Embedding Equality Constraints of Optimization Problems into a Quantum Annealer †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Problem Formulation

- (i)

- for each , ;

- (ii)

- for each , for some ( in this case).

- (C1)

- s.t. ,

- (C2)

- ,

- (C3)

- ,

3. Direct Approach

4. A Two-Level Approach

4.1. Gadgets

- Problem variables: variables in , i.e., variables used in the original constraint (2).

- Interface variables: variables in or used for interaction and exchange of information between neighboring cells by being located on the endpoints of an edge (coupler) joining the cells.

- Hidden variables: ancillary “working” variables in used to ensure that the given gadget/tile satisfies desired properties.

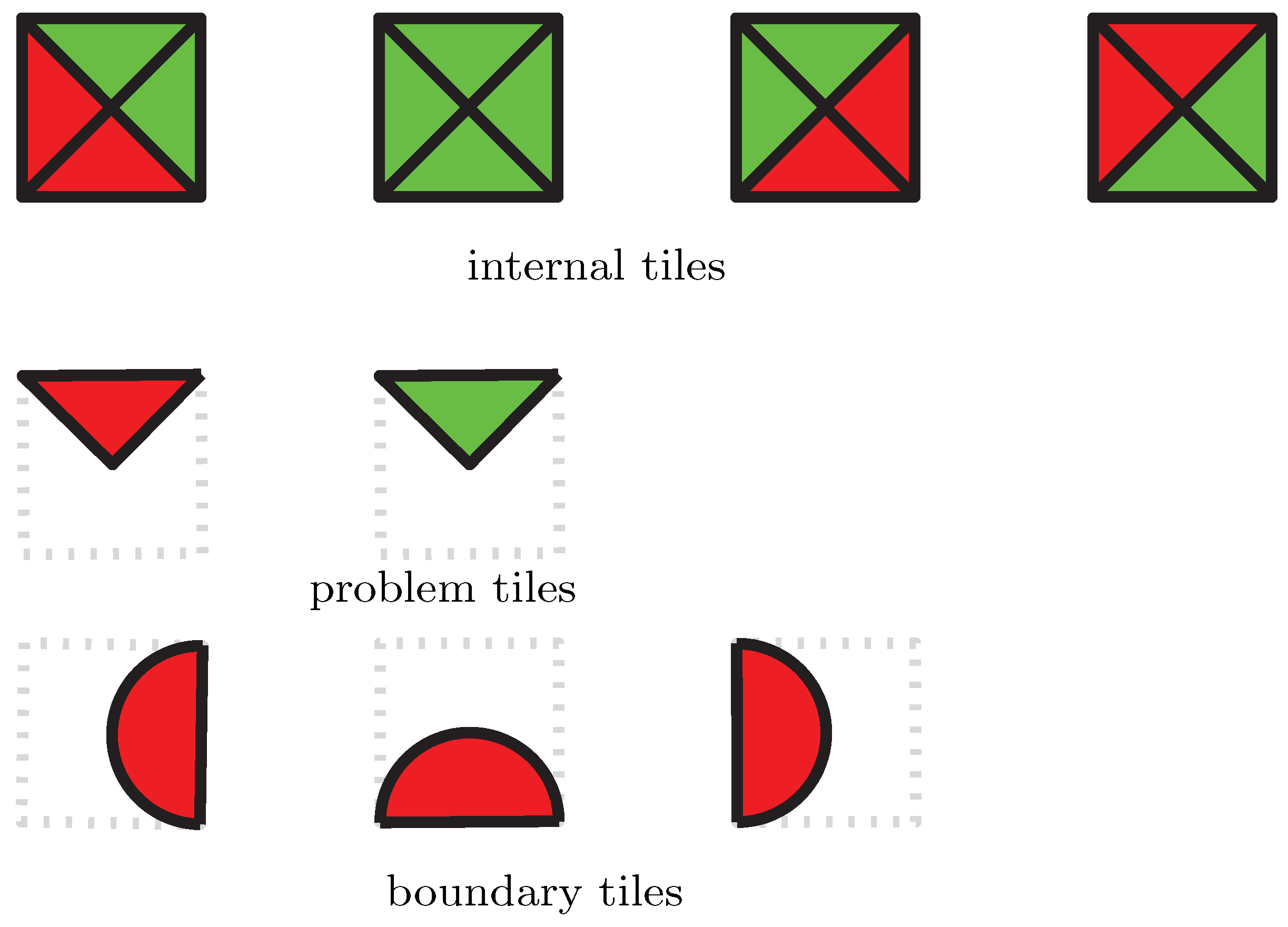

- Internal gadget—for cells in the interior of R and denoted by

;

- Problem gadget—containing a problem variable (and the only type that contains such a variable) and denoted by

;

- Boundary gadget—for cells on the boundary of the region R of the Chimera graph implementing the constraint. The three possible orientations of this gadget will be denoted by

,

, and

.

4.2. Tiles

.

.4.3. From Variables Assignments to Configurations of Tiles

5. Ising Program Design and Correctness Analysis

5.1. Cost of Tiles and Tile Configurations

5.2. Defining the Ising Program

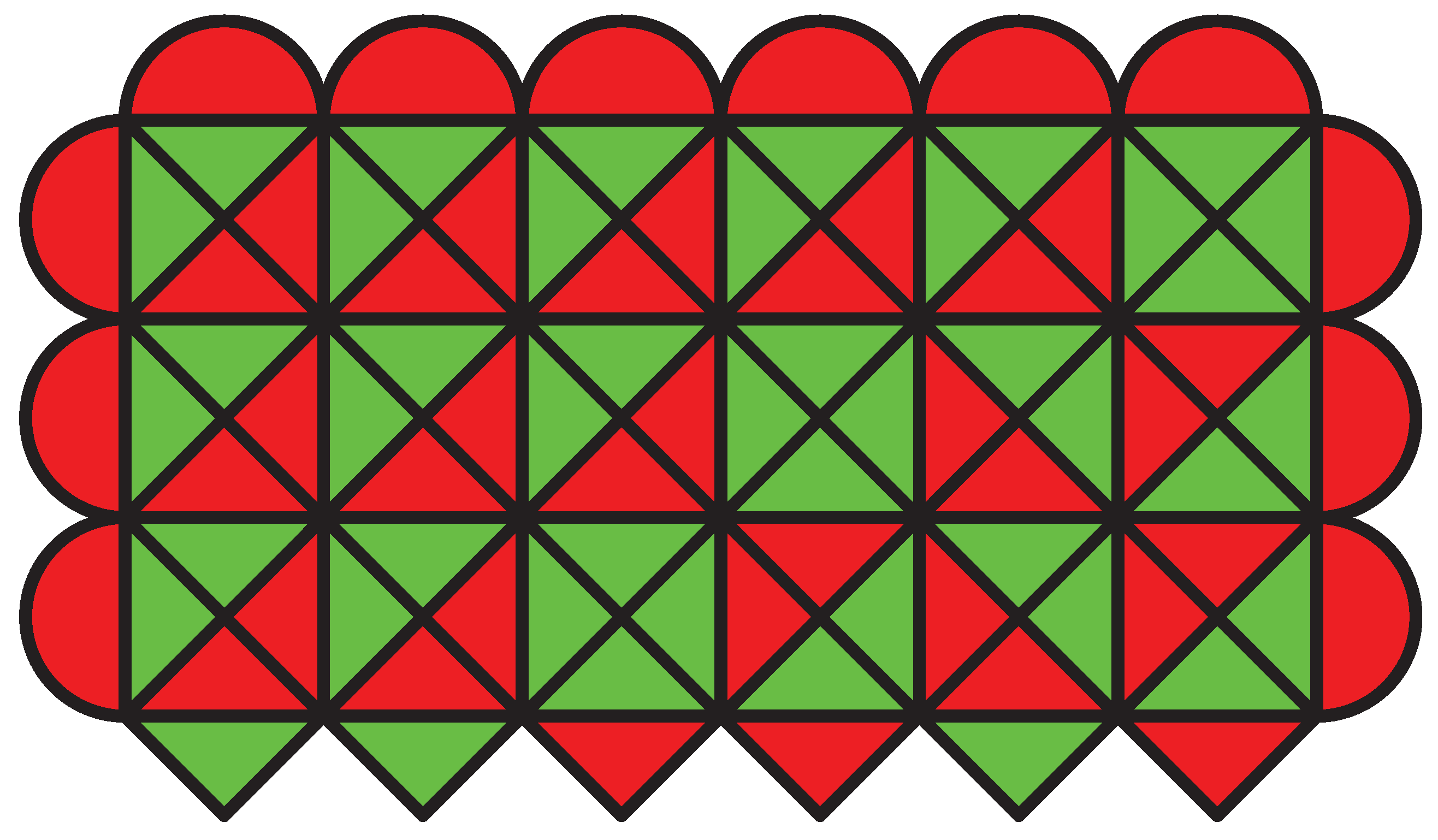

, to all rightmost cells we assign positive right boundary gadgets

, to all rightmost cells we assign positive right boundary gadgets  , and to all cells in the top row we assign positive top boundary gadgets

, and to all cells in the top row we assign positive top boundary gadgets  . To the rest (the bottom row), we assign problem gadgets

. To the rest (the bottom row), we assign problem gadgets  ; specifically, the i-th gadget is red, if , and green, if . The four corner cells are ignored (assigned zero coefficients). Coefficients corresponding to edges joining interface variables we set to 1, and the other coefficients we set to 0.

; specifically, the i-th gadget is red, if , and green, if . The four corner cells are ignored (assigned zero coefficients). Coefficients corresponding to edges joining interface variables we set to 1, and the other coefficients we set to 0. ḣas opposite sides in different colors.

ḣas opposite sides in different colors. , the leftmost and the rightmost sides are of different colors. This implies that since each row of R except the first and the last one has two red boundary tiles at its ends, i.e., tiles of the same color, we have the following.

, the leftmost and the rightmost sides are of different colors. This implies that since each row of R except the first and the last one has two red boundary tiles at its ends, i.e., tiles of the same color, we have the following. .

. in . Let be the first such tile. Hence, there is no

in . Let be the first such tile. Hence, there is no  tile in and, by Proposition 1, for . Since is

tile in and, by Proposition 1, for . Since is  , is green and is red. For the remaining tiles we can see that if tile is red for , then is

, is green and is red. For the remaining tiles we can see that if tile is red for , then is  , otherwise is

, otherwise is  . In both cases, . In summary, for and is red, while is green, which proves the lemma. ☐

. In both cases, . In summary, for and is red, while is green, which proves the lemma. ☐ , to be

, to be  , and for to be

, and for to be  if is red and

if is red and  , otherwise.

, otherwise. in , contradicting Proposition 2. Hence there is no optimal tiling in that case. ☐

in , contradicting Proposition 2. Hence there is no optimal tiling in that case. ☐ , which tile is required in by Proposition 2 in any optimal tiling. Hence, there is no optimal tiling of R if . ☐

, which tile is required in by Proposition 2 in any optimal tiling. Hence, there is no optimal tiling of R if . ☐6. Solving the Optimization Problem

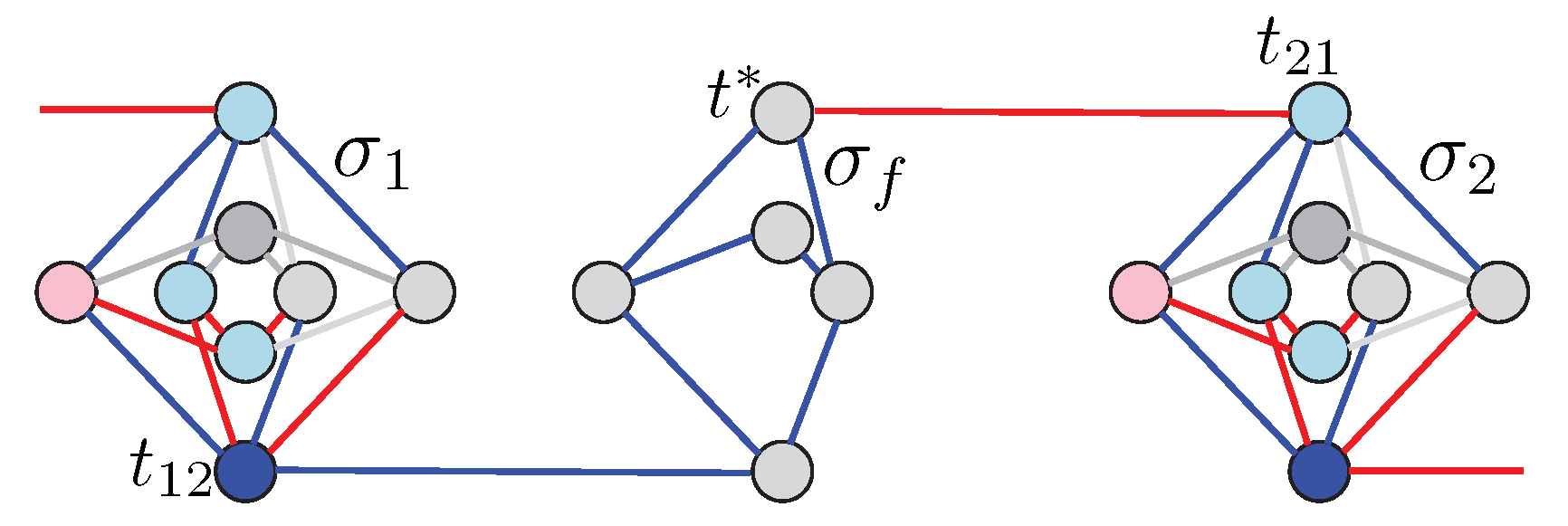

since it is the most interesting. For this gadget, we have 4 good tiles

since it is the most interesting. For this gadget, we have 4 good tiles  ,

,  ,

,  , and

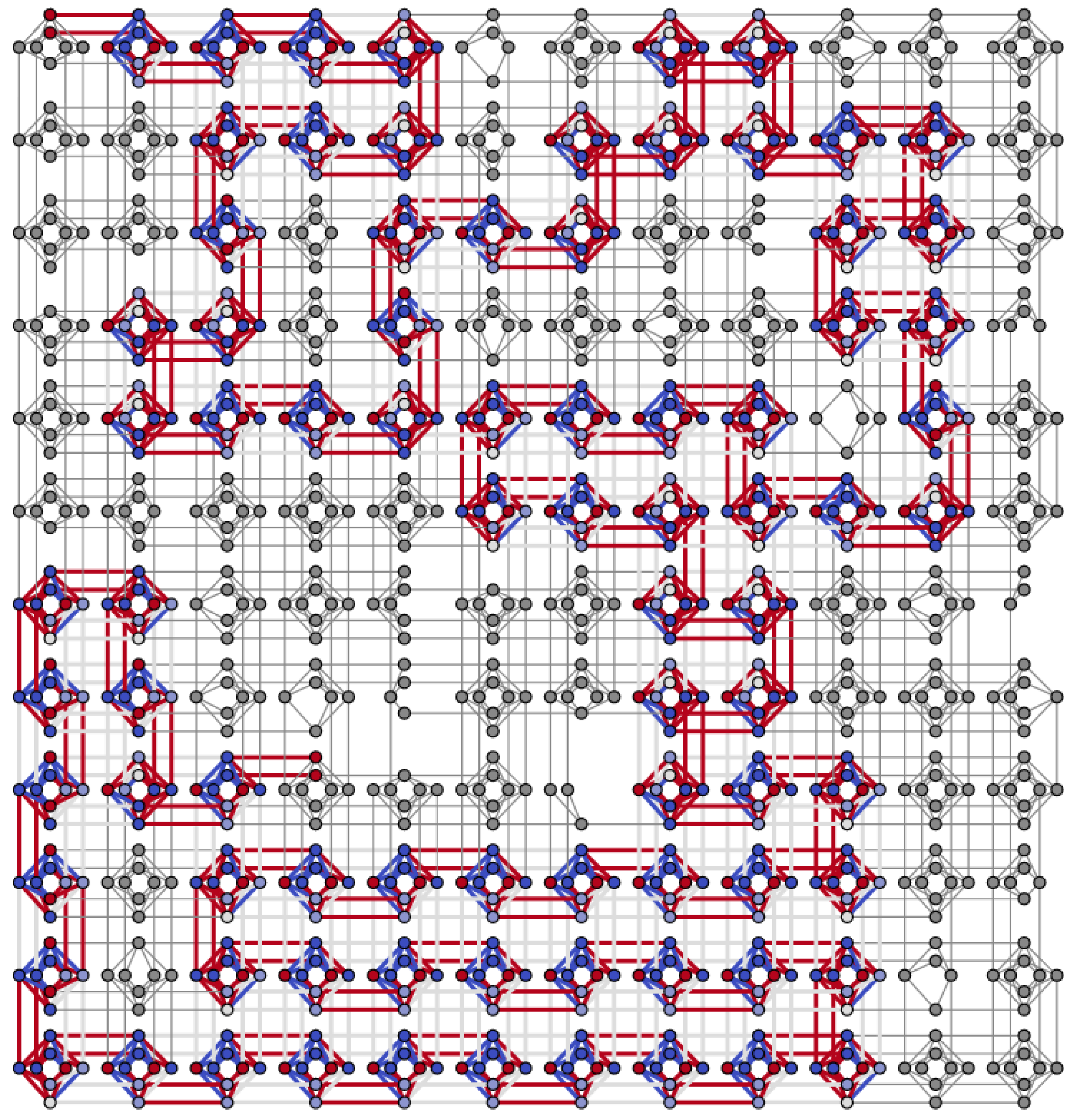

, and  , and all others are bad tiles. Denote this Ising program by and its coefficients by (since internal gadgets do not have variables, their coefficients in front of the and terms are zeros). Define sets of all 4-tuples of interface variables of good internal tiles (see Figure 2) and of all remaining 4-tuples. Then we formulate the following optimization problem.

, and all others are bad tiles. Denote this Ising program by and its coefficients by (since internal gadgets do not have variables, their coefficients in front of the and terms are zeros). Define sets of all 4-tuples of interface variables of good internal tiles (see Figure 2) and of all remaining 4-tuples. Then we formulate the following optimization problem.- (C1)

- For all s.t. ,

- (C2)

- For all ,

- (C3)

- For all

7. Improved Embeddings for the Case

7.1. Reducing the Number of Cells

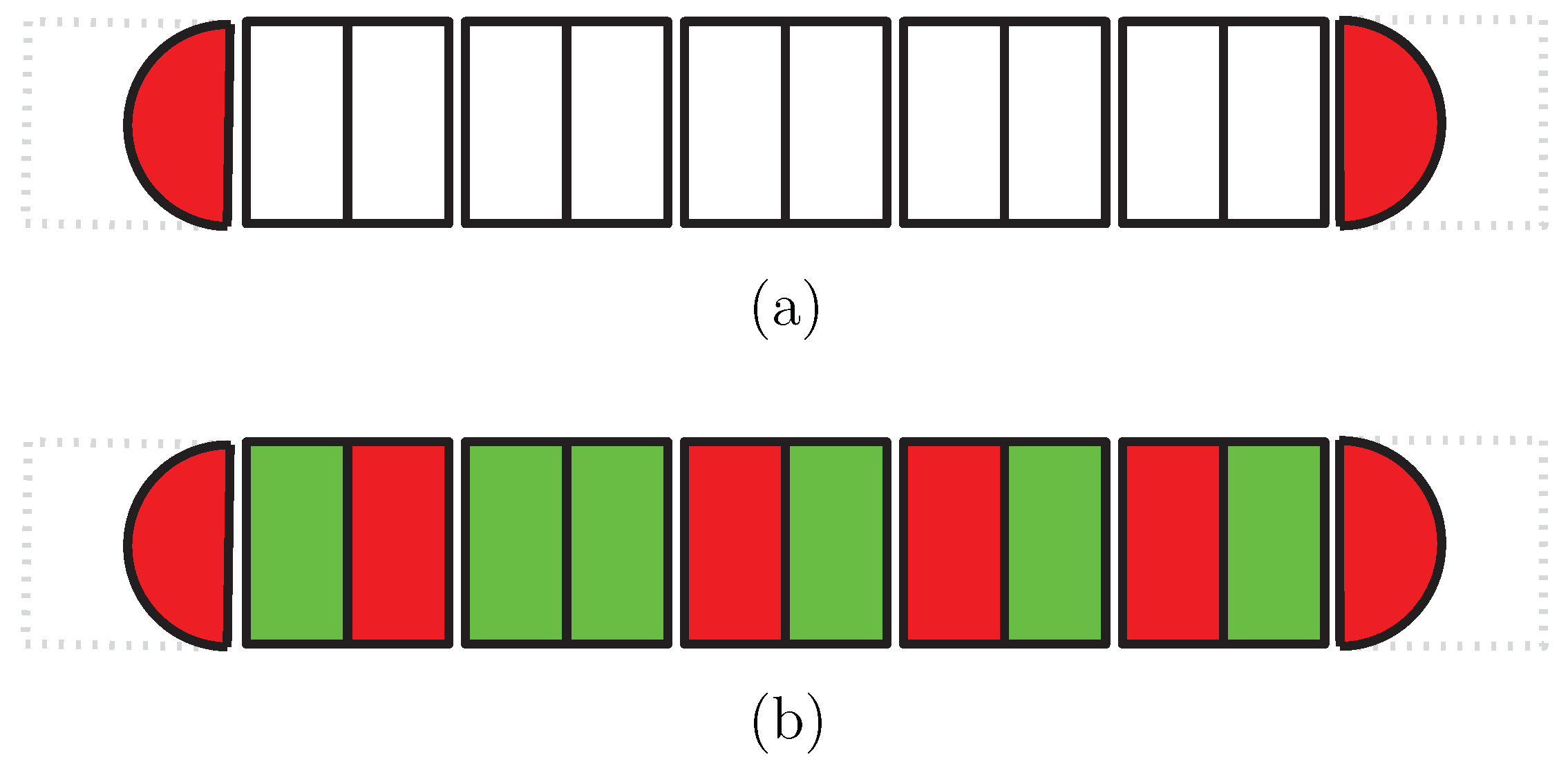

- An internal gadget—for cells in the interior of the row, and will be denoted by

. Each internal gadget contains one problem, two interface, and five hidden variables (Figure 7a,b).

- A boundary gadget—for cells on the two ends of the row. They are similar to the boundary gadgets in the general case, but come in only two orientations, which will be denoted by

and

.

tile has value of the x variable set to 1 and the other two good tiles hold an x variable set to .

tile has value of the x variable set to 1 and the other two good tiles hold an x variable set to . tile. To estimate the value of , we state the following analogues of Propositions 1 and 2.

tile. To estimate the value of , we state the following analogues of Propositions 1 and 2. ḣas left and right sides in different colors.

ḣas left and right sides in different colors. tile.

tile. . On position , we should have a tile with a left side colored in red, which cn be either a

. On position , we should have a tile with a left side colored in red, which cn be either a  or a

or a  tile. In the former case, the

tile. In the former case, the  tile on the i-th position is the last internal tile from the left, so it is the only

tile on the i-th position is the last internal tile from the left, so it is the only  tile. In the latter case, a

tile. In the latter case, a  tile has a right side in green, so it can be followed by either a

tile has a right side in green, so it can be followed by either a  or a

or a  tile. By induction, it follows that the first

tile. By induction, it follows that the first  tile is followed by

tile is followed by  tiles and a

tiles and a  tile. Hence we have the following analogue of Lemma 1.

tile. Hence we have the following analogue of Lemma 1.7.2. Increasing the Size of the Constraint

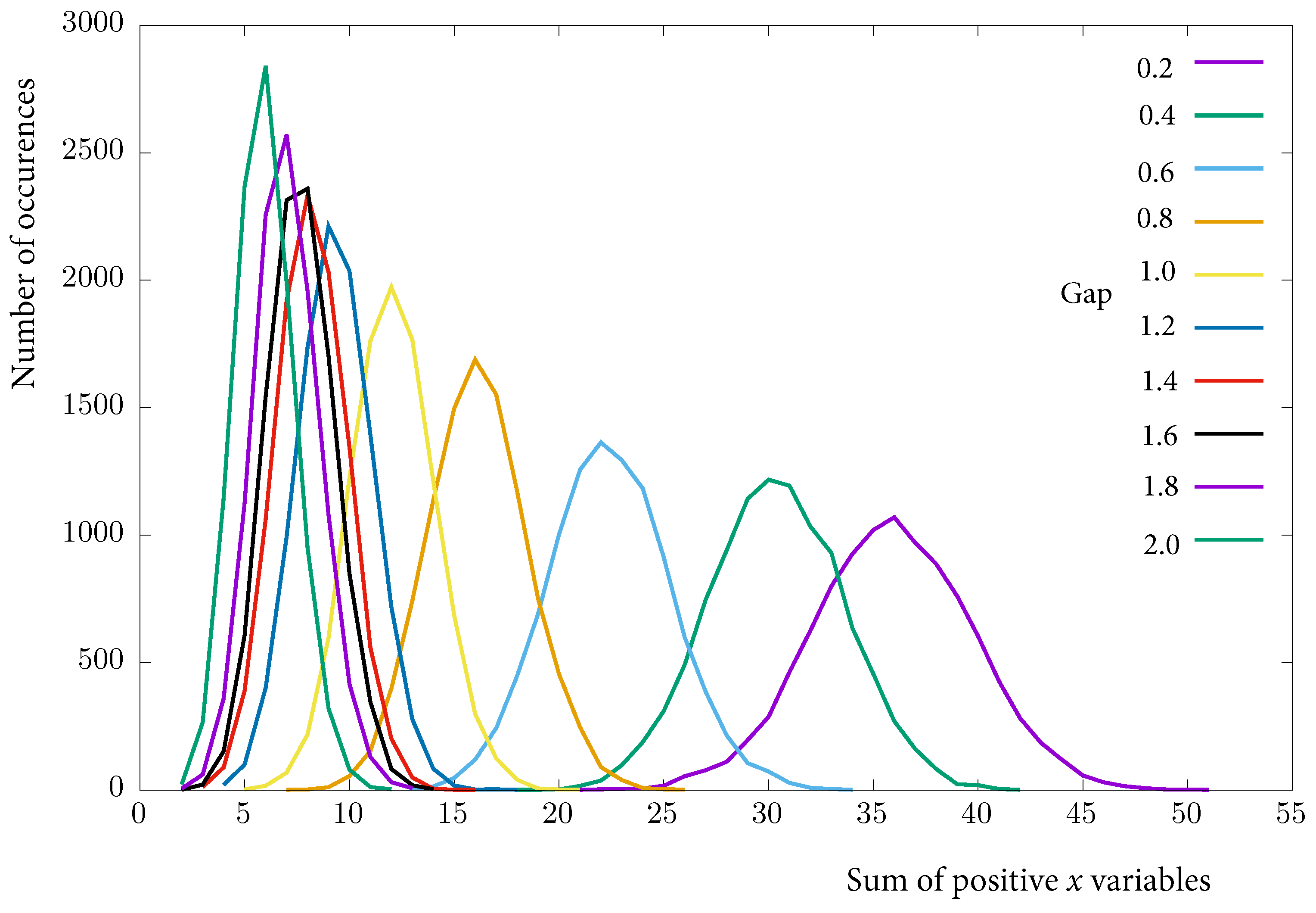

7.3. Increasing the Gap

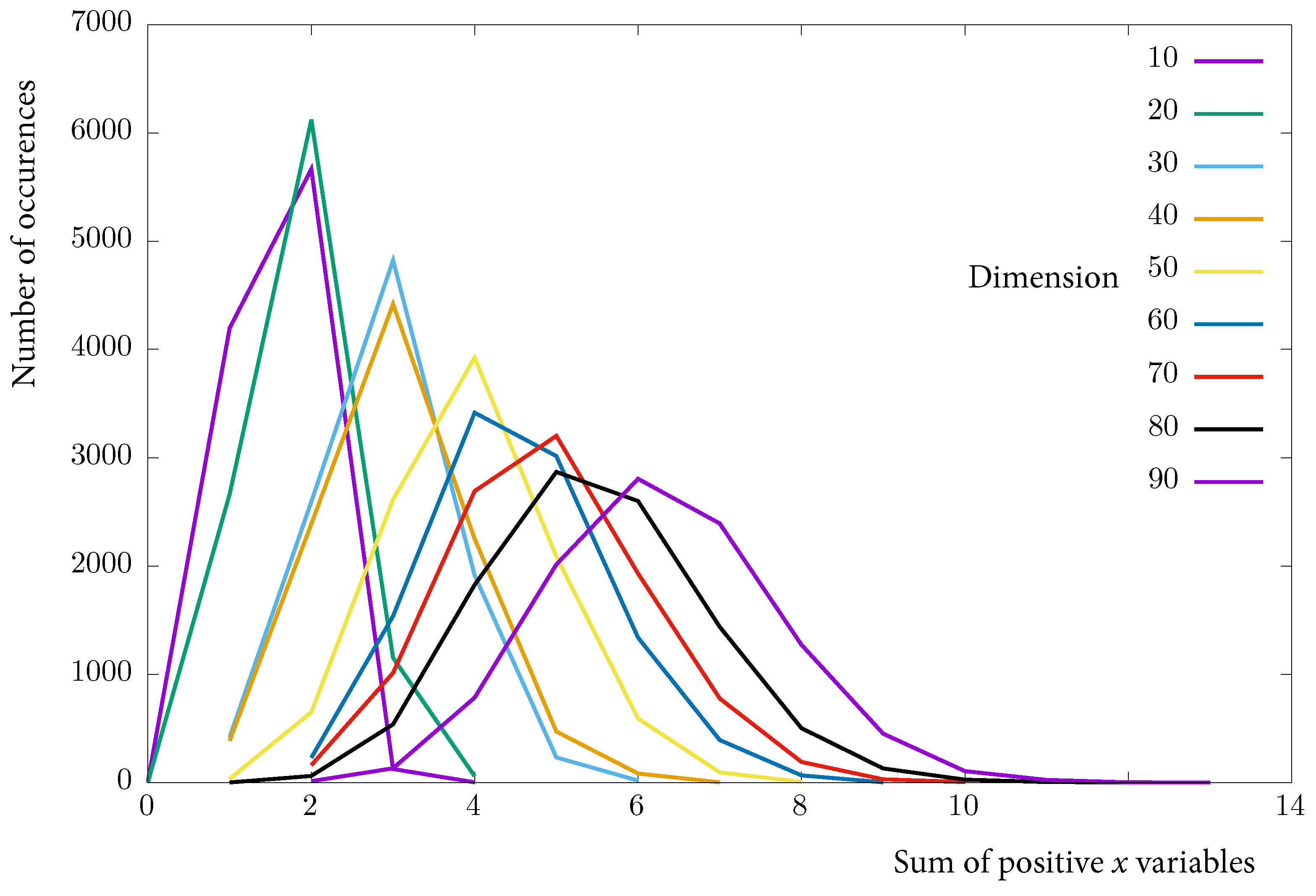

8. Experiments

8.1. Multi-Row Algorithm

8.1.1. Embedding in the Real Chimera Graph

8.1.2. Analysis

8.2. Increased-Gap Algorithm

8.2.1. Modifying the Embedding for the Real Chimera Graph

8.2.2. Results

9. Using the Constraint Embeddings for Solving Constrained Optimization Problems

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garey, M.R.; Johnson, D.S. Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness; W. H. Freeman & Co.: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sahni, S. Computationally Related Problems. SIAM J. Comput. 1974, 3, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Amin, M.; Gildert, S.; Lanting, T.; Hamze, F.; Dickson, N.; Harris, R.; Berkley, A.; Johansson, J.; Bunyk, P.; et al. Quantum annealing with manufactured spins. Nature 2011, 473, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunyk, P.; Hoskinson, E.; Johnson, M.; Tolkacheva, E.; Altomare, F.; Berkley, A.; Harris, R.; Hilton, J.; Lanting, T.; Przybysz, A.; et al. Architectural Considerations in the Design of a Superconducting Quantum Annealing Processor. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2014, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, A. Ising formulations of many NP problems. Front. Phys. 2014, 2, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichot, C.; Siarry, P. Graph Partitioning; Wiley-IST: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bian, Z.; Chudak, F.; Israel, R.; Lackey, B.; Macready, W.G.; Roy, A. Discrete optimization using quantum annealing on sparse Ising models. Front. Phys. 2014, 2, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimatti, A.; Griggio, A.; Schaafsma, B.J.; Sebastiani, R. The MathSAT5 SMT Solver. In Tools and Algorithms for the Construction and Analysis of Systems; Piterman, N., Smolka, S.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 93–107. [Google Scholar]

- De Moura, L.; Bjørner, N. Satisfiability Modulo Theories: Introduction and Applications. Commun. ACM 2011, 54, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsekas, D. Nonlinear Programming; Athena Scientific: Nashua, NH, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Auslender, A.; Cominetti, R.; Haddou, M. Asymptotic Analysis for Penalty and Barrier Methods in Convex and Linear Programming. Math. Oper. Res. 1997, 22, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birgin, E.; Martínez, J. Practical Augmented Lagrangian Methods for Constrained Optimization; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, E.K.P.; Zak, S.H. Algorithms for Constrained Optimization. In An Introduction to Optimization; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011; Chapter 22; pp. 513–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kochenberger, G.; Hao, J.K.; Glover, F.; Lewis, M.; Lü, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y. The Unconstrained Binary Quadratic Programming Problem: A Survey. J. Comb. Optim. 2014, 28, 58–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, V. Minor-embedding in adiabatic quantum computation: I. The parameter setting problem. Quantum Inf. Process. 2008, 7, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, V. Different adiabatic quantum optimization algorithms. Quantum Inf. Comput. 2011, 11, 638–648. [Google Scholar]

- Klymko, C.; Sullivan, B.D.; Humble, T.S. Adiabatic quantum programming: Minor embedding with hard faults. Quantum Inf. Process. 2014, 13, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boothby, T.; King, A.; Roy, A. Fast clique minor generation in Chimera qubit connectivity graphs. Quantum Inf. Process. 2016, 15, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Macready, W.G.; Roy, A. A practical heuristic for finding graph minors. arXiv, 2014; arXiv:1406.2741. [Google Scholar]

- Rieffel, E.G.; Venturelli, D.; O’Gorman, B.; Do, M.; Prystay, E.M.; Smelyanskiy, V. A case study in programming a quantum annealer for hard operational planning problems. Quantum Inf. Process. 2015, 14, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Z.; Chudak, F.; Israel, R.B.; Lackey, B.; Macready, W.G.; Roy, A. Mapping Constrained Optimization Problems to Quantum Annealing with Application to Fault Diagnosis. Front. ICT 2016, 3, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, K.E.; Humble, T.S. Identifying the minor set cover of dense connected bipartite graphs via random matching edge sets. Quantum Inf. Process. 2017, 16, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrich, T.D.; Sullivan, B.D.; Humble, T.S. Optimizing adiabatic quantum program compilation using a graph-theoretic framework. Quantum Inf. Process. 2018, 17, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Date, P.; Patton, R.; Schuman, C.; Potok, T. Efficiently embedding QUBO problems on adiabatic quantum computers. Quantum Inf. Process. 2019, 18, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyskocil, T.; Djidjev, H. Simple constraint embedding for quantum annealers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Rebooting Computing, Tysons, VA, USA, 7–9 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vyskocil, T.; Pakin, S.; Djidjev, H. Embedding Inequality Constraints for Quantum Annealing Optimization; Technical Report LA-UR-18-3097; Los Alamos National Laboratory: Alamos, NM, USA, 2018.

- Fourer, R.; Gay, D.M.; Kernighan, B.W. AMPL: A Modelling Language for Mathematical Programming, 2nd ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gurobi Optimizer Reference Manual; Gurobi Optimization, Inc.: Beaverton, OR, USA, 2015.

- Technical Description of the D-Wave Quantum Processing Unit; 09-1109A-A; D-Wave: Burnaby, BC, Canada, 2016.

) and problem (

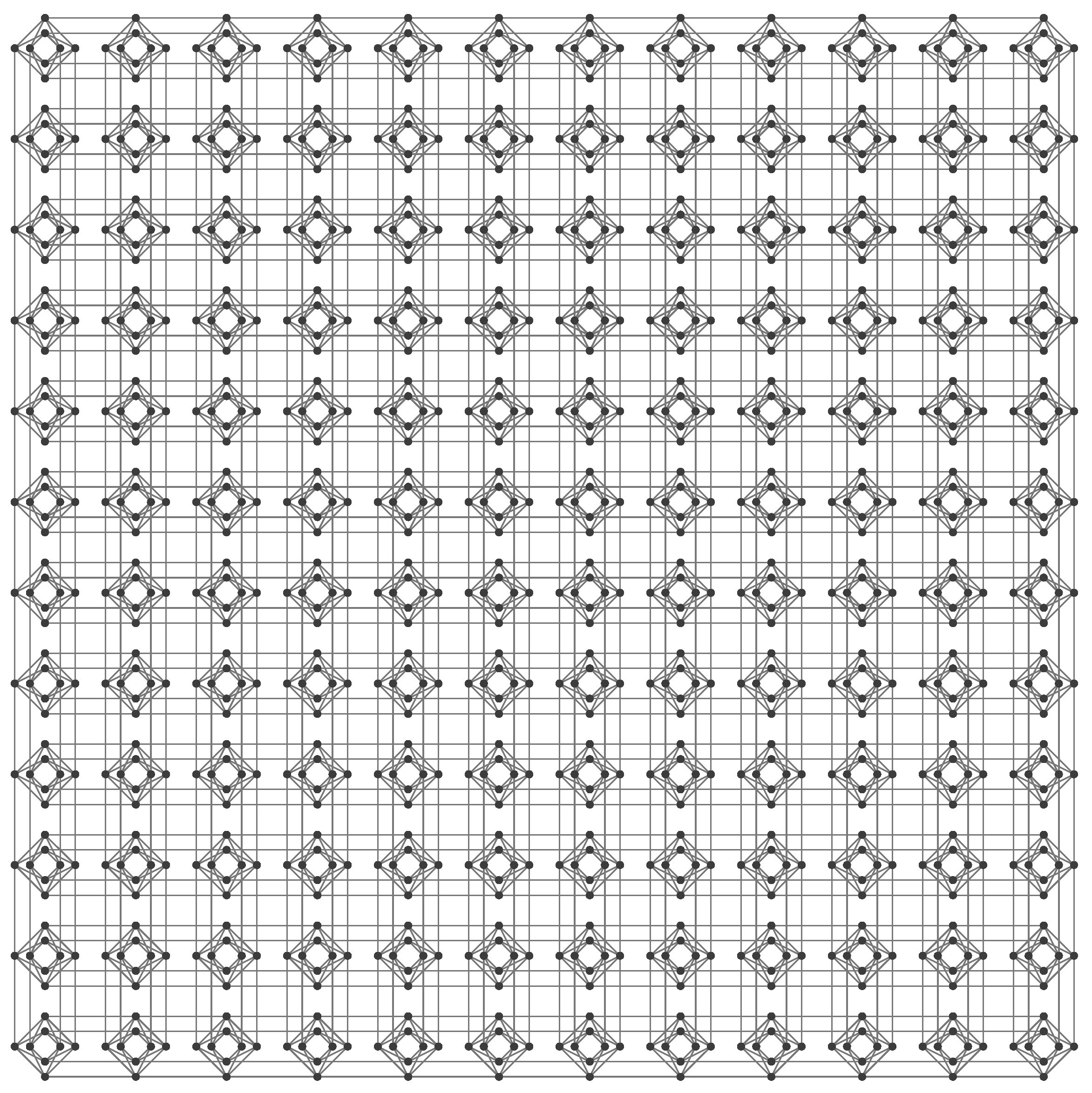

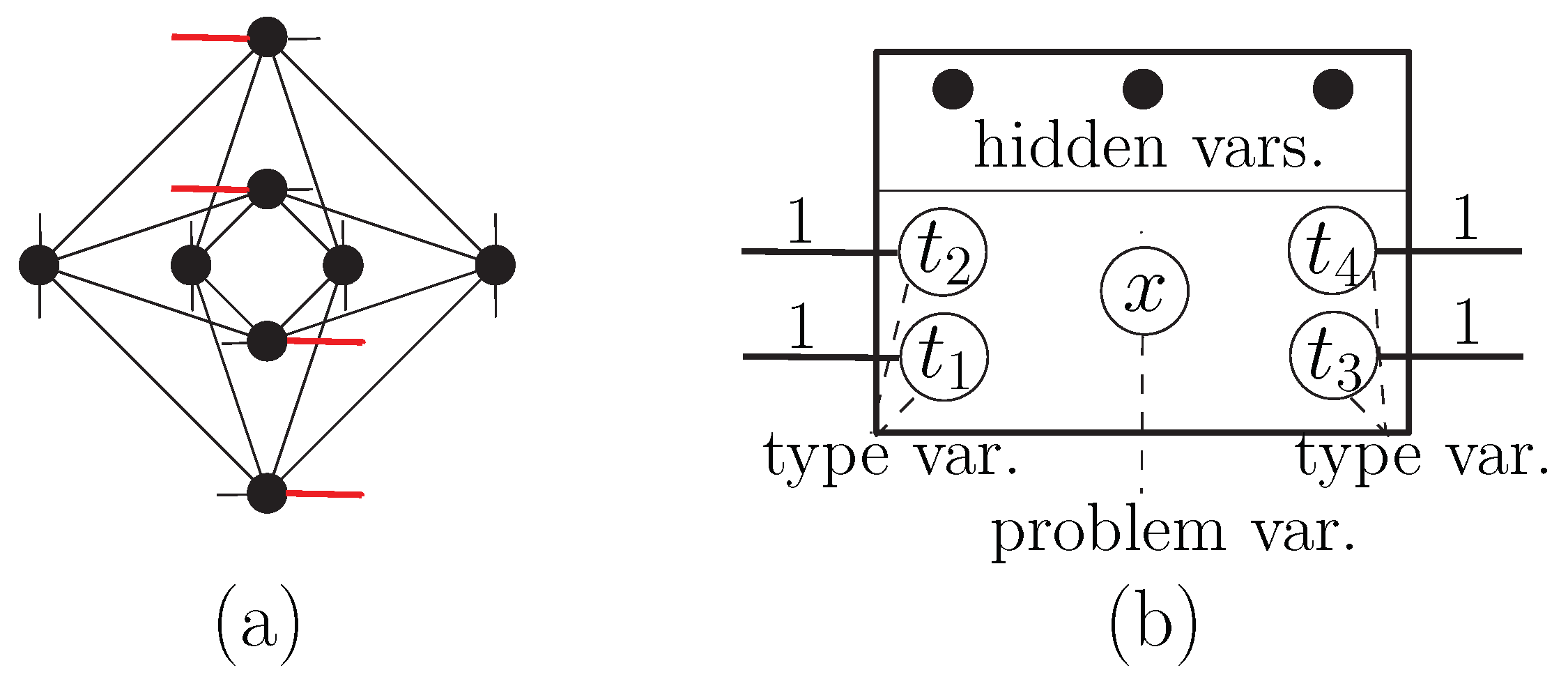

) and problem ( ) type gadgets and tiles. (a) A cell of the Chimera graph. Short lines denote couplers connecting the cell to other cells. (b) The logical structure of the corresponding internal gadget, showing the types of the variables, and, as an example, a concrete assignment of values to the interface variables. (c) The corresponding tile as used in our embedding illustrations, with red color for +1 and green for −1 type variables. Analogous illustrations for the problem type gadget and tile are found in (d–f).

) type gadgets and tiles. (a) A cell of the Chimera graph. Short lines denote couplers connecting the cell to other cells. (b) The logical structure of the corresponding internal gadget, showing the types of the variables, and, as an example, a concrete assignment of values to the interface variables. (c) The corresponding tile as used in our embedding illustrations, with red color for +1 and green for −1 type variables. Analogous illustrations for the problem type gadget and tile are found in (d–f).

) and problem (

) and problem ( ) type gadgets and tiles. (a) A cell of the Chimera graph. Short lines denote couplers connecting the cell to other cells. (b) The logical structure of the corresponding internal gadget, showing the types of the variables, and, as an example, a concrete assignment of values to the interface variables. (c) The corresponding tile as used in our embedding illustrations, with red color for +1 and green for −1 type variables. Analogous illustrations for the problem type gadget and tile are found in (d–f).

) type gadgets and tiles. (a) A cell of the Chimera graph. Short lines denote couplers connecting the cell to other cells. (b) The logical structure of the corresponding internal gadget, showing the types of the variables, and, as an example, a concrete assignment of values to the interface variables. (c) The corresponding tile as used in our embedding illustrations, with red color for +1 and green for −1 type variables. Analogous illustrations for the problem type gadget and tile are found in (d–f).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vyskocil, T.; Djidjev, H. Embedding Equality Constraints of Optimization Problems into a Quantum Annealer. Algorithms 2019, 12, 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/a12040077

Vyskocil T, Djidjev H. Embedding Equality Constraints of Optimization Problems into a Quantum Annealer. Algorithms. 2019; 12(4):77. https://doi.org/10.3390/a12040077

Chicago/Turabian StyleVyskocil, Tomas, and Hristo Djidjev. 2019. "Embedding Equality Constraints of Optimization Problems into a Quantum Annealer" Algorithms 12, no. 4: 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/a12040077

APA StyleVyskocil, T., & Djidjev, H. (2019). Embedding Equality Constraints of Optimization Problems into a Quantum Annealer. Algorithms, 12(4), 77. https://doi.org/10.3390/a12040077