Study on the Application of Machine Learning of Melt Pool Geometries in Silicon Steel Fabricated by Powder Bed Fusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Framework and Data Preparation

2.2. Sample Fabrication and Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Model Development

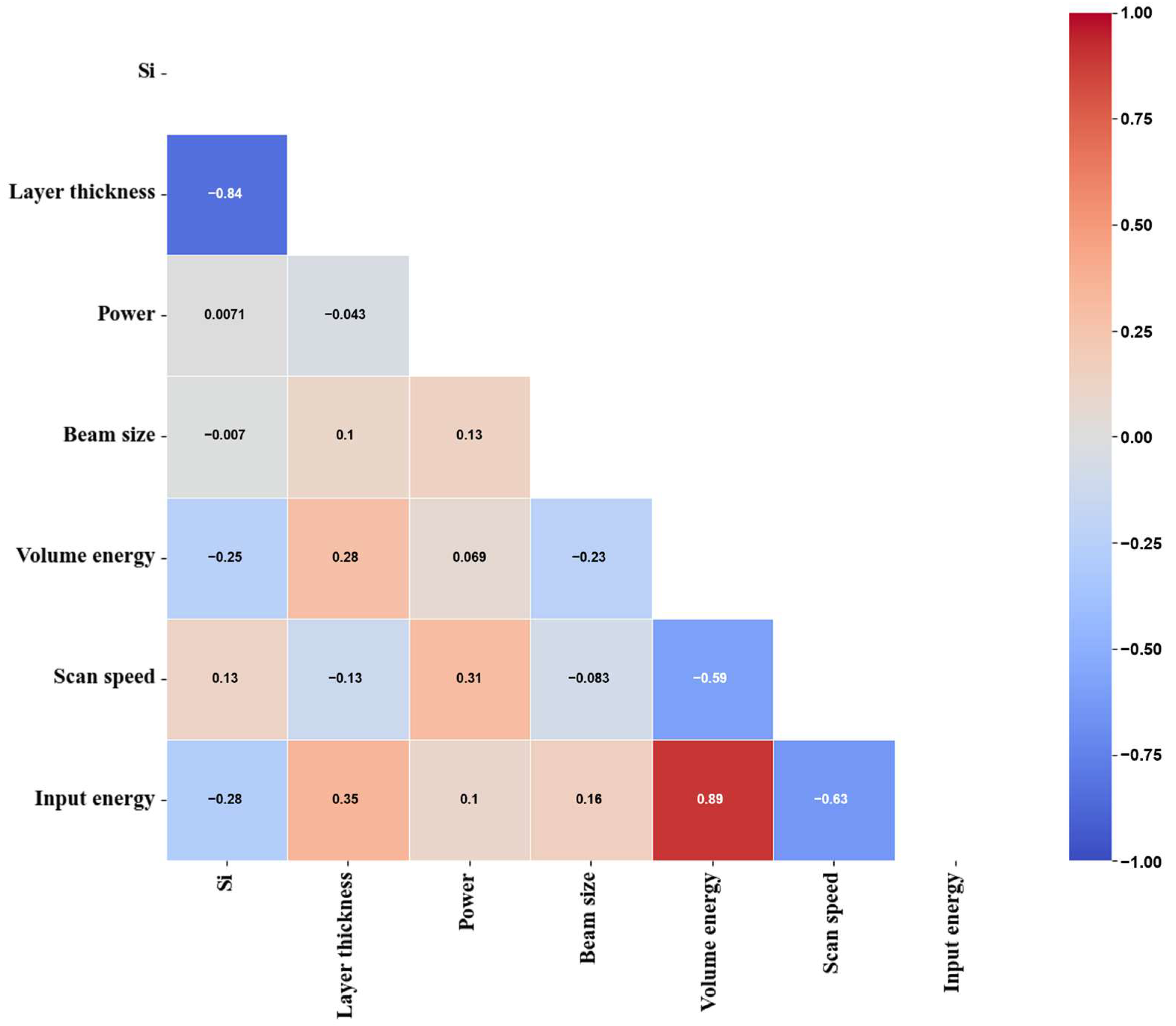

3.2. Feature Importance and SHAP Analysis

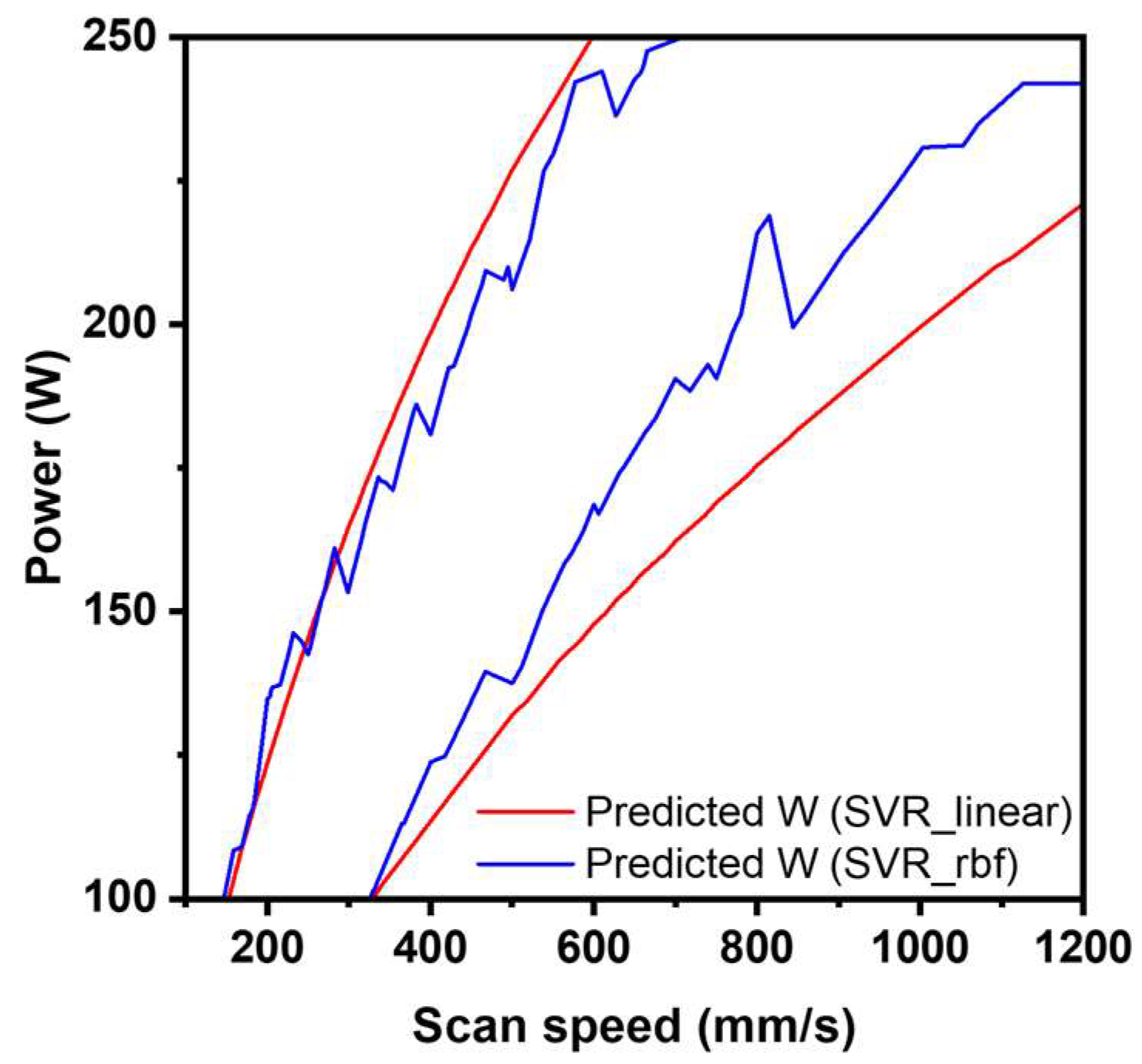

3.3. Reverse Engineering and Process Map Derivation

3.4. Experimental Validation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- O’Handley, R.C. Modern Magnetic Materials: Principles and Applications; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y. Room-Temperature Ferromagnetism of Graphene. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibaldi, M.; Gerada, C.; Ashcroft, I.; Hague, R.; Morvan, H. The Impact of Additive Manufacturing on the Development of Electrical Machines for MEA Applications: A Feasibility Study. In Proceedings of the MEA2015 More Electric Aircraft, Toulouse, France, 4–5 February 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lamichhane, T.N.; Sethuraman, L.; Dalagan, A.; Wang, H.; Keller, J.; Paranthaman, M.P. Additive Manufacturing of Soft Magnets for Electrical Machines—A Review. Mater. Today Phys. 2020, 15, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertan, H.B.; Üçtug, M.Y.; Colyer, R.; Consoli, A. Modern Electrical Drives; Springer Science & Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 369. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Zhao, C.; Qu, M.; Xiong, L.; Escano, L.I.; Hojjatzadeh, S.M.H.; Parab, N.D.; Fezzaa, K.; Everhart, W.; Sun, T.; et al. In-Situ Characterization and Quantification of Melt Pool Variation under Constant Input Energy Density in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing Process. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 28, 600–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Fezzaa, K.; Cunningham, R.W.; Wen, H.; De Carlo, F.; Chen, L.; Rollett, A.D.; Sun, T. Real-Time Monitoring of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process Using High-Speed X-Ray Imaging and Diffraction. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, S.A.; Anderson, A.T.; Rubenchik, A.; King, W.E. Laser Powder-Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing: Physics of Complex Melt Flow and Formation Mechanisms of Pores, Spatter, and Denudation Zones. Acta Mater. 2016, 108, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvish, K.; Chen, Z.W.; Pasang, T. Reducing Lack of Fusion during Selective Laser Melting of CoCrMo Alloy: Effect of Laser Power on Geometrical Features of Tracks. Mater. Des. 2016, 112, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, W.E.; Barth, H.D.; Castillo, V.M.; Gallegos, G.F.; Gibbs, J.W.; Hahn, D.E.; Kamath, C.; Rubenchik, A.M. Observation of Keyhole-Mode Laser Melting in Laser Powder-Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2014, 214, 2915–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Tan, X.; Tor, S.B.; Yeong, W.Y. Selective Laser Melting of Stainless Steel 316L with Low Porosity and High Build Rates. Mater. Des 2016, 104, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Tan, X.; Liu, E.; Tor, S.B. Process Parameter Optimization and Mechanical Properties for Additively Manufactured Stainless Steel 316L Parts by Selective Electron Beam Melting. Mater. Des. 2018, 147, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olakanmi, E.O.; Cochrane, R.F.; Dalgarno, K.W. Densification Mechanism and Microstructural Evolution in Selective Laser Sintering of Al–12Si Powders. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2011, 211, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilania, G.; Wang, C.; Jiang, X.; Rajasekaran, S.; Ramprasad, R. Accelerating Materials Property Predictions Using Machine Learning. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, L.; Agrawal, A.; Choudhary, A.; Wolverton, C. A General-Purpose Machine Learning Framework for Predicting Properties of Inorganic Materials. npj Comput. Mater 2016, 2, 16028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-L.; Adachi, Y. Property Prediction and Properties-to-Microstructure Inverse Analysis of Steels by a Machine-Learning Approach. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 744, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Hu, X. Recurrent Convolutional Neural Network for Object Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 3367–3375. [Google Scholar]

- Scime, L.; Beuth, J. Using Machine Learning to Identify In-Situ Melt Pool Signatures Indicative of Flaw Formation in a Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing Process. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 25, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Guss, G.M.; Wilson, A.C.; Hau-Riege, S.P.; DePond, P.J.; McMains, S.; Matthews, M.J.; Giera, B. Machine-Learning-Based Monitoring of Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2018, 3, 1800136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, G.; Khairallah, S.; Matthews, M.; King, W.E.; Elwany, A. Gaussian Process-Based Surrogate Modeling Framework for Process Planning in Laser Powder-Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing of 316L Stainless Steel. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 94, 3591–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babyak, M.A. What You See May Not Be What You Get: A Brief, Nontechnical Introduction to Overfitting in Regression-Type Models. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natekin, A.; Knoll, A. Gradient Boosting Machines, a Tutorial. Front. Neurorobot. 2013, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mankar, A.; Kharade, K.; Mankar, A.D.; Bhoite, S.D.; Kharade, K.G.; Raskar, K.A. METAANALYSIS OF OVERFITTING OF DECISION TREES. J. Nonlinear Anal. Optim. Theory Appl. 2024, 15, 30–36. [Google Scholar]

- Vapnik, V. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory; Springer Science & Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-Vector Networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, V.D.A. Advanced Support Vector Machines and Kernel Methods. Neurocomputing 2003, 55, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smola, A.J.; Schölkopf, B.; Schölkopf, S. A Tutorial on Support Vector Regression*; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Aoyagi, K.; Wang, H.; Sudo, H.; Chiba, A. Simple Method to Construct Process Maps for Additive Manufacturing Using a Support Vector Machine. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 27, 353–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, P.; Ogoke, F.; Kao, N.Y.; Meidani, K.; Yeh, C.Y.; Lee, W.; Barati Farimani, A. MeltpoolNet: Melt Pool Characteristic Prediction in Metal Additive Manufacturing Using Machine Learning. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 55, 102817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuehne, M.; Bartsch, K.; Bossen, B.; Emmelmann, C. Predicting Melt Track Geometry and Part Density in Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Metals Using Machine Learning. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 8, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Erion, G.; Chen, H.; DeGrave, A.; Prutkin, J.M.; Nair, B.; Katz, R.; Himmelfarb, J.; Bansal, N.; Lee, S.-I. From Local Explanations to Global Understanding with Explainable AI for Trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2020, 2, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Han, J.; Yu, H.; Yin, J.; Gao, M.; Wang, Z.; Zeng, X. Role of Molten Pool Mode on Formability, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Selective Laser Melted Ti-6Al-4V Alloy. Mater. Des. 2016, 110, 558–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Khairallah, S.A.; Rubenchik, A.M.; Crumb, M.F.; Guss, G.; Belak, J.; Matthews, M.J. Energy Coupling Mechanisms and Scaling Behavior Associated with Laser Powder Bed Fusion Additive Manufacturing. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2019, 21, 1900185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Liu, Y.; Shi, X.; Hou, Y.; Wang, P.; Song, G. Beam Diameter Dependence of Performance in Thick-Layer and High-Power Selective Laser Melting of Ti-6Al-4V. Materials 2018, 11, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siao, Y.H.; Wen, C. Da Influence of Process Parameters on Heat Transfer of Molten Pool for Selective Laser Melting. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2021, 193, 110388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.S.; Kim, S.H.; Park, G.W.; Jeon, J.B.; Kim, D.; Choi, Y.S.; Shin, S. Effects of Laser-Beam Diameter on Melt Pool Characteristics and Grain Formation in Fe-3.4 Wt%Si Alloy Made by Powder Bed Fusion. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 2938–2950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunenthiram, V.; Peyre, P.; Schneider, M.; Dal, M.; Coste, F.; Fabbro, R. Analysis of Laser–Melt Pool–Powder Bed Interaction during the Selective Laser Melting of a Stainless Steel. J. Laser Appl. 2017, 29, 022303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, J.; Lei, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Qin, X.; Tian, Z. Effect of Process Parameters on Formability and Surface Quality of Selective Laser Melted Al-Zn-Sc-Zr Alloy from Single Track to Block Specimen. Opt. Laser Technol. 2019, 118, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadroitsev, I.; Yadroitsava, I.; Bertrand, P.; Smurov, I. Factor Analysis of Selective Laser Melting Process Parameters and Geometrical Characteristics of Synthesized Single Tracks. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2012, 18, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolochko, N.K.; Mozzharov, S.E.; Yadroitsev, I.A.; Laoui, T.; Froyen, L.; Titov, V.I.; Ignatiev, M.B. Balling Processes during Selective Laser Treatment of Powders. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2004, 10, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Ma, S.; Liu, C.; Chen, C.; Wu, Q.; Chen, X.; Lu, J. Performance of High Layer Thickness in Selective Laser Melting of Ti6Al4V. Materials 2016, 9, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadroitsev, I.; Krakhmalev, P.; Yadroitsava, I.; Johansson, S.; Smurov, I. Energy Input Effect on Morphology and Microstructure of Selective Laser Melting Single Track from Metallic Powder. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2013, 213, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letenneur, M.; Kreitcberg, A.; Brailovski, V. Optimization of Laser Powder Bed Fusion Processing Using a Combination of Melt Pool Modeling and Design of Experiment Approaches: Density Control. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2019, 3, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.S.; Xue, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.Y.; Xiong, L.; Ni, H.W. Investigation on the Characteristics of Porosity, Melt Pool in 316L Stainless Steel Manufactured by Laser Powder Bed Fusion. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 32, 1832–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Plessis, A. Effects of Process Parameters on Porosity in Laser Powder Bed Fusion Revealed by X-Ray Tomography. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 30, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Hu, Y.; Ning, F.; Cong, W. Ultrasonic Vibration-Assisted Laser Engineered Net Shaping of Inconel 718 Parts: Effects of Ultrasonic Frequency on Microstructural and Mechanical Properties. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 276, 116395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Chen, W.; Wang, D.; Hou, H.; Zhao, Y. Phase-Field Modeling and Experimental Investigation for Rapid Solidification in Wire and Arc Additive Manufacturing. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 28, 4585–4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Shi, R.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Du, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, J. Phase-Field Simulation of Lack-of-Fusion Defect and Grain Growth during Laser Powder Bed Fusion of Inconel 718. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2023, 30, 2224–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Width | Depth |

|---|---|---|

| Best features | ‘Power’, ‘Scan speed’, ‘Input energy’, ‘Layer thickness’, ‘Si’ | ‘Power’, ‘Input energy’, ‘Beam size’, ‘Volume energy’, ‘Si’ |

| Target | ML Algorithm | Hyperparameters Optimized |

|---|---|---|

| Width | Support Vector Regression | C = 341, kernel = ‘linear’, epsilon = 11.610503225584356 (µm), tol = 0.5063349249279957 |

| Depth | Multi-layer Perceptron regressor | Hidden1: 331, Hidden2: 121, alpha: 0.05861435807687141, learning rate: 0.03472671856325738, batch_size: 38, momentum: 0.18279174066800405, tol: 0.009048802539977611 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jang, H.S.; Kim, S.; Jeon, J.B.; Kim, D.; Choi, Y.S.; Shin, S. Study on the Application of Machine Learning of Melt Pool Geometries in Silicon Steel Fabricated by Powder Bed Fusion. Materials 2026, 19, 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010068

Jang HS, Kim S, Jeon JB, Kim D, Choi YS, Shin S. Study on the Application of Machine Learning of Melt Pool Geometries in Silicon Steel Fabricated by Powder Bed Fusion. Materials. 2026; 19(1):68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010068

Chicago/Turabian StyleJang, Ho Sung, Sujeong Kim, Jong Bae Jeon, Donghwi Kim, Yoon Suk Choi, and Sunmi Shin. 2026. "Study on the Application of Machine Learning of Melt Pool Geometries in Silicon Steel Fabricated by Powder Bed Fusion" Materials 19, no. 1: 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010068

APA StyleJang, H. S., Kim, S., Jeon, J. B., Kim, D., Choi, Y. S., & Shin, S. (2026). Study on the Application of Machine Learning of Melt Pool Geometries in Silicon Steel Fabricated by Powder Bed Fusion. Materials, 19(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010068