Al-Induced Unusual Grain Growth in Ni-Co-Cr Multi-Principal Element Alloys

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ding, J.; Yu, Q.; Asta, M.; Ritchie, R.O. Tunable stacking fault energies by tailoring local chemical order in CrCoNi medium-entropy alloys. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 8919–8924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laplanche, G.; Kostka, A.; Reinhart, C.; Hunfeld, J.; Eggeler, G.; George, E.P. Reasons for the superior mechanical properties of medium-entropy CrCoNi compared to high-entropy CrMnFeCoNi. Acta Mater. 2017, 128, 292–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, D.; An, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Lu, S.; Munroe, P.; Zhang, S.; Liao, X.; Zhu, T.; et al. Unraveling dual phase transformations in a CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 2021, 215, 117112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Hilhorst, A.; Idrissi, H.; Jacques, P.J. Potential TRIP/TWIP coupled effects in equiatomic CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy. Acta Mater. 2022, 234, 118049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Asta, M.; Zhao, S.; Ritchie, R.O.; Ding, J.; Minor, A.M.; Chong, Y. Short-range order and its impact on the CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy. Nature 2020, 581, 283–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Jiang, P.; Yuan, F.; Wu, X. Chemical medium-range order in a medium-entropy alloy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.-J.; Sheng, H.; Ma, E. Strengthening in multi-principal element alloys with local-chemical-order roughened dislocation pathways. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gludovatz, B.; Hohenwarter, A.; Thurston, K.V.S.; Bei, H.; Wu, Z.; George, E.P.; Ritchie, R.O. Exceptional damage-tolerance of a medium-entropy alloy CrCoNi at cryogenic temperatures. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Yu, Q.; Kabra, S.; Jiang, M.; Forna-Kreutzer, P.; Zhang, R.; Payne, M.; Walsh, F.; Gludovatz, B.; Asta, M.; et al. Exceptional fracture toughness of CrCoNi-based medium- and high-entropy alloys at 20 kelvin. Science 2022, 378, 978–983. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Seol, J.B.; Bae, J.W.; Li, Z.; Han, J.C.; Kim, J.G.; Raabe, D.; Kim, H.S. Boron doped ultrastrong and ductile high-entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2018, 151, 366–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.S.; Silva, A.K.d.; Ikeda, Y.; Körmann, F.; Lu, W.; Choi, W.S.; Gault, B.; Ponge, D.; Neugebauer, J.; Raabe, D. Ultrastrong medium-entropy single-phase alloys designed via severe lattice distortion. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, e1807142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.-E.; Kim, Y.-K.; Yang, S.; Lee, K.-A. Interstitial carbon content effect on the microstructure and mechanical properties of additively manufactured NiCoCr medium-entropy alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 918, 165601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustianingrum, M.P.; Yoshida, S.; Tsuji, N.; Park, N. Effect of aluminum addition on solid solution strengthening in CoCrNi medium-entropy alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 781, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, S.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, W.; Peng, F.; Li, Q.; Yang, T.; Wu, C.-Y.; Wei, D.; Chou, Y.-C.; et al. Achieving superb strength in single-phase FCC alloys via maximizing volume misfit. Mater. Today 2023, 63, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yan, D.; Yuan, F.; Jiang, P.; Ma, E.; Wu, X. Dynamically reinforced heterogeneous grain structure prolongs ductility in a medium-entropy alloy with gigapascal yield strength. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 7224–7229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, E.; Wu, X. Tailoring heterogeneities in high-entropy alloys to promote strength-ductility synergy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, S.; Bhattacharjee, T.; Bai, Y.; Tsuji, N. Friction stress and Hall-Petch relationship in CoCrNi equi-atomic medium entropy alloy processed by severe plastic deformation and subsequent annealing. Scr. Mater. 2017, 134, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathiyamoorthi, P.; Moon, J.; Bae, J.W.; Asghari-Rad, P.; Kim, H.S. Superior cryogenic tensile properties of ultrafine-grained CoCrNi medium-entropy alloy produced by high-pressure torsion and annealing. Scr. Mater. 2019, 163, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Ikeuchi, T.; Bhattacharjee, T.; Bai, Y.; Shibata, A.; Tsuji, N. Effect of elemental combination on friction stress and Hall-Petch relationship in face-centered cubic high / medium entropy alloys. Acta Mater. 2019, 171, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.H.; Wu, Y.; He, J.Y.; Nieh, T.G.; Lu, Z.P. Grain growth and the Hall–Petch relationship in a high-entropy FeCrNiCoMn alloy. Scr. Mater. 2013, 68, 526–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Bei, H.; Otto, F.; Pharr, G.M.; George, E.P. Recovery, recrystallization, grain growth and phase stability of a family of FCC-structured multi-component equiatomic solid solution alloys. Intermetallics 2014, 46, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Lu, D.H.; Liu, X.W.; Liu, F.C.; Yang, Q.; Du, H.; Hu, Q.; Fan, Z.T. Solute segregation effect on grain boundary migration and Hall–Petch relationship in CrMnFeCoNi high-entropy alloy. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, W.; Wu, M.S. Inhibiting the inverse Hall-Petch behavior in CoCuFeNiPd high-entropy alloys with short-range ordering and grain boundary segregation. Scr. Mater. 2022, 221, 114950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Gao, F.; Wang, Y.; Men, H.; Zhou, L. Effect of solutes on grain refinement. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2021, 123, 100809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, F.D.; Svoboda, J. Diffusion of elements and vacancies in multi-component systems. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 60, 338–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, W.-R.; Xie, Z.; Xu, S.; Su, Y.; Yao, X.; Beyerlein, I.J. Effects of lattice distortion and chemical short-range order on the mechanisms of deformation in medium entropy alloy CoCrNi. Acta Mater. 2020, 199, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutor, R.K.; Cao, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Fang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, J.-Z. Phase selection, lattice distortions, and mechanical properties in high-entropy alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2020, 22, 2000466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, F.J.; Hatherly, M. Recrystallization and Related Annealing Phenomena, 2nd. ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

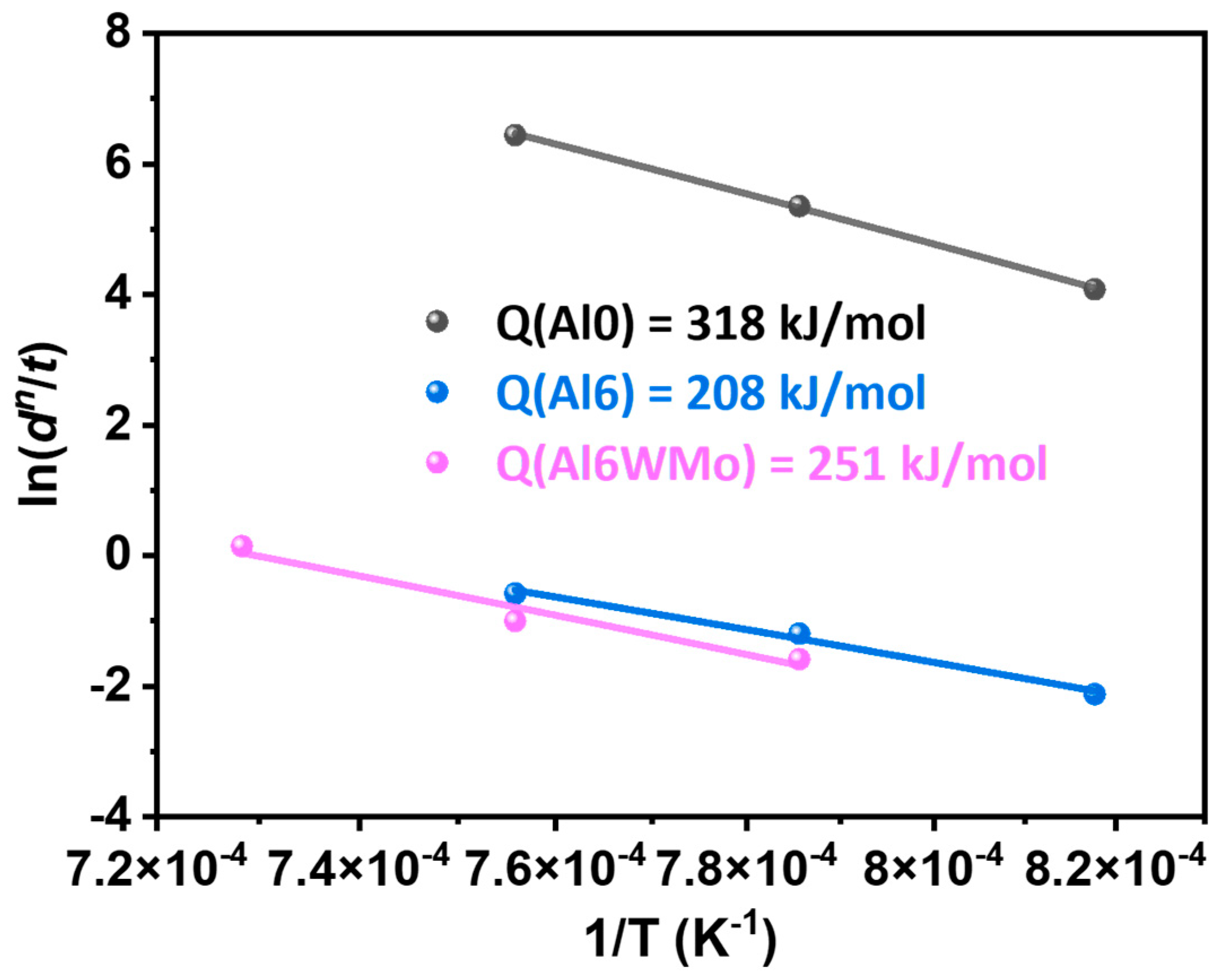

- Gwalani, B.; Salloom, R.; Alam, T.; Valentin, S.G.; Zhou, X.; Thompson, G.; Srinivasan, S.G.; Banerjee, R. Composition-dependent apparent activation-energy and sluggish grain-growth in high entropy alloys. Mater. Res. Lett. 2019, 7, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.Y.; Xue, H.; Liu, G.; Sun, J. Achieving excellent strength-ductility synergy in twinned NiCoCr medium-entropy alloy via Al/Ta co-doping. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 87, 184–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annasamy, M.; Haghdadi, N.; Taylor, A.; Hodgson, P.; Fabijanic, D. Static recrystallization and grain growth behaviour of Al0.3CoCrFeNi high entropy alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 754, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qin, X.Y.; Xiong, W.; Chen, L.; Kong, M.G. Thermal stability and grain growth behavior of nanocrystalline Mg2Si. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 434, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liempt, J.A.M.v. Die berechnung der auflockerungswärme der metalle aus rekristallisationsdaten. Z. Für Phys. 1935, 96, 534–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, J.; Rohrer, G.S.; Rollett, A. Recrystallization and Related Annealing Phenomena; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, R.; Fang, W.; Bai, X.; Xia, C.; Zhang, X.; Yu, H.; Liu, B.; Yin, F. Effects of tungsten additions on the microstructure and mechanical properties of CoCrNi medium entropy alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 790, 732–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.W.; Zeng, L.C.; Du, H.; Liu, X.W.; Wu, Y.; Gong, P.; Fan, Z.T.; Hu, Q.; George, E.P. Tailoring grain growth and solid solution strengthening of single-phase CrCoNi medium-entropy alloys by solute selection. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

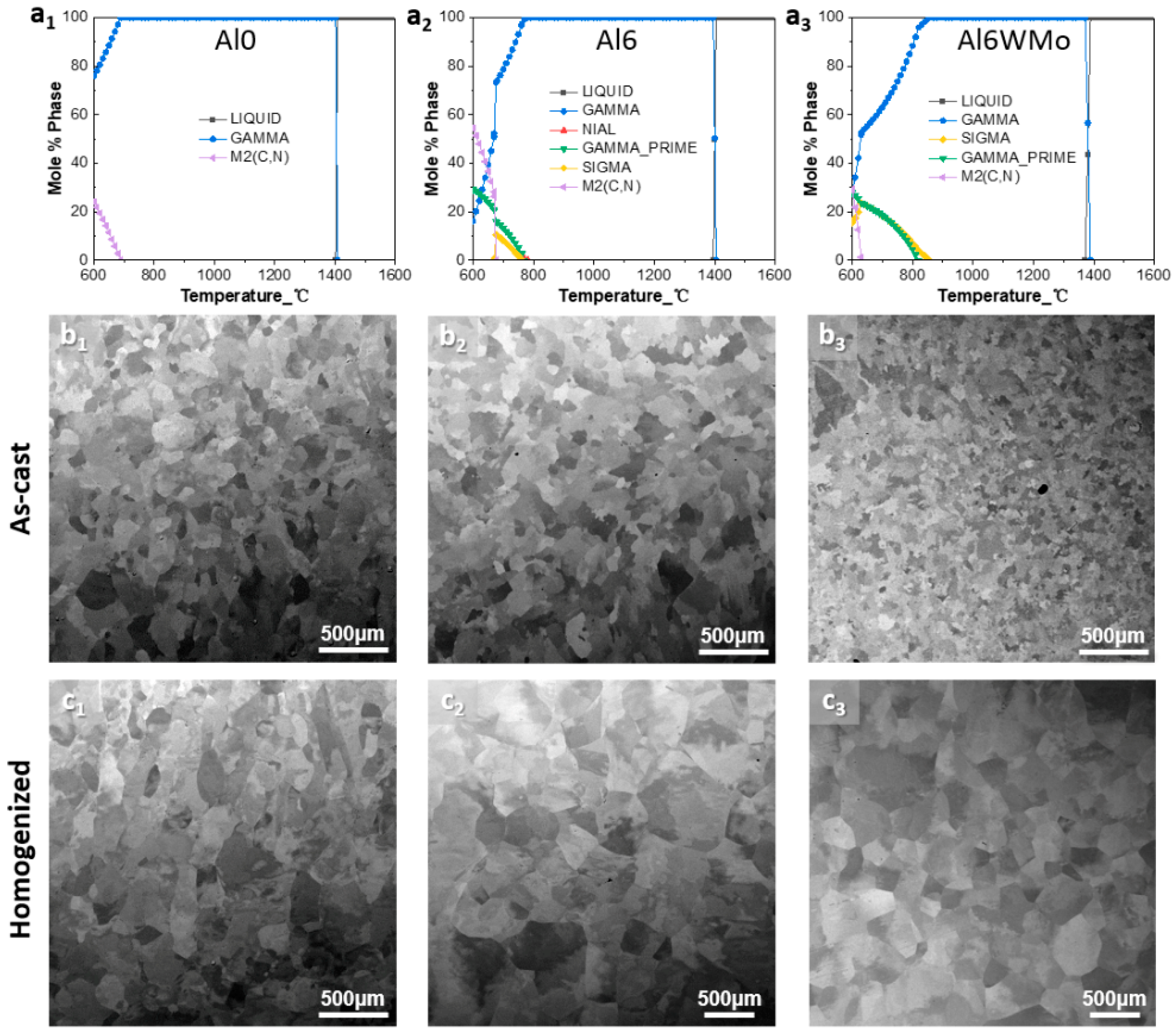

| Alloy | Name | Solid Solution Treatment | Cold Rolling | Recrystallization/Aging Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni33.34Co33.34Cr33.32 | Al0 | 1250 °C/2 h | 70% | 1050 °C/5~120 min |

| 1000 °C/5~120 min | ||||

| 950 °C/5~120 min | ||||

| Ni33.34Co33.34Cr27.32Al6 | Al6 | 1250 °C/2 h | 70% | 1050 °C/5~120 min |

| 1000 °C/5~120 min | ||||

| 950 °C/5~120 min | ||||

| Ni32.34Co32.34Cr27.32Al6W1Mo1 | Al6WMo | 1250 °C/2 h | 70% | 1100 °C/5~120 min |

| 1050 °C/5~120 min | ||||

| 1000 °C/5~120 min |

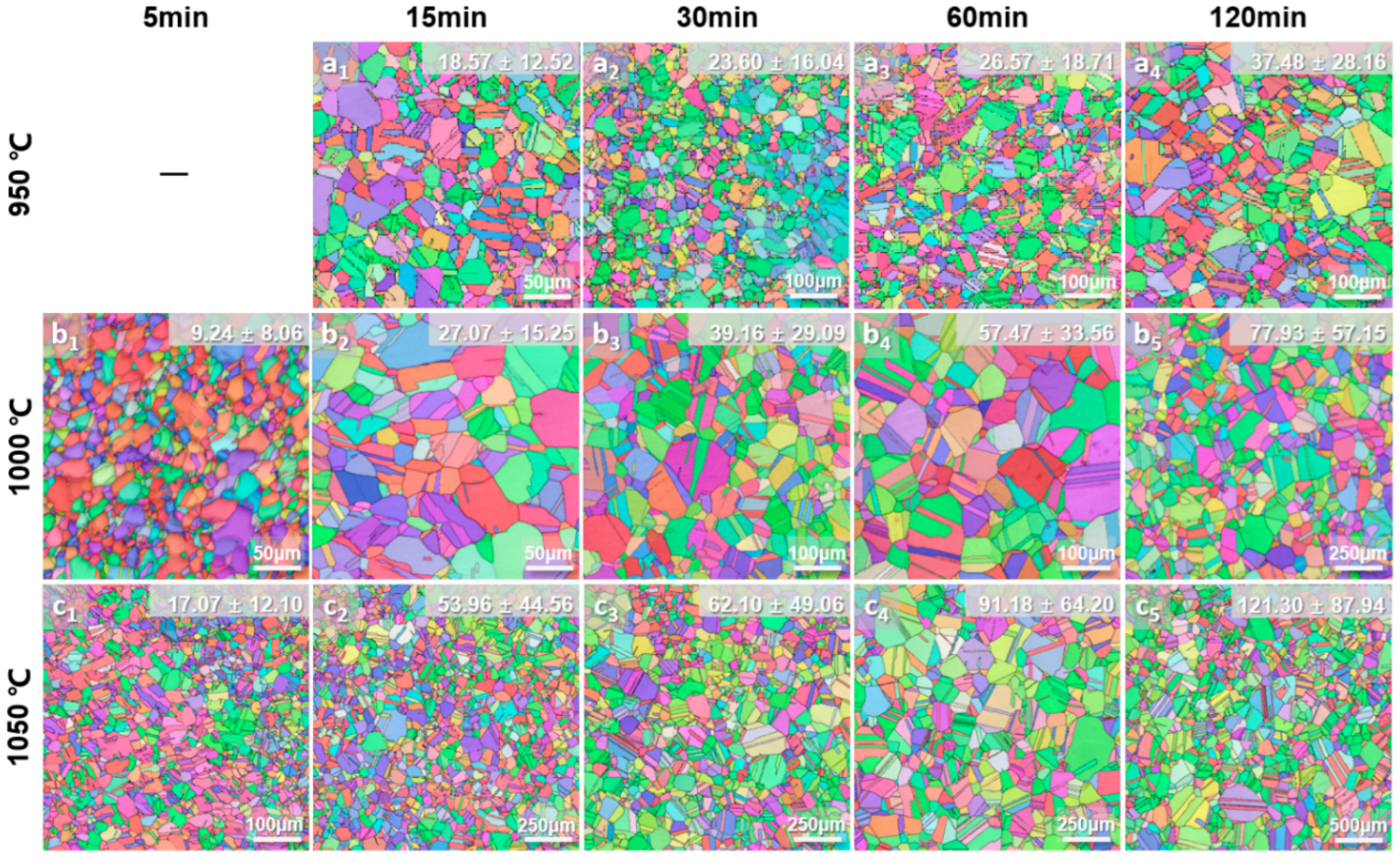

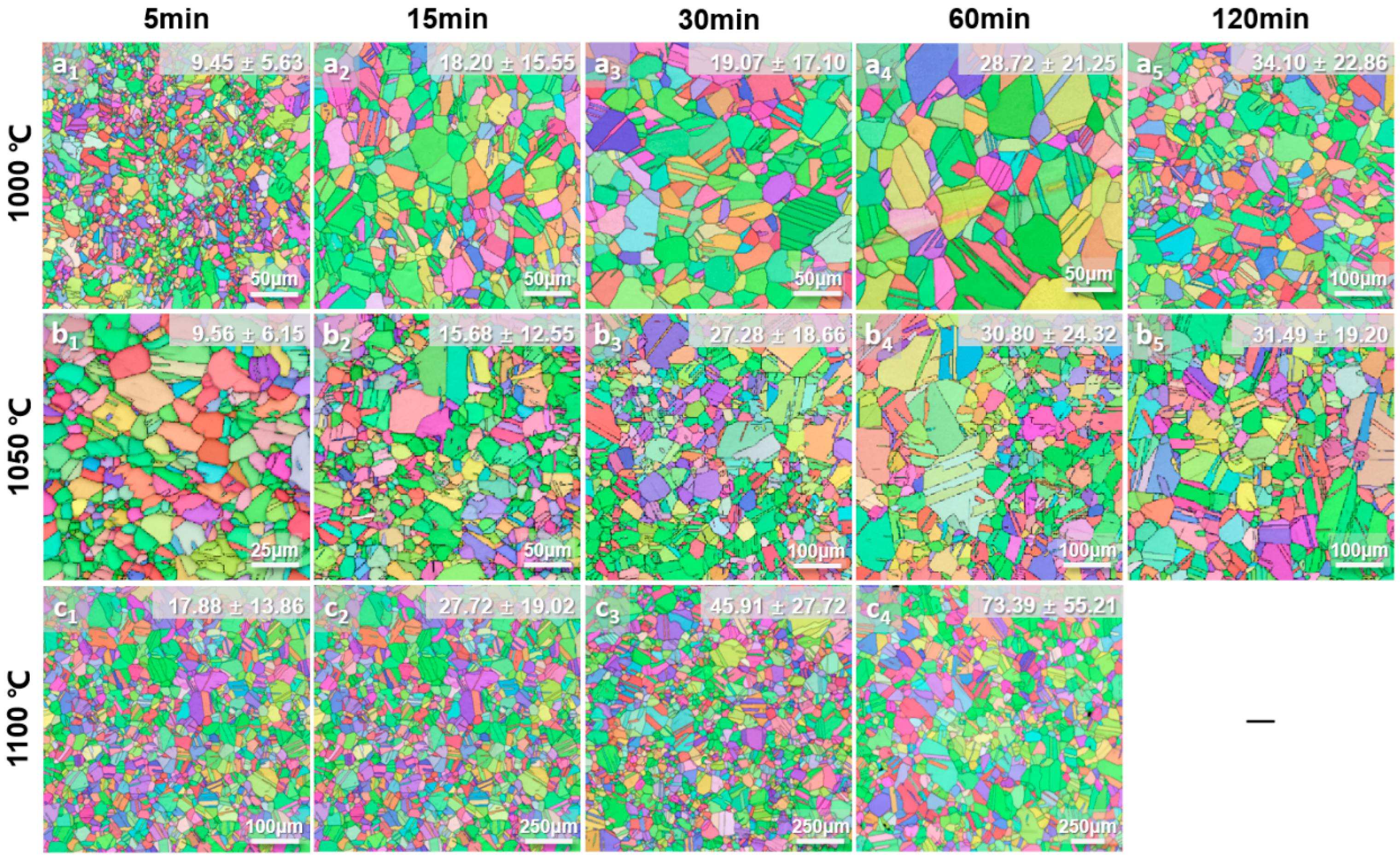

| Temperature/°C | Duration/Min | Grain Size/μm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al0 | Al6 | Al6WMo | ||

| 950 | 15 | 9.34 ± 5.99 | 18.57 ± 12.52 | — |

| 30 | 14.66 ± 11.54 | 23.60 ± 16.04 | — | |

| 60 | 16.80 ± 12.67 | 26.57 ± 18.71 | — | |

| 120 | 17.33 ± 12.81 | 37.48 ± 28.16 | — | |

| 1000 | 5 | 10.78 ± 7.94 | 9.24 ± 8.06 | 9.45 ± 5.63 |

| 15 | 18.03 ± 10.68 | 27.07 ± 15.25 | 18.20 ± 15.55 | |

| 30 | 18.89 ± 13.22 | 39.16 ± 29.09 | 19.07 ± 17.10 | |

| 60 | 19.69 ± 13.00 | 57.47 ± 33.56 | 28.72 ± 21.25 | |

| 120 | 19.98 ± 17.58 | 77.93 ± 57.15 | 34.10 ± 22.86 | |

| 1050 | 5 | 13.94 ± 9.86 | 20.36 ± 13.29 | 9.56 ± 6.15 |

| 15 | 19.78 ± 17.48 | 45.20 ± 34.99 | 15.68 ± 12.55 | |

| 30 | 24.45 ± 14.47 | 63.64 ± 47.57 | 27.28 ± 18.66 | |

| 60 | 25.91 ± 15.96 | 84.54 ± 51.37 | 30.80 ± 24.32 | |

| 120 | 27.70 ± 17.74 | 122.90 ± 86.91 | 31.49 ± 19.20 | |

| 1100 | 5 | — | — | 17.88 ± 13.86 |

| 15 | — | — | 27.72 ± 19.02 | |

| 30 | — | — | 45.91 ± 27.72 | |

| 60 | — | — | 73.39 ± 55.21 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, K.; Wu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Gong, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z. Al-Induced Unusual Grain Growth in Ni-Co-Cr Multi-Principal Element Alloys. Materials 2026, 19, 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030505

Zhou K, Wu S, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Lei X, Wang X, Xu X, Gong W, Li Y, Wang Z. Al-Induced Unusual Grain Growth in Ni-Co-Cr Multi-Principal Element Alloys. Materials. 2026; 19(3):505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030505

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Kexuan, Siqi Wu, Yan Zhou, Yanjun Zhang, Xiaoxin Lei, Xin Wang, Xiaoyong Xu, Wenhao Gong, Yue Li, and Zhijun Wang. 2026. "Al-Induced Unusual Grain Growth in Ni-Co-Cr Multi-Principal Element Alloys" Materials 19, no. 3: 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030505

APA StyleZhou, K., Wu, S., Zhou, Y., Zhang, Y., Lei, X., Wang, X., Xu, X., Gong, W., Li, Y., & Wang, Z. (2026). Al-Induced Unusual Grain Growth in Ni-Co-Cr Multi-Principal Element Alloys. Materials, 19(3), 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19030505