Effect of Silicon and Continuous Annealing Process on the Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Hydrogen Embrittlement of DP1500 Steel

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Experimental Procedure

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. Heat Treatment Process

2.3. Microstructure Characterization

2.4. Mechanical Performance Test

2.5. Hydrogen Embrittlement Sensitivity Test

3. Experimental Results

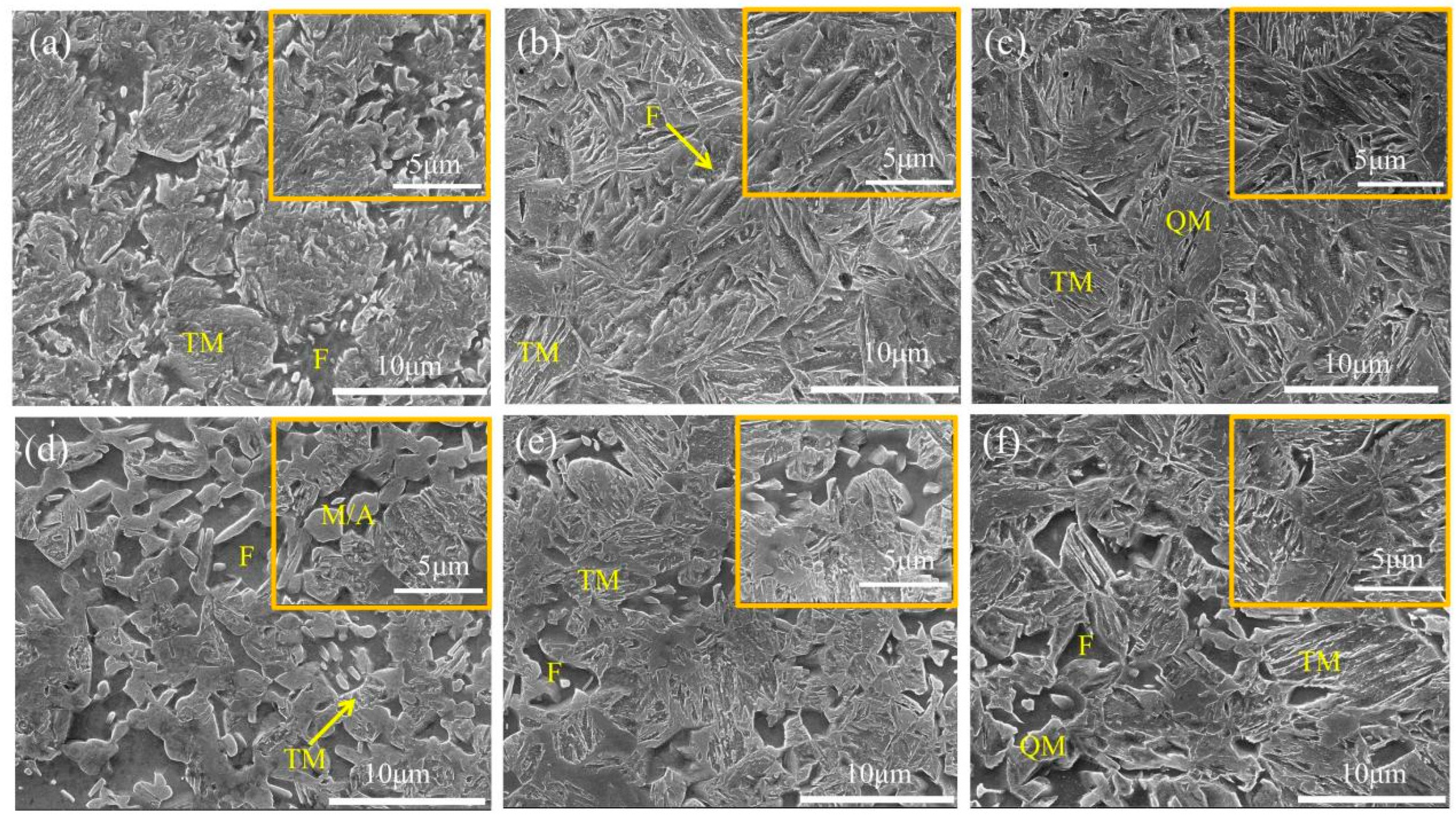

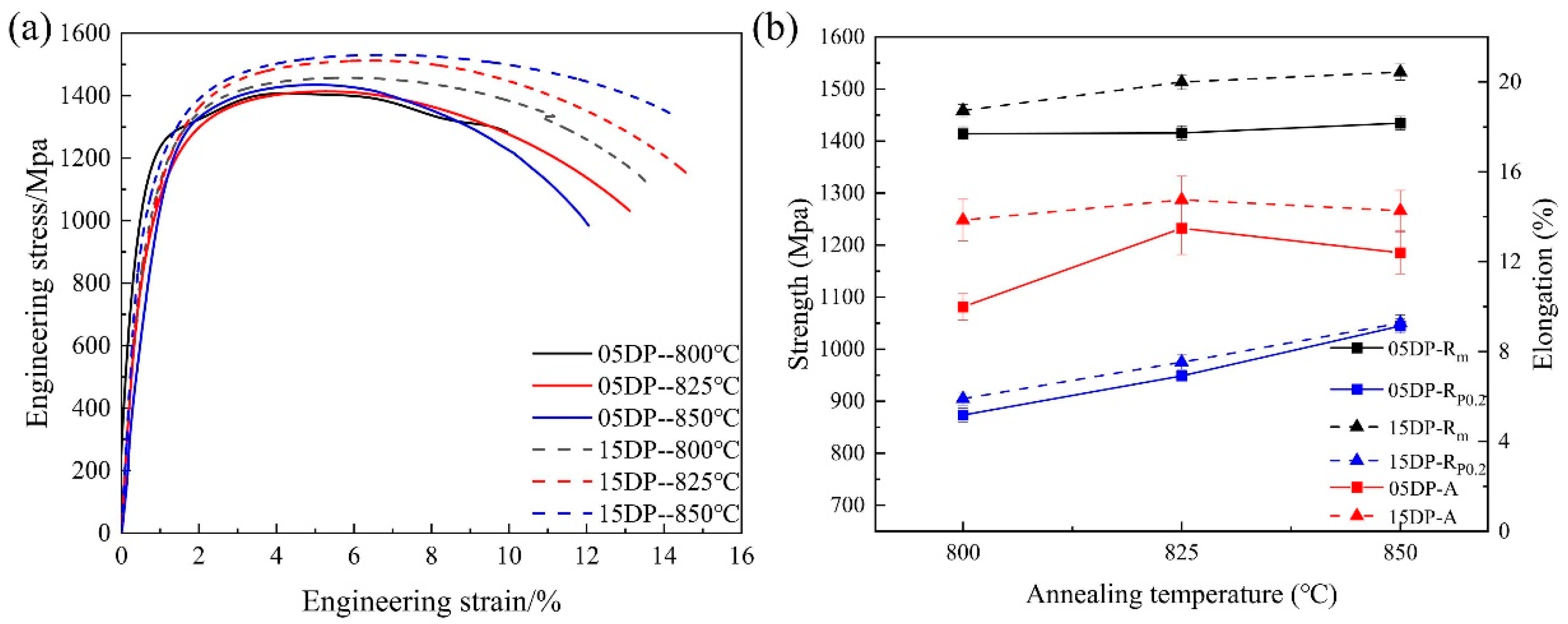

3.1. Effect of Annealing Temperature on the Microstructure of DP1500 Steels

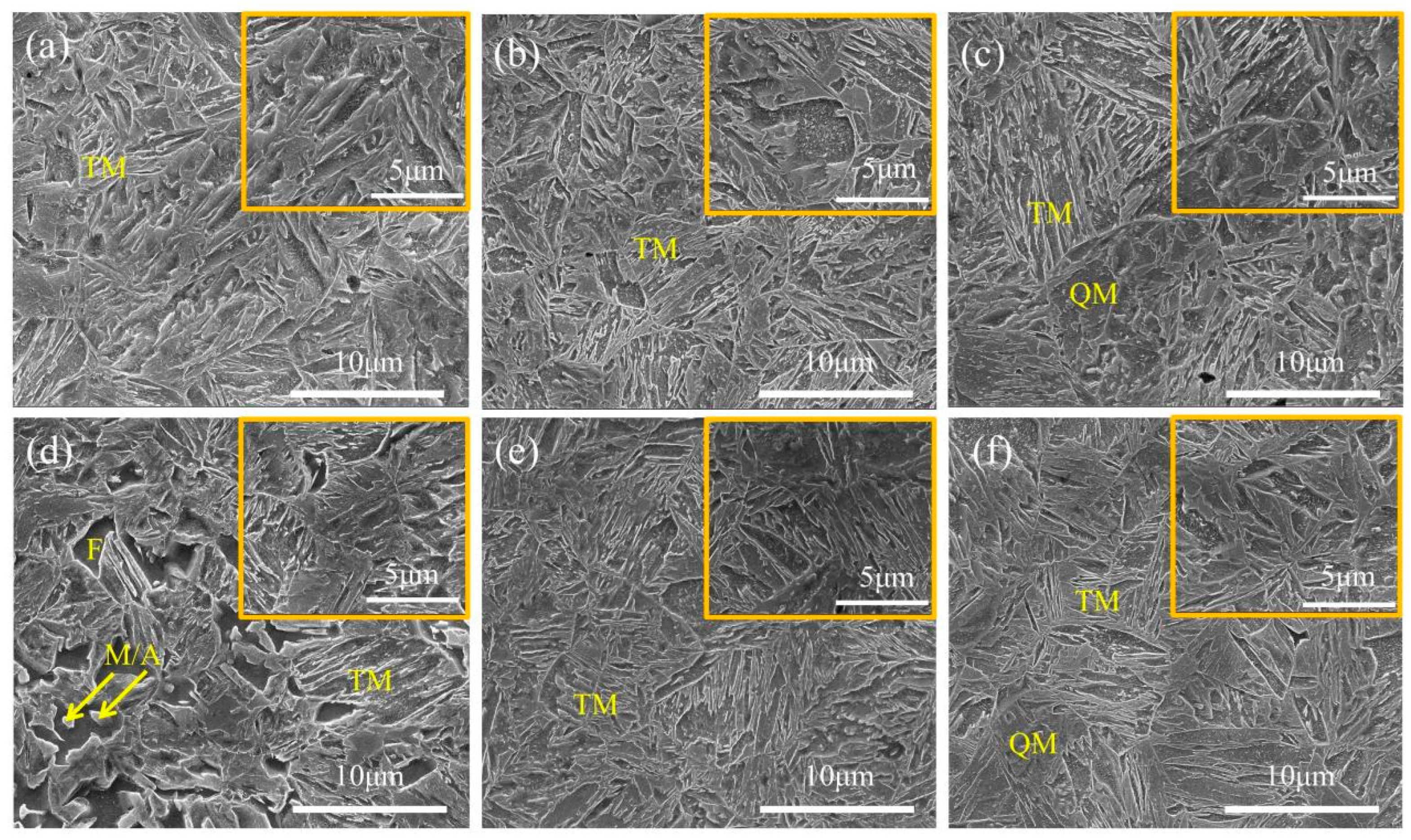

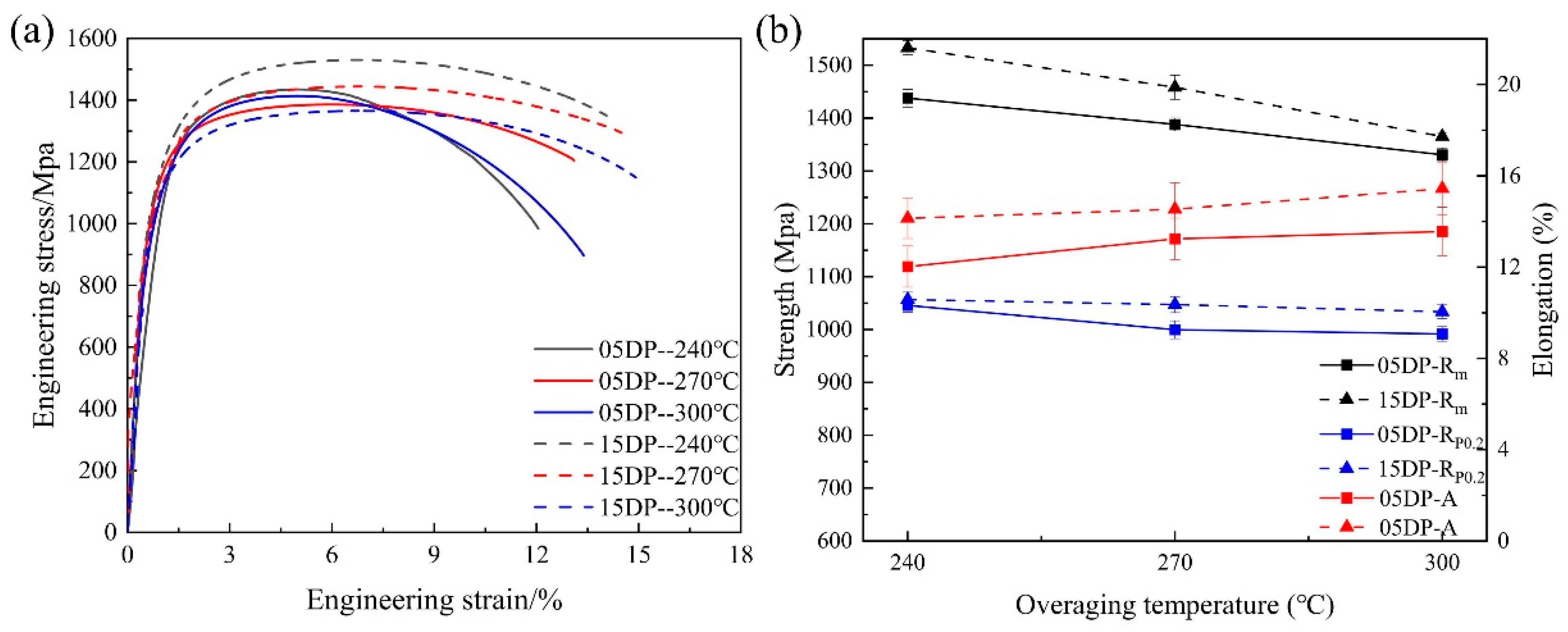

3.2. Effect of Over-Aging Temperature on DP1500 Steels

3.3. Microstructural Characterization of DP1500 Steels

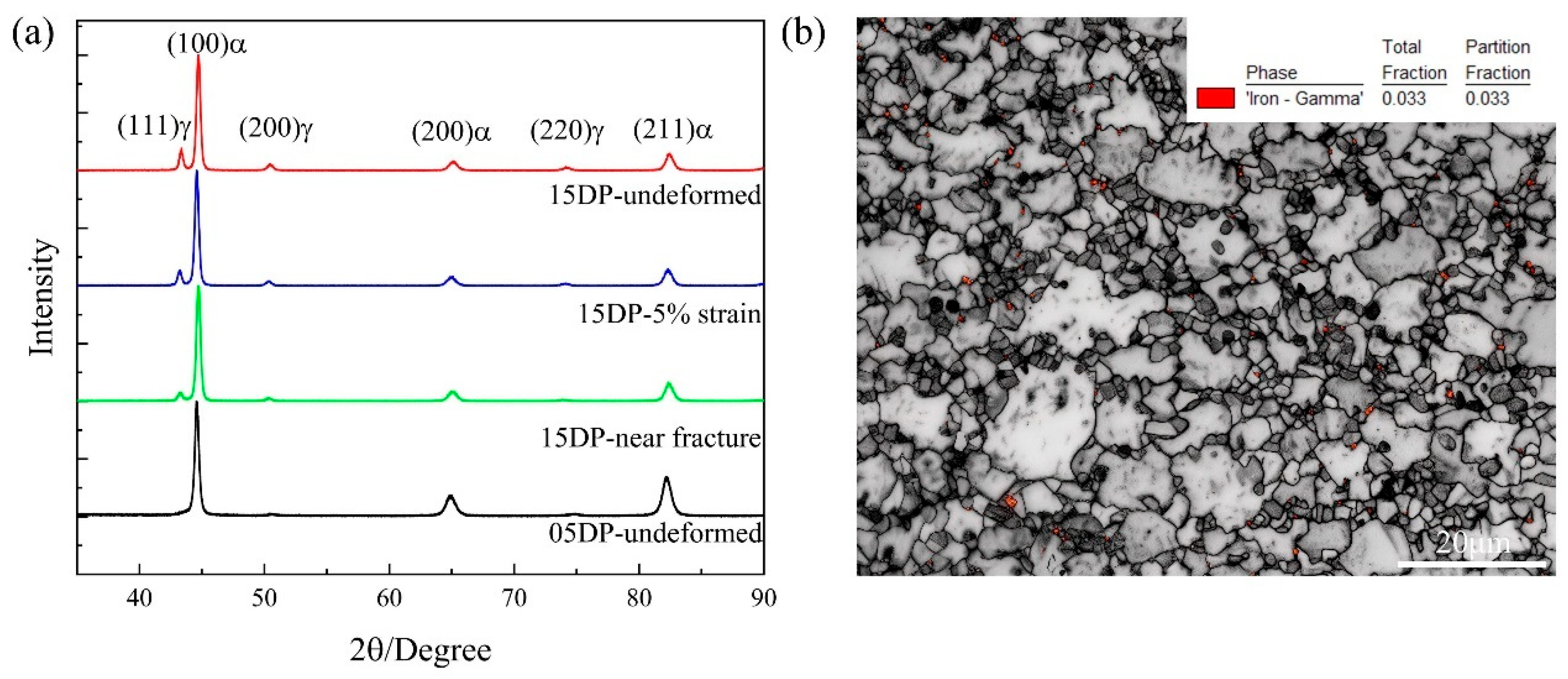

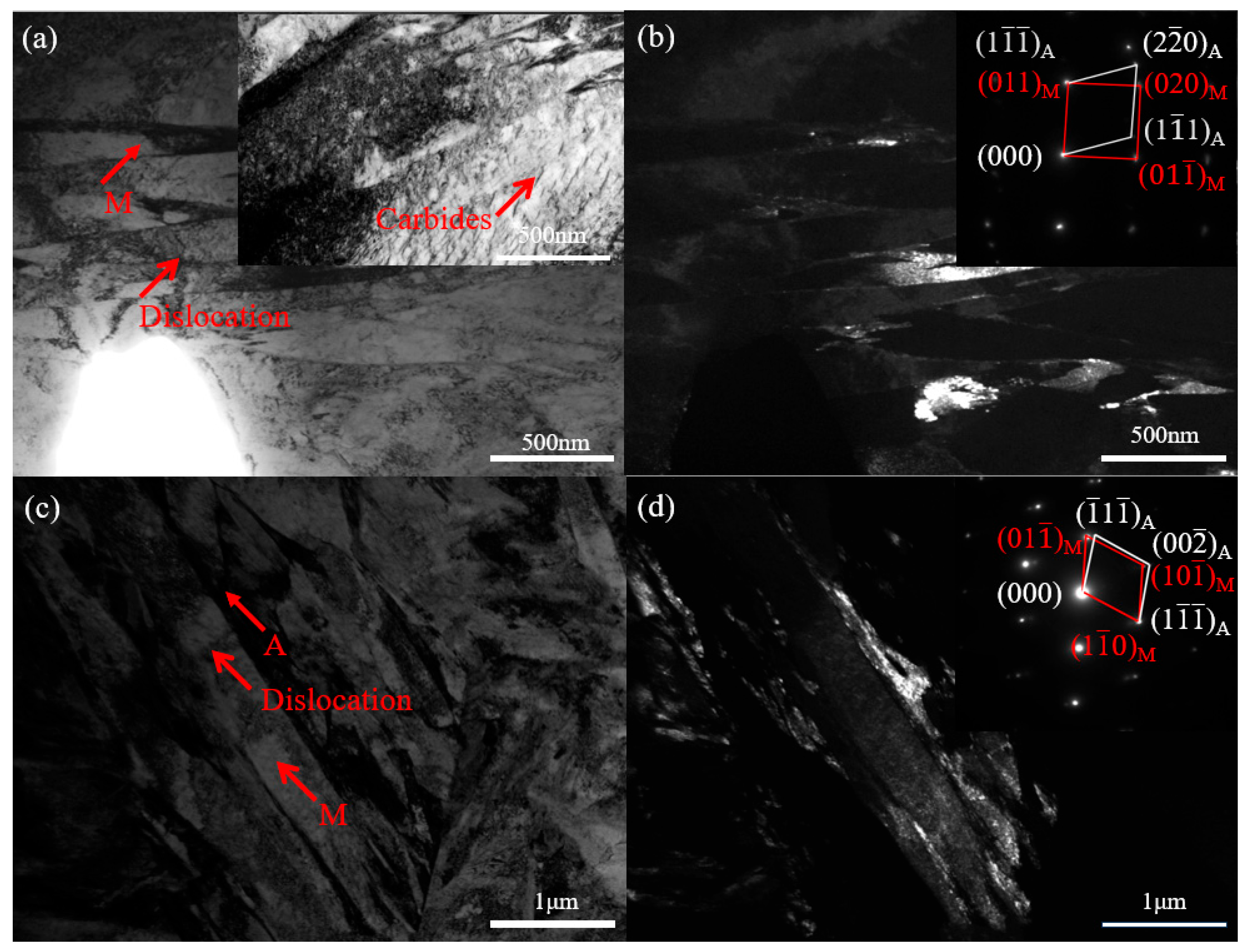

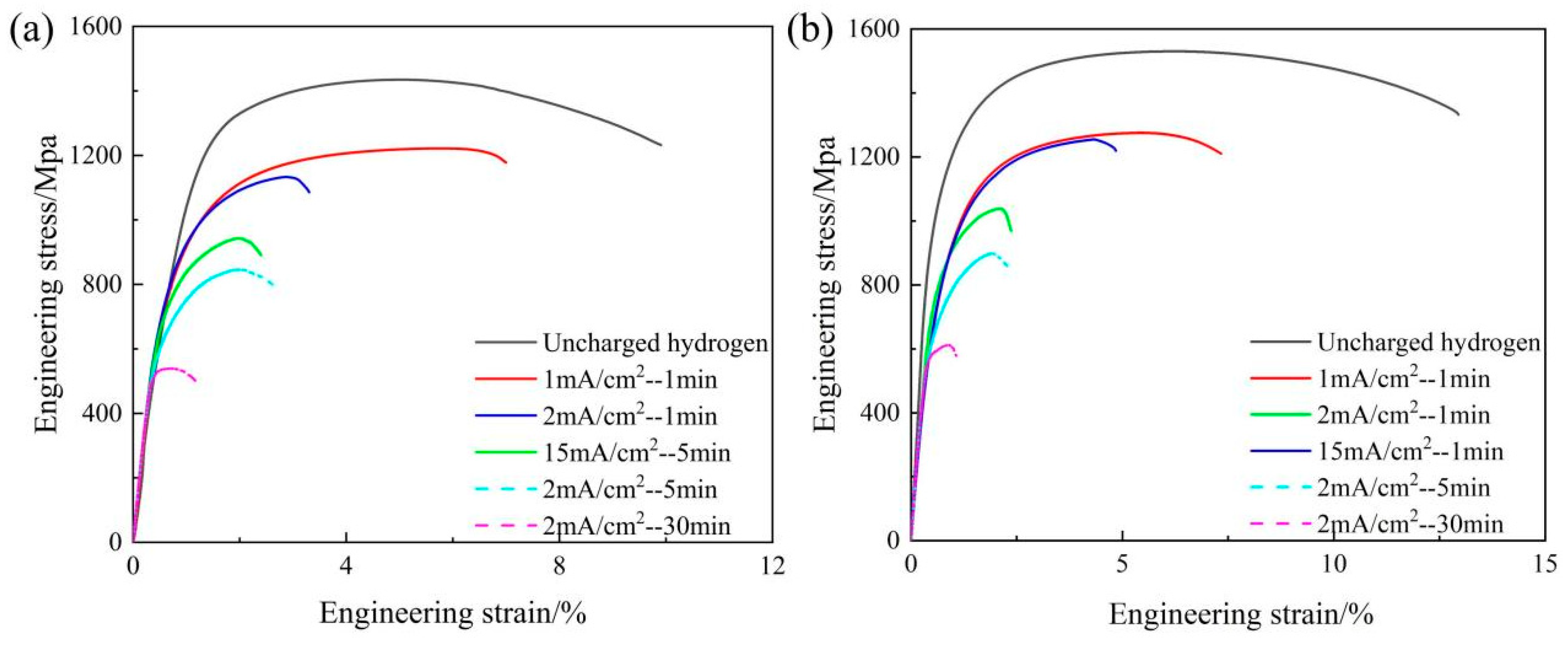

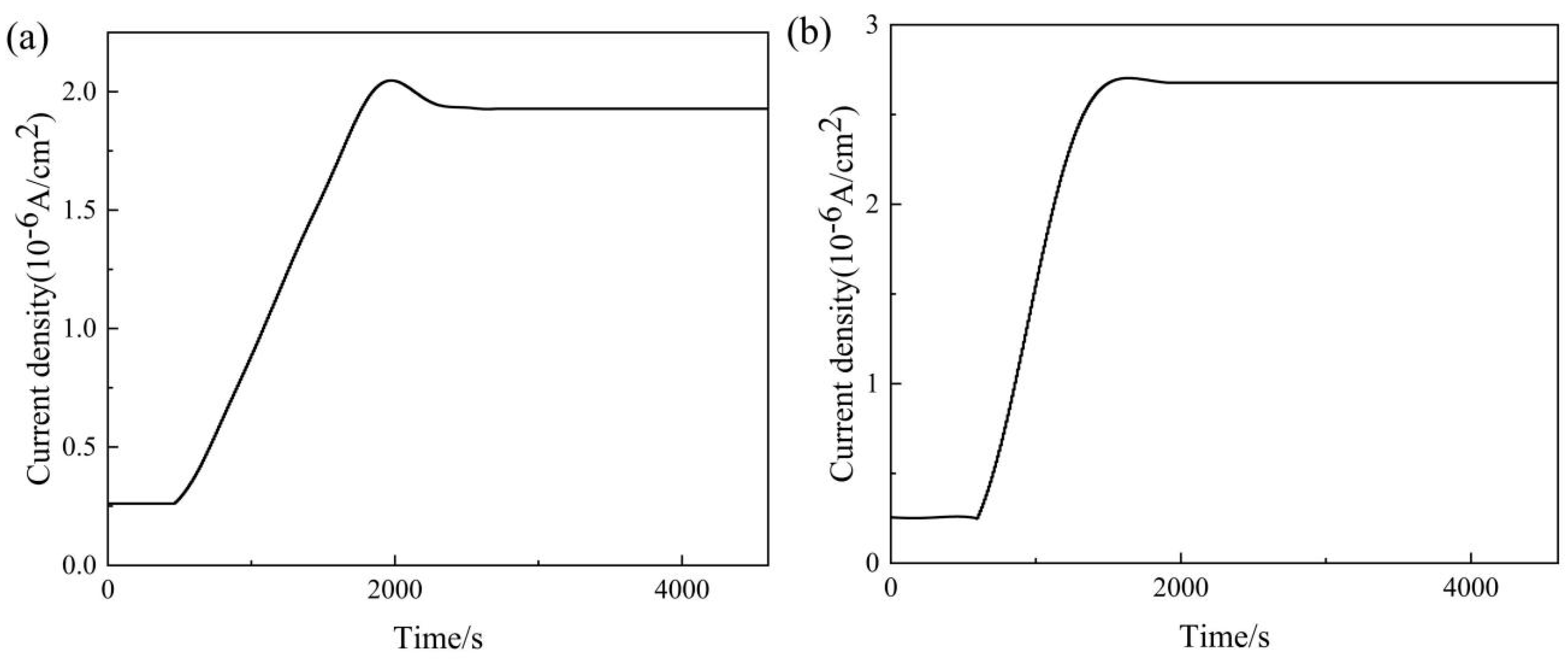

3.4. Hydrogen Embrittlement Sensitivity of DP1500 Steels

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Si Content on Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of DP1500 Steels

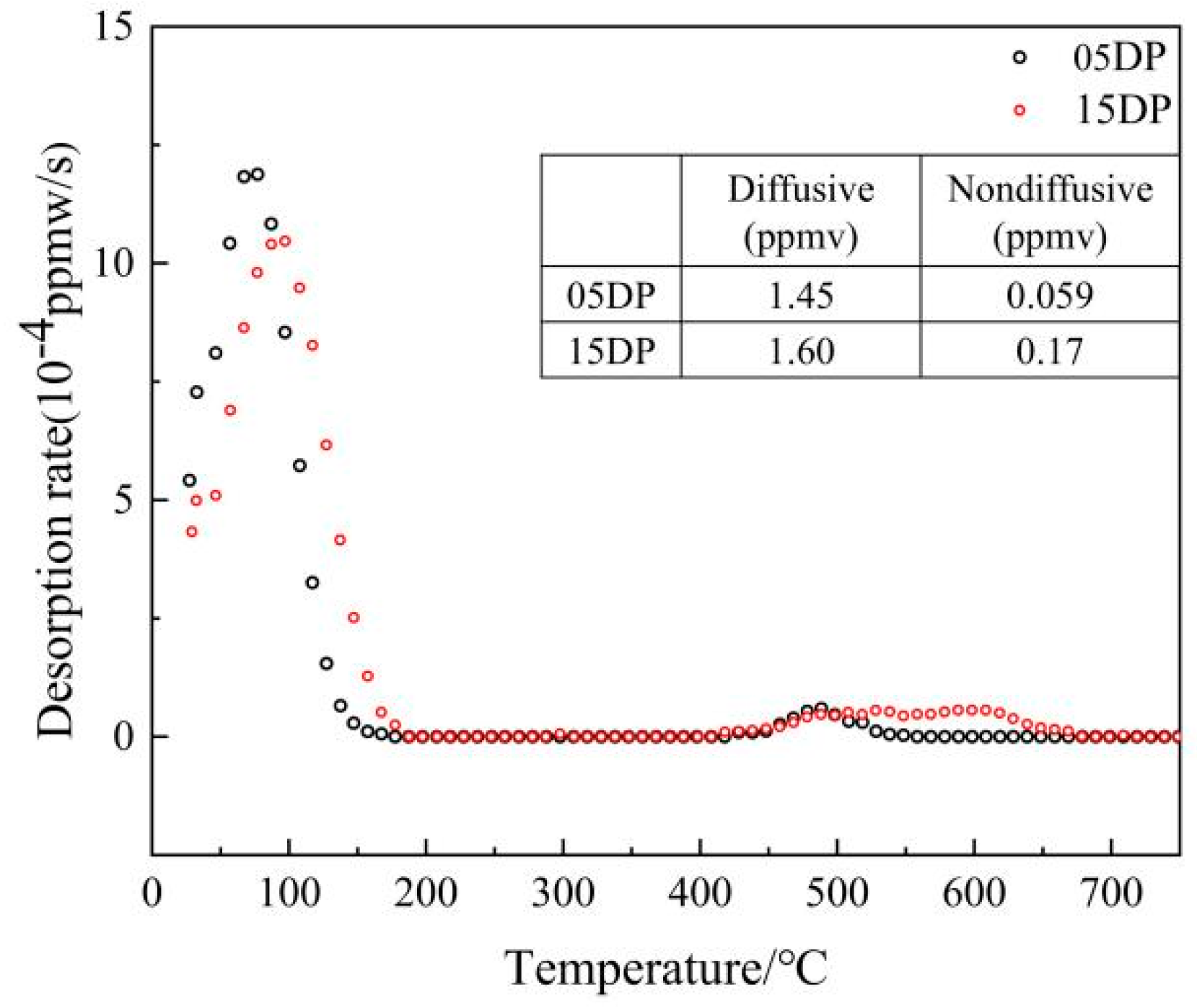

4.2. Effect of Si Content on Hydrogen Embrittlement Susceptibility of DP1500 Steels

5. Conclusions

- By designing an appropriate continuous annealing process, DP steel with a tensile strength greater than 1500 MPa and an elongation close to 15% can be obtained, which possesses excellent mechanical properties.

- The increase in Si content purify the ferrite matrix, inhibit the precipitation of carbides, enrich carbon in the austenite, increase the content of ferrite and retained austenite in the microstructure, and utilize the TRIP effect to further enhance the strength and plasticity of 15DP steel.

- Although the increase in Si content enhanced carbon enrichment in austenite and refined the ferrite–martensite structure, thereby significantly improving strength and ductility, the fresh martensite formed either by strain-induced TRIP during deformation or after over-aging exhibited relatively high hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility. Consequently, despite the higher fraction and improved stability of retained austenite, 15DP steel did not exhibit substantially better HE resistance than 05DP steel.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xia, P.K.; Sabirov, I.; Petrov, R.; Verleysen, P. Review of Performance of Advanced High Strength Steels under Impact. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27, 2402016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Q.; Shi, J.Q.; Fan, Y.H.; Ma, C.; Dong, X.L.; Guo, C.W.; Zhao, H.L. The effect of intercritical annealing time on the hydrogen embrittlement of dual-phase steel. Mater. Today Commum. 2024, 38, 108328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlock, D.K.; Kang, S.; De Moor, E.; Speer, J.D. Applications of rapid thermal processing to advanced high strength sheet steel developments. Mater. Charact. 2020, 166, 110397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimani, M.; Kalhor, A.; Mirzadeh, H. Transformation-induced plasticity (TRIP) in advanced steels: A review. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 795, 140023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meknassi, R.F.; Miklós, T. Third generation of advanced high strength sheet steels for the automotive sector: A literature review. Multidiszcip. Tudományok 2021, 11, 241–247. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, B.; Ma, A.; Fathi, R.; Radhika, N.; Yang, G.H.; Jiang, J.H. Optimized mechanical properties of magnesium matrix composites using RSM and ANN. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2023, 290, 116303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, H.; Sun, Q.; Wang, X.; Li, J. Microstructure and properties in dissimilar/similar weld joints between DP780 and DP980 steels processed by fiber laser welding. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2017, 33, 1561–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.; Chen, T.; Kong, L.; Wang, M.; Pan, H.; Lei, M. Liquid metal embrittlement cracking during resistance spot welding of galvanized Q&P980 steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2019, 50, 5128–5142. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Venezuela, J.; Zhang, M.; Atrens, A. The role of the microstructure on the influence of hydrogen on some advanced high-strength steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 715, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Z.D.; Somerday, B.P. Hydrogen embrittlement of steels: Mechanical properties in gaseous hydrogen. Int. Mater. Rev. 2025, 70, 394–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ronevich, J.; Agnani, M.; Marchi, S.C. Microstructure and mechanical performance of X120 linepipe steel in high-pressure hydrogen gas. In Proceedings of the Pressure Vessels and Pi** Conference, Bellevue, WA, USA, 28 July–2 August 2024; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 88506, p. V004T06A014. [Google Scholar]

- Koyama, M.; Akiyama, E.; Tsuzaki, K.; Raabe, D. Hydrogen-assisted failure in a twinning-induced plasticity steel studied under in situ hydrogen charging by electron channeling contrast imaging. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 4607–4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.Y.; Stodolna, J.; Todeschini, P.; Todeschini, P.; Delabrouille, F.; Christien, F. Effect of bainitic or martensitic microstructure of a pressure vessel steel on grain boundary segregation induced by step cooling simulating thermal aging. J. Nucl. Mater. 2023, 584, 154554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, G.S.; Yagodzinskyy, Y.; Que, Z.; Yagodzinskyy, Y.; Que, Z.; Spätig, P.; Seifert, H.P. Study on hydrogen embrittlement and dynamic strain ageing on low-alloy reactor pressure vessel steels. J. Nucl. Mater. 2021, 556, 153161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yan, Y.; Li, J.; JHuang Qiao, L.; Volinsky, A.A. Microstructure effect on hydrogen-induced cracking in TM210 maraging steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 586, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peet, M.J.; Hojo, T. Hydrogen susceptibility of nanostructured bainitic steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2016, 47, 718–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa, D.; Robinson, M.J. The effects of sacrificial coatings on hydrogen embrittlement and re-embrittlement of ultra high strength steels. Corros. Sci. 2008, 50, 1066–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girault, E.; Mertens, A.; Jacques, P.; Houbaert, Y.; Verlinden, B.; Humbeeck, J.V. Comparison of the effects of silicon and aluminium on the tensile behaviour of multiphase TRIP-assisted steels. Scr. Mater. 2001, 44, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnoka, M.; Jack, T.A.; Szpunar, J. Effects of different microstructural parameters on the corrosion and cracking resistance of pipeline steels: A review. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2024, 159, 108065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugaiyan, A.; Saha Podder, A.; Pandit, A.; Chandra, S. Phase transformations in two C-Mn-Si-Cr dual phase steels. ISIJ Int. 2006, 46, 1489–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Díaz, A.; Lu, X.; Sun, B.; Ding, Y.; Koyama, M.; Zhang, Z. Hydrogen embrittlement as a conspicuous material challenge—Comprehensive review and future directions. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 6271–6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.H.; Priestner, R. Retained austenite in dual-phase silicon steels and its effect on mechanical properties. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 113, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, J.Y.; Thomas, G. Design of duplex Fe/X/0.1C steels for improved mechanical properties. Metall. Trans. A 1977, 8, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonstein, N. Advanced High Strength Sheet Steels Physical Metallurgy, Design, Processing, and Properties; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hironaka, S.; Tanaka, H.; Matsumoto, T. Effect of Si on mechanical property of galvannealed dual phase steel. In Materials Science Forum; Trans Tech Publications Ltd.: Baech, Switzerland, 2010; Volume 638, pp. 3260–3265. [Google Scholar]

- Nouri, A.; Saghafian, H.; Kheirandish, S. Effects of silicon content and intercritical annealing on manganese partitioning in dual-phase steels. ISIJ Int. 2010, 17, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redhead, P.A. Thermal desorption of gases. Vacuum 1962, 12, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Tong, T.; Zhao, A.; He, Q.; Dong, R.; Zhao, F. Microstructure, mechanical properties and work hardening behavior of 1300 MPa grade 0.14 C-2.72 Mn-1.3 Si steel. Acta Met. Sin. 2014, 50, 1153–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Kalashami, A.G.; DiGiovanni, C.; Razmpoosh, M.H.; Goodwin, F.; Zhou, N.Y. The effect of silicon content on liquid-metal-embrittlement susceptibility in resistance spot welding of galvanized dual-phase steel. J. Manuf. Process. 2020, 57, 370–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalashami, A.G.; DiGiovanni, C.; Razmpoosh, M.H.; Goodwin, F.; Zhou, N.Y. The role of internal oxides on the liquid metal embrittlement cracking during resistance spot welding of the dual phase steel. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2020, 51, 2180–2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.G.; Tomota, Y.; Arakaki, Y.; Harjo, S.; Sueyoshi, H. Evaluation of austenite volume fraction in TRIP steel sheets using neutron diffraction. Mater. Charact. 2017, 127, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Li, C.; Li, W.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, K. Effect of microstructure on hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility in quenching-partitioning-tempering steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 831, 142046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wu, Z.; Wu, G.; Zhao, Q.; Luo, J. Investigation on micromechanism of ferrite hardening after pre-straining with different strain rates of dual-phase steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 802, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Pei, Y.; Yan, J.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, J. Role of martensite morphology on mechanical response of dual-phase steel produced by partial reversion from martensite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 893, 146116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Pei, Y.; Han, H.; Feng, S.; Zhang, Y. A Novel Low-Cost Fibrous Tempered-Martensite/Ferrite Low-Alloy Dual-Phase Steel Exhibiting Balanced High Strength and Ductility. Materials 2025, 18, 1292. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Zhu, M.; Lan, B. The mechanism of high-strength quenching-partitioning-tempering martensitic steel at elevated temperatures. Crystals 2019, 9, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asari, D.; Mizokami, S.; Fukahori, M.; Takai, K. Comparison of Fracture Morphologies and Hydrogen States Present in the Vicinity of Fracture Surface Obtained by Different Methods of Evaluating Hydrogen Embrittlement of DP and TRIP Steels; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 1349, p. 1357. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X. Research on Hydrogen Embrittlement Mechanism of 3rd Generation Advanced High-Strength Automotive Steel Based on TRIP Effect. Ph.D. Thesis, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.W.; Yang, D.P.; Wang, G.D.; Yi, H.L. Bending deformation behavior of a 1000 MPa grade dual-phase steel with superior bending toughness. Mater. Lett. 2024, 354, 135303. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, M.; Guo, Z.; Chen, N.; Rong, Y. A new effect of retained austenite on ductility enhancement in high-strength quenching–partitioning–tempering martensitic steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 8486–8491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Chai, L.; Wang, H.; Li, G.; Murty, K.L. Strength-ductility synergy through tailoring heterostructures of hot-rolled ferritic-martensitic steels containing varying Si contents. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 886, 145712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manda, S.; Kumar, S.; Tripathy, R.R.; Sudhalkar, B.; Pai, N.N.; Basu, S. Origin of hydrogen embrittlement in ferrite-martensite dual-phase steel. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 100, 1266–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, A.; Bergmann, C.; Manke, G.; Kokotin, V.; Mraczek, K.; Pohl, M.; Ecker, W. On the local evaluation of the hydrogen susceptibility of cold-formed and heat treated advanced high strength steel (AHSS) sheets. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 800, 140276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, T.; Kömmelt, P.; Brouwer, H.J.; Böttger, A.; Popovich, V. Effect of titanium and vanadium nano-carbide size on hydrogen embrittlement of ferritic steels. npj Mater. Degrad. 2025, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depover, T.; Hajilou, T.; Wan, D.; Wang, D.; Barnoush, A.; Verbeken, K. Assessment of the potential of hydrogen plasma charging as compared to conventional electrochemical hydrogen charging on dual phase steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 754, 613–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Yang, X.S.; Qiao, L.; Pang, X. Quantitative investigation on deep hydrogen trapping in tempered martensitic steel. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 854, 157218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.Y.; Zhang, B.; Niu, R.; Lu, S.L.; Huang, C.; Wang, M.; Chen, Y.S. Engineering metal-carbide hydrogen traps in steels. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yu, S.; Li, W. Effect of microstructure on hydrogen trapping behavior and hydrogen embrittlement sensitivity of medium manganese steel. Anti-Corros. Methods Mater. 2025, 72, 364–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudomilova, D.; Prošek, T.; Salvetr, P.; Knaislová, A.; Novák, P.; Kodým, R. The effect of microstructure on hydrogen permeability of high strength steels. Mater. Corros. 2020, 71, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | C | Si | Mn | P | S | Al | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05DP | 0.22 | 0.53 | 2.44 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.036 | 0.004 |

| 15DP | 0.22 | 1.51 | 2.42 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 0.037 | 0.004 |

| Steel | Ac1 | Ac3 | Ms | Mf |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05DP | 738 | 920 | 402 | 212 |

| 15DP | 751 | 947 | 390 | 198 |

| Hydrogen Charging Current Density (mA/cm2) | Hydrogen Charging Time (min) | Rm (MPa) | Rp0.2 (MPa) | A (%) | Elloss (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05DP | 0 | 0 | 1434.93 ± 18.7 | 1043.6 ± 12.3 | 12.06 ± 1.54 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1215.87 ± 26.4 | 794.6 ± 18.9 | 7.79 ± 1.71 | 35.4% | |

| 2 | 1 | 1132.95 ± 33.5 | 645.8 ± 24.1 | 5.22 ± 1.86 | 54.2% | |

| 15 | 1 | 942.45 ± 41.6 | 650.5 ± 29.8 | 3.22 ± 1.93 | 73.3% | |

| 2 | 5 | 845.72 ± 47.2 | 508.8 ± 33.5 | 3.87 ± 1.05 | 67.9% | |

| 2 | 30 | 538.60 ± 52.9 | 480.2 ± 38.1 | 1.63 ± 1.14 | 86.5% | |

| 15DP | 0 | 0 | 1530.41 ± 17.5 | 1055.5 ± 11.6 | 14.24 ± 1.57 | 0 |

| 1 | 1 | 1274.48 ± 28.4 | 836.8 ± 20.4 | 11.45 ± 1.69 | 19.5% | |

| 2 | 1 | 1254.38 ± 35.9 | 808.7 ± 26.7 | 8.89 ± 1.92 | 37.5% | |

| 15 | 1 | 1037.22 ± 43.1 | 722.5 ± 31.4 | 4.94 ± 1.02 | 65.3% | |

| 2 | 5 | 897.03 ± 46.5 | 662.4 ± 35.9 | 3.39 ± 1.11 | 76.2% | |

| 2 | 30 | 607.75 ± 51.7 | 507.3 ± 39.6 | 2.89 ± 1.23 | 79.7% |

| Hydrogen Permeation Experiments | 05DP Steel | 15DP Steel |

|---|---|---|

| L (cm) | 0.048 | 0.046 |

| I∞L (A/cm2) | 1.93 × 10−6 | 2.68 × 10−6 |

| tL (s) | 1330 | 850 |

| J∞L (mol cm−1s−1) | 1.24 × 10−12 | 8.53 × 10−13 |

| Deff (cm2 s−1) | 2.87 × 10−7 | 1.14 × 10−7 |

| Capp (mol cm−3) | 4.32 × 10−6 | 7.48 × 10−6 |

| NT (cm−3) | 3.86 × 1020 | 1.68 × 1021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Tang, Y.; Cao, B.; Jiang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, K. Effect of Silicon and Continuous Annealing Process on the Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Hydrogen Embrittlement of DP1500 Steel. Materials 2026, 19, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010006

Li W, Tang Y, Cao B, Jiang Y, Shen Y, Li W, Zhang K. Effect of Silicon and Continuous Annealing Process on the Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Hydrogen Embrittlement of DP1500 Steel. Materials. 2026; 19(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Wei, Yu Tang, Boyu Cao, Yeqian Jiang, Yang Shen, Wei Li, and Ke Zhang. 2026. "Effect of Silicon and Continuous Annealing Process on the Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Hydrogen Embrittlement of DP1500 Steel" Materials 19, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010006

APA StyleLi, W., Tang, Y., Cao, B., Jiang, Y., Shen, Y., Li, W., & Zhang, K. (2026). Effect of Silicon and Continuous Annealing Process on the Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, and Hydrogen Embrittlement of DP1500 Steel. Materials, 19(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010006