Advanced Numerical Modeling of Powder Bed Fusion: From Physics-Based Simulations to AI-Augmented Digital Twins

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Novelty and Significance

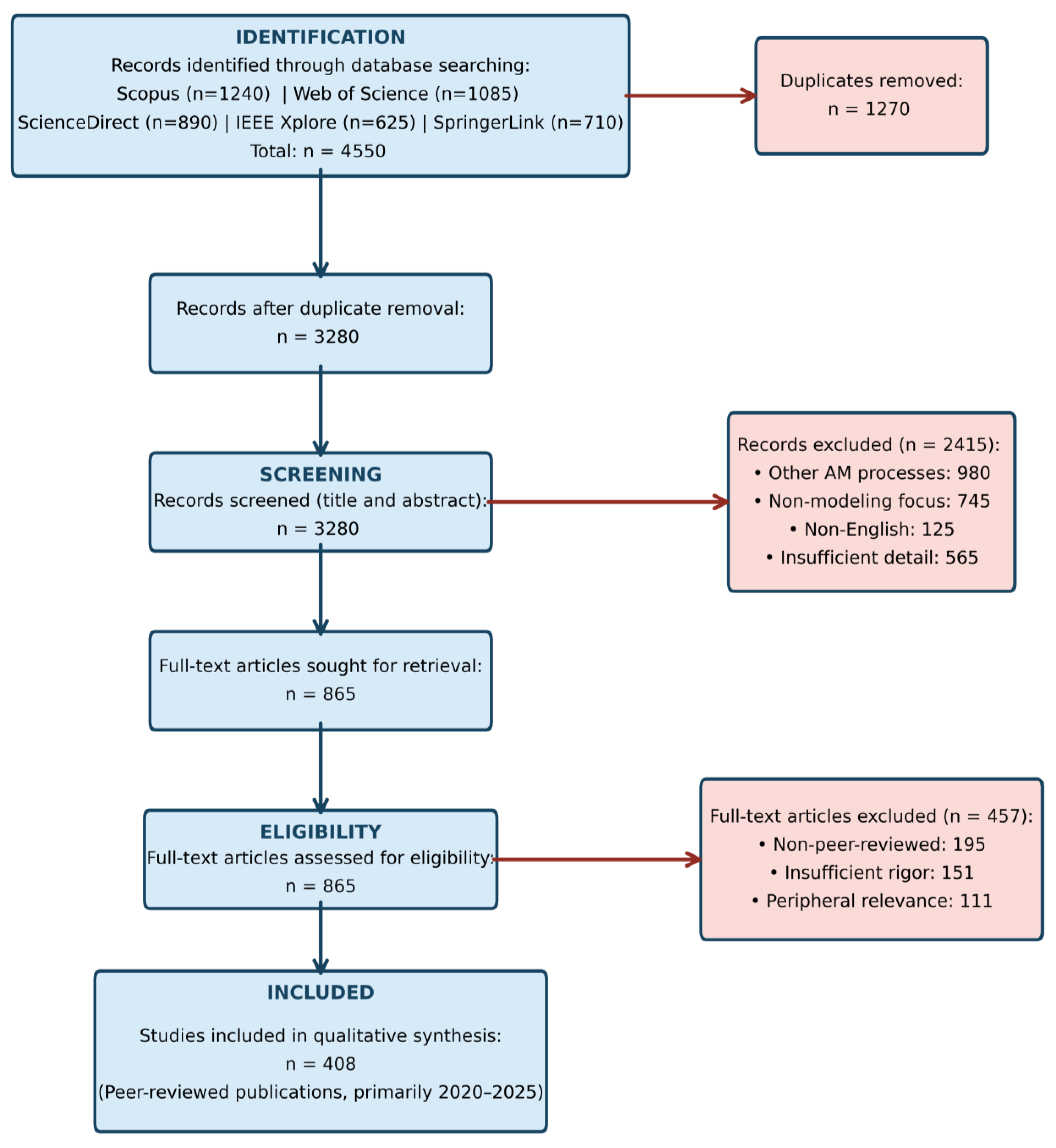

1.2. Review Method

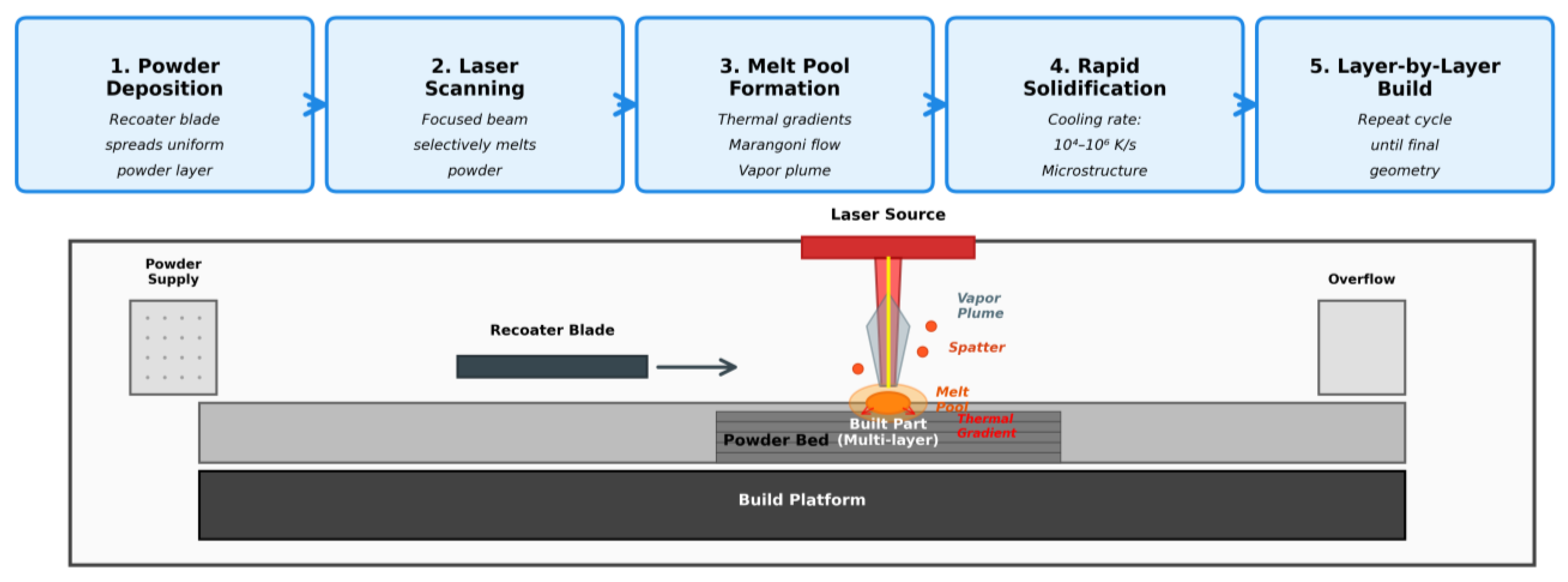

2. Powder Bed Fusion in Materials Processing

- Solid-state sintering: Mainly applied for consolidating ceramic powders;

- Chemically induced binding: Not commonly used in commercial equipment, but it can be a feasible consolidation mechanism for polymers, metals, and ceramics;

- Liquid phase sintering: Partial melting, the main mechanism in SLS for glasses, polymers, and ceramics;

- Full melting: The basic mechanism of the SLM.

- High precision and excellent surface finish: PBF processes produce parts with fine details and smoother surfaces compared to FDM or other methods without extensive post-processing, and are capable of achieving tight tolerances and intricate geometries;

- Complex geometries and internal structures: Processes are highly complex, organic, and has hollow internal features, supporting the creation of lightweight structures such as lattices and topology optimizations;

- Material diversity: Processes include high-performance alloys such as titanium, nickel-based superalloys, aluminum, and steels, enabling the production of functional, load-bearing, and wear-resistant parts in metals, as well as polymers, ceramics, glasses, and composites;

- Suitable for functional and end-use parts: The technology has high mechanical properties, enabling the rapid production of tooling, aerospace parts, medical implants, and customized components;

- Less support material required: Unlike FDM or SLA, PBF generally does not require extensive support structures because the powders themselves support overhangs and complex features during build;

- The process goes through layer-by-layer material consolidation, especially in metal PBF processes such as SLM and EBM;

- The process is capable of producing multiple parts simultaneously in a single build cycle;

- Reduced waste and material efficiency: Only the material in the powder bed is melted or sintered, so excess powder can often be recycled, reducing material waste.

3. Physics-Driven Simulation Throughout the PBF Workflow

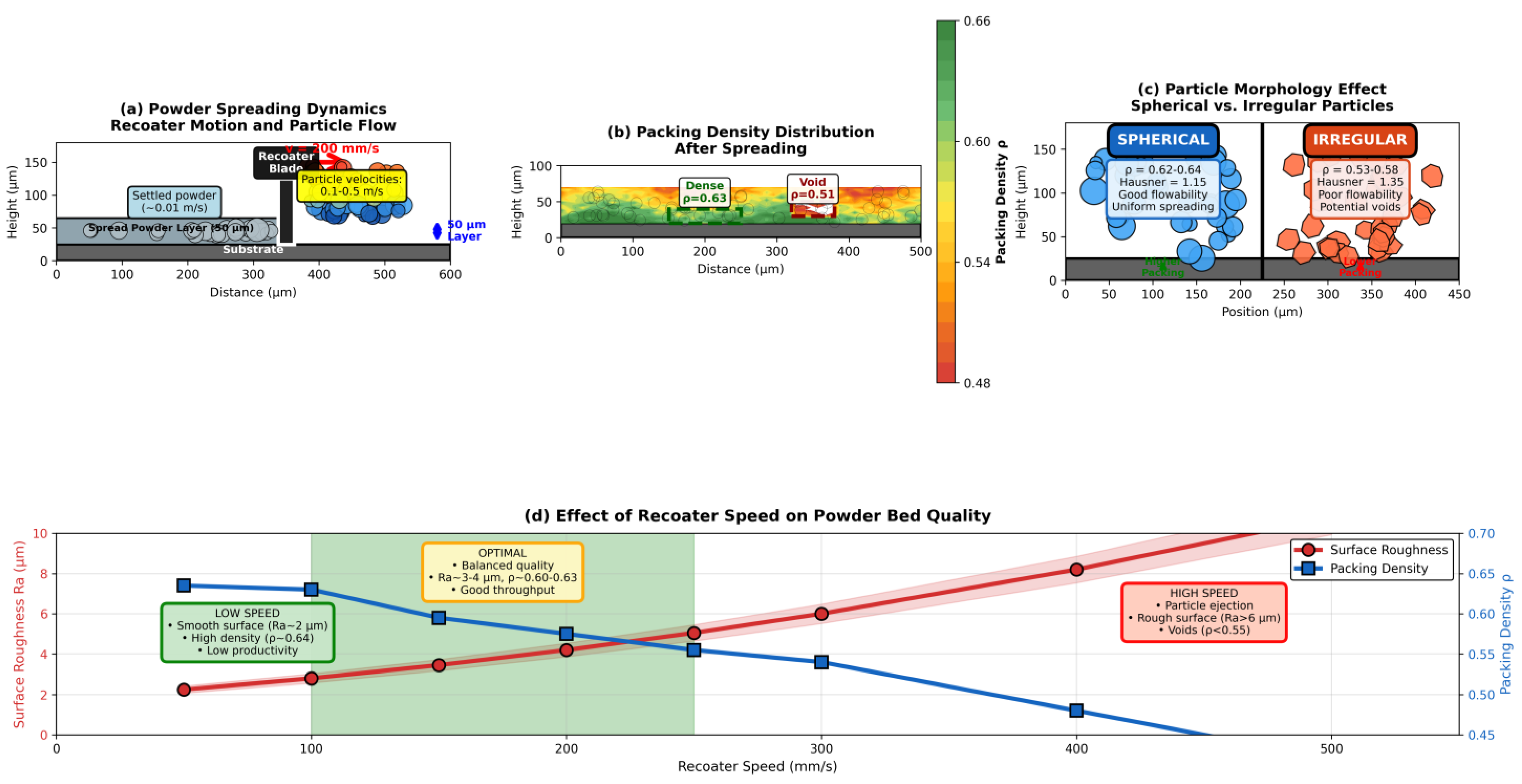

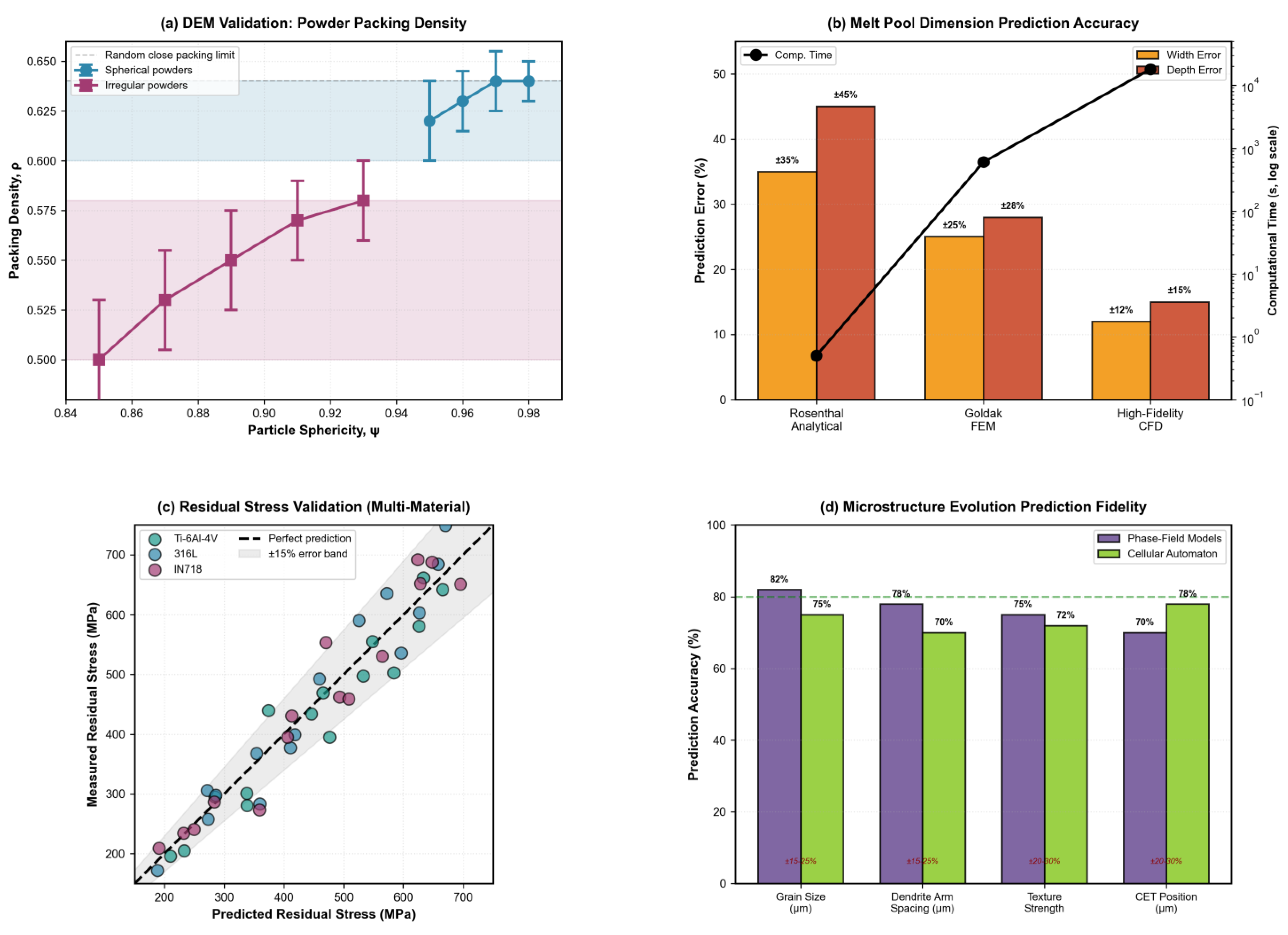

3.1. Powder Spreading and Packing Dynamics

3.1.1. Spreading Strategy Comparisons

3.1.2. Environmental Effects: Gravity and Temperature

3.1.3. Non-Spherical Particles and Recoater Effects

3.1.4. Packing Density Metrics and Dependencies

3.1.5. DEM Fundamentals

3.2. Laser–Powder Interaction and Energy Absorption

3.3. Melt Pool Formation and Dynamics

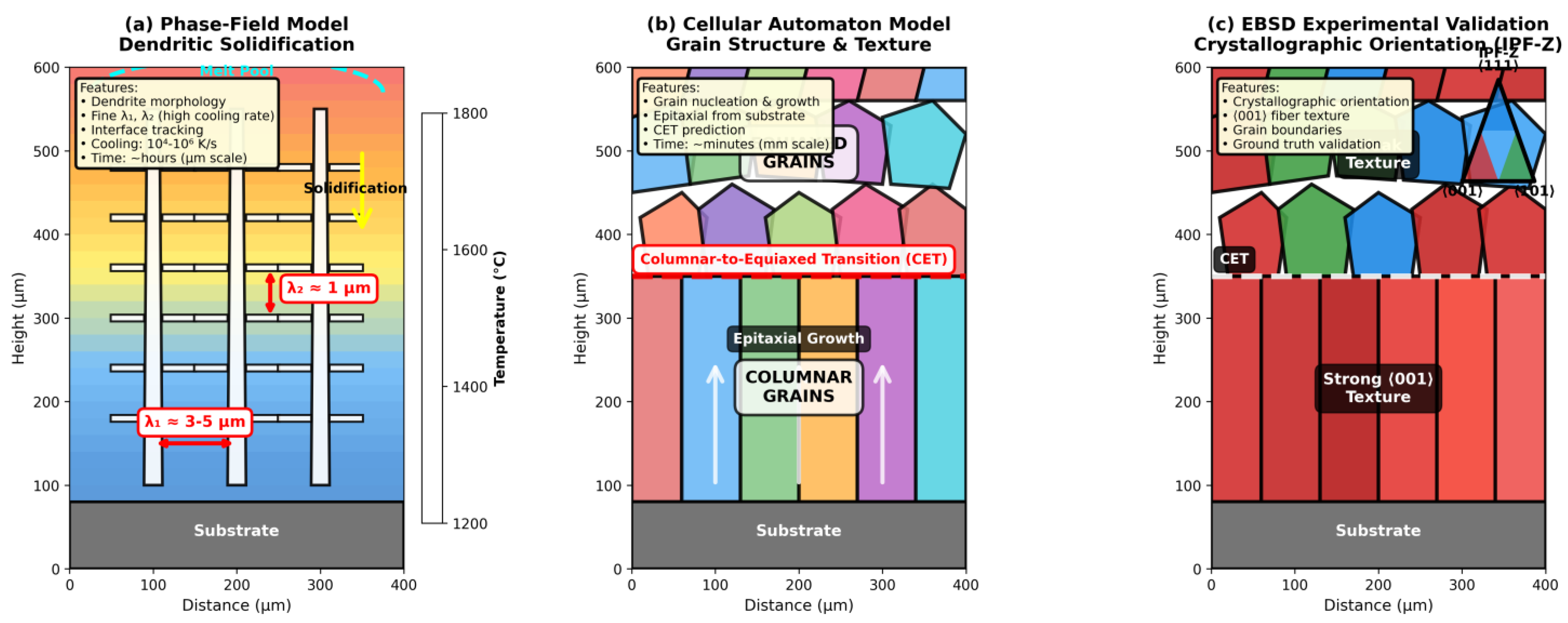

3.4. Solidification and Microstructure Evolution

3.5. Thermomechanical Response and Residual Stress

3.5.1. Influence of Preheating on Residual Stress

3.5.2. Role of Absorptivity Variation

3.5.3. Combined Process Parameter Interactions

3.5.4. Laser Operation Mode Effects

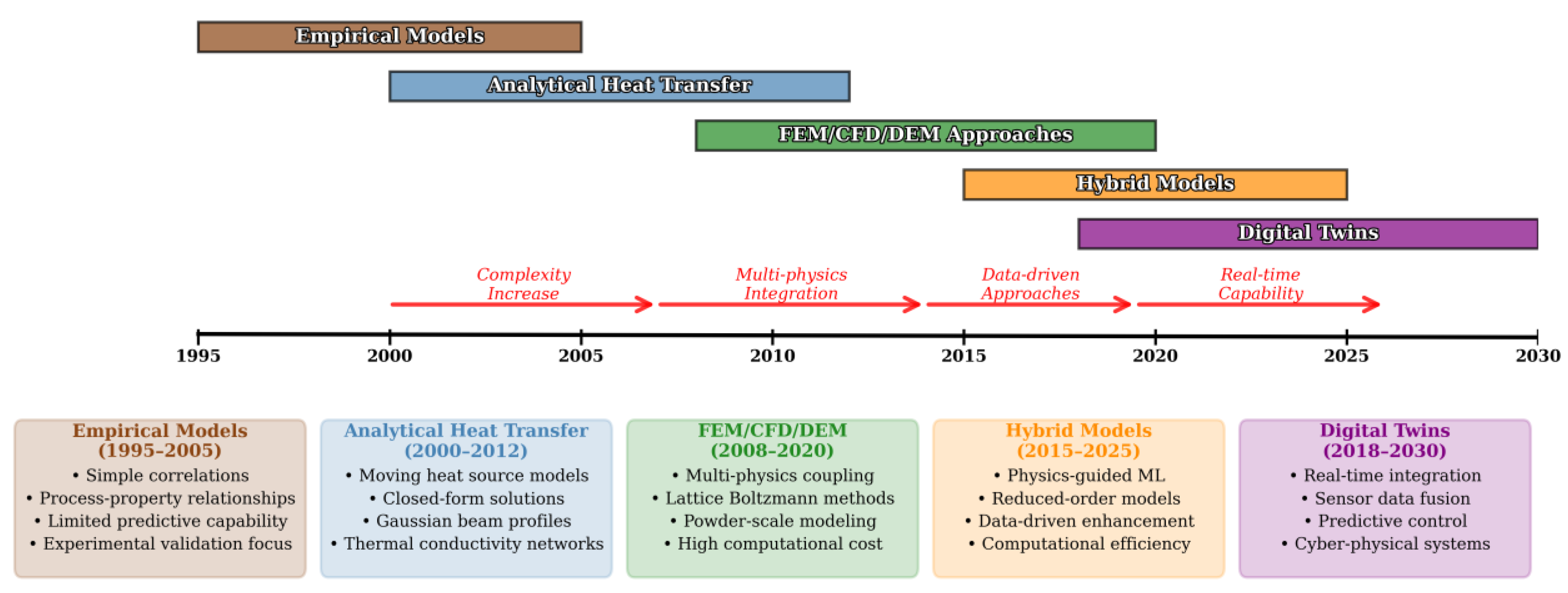

4. Evolution of Modeling Approaches

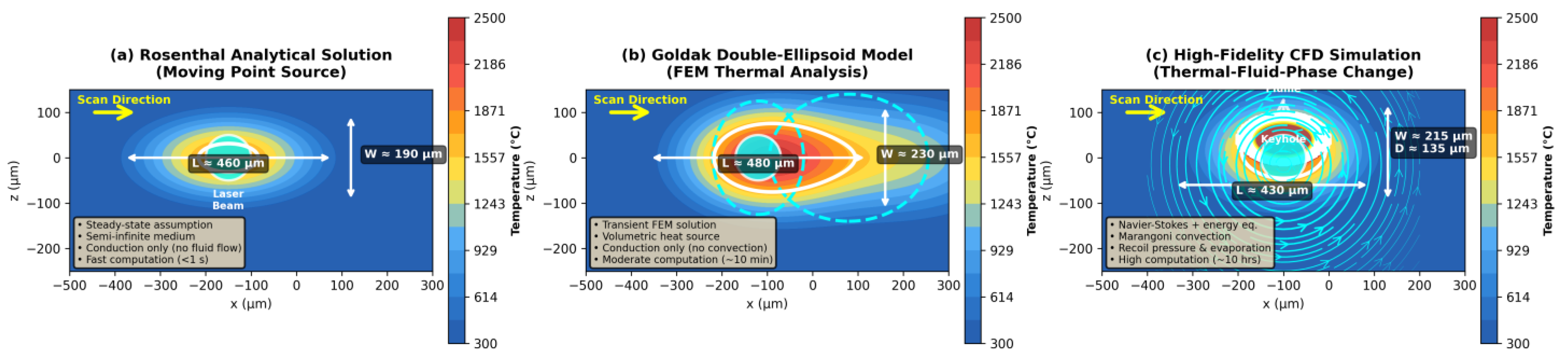

4.1. Physics-Based Modeling

4.2. Hybrid Physics–Data-Driven Approaches

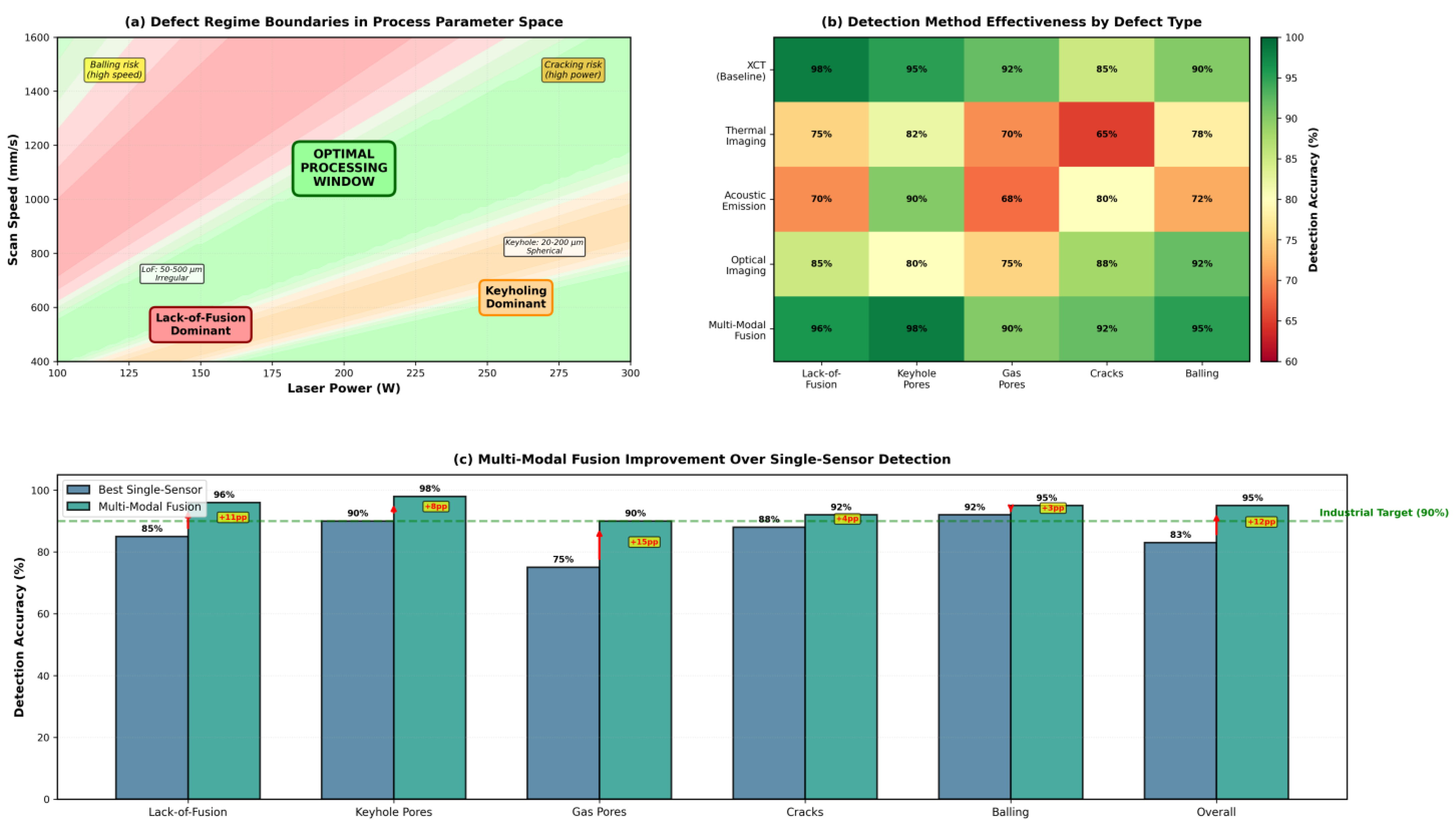

4.3. Integration of In Situ Monitoring Data

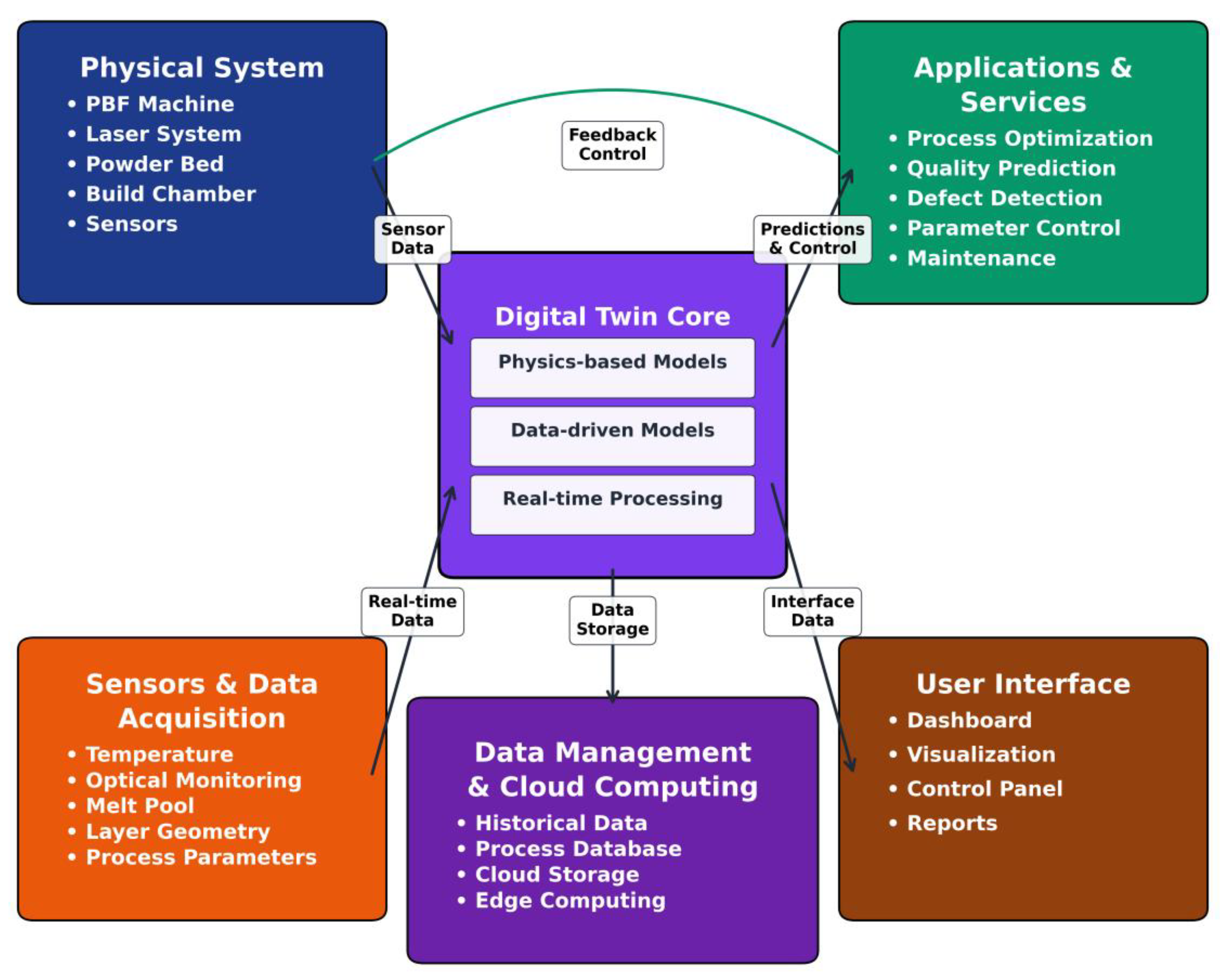

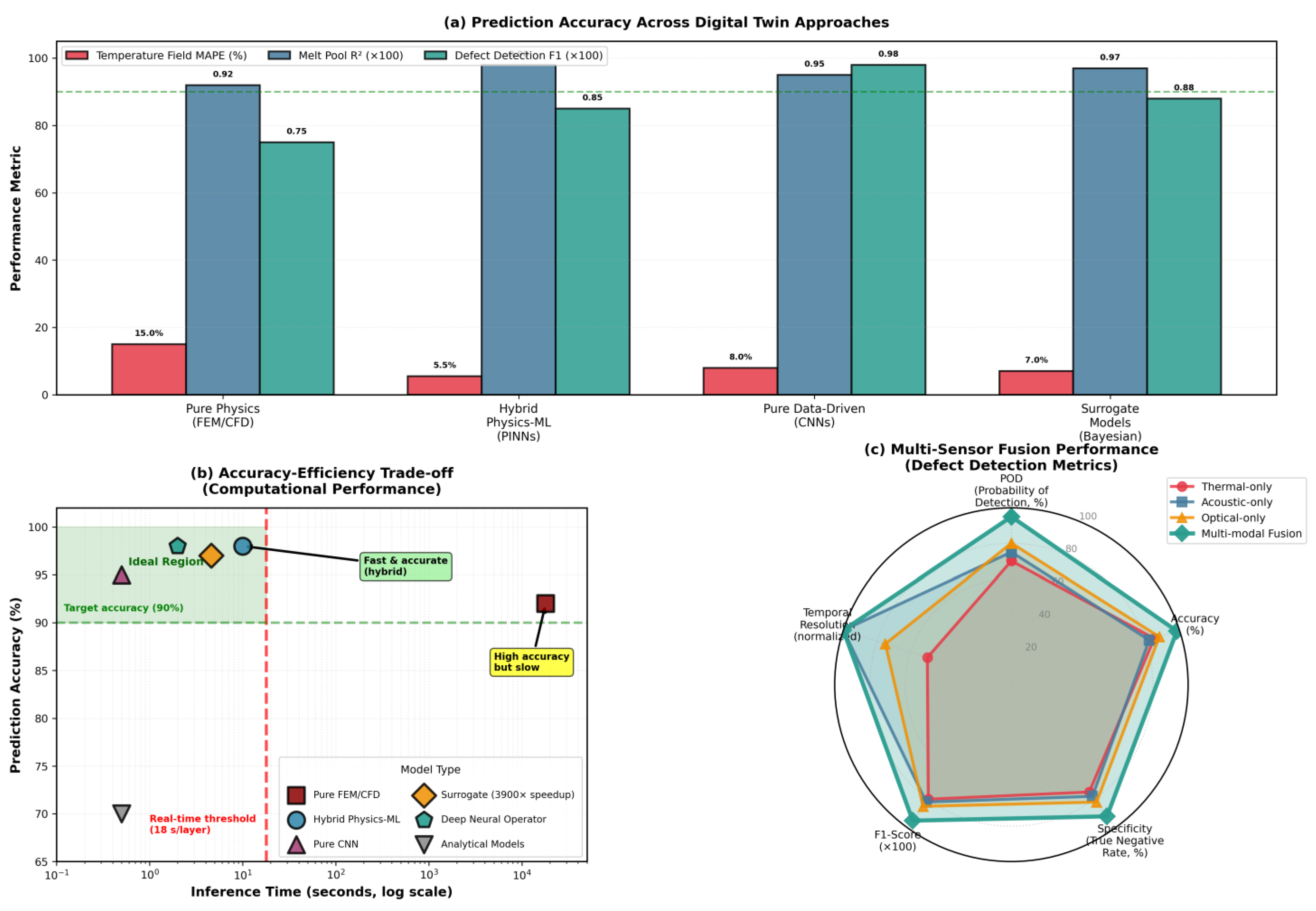

5. Digital Twins and AI Integration for PBF

5.1. Digital Twin Concept and Architecture

5.2. Data Sources and Sensor Integration

5.3. AI and Machine Learning Methods

5.3.1. Supervised Learning for Defect Detection

5.3.2. Self-Supervised and Semi-Supervised Learning

5.3.3. Reinforcement Learning and Model Predictive Control

5.3.4. Physics-Informed Neural Networks

5.3.5. Integration with Digital Twin Frameworks

5.3.6. Validation and Scalability Considerations

5.4. Case Studies of PBF Digital Twin Implementation

6. Optimization Strategies in PBF Manufacturing

6.1. Topology Optimization with PBF Process Constraints

6.2. Machine Learning-Driven Process Parameter Optimization for PBF

6.3. Quality Assurance in PBF via Predictive Models

7. Software Platforms and Tools for PBF Modeling

7.1. Commercial (e.g., ANSYS, Simufact) and Open-Source Tools

7.2. Machine Learning Frameworks for PBF

7.3. Data Management and Visualization Tools

7.4. Integrated Platforms and Digital Twin Solutions

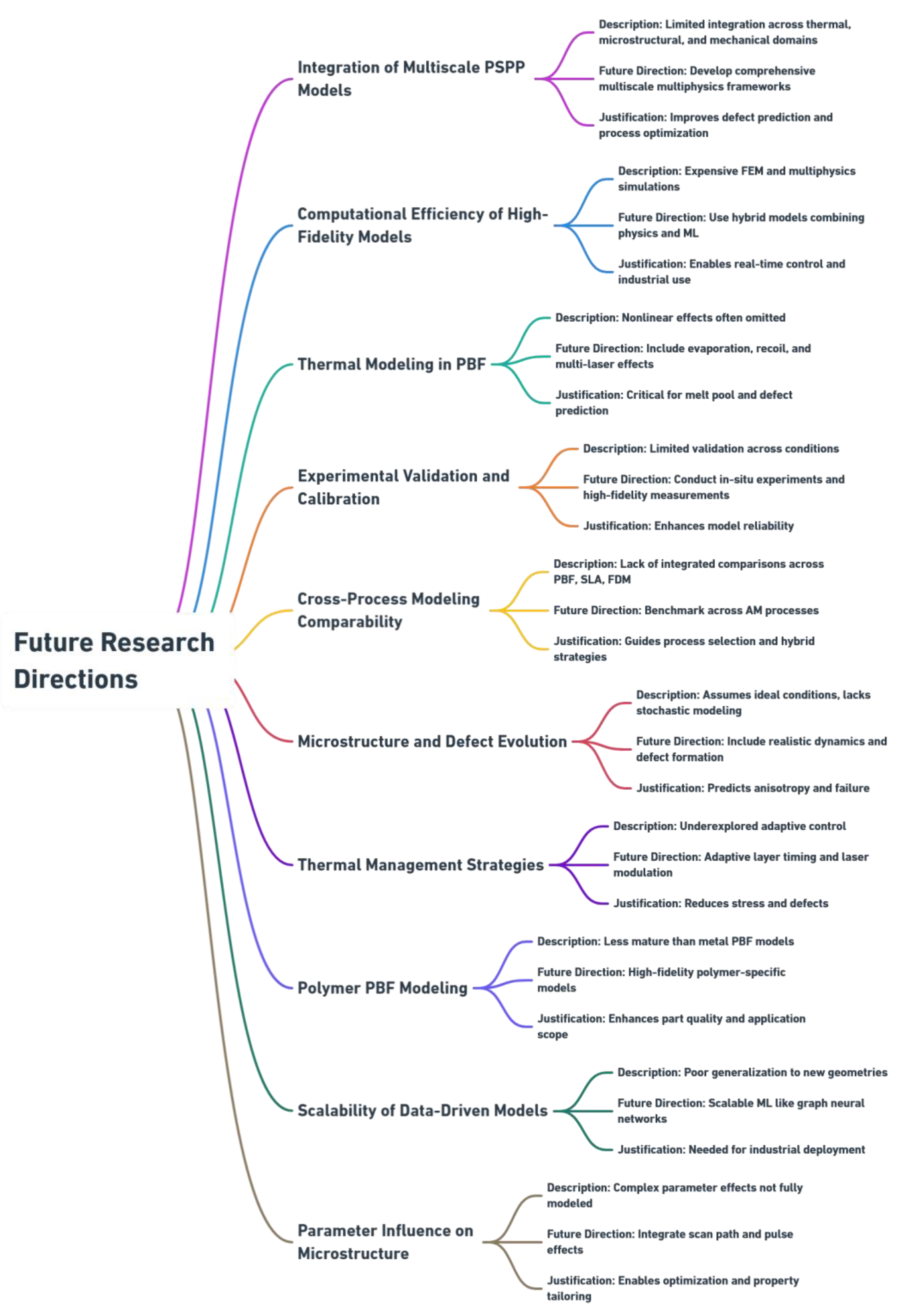

8. Current Challenges and Future Directions in PBF Modeling

9. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-Dimensional |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| AR | Augmented Reality |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| CA | Cellular Automaton |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| CET | Columnar-to-Equiaxed Transition |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| CPFE | Crystal Plastivity Finite Element |

| CT | Computed Tomography |

| CW | Continuous Wave |

| DEM | Discrete Element Method |

| DfAM | Design for Additive Manufacturing |

| DMLS | Direct Metal Laser Sintering |

| DOE | Design of Experiments |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| EBSD | Electron Backscatter Diffraction |

| EBM | Electron Beam Melting |

| ERP | Enterprise Resource Planning |

| FAIR | Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable |

| FCC | Face-Centered Cubic |

| FDM | Fused Deposition Modeling |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| FGM | Functionally Graded Material |

| FVM | Finite Volume Method |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| HCP | Hexagonal Close-Packed |

| HEA | High-Entropy Alloy |

| ICME | Integrated Computational Materials Engineering |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IPF | Inverse Pole Figure |

| IR | Infrared |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LBM | Lattice Boltzmann Method |

| LPBF | Laser–Powder Bed Fusion |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| LWIR | Long-Wave Infrared |

| MAPE | Mean Absolute Percentage Error |

| MES | Manufacturing Execution System |

| MJF | Multi Jet Fusion |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| NDE | Non-Destructive Evaluation |

| NIR | Near-Infrared |

| OPC-UA | Open Platform Communications - Unified Architecture |

| PBF | Powder Bed Fusion |

| PDE | Partial Differential Equation |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative |

| PINN | Physics-Informed Neural Network |

| PLM | Product Lifecycle Management |

| POD | Proper Orthogonal Decomposition/Probability of Detection |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PSP | Process–Structure–Property |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| RSM | Response Surface Methodology |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| SLA | Stereolithography |

| SLM | Selective Laser Melting |

| SLS | Selective Laser Sintering |

| SPH | Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SWIR | Short-Wave Infrared |

| TES | Temperature–Emissivity Separation |

| TO | Topology Optimization |

| TRL | Technology Readiness Level |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

| XCT | X-ray Computed Tomography |

References

- Soundararajan, B.; Sofia, D.; Barletta, D.; Poletto, M. Review on modeling techniques for powder bed fusion processes based on physical principles. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47, 102336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, D.; Kapil, A.; Sharma, A. Advances in computational modeling for laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing: A comprehensive review of finite element techniques and strategies. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 85, 104157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attariani, H.; Petitjean, S.R.; Dousti, M. A digital twin of synchronized circular laser array for powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 123, 1433–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaei, A.; Zhao, C.; He, Y.; Reza Ghiaasiaan, S.; Shi, B.; Shao, S.; Shamsaei, N.; Wu, Z.; Kouraytem, N.; Sun, T.; et al. Defects and anomalies in powder bed fusion metal additive manufacturing. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2022, 26, 100974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mojumder, S.; Lu, Y.; Al Amin, A.; Guo, J.; Xie, X.; Chen, W.; Wagner, G.J.; Cao, J.; Liu, W.K. Statistical parameterized physics-based machine learning digital shadow models for laser powder bed fusion process. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 87, 104214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, H.; Kim, F.; Donmez, A. Application of Digital Twins to Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing Process Control. In Proceedings of the ASME 2023 18th International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference, MSEC 2023, New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 12–16 June 2023; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, A.W.; Mahmood, M.A.; Liou, F. Digital twin–driven optimization of laser powder bed fusion processes: A focus on lack-of-fusion defects. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2024, 30, 1977–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, M.; Dong, W.; Thorborg, J.; To, A.C.; Hattel, J.H. A review of multi-scale and multi-physics simulations of metal additive manufacturing processes with focus on modeling strategies. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47, 102278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinovieva, O.; Romanova, V.; Dymnich, E.; Zinoviev, A.; Balokhonov, R. A Review of Computational Approaches to the Microstructure-Informed Mechanical Modelling of Metals Produced by Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2023, 16, 6459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Yadaiah, N.; Prakash, C.; Ramakrishna, S.; Dixit, S.; Gupta, L.R.; Buddhi, D. Laser powder bed fusion: A state-of-the-art review of the technology, materials, properties & defects, and numerical modelling. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 2109–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.M.; Liu, Y.; Raman, S.; Siddique, Z. Digital Twins in Additive Manufacturing: A Systematic Review. Internet Things 2024, 33, 101692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Amor, S.; Elloumi, N.; Eltaief, A.; Louhichi, B.; Alrasheedi, N.H.; Seibi, A. Digital Twin Implementation in Additive Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Review. Processes 2024, 12, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crump, S.S. Apparatus and Method for Creating Three-Dimensional Objects. U.S. Patent 5,121,329, 30 October 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Anderson, T.; Chou, K. Review on powder-based electron beam additive manufacturing technology. Manuf. Rev. 2014, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruth, J.P.; Levy, G.; Klocke, F.; Childs, T.H.C. Consolidation phenomena in laser and powder-bed based layered manufacturing. CIRP Ann. 2007, 56, 730–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruth, J.P.; Mercelis, P.; Van Vaerenbergh, J.; Froyen, L.; Rombouts, M. Binding mechanisms in selective laser sintering and selective laser melting. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2005, 11, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, C.Y.; Chua, C.K.; Dong, Z.L.; Liu, Z.H.; Zhang, D.Q.; Loh, L.E.; Sing, S.L. Review of selective laser melting: Materials and applications. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2015, 2, 041101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Zou, Y.; Lim, C.V.S.; Wu, X. Review of laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) fabricated Ti-6Al-4V: Process, post-process treatment, microstructure, and property. Light Adv. Manuf. 2021, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martucci, A.; Aversa, A.; Lombardi, M. Ongoing Challenges of Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion Processing of Al Alloys and Potential Solutions from the Literature—A Review. Materials 2023, 16, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olakanmi, E.O.; Cochrane, R.F.; Dalgarno, K.W. A review on selective laser sintering/melting (SLS/SLM) of aluminium alloy powders: Processing, microstructure, and properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2015, 74, 401–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulkhair, N.T.; Simonelli, M.; Parry, L.; Ashcroft, I.; Tuck, C.; Hague, R. 3D printing of Aluminium alloys: Additive Manufacturing of Aluminium alloys using selective laser melting. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2019, 106, 100578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Kong, D.; Li, R.; He, X.; Dong, C. Corrosion of Duplex Stainless Steel Manufactured by Laser Powder Bed Fusion: A Critical Review. Acta Metall. Sin. Engl. Lett. 2024, 37, 587–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoura, A.; Omidi, N.; Barka, N.; Karganroudi, S.S.; Dehghan, S. Selective Laser Melting of Stainless Steels: A review of Process, Microstructure and Properties. Met. Mater. Int. 2024, 30, 2343–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimharaju, S.R.; Zeng, W.; See, T.L.; Zhu, Z.; Scott, P.; Jiang, X.; Lou, S. A comprehensive review on laser powder bed fusion of steels: Processing, microstructure, defects and control methods, mechanical properties, current challenges and future trends. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 75, 375–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghdadi, N.; Laleh, M.; Moyle, M.; Primig, S. Additive manufacturing of steels: A review of achievements and challenges. J. Mater. Sci. 2021, 56, 64–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, B.; An, K.; Wang, Y.; Liu, D.; Lu, W.; Zhu, L.; Liu, C. Recent advance in laser powder bed fusion of Ti–6Al–4V alloys: Microstructure, mechanical properties and machinability. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2025, 20, e2446952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytro, S.; Szymon, B.; Michal, K. An extended laser beam heating model for a numerical platform to simulate multi-material selective laser melting. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 128, 3451–3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aufa, A.N.; Hassan, M.Z.; Ismail, Z. Recent advances in Ti-6Al-4V additively manufactured by selective laser melting for biomedical implants: Prospect development. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 896, 163072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Canyurt, O.E.; Sezer, H.K. A systematic review of Inconel 939 alloy parts development via additive manufacturing process. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafaei, A.; Ghiaasiaan, R.; Ho, I.T.; Strayer, S.; Chang, K.C.; Shamsaei, N.; Shao, S.; Paul, S.; Yeh, A.C.; Tin, S.; et al. Additive manufacturing of nickel-based superalloys: A state-of-the-art review on process-structure-defect-property relationship. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2023, 136, 101108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, S.; Smith, P.; Xu, Z.; Gaspard, G.; Hyde, C.J.; Wits, W.W.; Ashcroft, I.A.; Chen, H.; Clare, A.T. Powder Bed Fusion of nickel-based superalloys: A review. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2021, 165, 103729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wang, D.; Liu, W.; Fang, X.; Wellmann, D.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, Y. A Review on Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Inconel 625 Nickel-Based Alloy. Appl. Sci. 2019, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svyetlichnyy, D. Model of the Selective Laser Melting Process-Powder Deposition Models in Multistage Multi-Material Simulations. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrpouya, M.; Tuma, D.; Vaneker, T.; Afrasiabi, M.; Bambach, M.; Gibson, I. Multimaterial powder bed fusion techniques. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2022, 28, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneck, M.; Horn, M.; Schmitt, M.; Seidel, C.; Schlick, G.; Reinhart, G. Review on additive hybrid- and multi-material-manufacturing of metals by powder bed fusion: State of technology and development potential. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 6, 881–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Liu, S.; Singh, R.K.; Sharma, A.K.; Rawat, P. A state-of-art review on functionally graded materials (FGMs) manufactured by 3D printing techniques: Advantages, existing challenges, and future scope. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 131, 2051–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Feng, Z.; Hao, L.; Huang, L.; Xin, C.; Wang, Y.; Bilotti, E.; Essa, K.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; et al. A Review on Functionally Graded Materials and Structures via Additive Manufacturing: From Multi-Scale Design to Versatile Functional Properties. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2020, 5, 1900981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svyetlichnyy, D. Lattice Boltzmann Modeling of Additive Manufacturing of Functionally Graded Materials. Entropy 2024, 27, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. Progress in Additive Manufacturing of High-Entropy Alloys. Materials 2024, 17, 5917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhao, S.; Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, L.; Li, Y. Influence of Processing Parameters on Additively Manufactured Architected Cellular Metals: Emphasis on Biomedical Applications. J. Funct. Biomater. 2025, 16, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svyetlichnyy, D. Simulation of the selective laser sintering/melting process of bioactive glass 45S5. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2024, 136, 103009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, R.; Lopes, S.I.; Prashanth, K.G. Selective Laser Melting and Spark Plasma Sintering: A Perspective on Functional Biomaterials. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maharma, A.Y.; Patil, S.P.; Markert, B. Effects of porosity on the mechanical properties of additively manufactured components: A critical review. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 122001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, A.; Yadroitsava, I.; Yadroitsev, I. Effects of defects on mechanical properties in metal additive manufacturing: A review focusing on X-ray tomography insights. Mater. Des. 2020, 187, 108385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.N.; Deoghare, A.B. Laser Shock Peening of Laser Based Directed Energy Deposition and Powder Bed Fusion Additively Manufactured Parts: A Review. Met. Mater. Int. 2022, 29, 1563–1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.L.; Li, X. An overview of residual stresses in metal powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 27, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekipour, E.; El-Mounayri, H. Common defects and contributing parameters in powder bed fusion AM process and their classification for online monitoring and control: A review. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 951, 527–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.J.; Bitharas, I.; Perkins, K.G.; Moore, A.J. Volumetric heat source calibration for laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 60, 103267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastac, L. A 3D Multiscale Model for Prediction of the Microstructure Evolution in Ti6Al4V Components Produced by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 1281, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakizadi, A.; Mallipeddi, D.; Dadbakhsh, S.; M’Saoubi, R.; Krajnik, P. Post-processing of additively manufactured metallic alloys—A review. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2022, 179, 103908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepylo, N.; Huang, X.; Patnaik, P.C. Laser-Based Additive Manufacturing Technologies for Aerospace Applications. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019, 21, 1900617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, D.; Singh, S.P.; Behera, B.K. A review on recent advancements in additive manufacturing techniques. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part E J. Process Mech. Eng. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Avinashi, S.K.; Rao, J.; Gautam, C. Recent Advances in Additive Manufacturing, Applications and Challenges for Dentistry: A Review. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 3987–4019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M. Additive Manufacturing Processes in Medical Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alinejadian, N.; Kollo, L.; Odnevall, I. Progress in additive manufacturing of MoS2-based structures for energy storage applications—A review. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 139, 106331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, D.; Ananth, K. Recent Advances in Alloy Development for Metal Additive Manufacturing in Gas Turbine/Aerospace Applications: A Review. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 2022, 102, 311–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorussen, B.J.A.; Geers, M.G.D.; Remmers, J.J.C. A discrete element framework for the numerical analysis of particle bed-based additive manufacturing processes. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 4753–4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girnth, S.; Heitkamp, T.; Wacker, C.; Waldt, N.; Klawitter, G.; Dröder, K. Dimensionless quantities in discrete element method: Powder model parameterization for additive manufacturing. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 9, 1967–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, Y.; Yuan, W.; Pang, S.; Yan, W.; Shi, Y. A Review on Discrete Element Method Simulation in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. Chinese J. Mech. Eng. Addit. Manuf. Front. 2022, 1, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, S.; Cleary, P.W.; Delaney, G.; Phua, A.; Sinnott, M.; Gunasegaram, D.; Davies, C. A Coupled DEM/SPH Computational Model to Simulate Microstructure Evolution in Ti-6Al-4V Laser Powder Bed Fusion Processes. Metals 2021, 11, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarab, M.; Dorussen, B.J.A.; Poelsma, S.S.; Remmers, J.J.C. Development of optimal L-PBF process parameters using an accelerated discrete element simulation framework. Granul. Matter 2024, 26, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, R.W.; Oropeza, D.; Praegla, P.M.; Weissbach, R.; Meier, C.; Wall, W.A.; John Hart, A. Quantitative analysis of thin metal powder layers via transmission X-ray imaging and discrete element simulation: Blade-based spreading approaches. Powder Technol. 2024, 432, 119106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, Y.M.; Bayly, A.E. A DEM study of powder spreading in additive layer manufacturing. Granul. Matter 2020, 22, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, D.; An, X.; Fu, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Zou, Q.; Dong, K. Dynamic investigation on the powder spreading during selective laser melting additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, M.A.; Tullis, S.; Elbestawi, M. Accelerating Laser Powder Bed Fusion: The Influence of Roller-Spreading Speed on Powder Spreading Performance. Metals 2024, 14, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissbach, R.; Praegla, P.M.; Wall, W.A.; Hart, A.J.; Meier, C. Exploration of improved, roller-based spreading strategies for cohesive powders in additive manufacturing via coupled DEM-FEM simulations. Powder Technol. 2024, 443, 119956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Tan, Y.; Bao, T.; Xu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Jiang, S. Discrete Element Simulation of the Effect of Roller-Spreading Parameters on Powder-Bed Density in Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2020, 13, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Namilae, S. Parametric Analysis and Designing Maps for Powder Spreading in Metal Additive Manufacturing. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 142, 2067–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neveu, A.; Francqui, F.; Lumay, G.; Jenkins, B.; Valadian, R. Spreadability of Metal Powders: Combining Powder Characterization And DEM Simulations. In Proceedings of the Euro Powder Metallurgy 2025 Congress & Exhibition, Glasgow, UK, 14–17 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zinatlou Ajabshir, S.; Hare, C.; Sofia, D.; Barletta, D.; Poletto, M. Investigating the effect of temperature on powder spreading behaviour in powder bed fusion additive manufacturing process by Discrete Element Method. Powder Technol. 2024, 436, 119468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Shaheen, M.Y.; Pöschel, T. Effect of cohesion on structure of powder layers in additive manufacturing. Granul. Matter 2023, 25, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Chen, D.; Yang, H.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, T.; Chen, D.; Yang, H.; Zhao, W.; et al. Spreading Behavior of Non-Spherical Particles with Reconstructed Shapes Using Discrete Element Method in Additive Manufacturing. Polymers 2024, 16, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Hassanpour, A.; Bayly, A.E. Linking particle properties to layer characteristics: Discrete element modelling of cohesive fine powder spreading in additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, S.; Bian, H.; Aoyagi, K.; Yamanaka, K.; Chiba, A. Spreading behavior of Ti48Al2Cr2Nb powders in powder bed fusion additive manufacturing process: Experimental and discrete element method study. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 49, 102489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Pöschel, T. Shape effects in binary mixtures of PA12 powder in additive manufacturing. Powder Technol. 2024, 448, 120326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.M.; Zhao, J.B.; Zhao, Y.H.; Wang, Z.G. Discrete element analysis for effects of recoating blade and surface morphology of substrate on powder spreading quality. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2454, 012016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habiba, U.; Hebert, R.J. Powder Spreading Mechanism in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing: Experiments and Computational Approach Using Discrete Element Method. Materials 2023, 16, 2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penny, R.W.; Praegla, P.M.; Ochsenius, M.; Oropeza, D.; Weissbach, R.; Meier, C.; Wall, W.A.; Hart, A.J. Spatial mapping of powder layer density for metal additive manufacturing via transmission X-ray imaging. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Q.; Shi, Y.; Yan, W. Packing quality of powder layer during counter-rolling-type powder spreading process in additive manufacturing. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2020, 153, 103553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrampos, P.; Vosniakos, G.C. A Study on Powder Spreading Quality in Powder Bed Fusion Processes Using Discrete Element Method Simulation. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, P.S.; Phua, A.; Davies, C.H.J.; Delaney, G.W. Modelling the influences of powder layer depth and particle morphology on powder bed fusion using a coupled DEM-CFD approach. Powder Technol. 2023, 429, 118927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Nan, W. Analysis of the metrics and mechanism of powder spreadability in powder-based additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 71, 103596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, M.; Roux, G.; Burr, A.; Ablitzer, C.; Garandet, J.P. Identification of the influential DEM contact law parameters on powder bed quality and flow in additive manufacturing configurations. Powder Technol. 2023, 429, 118937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierwisch, C.; Dietemann, B.; Najuch, T. Particle-based modelling of laser powder bed fusion of metals with emphasis on the melting mode transition. Granul. Matter 2024, 26, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Garcia, D.; Kamath, R.R.; Dou, C.; Ma, X.; Shen, B.; Choo, H.; Fezzaa, K.; Yu, H.Z.; Kong, Z. In situ melt pool measurements for laser powder bed fusion using multi sensing and correlation analysis. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 13716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Gao, L.; Clark, S.J.; Fezzaa, K.; Shevchenko, P.; Choi, A.; Everhart, W.; Rollett, A.D.; Chen, L.; Sun, T. Machine learning-aided real-time detection of keyhole pore generation in laser powder bed fusion. Science 2023, 379, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, S.; Rengasamy, D.; Hyde, C.J.; Figueredo, G.P.; Rothwell, B. Machine learning to determine the main factors affecting creep rates in laser powder bed fusion. J. Intell. Manuf. 2021, 32, 2353–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Li, B. An integrated computation framework for predicting mechanical performance of single-phase alloys manufactured using laser powder bed fusion: A case study of CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 109180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, T.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Xuan, F. Integrated computational materials engineering (ICME) for predicting tensile properties of additively manufactured defect-free single-phase high-entropy alloy. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2025, 20, e2441947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weirather, J.; Rozov, V.; Wille, M.; Schuler, P.; Seidel, C.; Adams, N.A.; Zaeh, M.F. A Smoothed Particle Hydrodynamics Model for Laser Beam Melting of Ni-based Alloy 718. Comput. Math. Appl. 2019, 78, 2377–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, S.L.; Praegla, P.M.; Cyron, C.J.; Wall, W.A.; Meier, C. A versatile SPH modeling framework for coupled microfluid-powder dynamics in additive manufacturing: Binder jetting, material jetting, directed energy deposition and powder bed fusion. Eng. Comput. 2022, 38, 4853–4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baehr, S.; Fritz, F.; Adami, S.; Ammann, T.; Adams, N.A.; Zaeh, M.F. Investigations on the Heat Balance of the Melt Pool during PBF-LB/M under Various Process Gases. Metals 2024, 14, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D. Tailoring thermodynamics, fluid flow, and surface quality of laser powder bed fusion metallic powder through mass and momentum transfer modeling and monitoring. In Laser Additive Manufacturing of Metallic Materials and Components; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 429–482. ISBN 978-0-12-823783-0. [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt, C.; Steinmann, P.; Mergheim, J. Thermo-mechanical simulations of powder bed fusion processes: Accuracy and efficiency. Adv. Model. Simul. Eng. Sci. 2022, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabh, C.K.P.; Zhao, X. Single-camera Two-Wavelength Imaging Pyrometry for Melt Pool Temperature Measurement and Monitoring in Laser Powder Bed Fusion based Additive Manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 79, 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint, T.F.; Robson, J.D.; Esmati, P.; Grilli, N.; Parivendhan, G.; Cardiff, P. Version 2.0—LaserbeamFoam: Laser ray-tracing and thermally induced state transition simulation toolkit. SoftwareX 2024, 25, 101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusarov, A.V. Radiative transfer, absorption, and reflection by metal powder beds in laser powder-bed processing. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 2020, 257, 107366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D. Laser energy absorption and distribution behaviors of randomly packed powder bed using ray tracing method during laser powder bed fusion of metallic materials. In Laser Additive Manufacturing of Metallic Materials and Components; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 307–345. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Huang, M.; Ma, Y.H.; Qin, M.L.; Liu, T.T. Simulation of Powder Packing and Thermo-Fluid Dynamic of 316L Stainless Steel by Selective Laser Melting. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2020, 29, 7369–7381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katagiri, J.; Nomoto, S.; Kusano, M.; Watanabe, M. Particle Size Effect on Powder Packing Properties and Molten Pool Dimensions in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Simulation. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2024, 8, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Chen, H.; Peng, C.; Lupoi, R.; Yin, S. Revealing melt-vapor-powder interaction towards laser powder bed fusion process via DEM-CFD coupled model. Surf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Garg, R.K.; Sharma, V.S.; Alba-Baena, N.G.; Sachdeva, A.; Chand, R.; Singh, S. Multi-physics continuum modelling approaches for metal powder additive manufacturing: A review. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2020, 26, 737–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Naceur, H.; Saadlaoui, Y.; Dubar, L.; Bergheau, J.M. A comprehensive comparison of modeling strategies and simulation techniques applied in powder-based metallic additive manufacturing processes. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 110, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayi, Y.A.; Dal, M.; Peyre, P.; Bellet, M.; Metton, C.; Moriconi, C.; Fabbro, R. Transient dynamics and stability of keyhole at threshold in laser powder bed fusion regime investigated by finite element modeling. J. Laser Appl. 2021, 33, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Spear, A. Multiphysics Modeling Framework to Predict Process-Microstructure-Property Relationship in Fusion-Based Metal Additive Manufacturing. Acc. Mater. Res. 2024, 5, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabi, M.; Bambach, M. Modelling and simulation of metal additive manufacturing processes with particle methods: A review. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2023, 18, e2274494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korneev, B.; Zakirov, A.; Bogdanova, M.; Belousov, S.; Perepelkina, A.; Iskandarova, I.; Potapkin, B. A numerical study of powder wetting influence on the morphology of laser powder bed fusion manufactured thin walls. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 74, 103705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zöller, C.; Adams, N.A.; Adami, S. Beam-shaping in laser-based powder bed fusion of metals: A computational analysis of point-ring intensity profiles. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 93, 104402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, H.; Fu, Y.; Wei, C.; Li, L.; Qian, L.; Zhou, W.; Li, Y.; Ren, X. The impact of thermocapillary on equiaxed/columnar microstructure evolution in laser powder bed fusion: A high-fidelity ray-tracing based finite volume and cellular automaton study. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2024, 326, 118335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Pan, J.; Gu, Y.; Hu, X.; Duan, Z.; Li, H. Effect of molten pool flow and recoil pressure on grain growth structures during laser powder bed fusion by an integrated model. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 223, 125219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R.; Ahluwalia, R.; Hock, G.T.W.; Ying, C.S.; Sun, C.N.; Wang, P.; Cheh, D.T.C.; Sharon, N.M.L.; Vastola, G.; Zhang, Y.W. Concurrent modeling of porosity and microstructure in multilayer three-dimensional simulations of powder-bed fusion additive manufacturing of INCONEL 718. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 60, 103266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Joshi, S.S.; Pantawane, M.V.; Radhakrishnan, M.; Mazumder, S.; Dahotre, N.B. Multiphysics multi-scale computational framework for linking process–structure–property relationships in metal additive manufacturing: A critical review. Int. Mater. Rev. 2023, 68, 943–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Zhu, Q.; Zhao, Z. Computational thermal multi-phase flow for metal additive manufacturing. In Modeling and Simulation in Science, Engineering and Technology; Birkhäuser: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 533–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, C.; Penny, R.W.; Zou, Y.; Gibbs, J.S.; Hart, A.J. Thermophysical phenomena in metal additive manufacturing by selective laser melting: Fundamentals, modeling, simulation, and experimentation. Annu. Rev. Heat Transf. 2017, 20, 241–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L. Understanding melt pool characteristics in laser powder bed fusion: An overview of single- and multi-track melt pools for process optimization. Adv. Powder Mater. 2023, 2, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Pan, Z.; Gao, M.; Han, L.; Choi, J.-P.; Zhang, H. Multi-Physics Modeling of Melting-Solidification Characteristics in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process of 316L Stainless Steel. Materials 2024, 17, 946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, K.; He, X.; Kong, D.; Dong, C. Multi-physical field simulation to yield defect-free IN718 alloy fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Lett. 2024, 355, 135437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promoppatum, P.; Yao, S.-C. Analytical evaluation of defect generation for selective laser melting of metals. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 103, 1185–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A.K.; Rankouhi, B.; Thoma, D.J. Predictive process mapping for laser powder bed fusion: A review of existing analytical solutions. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2022, 26, 101024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ökten, K.; Örnek, B.N.; Biyikoğlu, A. Development of an analytical model to investigate temperature distribution and melt geometry in the laser powder bed fusion process under different operating parameters. J. Laser Appl. 2025, 37, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estupinan Donoso, A.A.; Peters, B. Exploring a Multiphysics Resolution Approach for Additive Manufacturing. JOM 2018, 70, 1604–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, Q.; Chen, L.; Yan, W. In-situ experimental and high-fidelity modeling tools to advance understanding of metal additive manufacturing. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2023, 193, 104077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, H.; Zeugner, T.; Zaeh, M.F. Thermographic process monitoring in powderbed based additive manufacturing. AIP Conf. Proc. 2015, 1650, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshiri, M.; Pedersen, D.B.; Tosello, G.; Nadimpalli, V.K. Performance evaluation of in-situ near-infrared melt pool monitoring during laser powder bed fusion. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2023, 18, e2205387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, A.; Ganesh, K.V.; Mahapatra, D.R. Multi-Scale Modeling of Selective Laser Melting Process; SAE Technical Paper; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprio, L.; Demir, A.G.; Previtali, B. Understanding the effects of temporal waveform modulation of the laser emission power in laser powder bed fusion: Part I—Analytical modelling. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2022, 55, 495101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsazadeh, M.; Ebrahimi, H.; Sichani, M.S.; Dahotre, N. A Novel Physics-Based Model for Predicting Melt Pool Dimensions in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2024, 146, 081001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ning, J.; Garmestani, H.; Liang, S.Y. Analytical Prediction of Molten Pool Dimensions in Powder Bed Fusion Considering Process Conditions-Dependent Laser Absorptivity. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queva, A.; Guillemot, G.; Moriconi, C.; Bergeron, R.; Bellet, M. Mesoscale multilayer multitrack modeling of melt pool physics in laser powder bed fusion of lattice metal features. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 93, 104365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D. Mesoscale understanding of particle melting behavior, thermodynamic mechanism, and porosity evolution of randomly packed powder-bed using finite volume method. In Laser Additive Manufacturing of Metallic Materials and Components; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2023; pp. 347–395. [Google Scholar]

- Queva, A.; Guillemot, G.; Moriconi, C.; Metton, C.; Bellet, M. Numerical study of the impact of vaporisation on melt pool dynamics in Laser Powder Bed Fusion—Application to IN718 and Ti–6Al–4V. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 35, 101249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trejos-Taborda, J.; Reyes-Osorio, L.; Garza, C.; del Carmen Zambrano-Robledo, P.; Lopez-Botello, O. Finite element modeling of melt pool dynamics in laser powder bed fusion of 316L stainless steel. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 120, 3947–3961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmoula, M.; Musinski, W. Predicting and correlating melt pool characteristics with processing parameters in IN625 powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 121, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Jiang, W.G.; Qin, Q.H.; Xu, G.G.; Liu, F.C. High-fidelity numerical model of melt pool dynamics in selective multi-laser melting of Inconel 718 under different scanning strategies. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 36, 106913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorasani, M.; Ghasemi, A.H.; Leary, M.; Downing, D.; Gibson, I.; Sharabian, E.G.; Veetil, J.K.; Brandt, M.; Bateman, S.; Rolfe, B. Benchmark models for conduction and keyhole modes in laser-based powder bed fusion of Inconel 718. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 164, 109509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zöller, C.; Adams, N.A.; Adami, S. Numerical investigation of balling defects in laser-based powder bed fusion of metals with Inconel 718. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 73, 103658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzyzanowski, M.; Svyetlichnyy, D. A multiphysics simulation approach to selective laser melting modelling based on cellular automata and lattice Boltzmann methods. Comput. Part. Mech. 2022, 9, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Ding, W.J.; Vastola, G.; Zhang, Y.W. Quantitative study on the dynamics of melt pool and keyhole and their controlling factors in metal laser melting. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 54, 102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouhan, A.; Mädler, L.; Ellendt, N. Modeling of rapid solidification in Laser Powder Bed Fusion processes. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 238, 112918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manav, M.; Perraudin, N.; Lin, Y.; Afrasiabi, M.; Perez-Cruz, F.; Bambach, M.; De Lorenzis, L. MeltpoolINR: Predicting temperature field, melt pool geometry, and their rate of change in laser powder bed fusion. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmasian, A.; Ogoke, F.; Akbari, P.; Malen, J.; Beuth, J.; Farimani, A.B. Surrogate Modeling of Melt Pool Thermal Field using Deep Learning. Addit. Manuf. Lett. 2022, 5, 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, E.D.; Fortney, J.J.; Kalourazi, S.F.; Wang, F.; Zhang, H.; Li, Z.; Greenwood, M.; Phillion, A. A phase field methodology for simulating the microstructure evolution during laser powder bed fusion in-situ alloying process. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 1281, 012017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wang, L.; Yan, W. Phase-field modeling of grain evolutions in additive manufacturing from nucleation, growth, to coarsening. Npj Comput. Mater. 2021, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, S.M.; Tavakoli, R.; Romero, I.; Tourret, D. Grain growth competition during melt pool solidification—Comparing phase-field and cellular automaton models. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2022, 216, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kühn, P.; Yi, M.; Egger, H.; Xu, B.X. Non-isothermal Phase-Field Modeling of Heat–Melt–Microstructure-Coupled Processes During Powder Bed Fusion. JOM 2020, 72, 1719–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Xue, T.; Liao, S.; Cao, J. Accelerating phase-field simulation of three-dimensional microstructure evolution in laser powder bed fusion with composable machine learning predictions. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 79, 103938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peivaste, I.; Siboni, N.H.; Alahyarizadeh, G.; Ghaderi, R.; Svendsen, B.; Raabe, D.; Mianroodi, J.R. Accelerating phase-field-based simulation via machine learning. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.02121. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Q.; Yan, X.; Yin, S.; Li, X.; Liu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhuang, L. An extended version of cellular automata model for powder bed fusion to unravel the dependence of microstructure on printing areas for Inconel 625. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 73, 103676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, C.; Lundbäck, A. Modeling the Evolution of Grain Texture during Solidification of Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion Manufactured Alloy 625 Using a Cellular Automata Finite Element Model. Metals 2023, 13, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Wang, G.; Zhou, W.; Wei, L.; Lin, X.; Huang, W. Understanding grain evolution in laser powder bed fusion process through a real-time coupled Lattice Boltzmann model-Cellular Automaton simulation. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 321, 118126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastac, L. 3D Modeling of the Solidification Structure Evolution and of the Inter Layer/Track Voids Formation in Metallic Alloys Processed by Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. Materials 2022, 15, 8885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nastac, L. 3D Modeling of the Solidification Structure Evolution of Superalloys in Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing Processes. Metals 2021, 11, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.Y.; Kuesters, Y.K.; Logvinov, R.L.; Markl, M.M.; Körner, C.K. SAMPLE3D: A Versatile Numerical Tool for Investigating Texture and Grain Structure of Materials Processed by PBF Processes. In Proceedings of the IVth International Conference on Simulation for Additive Manufacturing (Sim-AM 2023), Munich, Germany, 26–28 July 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Maji, S.; Amirthalingam, M. Multi-component and multi-phase-field modelling of solidification microstructural evolution in Inconel 625 alloy during laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Weld. World 2025, 69, 1023–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okugawa, M.; Saito, K.; Yoshima, H.; Sawaizumi, K.; Nomoto, S.; Watanabe, M.; Nakano, T.; Koizumi, Y. Solute segregation in a rapidly solidified Hastelloy-X Ni-based superalloy during laser powder bed fusion investigated by phase-field and computational thermal-fluid dynamics simulations. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 84, 104079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadkamal, H.; Caiazzo, F. Numerical Study to Analyze the Influence of Process Parameters on Temperature and Stress Field in Powder Bed Fusion of Ti-6Al-4V. Materials 2025, 18, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denlinger, E.R.; Gouge, M.; Irwin, J.; Michaleris, P. Thermomechanical model development and in situ experimental validation of the Laser Powder-Bed Fusion process. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 16, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Lin, X.; Kang, N.; Ma, L.; Wei, L.; Zheng, M.; Yu, J.; Peng, D.; Huang, W. A novel high-efficient finite element analysis method of powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olleak, A.; Xi, Z. A study of modeling assumptions and adaptive remeshing for thermomechanical finite element modeling of the LPBF process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 115, 3599–3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Liang, X.; Hayduke, D.; Liu, J.; Cheng, L.; Oskin, J.; Whitmore, R.; To, A.C. An inherent strain based multiscale modeling framework for simulating part-scale residual deformation for direct metal laser sintering. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 28, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar, C.; Demir, E. A thermomechanical finite element model and its comparison to inherent strain method for powder-bed fusion process. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 54, 102708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ji, C.; Hou, Y.; Jin, P.; He, J.; Wu, J.; Li, K. Modified inherent strain method coupled with shear strain and dynamic mechanical properties for predicting residual deformation of Inconel 738LC part fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 203, 109163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Dong, W.; Chen, Q.; To, A.C. On incorporating scanning strategy effects into the modified inherent strain modeling framework for laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 37, 101648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Liang, X.; Chen, Q.; Hinnebusch, S.; Zhou, Z.; To, A.C. A new procedure for implementing the modified inherent strain method with improved accuracy in predicting both residual stress and deformation for laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 47, 102345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.; Elsen, R.S.; Abishai, D.; Narayan, M.J.; Sakthivel, A.R.; Chadha, U.; Hirpha, B.B. Prediction and Experimental Verification of Distortion due to Residual Stresses in a Ti-6Al-4V Control Arm Plate. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 2022, 5211623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Barrett, R.A.; Leen, S.B. Finite element modelling for mitigation of residual stress and distortion in macro-scale powder bed fusion components. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2023, 237, 1458–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassila, C.J.; Malmelöv, A.; Andersson, C.; Hektor, J.; Fisk, M.; Lundbäck, A.; Wiklund, U. Influence of Scanning Strategy on Residual Stresses in Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion Manufactured Alloy 718: Modeling and Experiments. Materials 2024, 17, 6265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmeri, D.; Pollara, G.; Licari, R.; Micari, F. Finite Element Method in L-PBF of Ti-6Al-4V: Influence of Laser Power and Scan Speed on Residual Stress and Part Distortion. Metals 2023, 13, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, N.; Chen, Y.-B.; Lee, M.-T. The Development of an Effective and Comprehensive Modeling Technique for Thermomechanical Analysis of Selective Laser Melting Process. In Proceedings of the Conference: International Conference of Asian Society for Precision Engineering and Nanotechnology, Hong Kong, China, 21–24 November 2023; pp. 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, B.; Dandekar, T.R.; Birosca, S. Probing the temperature field and residual stress transformation in multi-track, multi-layered system. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 38, 108056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangestani, R.; Sabiston, T.; Chakraborty, A.; Muhammad, W.; Yuan, L.; Martin, É. An Efficient Track-Scale Model for Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing: Part 1-Thermal Model. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 753040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, P.; Cianetti, F.; Pilerci, P. Parametric Finite Elements Model of SLM Additive Manufacturing process. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2018, 8, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonaet, A.M.; Park, H.S.; Myung, L.C. Prediction of residual stress and deformation based on the temperature distribution in 3D-printed parts. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 113, 2227–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.O.; Maiolini, A.S.F.R.; Miranda, F.; Farias, A.; Seriacopi, V.; Bordinassi, E.C.; Batalha, G.F. Numerical and Experimental Analysis of the Influence of Manufacturing Parameters in Additive Manufacturing SLM-PBF on Residual Stress and Thermal Distortion in Parts of Titanium Alloy Ti6Al4V. In Proceedings of the Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.; Shrestha, S.; Chou, K. Stress and deformation evaluations of scanning strategy effect in selective laser melting. Addit. Manuf. 2016, 12, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Zeng, C.; Xue, J. Scanning strategy optimization for the selective laser melting additive manufacturing of Ti6Al4V. Eng. Res. Express 2023, 5, 015041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Taylor, H.; Takezawa, A.; Liang, X.; Jimenez, X.; Wicker, R.; To, A.C. Island scanning pattern optimization for residual deformation mitigation in laser powder bed fusion via sequential inherent strain method and sensitivity analysis. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, M.A.L.; Dew, O.; Todd, I. Predictive process diagram for parameters selection in laser powder bed fusion to achieve high-density and low-cracking built parts. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 85, 104145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanth Kumar, R.K.; Boggarapu, N.R.; Narayana Murty, S.V.S. Multi-objective optimization to specify optimal selective laser melting process parameters for SS316 L powder. Multidiscip. Model. Mater. Struct. 2024, 20, 59–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, M.; Feng, S.; Brandon, L.; Donmez, A.; Moylan, S.; Fesperman, R. Measurement science needs for real-time control of additive manufacturing powder-bed fusion processes. In Additive Manufacturing Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 629–652. ISBN 9781315119106. [Google Scholar]

- Moges, T.; Ameta, G.; Witherell, P. A Review of Model Inaccuracy and Parameter Uncertainty in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Models and Simulations. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Trans. ASME 2019, 141, 040801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwania, F.M.; Maringa, M.; van der Walt, J. Analytical and numerical modelling of laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) of polymers—A review of the key areas of focus of the process. MATEC Web Conf. 2022, 370, 06001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puso, M.A.; Hodge, N.E. An assessment of the utility of multirate time integration for the modeling of laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 73, 103657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, M. Review of Particle-Based Computational Methods and Their Application in the Computational Modelling of Welding, Casting and Additive Manufacturing. Metals 2023, 13, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrasiabi, M.; Lüthi, C.; Bambach, M.; Wegener, K. Multi-resolution SPH simulation of a laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing process. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wu, C.Y. Modelling Complex Particle–Fluid Flow with a Discrete Element Method Coupled with Lattice Boltzmann Methods (DEM-LBM). ChemEngineering 2020, 4, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.N.; Lo, Y.L.; Hung, W. Coupled Computational Fluid Dynamics-Discrete Element Method Model for Investigation of Powder Effects in Nonconventional Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 11, e1656–e1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svyetlichnyy, D.; Krzyzanowski, M.; Straka, R.; Lach, L.; Rainforth, W.M. Application of cellular automata and Lattice Boltzmann methods for modelling of additive layer manufacturing. Int. J. Numer. Methods Heat Fluid Flow 2018, 28, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Seede, R.; Whitt, A.; Shoukr, D.; Huang, X.; Karaman, I.; Arroyave, R.; Elwany, A. A printability assessment framework for fabricating low variability nickel-niobium parts using laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2021, 27, 1737–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holla, V.; Lane, B.; Redford, J.; Kopp, P.; Kollmannsberger, S.; Article, R. Quantifying Thermal Model Accuracy in PBF-LB/M using Statistical Similarity Tests Against Thermographic Measurements. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Lu, Y.; Jones, K.; Yang, Z.; Fox, J.; Witherell, P.; Wagner, G.; Liu, W.K. Data-driven characterization of thermal models for powder-bed-fusion additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imani Shahabad, S.; Karimi, G.; Toyserkani, E. An Extended Rosenthal’s Model for Laser Powder-Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing: Energy Auditing of Thermal Boundary Conditions. Lasers Manuf. Mater. Process. 2021, 8, 288–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zagade, P.R.; Gautham, B.P.; De, A.; DebRoy, T. Analytical modelling of scanning strategy effect on temperature field and melt track dimensions in laser powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 82, 104046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.R.; Sinclair, C.W.; Maijer, D.M. Incorporating non-linear effects in fast semi-analytical thermal modelling of powder bed fusion. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.03018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.A.; Ur Rehman, A.; Khan, T.; Seers, T.D.; Liou, F.; Khraisheh, M. Defects quantification of additively manufactured AISI 316L stainless steel parts via non-destructive analyses: Experiments and semi-FEM-analytical-based modeling. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 174, 110684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.J.; Dai, H.L.; Yao, Y.; Liu, J.L. A semi-analytical model for rapid prediction of residual stress and deformation in laser powder bed fusion. Appl. Math. Model. 2024, 125, 672–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olleak, A.; Xi, Z. Efficient LPBF process simulation using finite element modeling with adaptive remeshing for distortions and residual stresses prediction. Manuf. Lett. 2020, 24, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilani, M.A.; Banad, Y.M. Modeling Melt Pool Geometry in Metal Additive Manufacturing Using Goldak’s Semi-Ellipsoidal Heat Source: A Data-driven Computational Approach. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.08834. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J. On efficiency and effectiveness of finite volume method for thermal analysis of selective laser melting. Eng. Comput. 2020, 37, 2155–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, W.; Chams, A. Discrete Element Method framework to simulate metallic Laser Powder-Bed Fusion additive manufacturing process. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Conference on Computational Structures Technology; Civil-Comp Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2023; Volume 3, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouraytem, N.; Li, X.; Tan, W.; Kappes, B.; Spear, A.D. Modeling process–structure–property relationships in metal additive manufacturing: A review on physics-driven versus data-driven approaches. J. Phys. Mater. 2021, 4, 032002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Guo, Y.B. Computational modeling and physics-informed machine learning of metal additive manufacturing: State-of-the-art and future perspective. Annu. Rev. Heat Transf. 2021, 24, 303–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riensche, A.; Bevans, B.; King, G.; Krishnan, A.; Cole, K.; Rao, P. Predicting Microstructure Evolution in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing Using Physics-Based Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the ASME 2024 19th International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference, MSEC 2024, Knoxville, TN, USA, 17–21 June 2024; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Moges, T.; Yang, Z.; Jones, K.; Feng, S.; Witherell, P.; Lu, Y. Hybrid Modeling Approach for Melt-Pool Prediction in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2021, 21, 050902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Xue, T.; Jeong, J.; Webster, S.; Ehmann, K.; Cao, J. Hybrid thermal modeling of additive manufacturing processes using physics-informed neural networks for temperature prediction and parameter identification. Comput. Mech. 2023, 72, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Fé-Perdomo, I.; Ramos-Grez, J.A. An insight into adiabatic efficiency hybrid modeling in Laser-Based Powder Bed Fusion of 316L stainless steel. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 161, 109203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ZainElabdeen, I.H.; Ismail, L.; Mohamed, O.F.; Khan, K.A.; Schiffer, A. Recent advancements in hybrid additive manufacturing of similar and dissimilar metals via laser powder bed fusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 909, 146833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Wei, K.; Liu, M.; Song, W.; Li, X.; Zeng, X. Microstructure and mechanical properties of AlSi10Mg alloy built by laser powder bed fusion/direct energy deposition hybrid laser additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 59, 103160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauch, M.; Hascoet, J.Y. Opening New Opportunities For Aeronautic, Naval And Train Large Components Realization With Hybrid And Twin Manufacturing. J. Mach. Eng. 2022, 22, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyda, A.; Arizmendi, M.; Ruiz de Galarreta, S.; Rodriguez-Florez, N.; Jimenez, A. Meeting high precision requirements of additively manufactured components through hybrid manufacturing. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 40, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabalo, M.A.; García-Domínguez, A.; Rubio, E.M.; Marín, M.M.; Agustina, B. Last Trends in the Application of the Hybrid Additive and Subtractive Manufacturing in the Aeronautic Industry. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 132, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafenecker, J.; Bartels, D.; Kuball, C.M.; Kreß, M.; Rothfelder, R.; Schmidt, M.; Merklein, M. Hybrid process chains combining metal additive manufacturing and forming—A review. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 46, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidare, P.; Jiménez, A.; Abdelkhalek, S.M.; Khaled, I.; Hassan, A.; Abdallah, R.; Essa, K. Hybrid additive manufacturing of AISI H13 through interlayer machining and laser re-melting. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 37, 107042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, D.; Hornung, S.; Esen, C.; Hellmann, R. Optimization of mechanical properties of additive manufactured IN 718 parts combining LPBF and in-situ high-speed milling. In Proceedings of the Laser 3D Manufacturing XI, San Francisco, CA, USA, 27 January–1 February 2024; Volume 12876, pp. 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, D.; Esen, C.; Hellmann, R. Static and Dynamic Mechanical Behaviour of Hybrid-PBF-LB/M-Built and Hot Isostatic Pressed Lattice Structures. Materials 2023, 16, 3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letenneur, M.; Kreitcberg, A.; Brailovski, V. Optimization of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Processing Using a Combination of Melt Pool Modeling and Design of Experiment Approaches: Density Control. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2019, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabassum, R.; Uz Zaman, U.K.; Ahmed Baqai, A.; Rehman Mazhar, A.; Ullah Butt, S. Hybrid Additive Manufacturing: A Review from a Process Planning Perspective. J. Adv. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 23, 227–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajadi, P.; Rahmani Dehaghani, M.; Tang, Y.; Wang, G.G. Physics-Informed Online Learning for Temperature Prediction in Metal AM. Materials 2024, 17, 3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Guo, Y.B.; Raissi, M.; Guo, W.G. Physics-Informed Machine Learning of Argon Gas-Driven Melt Pool Dynamics. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2024, 146, 081008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghungrad, S.; Faegh, M.; Gould, B.; Wolff, S.J.; Haghighi, A. Architecture-Driven Physics-Informed Deep Learning for Temperature Prediction in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing with Limited Data. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2023, 145, 081007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Xia, M.; Hu, Y. Physics-Informed Machine Learning for Accurate Prediction of Temperature and Melt Pool Dimension in Metal Additive Manufacturing. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 11, e1679–e1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Yan, J. Machine learning for metal additive manufacturing: Predicting temperature and melt pool fluid dynamics using physics-informed neural networks. Comput. Mech. 2021, 67, 619–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Mahadevan, S. Probabilistic predictive control of porosity in laser powder bed fusion. J. Intell. Manuf. 2023, 34, 1085–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Li, X.; Rajanna, M.R.; Reutzel, E.W.; Sawyer, B.; Rao, P.; Lua, J.; Phan, N.; Yu, Y. Deep Neural Operator Enabled Digital Twin Modeling for Additive Manufacturing. Adv. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2024, 2, 174–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.A.; Khraisheh, M.; Popescu, A.C.; Liou, F. Processing windows for Al-357 by LPBF process: A novel framework integrating FEM simulation and machine learning with empirical testing. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2024, 30, 1846–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, A.; Giera, B.; Guss, G.M.; Forien, J.B.; Matthews, M.J.; Rao, P. Heterogeneous sensing and scientific machine learning for quality assurance in laser powder bed fusion—A single-track study. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 36, 101659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, R.; Zhou, J.; Dai, C.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Q. Physics-Based Data Augmentation Enables Accurate Machine Learning Prediction of Melt Pool Geometry. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 8587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Cristino, V.A.M.; Kwok, C.T.; Wei, Q.; Tang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H. Deepening the scientific understanding of different phenomenology in laser powder bed fusion by an integrated framework. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2023, 216, 124596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, R.E.; Mukherjee, T.; Chuang, C.; Phan, T.Q.; Debroy, T.; Pagan, D.C.; Keckes, J. Combining synchrotron X-ray diffraction, mechanistic modeling and machine learning for in situ subsurface temperature quantification during laser melting. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2023, 56, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Yang, Z.; Lu, Y. A physics-guided deep generative model for predicting melt pool behavior in laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 36, 5715–5735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Qiu, Y.; Liu, W.; Qiu, X.; Bai, Q. Defect prediction in laser powder bed fusion with the combination of simulated melt pool images and thermal images. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 106, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twumasi, A.; Roy, P.C.; Choi, J.Y.; Gan, Z. Brief Paper: Physics-Guided Scan Paths Optimization for Controlled Microstructure in Laser Powder Bed Fusion. In Proceedings of the ASME 2024 19th International Manufacturing Science and Engineering Conference, MSEC 2024, Knoxville, TN, USA, 17–21 June 2024; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Riensche, A.R.; Bevans, B.D.; King, G.; Krishnan, A.; Cole, K.D.; Rao, P. Predicting meltpool depth and primary dendritic arm spacing in laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing using physics-based machine learning. Mater. Des. 2024, 237, 112540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penny, R.W.; John Hart, A. Radiometric Temperature Measurement for Metal Additive Manufacturing via Temperature Emissivity Separation. Addit. Manuf. 2025, 110, 104904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surana, A.; Lynch, M.E.; Nassar, A.R.; Ojard, G.C.; Fisher, B.A.; Corbin, D.; Overdorff, R. Flaw Detection in Multi-Laser Powder Bed Fusion Using in Situ Coaxial Multi-Spectral Sensing and Deep Learning. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2023, 145, 051005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croset, G.; Martin, G.; Josserond, C.; Lhuissier, P.; Blandin, J.J.; Dendievel, R. In-situ layerwise monitoring of electron beam powder bed fusion using near-infrared imaging. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 38, 101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, S.; Fritsch, T.; Ulbricht, A.; Mohr, G.; Bruno, G.; Maierhofer, C.; Altenburg, S.J. On the Registration of Thermographic In Situ Monitoring Data and Computed Tomography Reference Data in the Scope of Defect Prediction in Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Metals 2022, 12, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrazas-Nájera, C.A.; Fernández, A.; Felice, R.; Wicker, R. On the thermal emissive behavior of four common alloys processed via powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 82, 104023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, B.; Castro, A.; Jaquemetton, L.; Beckett, D. Thermal calibration of ratiometric, on-axis melt pool monitoring photodetector system using tungsten strip lamp. Mater. Eval. 2022, 80, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, B.; Jacquemetton, L.; Piltch, M.; Beckett, D. Thermal Calibration of Commercial Melt Pool Monitoring Sensors on a Laser Powder Bed Fusion System; US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, G.; Altenburg, S.J.; Ulbricht, A.; Heinrich, P.; Baum, D.; Maierhofer, C.; Hilgenberg, K. In-Situ Defect Detection in Laser Powder Bed Fusion by Using Thermography and Optical Tomography—Comparison to Computed Tomography. Metals 2020, 10, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrich, J.; Snow, Z.; Corbin, D.; Reutzel, E.W. Multi-modal sensor fusion with machine learning for data-driven process monitoring for additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 48, 102364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow, Z.; Amir, L.S.; Ziabari, K.; Fisher, B.; Paquit, V. Machine Learning Enabled Sensor Fusion for In Situ Defect Detection in Laser Powder Bed Fusion CRADA Final Report; Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL): Oak Ridge, TN, USA; RTX Technology Research Center: East Hartford, CT, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, Z.; Scime, L.; Ziabari, A.; Fisher, B.; Paquit, V. Scalable in situ non-destructive evaluation of additively manufactured components using process monitoring, sensor fusion, and machine learning. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 78, 103817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ero, O.; Taherkhani, K.; Hemmati, Y.; Toyserkani, E. An integrated fuzzy logic and machine learning platform for porosity detection using optical tomography imaging during laser powder bed fusion. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 2024, 6, 065601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Walker, J.; Middendorf, J.; Spears, T.; Maass, D.; Dunne, B. Deep-learning-based multisensor fusion for in situ defect prediction in additive manufacturing. In Proceedings of the Applications of Machine Learning 2025, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 14–16 February 2025; Volume 13606, pp. 105–119. [Google Scholar]

- Bonato, N.; Zanini, F.; Carmignato, S. Deformations modelling of metal additively manufactured parts and improved comparison of in-process monitoring and post-process X-ray computed tomography. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 75, 103736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.; Felice, R.; Terrazas-Nájera, C.A.; Wicker, R. Implications for accurate surface temperature monitoring in powder bed fusion: Using multi-wavelength pyrometry to characterize spectral emissivity during processing. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 46, 102138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höfflin, D.; Sauer, C.; Schiffler, A.; Manara, J.; Hartmann, J. Pixelwise high-temperature calibration for in-situ temperature measuring in powder bed fusion of metal with laser beam. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Standfield, B.; Dou, C.; Law, A.C.; Kong, Z.J. Real-time process monitoring and closed-loop control on laser power via a customized laser powder bed fusion platform. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 66, 103449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, M.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital Twin Driven Smart Manufacturing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9780128176306. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Li, W.; Nguyen, Q.B.; An, X.; Lu, W.; Li, Z.; Ng, F.L.; Ling Nai, S.M.; Wei, J. Enhanced strength–ductility synergy and transformation-induced plasticity of the selective laser melting fabricated 304L stainless steel. Addit. Manuf. 2020, 35, 101300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colosimo, B.M.; Grasso, M. In-situ monitoring in L-PBF: Opportunities and challenges. Procedia CIRP 2020, 94, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, R.; Obeidi, M.A.; Hughes, C.; McCarthy, É.; Egan, D.S.; Vijayaraghavan, R.K.; Joshi, A.M.; Garzon, V.A.; Dowling, D.P.; McNally, P.J.; et al. In-situ sensing, process monitoring and machine control in Laser Powder Bed Fusion: A review. Addit. Manuf. 2021, 45, 102058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, K.I.K.; Huang, H.; Xu, X. Digital Twin-driven smart manufacturing: Connotation, reference model, applications and research issues. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2020, 61, 101837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, P.; Mahadevan, S. Probabilistic Digital Twin for Additive Manufacturing Process Design and Control. J. Mech. Des. 2022, 144, 091704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, G.; Elwany, A. A Review on Process Monitoring and Control in Metal-Based Additive Manufacturing. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. Trans. ASME 2014, 136, 060801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everton, S.K.; Hirsch, M.; Stavroulakis, P.I.; Leach, R.K.; Clare, A.T. Review of in-situ process monitoring and in-situ metrology for metal additive manufacturing. Mater. Des. 2016, 95, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, U.; Khan, M.; Khalid, A.; Lughmani, W.A. Human-Centric Digital Twins in Industry: A Comprehensive Review of Enabling Technologies and Implementation Strategies. Sensors 2023, 23, 3938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, C.; Xu, X. Visualisation of the Digital Twin data in manufacturing by using Augmented Reality. Procedia CIRP 2019, 81, 898–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritzinger, W.; Karner, M.; Traar, G.; Henjes, J.; Sihn, W. Digital Twin in manufacturing: A categorical literature review and classification. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2018, 51, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, A.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital Twin in Industry: State-of-the-Art. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 2405–2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaikwad, A.; Yavari, R.; Montazeri, M.; Cole, K.; Bian, L.; Rao, P. Toward the digital twin of additive manufacturing: Integrating thermal simulations, sensing, and analytics to detect process faults. IISE Trans. 2020, 52, 1204–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhou, Q.; Cao, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, J. A convolutional neural network-based multi-sensor fusion approach for in-situ quality monitoring of selective laser melting. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 64, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Vallabh, C.K.P.; Zhao, X. Registration and fusion of large-scale melt pool temperature and morphology monitoring data demonstrated for surface topography prediction in LPBF. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 58, 103075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, K.J.; Ciardi, T.G.; Yamamoto, R.; Lu, M.; Nihar, A.; Jimenez, J.C.; Tripathi, P.K.; Giera, B.; Forien, J.B.; Lewandowski, J.J.; et al. L-PBF High-Throughput Data Pipeline Approach for Multi-modal Integration. Integr. Mater. Manuf. Innov. 2024, 13, 758–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Bi, G.; Yao, X.; Su, J.; Tan, C.; Feng, W.; Benakis, M.; Chew, Y.; Moon, S.K. In-situ process monitoring and adaptive quality enhancement in laser additive manufacturing: A critical review. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 74, 527–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorgannejad, S.; Martin, A.A.; Nicolino, J.W.; Strantza, M.; Guss, G.M.; Khairallah, S.; Forien, J.B.; Thampy, V.; Liu, S.; Quan, P.; et al. Localized keyhole pore prediction during laser powder bed fusion via multimodal process monitoring and X-ray radiography. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 78, 103810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gobert, C.; Ferguson, K.; Abranovic, B.; Chen, H.; Beuth, J.L.; Rollett, A.D.; Kara, L.B. Inference of highly time-resolved melt pool visual characteristics and spatially-dependent lack-of-fusion defects in laser powder bed fusion using acoustic and thermal emission data. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 83, 104057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandecasteele, M.; Searle, S.; Iuso, D.; Nourazar, M.; Ahar, A.; Hamidi Nasab, M.; Vrancken, B.; Booth, B. A High-speed Multimodal In-situ Monitoring System For Detecting Porosity And Deformation Defects In The Powder Bed Fusion Of Metallic Parts. In Proceedings of the Euro Powder Metallurgy 2025 Congress & Exhibition, Glasgow, UK, 14–17 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Yang, F.; Lv, C.; Liu, C.; Tang, W.; Yang, J. In-Situ Quality Intelligent Classification of Additively Manufactured Parts Using a Multi-Sensor Fusion Based Melt Pool Monitoring System. Addit. Manuf. Front. 2024, 3, 200153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scime, L.; Joslin, C.; Collins, D.A.; Sprayberry, M.; Singh, A.; Halsey, W.; Duncan, R.; Snow, Z.; Dehoff, R.; Paquit, V. A Data-Driven Framework for Direct Local Tensile Property Prediction of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Parts. Materials 2023, 16, 7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Yao, X.; Liu, K.; Tan, C.; Moon, S.K. Multisensor fusion-based digital twin in additive manufacturing for in-situ quality monitoring and defect correction. Proc. Des. Soc. 2023, 3, 2755–2764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, G.; Kim, J.; Yang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Lane, B.; Yeung, H. Multi-Scale Model Predictive Control for Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the ASME 2024 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 25–28 August 2024; Volume 2B-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estalaki, S.M.; Lough, C.S.; Landers, R.G.; Kinzel, E.C.; Luo, T. Predicting defects in laser powder bed fusion using in-situ thermal imaging data and machine learning. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 58, 103008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubrov, A.V.; Mirzade, F.K.; Dubrov, V.D. On modeling of heat transfer and molten pool behavior in multi-layer and multi-track laser additive manufacturing process. In Proceedings of the SPIE 11057, Modeling Aspects in Optical Metrology VII; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2019; Volume 11057, pp. 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, A.; Bayat, M.; Hattel, J. Multiphysics modeling of metal based additive manufacturing processes with focus on thermomechanical conditions. J. Therm. Stress. 2023, 46, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevans, B.D.; Riensche, A.; Carrington, A.; Deshmukh, K.; Darji, M.; Plotnikov, Y.; Sions, J.; Snyder, K.; Hass, D.; Rao, P. In-Process Monitoring of Part Quality in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing Process Using Acoustic Emission Sensors. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2025, 147, 061010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Guss, G.M.; Wilson, A.C.; Hau-Riege, S.P.; DePond, P.J.; McMains, S.; Matthews, M.J.; Giera, B. Machine-Learning-Based Monitoring of Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2018, 3, 1800136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Zhai, X.; Wang, K.; Zhang, K.; Wu, D.; Nazir, A.; Jiang, J.; Liao, W.H. Big data, machine learning, and digital twin assisted additive manufacturing: A review. Mater. Des. 2024, 244, 113086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, S.; Breese, P.P.; Ulbricht, A.; Mohr, G.; Altenburg, S.J. A deep learning framework for defect prediction based on thermographic in-situ monitoring in laser powder bed fusion. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 35, 1687–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Liu, S.; Zhang, X. A physics-informed machine learning model for porosity analysis in laser powder bed fusion additive manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 113, 1943–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.; Love, A.; Behseresht, S.; Pastrana, O.V.; Sakai, J. Digital Twin Development for Additive Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the ASME 2024 Pressure Vessels & Piping Conference, Bellevue, WA, USA, 28 July–2 August 2024; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horr, A.M. Real-time Modelling and ML Data Training for Digital Twinning of Additive Manufacturing Processesa? BHM Berg Hüttenmännische Monatshefte 2023, 169, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehab, E.; Jumassultan, A.; Khoyashov, N.; Juziyeva, S.; Jyeniskhan, N.; Ali, H. Data-Driven Digital Twin Requirements for Additive Layer Manufacturing. MATEC Web Conf. 2024, 401, 02012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Huang, S.; Song, Z.; Gao, Y.; Wu, J. A deep mixed-effects modeling approach for real-time monitoring of metal additive manufacturing process. IISE Trans. 2024, 56, 945–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatheodorou, A.; Papadimitriou, N.; Stathatos, E.; Benardos, P.; Vosniakos, G.C. Recent Advances in Sensor Fusion Monitoring and Control Strategies in Laser Powder Bed Fusion: A Review. Machines 2025, 13, 820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, Y. Transfer learning-based quality monitoring of laser powder bed fusion across materials. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 252, 124150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Yang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Hong, G.S. Self-Supervised Multilabel Melt Pool Anomaly Classification in Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. J. Comput. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2025, 25, 071006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]