Vibration Behaviour of Topologically Optimised Sacrificial Geometries for Precision Machining of Thin-Walled Components

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Designs, Simulations, and Optimisations

2.2. Laser Powder Bed Fusion and Heat Treatments

2.3. Tap Testing

2.4. Machining and Surface Quality Measurements

3. Results and Discussions

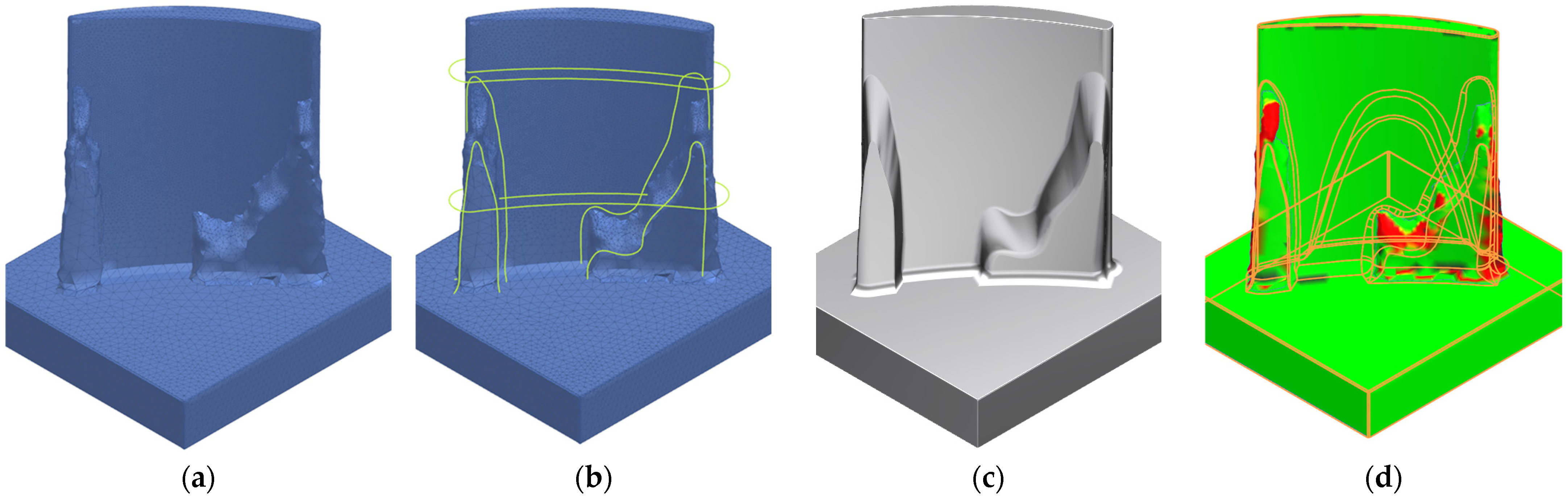

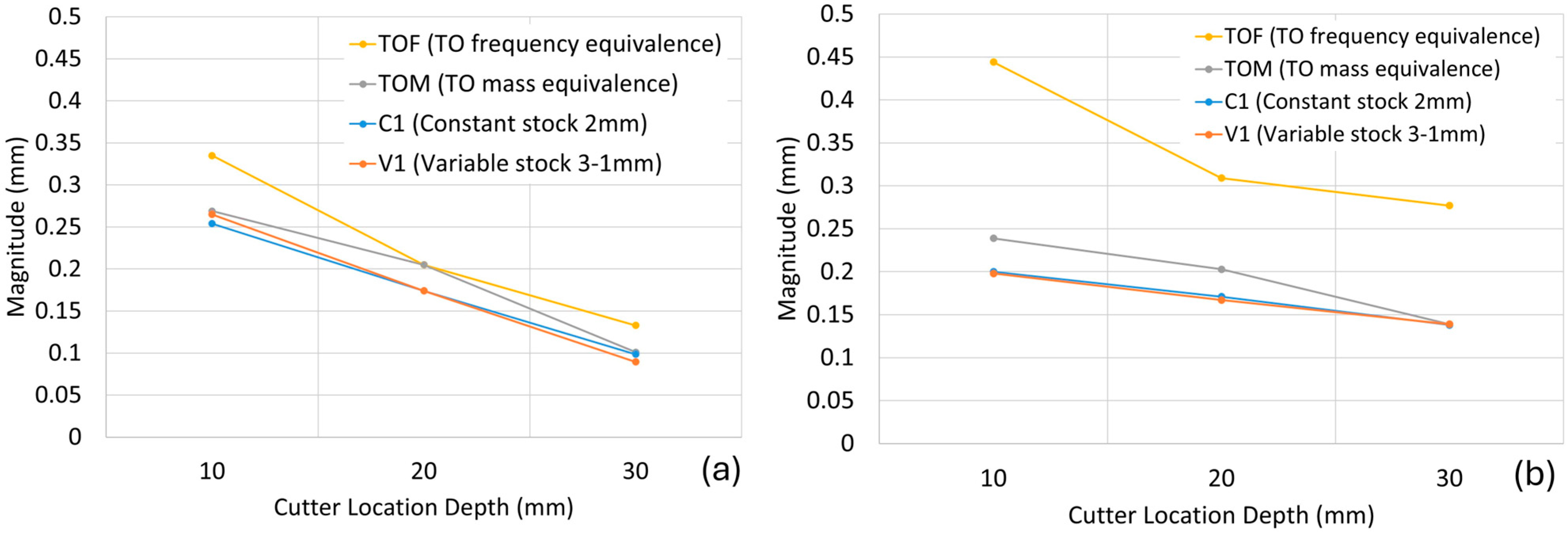

3.1. Simulation and Optimisation Results

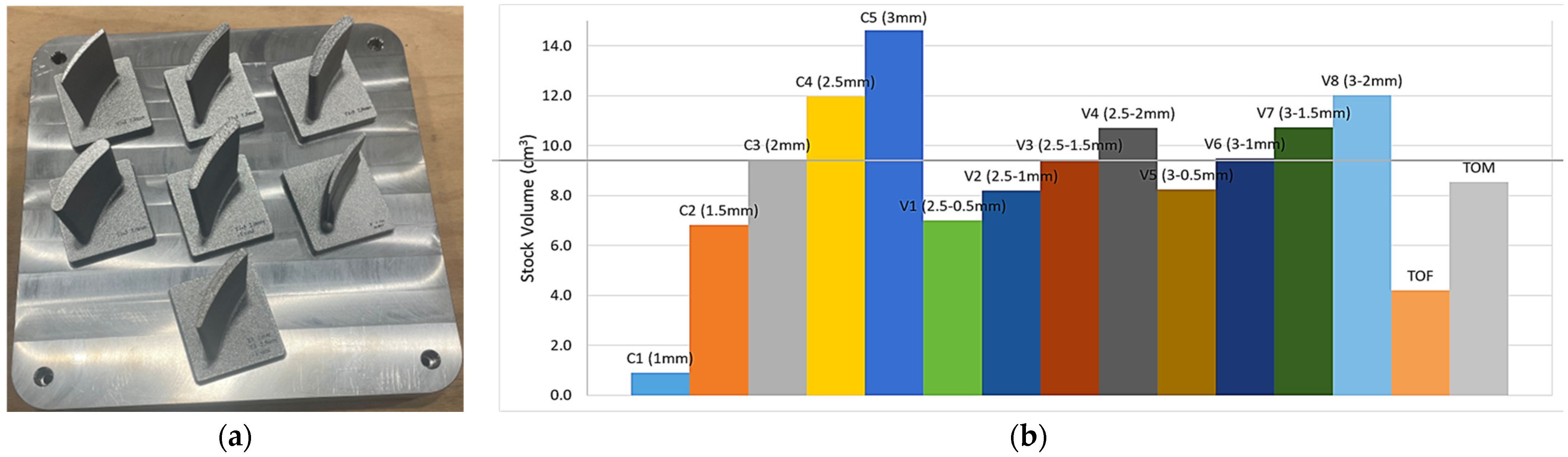

3.2. Blade Production and Material Consumption Comparisons

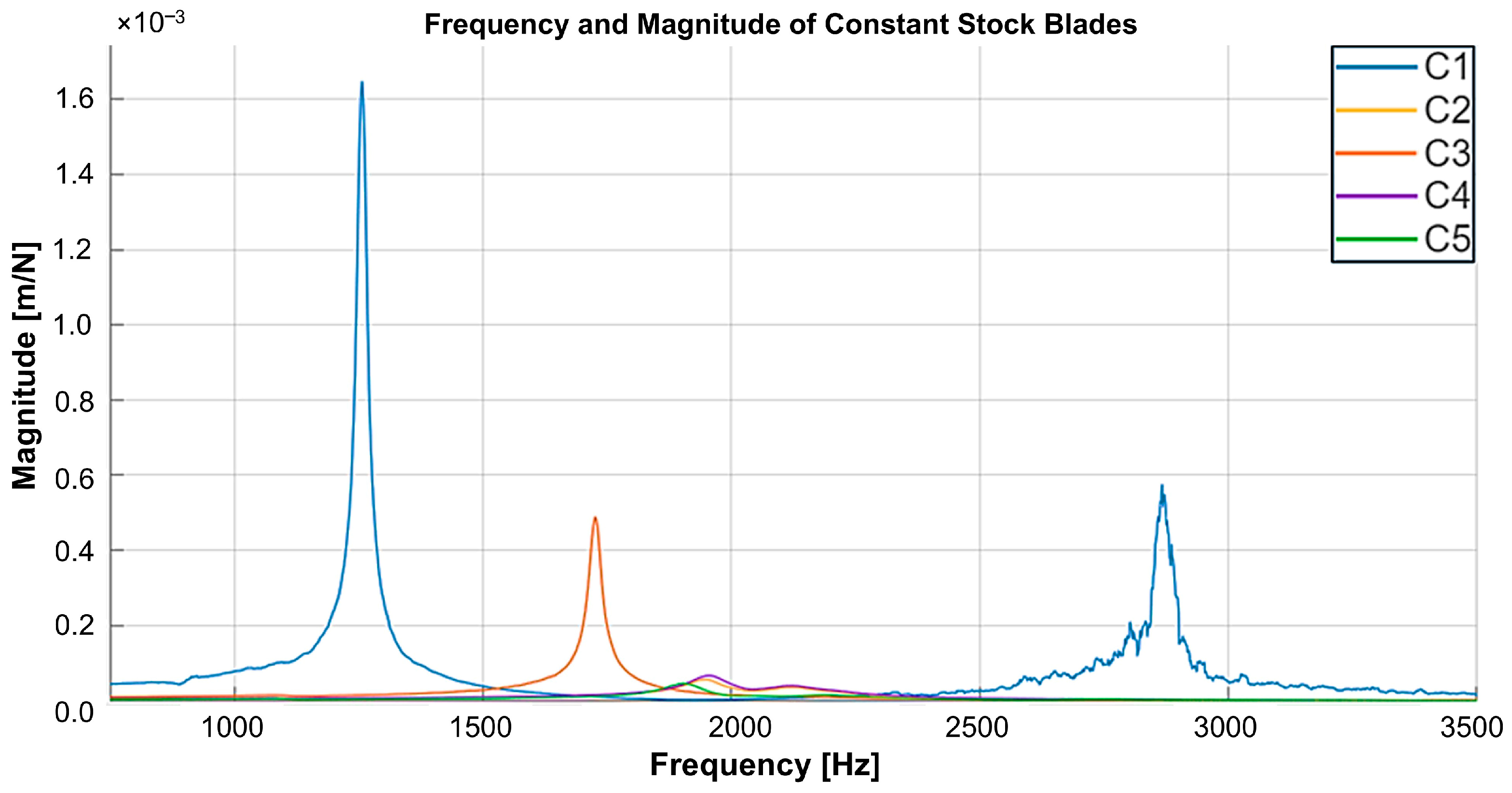

3.3. Vibration Behaviour of Blades Prior to Machining

3.4. Machining Observations and Surface Conditions

4. Conclusions

- Prior to machining, tap testing was conducted to evaluate the modal behaviour of the blades. The findings demonstrated that optimised geometries can deliver superior modal performance while maintaining the same stock volume to be removed.

- In situ changes in modal characteristics were more pronounced in optimised blades due to variability in material removal rates, radial depth of cut, chip thickness, and cutting forces, compared with constant or variable stock designs.

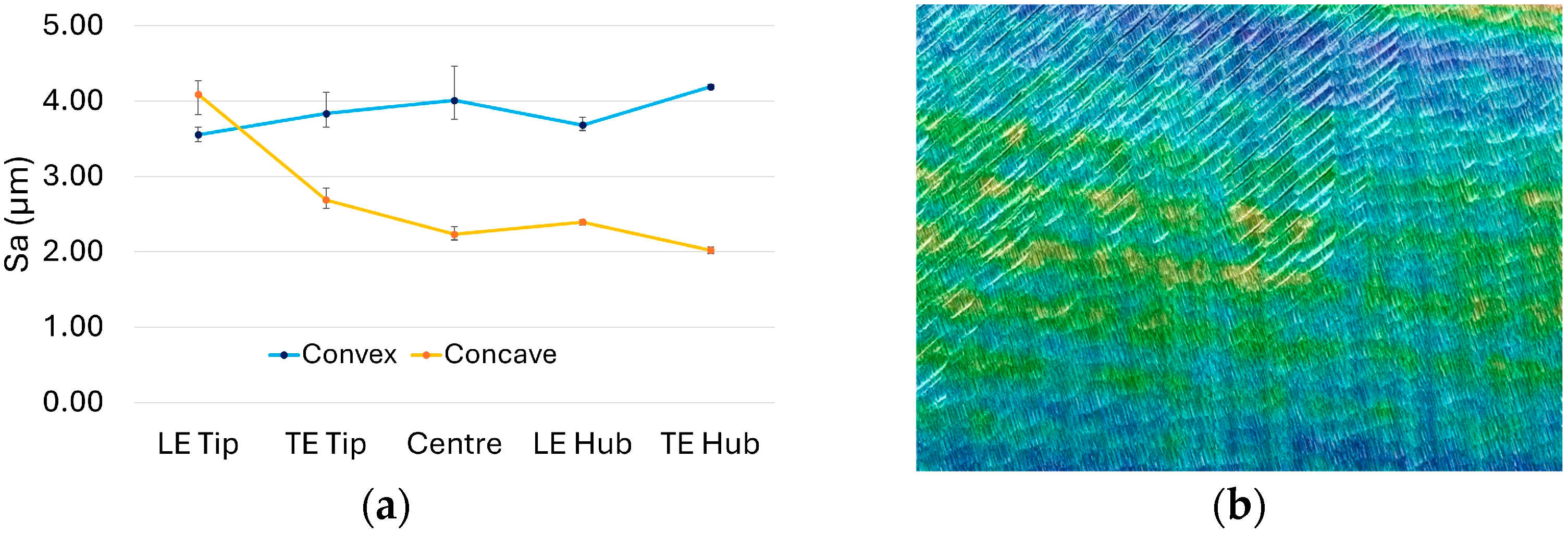

- Surface roughness was consistently 10–20% higher on convex surfaces than concave surfaces across all blade configurations, primarily because the outward curvature increases cutting forces and tool deflection, as addressed in the literature as contributors to rougher finishes on convex geometries.

- Constant stock blades exhibited a decreasing surface roughness trend from hub to tip; variable stock blades maintained relatively uniform finishes, while optimised blades showed significant surface roughness fluctuations, likely due to uneven stock distribution and process instability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ge, J.; Pillay, S.; Ning, H. Post-Process Treatments for Additive-Manufactured Metallic Structures: A Comprehensive Review. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2023, 32, 7073–7122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçak, N.; Çiçek, A.; Aslantas, K. Machinability of 3D Printed Metallic Materials Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting and Electron Beam Melting: A Review. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 80, 414–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsan, A.U.H.; Liu, Z.; Padhy, G.K. A Review on the Progress towards Improvement in Surface Integrity of Inconel 718 under High Pressure and Flood Cooling Conditions. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 91, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draz, U.; Hussain, S. Machining-Induced Geometric Errors in Thin-Walled Parts—A Review of Mitigation Strategies and Development of Application Guidelines. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 136, 4175–4214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Ding, W.; Shan, Z.; Wang, J.; Yao, C.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, J.; Xiao, S.; Ding, Y.; Tang, X.; et al. Collaborative Manufacturing Technologies of Structure Shape and Surface Integrity for Complex Thin-Walled Components of Aero-Engine: Status, Challenge and Tendency. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Song, Q.; Jin, P.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Ma, H. Chatter Suppression Techniques in Milling Processes: A State of the Art Review. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2024, 37, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Long, X. Chatter Suppression for Milling of Thin-Walled Workpieces Based on Active Modal Control. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 84, 1042–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.K.A.; Nejatpour, M.; Yagci Acar, H.; Lazoglu, I. A New Magnetorheological Damper for Chatter Stability of Boring Tools. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2021, 289, 116931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ma, H.; Sun, Y.; Song, Q.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, Z. An Interpretable Anti-Noise Convolutional Neural Network for Online Chatter Detection in Thin-Walled Parts Milling. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 206, 110885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Li, T.; Bo, Q.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y. Fixturing Technology and System for Thin-Walled Parts Machining: A Review. Front. Mech. Eng. 2022, 17, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, X.-B.; Wan, M.; Zhang, W.-H.; Yang, Y. Chatter Analysis and Mitigation of Milling of the Pocket-Shaped Thin-Walled Workpieces with Viscous Fluid. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 194, 106214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, C.; Han, L.; Wang, S.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y. The Influence of Ice-Based Fixture on Suppressing Machining-Induced Deformation of Cantilever Thin-Walled Parts: A Novel and Green Fixture. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 117, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolluru, K.; Axinte, D.; Becker, A. A Solution for Minimising Vibrations in Milling of Thin Walled Casings by Applying Dampers to Workpiece Surface. CIRP Ann. 2013, 62, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Wilhelm, R.; Dutterer, B.; Cherukuri, H.; Goel, G. Sacrificial Structure Preforms for Thin Part Machining. CIRP Ann. 2012, 61, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, D.; Saldana, C.; Kurfess, T.; Nycz, A. Implementation of Sacrificial Support Structures for Hybrid Manufacturing of Thin Walls. JMMP 2022, 6, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunc, L.T.; Zatarain, M. Stability Optimal Selection of Stock Shape and Tool Axis in Finishing of Thin-Wall Parts. CIRP Ann. 2019, 68, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petráček, P.; Falta, J.; Stejskal, M.; Šimůnek, A.; Kupka, P.; Sulitka, M. Chatter-Free Milling Strategy of a Slender Blisk Blade via Stock Distribution Optimization and Continuous Spindle Speed Change. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 124, 1273–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cai, Y.; Xi, X.; Wang, H. Non-Uniform Machining Allowance Planning Method of Thin-Walled Parts Based on the Workpiece Deformation Constraint. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 124, 2185–2198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, B.; Altintas, Y. Optimal Stock Removal to Reduce Chatter and Deflection Errors for Five-Axis Ball-End Milling of Thin-Walled Blades. CIRP Ann. 2024, 73, 293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunc, L.T.; Gulmez, D.A. Tool Path Strategies for Efficient Milling of Thin-Wall Features. JMMP 2024, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kienast, P.; Tunç, L.T.; Koca, R.; Ölgü, O.; Ganser, P.; Bergs, T. Improving Dynamic Process Stability in Finishing of Thin-Walled Workpieces by Optimal Selection of Stock Shape. Procedia CIRP 2024, 126, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Liu, X.; Zhang, S.; Lin, Y.; Tan, J. Diameter-Adjustable Mandrel for Thin-Wall Tube Bending and Its Domain Knowledge-Integrated Optimization Design Framework. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, J.D.; Heiser, W.H.; Pratt, D.T. Aircraft Engine Design. In AIAA Education Series, 2nd ed.; American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, USA, 2004; ISBN 9781563475382. [Google Scholar]

- Rolls-Royce, Ltd. The Jet Engine; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 2015; ISBN 9781523111145. [Google Scholar]

- Depboylu, F.N.; Yasa, E.; Poyraz, O.; Korkusuz, F. Thin-Walled Commercially Pure Titanium Structures: Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process Parameter Optimization. Machines 2023, 11, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renishaw. RenAM 500 series material data sheet. In Titanium Ti6Al4V (Grade 23), Properties of Additively Manufactured Parts; Layer thickness 60 µm; Renishaw: Wotton-under-Edge, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhu, H.; Hu, Z.; Nagarajan, B.; Guo, L.; Zeng, X. Study of Residual Stress in Selective Laser Melting of Ti6Al4V. Mater. Des. 2020, 193, 108846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, Ó.; Silva, F.J.G.; Ferreira, L.P.; Atzeni, E. A Review of Heat Treatments on Improving the Quality and Residual Stresses of the Ti–6Al–4V Parts Produced by Additive Manufacturing. Metals 2020, 10, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAE Standard AMS2750; PYROMETRY. AMS B Finishes Processes and Fluids Committee. SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 1980. [CrossRef]

- Budak, E.; Tunç, L.T.; Alan, S.; Özgüven, H.N. Prediction of Workpiece Dynamics and Its Effects on Chatter Stability in Milling. CIRP Ann. 2012, 61, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurpiel, S.; Zagórski, K.; Cieślik, J.; Skrzypkowski, K. Investigation of Selected Surface Topography Parameters and Deformation during Milling of Vertical Thin-Walled Structures from Titanium Alloy Ti6Al4V. Materials 2023, 16, 3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Yue, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Liang, S.Y.; Nan, Y. Modeling of Convex Surface Topography in Milling Process. Metals 2020, 10, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.Y.; Liu, Z.; Cai, Y.; Wang, B.; Li, G. Optimisation of Planning Parameters for Machining Blade Electrode Micro-Fillet with Scallop Height Modelling. Micromachines 2021, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Matras, A.; Zębala, W.; Machno, M. Research and Method of Roughness Prediction of a Curvilinear Surface after Titanium Alloy Turning. Materials 2019, 12, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constant | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | |||

| Tip stock (mm) | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | |||

| Hub stock (mm) | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | |||

| Variable | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | V5 | V6 | V7 | V8 |

| Tip stock (mm) | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 2 |

| Hub stock (mm) | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Property | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Density | kg/m3 | 4391 |

| Young’s Modulus | Pa | 1.15 × 1011 |

| Poisson’s Ratio | - | 0.34 |

| Bulk Modulus | Pa | 1.97 × 1011 |

| Shear Modulus | Pa | 4.29 × 1010 |

| Element | Al | Y | V | Ti | O | N | H | Fe | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (%) | 6.02 | <0.001 | 3.93 | Bal. | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.0010 | 0.19 | <0.01 |

| Scan Strategy | Parameter | Unit | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volumetric Energy Density (VED) | J/mm3 | 37 |

| Layer thickness | µm | 60 | |

| Laser power | W | 320 | |

| Scan Speed | mm/s | 1500 | |

| Hatch distance | µm | 95 |

| Toolpath | Tool | Operation | Axial Depth of Cut (mm) | Radial Depth of Cut (mm) | Surface Speed (m/min) | Feed Rate (mm/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bull nose—10 mm | Rough | 0.25 | 1 | 85 | 0.03 |

| Ball nose—10 mm | Semi-finish | 0.25 | 0.5 | 85 | 0.035 | |

| Tapered ball nose—3 mm | Finish | 0.15 | 0.5 | 60 | 0.013 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Yasa, E.; Poyraz, O.; Parson, F.P.C.; Molyneux, A.; Baxter, M.E.; Hughes, J. Vibration Behaviour of Topologically Optimised Sacrificial Geometries for Precision Machining of Thin-Walled Components. Materials 2026, 19, 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010070

Yasa E, Poyraz O, Parson FPC, Molyneux A, Baxter ME, Hughes J. Vibration Behaviour of Topologically Optimised Sacrificial Geometries for Precision Machining of Thin-Walled Components. Materials. 2026; 19(1):70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010070

Chicago/Turabian StyleYasa, Evren, Ozgur Poyraz, Finlay P. C. Parson, Anthony Molyneux, Marie E. Baxter, and James Hughes. 2026. "Vibration Behaviour of Topologically Optimised Sacrificial Geometries for Precision Machining of Thin-Walled Components" Materials 19, no. 1: 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010070

APA StyleYasa, E., Poyraz, O., Parson, F. P. C., Molyneux, A., Baxter, M. E., & Hughes, J. (2026). Vibration Behaviour of Topologically Optimised Sacrificial Geometries for Precision Machining of Thin-Walled Components. Materials, 19(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010070