Tailoring Microstructure and Properties of CoCrNiAlTiNb High-Entropy Alloy Coatings via Laser Power Control During Laser Cladding

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Experimental

2.1. Experimental Materials and Laser Cladding Process

2.2. Performance Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microscopic Morphology and Mechanical Properties

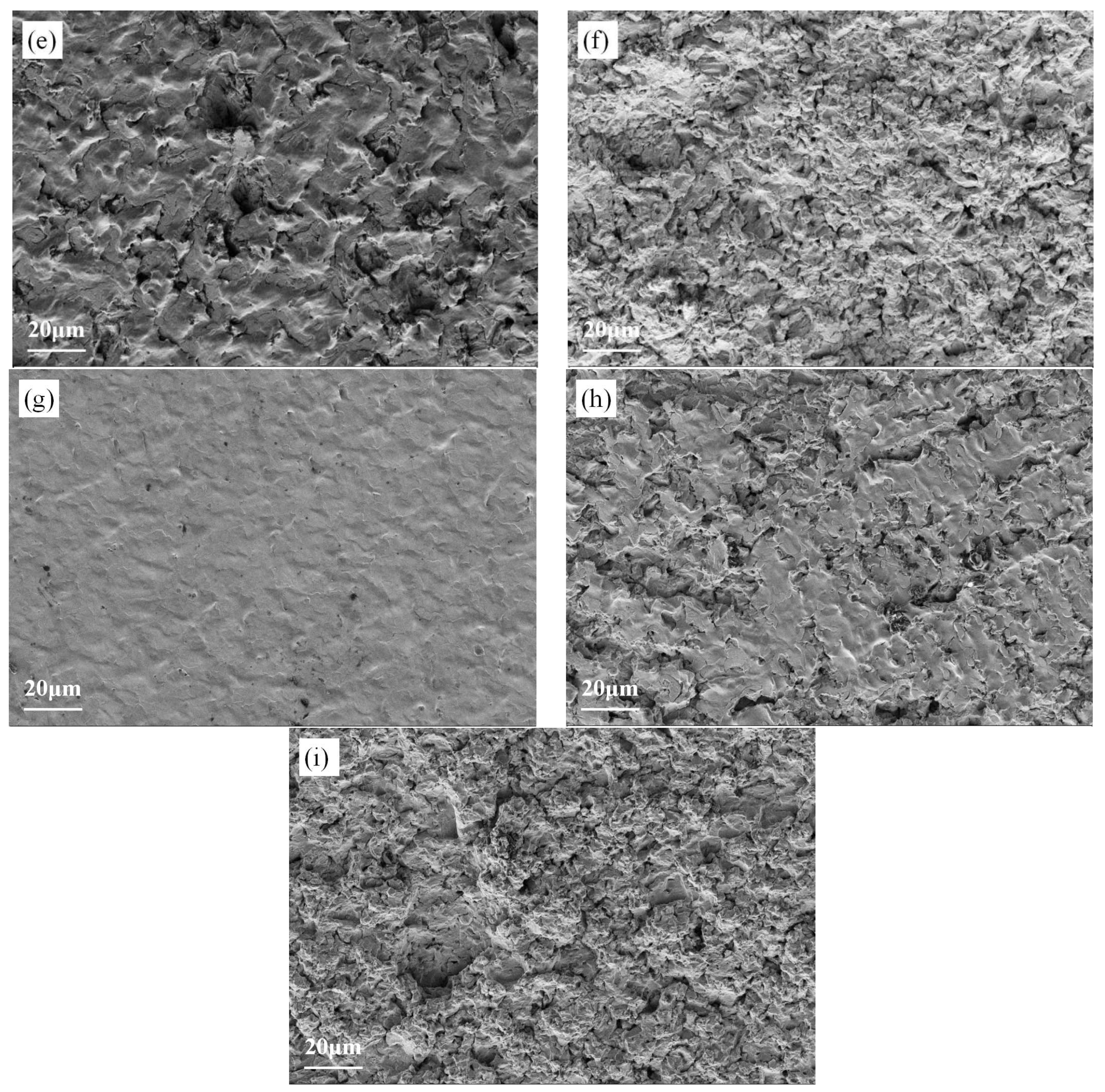

3.2. Friction Wear Performance

3.3. Cavitation Erosion Performance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, G.-C.; Li, J.-J.; Hu, N.; Tu, Q.-Y.; Hu, Z.-Q.; Hua, L. Cavitation erosion behavior of Fe50Mn30Co10Cr10 high entropy alloy coatings prepared by laser melting deposition. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2025, 35, 1570–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Wu, Y.; Hong, S.; Cheng, J.; Qiao, L.; Cheng, J.; Zhu, S. Effect of WC-10Co on cavitation erosion behaviors of AlCoCrFeNi coatings prepared by HVOF spraying. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 15121–15128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.G.; Wang, J.D.; Chen, D.R.; Liang, P. The role of passive potential in ultrasonic cavitation erosion of titanium in 1 M HCl solution. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2016, 29, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Cui, Z.; Li, Z.; Zhu, S.; Yang, X. Surface modification by gas nitriding for improving cavitation erosion resistance of CP-Ti. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 298, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhao, S.; Fu, J.; Xiao, S. Microstructure-Engineered CoCrFeNiTi HEA Coatings via HLC: Synergistic Enhancement of Wear and Corrosion Resistance. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Cui, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Dong, M.; Jin, G. Microstructure and wear resistance of laser cladded Ni-Cr-Co-Ti-V high-entropy alloy coating after laser remelting processing. Opt. Laser Technol. 2018, 99, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, F.; Yang, B.; Dong, S.; Zhao, H.; Xu, B.; Xu, F.; Liu, B.; He, P.; Feng, J. Effects of Fe-to-Co ratio on microstructure and mechanical properties of laser cladded FeCoCrBNiSi high-entropy alloy coatings. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 450, 538–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Liang, L.; Shan, Q.; Cai, A.; Du, J.; Huang, Q.; Liu, S.; Yang, X.; Tian, Y.; Wu, H. Effect of volumetric energy density on microstructure and tribological properties of FeCoNiCuAl high-entropy alloy produced by laser powder bed fusion. Virtual Phys. Prototyp. 2020, 15 (Suppl. S1), 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Han, T.-F.; Xiao, M.; Shen, Y.-F. Effect of process parameters on the microstructure and properties of laser-clad FeNiCoCrTi 0.5 high-entropy alloy coating. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2020, 27, 630–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Sun, X.; Chen, H.; Bai, X.; Wu, C. Effect of synergistic cavitation erosion-corrosion on cavitation damage of CoCrFeNiMn high entropy alloy layer by laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 472, 129940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Wang, R.; Wu, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Chen, H.; Tao, X. Effects of laser energy density on the resistance to wear and cavitation erosion of FeCrNiMnAl high entropy alloy coatings by laser cladding. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 329, 130122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Liu, Z.; Li, H.; Cao, X.; Guo, J.; Si, Y.; Cheng, J.; Yang, J. Enhanced corrosive-wear properties in AlCoCrFeNi2.1/TiC EHEA composite coatings prepared by laser cladding. Mater. Lett. 2026, 404, 139657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Luo, T.; Cheng, T.; Hu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, Z.; Lin, B.; Xiao, H. Microstructure and wear behavior of invar alloy surface strengthened by TiAl laser alloying and TiCN ceramics. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 520, 132977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gong, S.; Tang, M.; Song, M. Effect of laser cladding process on the microstructure and properties of high entropy alloys. Trans. China Weld. Inst. 2023, 44, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Cui, B.; Sun, Z.; Tong, Y. Effect of Laser Power on Microstructure and Tribological Performance of Ni60/WC Bionic Unit Fabricated via Laser Cladding. Metals 2025, 15, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Yang, A.; Chen, S.; Geng, L.; Guo, C.; Cui, L.; Zheng, B. Effect of Laser Power on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of High-Speed Laser-Cladded Coating on 27SiMn Steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Quan, X. Research on Microstructure and Wear Resistance of FeCoCrNiMnTix High Entropy Alloy Coatings Fabricated by Laser Cladding. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, T.; VishnuRameshkumar, R.; Selvakumar, M.; Mohanprasanth, A. Enhanced microstructural, corrosion properties and in vitro biocompatibility of high-entropy alloy coated over titanium by laser cladding. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 46, 112589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Si, L.; Dou, Z.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Liu, F. Cavitation Erosion Resistance of TiSiN/NiTiAlCoCrN Nanomultilayer Films with Different Modulation Periods. Coatings 2023, 13, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrifi-Alaoui, F.; Nassik, M.; Mahdouk, K.; Gachon, J. Enthalpies of formation of the Al–Ni intermetallic compounds. J. Alloys Compd. 2004, 364, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Wang, S.; Wang, G.; Gao, S.; Wang, L.; Yang, X. Microstructure evolution and frictional wear behavior of laser cladding FeCrCoNiMo0.5Wx high-entropy alloy coatings. Intermetallics 2023, 158, 107888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, S.; Wu, C.; Zhang, C.; Sun, X.; Bai, X. Electrochemical corrosion behavior in sulfuric acid solution and dry sliding friction and wear properties of laser-cladded CoCrFeNiNbx high entropy alloy coatings. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2023, 460, 129425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, Z.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Chen, P.; Shen, G.; Chen, C. Microstructure characteristic and tribological behavior of dual-phase hypo-eutectic high-entropy alloys Fe2Ni2CrV0.5Nb0.8 coating fabricated by laser cladding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2026, 519, 132970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kühlmann, J.; Kaiser, S.A. Single-Bubble Cavitation-Induced Pitting on Technical Alloys. Tribol. Lett. 2024, 72, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Number | Laser Power (W) | Scanning Speed (mm/s) | Powder Feed Rate (g/min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 3000 | 7 | 32 |

| S2 | 3200 | 7 | 32 |

| S3 | 3400 | 7 | 32 |

| Element/Number | 1# | 2# | 3# | 4# | 5# | 6# | 7# | 8# | 9# | 10# | 11# | 12# |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 3.91% | 4.86% | 3.87% | 3.91% | 3.27% | 3.05% | 3.98% | 3.78% | 3.04% | 3.66% | 3.48% | 3.96% |

| Ti | 9.20% | 2.13% | 2.65% | 10.02% | 10.36% | 9.09% | 3.87% | 3.32% | 12.70% | 10.05% | 2.96% | 3.10% |

| Cr | 24.09% | 37.56% | 36.44% | 23.18% | 25.03% | 27.21% | 36.40% | 37.49% | 22.63% | 24.35% | 37.09% | 37.38% |

| Co | 31.77% | 35.10% | 35.64% | 30.80% | 30.90% | 30.86% | 33.34% | 34.22% | 30.89% | 31.19% | 35.48% | 34.01% |

| Ni | 15.68% | 19.82% | 20.48% | 15.86% | 16.57% | 16.83% | 20.75% | 19.86% | 15.60% | 17.67% | 19.93% | 20.49% |

| Nb | 15.35% | 0.52% | 0.92% | 16.22% | 13.87% | 12.9%6 | 1.66% | 1.33% | 15.14% | 13.08% | 1.07% | 1.06% |

| Sample/Load (N) | 20 N |

|---|---|

| S1 | 1.41 × 10−4 mm3/N·m |

| S2 | 1.63 × 10−4 mm3/N·m |

| S3 | 1.49 × 10−4 mm3/N·m |

| 04Cr13Ni5Mo | 1.68 × 10−4 mm3/N·m |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, Z.; Yu, Y.; Chen, X.; Fu, L.; Wei, X.; Zhang, W.; Dong, Z.; Wang, M.; Wang, T.; Hui, X. Tailoring Microstructure and Properties of CoCrNiAlTiNb High-Entropy Alloy Coatings via Laser Power Control During Laser Cladding. Materials 2026, 19, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010005

Zhang Z, Yu Y, Chen X, Fu L, Wei X, Zhang W, Dong Z, Wang M, Wang T, Hui X. Tailoring Microstructure and Properties of CoCrNiAlTiNb High-Entropy Alloy Coatings via Laser Power Control During Laser Cladding. Materials. 2026; 19(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Zhe, Yue Yu, Xiaoming Chen, Li Fu, Xin Wei, Wenyuan Zhang, Zhao Dong, Mingming Wang, Tuo Wang, and Xidong Hui. 2026. "Tailoring Microstructure and Properties of CoCrNiAlTiNb High-Entropy Alloy Coatings via Laser Power Control During Laser Cladding" Materials 19, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010005

APA StyleZhang, Z., Yu, Y., Chen, X., Fu, L., Wei, X., Zhang, W., Dong, Z., Wang, M., Wang, T., & Hui, X. (2026). Tailoring Microstructure and Properties of CoCrNiAlTiNb High-Entropy Alloy Coatings via Laser Power Control During Laser Cladding. Materials, 19(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010005