Strength and Impact Toughness of Multilayered 7075/1060 Aluminum Alloy Composite Laminates Prepared by Hot Rolling and Subsequent Heat Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Microstructure Characterization

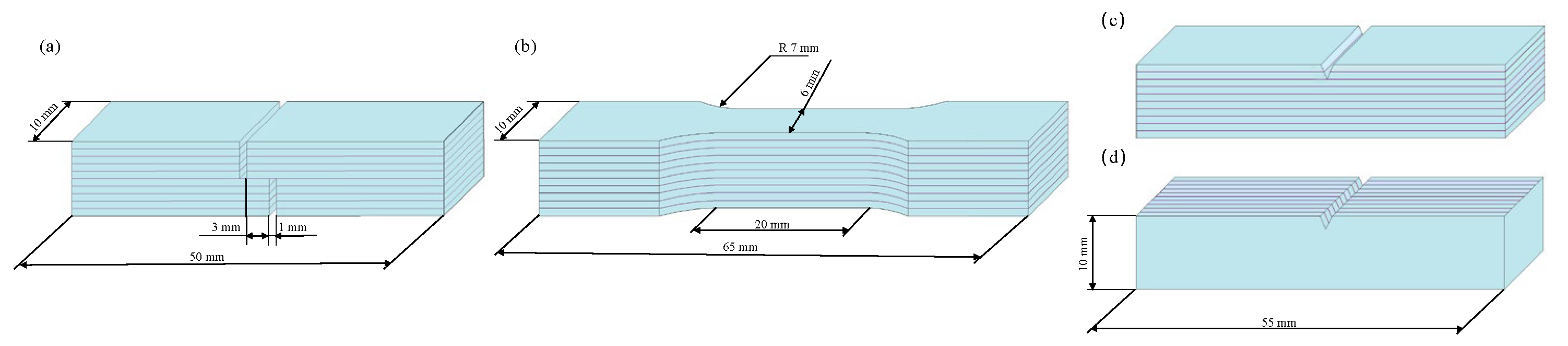

2.3. Mechanical Tests

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructures

3.2. Microhardness

3.3. Interface Shear Strength

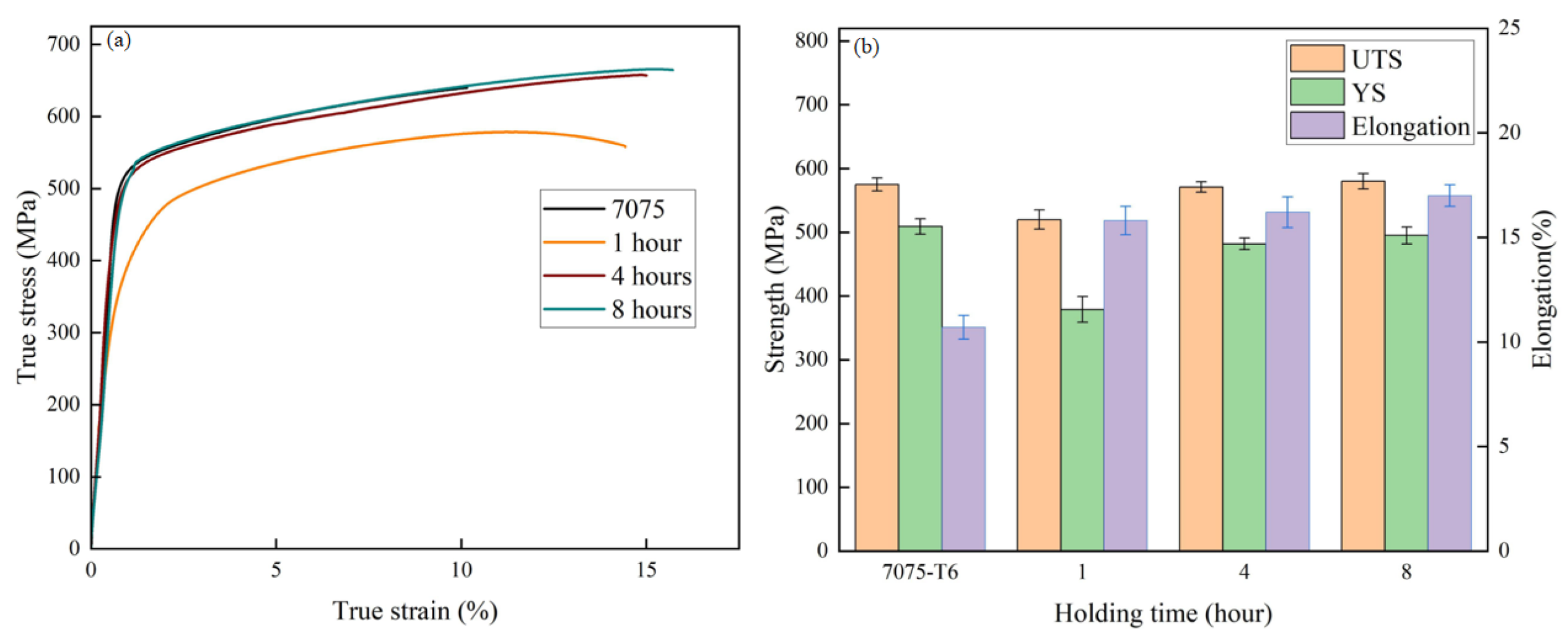

3.4. Tensile Properties

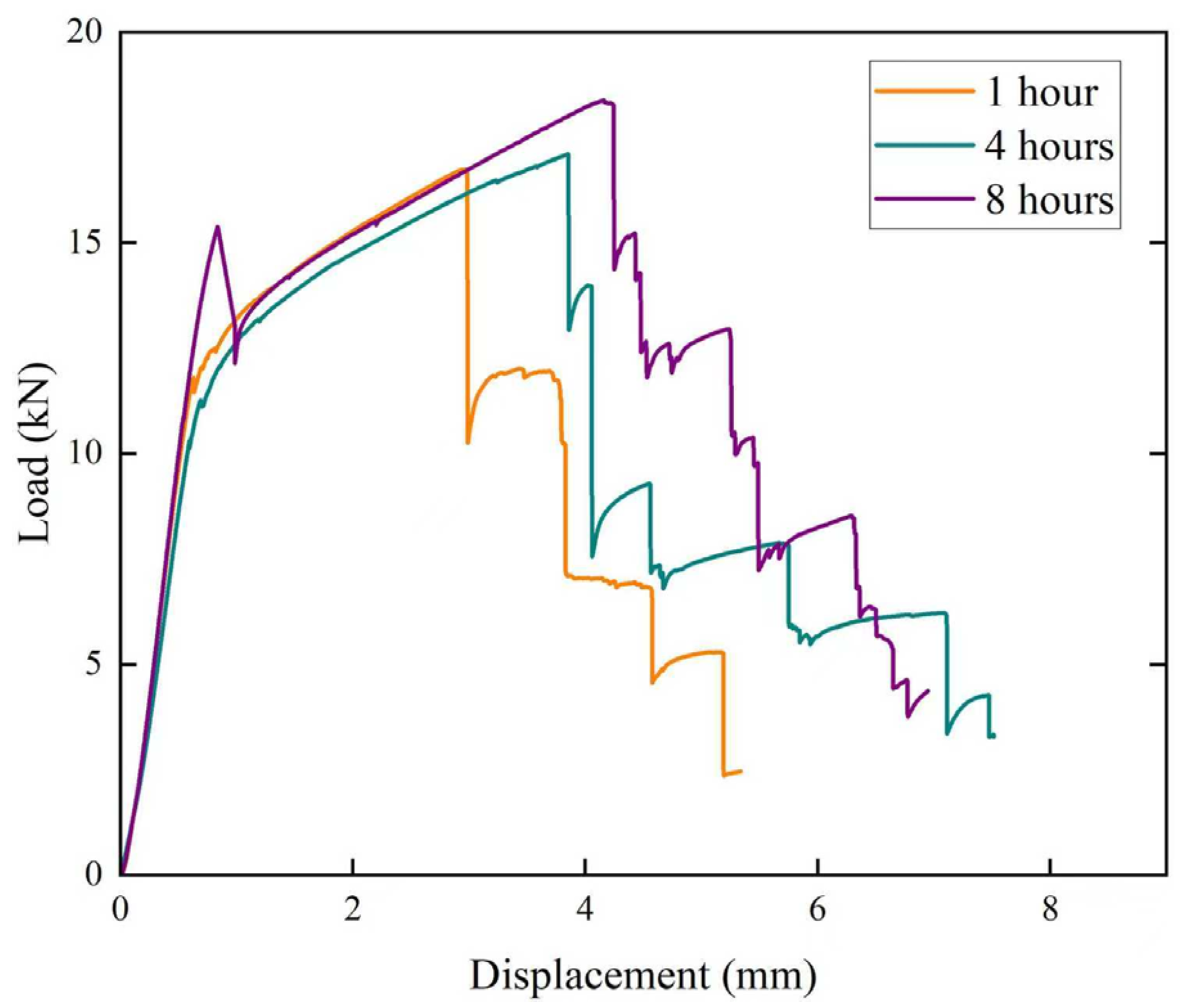

3.5. Three-Point Bending Test

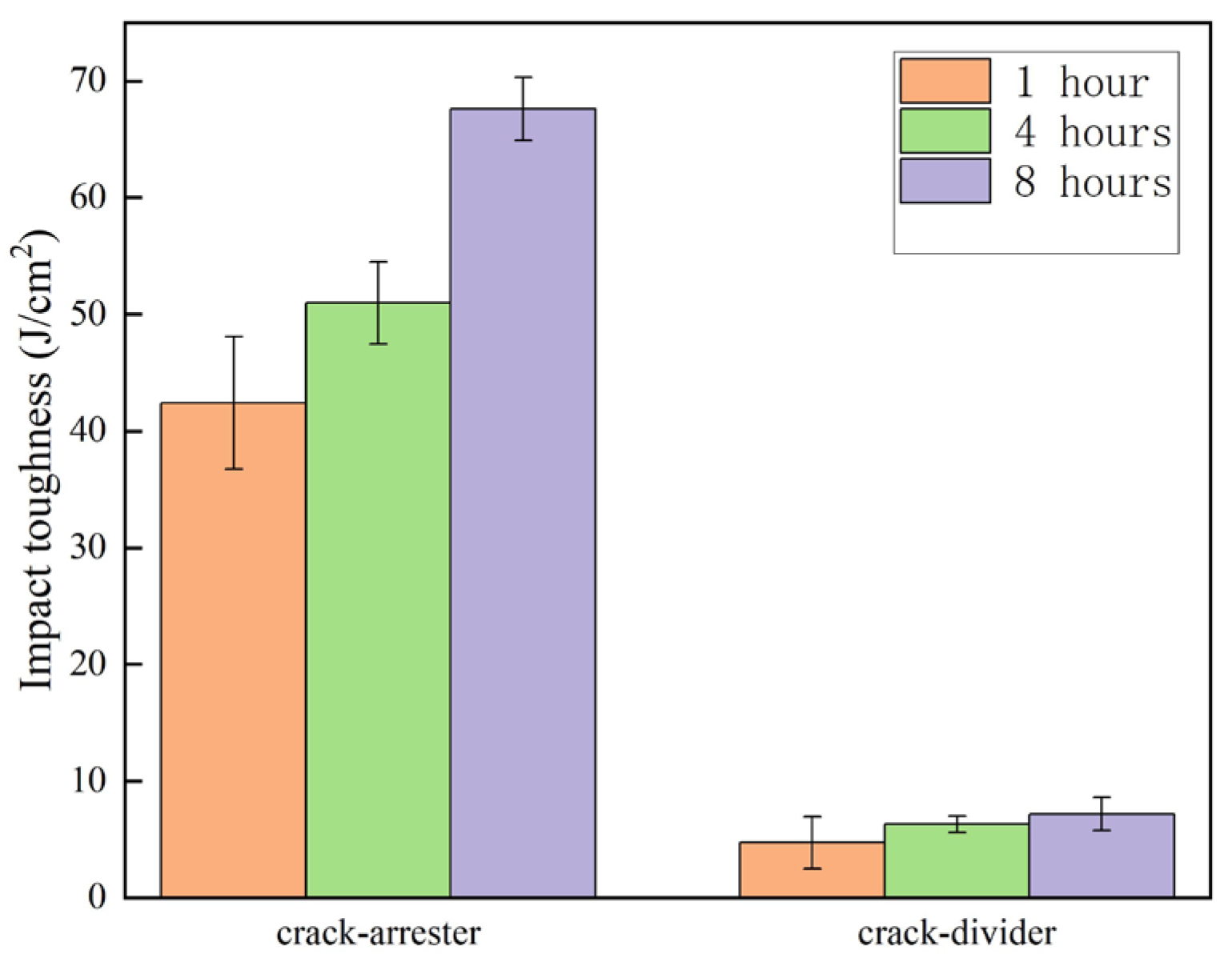

3.6. Charpy Impact Test

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- As the holding time increases at 470 °C, the concentrations of Zn and Mg elements dissolved in the 1060 layer increase, resulting in an enhanced solid solution strengthening effect. This leads to a simultaneous increase in the shear strength and shear displacement of the bonding interface with prolonged holding time, thereby achieving high interface toughness.

- (2)

- There is a dual increase in the tensile strength and elongation as the solution holding time increases. After a solution treatment of 8 h, the composite laminate exhibits higher tensile strength and elongation compared to the as-received T6-tempered 7075 monolithic plate. Notably, the elongation exhibited an increase of nearly 60% compared to that of the as-received T6-tempered 7075 monolithic plate.

- (3)

- The tensile, Charpy impact and bending properties are all positively correlated with the solution holding time. As the solution holding time increases, both interfacial delamination and the degree of main crack deflection increase in the Charpy impact and bending tests, which in turn lead to an improvement in both the laminate’s impact and bending properties.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, S.S.; Huang, G.S.; Gupta, M.; Jiang, B.; Pan, F.S. Microstructures, mechanical properties and deformation mechanism of heterogeneous metal materials: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2026, 248, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.T.; Ameyama, K.; Anderson, P.M.; Beyerlein, I.J.; Gao, H.J.; Kim, H.S.; Lavernia, E.; Mathaudhu, S.; Mughrabi, H.; Ritchie, R.O.; et al. Heterostructured materials: Superior properties from hetero-zone interaction. Mater. Res. Lett. 2021, 9, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, W.Z.; Wang, M.; Huang, G.S.; Zhang, J.L.; Pan, F.S. Optimizing the strength and ductility of pure aluminum laminate via tailoring coarse/ultrafine grain layer thickness ratio. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 7394–7406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.P.; Wu, H.; Miao, K.S.; Li, X.W.; Xu, C.; Geng, L.; Xie, H.L.; Fan, G.H. Effects of the layer thickness ratio on the enhanced ductility of laminated aluminum. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, B.X.; Zou, Q.; Huang, G.S.; Liu, S.S.; Zhang, J.L.; Tang, A.T.; Jiang, B.; Pan, F.S. Design of pure aluminum laminates with heterostructures for extraordinary strength-ductility synergy. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 100, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.H.; Chen, L.; Tang, J.W.; Li, Y.F.; Zhang, C.S.; Kong, X.S. Enhanced strength-ductility synergy of Mg/Al laminate by coordinating the strain gradient of constituting layers. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 233, 264–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Gu, G.H.; Kim, R.E.; Seo, M.H.; Kim, H.S. Deformation behavior of lightweight clad sheet: Experiment and modeling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 852, 143666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.N.; Hong, S.I. Interactive deformation and enhanced ductility of tri-layered Cu/Al/Cu clad composite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 651, 976–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, G.P. Delaying premature local necking of high-strength Cu: A potential way to enhance plasticity. Scr. Mater. 2011, 64, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yu, Q.; Wang, Z.; Ell, J.; Huang, M.X.; Ritchie, R.O. Making ultrastrong steel tough by grain-boundary delamination. Science 2020, 368, 1347–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozuelo, M.; Carreno, F.; Ruano, O. Innovative ultrahigh carbon steel laminates with outstanding mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Forum 2003, 426, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.W.; Euh, K.; Kang, J.H.; Cho, J.H. Effect of wire brushing on warm roll bonding of 6XXX/5XXX/6XXX aluminum alloy clad sheets. Mater. Des. 2012, 35, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, J.L.; Xia, D.B.; Huang, G.S.; Liu, K.; Jiang, B.; Tang, A.T.; Pan, F.S. Microstructure and mechanical properties of 1060/7050 laminated composite produced via cross accumulative extrusion bonding and subsequent aging. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 826, 154094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.J.; Jiang, H.S.X.; Bai, X.; Wang, Y.H.; Ni, X.B.; Li, X.W.; Wu, H.; Fu, W.J.; Fan, G.H.; Xia, Y.P. Enhanced strength-ductility synergy in multilayered aluminum via integrating dual-heterogeneous structures. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 935, 148379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Gu, C.Y.; Li, J.S.; Zhou, Z.C.; Lu, Y.; Gao, F.; Chen, M.; Mao, Q.Z.; Lu, X.K.; Li, Y.S. Effect of structural orientation on the impact properties of a soft/hard copper/brass laminate. Vacuum 2021, 191, 110388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, H.; Jamaati, R. Simultaneous improvement of strength and toughness in Al–Zn–Mg–Cu/pure Al laminated composite via heterogeneous microstructure. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 880, 145362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, T.Q.; Chen, Z.J.; Zhou, Z.S.; Liu, J.J.; He, W.J.; Liu, Q. Enhancing of mechanical properties of rolled 1100/7075 Al alloys laminated metal composite by thermomechanical treatments. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 800, 140313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 228.1-2021; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. National Standards of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- ASTM E23; Standard Test Methods for Notched Bar Impact Testing of Metallic Materials. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- Cepeda-Jiménez, C.M.; Pozuelo, M.; Ruano, O.A.; Carreño, F. Influence of the thermomechanical processing on the fracture mechanisms of high strength aluminium/pure aluminium multilayer laminate materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 490, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Jiménez, C.M.; Hidalgo, P.; Pozuelo, M.; Ruano, O.A.; Carreño, F. Influence of constituent materials on the impact toughness and fracture mechanisms of hot-roll-bonded aluminum multilayer laminates. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2009, 41, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Luo, Z.A.; Xie, G.M.; Yu, H.; Liu, Z.S.; Yang, J.S. Effect of annealing process on the interfacial microstructure evolution and mechanical properties of 7050 aluminum alloy clad plates. Mater. Lett. 2022, 324, 132608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.C.; Xu, Y.L.; Ran, H.; Fan, G.H.; Gao, S.; Tsuji, N.; Huang, C.X.; Gao, H.J.; Zhang, Y.W. The role of layer strength ratio in enhancing strain hardening and achieving strength-ductility synergy in heterostructured materials. Acta Mater. 2025, 289, 120928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.L.; Huang, C.X.; Moering, J.; Ruppert, M.; Höppel, H.W.; Göken, M.; Narayan, J.; Zhu, Y.T. Mechanical properties of copper/bronze laminates: Role of interfaces. Acta Mater. 2016, 116, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Huang, C.X.; Fang, X.T.; Höppel, H.W.; Göken, M.; Zhu, Y.T. Hetero-deformation induced (HDI) hardening does not increase linearly with strain gradient. Scr. Mater. 2020, 174, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, T.Q.; Chen, Z.J.; Zhou, D.Y.; Lu, G.M.; Huang, Y.M.; Liu, Q. Effect of lamellar structural parameters on the bending fracture behavior of AA1100/AA7075 laminated metal composites. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 99, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.M.; Zhang, X.M.; Liu, S.D.; He, D.G.; Zhang, R. Effect of solution treatment on the strength and fracture toughness of aluminum alloy 7050. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 4138–4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Zhang, Y.A.; Yan, L.Z.; Li, X.W.; Li, Z.H.; Xiong, B.Q.; Yan, H.W.; Wen, K. Microstructure and surface of 2A12 aluminum alloy cladded with pure aluminum after solution treatment. Rare Met. 2020, 40, 2937–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Jiménez, C.M.; Pozuelo, M.; García-Infanta, J.M.; Ruano, O.A.; Carreño, F. Interface effects on the fracture mechanism of a high-toughness aluminum-composite laminate. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2009, 40, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozuelo, M.; Carreño, F.; Cepeda-Jiménez, C.M.; Ruano, O.A. Effect of hot rolling on bonding characteristics and impact behavior of a laminated composite material based on UHCS-1.35 Pct C. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2008, 39, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Huang, L.J.; An, Q.; Geng, L.; Liu, B.X. Dramatically enhanced impact toughness of two-scale laminate-network structured composites. Mater. Des. 2018, 140, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozuelo, M.; Cepeda-Jiménez, C.M.; Chao, J.; Carreño, F.; Ruano, O.A. Fracture toughness for interfacial delamination of Cr–Mo steel multilayer laminate. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2009, 25, 632–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-Jiménez, C.M.; Carreño, F.; Ruano, O.A.; Sarkeeva, A.A.; Kruglov, A.A.; Lutfullin, R.Y. Influence of interfacial defects on the impact toughness of solid state diffusion bonded Ti–6 Al–4 V alloy based multilayer composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 563, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besson, J.; Madi, Y.; Motarjemi, A.; Koçak, M.; Martin, G.; Hornet, P. Crack initiation and propagation close to the interface in a ferrite–austenite joint. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 397, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gao, B.; Wei, K.; Hu, Z.H.; Yu, Y.D.; Sun, W.W.; Sui, Y.D.; Xiao, L.R.; Chen, X.F.; Zhou, H. Improved impact toughness of laminate heterogeneous AZ31/GW103K alloys by interface delamination. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 871, 144882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, W.B.; Mao, Q.Z.; Kang, J.J.; Liu, Y.Y.; Shu, D.; She, D.S.; Liu, Y.F.; Li, J.S. Superior impact property and fracture mechanism of a multilayered copper/bronze laminate. Mater. Lett. 2019, 250, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.M.; Liu, W.H.; Hu, Q.; Liu, X.; Zhu, B.W.; Wu, J.Z.; Ye, F. Regulation of solution treatment to improve the interfacial bonding quality and mechanical properties of 7B52 laminated aluminum alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1014, 178659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K.K.; Wen, H.M.; Hu, T.; Topping, T.D.; Isheim, D.; Seidman, D.N.; Lavernia, E.J.; Schoenung, J.M. Mechanical behavior and strengthening mechanisms in ultrafine grain precipitation-strengthened aluminum alloy. Acta Mater. 2014, 62, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Zn | Mg | Cu | Fe | Mn | Cr | Ti | Zr | Si | Al | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7075 | 5.9 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.14 | Bal. |

| 1060 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.15 | 0.01 | - | 0.01 | - | 0.13 | Bal. |

| UTS (MPa) | YS (MPa) | Elongation (Pct.) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7075-T6 | 575 ± 25 * | 509 ± 30 * | 10.7 ± 1.4 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; He, S.; Wang, Q.; Cong, F.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y. Strength and Impact Toughness of Multilayered 7075/1060 Aluminum Alloy Composite Laminates Prepared by Hot Rolling and Subsequent Heat Treatment. Materials 2026, 19, 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010062

Zhang H, Liu S, He S, Wang Q, Cong F, Zhang Y, Cao Y. Strength and Impact Toughness of Multilayered 7075/1060 Aluminum Alloy Composite Laminates Prepared by Hot Rolling and Subsequent Heat Treatment. Materials. 2026; 19(1):62. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010062

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Hui, Shida Liu, Siqi He, Qunjiao Wang, Fuguan Cong, Yunlong Zhang, and Yu Cao. 2026. "Strength and Impact Toughness of Multilayered 7075/1060 Aluminum Alloy Composite Laminates Prepared by Hot Rolling and Subsequent Heat Treatment" Materials 19, no. 1: 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010062

APA StyleZhang, H., Liu, S., He, S., Wang, Q., Cong, F., Zhang, Y., & Cao, Y. (2026). Strength and Impact Toughness of Multilayered 7075/1060 Aluminum Alloy Composite Laminates Prepared by Hot Rolling and Subsequent Heat Treatment. Materials, 19(1), 62. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010062