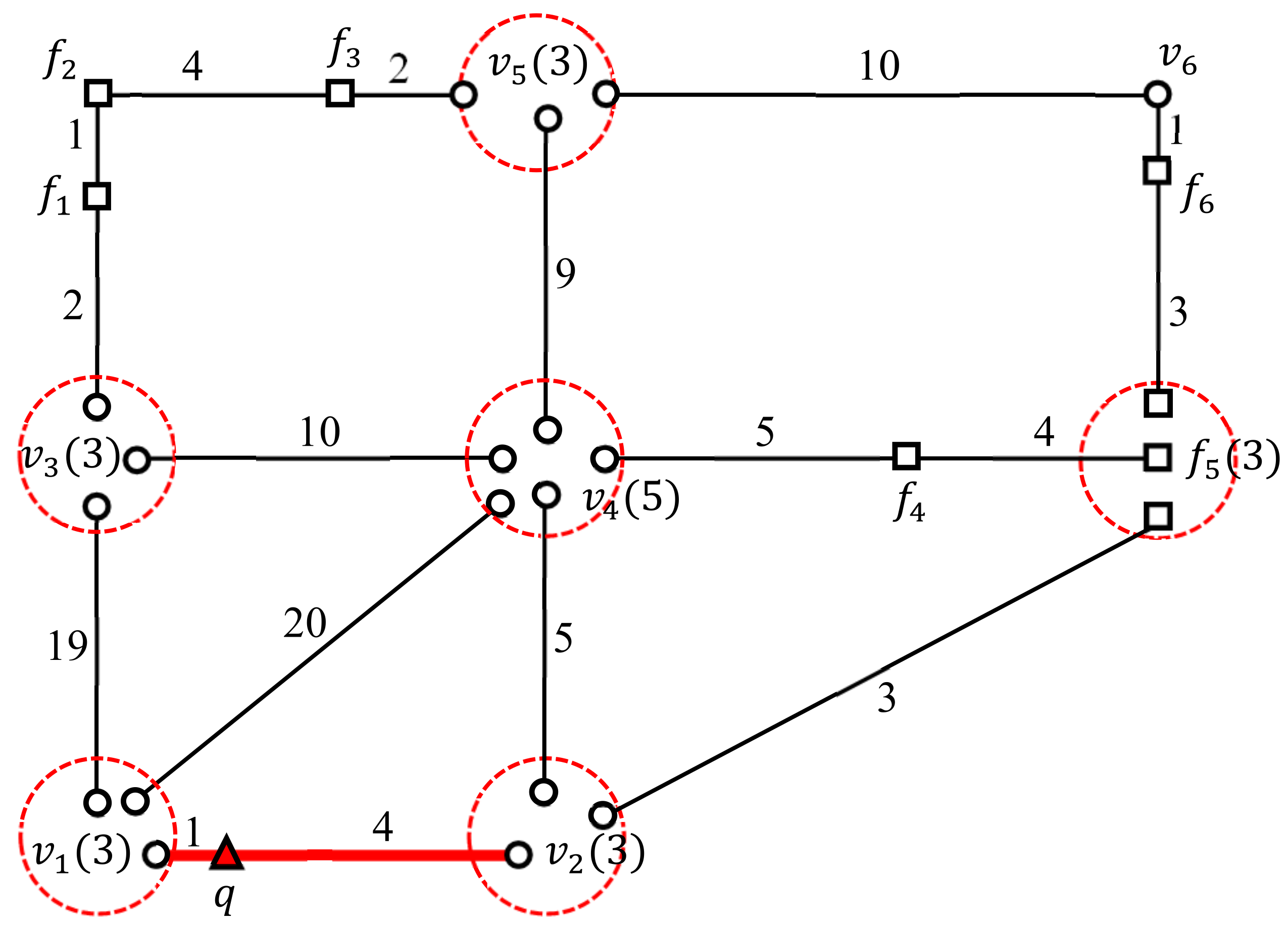

6. Evaluation of the Example MkFN Query Using MOFA

6.1. Finding the Candidate Facilities for the Query Segment

6.2. Computing the Valid Segments for the Query Segment

7. Empirical Evaluation

7.1. Empirical Settings

7.2. Empirical Results

8. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Notation | Definition |

| k | Number of requested facilities farthest from q. |

| q | Moving query point. |

| Query segment in which q moves. | |

| f and F | Facility and a set of facilities, respectively. |

| Vertex list, where and are either an intersection vertex or terminal vertex, | |

| and the other vertices are intermediate vertices with a degree of two. | |

| Facility segment connecting facilities in a vertex list (in short, ). | |

| and | Facility cluster and set of facility clusters, respectively. |

| Set of border points of . | |

| Border point of . | |

| Border point of , where . | |

| Set of candidate facilities for obtained from . | |

| Set of k facilities farthest from a query point q. | |

| Set of k facilities farthest from each query location in , i.e., | |

| . | |

| Network distance between two points q and f. | |

| Largest distance between and . | |

| Smallest distance between and . | |

| Segment length . |

References

- Curtin, R.R.; Echauz, J.R.; Gardner, A.B. Exploiting the structure of furthest neighbor search for fast approximate results. Inf. Syst. 2019, 80, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Shou, L.; Chen, K.; Chen, G. Aggregate farthest-neighbor queries over spatial data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Database Systems for Advanced Applications, Hong Kong, China, 22–25 April 2011; pp. 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Chen, H.; Furuse, K.; Kitagawa, H. An efficient algorithm for arbitrary reverse furthest neighbor queries. In Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Web Conference on Web Technologies and Applications, Kunming, China, 11–13 April 2012; pp. 60–72. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Yuan, Y. New ideas for FN/RFN queries based nearest Voronoi diagram. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Bio-Inspired Computing: Theories and Applications, Huangshan, China, 12–14 July 2013; pp. 917–927. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Q.T.; Taniar, D.; Safar, M. Reverse k nearest neighbor and reverse farthest neighbor search on spatial networks. Trans. Large-Scale Data- Knowl.-Centered Syst. 2009, 1, 353–372. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Zheng, K.; Su, H.; Wang, J.; Sadiq, S.W.; Zhou, X. Efficient aggregate farthest neighbour query processing on road networks. In Proceedings of the Australasian Database Conference on Databases Theory and Applications, Brisbane, Australia, 14–16 July 2014; pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.-J.; Bao, J.; Yao, B.; Zhou, J.; Tang, F.; Guo, M.; Xu, J. Reverse furthest neighbors query in road networks. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2017, 32, 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, B.; Li, F.; Kumar, P. Reverse furthest neighbors in spatial databases. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Engineering, Shanghai, China, 29 March–2 April 2009; pp. 664–675. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Gong, X.; Kong, D.; Hao, T.; Yan, X. A Voronoi-based group reverse k farthest neighbor query method in the obstacle space. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 50659–50673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Feng, J.; Fang, Q.; Ng, W. Two efficient hashing schemes for high-dimensional furthest neighbor search. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2017, 29, 2772–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Qin, L.; Zhang, W. I/O efficient algorithm for c-approximate furthest neighbor search in high dimensional space. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Database Systems for Advanced Applications, Jeju, Korea, 24–27 September 2020; pp. 221–236. [Google Scholar]

- Pagh, R.; Silvestri, F.; Sivertsen, J.; Skala, M. Approximate furthest neighbor in high dimensions. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Similarity Search and Applications, Glasgow, UK, 12–14 October 2015; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Cheema, M.A.; Lin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, D. Efficiently computing reverse k furthest neighbors. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Engineering, Helsinki, Finland, 16–20 May 2016; pp. 1110–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Q.; Feng, J.; Fang, Q. Reverse query-aware locality-sensitive hashing for high-dimensional furthest neighbor search. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Data Engineering, San Diego, CA, USA, 19–22 April 2017; pp. 167–170. [Google Scholar]

- Aly, A.M.; Aref, W.G.; Ouzzani, M. Spatial queries with two kNN predicates. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Very Large Data Bases, Istanbul, Turkey, 27–31 August 2012; pp. 1100–1111. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, Y.; Yu, G.; Yu, X. An efficient method for k nearest neighbor searching in obstructed spatial databases. J. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2014, 30, 1569–1583. [Google Scholar]

- Nutanong, S.; Zhang, R.; Tanin, E.; Kulik, L. Analysis and evaluation of V*-kNN: An efficient algorithm for moving kNN queries. VLDB J. 2010, 19, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, D.; Yiu, M.L.; Lo, E. A safe-exit approach for efficient network-based moving range queries. Data Knowl. Eng. 2012, 72, 126–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-J. Batch processing algorithm for moving k-farthest neighbor queries in road networks. In Proceedings of the KSCI Summer Conference 2021, Jeju, Korea, 15–17 July 2021; pp. 223–224. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.-J. Cluster nested Loop k-farthest neighbor join algorithm for spatial networks. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-J.; Attique, M. Group processing of multiple k-farthest neighbor queries in road networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 110959–110973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeywickrama, T.; Cheema, M.A.; Taniar, D. k-nearest neighbors on road networks: A journey in experimentation and in-memory implementation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Very Large Data Bases, New Delhi, India, 5–9 September 2016; pp. 492–503. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.C.K.; Lee, W.-C.; Zheng, B.; Tian, Y. ROAD: A new spatial object search framework for road networks. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2012, 24, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Li, G.; Tan, K.-L.; Zhou, L.; Gong, Z. G-tree: An efficient and scalable index for spatial search on road networks. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2015, 27, 2175–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, L.; Hua, W.; Zhou, X. Efficient batch processing of shortest path queries in road networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Mobile Data Management, Hong Kong, China, 10–13 June 2019; pp. 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Li, L.; Hua, W.; Zhou, X. Batch processing of shortest path queries in road networks. In Proceedings of the Australasian Database Conference on Databases Theory and Applications, Sydney, Australia, 29 January–1 February 2019; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, W.; Church, R.L. Finding shortest paths on real road networks: The case for A*. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2009, 23, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Datasets for Spatial Databases. Available online: https:/www.cs.utah.edu/~lifeifei/SpatialDataset.htm (accessed on 28 May 2022).

- Wu, L.; Xiao, X.; Deng, D.; Cong, G.; Zhu, A.D.; Zhou, S. Shortest path and distance queries on road networks: An experimental evaluation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Very Large Data Bases, Istanbul, Turkey, 27–31 August 2012; pp. 406–417. [Google Scholar]

- Bast, H.; Funke, S.; Matijevic, D. Ultrafast shortest-path queries via transit nodes. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Shortest Path Problem, Piscataway, NJ, USA, 13–14 November 2006; pp. 175–192. [Google Scholar]

| References | Space Domain | Query Type |

|---|---|---|

| [3,4,8,9,13] | Euclidean space | Reverse FN query |

| [1,4,10,11,12,14] | Euclidean space | FN query |

| [2] | Euclidean space | Aggregate FN query |

| [5,7] | Road network | Reverse FN query |

| [6] | Road network | Aggregate FN query |

| [20] | Road network | FN join query |

| [21] | Road network | Multiple FN query |

| This study | Road network | Moving FN query |

| Road Network | Description | Vertices | Edges | Vertex lists |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SJ | City streets in San Joaquin, California | 18,263 | 23,874 | 20,040 |

| NA | Highways in North America | 175,813 | 179,179 | 12,416 |

| SF | City streets in San Francisco, California | 174,956 | 223,001 | 192,276 |

| Parameter | Range |

|---|---|

| Number of query points () | 10 |

| Number of facilities () | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 () |

| Number of FNs required (k) | 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 |

| Query frequency in the query segment () | 2, 4, 8, 10, 20 |

| Distribution of facilities | Gaussian distribution |

| Number of centroids for the facilities in F () | 1, 3, 5, 7, 10 |

| Standard deviation for the normal distribution () | |

| Road network | SJ, NA, SF |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, H.-J. The Efficient Processing of Moving k-Farthest Neighbor Queries in Road Networks. Algorithms 2022, 15, 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/a15070223

Cho H-J. The Efficient Processing of Moving k-Farthest Neighbor Queries in Road Networks. Algorithms. 2022; 15(7):223. https://doi.org/10.3390/a15070223

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Hyung-Ju. 2022. "The Efficient Processing of Moving k-Farthest Neighbor Queries in Road Networks" Algorithms 15, no. 7: 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/a15070223

APA StyleCho, H.-J. (2022). The Efficient Processing of Moving k-Farthest Neighbor Queries in Road Networks. Algorithms, 15(7), 223. https://doi.org/10.3390/a15070223