FeSe2-BiSe2-CoSe2 Ternary Heterojunction for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Under pH-Universal

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Characterization

3.2. HER Performance in 0.5 M H2SO4

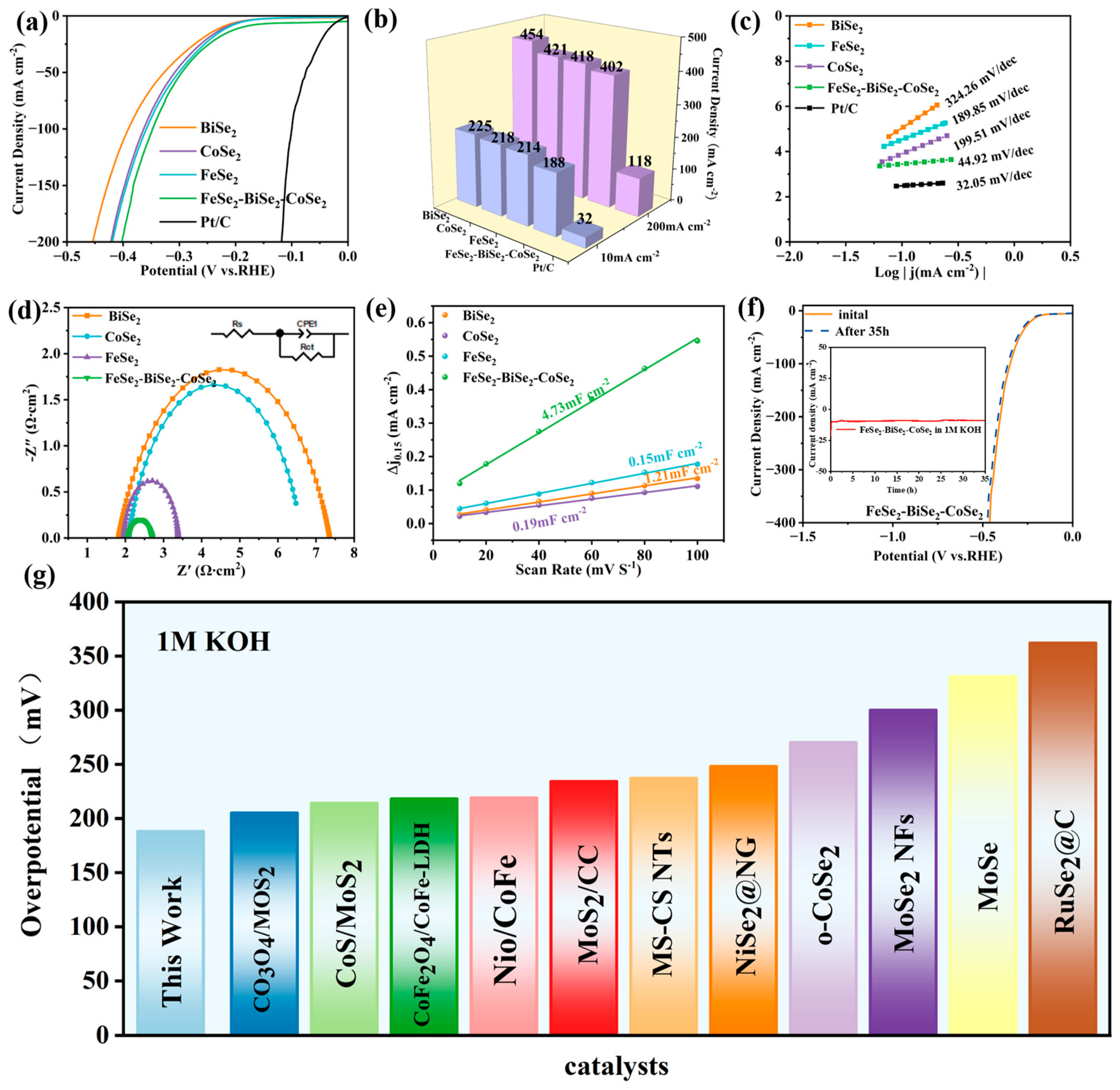

3.3. HER Performance in 1 M KOH

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wu, A.P.; Xie, Y.; Ma, H.; Tian, C.G.; Gu, Y.; Yan, H.J.; Zhang, X.M.; Yang, G.Y.; Fu, H.G. Integrating the active OER and HER components as the heterostructures for the efficient overall water splitting. Nano Energy 2018, 44, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubair, M.; Ul Hassan, M.M.; Mehran, M.T.; Baig, M.M.; Hussain, S.; Shahzad, F. 2D MXenes and their heterostructures for HER, OER and overall water splitting: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 2794–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.S.; Liu, S.Y.; Wei, L.G.; He, H.Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhan, Z.S.; Wang, J.; Li, X.W.; Gou, W.T. One-pot hydrothermal synthesis of bifunctional Co/Mo-rGO efficient electrocatalyst for HER/OER in water splitting. Catal. Lett. 2024, 154, 5294–5302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cui, R.J.; Gao, C.C.; Bian, L.Y.; Pu, Y.; Zhu, X.B.; Li, X.A.; Huang, W. Cation-modulated HER and OER activities of hierarchical VOOH hollow architectures for high-efficiency and stable overall water splitting. Small 2019, 15, 1904688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, J.X.; Zhang, Z.F.; Feng, H.; Zhao, H.W.; Chai, D.F.; Huang, X.M.; Zhang, W.Z.; Zhao, M.; Dong, G.H.; Zang, Y.; et al. P-doped Co-based nanoarray heterojunction with multi-interfaces for complementary HER/OER electrocatalysts towards high-efficiency overall water splitting in alkaline. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 64, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.H.; Wang, L.P.; Yuan, A.J.; Xie, J.; Liu, H.; Zhang, H.J.; Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, L. Synergistic ternary catalysis: NiCo-LDH/Ni3S2/Co9S8@NiFe-LDH-Ov/NF composite catalyst for high-efficiency HER/OER bifunctional water splitting. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1026, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, H.T.; Hoa, V.; Sidra, S.; Mai, M.; Zharnikov, M.; Kim, D. Dual efficiency enhancement in overall water splitting with defect-rich and Ru atom-doped NiFe LDH nanosheets on NiCo2O4 nanowires. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485, 150054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, Z.H.; Xu, Q.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, Y.L.; Liu, K.K.; Lei, S.W.; Zhang, L.X.; Guo, F.B. Coupling interface constructions of clustered Mn-CoFeSe2 derived from CoFe-LDH for efficient overall water splitting. Fuel 2026, 410, 138000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.B.; Cheng, J.; Lei, H.Y.; Sui, Z.H.; Yu, Y.M.; Han, J.L.; Yue, T.J.; Liu, K.K. Transition metal manganese induces structural reorganization of MnxMo1-xSe2 for efficient overall water splitting. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2026, 703, 139203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.N.; Cheng, Z.F.; He, S.; Wu, Z.P.; Zhang, X.D.; Ren, Z.W.; Zong, D.H.; Deng, K.L.; Xi, M.G. Influence of monolayer MoS2 grain boundaries on MoS2 cluster nucleation during layer-by-layer growth of bilayer MoS2. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2026, 715, 164549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.S.; Wang, W.; Shang, X.Y.; Tang, H.; Zulfiqa, S. Solar-driven photocatalytic water oxidation of Ag3PO4/CNTs@MoSe2 ternary composite photocatalyst. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 505, 144613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ren, S.; Xing, X.D.; Yang, J.; Li, J.L.; Yang, J.; Liu, Q.C. Effect of MnO2 crystal types on CeO2@MnO2 oxides catalysts for low-temperature NH3-SCR. J. Environ. Chem Eng. 2022, 10, 108239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.Y.; Cui, W.; Cui, S.X.; Li, G.C.; Han, L. MOF-derived Co(Fe)OOH slab and Co/MoN nanosheet-covered hollow-slab for efficient overall water splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 69368–69378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, P.; Zhao, Z.L. An interfacially engineered Ni2P/Fe2P heterostructure grown on NiFe PBA/NF as a high-efficiency bifunctional electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. Fuel 2026, 413, 138306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.B.; Yu, Y.M.; Sui, Z.H.; Cheng, J.; Li, Y.H.; Wang, X.J.; Duan, J.W.; Lei, S.W.; Liu, K.K. Electronic self-regulation of ternary alloy selenides FeNiCoSe2 for efficient overall water splitting. Fuel 2026, 405, 136679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Yu, Y.M.; Sui, Z.H.; Lei, S.W.; Duan, Q.Y.; Zhao, Y.M.; Liu, K.K.; Zhang, L.X.; Guo, F.B. Transition metal Co-induced phase transition of CoxMo1-x Se2 to promote a hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 2176–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.K.; Cheng, J.; Yu, Y.M.; Sui, Z.H.; Guo, F.B.; Lei, S.W.; Zhang, L.X.; Li, M.; Yun, Y.B. Transition metal Co induce CoSe2/NiWSe2 interface structural reorganization for efficient oxygen evolution reaction and urea oxidation reaction. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 45, 103950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.O.; Moon, H.S.; Hong, I.J.; Lakhera, S.K.; Yong, K.J. Hollow SrTiO3 photocatalyst with spatially separated OER and HER cocatalysts for photocatalytic overall water splitting. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 665, 160298. [Google Scholar]

- Mane, R.S.; Zaroliwalla, D.; Periyasamy, G.; Jha, N. Leafy ZIF-Derived Bi-metallic phosphate-mxene nanocomposites for overall water splitting. Small 2025, 21, 2503228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Zhang, J.Y.; Hu, Y.T.; Wang, L.Q.; Zhang, X.F.; Zhao, B. Ni doped Co-MOF-74 synergized with 2D Ti3C2Tx MXene as an efficient electrocatalyst for overall water-splitting. Catalysts 2024, 14, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Sui, Z.H.; Guo, F.B.; Guo, X.H.; Lei, S.W.; Liu, K.K. Hollow shell-core heterojunction enhances oxygen evolution reaction and urea oxidation reaction of MOF-NiSe2@MoSe2. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 136, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Du, X.Q.; Zhang, X.S.; Wang, Y.H. Ni3S2/MxSy-NiCo LDH (M = Cu, Fe, V, Ce, Bi) heterostructure nanosheet arrays on Ni foam as high-efficiency electrocatalyst for electrocatalytic overall water splitting and urea splitting. Dalton Trans. 2023, 52, 763–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Jiu, H.; Zhang, L.X.; Guo, F.B.; Cheng, J.; Yu, Y.M.; Ma, J.F.; Li, H. Vanadium-doped induced multicomponent oxide NiFeVOX@NF with tremella-like structure for efficient overall water splitting. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 126, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.B.; Zhao, X.Y.; Cheng, J.; Liu, K.K.; Zhang, L.X. NiMOF-derived MoSe2@NiSe2 heterostructure with hollow core-shell for efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 947, 169513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.Y.; Li, C.; Xiong, T.T.; Xie, Y.H.; Luo, F.; Yang, Z.H. Hydrogen spillover in MoOXRh hierarchical nanosheets boosts alkaline HER catalytic activity. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. Energy 2024, 341, 123275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Bai, X.; Xue, H.; Sun, J.; Song, T.S.; Zhang, S.; Qin, L.; Huang, K.K.; He, F.; Wang, Q. MOF-derived hierarchical 3D bi-doped CoP nanoflower eletrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction in both acidic and alkaline media. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 7702–7705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, Y.; Xue, J.W.; Hu, J.J.; Chen, L.J. High-current density alkaline water/seawater splitting by Mo and Fe co-doped Ni3S2: Invariant active sites with accelerated water dissociation kinetics. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. Energy 2025, 361, 124698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.X.; Zhang, Y. Noble metal-free hydrogen evolution catalysts for water splitting. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 5148–5180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.W.; Li, J.; Ou, P.F.; Huang, J.E.; Wen, Z.; Chen, L.X.; Yao, X.; Cai, G.M.; Yang, C.C.; Singh, C.V.; et al. Unusual sabatier principle on high entropy alloy catalysts for hydrogen evolution reactions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.T.; He, W.J.; Shi, S.C.; Yuan, X.K.; Li, J.; Cao, J.L.; Yuan, C.Z.; Liu, X.M. Bamboo fiber-derived carbon support for the immobilization of Pt nanoparticles to enhance hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 684, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, P.Y.; Ni, Z.R.; Zhu, B.C.; Lin, Y.; Yu, J.G. Modulating the d-Band Center Enables Ultrafine Pt3Fe Alloy Nanoparticles for pH-Universal Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2303030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, A.; Kundu, S. Beyond traditional TOF: Unveiling the pitfalls in electrocatalytic active site determination. J. Mater. Chem. A 2025, 13, 39687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.S.; Zhang, Y.H.; Wang, B.Y.; Wang, J.C.; Dai, Y.N.; Hu, L.W.; Lv, X.W.; Dang, J. Significantly enhanced OER and HER performance of NiCo-LDH and NiCoP under industrial water splitting conditions through Ru and Mn bimetallic co-doping strategy. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 494, 153212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Zheng, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Shi, Q.F.; Wan, Y.; Ramakrishna, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, L.Y.; Yokoshima, T.; et al. Unlocking Efficient Hydrogen Production: Nucleophilic Oxidation Reactions Coupled with Water Splitting. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2404806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiang, S.H.; Li, Z.Y.; He, S.Q.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, X.; Yuan, A.H.; Zou, J.S.; Wu, J.C.; Qiao, Y.X. Modulating electronic structure of CoS2 nanorods by Fe doping for efficient electrocatalytic overall water splitting. Nano Energy 2025, 134, 110564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Urrego-Ortiz, R.; Liao, N.; Calle-Vallejo, F.; Luo, J.S. Rationally designed Ru catalysts supported on TiN for highly efficient and stable hydrogen evolution in alkaline conditions. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 6391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.J.; Wei, Y.; Wang, M.K.; Shen, Y. The future of alkaline water splitting from the perspective of electrocatalysts-seizing today’s opportunities. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2025, 522, 216190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.Y.; Liu, D.; Zhao, P.J.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.X.; Oropeza, F.E.; Gorni, G.; Barawi, M.; García-Tecedor, M.; O’Shea, V.A.D.; et al. Dynamic restructuring of nickel sulfides for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.Y.; He, S.Q.; Qiao, Y.X.; Yuan, A.H.; Wu, J.C.; Zhou, H. Interfacial engineering of heterostructured CoP/FeP nanoflakes as bifunctional electrocatalyts toward alkaline water splitting. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 679, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.X.; Wang, J.M.; Liu, G.M.; Weiss, C.M.; Liu, D.Q.; Chen, Y.P.; Xia, L.X.; Zhou, P.; Gao, M.X.; Liu, Y.F.; et al. A strongly coupled Ru-CrOx cluster-cluster heterostructure for efficient alkaline hydrogen electrocatalysis. Nat. Catal. 2024, 7, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.L.; Jiao, Y.; Zou, X.Y.; Guo, Y.C.; Li, W.H.; Ai, T.T. P vacancy-induced electron redistribution and phase reconstruction of CoFeP for overall water splitting at industrial-level current density. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2025, 12, 2678–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.X.; Cui, J.X.; Li, Z.F.; Yang, C.L.; Dong, W.W.; Li, K.; Ma, Y.Y.; Nan, Z. Extraordinary Hydrogen Evolution and Oxygen Evolution Reaction Activity from PPy@FeCo-LDH/NF Bifunctional Electrocatalyst in Alkaline Solution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2024, 171, 086502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.J.; Huang, Y.; Zhu, J.K.; Zhao, Z.Y.; Zhao, J.B.; Zhang, J.J. Cobalt vanadate nano/microrods as high-efficiency dual-functional electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution and urea-assisted alkaline oxygen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 88, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.X.; Cong, X.; Wu, S.S.; Wu, J.B.; Bao, Y.F.; Cao, M.F.; Wu, L.W.; Lin, M.L.; Wang, X.; Tan, P.H.; et al. Visualizing the structural evolution of individual active sites in MoS2 during electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Catal. 2024, 7, 646–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.M.; Xie, Y.H.; Yu, Y.J.; Chen, Y.Z.; Liu, Q.T.; Bao, H.F.; Luo, F.; Pan, S.Y.; Yang, Z.H. Electronic Metal-Support Interaction Induces Hydrogen Spillover and Platinum Utilization in Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Angew. Chem. 2025, 64, 202413471. [Google Scholar]

- Sui, Z.H.; Xu, Q.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, K.K.; Lei, S.W.; Zhang, L.X.; Guo, F.B. Interfacial electronic structure regulation of MoSe2-NiSe2-FeSe2 ternary heterojunction for pH-universal hydrogen evolution reaction. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2026, 207, 153520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Z.X.; Liu, X.E. MoS2/CoB with Se doping on carbon cloth to drive overall water-splitting in an alkaline electrolyte. Sustain. Energ. Fuels 2020, 4, 5036–5041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.F.; Shen, Q.H.; Du, C.C.; Hong, M.; Yang, Y.X.; Zhang, X.H.; Chen, J.H. Enriched Se vacancies engineering of RuSe2 induced by low-valence Cu doping for promoting hydrogen evolution and coupling power generation. Fuel 2024, 361, 130752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Jian, C.Y.; Hong, W.T.; Cai, Q.; Liu, W. Tuning the electron status of urchin-like CoS2 nanowires by selenium doping toward highly efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. Mater. Lett. 2019, 257, 126673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.T.; Zhang, L.L.; Zhou, D.N.; Xiong, C.L.; Zhao, Y.F.; Chen, W.X.; Xiang, X.; Shang, H.S.; Zhang, B. Construction of interconnected NiO/CoFe alloy nanosheets for overall water splitting. Renew. Energy 2022, 194, 459–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Xiang, J.Y.; Wen, F.S.; Song, L.Z.; Mu, C.P.; Xu, D.Y.; Hao, C.X.; Liu, Z.Y. Microwave synthesized three-dimensional hierarchical nanostructure CoS2/MoS2 growth on carbon fiber cloth: A bifunctional electrode for hydrogen evolution reaction and supercapacitor. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 212, 941–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.F.; Li, H.Y.; Li, Y.Y.; Liu, J.L.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Hierarchical CoS/MoS2 and Co3S4/MoS2/Ni2P nanotubes for efficient electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution in alkaline media. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 25410–25419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthurasu, A.; Maruthapandian, V.; Kim, H.Y. Metal-organic framework derived Co3O4/MoS2 heterostructure for efficient bifunctional electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reaction and hydrogen evolution reaction. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. Energy 2019, 248, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yang, C.H.; Sheng, M.H.; Yin, X.T.; Que, W.X. Synergistically coupling phosphorus-doped molybdenum carbide with MXene as a highly efficient and stable electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 12990–12998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.X.; Yu, B.; Hu, Y.; Wang, X.Q.; Yang, D.X.; Chen, Y.F. Core-shell structure of NiSe2 nanoparticles@nitrogen-doped graphene for hydrogen evolution reaction in both acidic and alkaline media. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 20463–20473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.Q.; Li, P.; Rui, K.; Chen, Y.P.; Dou, S.X.; Sun, W.P. CoSe2/MoSe2 heterostructures with enriched water adsorption/dissociation sites towards enhanced alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Chem.-Eur. J. 2018, 24, 11158–11165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.Z.; Xu, K.; Tao, S.; Zhou, T.P.; Tong, Y.; Ding, H.; Zhang, L.D.; Chu, W.S.; Wu, C.Z.; Xie, Y. Phase-transformation engineering in cobalt diselenide realizing enhanced catalytic activity for hydrogen evolution in an alkaline medium. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 7527–7532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Huang, W.J.; Gong, Q.F.; Liu, C.H.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.G.; Dai, H.J. Ultrathin WS2 nanoflakes as a high-performance electrocatalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit. 2014, 53, 7860–7863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.W.; Brüller, S.; Dong, R.H.; Zhang, J.; Feng, X.L.; Müllen, K. Molecular metal-Nx centres in porous carbon for electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, W.J.; Feng, Y.; Li, Z.; Yang, W.Q.; Cheng, C.Q.; Shi, Z.Z.; Yin, P.F.; Shen, G.R.; Yang, J.; Dong, C.K.; et al. Strain-activated copper catalyst for pH-Universal hydrogen evolution reaction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 2112367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.L.; Ji, S.J.; Xue, H.G.; Suen, N.T. HER activity of MxNi1-x (M = Cr, Mo and W; x ≈ 0.2) alloy in acid and alkaline media. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 17533–17539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Catalyst Category | Representative Materials | Principal Advantages | Principal Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Two-dimensional transition metal dichalcogenide | MoS2 | High intrinsic activity, high stability | Poor electrical conductivity, limited active sites |

| Two-dimensional transition metal MSe2 | MoSe2 | Highly conductive, intrinsically highly active | Relatively poor stability, difficult to prepare |

| Transition metal oxides | MnO2 | Non-precious metals are low in cost and diverse in variety. | Low specific surface area, poor electrical conductivity |

| Transition metal nitrides | MoN | Excellent electrical conductivity, high stability | The surface is prone to oxidation and the high-temperature synthesis conditions are demanding. |

| Transition metal phosphides | Ni2P | Excellent electrical conductivity, high HER activity | Phosphorus readily leaches or oxidizes during reactions |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, L.; Cui, Y.; He, Q.; Liu, K. FeSe2-BiSe2-CoSe2 Ternary Heterojunction for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Under pH-Universal. Materials 2026, 19, 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020430

Guo L, Cui Y, He Q, Liu K. FeSe2-BiSe2-CoSe2 Ternary Heterojunction for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Under pH-Universal. Materials. 2026; 19(2):430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020430

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Lili, Yang Cui, Qiusheng He, and Kankan Liu. 2026. "FeSe2-BiSe2-CoSe2 Ternary Heterojunction for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Under pH-Universal" Materials 19, no. 2: 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020430

APA StyleGuo, L., Cui, Y., He, Q., & Liu, K. (2026). FeSe2-BiSe2-CoSe2 Ternary Heterojunction for Efficient Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Under pH-Universal. Materials, 19(2), 430. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19020430