2.1. Description of the Model

For unidirectional fiber structures, the thermal conductivity parallel to the fiber direction is considered to be well described by the rule of mixtures, while the situation in the transverse direction is more complicated. Thus, the purpose of this section is to develop an analytical model to relate the transverse thermal conductivity of these structures to the ones of their four components (fiber, interfacial layer, matrix and pore).

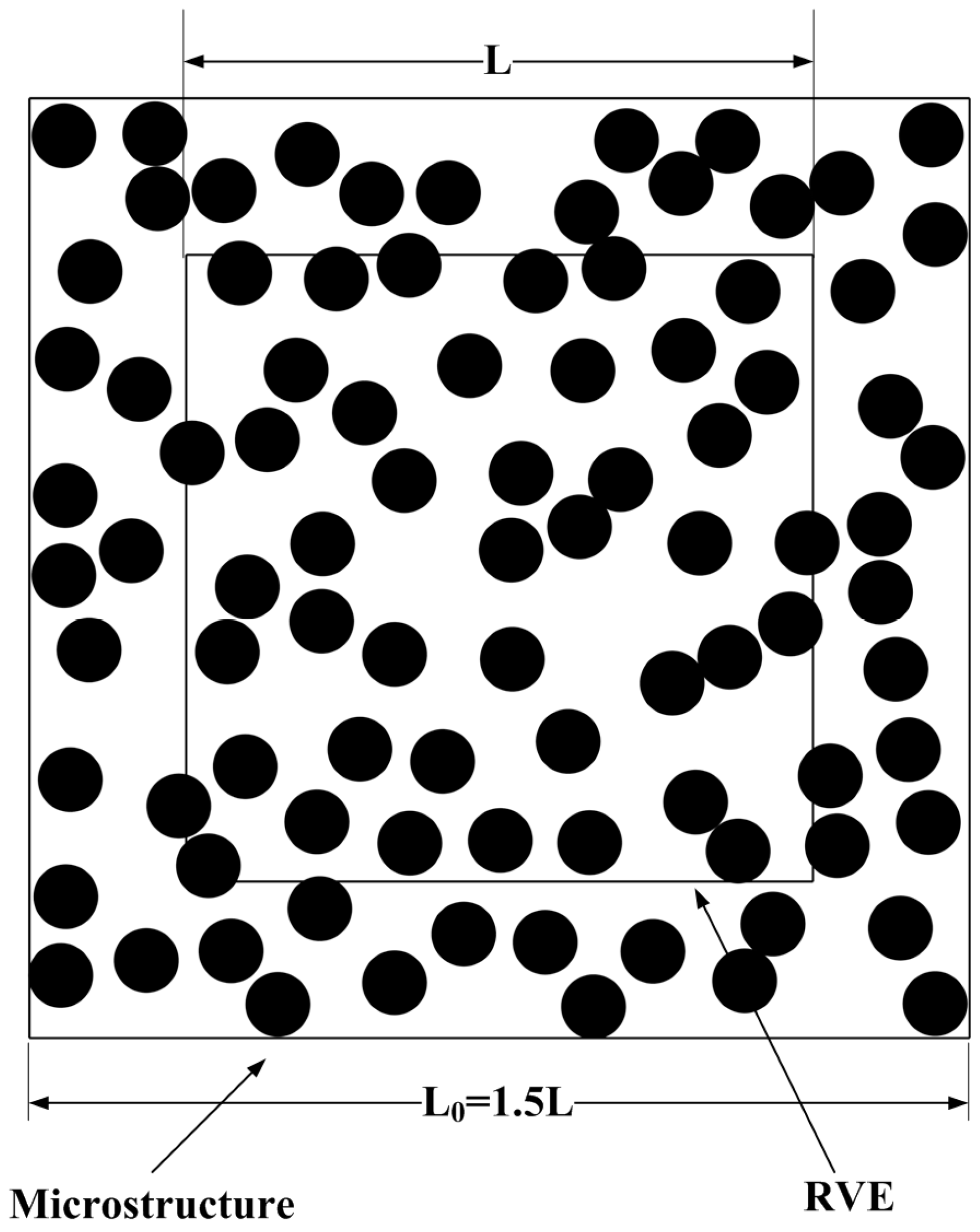

To investigate the fiber distribution effects on transverse thermal conductivity of fiber-reinforced composites, the microstructure with random fiber distribution can be generated using a program developed in MATLAB. Specifically, the procedure starts with a specified microstructure with square cross-section and proceeds by randomly and sequentially adding the circular fiber inside the microstructure. Each added fiber is accepted and its position is recorded only if it does not overlap with any of the ones previously accepted. For high fiber volume fraction, a small amount of overlapping is allowable. In addition, the boundaries of the microstructure act like rigid walls; thus, no fibers pass through the boundaries, and all fibers are restricted inside the microstructure. The microstructures generated in this manner are primarily governed by the choice of porosity

p and the allowable inter-fiber distance

dmin. The former is calculated as

, where

Nf is the number of included fibers,

rf is the fiber radius, and

L0 is the length of the microstructure. The latter (

dmin) is defined such that the shortest allowable distance between the centers of two fibers is larger than (2 +

dmin)

rf. The selection values of

dmin are 0.1 or 0 in this study. For the case of heat transfer transverse to the axis of randomly distributed fibers, the representative volume element (RVE) may be simulated by a square window placed on the cross section of the microstructure with the following relative scale dimensions:

L0 = 1.5

L, where

L is the length of the RVE (as depicted in

Figure 1). In addition, to assure the RVE contains a statistical representation of all local heterogeneities, the relative RVE size with respect to the scale of microstructural dimensions should be sufficiently large. The study of the scale effects indicates that the estimated thermal conductivities (as averaged over three independent simulation runs) are almost constant when the REV size is larger than 50

rf, thus the sizes of RVE are set as 50

rf × 50

rf in this study.

To characterize the isotropy of the simulated fiber structures, we consider there are

N fibers located less than distance

R apart from the center of the microstructure, where

R = 50

rf in this study, and introduce the anisotropy parameter (

):

where

is the orientation angle (with respect to the positive x coordinate) of the line connecting the center of the unit cell and the

ith fiber. The values of

is +1 or −1 when all fibers are distributed along the x-axis or along the y-axis. When fibers structure is isotropic,

approaches zero. The absolute values of

were found typically less than 0.01 for all simulated fiber structures, which we consider to satisfy the isotropy requirement.

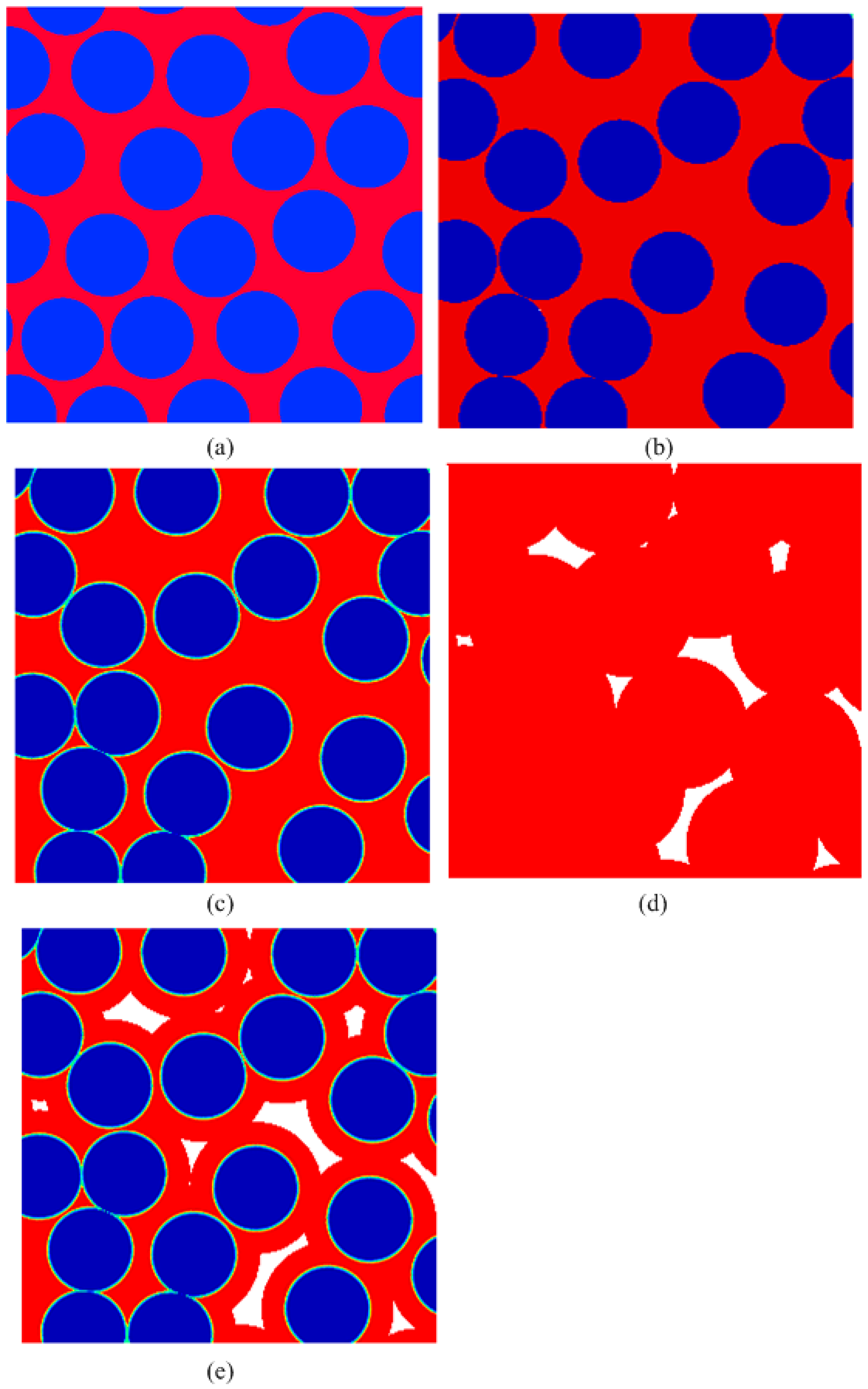

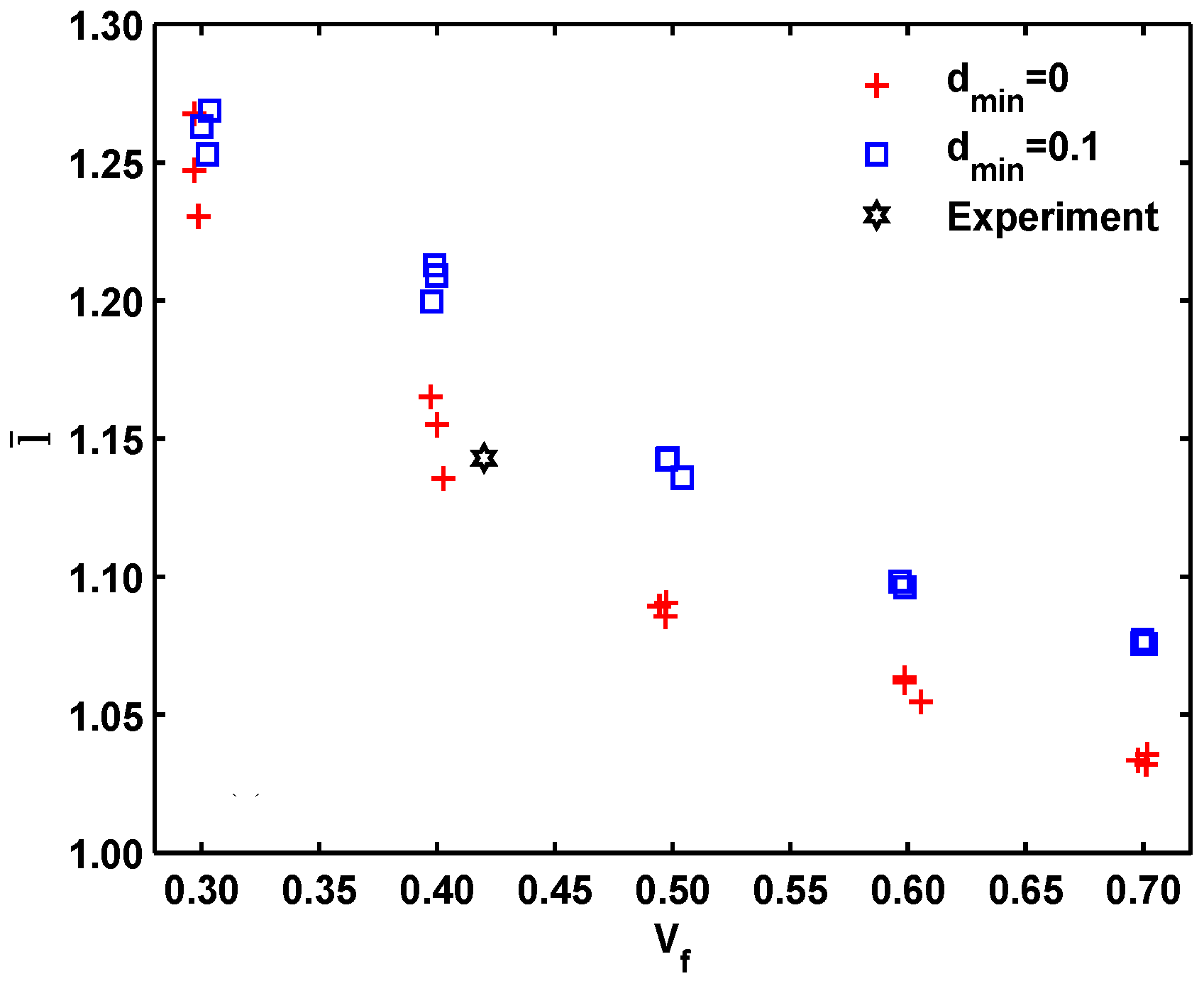

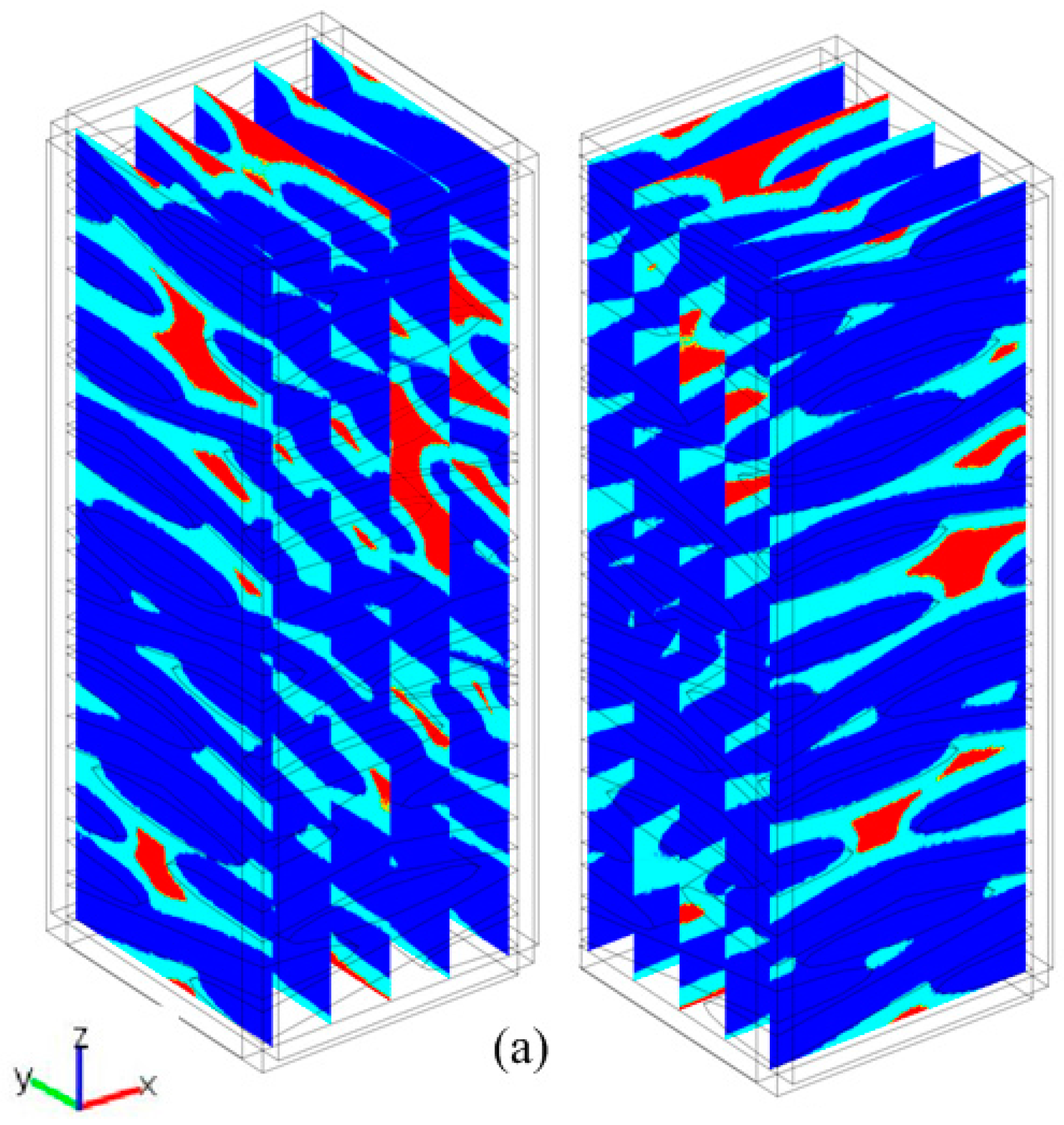

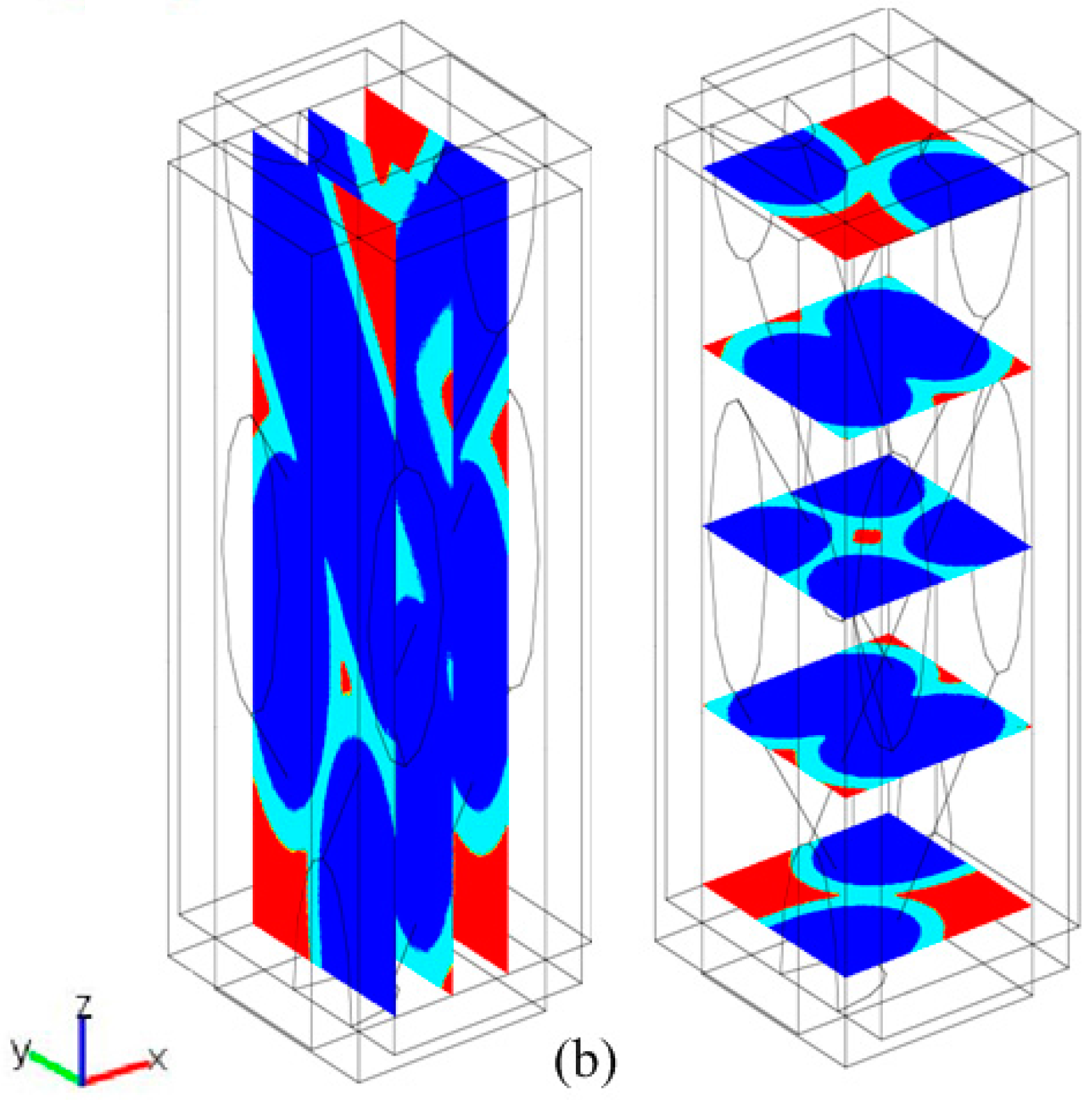

The resultant microstructures are shown in

Figure 2a,b. It can be observed that the generated fiber structures have different degree of local non-uniformity, although all of them are statistically homogenous. Thus, prior to any analysis, it is necessary to quantify the microstructure of the fiber distribution. In this effort, the normalized average nearest inter-fiber distance,

, whose statistics differ between different fiber distributions, is introduced to characterize the degree of the non-uniformity.

is defined as

where

Li is the nearest distance between the

ith fiber and its neighbor,

ri is the radius of the

ith fiber and

rinearest is the radius of the fiber which is nearest to the

ith fiber. Given the same fiber volume, small values of

are associated with heterogeneous patterns, while large values of

indicate homogeneous patterns, and its variation can be seen as a measure of the fiber dispersion. In

Figure 3, the data for two fiber structures are compared with Spitzig’s experimental measurement [

23]. We can observe that, Spitzig’s experimental data is consistent with our data for the simulated fiber structure with

dmin = 0, hence only the thermal conductivities of the simulated fiber structure with

dmin = 0 are chosen as the research subject.

By adopting the locations of the fibers and increasing the radius of the circles, the material systems with different phase have been developed and shown in

Figure 2b–e. Appling the corresponding temperature and thermal insulation boundaries to the unit cells, the transverse thermal conductivity of these material systems can be calculated using finite element software “COMSOL Multiphysics” coupled with MATLAB. Then the effect of all constituent (fiber, interfacial layer, matrix and pore) thermal conductivities on the global thermal transport properties of the material systems can be studied. The full solving details can be found in Reference [

24].

2.2. The Analytical Model

In 1892, Rayleigh [

25] investigated the conductivity of an uniform medium composed of cylindrical obstacles (fibers) arranged in rectangular order, applied two boundary conditions (radial heat flux and temperature potential continuity) at the fiber/matrix interface and solved the steady-state heat conduction (mathematically the potential equation) to give approximate function to predict transverse ETC [

26,

27]:

where

B is a dimensionless variable defined as

where

Vf,

,

Km,

and

k are the volume fraction of fiber, the transverse thermal conductivity of the one-dimensional composite, the thermal conductivity of the isotropic matrix, the transverse thermal conductivity of isotropic fiber and the fiber-to-matrix conductivity ratio, respectively. When the fiber volume fraction is low, the higher order terms of Equation (3) can be ignored, then Rayleigh’s model reduces to the so called self-consistent formula [

28]:

Another famous model is developed by Hasselman and Johnson [

29], who considered the imperfect interface between fibers and matrix and introduced an effective interfacial conductance

Hi, their model is expressed as:

where

rf is the fiber radius. If we introduced an interfacial Biot number,

Bi (

) and Equation (5) into Hasselman and Johnson’s model, then H-J model can be easily rearranged into the following form:

Comparing Equation (6) with (8), it is clearly found that the self-consistent model is just the special case of H-J model when 1/

Bi→0, the composites with imperfect fiber/matrix interface can be practically seen as the ones with perfect conductance, in which the effect of imperfect interface is lumped into fiber-to-matrix conductivity ratio

k. Typical to the cylindrically orthotropic carbon fibers-reinforced composites, Later, Hasselman [

30] used the same method to develop the following formula to estimate the transverse thermal conductivity:

where

Kθ and

Kr are the radial and tangential thermal conductivity of the cylindrically orthotropic fiber, respectively. Obviously, Equation (9) agrees to Equation (7) if

.

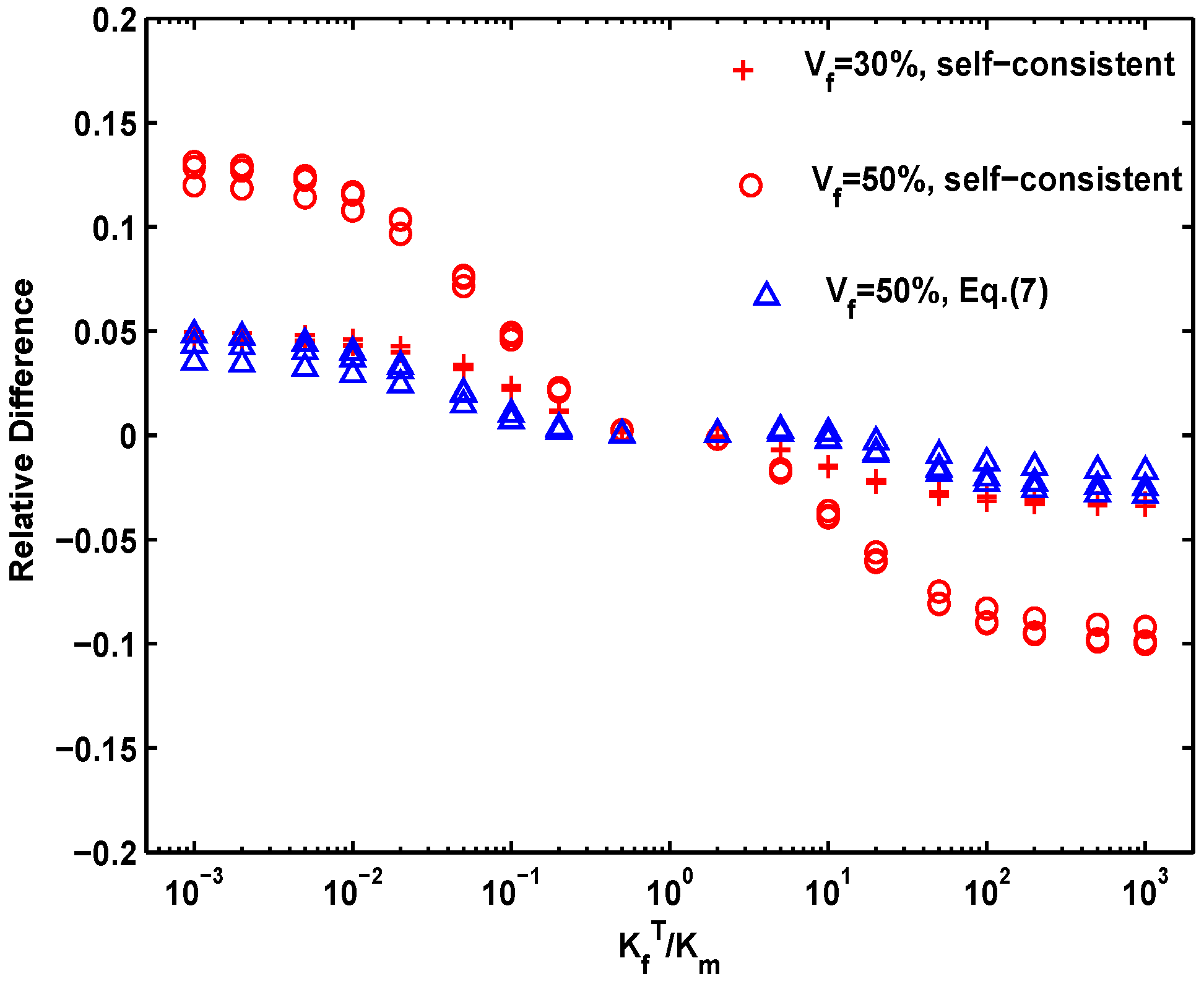

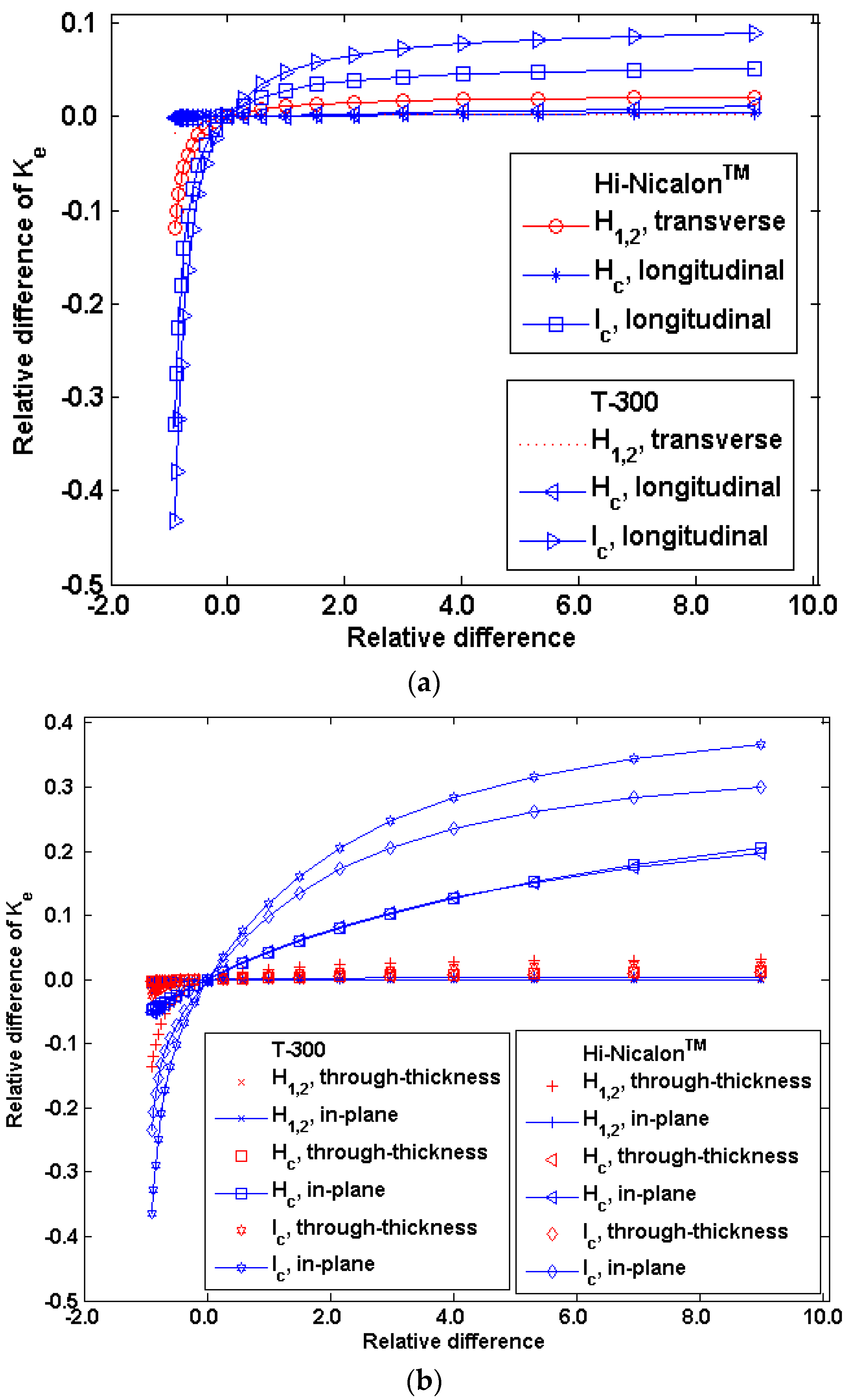

However, above models are developed on the assumption that the heat flux through the single fiber is not affected by the others, thus these developed formulae are valid only for dilute fiber concentrations. At higher volume-fractions of fiber, these formulae are approximate or even erroneous, for the local temperature fields around the fibers will interact. The differences between the calculated transverse thermal conductivity of two-phase model (as shown in

Figure 2b) and the prediction of self-consistent formula with the fiber-to-matrix conductivity ratio are shown in

Figure 4. The relative differences (RD) between both are illustrated by the following function:

where the subscripts MOD and FEM denote the

Ke values are calculated by the model and the simulation, respectively. It is found that the self-consistent formula can give a satisfactory prediction for all fiber structures when 0.01 <

< 100. When

< 0.01 or

> 100, the following fitting function can be used:

where

B has been defined by Equation (4). In

Figure 4, Equation (11) is shown to give a satisfactory agreement to our data. In most cases, the fiber-matrix ratio is at the range of 10

−2–10

2, thus the self-consistent formula (or Hasselman and Johnson’s model) is satisfactory for estimation.

To improve the interface between matrix and fiber, the fibers are coated by the pyrolytic carbon (PyC) interfacial layer before the deposition of the matrix. In self-consistent (Equation (6)) and H-J model (Equation (7)), a fiber is in the middle of a cylindrical matrix and the matrix is contained within an effectively homogeneous medium, which is very close to the situation of CVI processing if the thickness of the interfacial layer is not too large. Then the coated fiber with interface layer can be approximately treated as a homogeneous solid phase, whose volume fraction is (

Vf +

Vi), where

Vi is the volume fraction of the interfacial layer. In addition, the equivalent transverse thermal conductivity of the solid phase,

can be estimated according to H-J model:

where

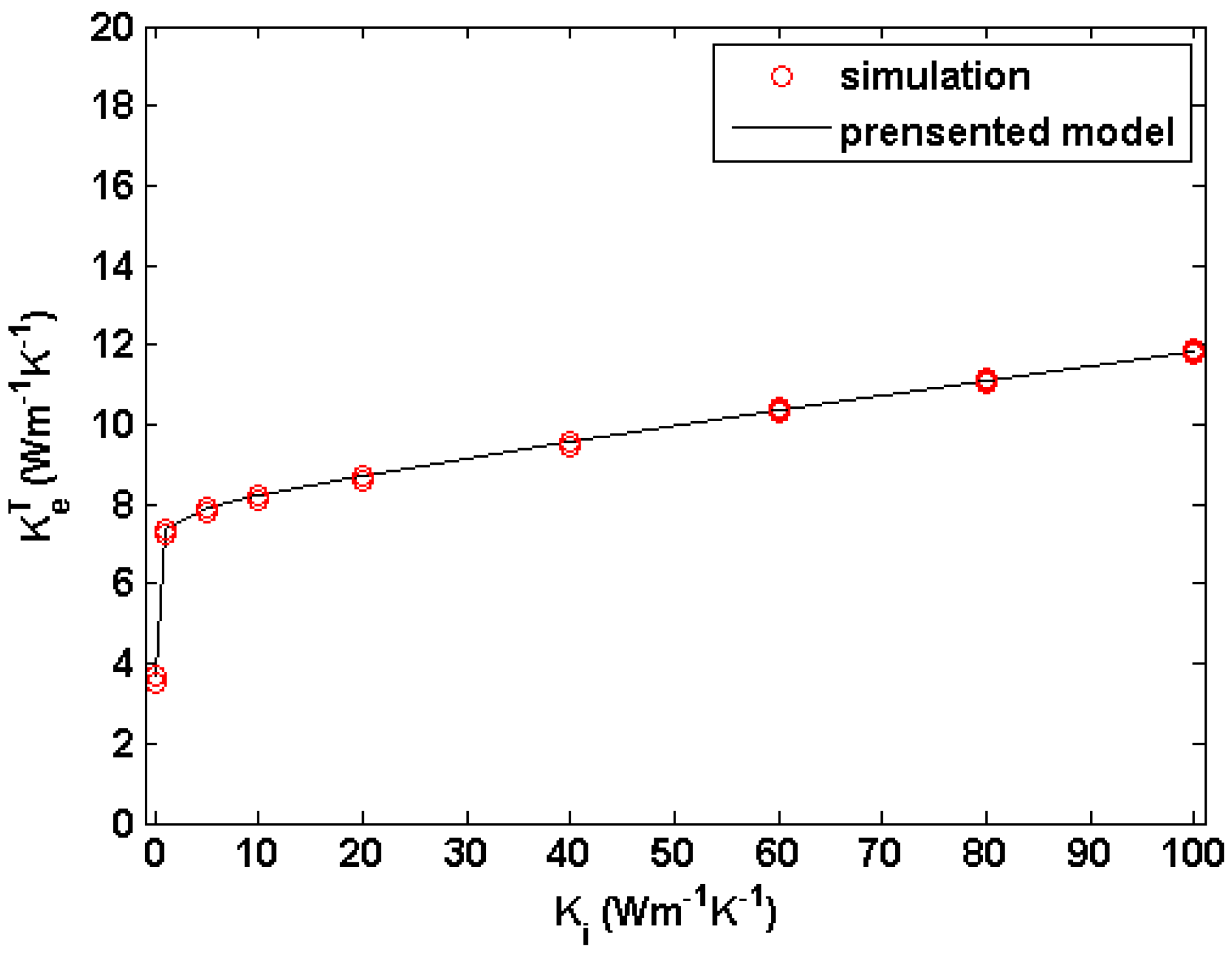

Ki is the thermal conductivity of the interfacial layer. Substituting Equation (12) into (6), the transverse thermal conductivity of the three-phase system can be estimated. To validate this model, by setting

= 3 W·m

−1·K

−1,

Km = 20 W·m

−1·K

−1,

Vf = 0.5 and

Vi = 0.05, the transverse thermal conductivity of the three-phase system (as shown in

Figure 2c) with

Ki values are calculated and shown in

Figure 5. It is clearly shown that the presented model gives a good fit to our simulation results.

Considering that the fiber, matrix and interfacial layer have the same thermal conductivity values,

Ks, above a certain pore concentration, the transverse thermal conductivities of the systems are the same order of magnitude as the thermal conductivity of the pore, which indicates that the pore phase is the dominant pathway for heat transfer. As the solid volume fraction is increased and larger than the ‘critical solid concentration’,

, the matrix deposited on the surfaces of the different fibers contact with each other and form a continuous path for heat transfer. Noted a parameter called the critical pore concentration has been frequently used to estimate the gas transport properties of the densified microstructure for CVI process, then the value of

can be determined by subtracting the critical pore concentration for 1-D partially overlapping fiber structure from one, the following expression can be given from our simulation results:

A phase interchange theorem is developed by Keller [

31] for two-dimensional statistically homogeneous, isotropic structures, which simply states that, the

value of this structure by interchanging the thermal conductivity values of fiber and matrix is equal to the reciprocal of the

value of the original structure. When

Vs is less than

, than Tomadakis and Sotirchos [

32] applied Keller’s theorem and related the transverse thermal transport of 1-D fiber structure when the fiber are high-conductive and the gas transport of 1-D overlapping fiber structure when the fiber are non-conductive:

where

is the reduce transverse thermal conductivity of the systems when the solid thermal conductivity is highly larger then the one of pore,

is the Fick diffusion tortuosity of the systems [

22].

Due to the local non-uniformity of the fiber structure, the coated fibers will overlap each other and form the local conductive chains. If the local conductive chains can be approximated as the fibers with elliptic cross-section, then the effective thermal conductivity of this material system can be estimated by Tsai-Halpin equations [

33,

34]:

for elliptic fibers with aspect ratios

e,

. Then the reduced transverse thermal conductivity of the systems can be obtained by Tsai-Halpin equations when the solid is high-conductive:

Combining Equations (14) and (16), we can obtain

Finally, the transverse thermal conductivity of the systems can be estimated by Equations (15) and (17) when Vs is less than .

When

Vs is larger than

, the pore can be seen as the isolative phase inside the solid media. Because the thermal conductivity of the pores is always less than the one of the solid by two orders, the pores can be practically seen as non-conductive. Fitting from the simulation data, 3 expression is made to put forth a porosity correction to thermal conductivity:

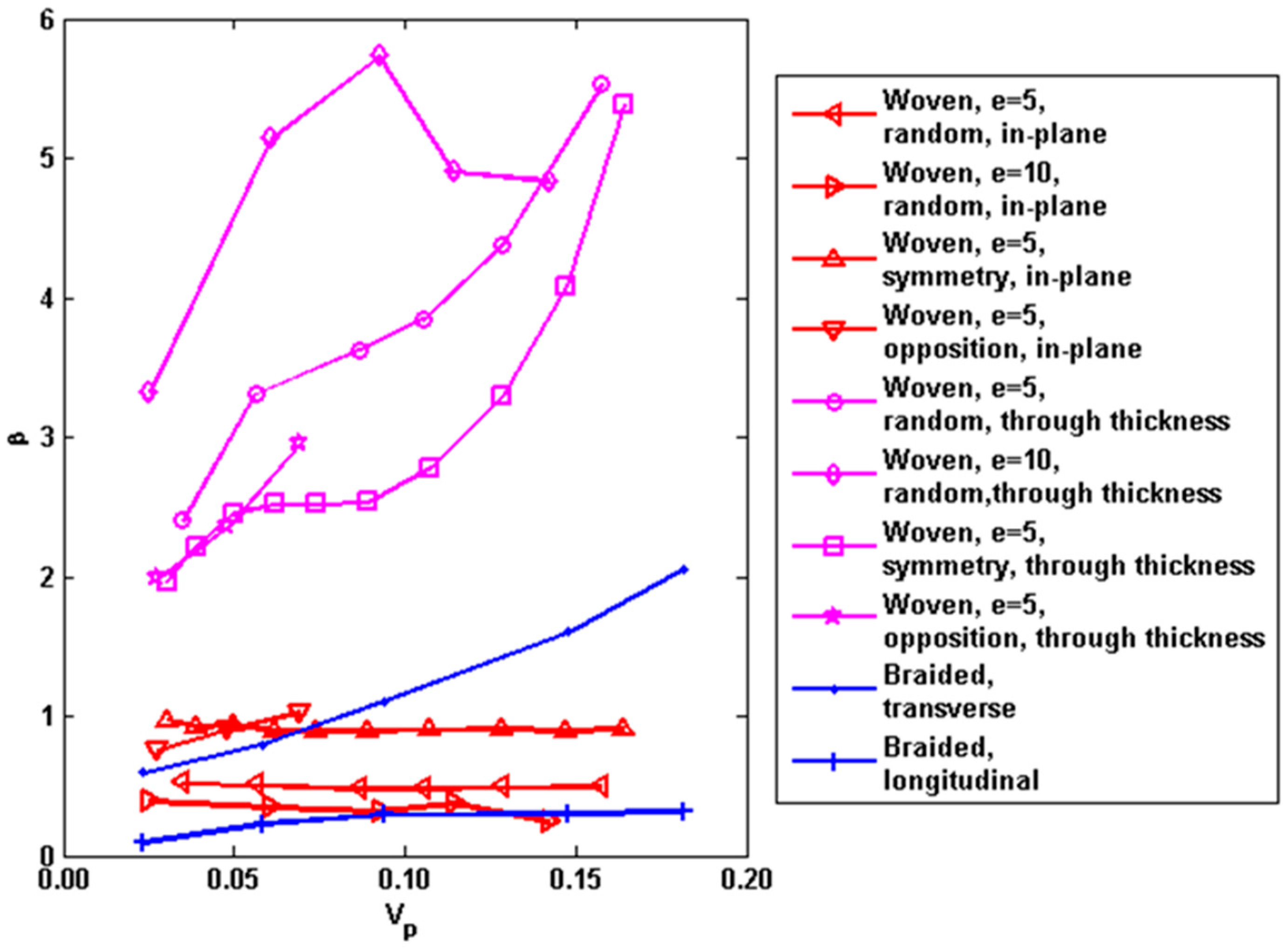

where

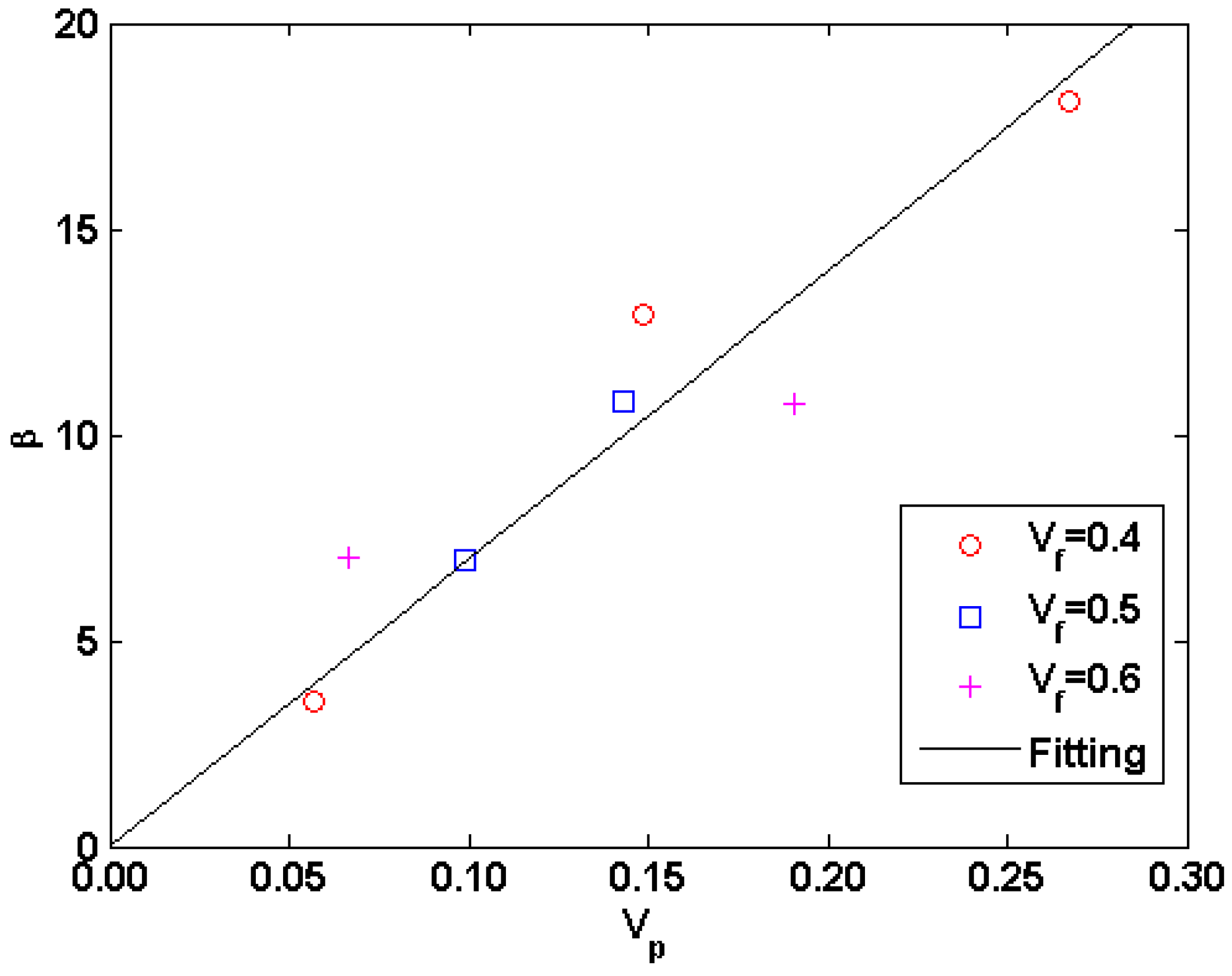

β is a pore shape factor. The obtained

β values are plotted in

Figure 6. It is found that the fluctuation of

β values is approximately increased with porosity throughout the entire porosity range. The values of

β are estimated as

β = 70

Vp with

R2 ≈ 0.88. Such high level of dispersion demonstrates that the thermal conductivity of the two-phase system could considerably be affected by the randomness of the geometry of the pores.

According to the previous discussions, the complete analytical model for four-phase system (as depicted in

Figure 2f) is developed as follow. The fiber coated with two layers of materials can be seen as the equivalent homogeneous solid, whose thermal conductivity is estimated by using Hasselman and Johnson’s model twice, first to replace the thermal conductivity of fiber coated with interface layer with the homogenous value, and second to replace the thermal conductivity of fiber coated with two layers of materials with the homogenous value, then the four-phase systems reduced to the two-phase systems. The complete analytical expressions are listed in

Table 1.

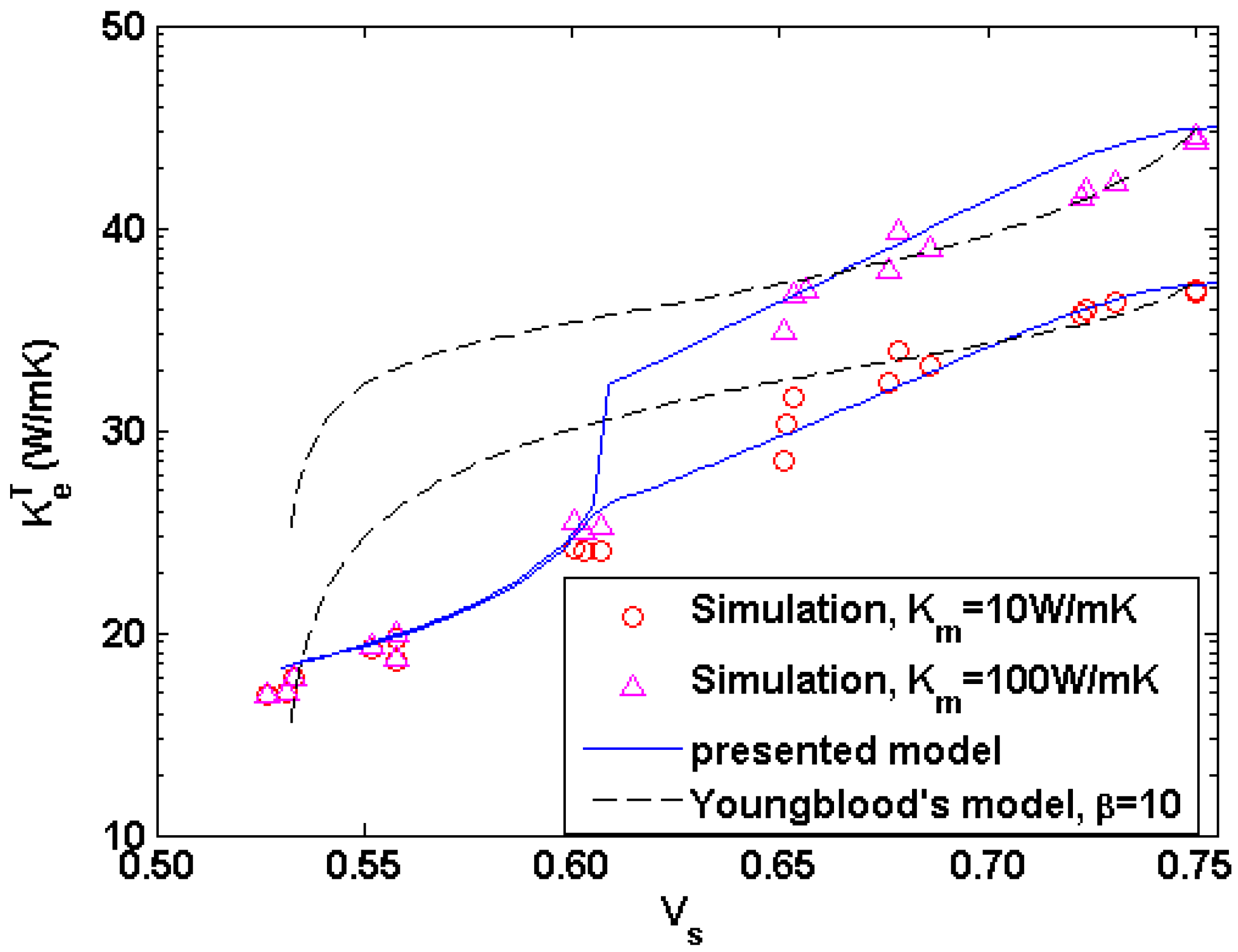

To validate the presented model, by assuming the perfect interface conductance and setting

= 1 W·m

−1·K

−1,

Ki = 40 W·m

−1·K

−1,

Km = 10 and 100 W·m

−1·K

−1,

Kp = 0.01 W m

−1·K

−1,

Vf = 0.5 and

Vi = 0.05, the transverse thermal conductivity of the densified microstructure with the solid volume fraction during the CVI process are calculated and compared with the presented and Youngblood’s expressions [

35] in

Figure 7. In Youngblood’s model, the thermal conductivity of matrix containing pores can be estimated as the one of homogeneous media,

by the Maxwell-Eucken expression:

Then the effective thermal conductivity of a composite with a well-bonded fiber coating can be estimated by “3-cylinder” Markworth’s model [

36]:

where

C and

D are given by

where

rint is the thickness of the interface layer. It is clearly shown that the present model is consistent with the simulation results throughout the entire range of solid fraction, while Youngblood’s model agrees well with the simulation results by setting

value as 10 when porosity is less than 20%.