Prediction of the Time-Dependent Elastic Modulus of Fly-Ash Concrete Under Sustained Loads

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Framework

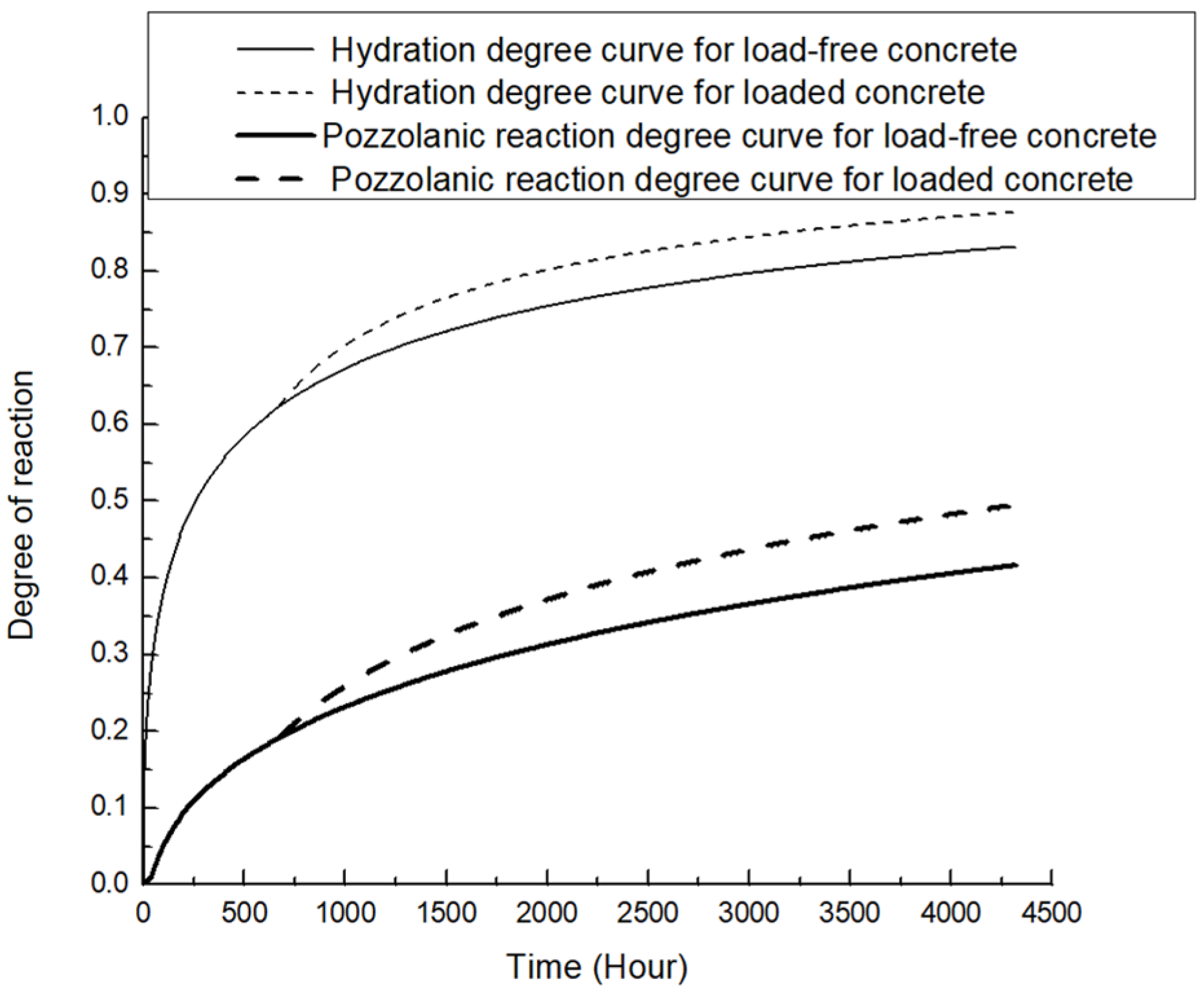

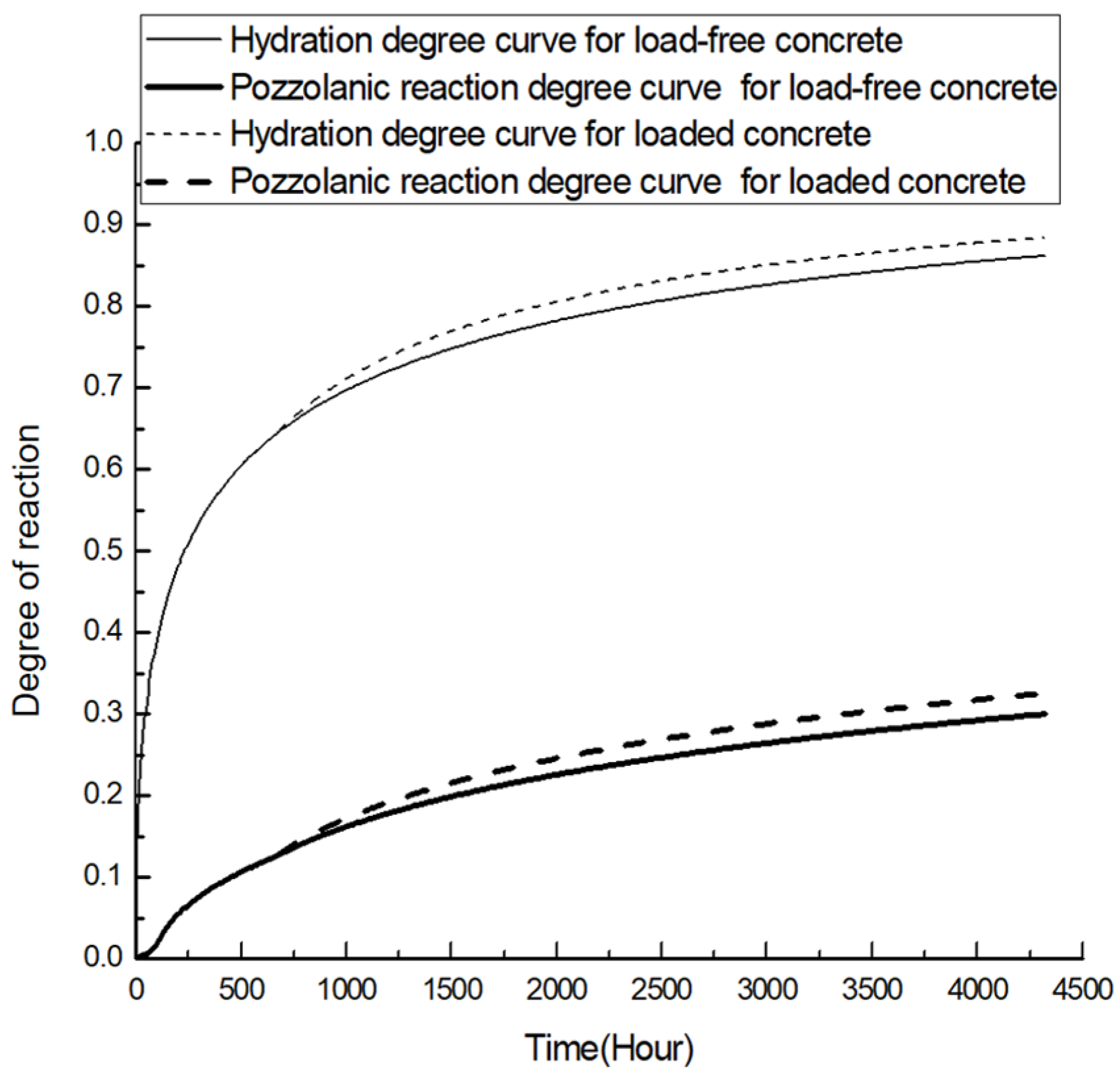

2.1.1. Discussion of the Mechanism

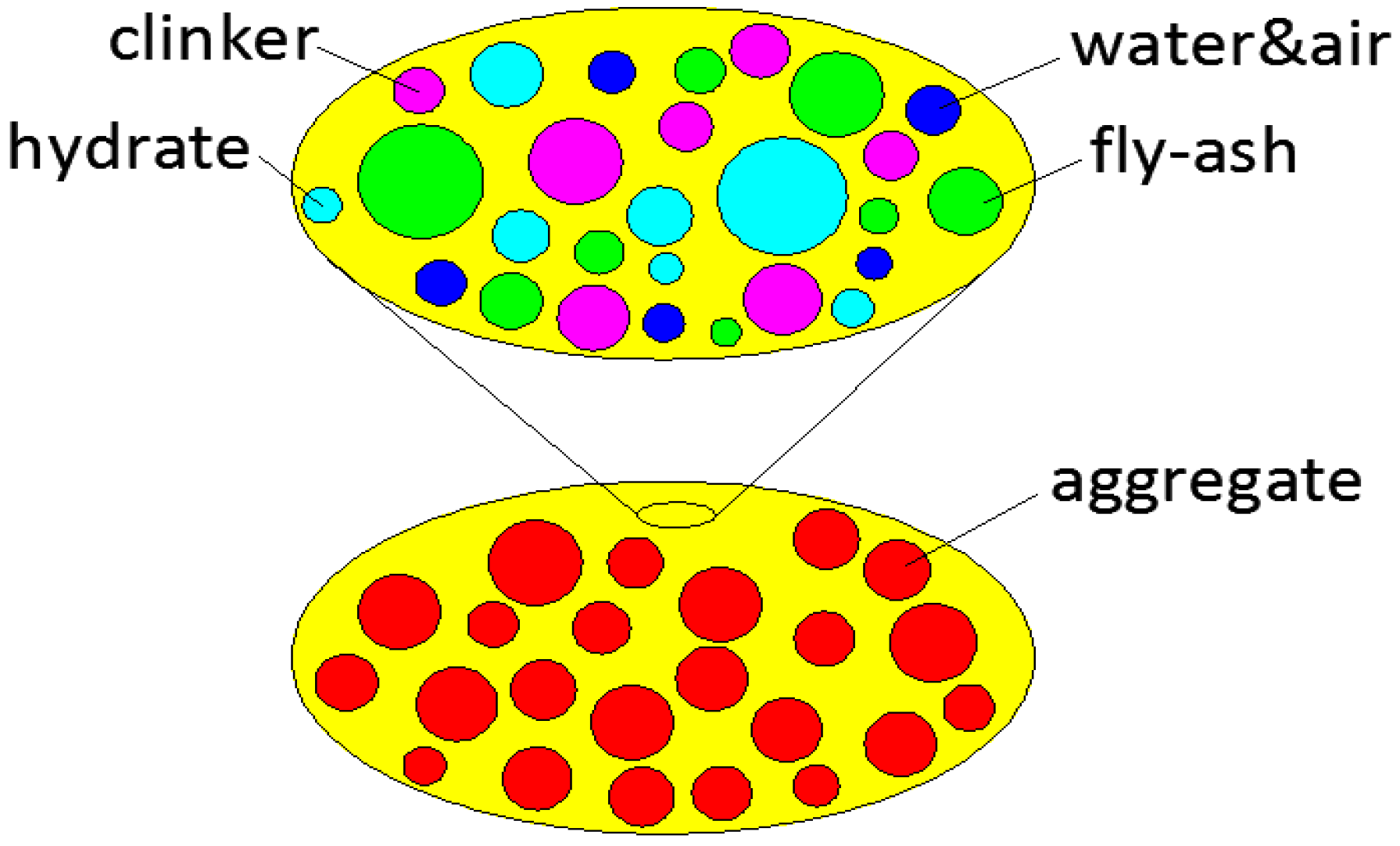

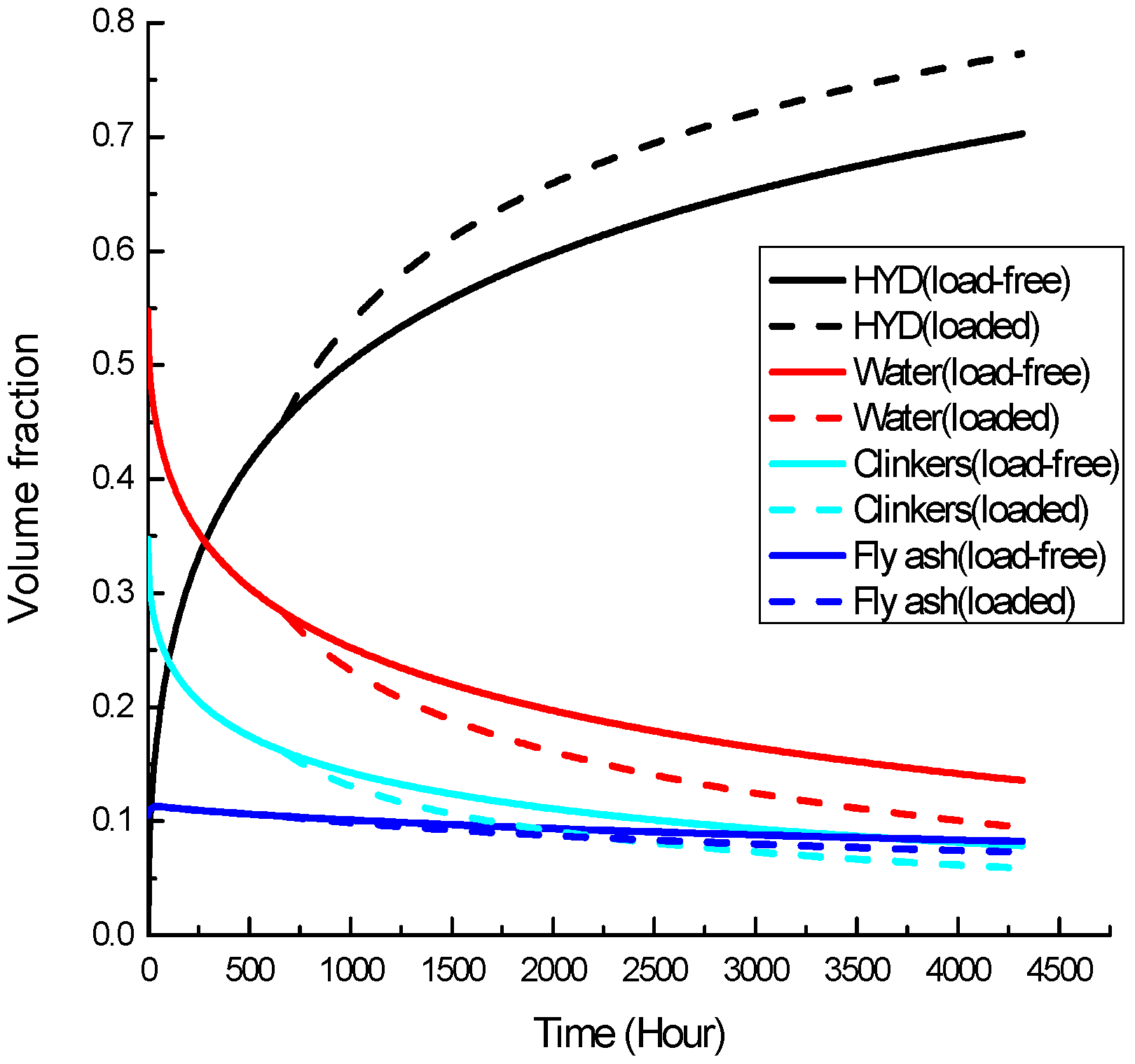

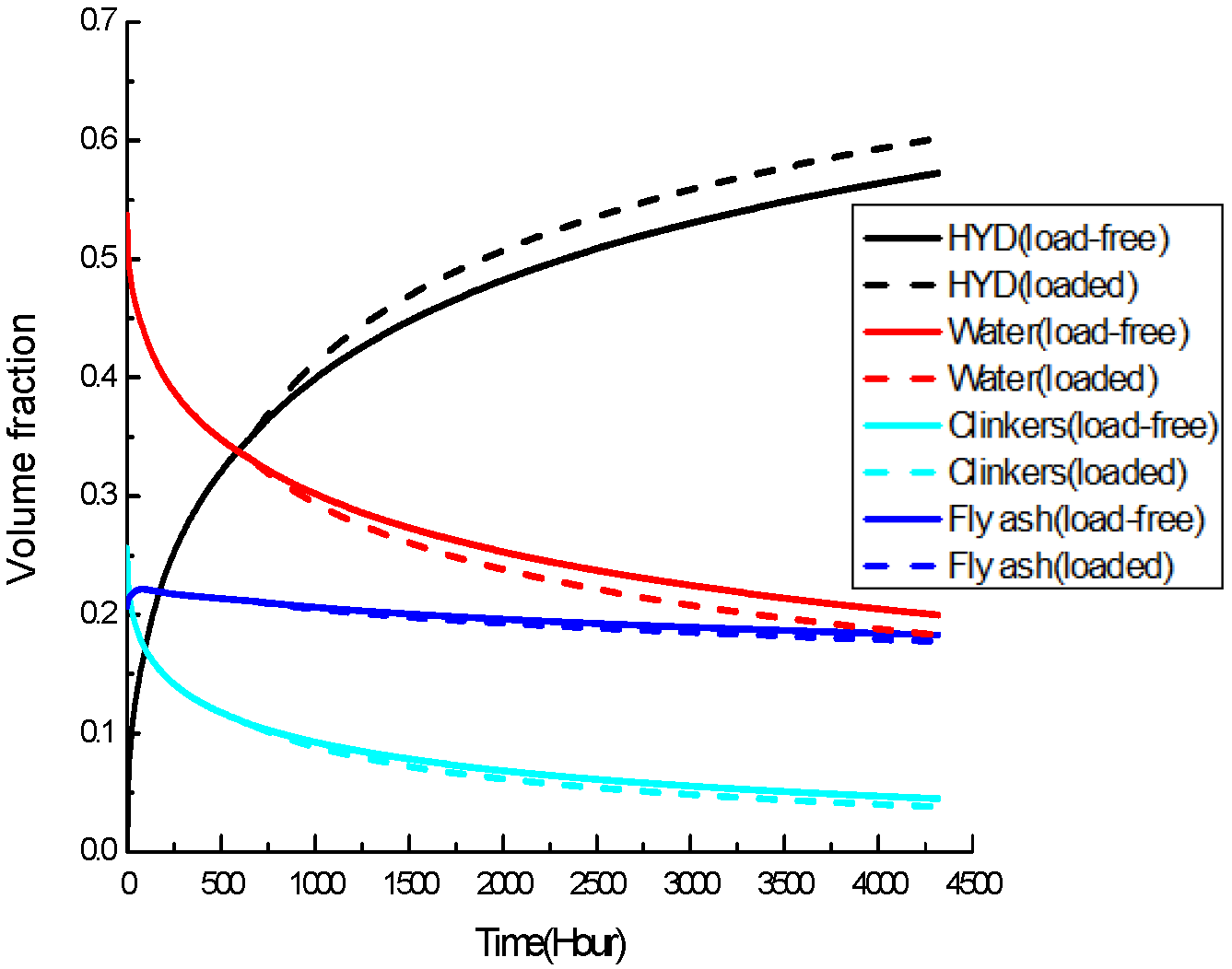

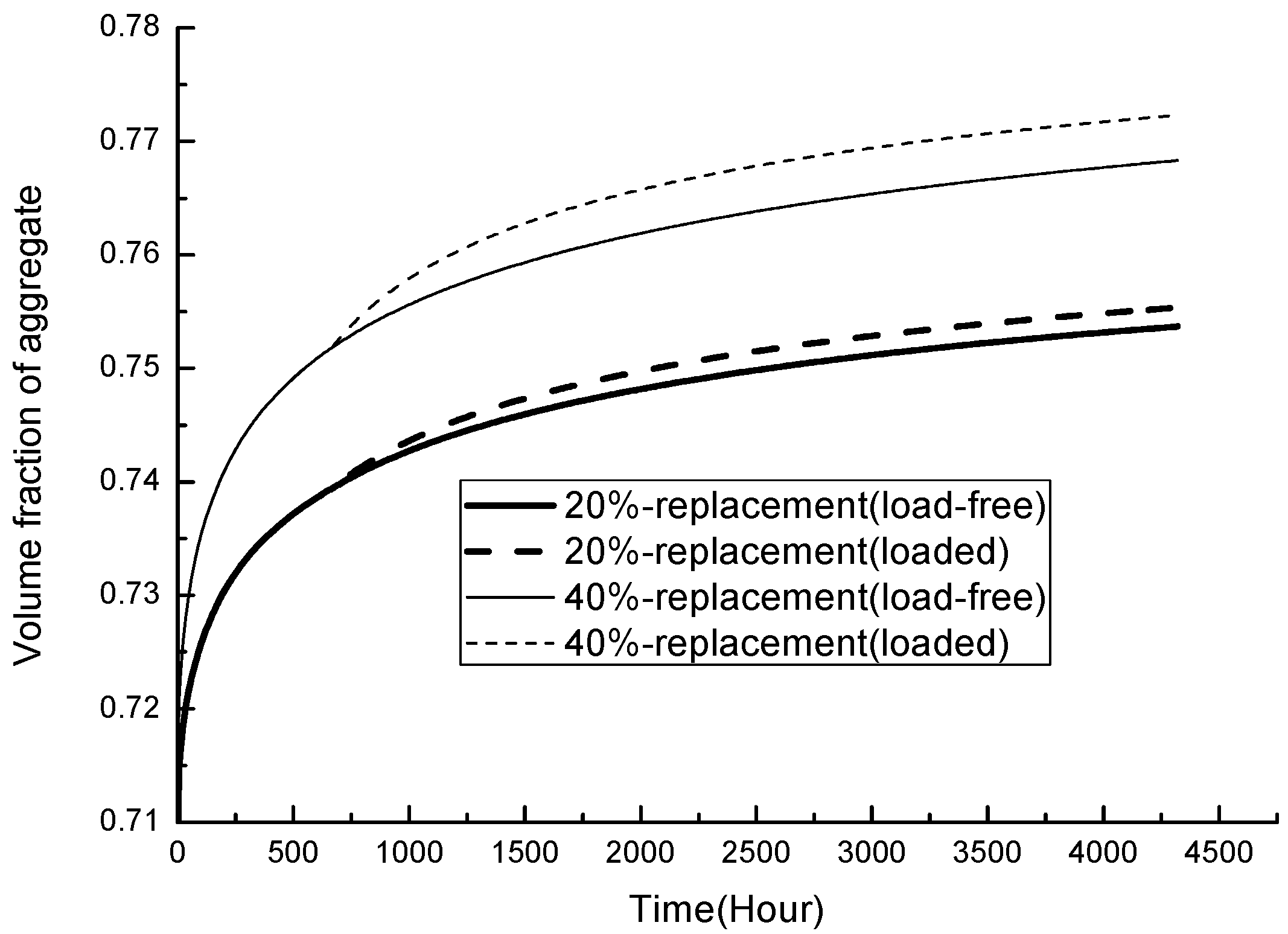

2.1.2. Micromechanical Representation of Fly-Ash Concrete

2.1.3. Time-Dependent Development of the Elastic Modulus of Fly-Ash Concrete

2.2. Materials

2.3. Experimental Program and Testing Procedures

2.3.1. Specimen Preparation and Curing Conditions

2.3.2. Compressive Strength Basis and Loading Levels

2.3.3. Elastic Modulus Measurement Protocol

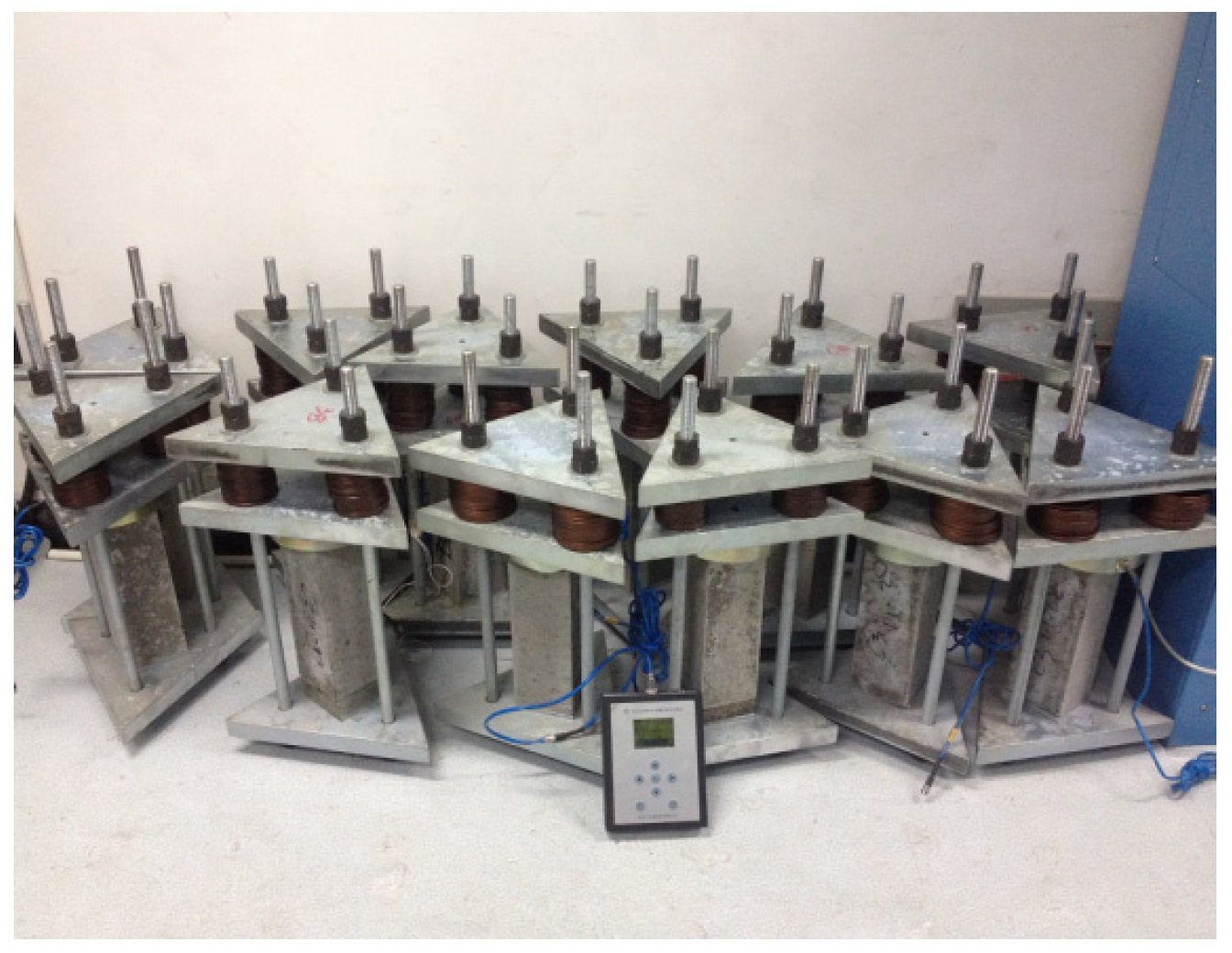

2.3.4. Sustained Load Application and Monitoring

2.3.5. Experimental Design

3. Results and Discussion

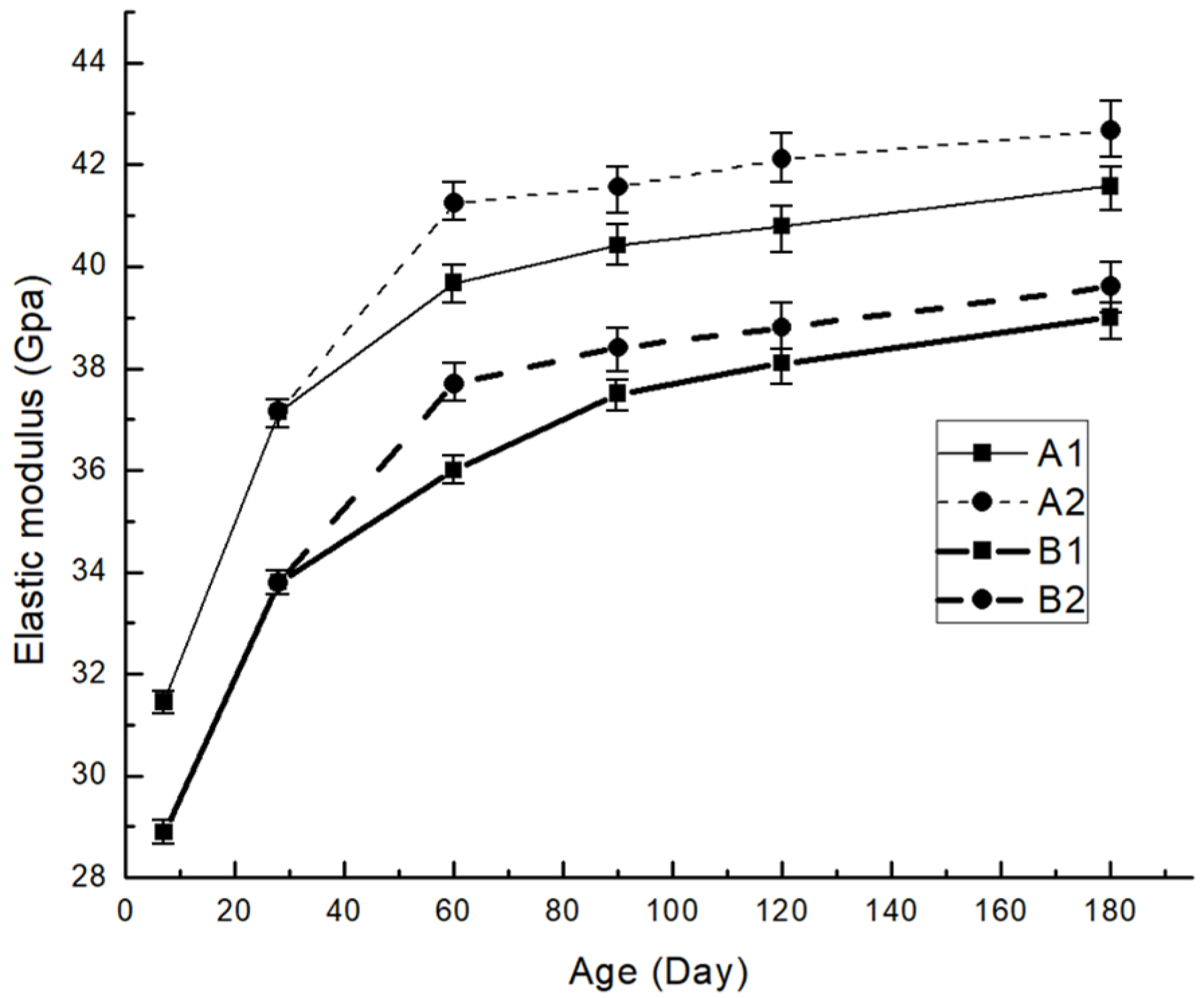

3.1. Experimental Results

3.2. Model Validation

3.2.1. Model Assumptions and Scope

3.2.2. Model Inputs and Calibration Strategy

- (I)

- Fixed Model Inputs

- (II)

- Calibration of Load Factors

- (III)

- Validation Approach

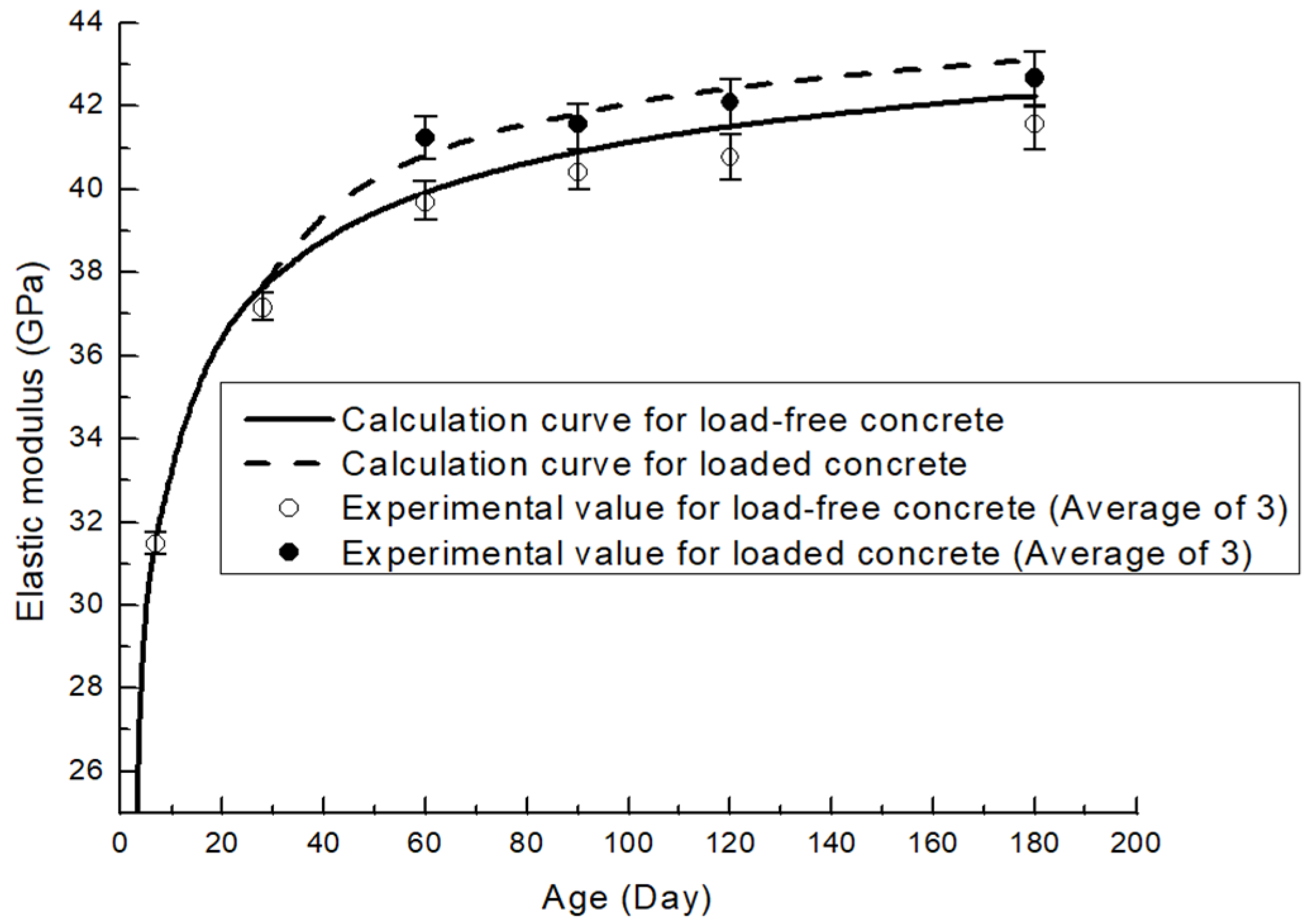

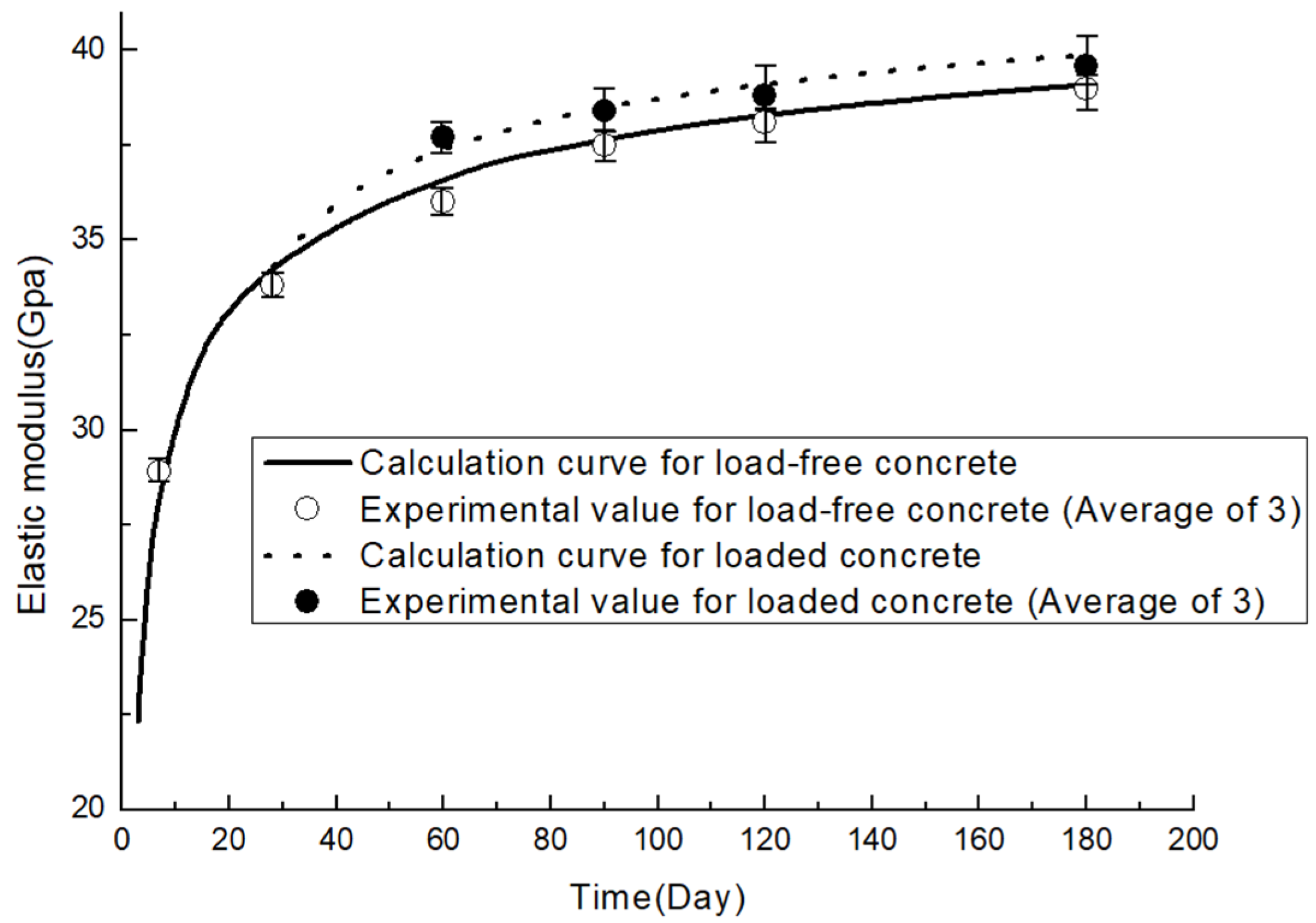

3.2.3. Validation Results

3.3. Parameter Analysis

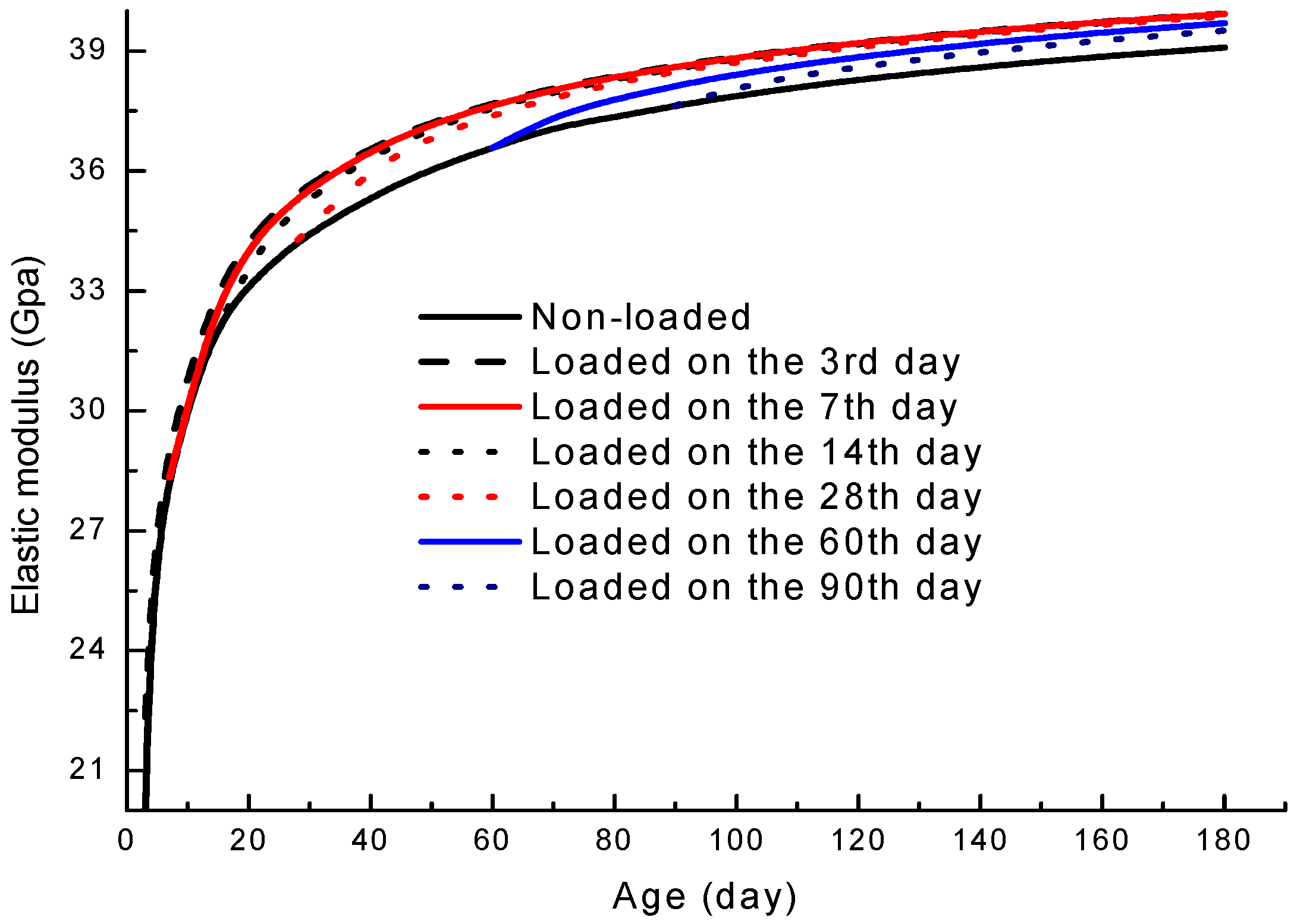

3.3.1. Initial Loading Age

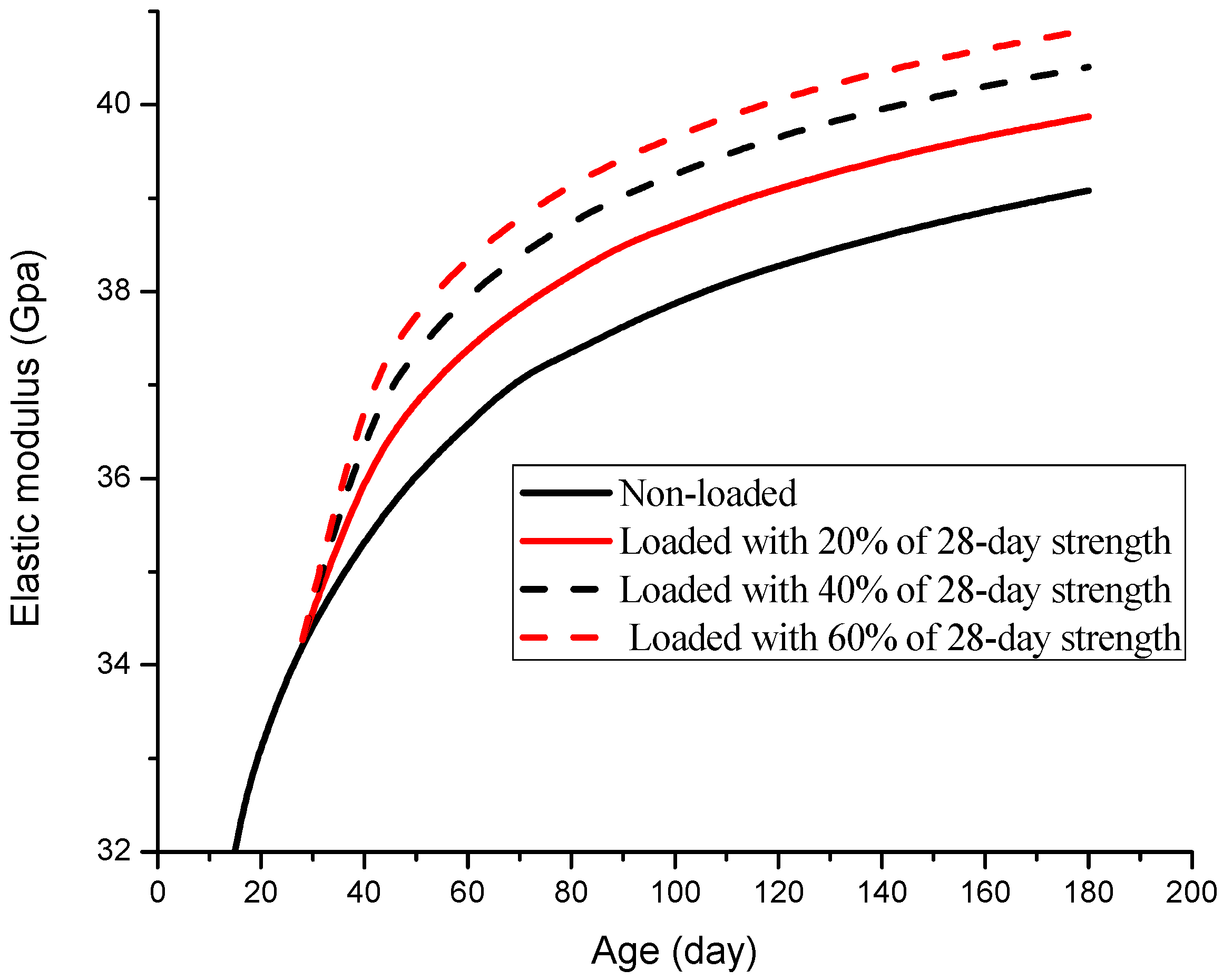

3.3.2. Loading Level

4. Conclusions

- (I)

- Test results have shown a small extra gain in elastic modulus for loaded concrete of up to 5% of the non-loaded concrete.

- (II)

- The established model has been proven to be suitable for predicting the elastic modulus of concrete under sustained load.

- (III)

- Parameter analyses based on the model show that concrete loaded at earlier ages tends to have a higher elastic modulus than its counterparts at later ages; moreover, concrete with a higher load level has a larger extra elastic modulus gain.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Le Chaelier, H. Observations Préliminaires au Sujet de la Décomposition des Ciments à la Mer; NII: Tokyo, Japan, 1907; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, R.E.; Davis, H.E. Flow of concrete under the action of sustained loads. J. Proc. 1931, 27, 837–901. [Google Scholar]

- Price, W.H. Factors influencing concrete strength. ACI J. 1951, 47, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, R. Investigation into the strength of concrete under sustained load. RILEM Bull. 1959, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch, H. Researches toward a general flexural theory for structural concrete. ACI J. 1960, 32, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Roll, F. Long-time creep-recovery of highly stressed concrete cylinders. ACI J. Spec. Publ. 1964, 9, 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, B.P.; Ash, J.E. Some factors influencing the long term strength of concrete. Mater. Struct. 1970, 3, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.P.; Chandra, S. Fracture of concrete subjected to cyclic and sustained loading. J. Proc. 1970, 67, 816–827. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenthal, A.M.; Roll, F. Creep and creep recovery of concrete under high compressive stress. J. Proc. 1958, 54, 1111–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho, A.S. A contribution to the mechanism of concrete creep. Mater. Struct. 1977, 10, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.J. 30-year creep and shrinkage of concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 2005, 57, 545–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imoh, U.U.; Habashneh, M.; Kaine, S.C.; Babafemi, A.J.; Hassan, R.; Rad, M.M. Metakaolin-Enhanced Laterite Rock Aggregate Concrete: Strength Optimization and Sustainable Cement Replacement. Buildings 2025, 15, 4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imoh, U.U.; Apata, A.C.; Rad, M.M. Performance of Concrete Incorporating Waste Glass Cullet and Snail Shell Powder: Workability and Strength Characteristics. Buildings 2025, 15, 2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Liu, M.H.; Xie, H.B.; Liu, Y.P. A strength developing model of concrete under sustained loads. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 105, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yang, D.; Tao, Y.; Shi, J. Machine Learning Assisted Prediction and Analysis of In-Plane Elastic Modulus of Hybrid Hierarchical Square Honeycombs. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 19, 111736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, P.; Song, T.; He, B.; Li, W.; Peng, Y. Elastic Modulus Prediction of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete with Different Machine Learning Models. Buildings 2024, 14, 3184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Larrard, F. Concrete Mixture Proportioning: A Scientific Approach; E. & F.N. Spon: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ulm, F.J.; Coussy, O. Strength growth as chemo-plastic hardening in early age concrete. J. Eng. Mech. 1996, 122, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulm, F.J.; Constantinides, G.; Heukamp, F.H. Is concrete a poromechanics materials—A multiscale investigation of poroelastic properties. Mater. Struct. 2004, 37, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, B.; Hellmich, C.; Eberhardsteiner, J. Spherical and acicular representation of hydrates in a micromechanical model for cement paste: Prediction of early-age elasticity and strength. Acta Mech. 2009, 203, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.Y.; Park, K.B. Analysis of compressive strength development of concrete containing high volume fly ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 98, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.B.; Noguchiand, T.; Plawsky, J. Modeling of hydration reactions using neural networks to predict the average properties of cement paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazant, Z.P.; Hauggaard, A.B. Microprestress-solidification theory for concrete creep I: Aging and drying effects. J. Eng. Mech. 1997, 123, 1188–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisschop, J. Does applied stress affect Portland cement hydration. In Proceedings of the 13th International Congress of Chemical Concrete, Madrid, Spain, 3–8 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson, M.S. Nonhydrostatic thermodynamics and its geologic applications. Rev. Geophys. 1973, 11, 355–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentz, D.P. A Three-Dimensional Cement Hydration and Microstructure Program. I. Hydration Rate, Heat of Hydration and Chemical Shrinkage; NISTIR 5756; U.S. Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 1995.

- Mori, T.; Tanaka, K. Average stress in matrix and average elastic energy of materials with misfitting inclusions. Acta Metall. 1973, 21, 571–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wang, Y. Damage Constitutive Model of Fly-Ash Concrete under Freeze-Thaw Cycles. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2012, 24, 1165–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 50081-2002; Standard for Test Method of Mechanical Properties on Ordinary Concrete. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2003.

- Lam, L.; Wong, Y.L.; Poon, C.S. Degree of hydration and gel/space ratio of high-volume fly ash/cement systems. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.E. Strength and Deformation Characteristics of Plain Concrete Subject to High Repeated and Sustained Loads; Civil Engineering Studies SRS-372; University of Illinois: Champaign, IL, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Acker, P. Micromechanical analysis of creep and shrinkage mechanisms. In Creep, Shrinkage and Durability Mechanics of Concrete and Other Quasi-Brittle Materials, Proceedings of the 6th International Conference CONCREEP@MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA, 20–22 August 2001; Ulm, F.-J., Bažant, Z., Wittmann, F., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, J.; Nantasetphong, W.; Amirkhizi, A.V.; Nemat-Nasser, S. Ultrasonic properties of fly ash/polyurea composites. Mater. Des. 2016, 89, 264–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinides, G.; Ulm, F.J. The effect of two types of C-S-H on the elasticity of cement-based materials: Results from nanoindentation and micromechanical modeling. Cem. Concr. Res. 2004, 34, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| C3S | C2S | C3A | C4AF |

|---|---|---|---|

| 54.7 | 19.2 | 7.1 | 14.0 |

| CaO | SiO2 | AI2O3 | Fe2O3 | MgO | Na2O | K2O | MnO | TiO2 | P2O5 | SO3 | L.O.L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4.35 | 44.26 | 33.12 | 4.39 | 0.78 | 0.45 | 1.71 | 0.05 | 1.41 | 0.73 | 0.31 | 4.08 |

| Type | Cement (kg) | Sand (kg) | Detritus (kg) | Water (kg) | Fly-Ash (kg) | Superplastizer (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 304 | 729 | 1189 | 152 | 76 | 3.8 |

| B | 228 | 729 | 1189 | 152 | 152 | 3.8 |

| Specimen Group | Fly-Ash Replacement | Number of Specimens | Testing Age (Day) |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 20% | 18 | 7, 28, 60, 90, 120, 180 |

| B1 | 40% | 18 | 7, 28, 60, 90, 120, 180 |

| A2 | 20% | 12 | 60, 90, 120, 180 |

| B2 | 40% | 12 | 60, 90, 120, 180 |

| Group | Fly-Ash Replacement | Testing Age (Day) | Elastic Modulus (Average of 3, GPa) | Standard Deviation (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 20% | 7 | 31.46 | 0.44 |

| 28 | 37.15 | 0.52 | ||

| 60 | 39.68 | 0.58 | ||

| 90 | 40.41 | 0.75 | ||

| 120 | 40.78 | 0.79 | ||

| 180 | 41.57 | 0.84 | ||

| B1 | 40% | 7 | 28.93 | 0.43 |

| 28 | 33.86 | 0.47 | ||

| 60 | 36.05 | 0.52 | ||

| 90 | 37.51 | 0.61 | ||

| 120 | 38.11 | 0.66 | ||

| 180 | 39.07 | 0.68 | ||

| A2 | 20% | 60 | 41.24 | 0.72 |

| 90 | 41.56 | 0.88 | ||

| 120 | 42.10 | 0.93 | ||

| 180 | 42.67 | 1.05 | ||

| B2 | 40% | 60 | 37.76 | 0.69 |

| 90 | 38.42 | 0.82 | ||

| 120 | 38.89 | 0.87 | ||

| 180 | 39.63 | 0.96 |

| (cm3/mol) | (cm3/mol) | (MPa) | (MPa) | (MPa) | (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 73.2 | 67.5 | 10.4 | 13.2 | 0.1 | 297 |

| (GPa) | (GPa) | (GPa) | (GPa) | (cm3 Mpa K−1 mol−1) | |

| 116.7 | 48.9 | 53.8 | 35.15 | 8.314 | |

| Phase | Bulk Modulus (GPa) | Shear Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinker [32] | 116.7 | 53.8 |

| Fly-Ash [33] | 48.9 | 35.15 |

| Hydrates [34] | 14.3 | 8.7 |

| Group | Testing Date (Day) | Experimental Data (GPa) | Model Calculation (GPa) | Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 7 | 31.46 | 31.89 | 1.37 |

| 28 | 37.15 | 37.71 | 1.51 | |

| 60 | 39.68 | 39.93 | 0.63 | |

| 90 | 40.41 | 40.90 | 1.21 | |

| 120 | 40.78 | 41.50 | 1.77 | |

| 180 | 41.57 | 42.26 | 1.66 | |

| B1 | 7 | 28.93 | 28.52 | −1.31 |

| 28 | 33.86 | 34.27 | 1.39 | |

| 60 | 36.05 | 36.58 | 1.61 | |

| 90 | 37.51 | 37.63 | 0.35 | |

| 120 | 38.11 | 38.28 | 0.47 | |

| 180 | 39.07 | 39.08 | 0.21 | |

| A2 | 60 | 41.24 | 40.83 | −0.99 |

| 90 | 41.56 | 41.79 | 0.55 | |

| 120 | 42.10 | 42.42 | −0.82 | |

| 180 | 42.67 | 43.10 | −1.10 | |

| B2 | 60 | 37.76 | 37.40 | −0.79 |

| 90 | 38.42 | 38.50 | 0.26 | |

| 120 | 38.89 | 39.11 | 0.79 | |

| 180 | 39.63 | 39.87 | 0.68 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Z.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, S. Prediction of the Time-Dependent Elastic Modulus of Fly-Ash Concrete Under Sustained Loads. Materials 2026, 19, 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030559

Chen Z, Liu M, Zhang Y, Jia S. Prediction of the Time-Dependent Elastic Modulus of Fly-Ash Concrete Under Sustained Loads. Materials. 2026; 19(3):559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030559

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Zhuoran, Minghui Liu, Yurong Zhang, and Siyi Jia. 2026. "Prediction of the Time-Dependent Elastic Modulus of Fly-Ash Concrete Under Sustained Loads" Materials 19, no. 3: 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030559

APA StyleChen, Z., Liu, M., Zhang, Y., & Jia, S. (2026). Prediction of the Time-Dependent Elastic Modulus of Fly-Ash Concrete Under Sustained Loads. Materials, 19(3), 559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030559