Time-Dependent Damage Investigation of Rock Mass in an In Situ Experimental Tunnel

Abstract

:1. Introduction

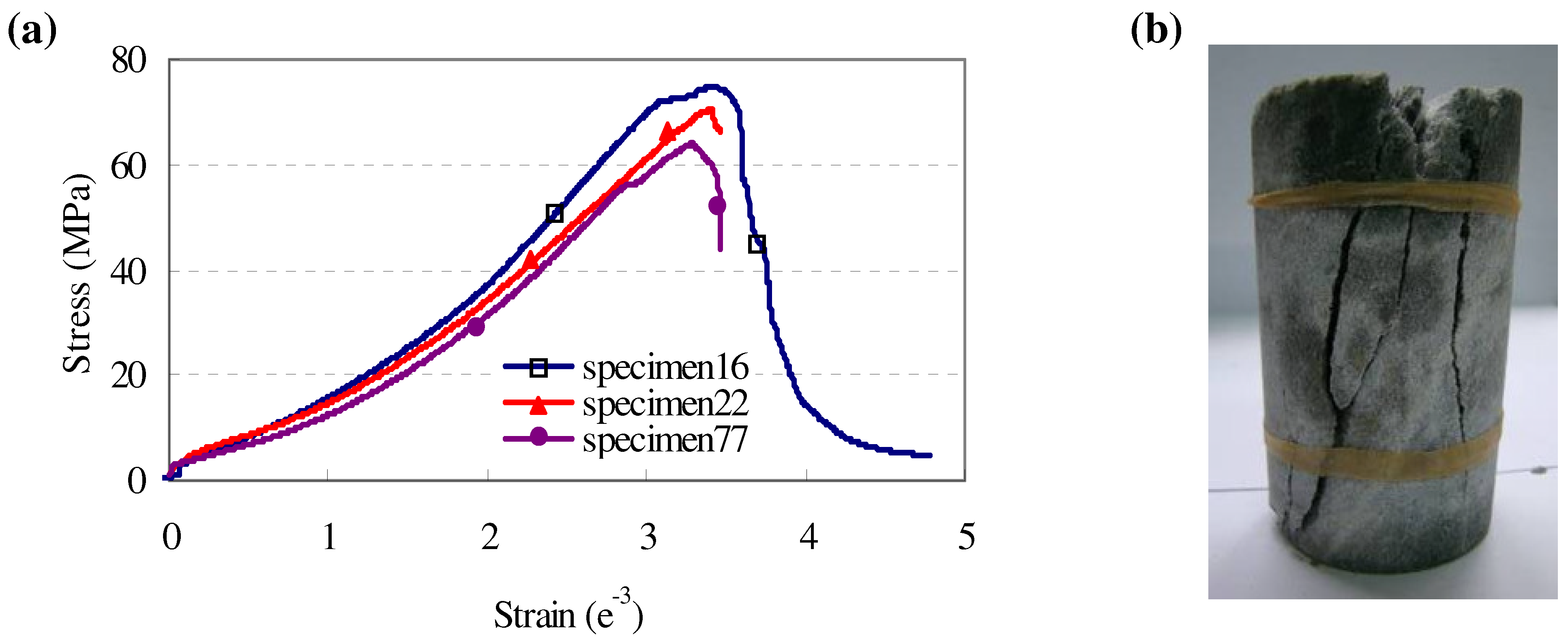

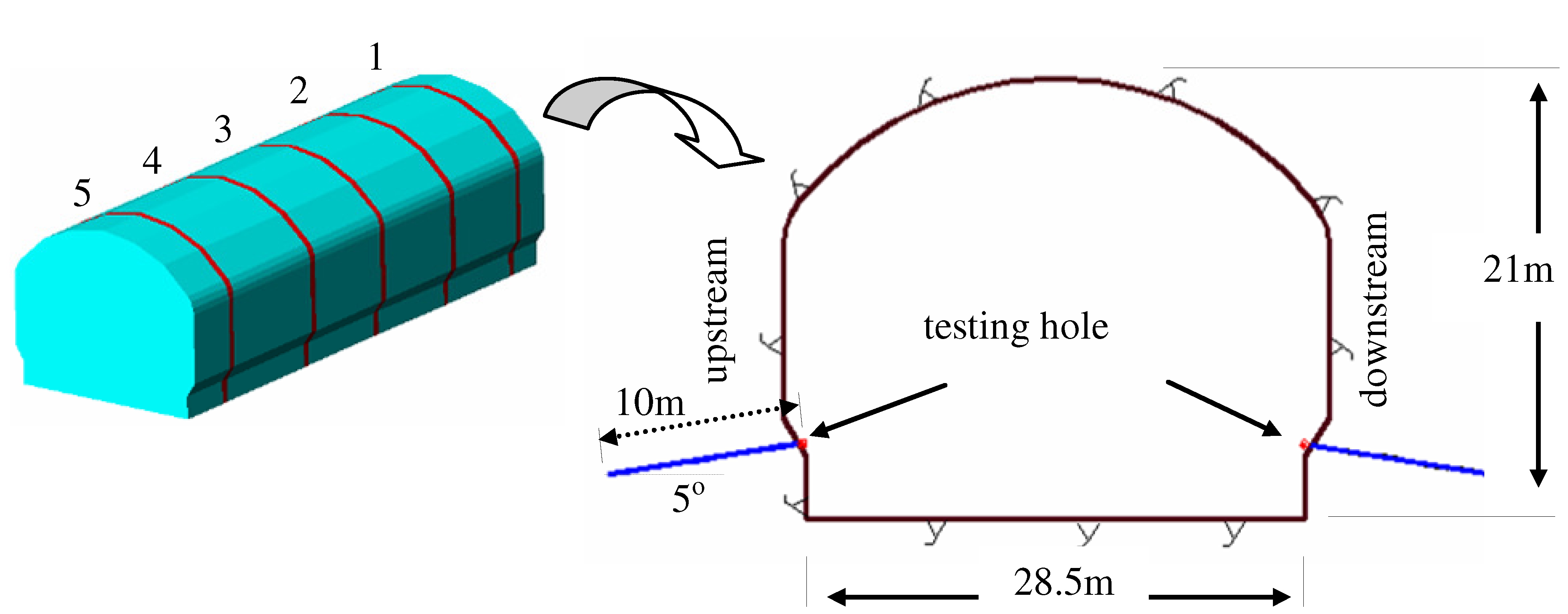

2. Information Regarding the Experimental Tunnel and Testing Method

2.1. Experimental Position

2.2. Testing Instruments and Methods

3. Analysis of Time-Dependent Damage

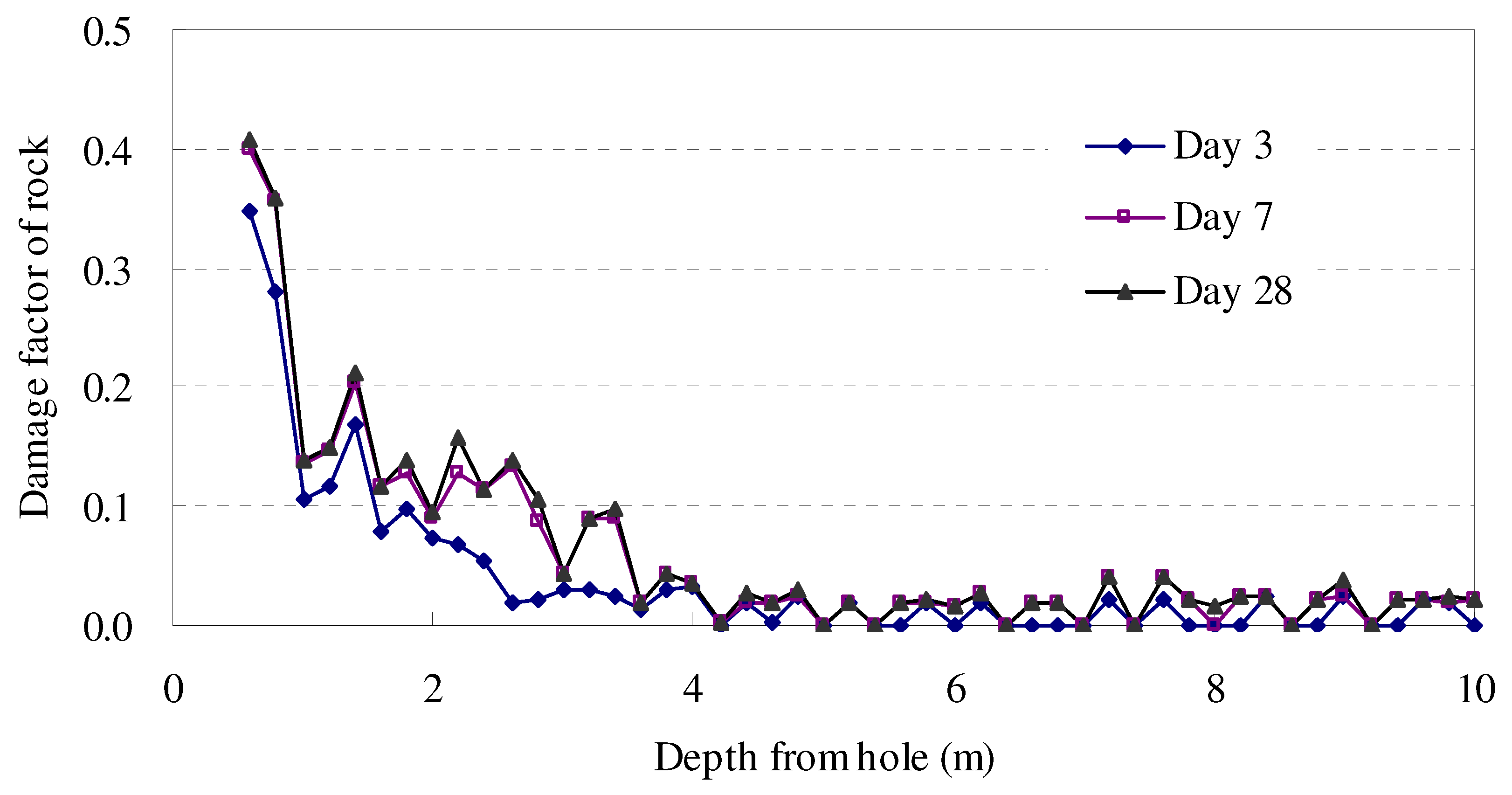

3.1. Basic Characters of Measured Ultrasonic Wave

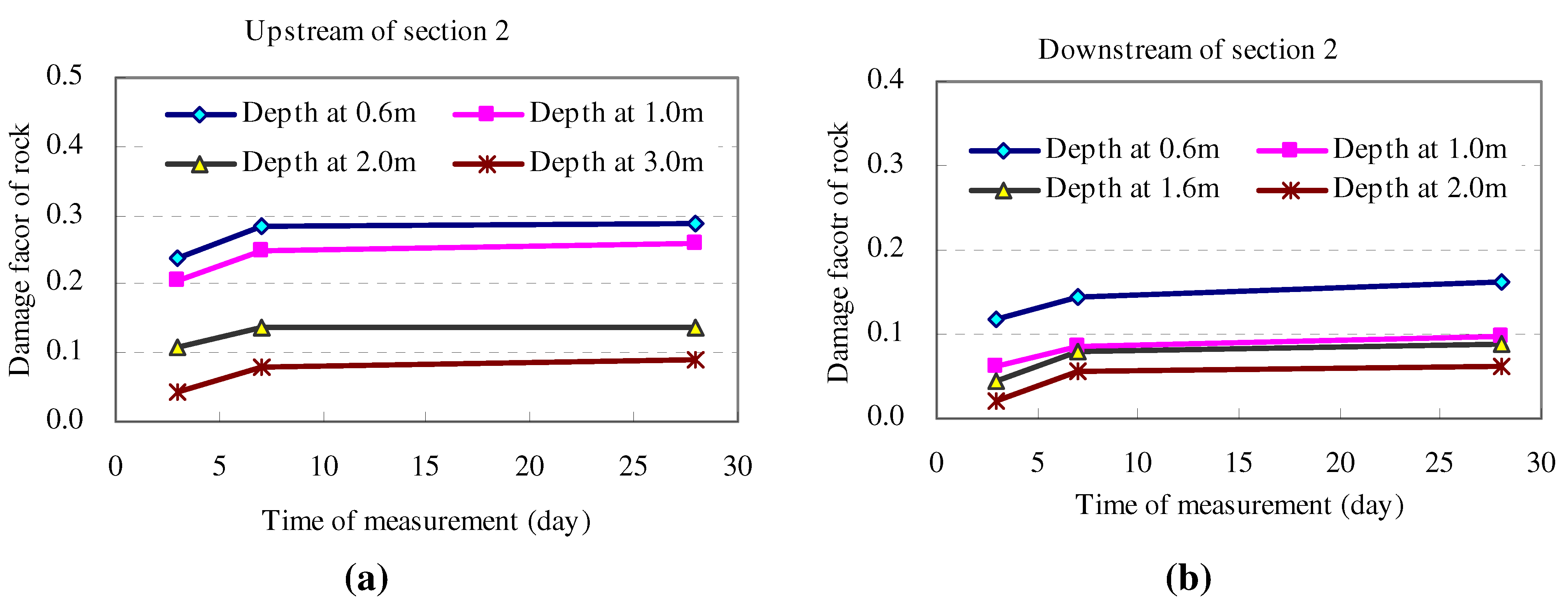

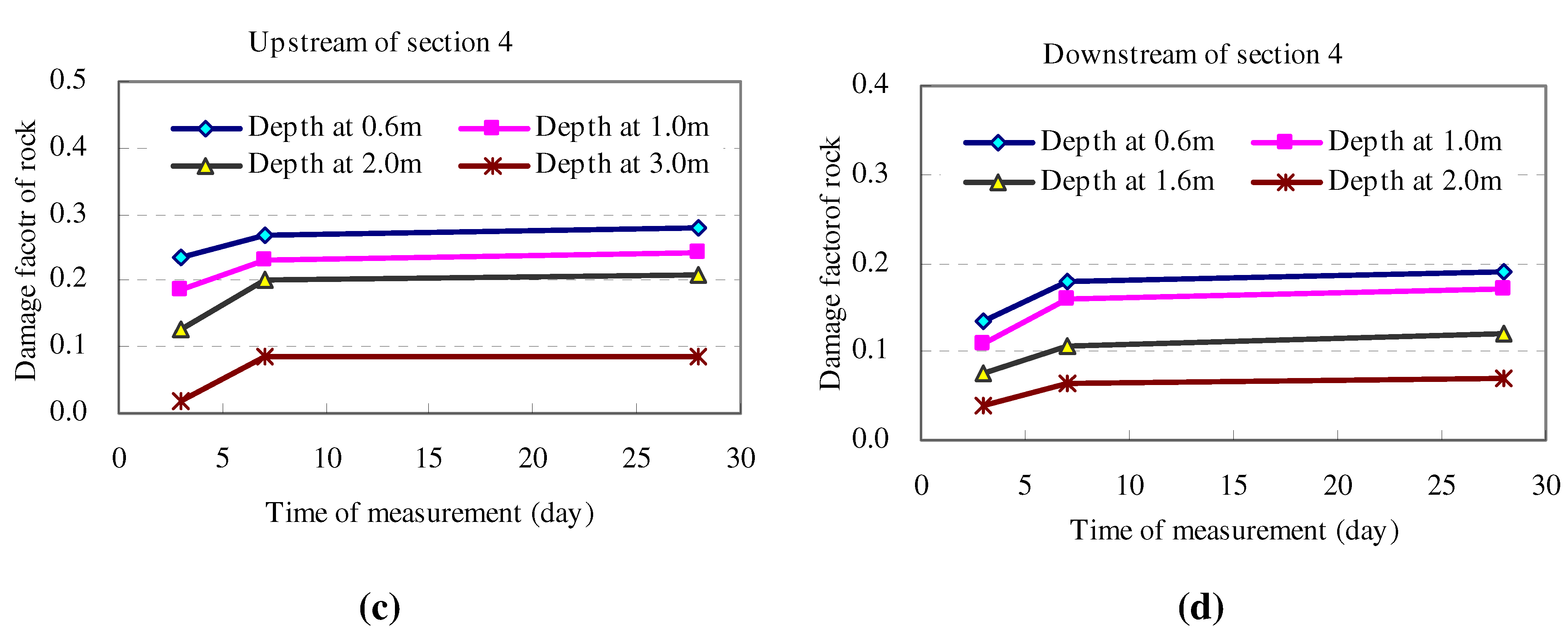

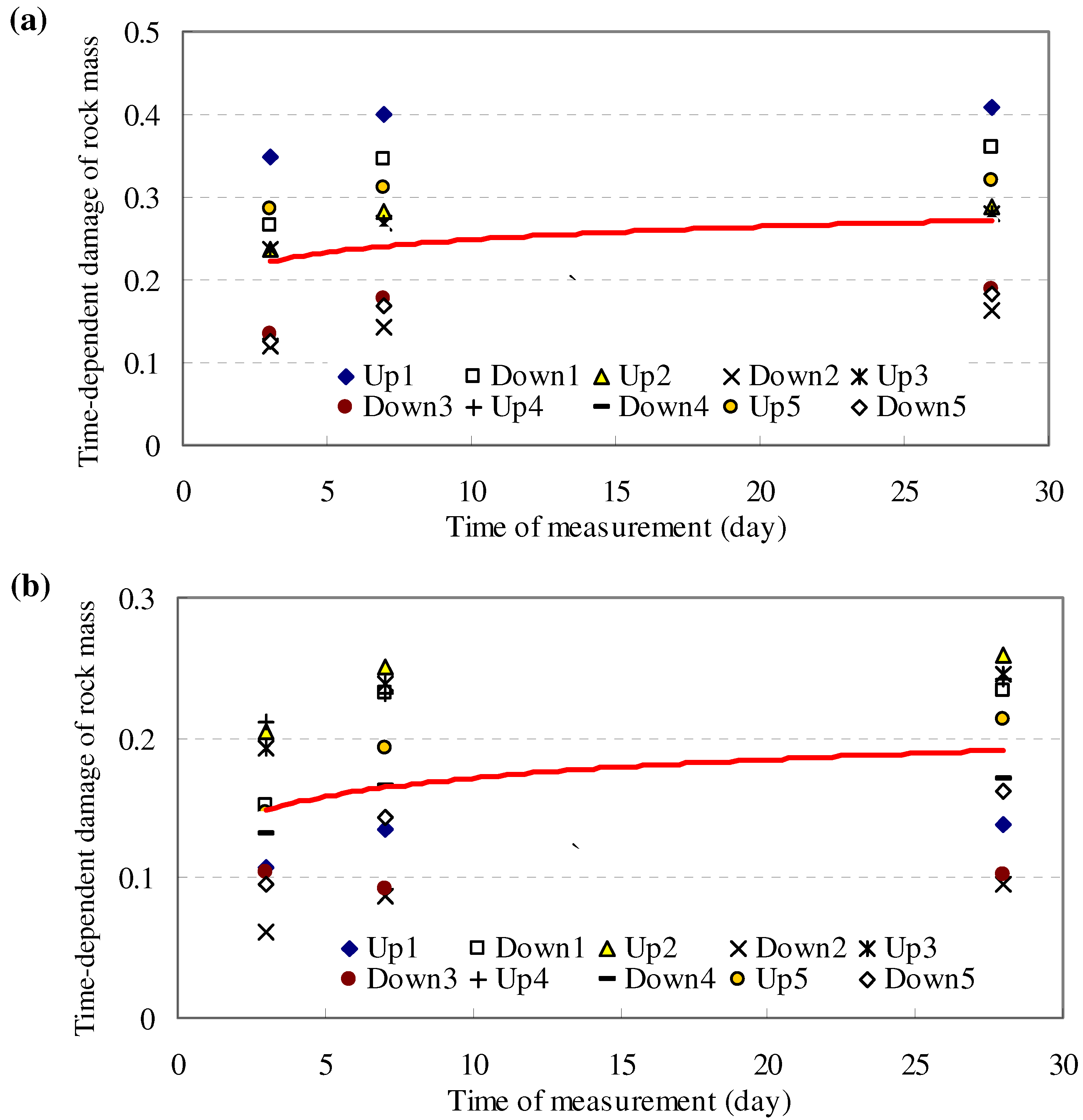

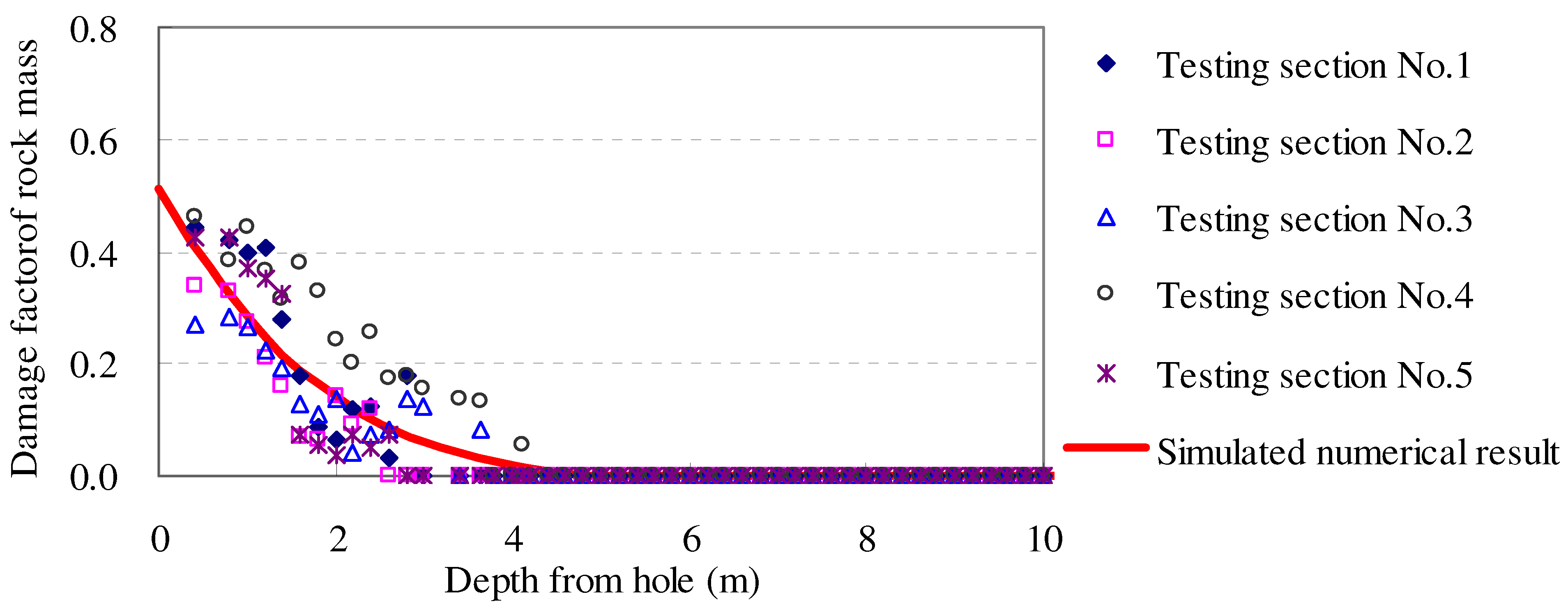

3.2. Time-Dependent Damage Evolution of Rock Mass

| Position (m) | Format | Residual |

|---|---|---|

| 0.6 | Logarithm | 0.2155 |

| Power | 0.4467 | |

| Exponential | 0.3148 | |

| 2.0 | Logarithm | 0.0595 |

| Power | 0.0695 | |

| Exponential | 0.0644 |

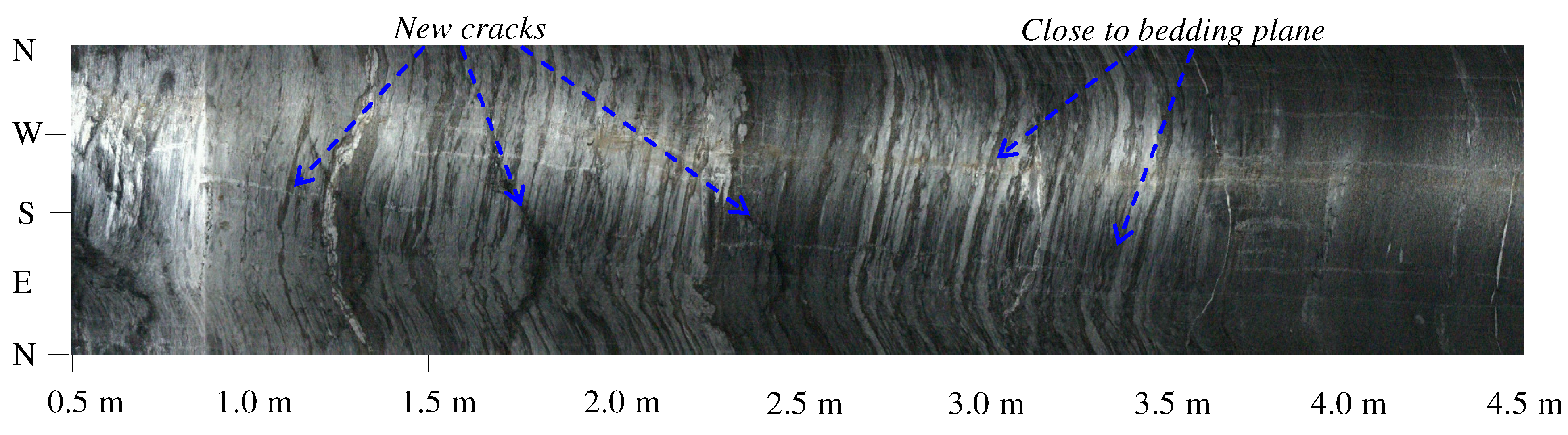

3.3. Time-Dependent Damage Mechanism

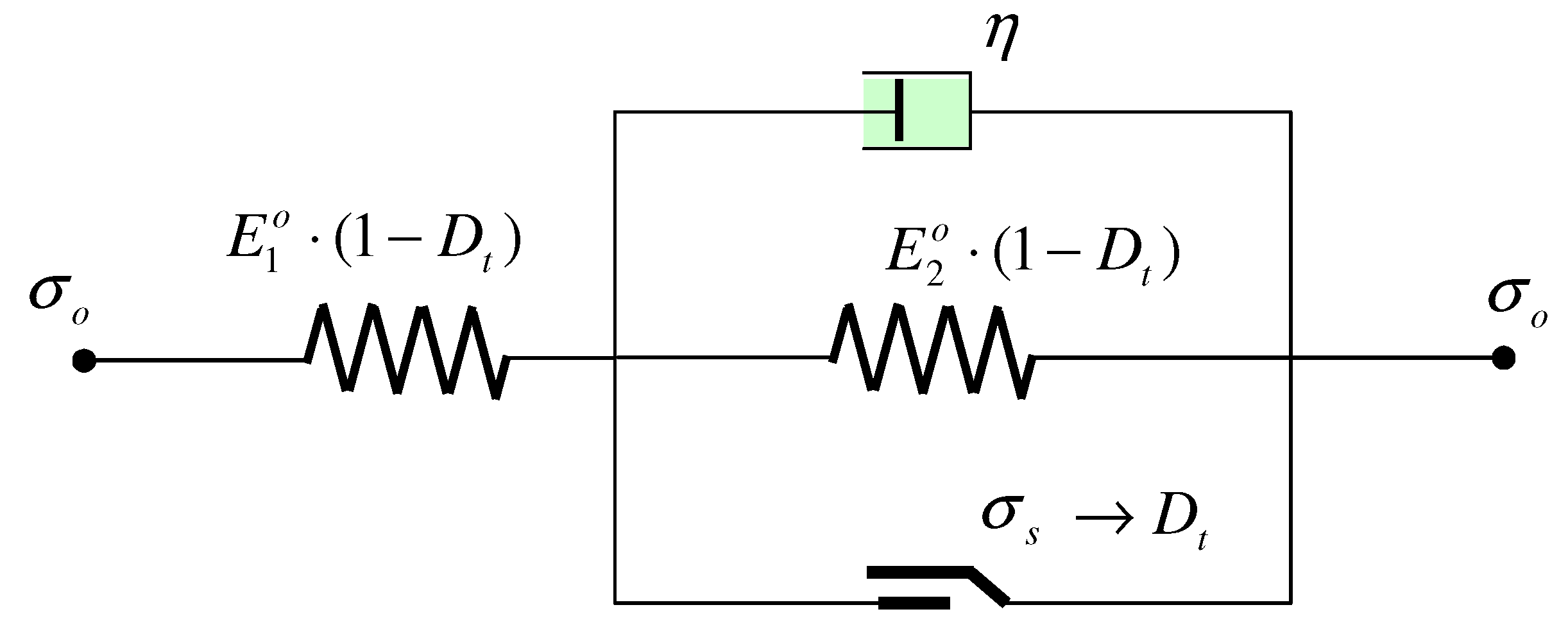

4. Numerical Descriptions

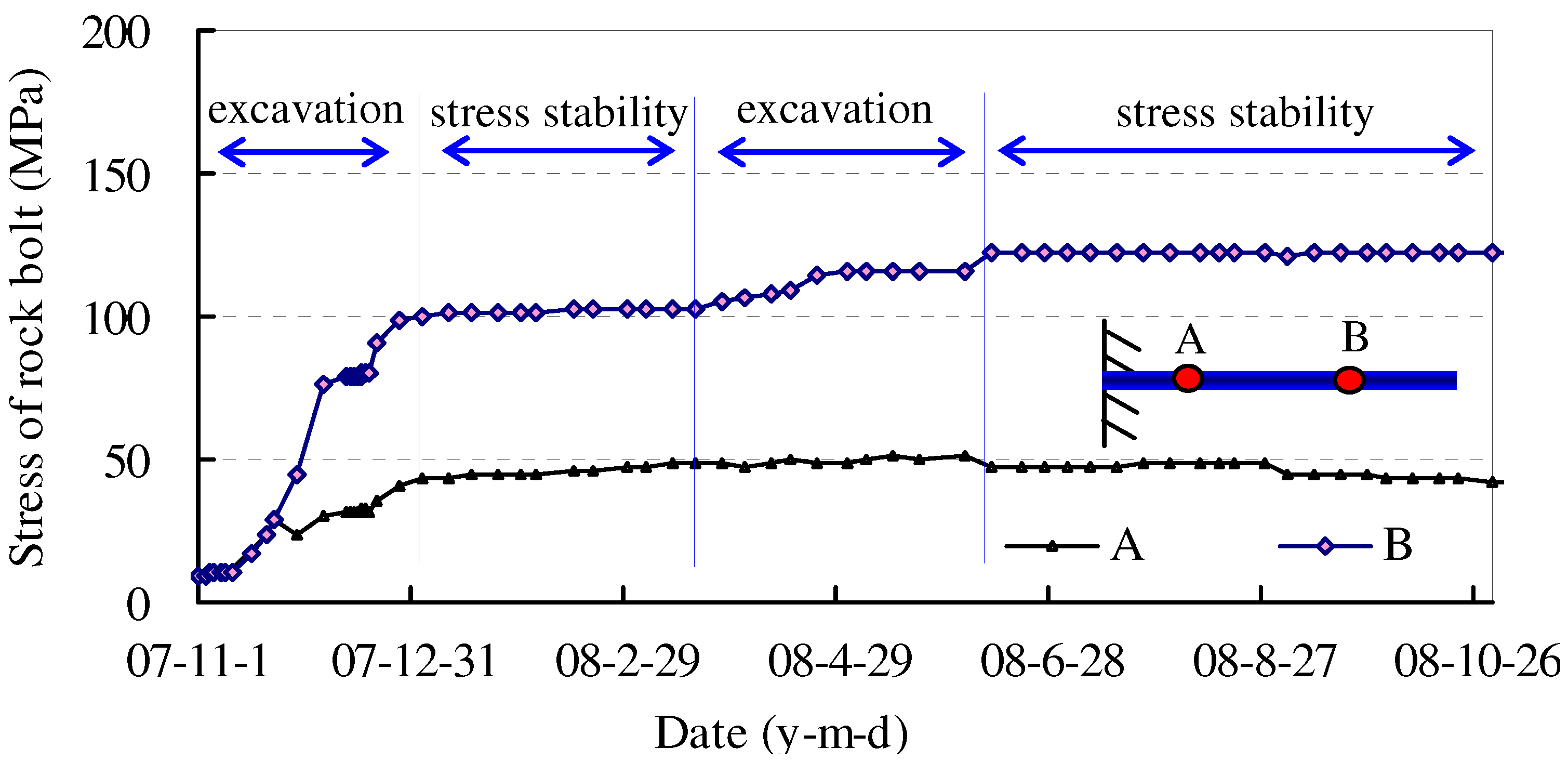

5. Damage Rehabilitation of Rock Mass

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

References

- Grady, D.E.; Kipp, M.E. Dynamic Rock Fragmentation; Academic Press: London, UK, 1987; pp. 429–475. [Google Scholar]

- Blair, S.C.; Cook, N. Analysis of compressive fracture in rock using statistical techniques: Part II. Effect of microscale heterogeneity on macroscopic deformation. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 1998, 35, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.H.; Ma, S.P.; Xia, M.F.; Ke, F.J.; Bai, Y.L. Damage evaluation and damage localization of rock. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2004, 42, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Qian, Q.; Zhang, Y. The constitutive relation of crack-weakened rock masses under axial-dimensional unloading. Acta Mech. Solida Sinica 2008, 21, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, J.B.; Chandler, N.A. Excavation-induced damage studies at the underground research laboratory. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 2004, 41, 1413–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maejima, T.; Morioka, H.; Mori, T.; Aoki, K. Evaluation of loosened zones on excavation of a large underground rock cavern and application of observational construction techniques. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2003, 18, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.Y.; Nie, W.P.; Zhou, X.Q.; Shi, C.; Wang, W.; Feng, S.R. Long-term stability analysis of large-scale underground plant of Xiangjiaba hydro-power station. J. Cent. South Univ. Technol. 2011, 18, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.D.; Read, R.S.; Martino, J.B. Observations of brittle failure around a circular test tunnel. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 1997, 34, 1065–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairhurst, C.; Damjanac, B. The excavation damaged zone—An international perspective. In Proceedings of the Excavation Disturbed Zone Workshop-Designing the Excavation Disturbed Zone for a Nuclear Waste Repository in Hard Rock; Canadian Nuclear Society: Manitoba, Canada, 1996; pp. 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Feng, X.T.; Xiang, T.B.; Su, G.S. Rockburst characteristics and numerical simulation based on a new energy index: A case study of a tunnel at 2500 m depth. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2010, 69, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Kaiser, P.K.; Martin, C.D. Quantification of rock mass damage in underground excavations from microseismic event monitoring. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 2001, 38, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.A.; Lin, P.; Wong, R.H.C.; Chau, K.T. Analysis of crack coalescence in rock-like materials containing three flaws—Part II: Numerical approach. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 2001, 38, 925–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, R.; Lin, P.; Tang, C.A.; Chau, K.T. Creeping damage around an opening in rock-like material containing non-persistent joints. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2002, 69, 2015–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabre, G.; Pellet, F. Creep and time-dependent damage in argillaceous rocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 2006, 43, 950–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.F.; Chau, K.T.; Feng, X.T. Modeling of anisotropic damage and creep deformation in brittle rocks. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 2006, 43, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Guo, H.; Gao, Y. Creep damage characteristics of soft rock under disturbance loads. J. China Univ. Geosci. 2008, 19, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rist, M.A.; Plumbridge, W.J.; Cooper, S. Creep-constitutive behavior of Sn-3.8Ag-0.7Cu solder using an internal stress approach. J. Electron. Mater. 2006, 35, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amitrano, D.; Helmstetter, A. Brittle creep, damage, and time to failure in rocks. J. Geophys. Res. B Solid Earth 2006, 111, B11201:1–B11201:17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plumbridge, W.J. New avenues for failure analysis. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2009, 16, 1347–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.S.; Bodner, S.R.; Fossum, A.F.; Munson, D.E. A damage mechanics treatment of creep failure in rock salt. Int. J. Damage Mech. 1997, 6, 121–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Hou, C.; Yang, M.; He, Y. Law of rock strength weakening around roadway and its application. J. China Univ. Min. Technol. 1999, 28, 133–135. [Google Scholar]

- Naoi, M.; Ogasawara, H.; Takeuchi, J.; Yamamoto, A.; Shimoda, N.; Morishita, K.; Ishii, H.; Nakao, S.; van Aswegen, G.; Mendecki, A.J.; Lenegan, P.; Ebrahim-Trollope, R.; Loi, Y. Small slow-strain steps and their forerunners observed in gold mine in South Africa. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, L12304:1–L12304:6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogianni, V.; Papantonopoulos, C.; Stiros, S. Delayed failure at the Messochora tunnel, Greece. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2008, 23, 232–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Kikuchi, T.; Sugihara, K. In situ experiments on an excavation disturbed zone induced by mechanical excavation in Neogene sedimentary rock at Tono mine, central Japan. Dev. Geotech. Eng. 2000, 56, 97–108. [Google Scholar]

- Meglis, I.L.; Chow, T.; Martin, C.D.; Young, R.P. Assessing in situ microcrack damage using ultrasonic velocity tomography. Int. J. Rock Mech. Mining Sci. 2005, 42, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmgren, L.; Saiang, D.; Toyra, J.; Bodare, A. The excavation disturbed zone (EDZ) at Kiirunavaara mine, Sweden—By seismic measurements. J. Appl. Geophys. 2007, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachanov, L.M. Time of the rupture process under creep conditions. Izv. Akad. Nauk. SSSR, Otd. Tech. Nauk. 1958, 8, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Broberg, H. A new criterion for brittle creep rupture. J. Appl. Mech. 1974, 41, 809–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalewski, Z.L.; Hayhurst, D.R.; Dyson, B.F. Mechanisms-based creep constitutive equations for an aluminium alloy. J. Strain Anal. 1994, 29, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, O.; Popp, T.; Kern, H. Development of damage and permeability in deforming rock salt. Eng. Geol. 2001, 61, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.A.; Hyde, T.H.; Sun, W.; Andersson, P. Benchmarks for finite element analysis of creep continuum damage mechanics. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2002, 25, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, N.; Lien, R.; Lunde, J. Engineering classification of rock masses for the design of tunnel support. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 1974, 6, 189–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniawski, Z.T. Determining rock mass deformability: Experience from case histories. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1978, 15, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, D. The study on rock mass deforming parameters and relaxing thickness of rock high slope. Adv. Earth Sci. 2004, 19, 472–477. [Google Scholar]

- Vairavamurthy, M.A.; Manowitz, B.; Maletic, D.; Wolfe, H.; Baud, P.; Meredith, P.G. Damage accumulation during triaxial creep of darley dale sandstone from pore volumometry and acoustic emission. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1997, 34, 371–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randy, J.G.; Francis, A.C. The strain-controlled creep damage law and its application to the rupture analysis of thick-walled tubes. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 1988, 23, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, C. 3D creep constitutive equation of modified Nishihara model and its parameters identification. Chin. J. Rock Mech. Eng. 2012, 31, 347–355. [Google Scholar]

- Zienkiewicz, O.; Humpheson, C.; Lewis, R. Associated and non-associated visco-plasticity and plasticity in soil mechanics. Geotechnique 1975, 25, 671–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, Q.; Cui, J.; Chen, J. Time-Dependent Damage Investigation of Rock Mass in an In Situ Experimental Tunnel. Materials 2012, 5, 1389-1403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma5081389

Jiang Q, Cui J, Chen J. Time-Dependent Damage Investigation of Rock Mass in an In Situ Experimental Tunnel. Materials. 2012; 5(8):1389-1403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma5081389

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Quan, Jie Cui, and Jing Chen. 2012. "Time-Dependent Damage Investigation of Rock Mass in an In Situ Experimental Tunnel" Materials 5, no. 8: 1389-1403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma5081389

APA StyleJiang, Q., Cui, J., & Chen, J. (2012). Time-Dependent Damage Investigation of Rock Mass in an In Situ Experimental Tunnel. Materials, 5(8), 1389-1403. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma5081389