Durability and Microstructural Evolution of PVA-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Under Coupled Sulfate Attack and Freeze–Thaw Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Experimental Mix Design

2.3. Specimen Preparation and Curing

2.4. Test Method

2.4.1. Sulfate-Freeze–Thaw Coupled Test

- (a)

- Quality Loss Rate

- (b)

- Relative dynamic modulus of elasticity

- (c)

- Compressive strength loss rate of cubes

- (d)

- Rate of splitting tensile strength loss

2.4.2. Microstructural Analysis

- (a)

- Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

- (b)

- X-ray diffraction (XRD)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Apparent Morphology

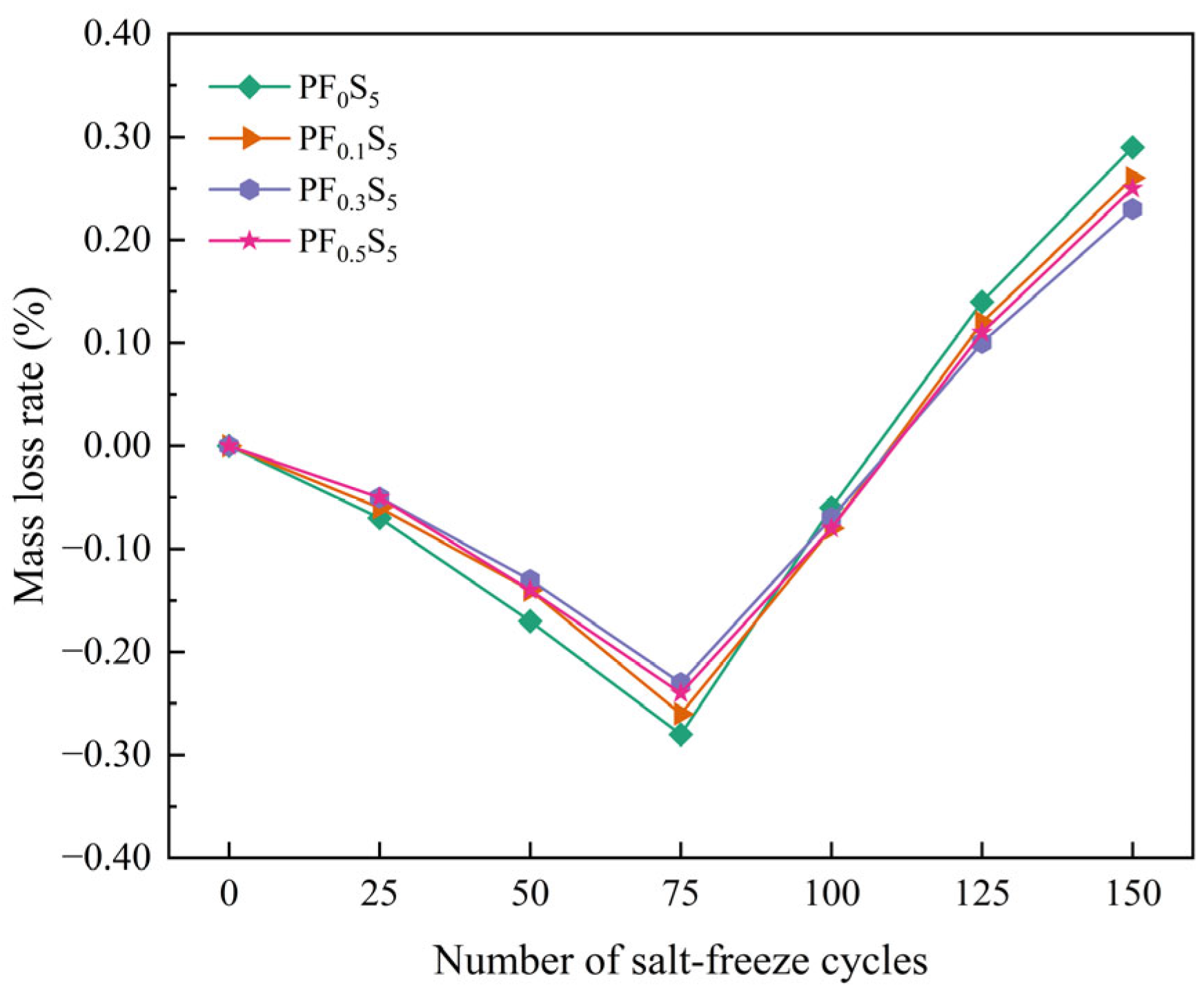

3.2. Quality

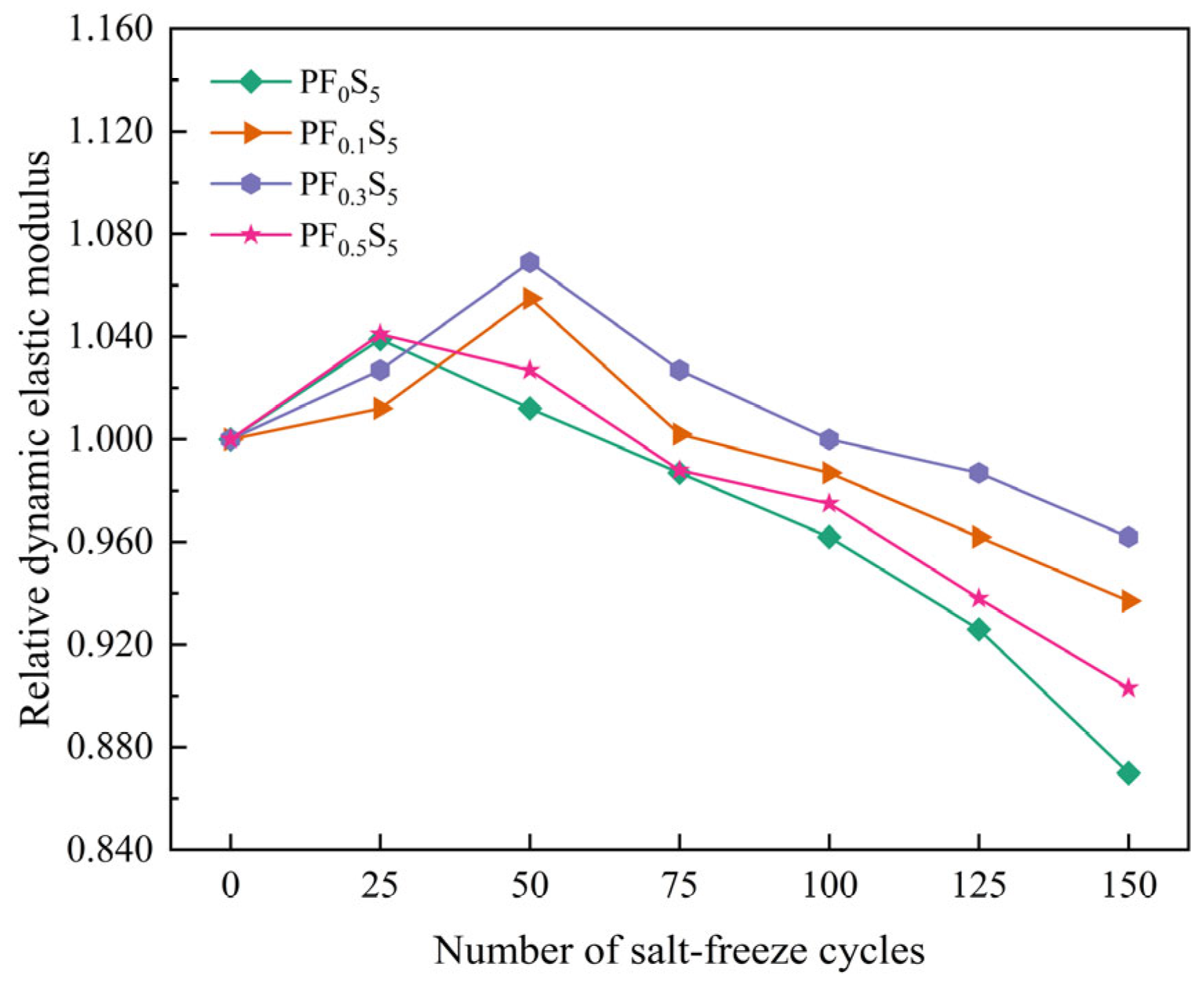

3.3. Relative Dynamic Elastic Modulus

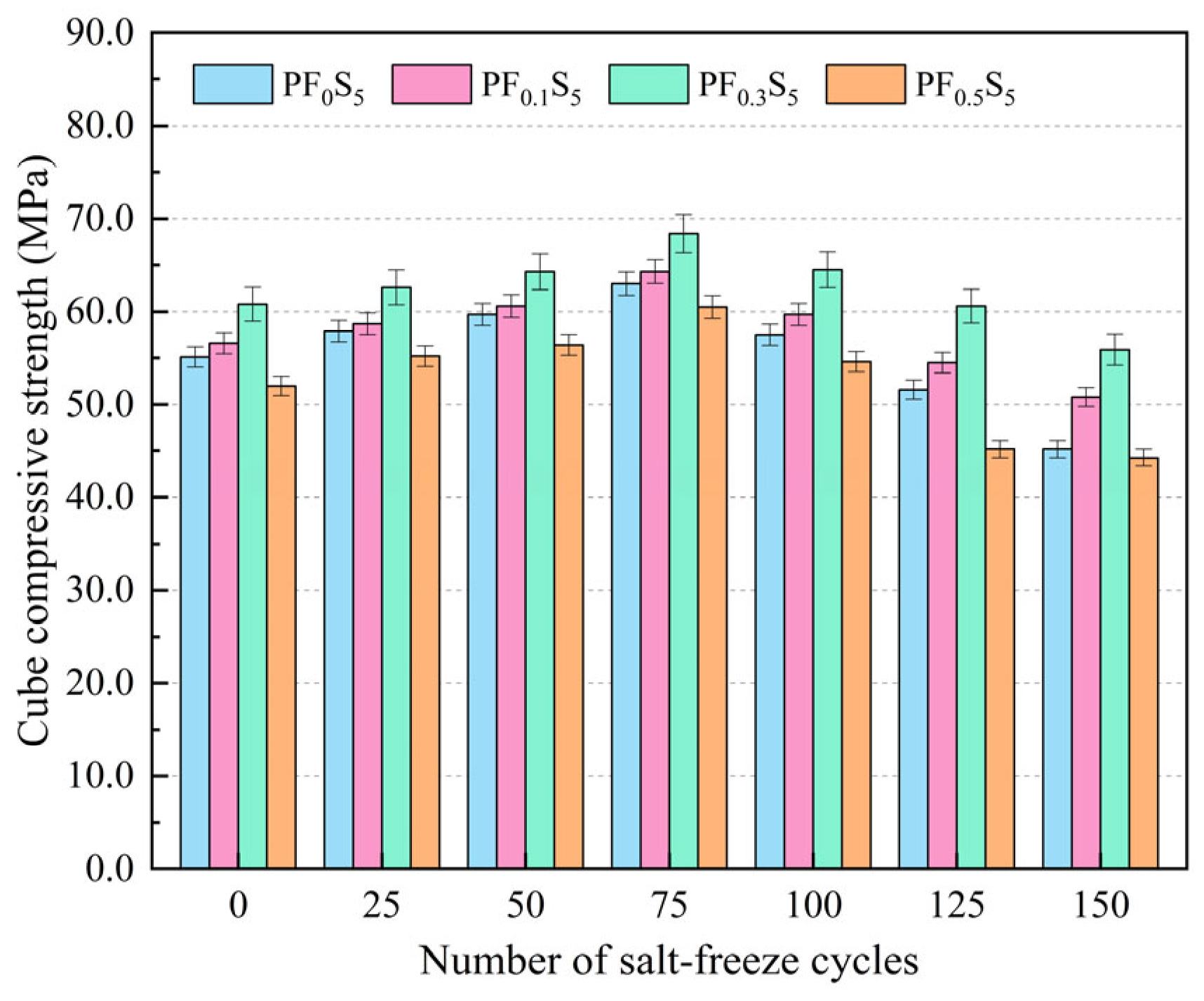

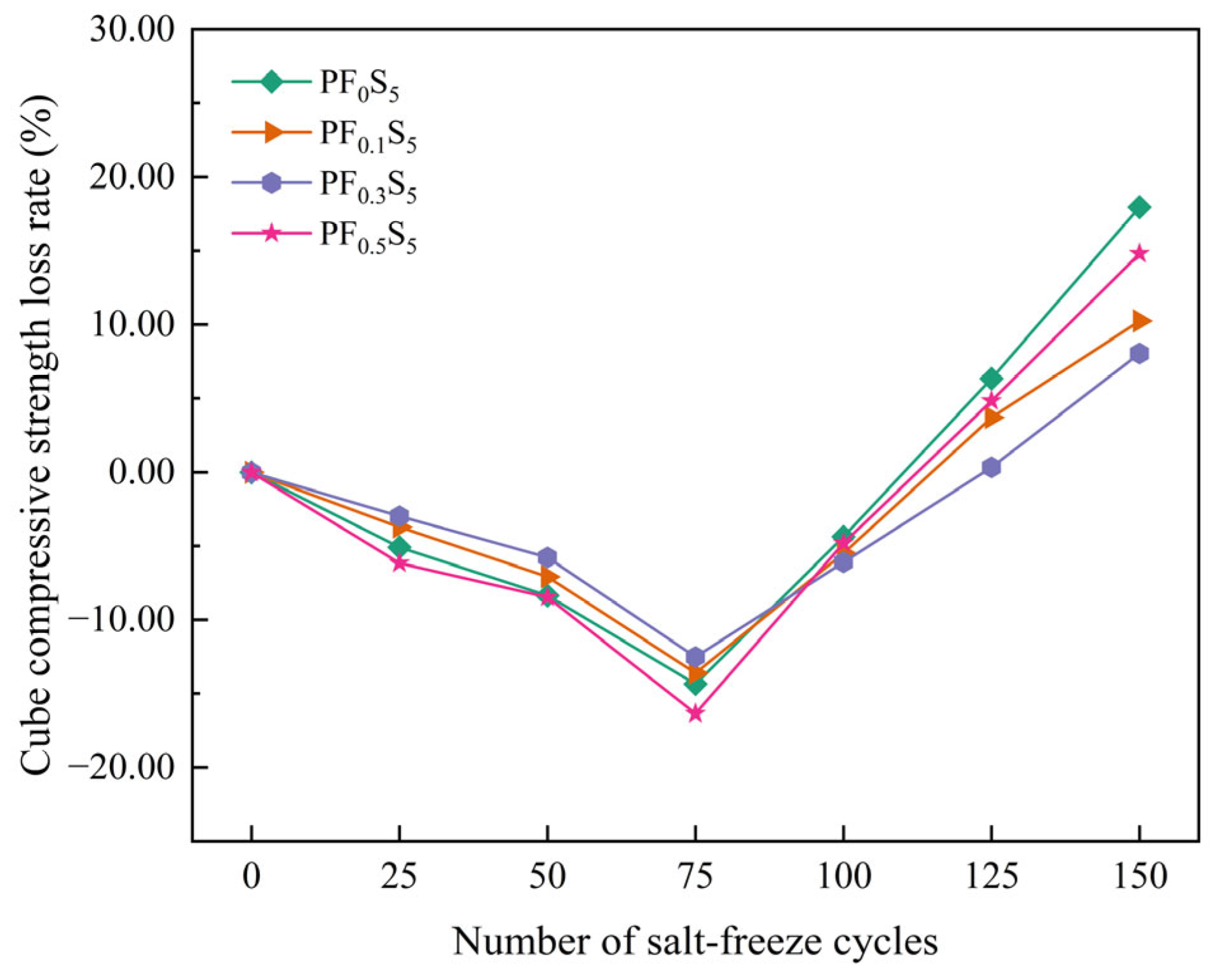

3.4. Cube Compressive Strengths

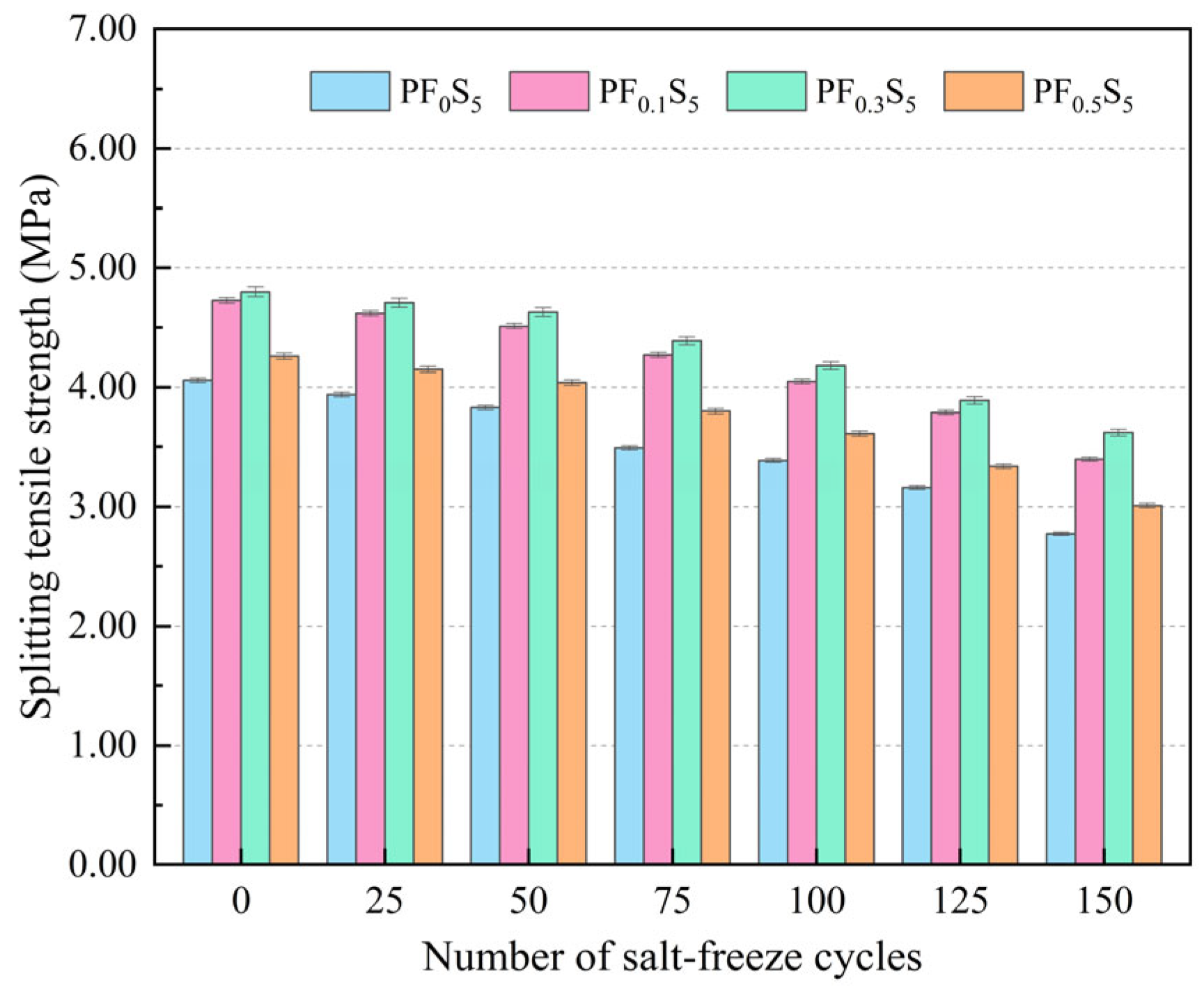

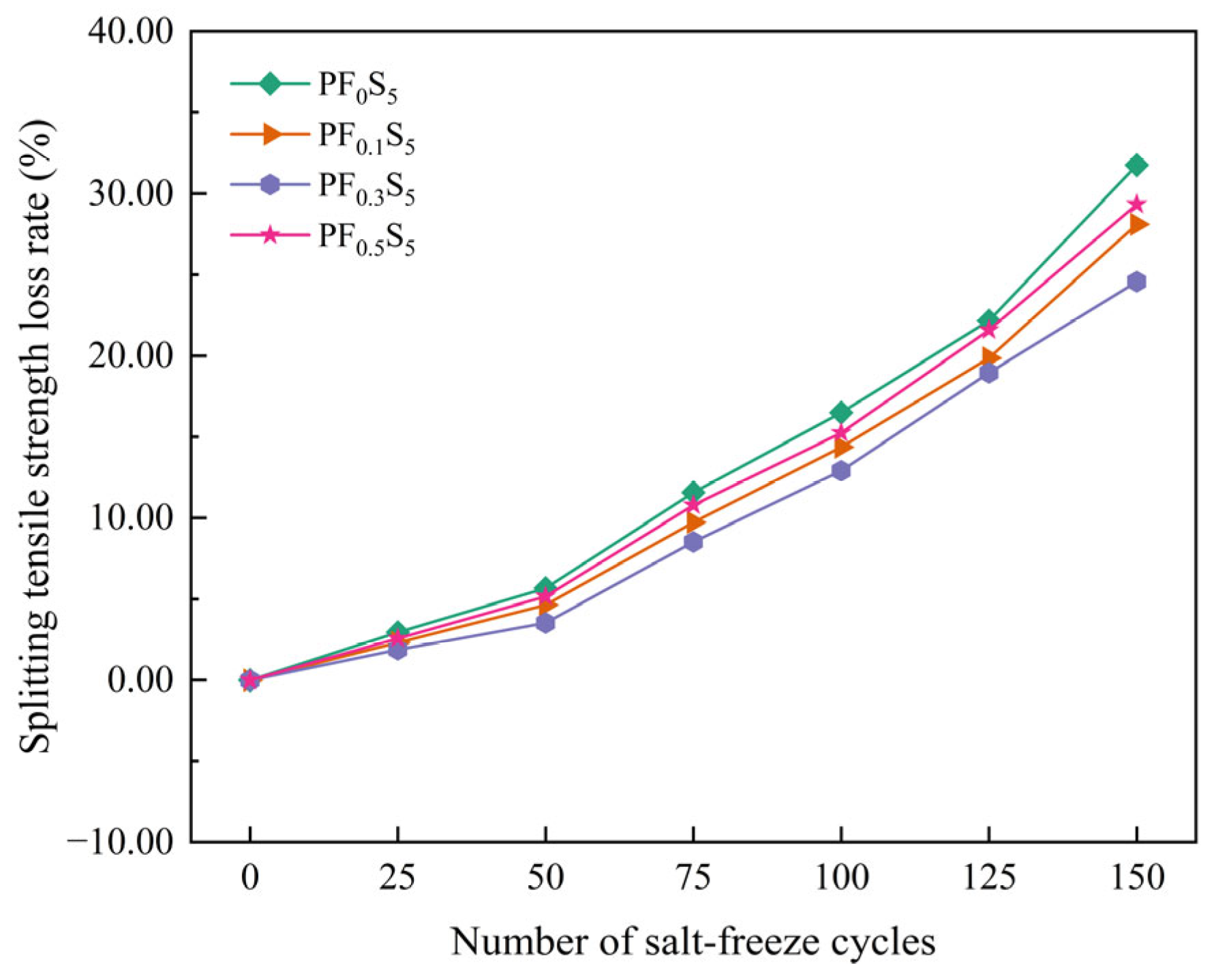

3.5. Splitting Tensile Strength

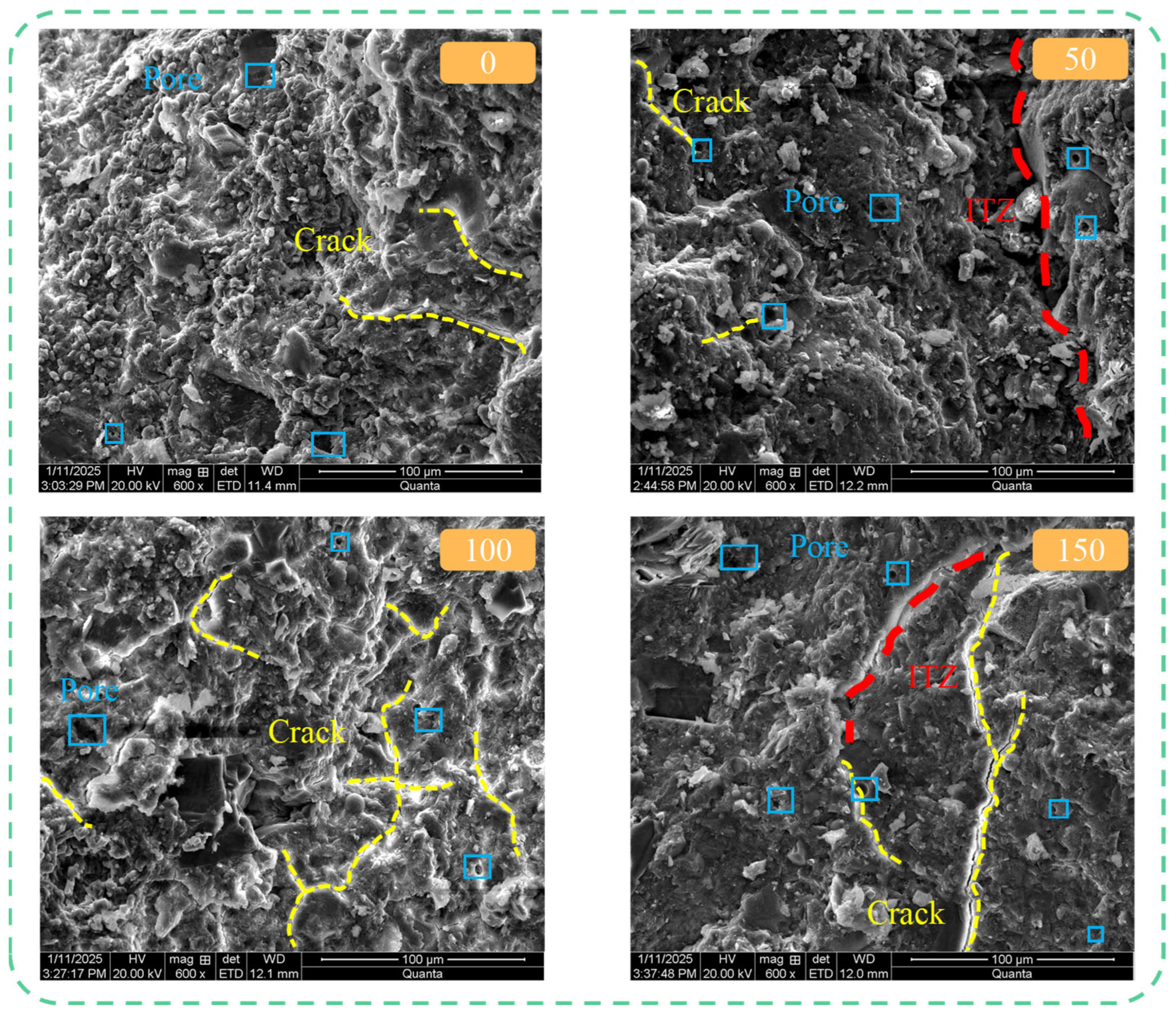

3.6. SEM Analysis

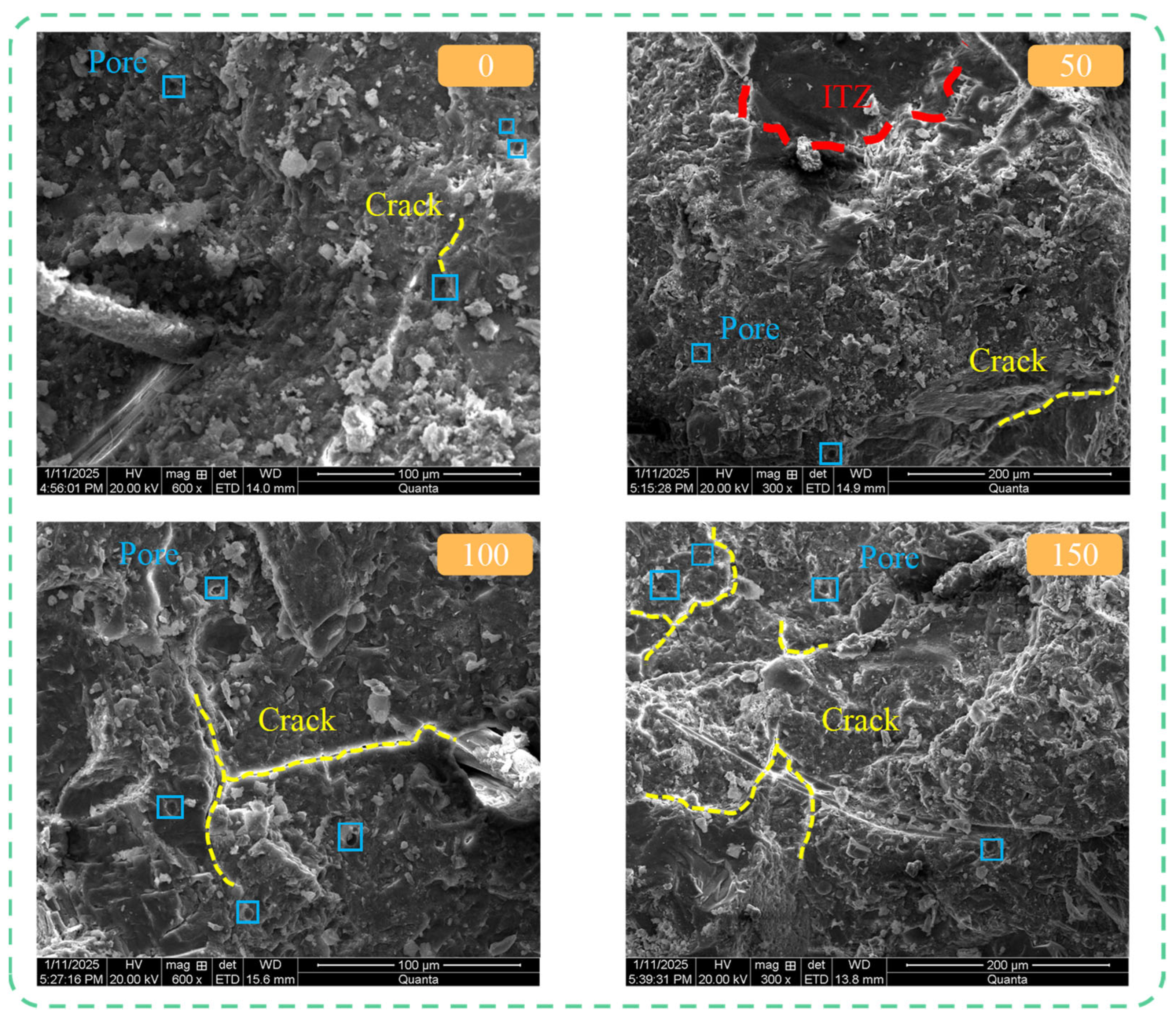

3.6.1. Effect of Salt-Freeze Cycles on Concrete Microstructure

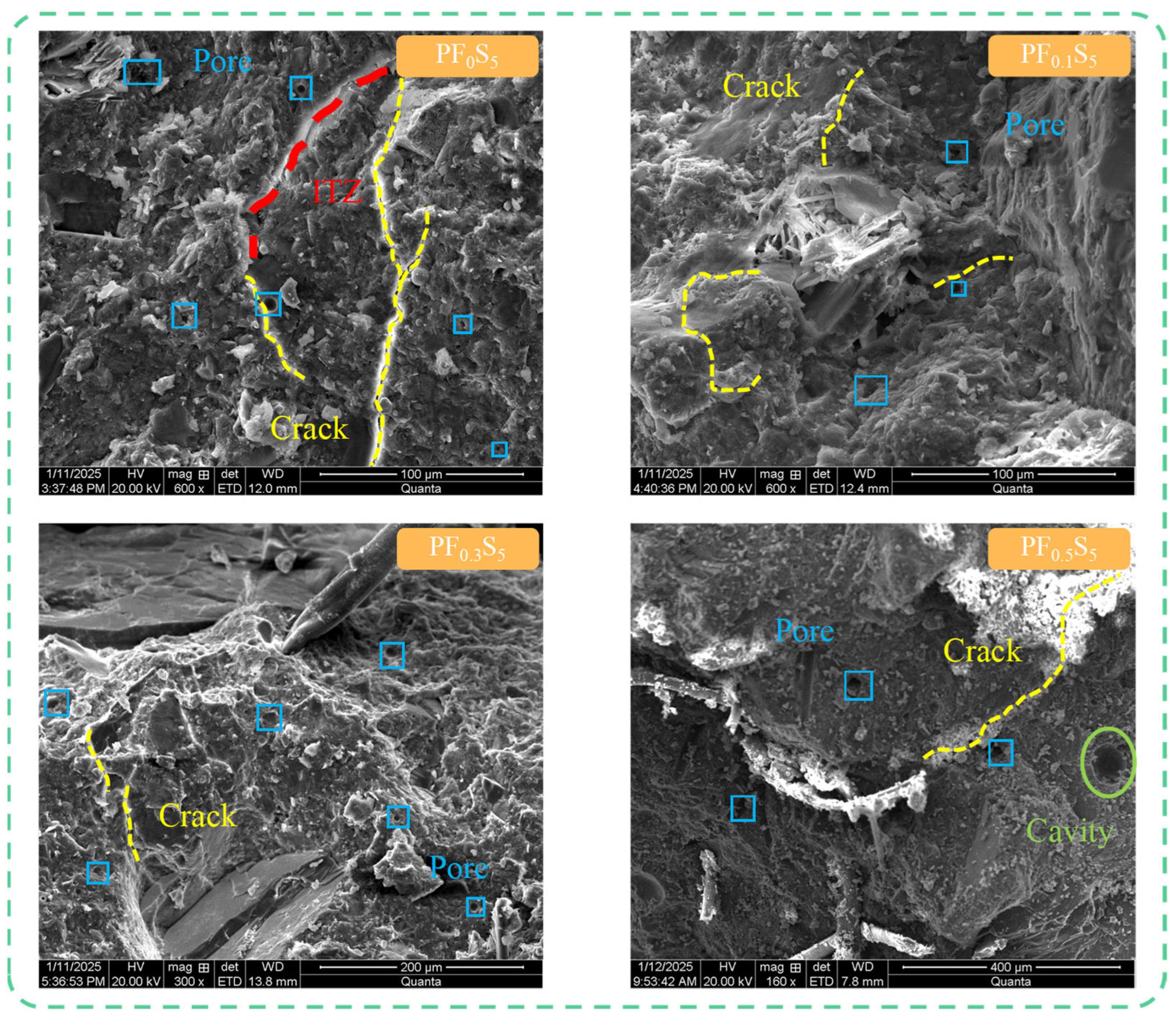

3.6.2. Effect of PVA Fiber Volume Content on Concrete Microstructure

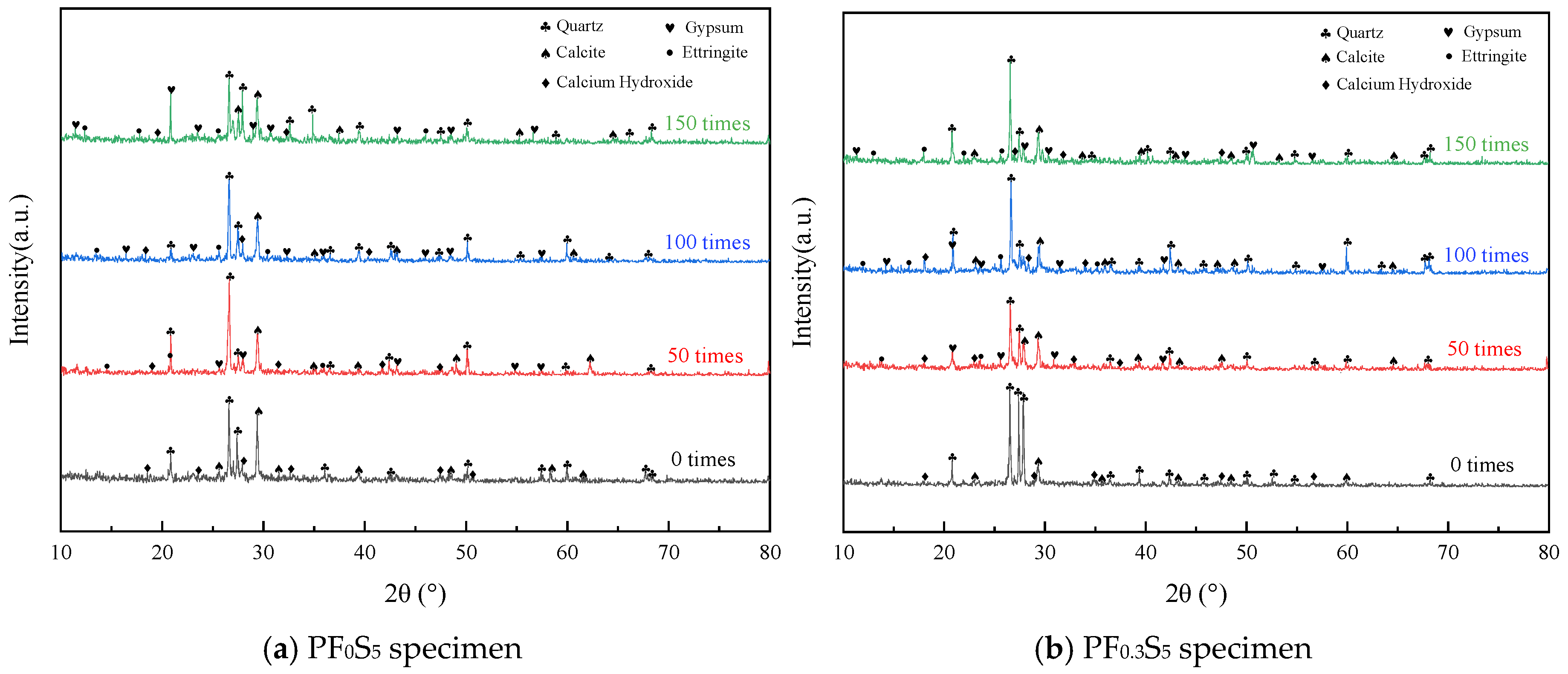

3.7. XRD Analysis

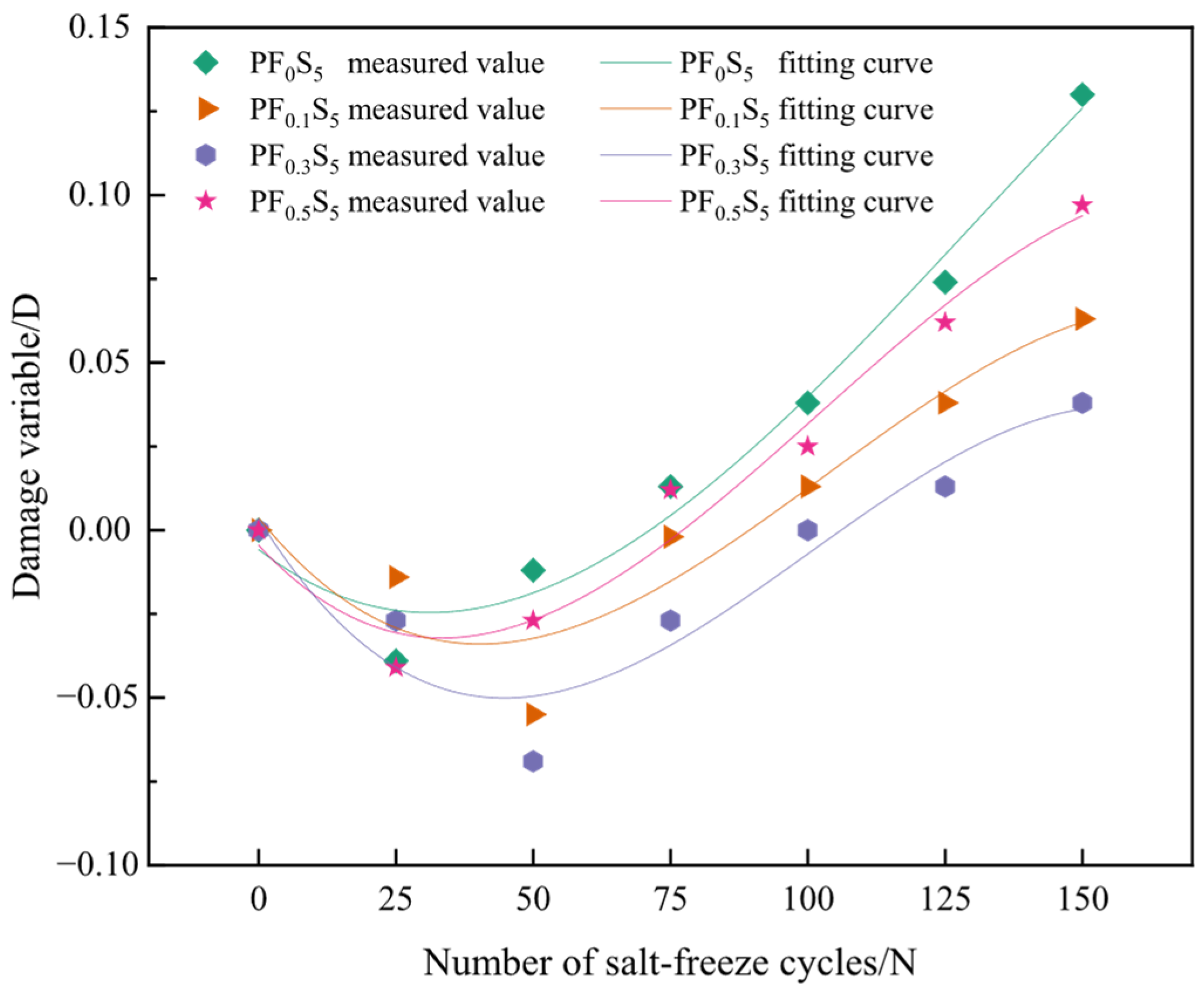

4. Damage Evolution Model for PVA Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Under Salt-Freeze Conditions

5. Conclusions

- (1)

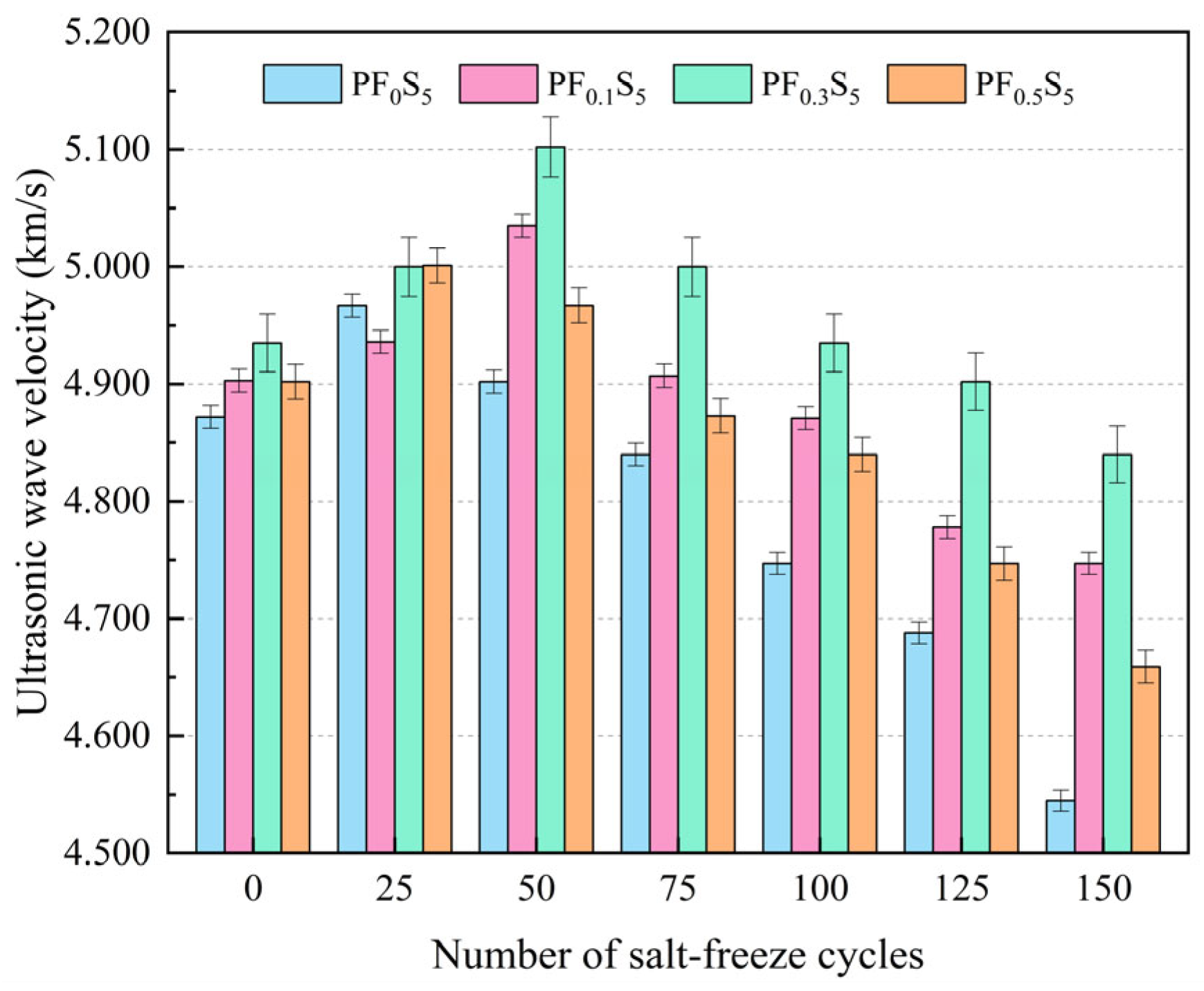

- Under the coupled salt-freeze action, the mass, relative dynamic elastic modulus, and cube compressive strength of all mixtures exhibited an initial increase followed by a decrease with increasing cycles, whereas the splitting tensile strength decreased monotonically. The incorporation of PVA fibers effectively mitigated this degradation, with the 0.3% fiber dose demonstrating optimal salt-freeze resistance, providing a direct and practical benchmark for material design in such aggressive environments.

- (2)

- Comparative SEM micrographs revealed a denser microstructure with fewer visible pores and microcracks in PVA fiber concrete than in plain concrete. This microstructural improvement, consistent with the pore-refining capability reported for PVA fibers [18], is attributed to the strong fiber–matrix bonding and the physical filling effect of fibers. After exposure, the plain concrete developed extensive porosity and interconnected cracks, whereas the fiber-reinforced concrete showed restrained crack propagation without forming continuous damage paths, confirming the effective crack-bridging role of fibers. These mechanisms collectively explain the enhanced crack resistance and toughness observed at the macro scale.

- (3)

- XRD diffraction analysis indicated that with increasing salt-freeze cycles, the content of erosion products (ettringite and gypsum) in concrete gradually rose, with the gypsum proportion showing significant enhancement alongside increasing sulfate ion concentration, while portlandite content progressively decreased. Comparative analysis revealed that PF0.3S5 specimens generally exhibited lower formation of erosion products than PF0S5 specimens, demonstrating superior salt-freeze resistance. This suppression of deleterious chemical reactions, alongside the physical crack-bridging, constitutes the dual micro-mechanism responsible for the improved long-term durability of fiber-reinforced concrete under coupled attack.

- (4)

- A damage evolution model, established based on the loss rate of relative dynamic elastic modulus, demonstrated a high-accuracy cubic relationship between damage degree D and salt-freeze cycles N (R2 > 0.88). This empirical model offers a valuable quantitative tool for predicting the damage progression and assessing the residual service life of PVA fiber-reinforced concrete in similar service conditions.

- (5)

- In summary, within the existing research framework on sulfate-freeze–thaw coupled damage [7], this study further clarified the improvement effect and microscopic mechanisms of PVA fibers on the salt-freeze resistance of concrete. The results not only validate the effectiveness of fibers in inhibiting the generation of erosion products and delaying the propagation of microcracks but also provide experimental evidence and model support for the fiber-reinforced design of concrete structures in severely cold and high-salinity regions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kanwal, H.; Amin, N.; Azhar, N.; Rizwan, M.; Javed, K.; Asim, M.; Hussain, S.; Ahsan, M.; Salman, M. Effect of Natural Raw Fibers on Mechanical Properties of Fiber Reinforced Concrete: A Step Towards Sustainability. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2024, 14, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Q.H.; Li, Q.; Cao, Z.Y.; Tian, W.Y. The Deterioration Law of Recycled Concrete under the Combined Effects of Freeze-Thaw and Sulfate Attack. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 200, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.K.; Monteiro, P.J.M. Concrete: Microstructure, Properties, and Materials, 3rd ed.; China Electric Power Press: Beijing, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, T.C. A Working Hypothesis for Further Studies of Frost Resistance of Concrete. J. Am. Concr. Inst. 1945, 16, 245–272. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, T.C.; Helmuth, R.A. Theory of Volume Change in Hardened Portland Cement Paste during Freezing. Highw. Res. Board Proc. 1953, 32, 285–297. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B.X.; Pan, J.J.; Fang, R.C.; Wang, Q. Damage Model of Concrete Subjected to Coupling Chemical Attacks and Freeze-Thaw Cycles in Saline Soil Area. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 242, 118205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Z.Z.; Chen, G. Damage evolution law of concrete under sulfate erosion and freeze-thaw cycles. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. Nat. Sci. Ed. 2023, 51, 134–141. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.J.; So, C.S.; Chen, W.S.; Htet, P.M.; Hao, H. Mechanical Properties of Basalt Macro Fibre Reinforced Geopolymer Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 136974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.D.; Zhang, D.M.; Zhang, X.; Huang, Z.K.; Xie, X.C. Experimental and Mesoscale Numerical Investigation on Tensile Properties of Steel Fibre-Reinforced Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 458, 139601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.H.; Chen, Z.X.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Chen, P.; Zhang, Y.Z. Mechanical Properties and Flexural Toughness Evaluation Method of Mono/Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Ultra-High Performance Seawater Sea Sand Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 469, 139861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, W.G.; Yang, Z.L.; Yu, L.L. Study on Frost Resistance of the Carbon-Fibre-Reinforced Concrete. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.J.; Cao, Z.L.; Li, Y.; Shi, Q. The Influence of Fiber on Salt Frost Resistance of Hydraulic Face Slab Concrete. Struct. Concr. 2022, 24, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.L.; Wang, H.L.; Xue, H.J.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Wei, L.S. Study on Damage Deterioration Mechanism and Service Life Prediction of Hybrid Fibre Concrete under Different Salt Freezing Conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 435, 136688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jia, B.; Huang, H.; Mou, Y.L. Experimental Study on Basic Mechanical Properties of Basalt Fiber Reinforced Concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abed, M.A.; Fořt, J.; Naoulo, A.; Essa, A. Influence of Polypropylene and Steel Fibers on the Performance and Crack Repair of Self-Compacting Concrete. Materials 2021, 14, 5506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Yu, X.B.; Liang, Y.T.; Gong, X.L.; Du, Q.Y. Multi-scale Deterioration and Microstructure of Polypropylene Fiber Concrete by Salt Freezing. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e01762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.F.; Qiao, H.X.; Fu, Y.; Wang, X.K. Freeze-thaw test and numerical analysis of basalt fiber reinforced concrete in western saline soil regions. J. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 52, 3431–3443. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Hu, C.L.; Wang, F.Z.; Hu, S.G. Improving the Interfacial Properties of PVA Fiber and Cementitious Composite: Design and Characterization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 409, 133869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.G.; Wang, X.Z.; Li, X.F.; Su, L.; Tian, J.B.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.H. Research on the Mechanical Properties and Pore Structure Deterioration of Basalt-Polyvinyl Alcohol Hybrid Fiber Concrete under the Coupling Effects of Sulfate Attack and Freeze-Thaw Cycles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 473, 140949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.M.; Zhao, N.; Wang, S.L.; Quan, X.Y.; Liu, K.N.; Xu, J.; Wang, Z.Y.; Ying, H.H.; Liu, B. Mechanical and Durability Performance of Polyvinyl Alcohol Fiber Hybrid Geopolymer-Portland Cement Concrete under Freeze–Thaw Cycles. Bol. Soc. Esp. Ceram. Vidr. 2024, 63, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, T.; Yang, Y.Q.; Zhou, Y.F. Effect of PVA Fiber on the Dynamic and Static Mechanical Properties of Concrete under Freeze-Thaw Cycles at Extremely Low Temperature (−70 °C). J. Wuhan Univ. Technol.-Mater. Sci. Ed. 2023, 38, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Xie, X.S.; Chen, J.; Jin, W.L. Behavior of PVA Fiber Concrete under Freezing and Thawing Cycles. Indian J. Eng. Mater. Sci. 2015, 22, 693–700. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.C.; Chen, J.; Qiao, H.X. Performance Degradation of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete under Freeze–Thaw Cycles and Its Resistance to Chloride Ion Penetration. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 04022185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.L.; Li, D.S.; Zhang, Z.K. Bond Durability of GFRP and BFRP Bars Embedded in PVA Fiber–Reinforced Seawater and Sea-Sand Concrete under Seawater Freeze–Thaw Cycles. J. Compos. Constr. 2024, 28, 04024045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahat, H.H.; Tran, T.Q.; Banik, D.; Brand, A.S. Effects of Polyvinyl Alcohol Fibers and Curing Duration on Chloride Ingress in Concrete during Freeze-Thaw Cycles. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 108, 112930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JGJ 55-2000; Specification for Mix Proportion Design of Ordinary Concrete. Ministry of Construction of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2000.

- GB/T 50082-2024; Standard for Test Methods of Long-Term Performance and Durability of Ordinary Concrete. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2024.

- Lu, C.G. Durability Test Research and Life Prediction and Evaluation of Concrete Structural Materials in the Saline Environment of Northwest China. Ph.D. Thesis, Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, L.D. Experimental Study on the Durability of Concrete Under the Combined Action of Sulfate Erosion and Freeze-Thaw Cycle. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Architecture and Technology, Xi’an, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 50081-2019; Standard for Test Methods of Concrete Physical and Mechanical Properties. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Ikumi, T.; Cavalaro, S.H.; Segura, I.; Aguado, A. Alternative Methodology to Consider Damage and Expansions in External Sulfate Attack Modeling. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 63, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, A.; Komar, A.; Sanchez, L.F.; Boyd, A.J. Global Assessment of Concrete Specimens Subjected to Freeze-Thaw Damage. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2022, 133, 104716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Length (mm) | Diameter (μm) | Density (g/cm3) | Elongation at Break (%) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Modulus of Elasticity (GPa) | Moisture Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 15.3 | 1.29 | 7 | 1830 | 40 | <0.1 |

| Test-Piece Number | Water (kg/m3) | Cement (kg/m3) | Medium Sand (kg/m3) | Spall (kg/m3) | Fly Ash (kg/m3) | Water-Reducing Agent (kg/m3) | PVA Fiber Volume Content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PF0S5 | 187 | 356 | 707 | 1060 | 90 | 0.223 | 0 |

| PF0.1S5 | 187 | 356 | 707 | 1060 | 90 | 0.268 | 0.1 |

| PF0.3S5 | 187 | 356 | 707 | 1060 | 90 | 0.357 | 0.3 |

| PF0.5S5 | 187 | 356 | 707 | 1060 | 90 | 0.446 | 0.5 |

| Specimen Number | Salt-Freeze Cycles N | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | 125 | 150 | |

| PF0S5 | 0 | −0.039 | −0.012 | 0.013 | 0.038 | 0.074 | 0.130 |

| PF0.1S5 | 0 | −0.014 | −0.055 | −0.002 | 0.013 | 0.038 | 0.063 |

| PF0.3S5 | 0 | −0.027 | −0.069 | −0.027 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 0.038 |

| PF0.5S5 | 0 | −0.041 | −0.027 | 0.012 | 0.025 | 0.062 | 0.097 |

| Specimen Number | Fitting Equation |

|---|---|

| PF0S5 | = −5.86667 × 10−8 + 2.31048 × 10−5 − 0.00127 − 0.00576 |

| PF0.1S5 | = −1.01333 × 10−7 + 3.13524 × 10−5 − 0.00203 + 0.00369 |

| PF0.3S5 | = −1.26222 × 10−7 + 3.80190 × 10−5 − 0.00264 + 0.00343 |

| PF0.5S5 | = −1.03111 × 10−7 + 3.16381 × 10−5 − 0.00177 − 0.00450 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wu, H.; Shen, C.; Lv, C.; Sun, Y.; Qu, S.; Zhou, X. Durability and Microstructural Evolution of PVA-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Under Coupled Sulfate Attack and Freeze–Thaw Conditions. Materials 2026, 19, 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010098

Wu H, Shen C, Lv C, Sun Y, Qu S, Zhou X. Durability and Microstructural Evolution of PVA-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Under Coupled Sulfate Attack and Freeze–Thaw Conditions. Materials. 2026; 19(1):98. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010098

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Hairong, Changhao Shen, Chenjie Lv, Yuzhou Sun, Songzhao Qu, and Xiangming Zhou. 2026. "Durability and Microstructural Evolution of PVA-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Under Coupled Sulfate Attack and Freeze–Thaw Conditions" Materials 19, no. 1: 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010098

APA StyleWu, H., Shen, C., Lv, C., Sun, Y., Qu, S., & Zhou, X. (2026). Durability and Microstructural Evolution of PVA-Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Under Coupled Sulfate Attack and Freeze–Thaw Conditions. Materials, 19(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010098