Adequacy of Standard Models for Long-Term Behavior of Lightweight Concrete with Sintered Aggregate Under Cyclic Loading

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Development of Research on Standard Models

1.2. Long-Term Tests of Concrete on a New Type of Lightweight Sintered Aggregate

2. Materials and Methods—Research Program of Long-Term Properties of Concrete with Sintered Aggregate

2.1. Preparation of Concrete Mixtures

2.2. Types of Tests and Corresponding Samples

2.3. Types of Testing Machines

2.4. General Schedule for Testing Long-Term Deformation of Concrete Under Cyclic Loading

3. Test Results for Long-Term Properties

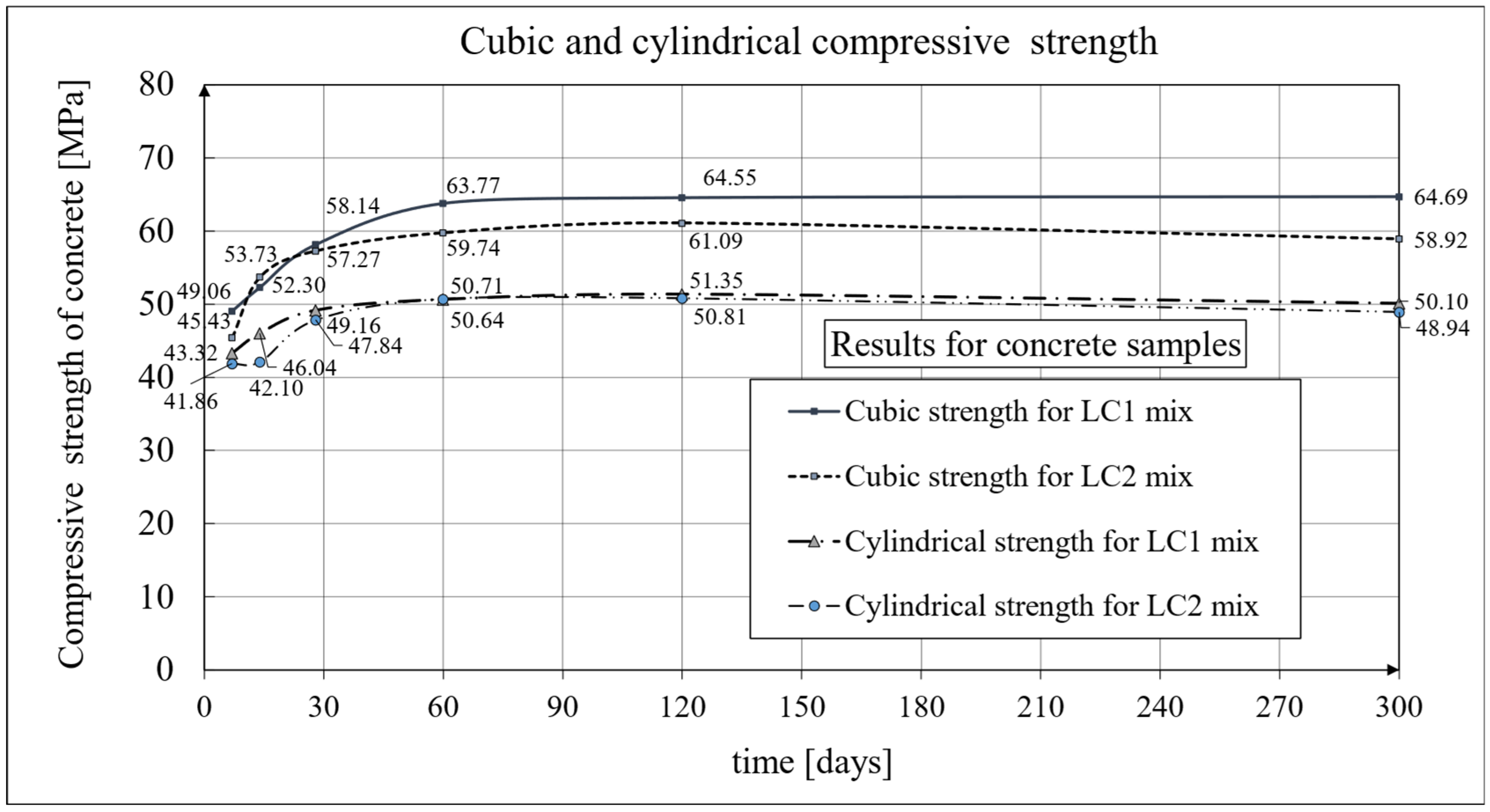

3.1. Test Results of Compressive Strength

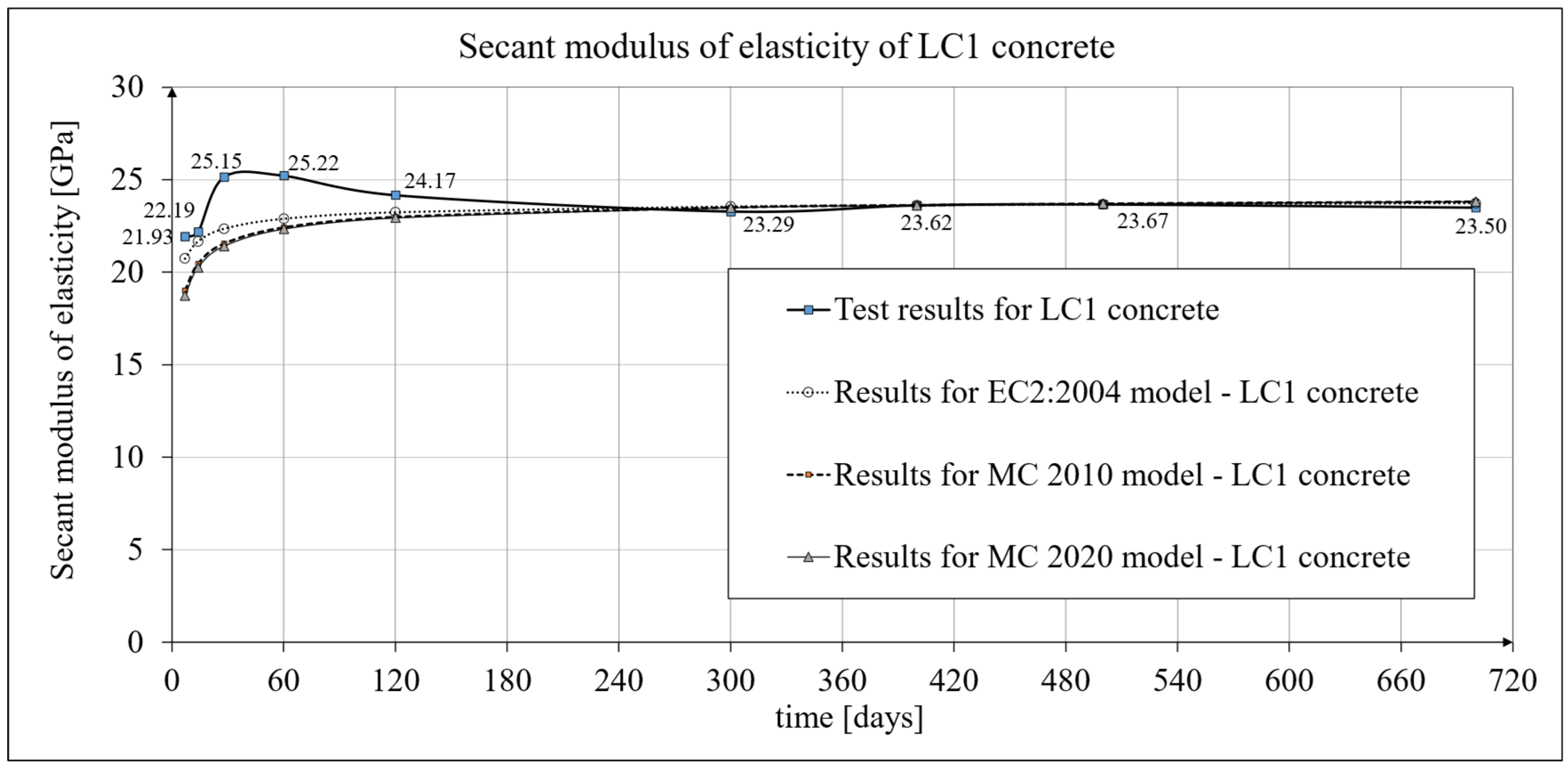

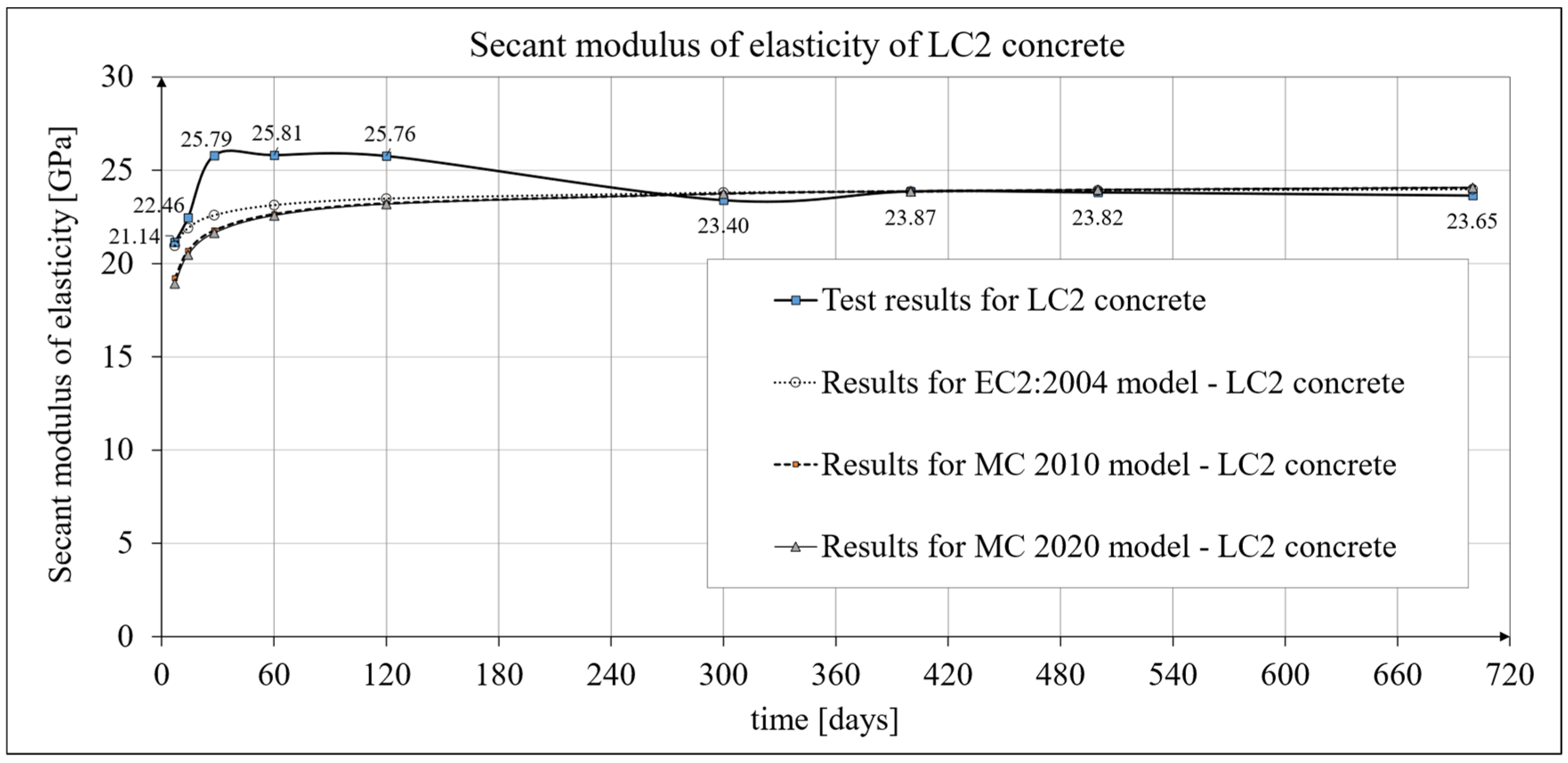

3.2. Results of Research and Analysis of Secant Modulus of Elasticity

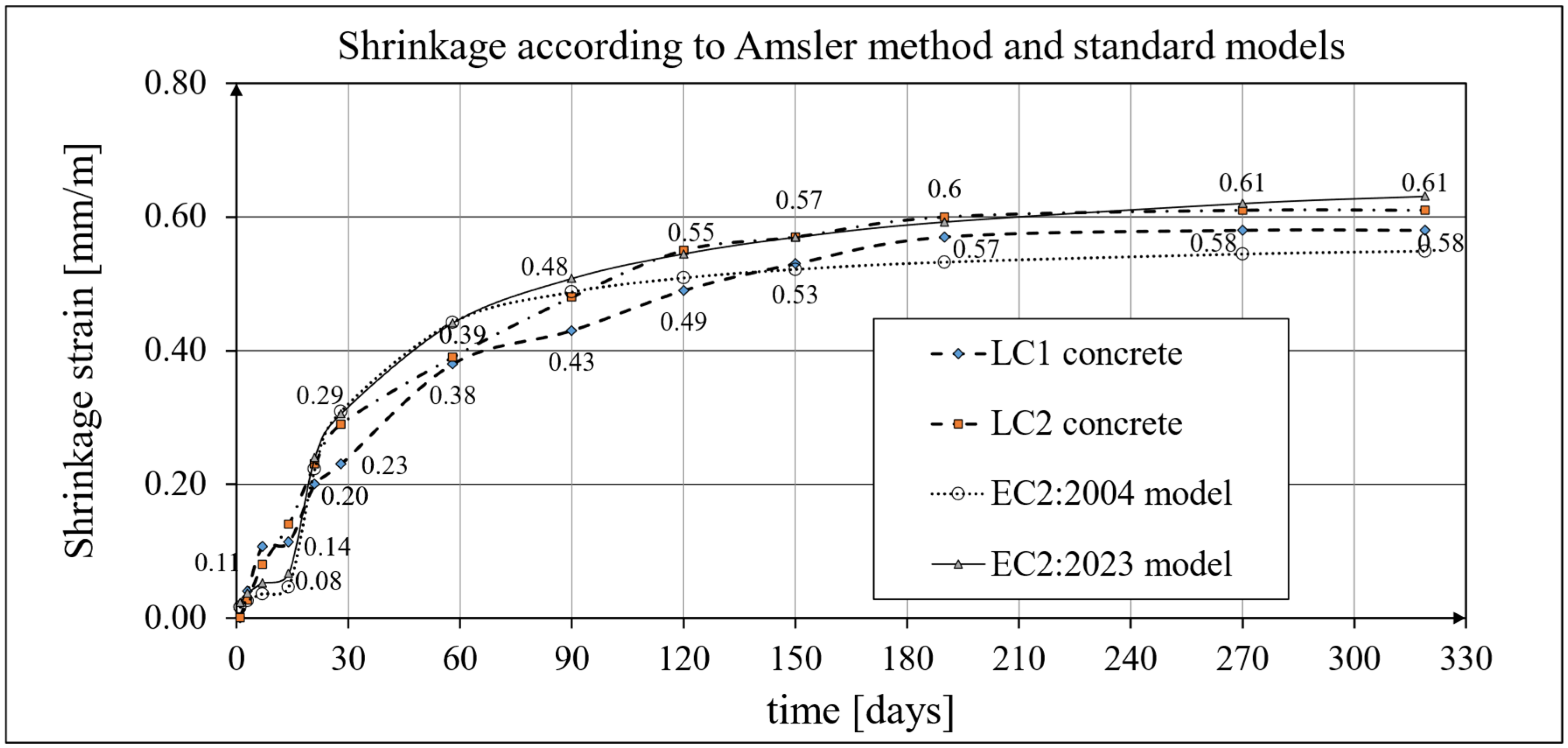

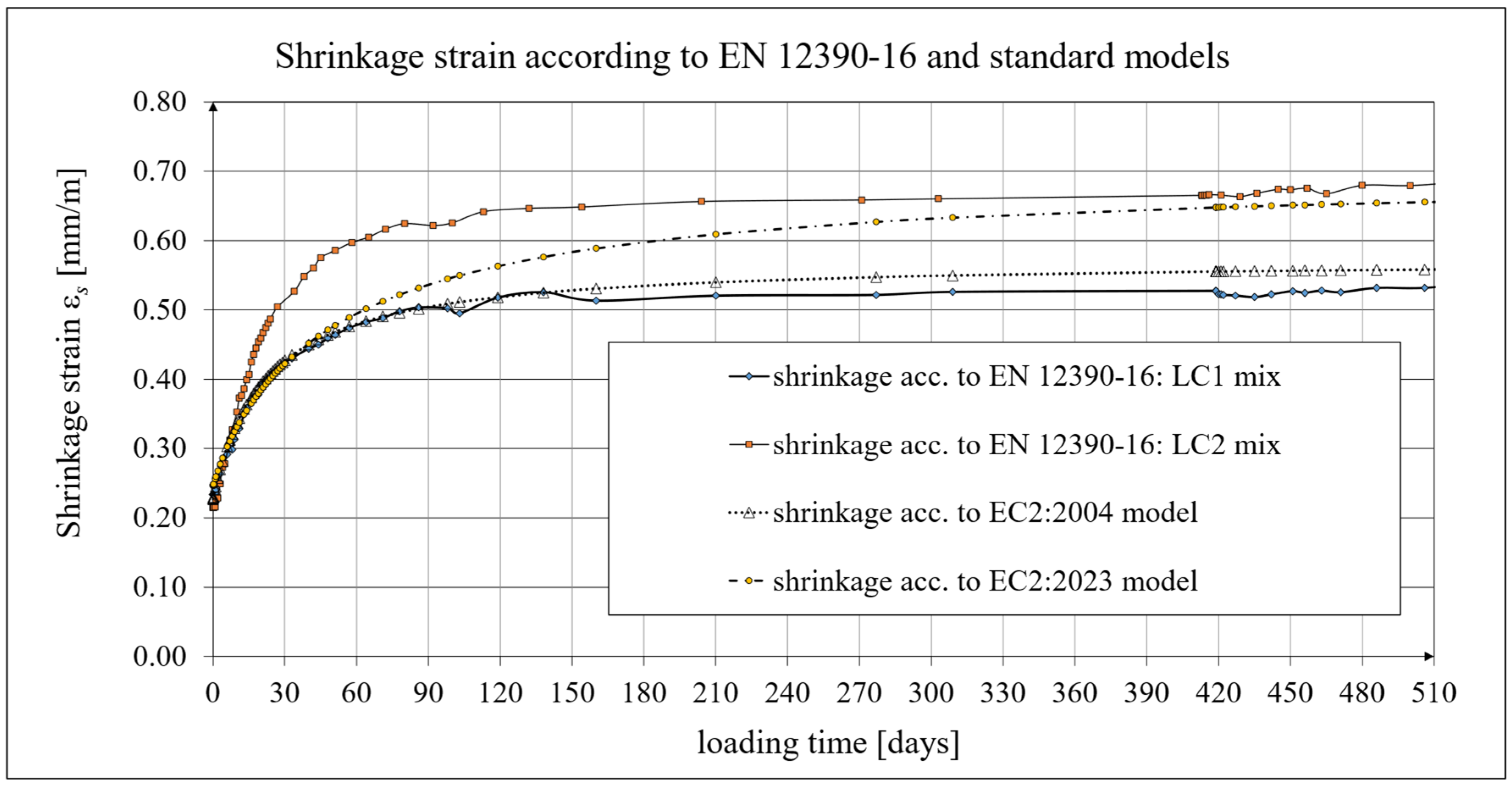

3.3. Results of Research and Analysis of Shrinkage Strain

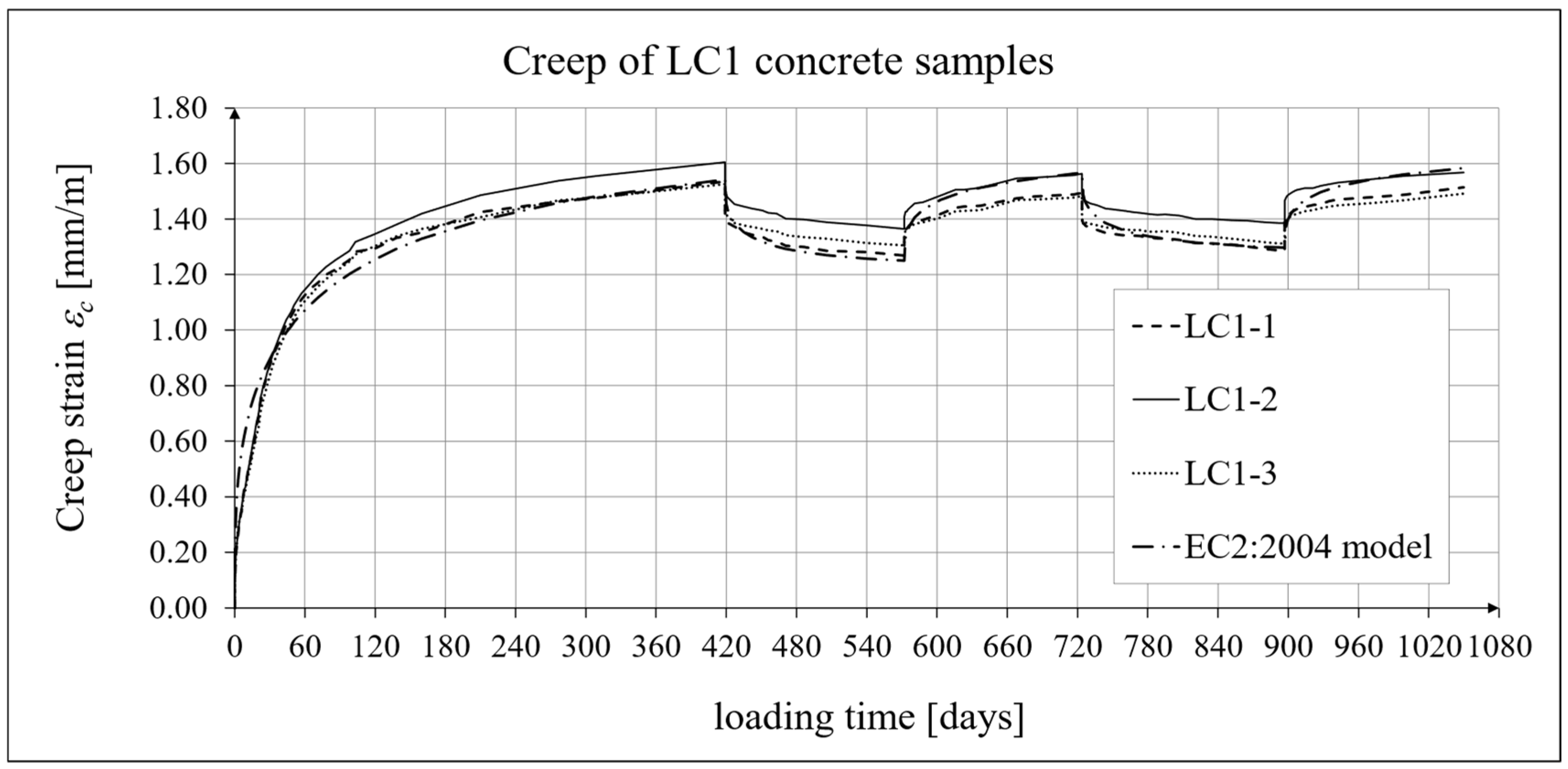

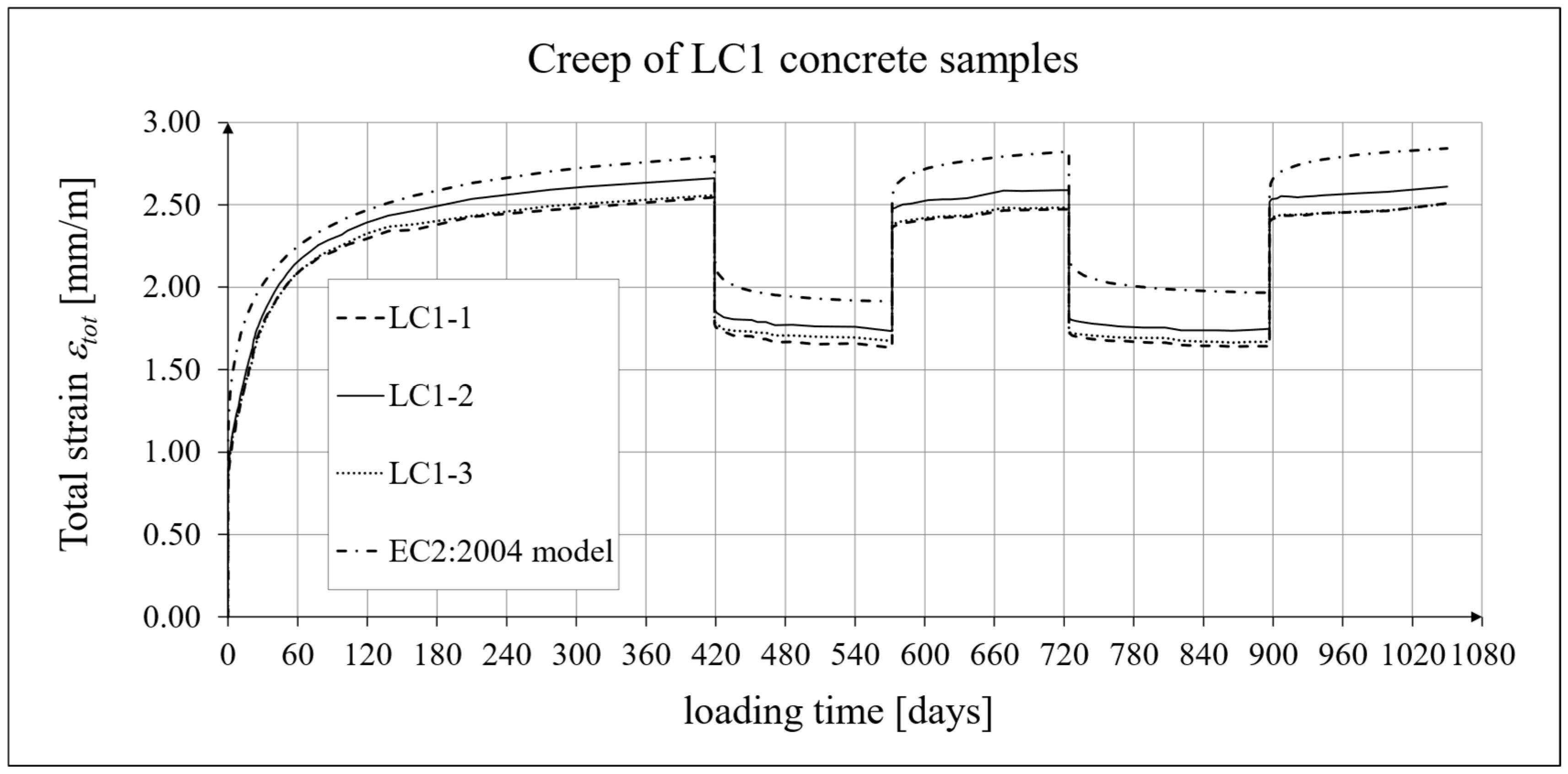

3.4. Results of Research and Analysis of Creep-Recovery Strain

4. Models of Long-Term Properties

4.1. Secant Modulus of Elasticity Models

- Ecm—

- the secant modulus of elasticity for concrete at the age of 28 days;

- βcc(t)—

- a coefficient that depends on the age of the concrete t and represents the evolution of concrete properties over time (see Equation (3.2) in EC2:2004 [66] and Equation (B.2) in EC2:2023 [67]; Equation (B.2) has a slightly more complex form than Formula (3.2) in EC2:2004 [66] and contains an additional parameter: tref);

- t—

- the age of the concrete in days;

- tref—

- a reference time for assessing the compressive strength of concrete, generally other than 28 days;

- s—

- a coefficient (see Equation (3.2) in EC2:2004 [66]) that depends on the type of cement (s = 0.25 for the considered cement of strength Class CEM 42.5 N (Class N));

- sc—

- a coefficient (see Equation (B.2) in EC2:2023 [67]) that depends on the concrete strength and its early development, i.e., on the type of cement (sc = 0.4 for a concrete strength of 35 MPa < fck < 60 MPa and the applied cement class CEM 42.5 N (Class CN)), where the considered lightweight concrete class LC 45/50 corresponds to a compressive strength flck = 45 MPa;

- n—

4.2. Shrinkage Models

- εcs(t)—

- the total shrinkage strain;

- εcd(t)—

- the shrinkage strain due to drying;

- εca(t)—

- the autogenous shrinkage strain.

- βds(t, ts)—

- the function describing the development of shrinkage strains due to drying as given by Equation (3.10) given in EC2:2004 [66];

- t—

- the age of the concrete at the moment in question, in days;

- ts—

- the age of the concrete (in days) at the beginning of drying (or swelling); this is usually at the end of curing;

- h0—

- Ac—

- the concrete cross-sectional area;

- u—

- the perimeter of the part of the cross-section exposed to drying;

- kh—

- αds1—a coefficient depending on the type of cement (see EC2:2004 Section 3.1.2(6) [66]);

- For the concrete under consideration αds1 = 4.0 was assumed for the cement class N;

- αds2—a coefficient depending on the type of cement;

- For the concrete under consideration αds2 = 0.012 was assumed for the cement class N;

- RH—the ambient relative humidity [%], RH0 = 100%.

4.3. Creep-Recovery Models—Parameterization and Modeling of Constitutive Relationships

- Integral equations of the hereditary law

- The hereditary model with concrete aging (and its changing modulus of elasticity);

- The elastic hereditary model;

- The concrete aging model;

- Standard and pre-standards models.

- φ0—

- the notional creep coefficient, which may be estimated from:φ0 = φRH · β(fcm) · β(t0).

- φRH—

- the coefficient accounting for the influence of relative humidity in accordance with the Equation (B.3) in EC2:2004 [66];

- β(fcm)—

- the coefficient accounting for the influence of the mean compressive concrete strength at 28 days in accordance with the Equation (B.4) in EC2:2004 [66];

- β(t0)—

- a factor to allow for the effect of concrete age at loading on the notional creep coefficient in accordance with the Equation (B.4) in EC2:2004 [66];

- h0—

- the nominal cross-sectional dimension in [mm] as in Section 4.2 (see Equations (B.3a/b) and (B.8a/b) in EC2:2004 [66]);

- βc (t, t0)—

- a coefficient describing the development of creep with time after loading, which may be estimated using Expression (B.7) in EC2:2004 [66];

- βH—

- α1, α2, and α3—

- are coefficients (see Equations (B.3b) and (B.8b) in EC2:2004 [66]) that consider the influence of the concrete strength (fcm).

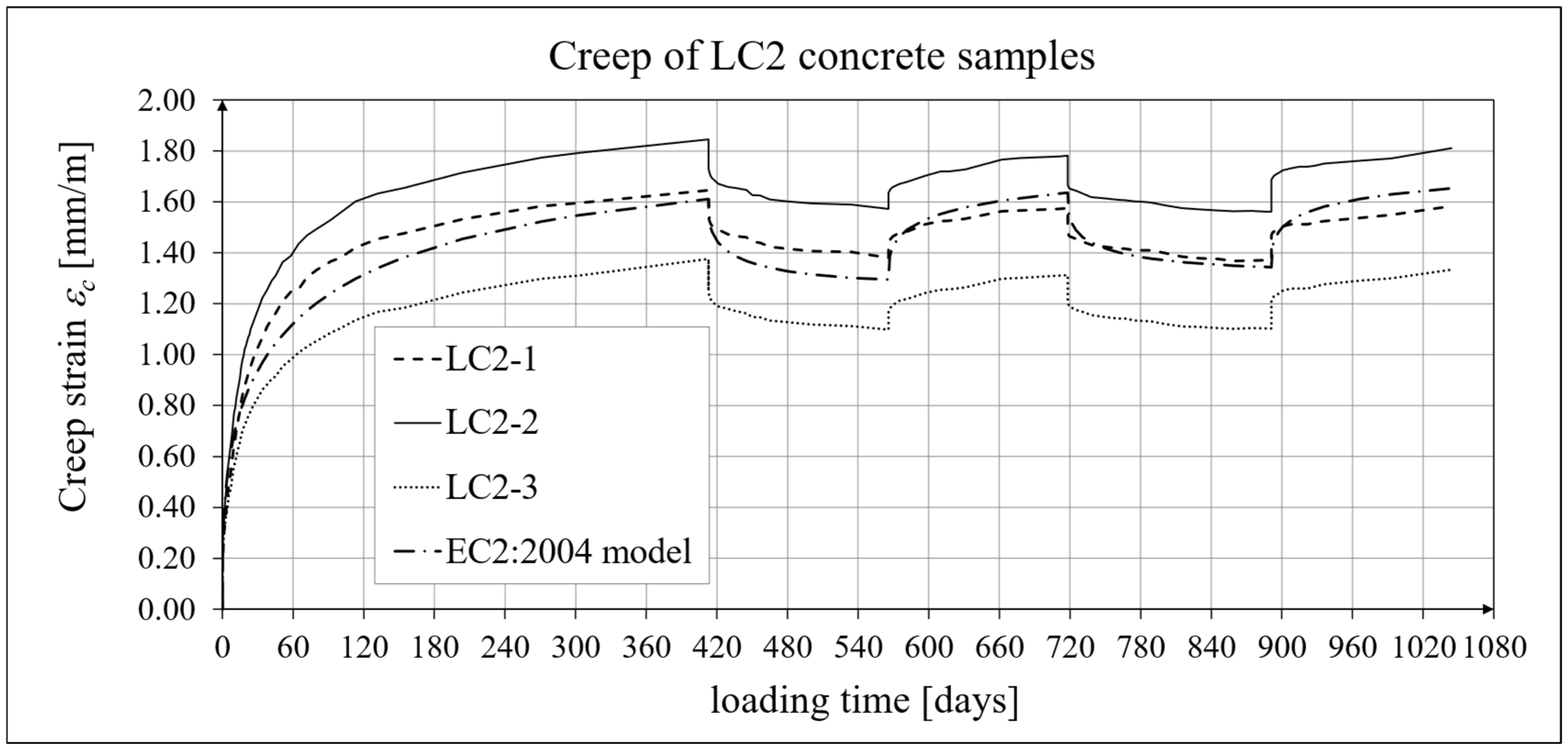

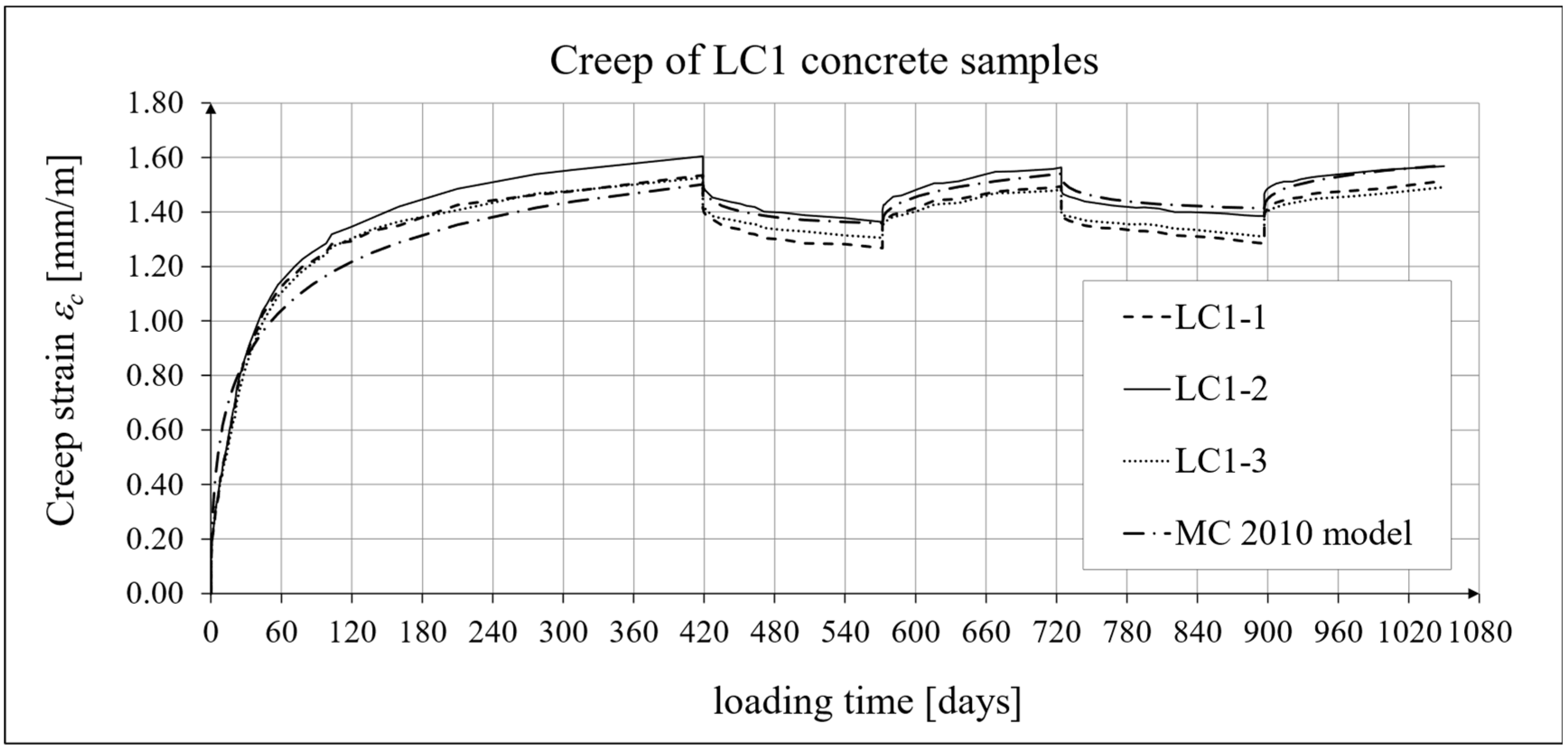

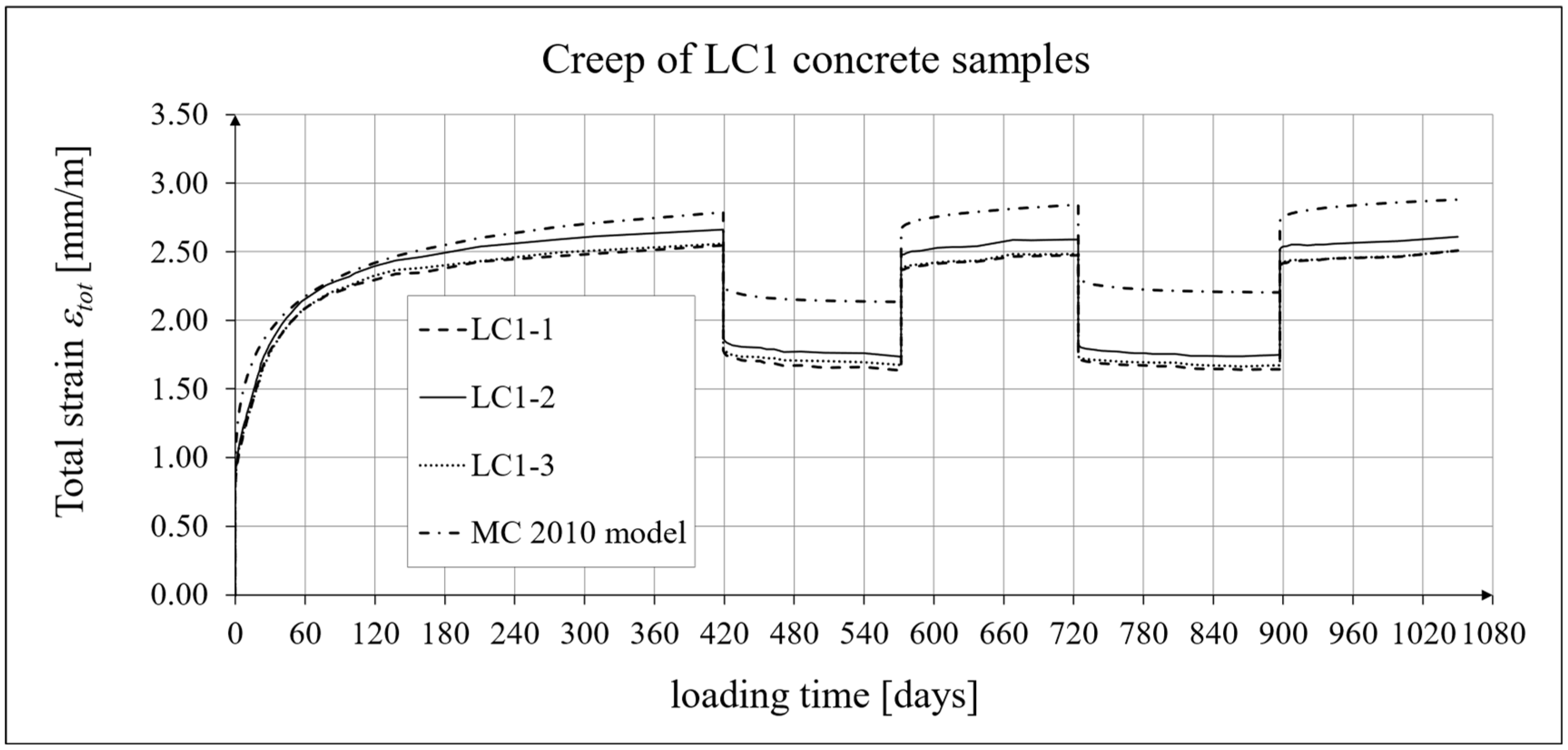

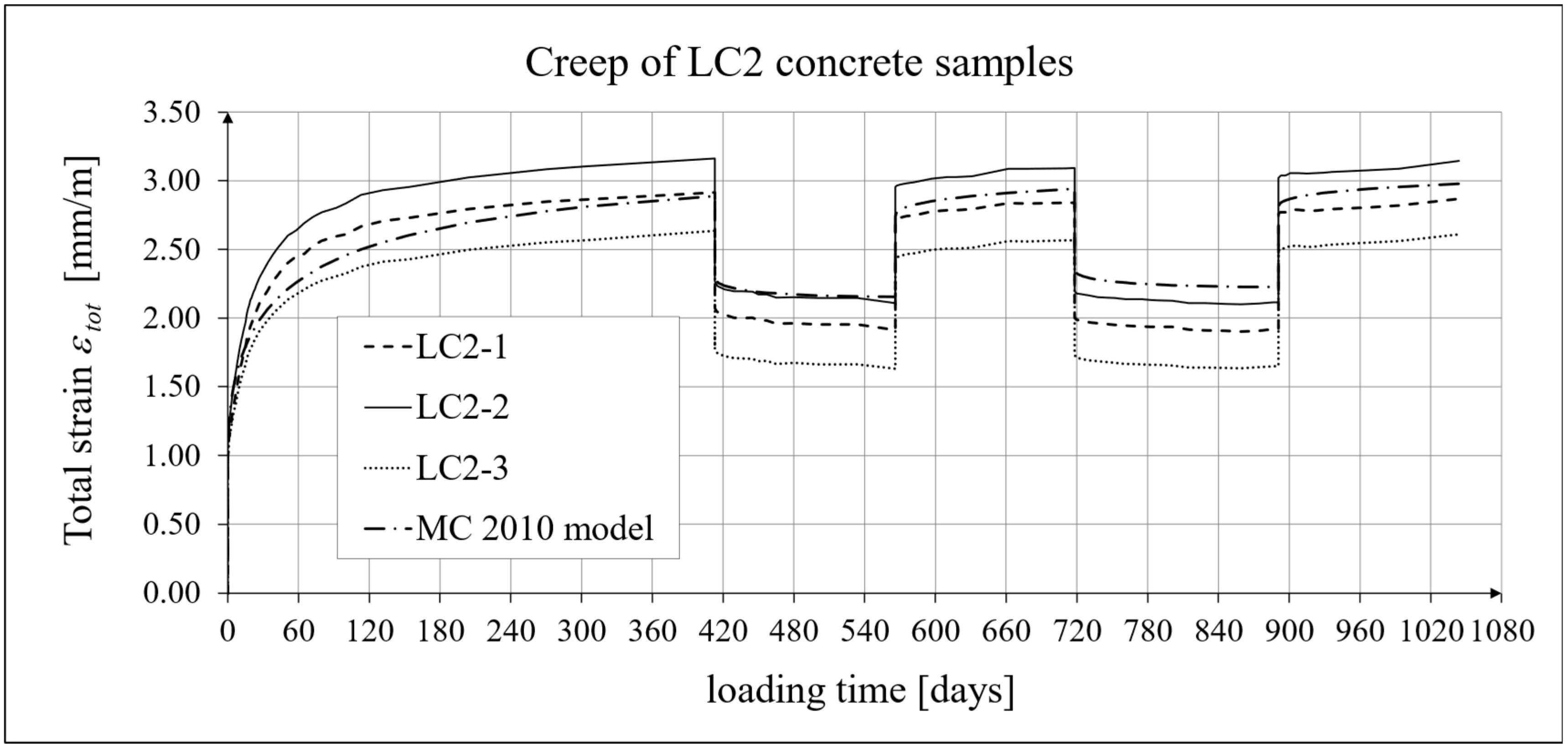

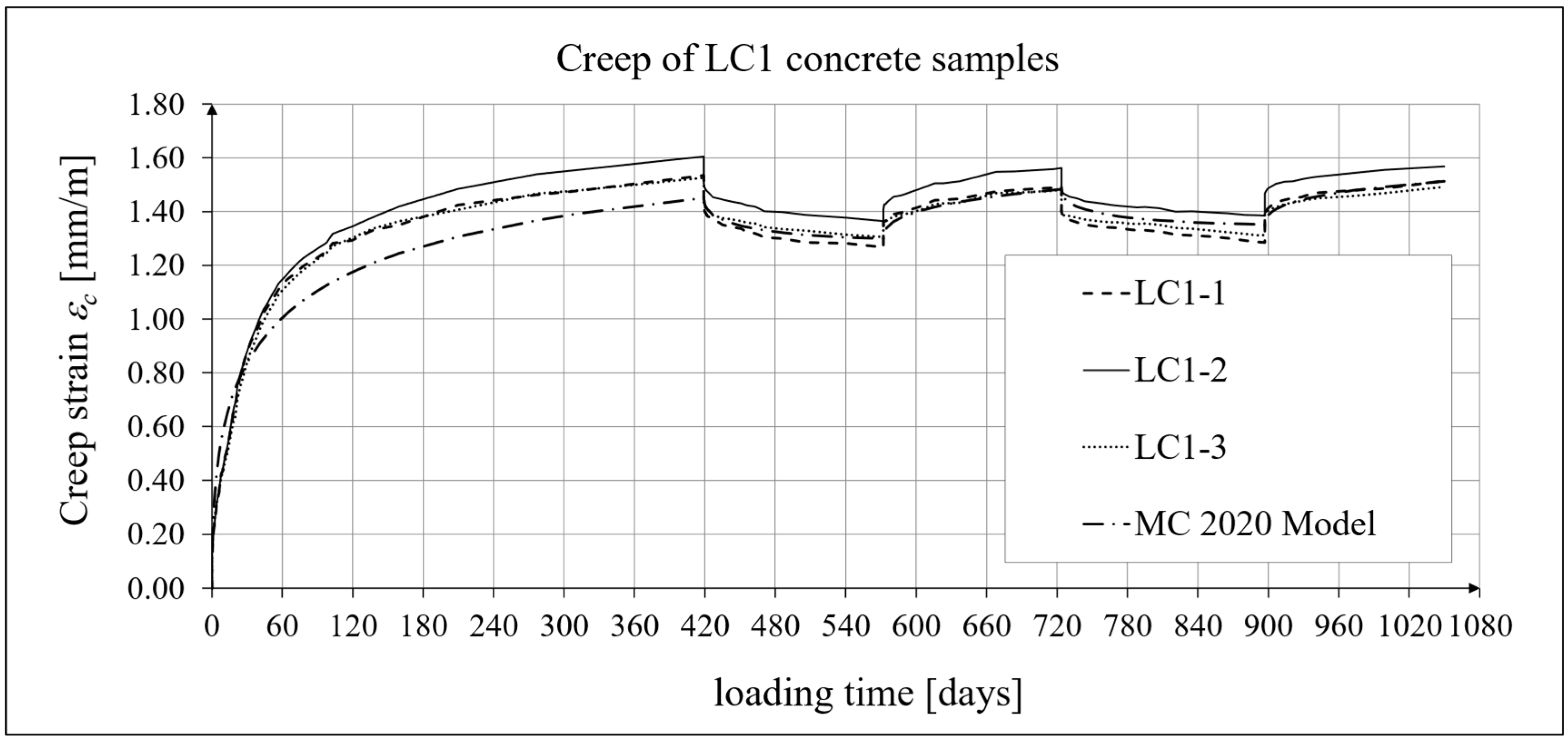

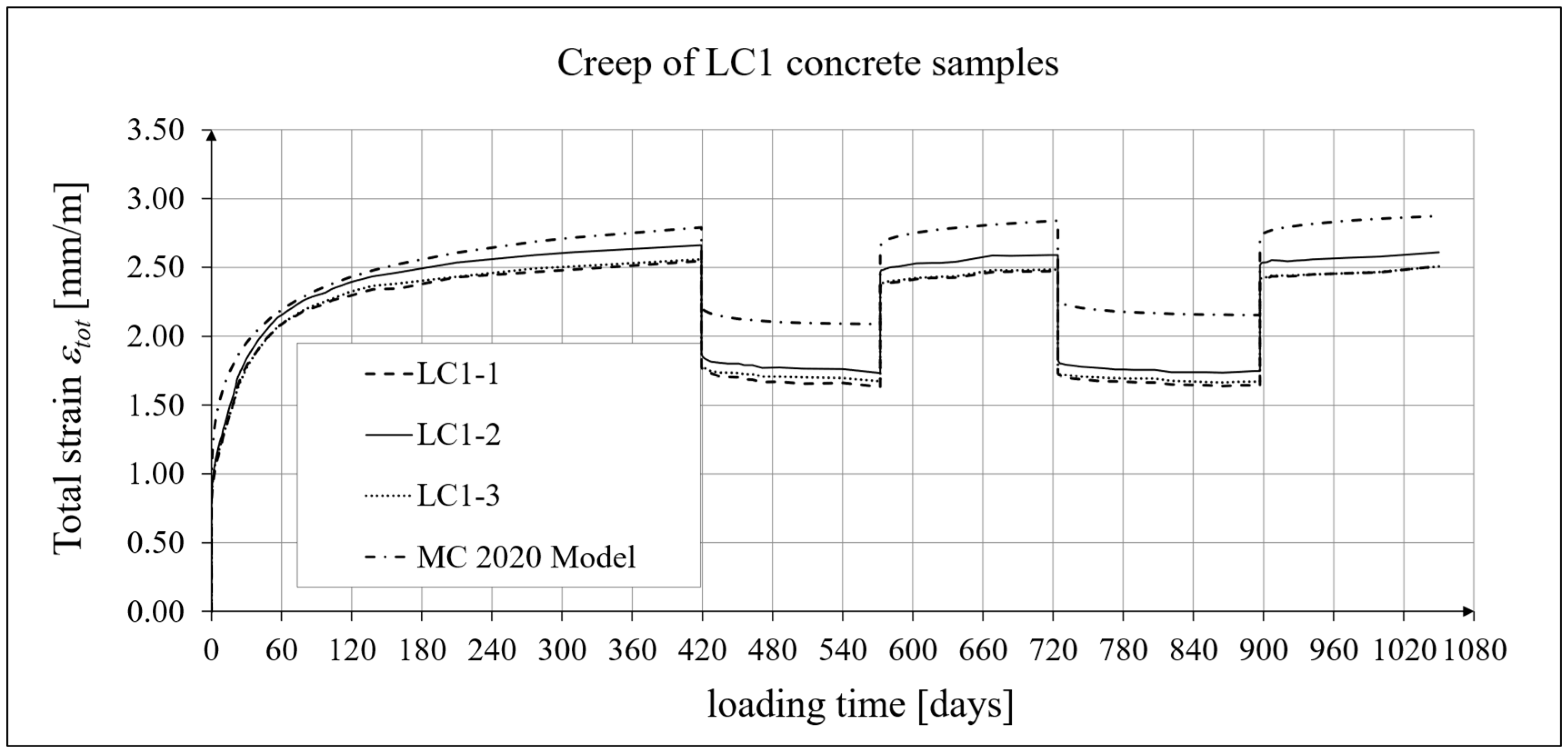

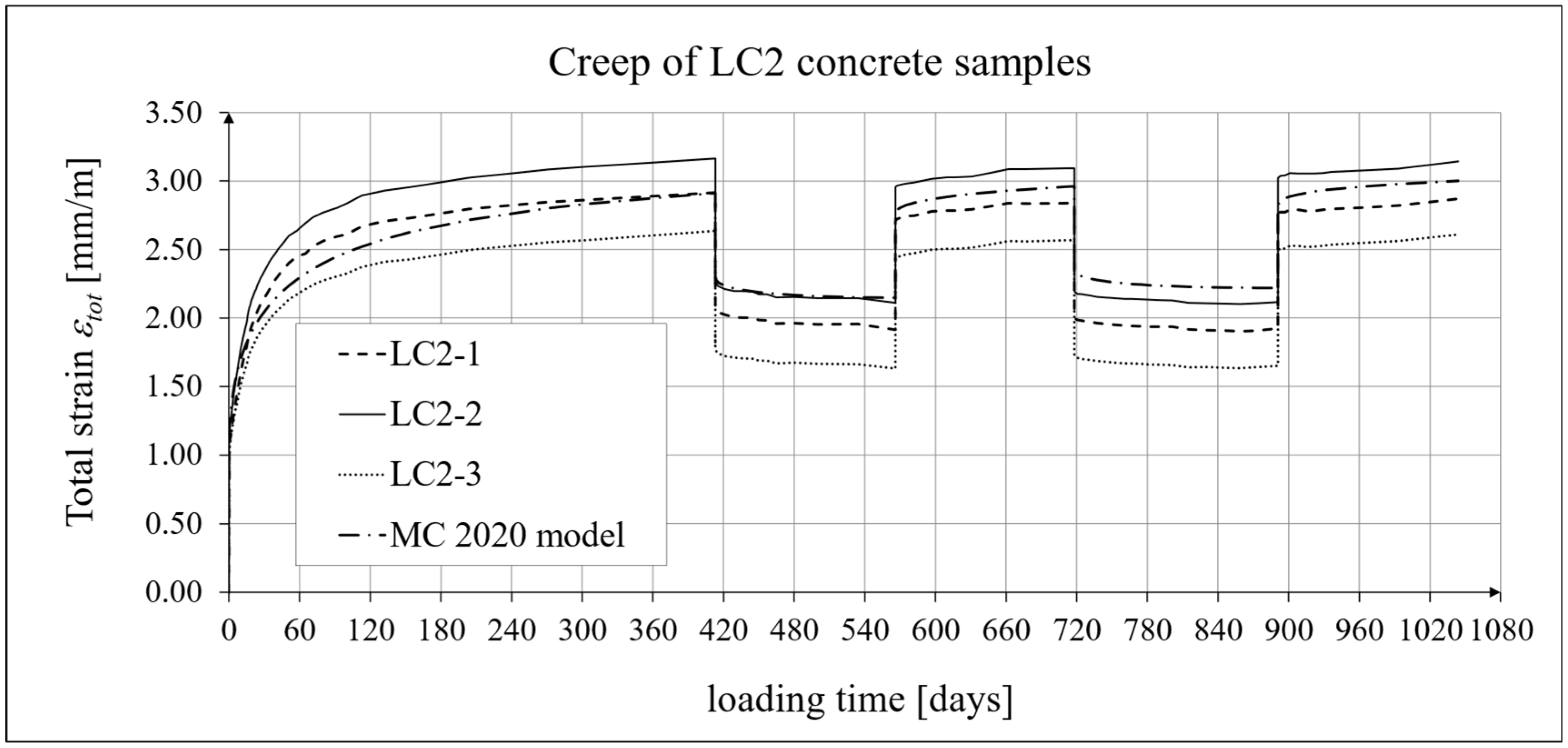

4.4. Comparison of Constitutive Relationships for Creep-Recovery Properties with Test Results

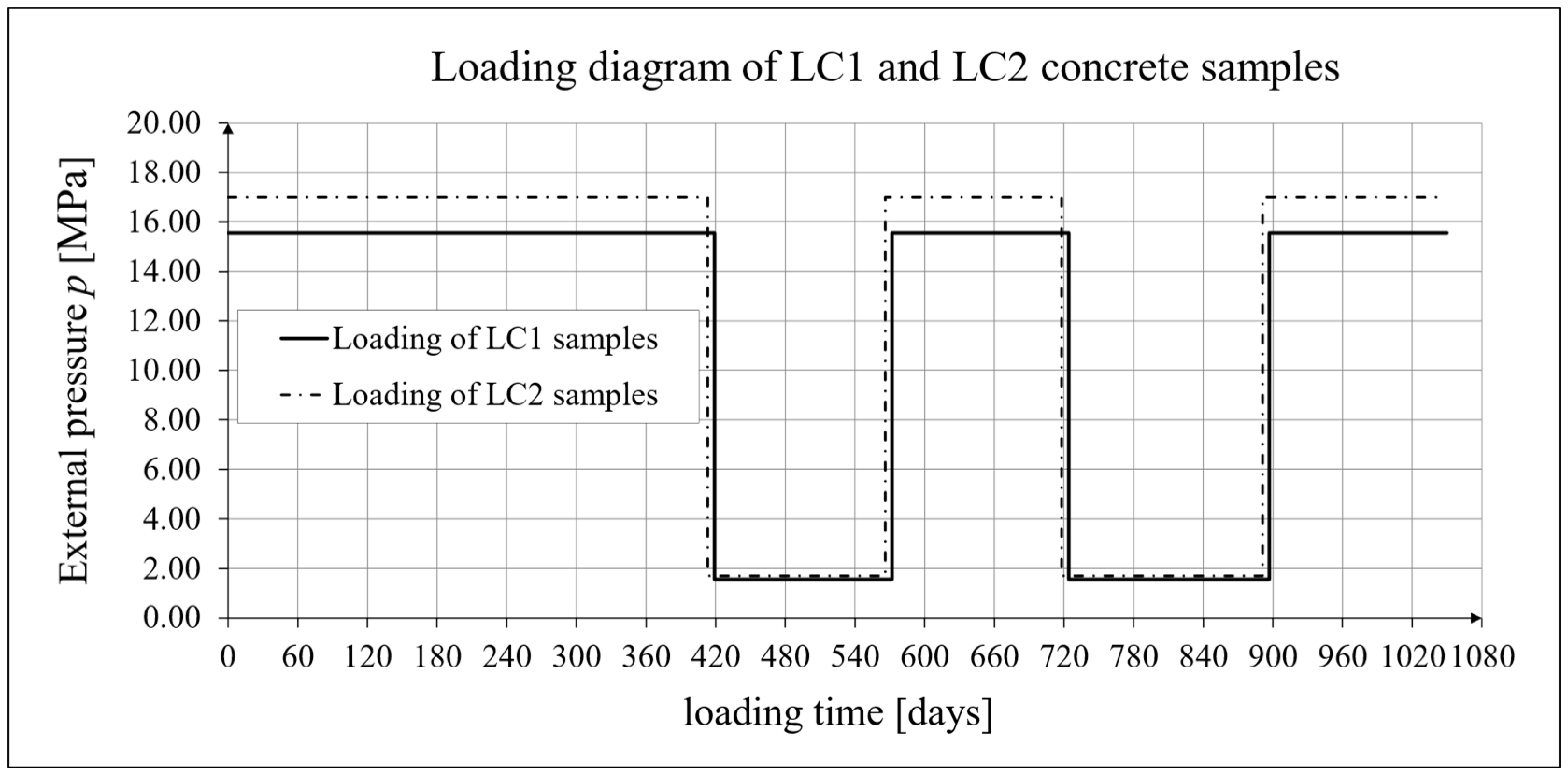

- For concrete made from the LC1 mix, the first loading phase lasted for 419 days at a stress of 15.55 MPa; the first unloading phase at a stress of 1.56 MPa lasted until 572 days after the first load was applied; the second loading phase at 15.55 MPa lasted until 724 days; the second unloading phase at 1.56 MPa lasted until 897 days; and the third loading phase at 15.55 MPa lasted until 1050 days after the first load was applied.

- For concrete made from the LC2 mix, the first loading phase lasted for 413 days at a stress of 16.96 MPa; the first unloading phase at a stress of 1.70 MPa lasted until 566 days after the first load was applied; the second loading phase at 16.96 MPa lasted until 718 days; the second unloading phase at 1.70 MPa lasted until 891 days; and the third loading phase at 16.96 MPa lasted until 1044 days after the first load was applied.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Conclusions for Experimental Results

- The average final creep coefficient values (after at least one year) of lightweight concrete with the examined sintered aggregate were similar of those of plain concrete of the same strength.

- Due to the low plastic strain of LWAC, a relatively low recovery magnitude (percentage of original creep) was observed compared to plain concrete.

- A limitation of the study was restricted access to creep testing machines—only two machines were available (although the ITB laboratory is equipped with more such devices), which limited the number of samples. Consequently, three samples were used to test the creep of LC1 concrete, and three samples were also used to test the creep of LC2 concrete.

- A limitation of the study was the relatively large scatter in the shrinkage results for the LC2 concrete mix, tested in accordance with the European standard, which was caused by variations in the moisture content of the aggregate used in the production of this concrete mix (the mix production took place outside the ITB laboratory).

- The stress changes did not increase the creep strains of the concrete under consideration subjected to cyclic loading, and the ratchetting phenomenon, attributable to very low plastic strain levels, was not detected.

- Further research is planned on concrete mixtures with lightweight aggregate containing additives that improve the concrete’s tensile strength, modulus of elasticity and frost resistance.

6.2. Conclusions for Model Calibration Results

- The development of creep-recovery strain for the examined LWAC is correctly modeled using the EC2:2004 [66] or EC2:2023 standard [67] models and the integral equations of the hereditary law, also provided in EC2:2023 [67] and MC 2020 [17], albeit with appropriate correction factors. In accordance with the requirements of EC2:2023 [67], these factors must be determined by minimizing the sum of squares of the differences between the model estimates and the experimental results. The necessity of using these factors results from the sensitivity of LWAC to the method of preparing the porous aggregate before concreting.

- Comparing the results of the analyses of total strain and creep strain obtained using the standard models, it can be concluded that the modifications introduced in the EC2:2023 [67] model compared to the EC2:2004 [66] model do not improve the approximation of the test results for the concrete type under consideration.

- Correcting the Boltzmann–Volterra superposition principle in its basic form (14) is unnecessary (provided the initial condition is properly formulated).

6.3. Direct Implications for Design Engineers

- The description of LWAC creep and shrinkage requires the use of the correction factors provided for in the EC2:2023 standard [67].

- Since the ratchetting phenomenon was not detected, the type of LWAC discussed can be used in building structures subjected to cyclically varying loads with long loading intervals.

- The research described in this paper confirmed the suitability of lightweight concrete with sintered ceramic aggregate derived from fly ash for use in cyclically loaded prestressed structures.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ITB | Instytut Techniki Budowlanej (Building Research Institute) |

| LSA | Lightweight Sintered Aggregate |

| LWAC | Lightweight Aggregate Concrete |

| IMiKB | Instytut Materiałów i Konstrukcji Budowlanych (Inst. of Building Mater. & Struct.) |

| W/C | Water/Cement Ratio |

| LC | Lightweight Concrete |

| CEM | Cement Class |

| CEB-FIP | the merger of CEB and FIP |

| CEB | Euro-International Committee for Concrete |

| FIP | International Federation for Prestressing |

| fib | International Federation for Concrete (the merger of CEB and FIP) |

| MC 2010 | Model Code 2010 |

| MC 2020 | Model Code 2020 |

| EC2:2004 | EN 1992-1-1:2004 Eurocode 2 |

| EC2:2023 | EN 1992-1-1:2023 Eurocode 2 |

References

- Lewiński, P.M.; Fedorczyk, Z.; Więch, P.; Zacharski, Ł. Short-Term and Long-Term Mechanical Properties of Lightweight Concrete with Sintered Aggregate. Materials 2025, 18, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whaley, C.P.; Neville, A.M. Non-elastic deformation of concrete under cyclic compression. Mag. Concr. Res. 1973, 25, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, A.M.; Dilger, W.H.; Brooks, J.J. Creep of Plain and Structural Concrete, 1st ed.; Construction Press: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Neville, A.M. Creep of Concrete: Plain, Reinforced and Prestressed, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Hirst, G.A.; Neville, A.M. Activation energy of creep of concrete under short-term static and cyclic stresses. Mag. Concr. Res. 1977, 29, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Panula, L. Practical prediction of time-dependent deformation of concrete (Part II: Basic creep). J. Mat. Struct. 1978, 11, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Panula, L. Practical prediction of time-dependent deformation of concrete (Part VI: Cyclic creep, nonlinearity and statistical scatter). J. Mat. Struct. 1979, 12, 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, J.J.; Forsyth, P. Relaxation of concrete and its relation to creep under uniaxial cyclic compression at various frequencies. Mag. Concr. Res. 1986, 38, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Kim, J.K. Improved prediction model for time-dependent deformations of concrete: Part 5—Cyclic load and cyclic humidity. Mater. Struct. 1992, 25, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Koh, C.G.; Ang, K.K.; Zhang, L. Effects of Repeated Loading on Creep Deflection of Reinforced Concrete Beams. Eng. Struct. 1997, 19, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Murphy, W.P. Creep and shrinkage prediction model for analysis and design of concrete structures—Model B3. Mater. Struct. 1995, 28, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, G.; Dehn, F.; Holschemacher, K.; Weiße, D. Determination of the bond creep coefficient for lightweight aggregate concrete (LWAC) under cyclic loading. In Challenges of Concrete Construction: Volume 6, Concrete for Extreme Conditions, Proceedings of the International Conference held at the University of Dundee, Scotland, UK, 9–11 September 2002; Thomas Telford Ltd.: London, UK, 2002; Volume 6, pp. 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Hubler, M.H. Theory of cyclic creep of concrete based on Paris law for fatigue growth of subcritical microcracks. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 2014, 63, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, B.; Oneschkow, N.; Podhajecky, A.L.; Lohaus, L.; Anders, S.; Haist, M. Comparative analysis of concrete behaviour under compressive creep and cyclic loading. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 153, 106409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Model Code 2010 First Complete Draft, Fib Bulletin 55, 1st ed.; DCC Siegmar Kästl e.K.: Ostfildern, Germany, 2010.

- Müller, H.S.; Anders, I.; Breiner, R.; Vogel, M. Concrete: Treatment of types and properties in fib Model Code 2010. Struct. Concr. 2013, 14, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fib Model Code for Concrete Structures (2020); CEB-FIP; Wiley: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2020.

- Bednář, J. Aggregate rebound effect on elastic and creep recovery of lightweight concrete. Cem. Concr. Res. 1979, 9, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, J.J. Prediction of Creep Recovery of Concrete from Creep in Tension and in Compression. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Leeds, Department of Civil Engineering, Leeds, UK, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, J.; Tu, N.; Liu, T.; Han, Z.; Tu, B.; Zhou, Y. Prediction models for creep and creep recovery of fly ash concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 428, 136398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Zheng, W.; Wang, Y.; Du, K.; Chang, W. Strain recovery model for concrete after compressive creep. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 199, 746–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Counto, U.J. The effect of the elastic modulus of the aggregate on the elastic modulus, creep and creep recovery of concrete. Mag. Concr. Res. 1964, 16, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dong, W.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, X. Effects of creep recovery on the fracture properties of concrete. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2020, 109, 102694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.Q.; Zhang, J.C.; Wang, Y.F.; Zou, R.F. Creep-recovery of normal strength and high strength concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 156, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Li, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, X.; Rong, L. Rate dependent short-term creep and creep recovery of normal concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 85, 108728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, A.M. Properties of Concrete, 5th ed.; Pearson Education Ltd.: Harlow, London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Z.; Si, R.; Jia, P.; Zhang, Y. Creep and relaxation responses of fly ash concrete: Linear and nonlinear cases. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, L.L.; Taerwe, L. Creep recovery of plain concrete and its mathematical modelling. Mag. Concr. Res. 1992, 44, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, W.; Yan, P. Measurement and modeling of creep property of high-strength concrete considering stress relaxation effect. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 56, 104726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.; Tailhan, J.L.; Le Maou, F. Creep strain versus residual strain of a concrete loaded under various levels of compressive stress. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 51, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Xie, T.; Ding, Y.; Fei, D.; Ding, S. Comparison of tensile and compressive creep of hydraulic concrete considering loading/unloading under unified test conditions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 286, 122763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; He, Y.; Wei, H. Study of creep test and creep model of hydraulic concrete subjected to cyclic loading. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilaire, A.; Benboudjema, F.; Darquennes, A.; Berthaud, Y.; Nahas, G. Modeling basic creep in concrete at early-age under compressive and tensile loading. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2014, 269, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, R.Y.; Huang, G.X.; Yi, B.R. Tensile creep and compressive creep of concrete with fly ash. Water Res. Hydropower Eng. 1986, 12, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, G.M.; Kanstad, T.; Bjøntegaard, Ø.; Sellevold, E.J. Tensile and compressive creep deformations of hardening concrete containing mineral additives. Mater. Struct. 2013, 46, 1167–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.G.; Park, Y.S.; Lee, Y.H. Comparison of Concrete Creep in Compression, Tension, and Bending under Drying Condition. Materials 2019, 12, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klausen, A.E.; Kanstad, T.; Bjøntegaard, Ø.; Sellevold, E. Comparison of tensile and compressive creep of fly ash concretes in the hardening phase. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 95, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranaivomanana, N.; Multon, S.; Turatsinze, A. Basic creep of concrete under compression, tension and bending. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 38, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.; Charron, J.P.; Bastien-Masse, M.; Tailhan, J.L.; Le Maou, F.; Ramanich, S. Tensile basic creep versus compressive basic creep at early ages: Comparison between normal strength concrete and a very high strength fibre reinforced concrete. Mater. Struct. 2014, 47, 1773–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, P.; Tailhan, J.L.; Le Maou, F. Comparison of concrete creep in tension and in compression: Influence of concrete age at loading and drying conditions. Cem. Concr. Res. 2013, 51, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wu, Z.; Huang, J.; Liang, S. Comparison of compressive, tensile, and flexural creep of early-age concretes under sealed and drying conditions. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, D.S. Mechanical and Deformational Properties, and Shrinkage Cracking Behaviour of Lightweight Concretes. Ph.D. Thesis, National University of Singapore, Singapore, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, T.Y.; Sham, F.C.; Cui, H.Z.; Tang, W.C.P. Study of short term shrinkage and creep of lightweight concrete. Mater. Res. Innov. 2008, 12, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneti, S.B.; Tam, C.T.; Tamilselvan, T.; Kannan, V.; Kong, K.H.; Islam, M.R. Shrinkage Cracking Potential of Lightweight Aggregate Concrete. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2024, 2779, 012067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montazerian, A.; Nili, M.; Haghighat, N.; Loghmani, N. Experimental and simplified visual study to clarify the role of aggregate-paste interface on the early age shrinkage and creep of high-performance concrete. Asian J. Civ. Eng. 2021, 22, 1461–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Jiang, J.; Jiao, Y.; Shen, J.; Jiang, G. Early-age tensile creep and cracking potential of concrete internally cured with pre-wetted lightweight aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 135, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.F.; Fang, C.; Kuang, W.Q.; Li, D.W.; Han, N.X.; Xing, F. Experimental study on early cracking sensitivity of lightweight aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 136, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo-Cabo, A.; Lázaro, C.; López-Gayarre, F.; Serrano-López, M.A.; Serna, P.; Castaño-Tabares, J.O. Creep and shrinkage of recycled aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 2545–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, A.; Lázaro, C.; Gayarre, F.L.; Serrano, M.A.; López-Colina, C. Long term deformations by creep and shrinkage in recycled aggregate concrete. Mater. Struct. 2010, 43, 1147–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighat, N.; Nili, M.; Montazerian, A.; Yousef, R. Proposing an Image Analysis to Study the Effect of Lightweight Aggregate on Shrinkage and Creep of Concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. Mater. 2020, 9, 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havlásek, P. Creep and Shrinkage of Concrete Subjected to Variable Environmental Conditions. Ph.D. Thesis, Czech Technical University in Prague, Prague, Czechia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nukah, P.D.; Abbey, S.J.; Booth, C.A.; Oti, J. Evaluation of the structural performance of low carbon concrete. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukah, P.D.; Abbey, S.J.; Booth, C.A.; Oti, J. Development of low carbon concrete and prospective of geopolymer concrete using lightweight coarse aggregate and cement replacement materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 428, 136295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendling, A.; Sadhasivam, K.; Floyd, R.W. Creep and shrinkage of lightweight self-consolidating concrete for prestressed members. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 167, 205–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, Y.Z.; Chen, C.Y.; Ji, T. Effect of shale ceramsite type on the tensile creep of lightweight aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 46, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Ji, T.; Easa, S.M.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, Z. Tensile basic creep behavior of lightweight aggregate concrete reinforced with steel fiber. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 200, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, K.-S.; Liu, X.; Liew, J.-Y.; Zhang, M.-H. Experimental study on creep and shrinkage of high-performance ultralightweight cement composite of 60 MPa. Struct. Eng. Mech. 2014, 50, 635–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Yang, H.; Xu, X.; Lin, Z.; Lo, T.Y. Effect of cured time on creep of lightweight aggregate concrete. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on the Durability of Concrete Structures, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China, 30 June–1 July 2016; pp. 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lye, C.Q.; Dhir, R.K.; Ghataora, G.S. Estimation models for creep and shrinkage of concrete made with natural, recycled and secondary aggregates. Mag. Concr. Res. 2022, 74, 392–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Singh, S.B.; Barai, S.V.; Singh, A.; Ojha, P.N. Experimental determination of creep coefficients for sintered flyash lightweight aggregate based concrete and verification with creep models. Res. Eng. Struct. Mater. 2024, 11, 1179–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojewódzki, W.; Jemioło, S.; Lewiński, P.M.; Szwed, A. On the Constitutive Relationships Modelling the Mechanical Properties of Concrete, 1st ed.; Oficyna Wydawnicza PW, Prace Nauk., Bud. 128: Warszawa, Poland, 1995. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Biliszczuk, J. Rheological Redistribution of the Stress State in Non-Homogenous Isostatic Concrete Structures, 1st ed.; PWN, Studia z Zakr. Inż. 21: Warszawa, Poland, 1982. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Biliszczuk, J. Concrete—A Material for Bridge Building, 1st ed.; Science Papers of the Institute of Civil Engineers of the Technology University of Wrocław, 32, Monographs, 10; Technology University of Wrocław Publishing House: Wrocław, Poland, 1986. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Mitzel, A. Rheology of Concrete, 1st ed.; Arkady: Warszawa, Poland, 1972. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Brunarski, L. Fundamentals of Rheology of Concrete Structures; Scientific Studies, Monographs, ITB: Warszawa, Poland, 2019. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- EN 1992-1-1:2004; Eurocode 2: Design of Concrete Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules and Rules for Buildings. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2004.

- EN 1992-1-1:2023; Eurocode 2—Design of Concrete Structures—Part 1-1: General Rules, Rules for Buildings, Bridges and Civil Engineering Structures. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2023.

- Łuczaj, K.; Urbańska, P. Certyd—New lightweight high-strength sintered aggregate. Mater. Bud. 2015, 12, 42–45. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domagała, L. Structural Lightweight Aggregate Concrete, Monografia 462, 1st ed.; Cracow University of Technology Publishing House: Cracow, Poland, 2014; Available online: https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/redo/resources/25702/file/suwFiles/DomagalaL_KonstrukcyjneBetony.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2025). (In Polish)

- Mieszczak, M. Application of lightweight concrete to construction, especially for prestressed floor slabs. Tech. Issues 2016, 4, 55–61. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Szydłowski, R.; Mieszczak, M. Study of application of lightweight aggregate concrete to construct post-tensioned long-span slabs. Procedia Eng. 2017, 172, 1077–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieszczak, M.; Szydłowski, R. Lightweight concrete in prestressed structures. Builder 2017, 240, 90–93. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Mieszczak, M.; Domagała, L. Lightweight Aggregate Concrete as an Alternative for Dense Concrete in Post-Tensioned Concrete Slab. Mater. Sci. Forum. 2018, 926, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieszczak, M.; Szydłowski, R. Light aggregate concrete research for the construction of large span slab. In Proceedings of the Konf. Nauk.-Techn. Konstrukcje Sprężone, Kraków, 18–20 Kwietnia 2018, 1st ed.; Derkowski, W., Gwoździewicz, P., Pańtak, M., Politalski, W., Seruga, A., Zych, M., Eds.; Cracow University of Technology Publishing House: Cracow, Poland, 2018; pp. 147–150. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Szydłowski, R.; Kurzyniec, K. Influence of bulk density of lightweight aggregate concrete on strength and performance parameters of a slab-and-beam floor. Inżynieria I Bud. 2018, 74, 162–164. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Szydłowski, R. Concrete properties for long-span post-tensioned slabs. Mater. Sci. Forum 2018, 926, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szydłowski, R.S.; Łabuzek, B. Experimental Evaluation of Shrinkage, Creep and Prestress Losses in Lightweight Aggregate Concrete with Sintered Fly Ash. Materials 2021, 14, 3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seruga, A.; Szydłowski, R. Bond Strength of Lightweight Aggregate Concrete to the Plain Seven-Wire Non-pretensioned Steel Strand. In Proceedings of the Building for the Future: Durable, Sustainable, Resilient, Istanbul, Turkey, 5–7 June 2023, 1st ed.; Ilki, A., Çavunt, D., Çavunt, Y.S., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 1, pp. 1742–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szydłowski, R.; Mieszczak, M. Analysis of application of lightweight aggregate concrete to construct post-tensioned long-span slabs. Inżynieria I Bud. 2018, 74, 68–72. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, S.; Berntsson, L. Lightweight Aggregate Concrete. Science, Technology, and Applications, 1st ed.; Noyes Publications; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rogowska, A.M.; Lewiński, P.M. Mechanical properties of lightweight concrete with sintered aggregate. MATEC Web Conf. 2020, 323, 01005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogowska, A.; Lewiński, P. Structural lightweight concrete with sintered aggregate as a material for strengthening constructions. In XVI Konferencja Naukowo-Techniczna: Warsztat Pracy Rzeczoznawcy Budowlanego, Kielce-Cedzyna, Poland, 26–28 October 2020, 1st ed.; Runkiewicz, L., Goszczyńska, B., Eds.; Zarząd Główny Polskiego Związku Inżynierów i Techników Budownictwa (Zarząd Gł. PZITB): Warszawa, Poland, 2020; pp. 483–491. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- EN 12390-7:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 7: Density of Hardened Concrete. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- EN 12390-13:2013; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 13: Determination of Secant Modulus of Elasticity in Compression. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2013.

- EN 12390-3:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 3: Compressive Strength of Test Specimens. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Brunarski, L. Testing of mechanical properties of concrete on samples made in moulds. In Instrukcja 194/98; ITB: Warszawa, Poland, 1998. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- EN 12390-6:2009; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 6: Tensile Splitting Strength of Test Specimens. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2009.

- EN 12390-5:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 5: Flexural Strength of Test Specimens. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- PN-B-06714-23:1984; Mineral Aggregates—Testing—Determination of Volume Changes by Amsler Method. PKN: Warszawa, Poland, 1984. (In Polish)

- EN 12390-16:2019; Testing Hardened Concrete—Part 16: Determination of the Shrinkage of Concrete. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- EN 1355:1996; Determination of Creep Strains Under Compression of Autoclaved Aerated Concrete or Lightweight Aggregate Concrete with Open Structure. CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 1996.

- Lopez, M.; Kahn, L.F.; Kurtis, K.E. Effect of internally stored water on creep of high-performance concrete. ACI Mater. J. 2008, 105, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, P.; Ulm, F.-J. Creep and shrinkage of concrete: Physical origins and practical measurements. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2001, 203, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glanville, W.H. Studies in Reinforced Concrete. Part II Shrinkage Stresses, 1st ed.; Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, Building Research & Technology Paper 11; HM Stationery Office: London, UK, 1930. [Google Scholar]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Jirásek, M. Creep and Hygrothermal Effects in Concrete Structures, 1st ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Häussler-Combe, U. Computational Methods for Reinforced Concrete Structures, 1st ed.; Ernst & Sohn: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bažant, Z.P. Numerical determination of long-range stress history from strain history in concrete. Mater. Struct. 1972, 5, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jirásek, M.; Bažant, Z.P. Inelastic Analysis of Structures; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hołowaty, J. New Formula for Creep of Concrete in fib Model Code 2010. Am. J. Mater. Sci. Appl. 2015, 3, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

| Component | LC1 Mix | LC2 Mix |

|---|---|---|

| Dosage [kg/m3] | ||

| Cement CEM I 42.5 N | 409 | 419 |

| Lightweight sintered aggregate Certyd 4/10 | 775 | 802 |

| Sand | 682 | 703 |

| Water | 164 | 209 |

| Admixture BV 18 | 3.7 | 3.8 |

| Admixture SKY 686 | 3.7 | 3.8 |

| Sample No. | εtot ± U | εe ± U | εc ± U | φ ± U |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mm/m] | [mm/m] | [mm/m] | [mm/m] | |

| LC1-1 | 2.55 ± 0.07 | 0.72 ± 0.04 | 1.54 ± 0.07 | 2.14 ± 0.07 |

| LC1-2 | 2.66 ± 0.07 | 0.76 ± 0.04 | 1.61 ± 0.07 | 2.12 ± 0.07 |

| LC1-3 | 2.56 ± 0.07 | 0.74 ± 0.04 | 1.53 ± 0.07 | 2.07 ± 0.07 |

| average value | 2.59 | 0.74 | 1.56 | 2.11 |

| standard deviation | 0.061 | 0.020 | 0.044 | 0.037 |

| Sample No. | εtot ± U | εe ± U | εc ± U | φ ± U |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [mm/m] | [mm/m] | [mm/m] | [mm/m] | |

| LC2-1 | 2.92 ± 0.07 | 0.82 ± 0.04 | 1.65 ± 0.07 | 2.01 ± 0.14 |

| LC2-2 | 3.16 ± 0.08 | 0.87 ± 0.04 | 1.84 ± 0.07 | 2.11 ± 0.14 |

| LC2-3 | 2.64 ± 0.07 | 0.81 ± 0.04 | 1.38 ± 0.07 | 1.70 ± 0.13 |

| average value | 2.91 | 0.83 | 1.62 | 1.94 |

| standard deviation | 0.260 | 0.032 | 0.231 | 0.214 |

| Sample No. | U (εtot) | U (εe) | U (εc) | U (φ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [%] | [%] | [%] | [%] | |

| LC1-1 | 2.75 | 5.56 | 4.55 | 8.42 |

| LC1-2 | 2.63 | 5.26 | 4.35 | 8.02 |

| LC1-3 | 2.73 | 5.41 | 4.58 | 8.22 |

| LC2-1 | 2.40 | 4.88 | 4.24 | 6.96 |

| LC2-2 | 2.53 | 4.60 | 3.80 | 6.62 |

| LC2-3 | 2.65 | 4.94 | 5.07 | 7.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lewiński, P.M.; Fedorczyk, Z.; Więch, P.; Zacharski, Ł. Adequacy of Standard Models for Long-Term Behavior of Lightweight Concrete with Sintered Aggregate Under Cyclic Loading. Materials 2026, 19, 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010059

Lewiński PM, Fedorczyk Z, Więch P, Zacharski Ł. Adequacy of Standard Models for Long-Term Behavior of Lightweight Concrete with Sintered Aggregate Under Cyclic Loading. Materials. 2026; 19(1):59. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010059

Chicago/Turabian StyleLewiński, Paweł M., Zbigniew Fedorczyk, Przemysław Więch, and Łukasz Zacharski. 2026. "Adequacy of Standard Models for Long-Term Behavior of Lightweight Concrete with Sintered Aggregate Under Cyclic Loading" Materials 19, no. 1: 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010059

APA StyleLewiński, P. M., Fedorczyk, Z., Więch, P., & Zacharski, Ł. (2026). Adequacy of Standard Models for Long-Term Behavior of Lightweight Concrete with Sintered Aggregate Under Cyclic Loading. Materials, 19(1), 59. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010059