A Review of Femtosecond Laser Processing for Sapphire

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fabrication of Surface Three-Dimensional Micro/Nano Structures

2.1. Femtosecond Laser Ablation

2.2. Femtosecond Laser Hybrid Processing

2.3. Femtosecond Laser Direct Writing for Micro/Nano Manufacturing

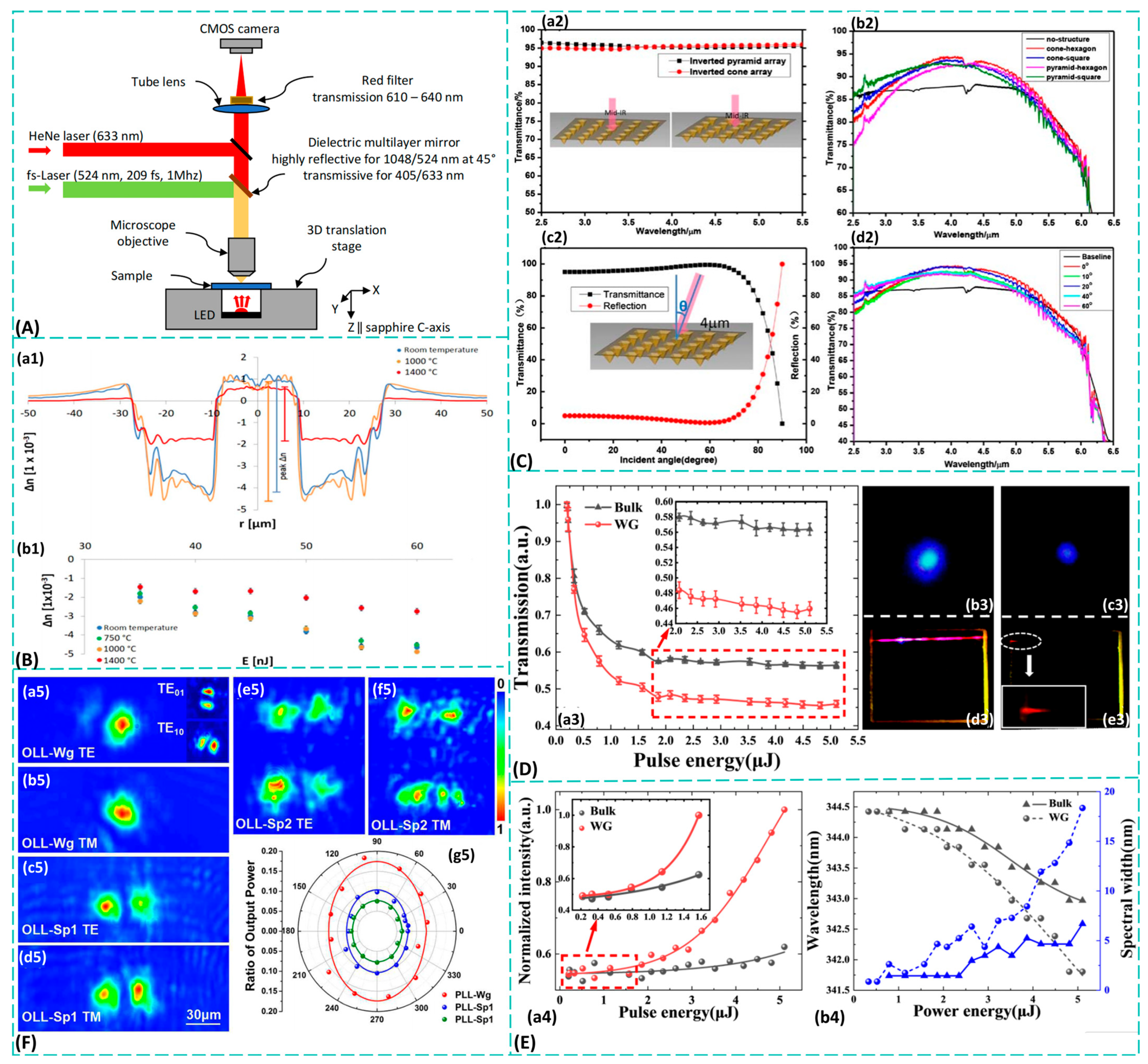

3. Surface and Internal Modification

3.1. Surface Damage Threshold Regulation

3.2. Regulation of Photon Absorption, Reflection, and Transmission Rates

3.3. Surface Hydrophilicity and Hydrophobicity Regulation

3.4. Regulation of Lattice Structure and Mechanical-Chemical Properties

4. Optical Waveguide Writing

4.1. Fabrication of Waveguides

4.2. Fabrication of Waveguide Splitters

5. Grating Fabrication

6. Welding and Joining

7. Summary and Prospects

- (1)

- Currently, femtosecond laser processing of complex three-dimensional structures suffers from low efficiency. Future developments should focus on creating high-repetition-rate femtosecond lasers operating at megahertz frequencies with high average power, while exploring novel material interaction mechanisms to enhance material removal rates without compromising processing quality. Utilizing diffractive optical elements or spatial light modulators to split a single laser beam into multiple parallel processing beams enables simultaneous, synchronized machining of large-area sapphire substrates. This approach represents a key pathway to overcoming industrialization bottlenecks. When combined with more precise galvanometer systems and high-speed motion platforms, optimizing scanning strategies and path planning reduces idle time, thereby achieving efficient, large-area processing coverage.

- (2)

- By leveraging machine learning and artificial intelligence algorithms to perform deep learning on vast amounts of processing parameters and results, a mapping model between laser parameters and processing quality is established. This approach rapidly derives optimal processing solutions, replacing the traditional trial-and-error method and significantly shortening the process development cycle. By integrating real-time monitoring technologies such as plasma spectroscopy and optical coherence tomography, the system dynamically tracks ablation states, defect formation, and structural morphology during processing. It employs feedback control to automatically adjust laser parameters, ensuring consistency and reliability. Additionally, a high-precision multiphysics model of femtosecond laser–sapphire interactions is developed to simulate and predict processing outcomes in virtual space, providing theoretical tools to guide actual processing, predict defects, and suppress them.

- (3)

- On a single sapphire wafer, femtosecond laser-integrated fabrication is used to create waveguides, beam splitters, gratings, and microfluidic channels, enabling the development of “lab-on-a-chip” sensors and miniature spectrometers suitable for extreme environments. By combining surface modification, internal 3D processing, and welding techniques, this approach allows the simultaneous fabrication of macroscopic structures, micron-scale fluid channels, and nanoscale optical features within a single sapphire component. This results in the creation of superior optical windows, corrosion-resistant microreactors, and other advanced devices. Additionally, the potential of waveguides and color centers fabricated in sapphire via femtosecond lasers is being explored for quantum bit storage and transmission, advancing applications in quantum computing and quantum sensing.

- (4)

- Investigate the processing and modification behavior of femtosecond lasers at interfaces between sapphire and other high-performance materials, such as gallium nitride and graphene, to achieve functional connections and structural fabrication of heterostructures, thereby expanding their applications in wide-bandgap semiconductor devices. Conduct in-depth studies on novel physical phenomena arising from interactions between extreme-parameter lasers, such as attosecond pulses and mid-infrared femtosecond lasers and sapphire. Explore emerging effects, including laser-induced crystalline phase transitions and amorphization control, to establish a physical foundation for developing innovative optoelectronic devices.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, Z.; Wang, C.; Jia, X.S.; Ding, Y.L.; Jiang, X.; Wang, S.Y.; Duan, J.A. Ultrahigh Transmittance Biomimetic Fused Quartz Windows Enabled by Frequency-Doubling Femtosecond Laser Processing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 43944–43956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, E.J.; Subhash, G. Static and dynamic indentation response of basal and prism plane sapphire. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2011, 31, 1713–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.S.; Zaidi, Z.H. The suitability of sapphire for laser windows. Meas. Sci. Technol. 1999, 10, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ockenfels, T.; Vewinger, F.; Weitz, A.M. Sapphire optical viewport for high pressure and temperature applications. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2021, 92, 065109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.Q.; Wang, W.L.; Yang, W.J.; Lin, Y.H.; Wang, H.Y.; Lin, Z.T.; Zhou, S.Z. GaN-based light-emitting diodes on various substrates: A critical review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2016, 79, 056501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Guo, L.W.; Jia, H.Q.; Wang, Y.; Xing, Z.G.; Li, W.; Chen, H.; Zhou, J.M. Fabrication of patterned sapphire substrate by wet chemical etching for maskless lateral overgrowth of GaN. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, C182–C185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhigang, F.; Jianjun, L.; Haosu, X.; Wang, Z.; Chunying, G.; Libo, Y. Research Progress on the Growth Technology and Applications of Sapphire Single Crystals. J. Silic. 2011, 39, 880–891. [Google Scholar]

- Barish, B.C.; Billingsley, G.; Camp, J.; Kells, W.P.; Sanders, G.H.; Whitcomb, S.E.; Zhang, L.Y.; Zhu, R.Y.; Deng, P.Z.; Xu, J.; et al. Development of large size sapphire crystals for laser interferometer gravitational-wave observatory. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2002, 49, 1233–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leem, J.W.; Yu, J.S. Wafer-scale highly-transparent and superhydrophilic sapphires for high-performance optics. Opt. Express 2012, 20, 26160–26166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G. Preparation and Sensing Characteristics of High-Temperature Resistant Fiber Bragg Gratings for Harsh Environments. Ph.D. Dissertation, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Buric, M.; Ohodnicki, P.R.; Nakano, J.; Liu, B.; Chorpening, B.T. Review and perspective: Sapphire optical fiber cladding development for harsh environment sensing. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2018, 5, 011102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Shon, U.; Seong, G.H.; Kim, M.H.; Park, B.C.; Hong, S.P. A comparative clinical trial to evaluate efficacy and safety of the 308-nm excimer laser and the gain-switched 311-nm titanium:sapphire laser in the treatment of vitiligo. Photodermatol. Photoimmunol. Photomed. 2020, 36, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.K. Research on Femtosecond Laser Fabrication Technology of Sapphire Micro-Optical Components. Ph.D. Dissertation, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Capuano, L.; Berenschot, J.W.; Tiggelaar, R.M.; Feinaeugle, M.; Tas, N.R.; Gardeniers, J.G.E.; Römer, G. Fabrication of microstructures in the bulk and on the surface of sapphire by anisotropic selective wet etching of laser-affected volumes. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2022, 32, 125003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fangfang, L. Main Growth Methods and Research Status of Sapphire Crystals. Mod. Salt Chem. Ind. 2016, 43, 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.T.; Lu, X.S.; Wu, X.K.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Wang, R.; Yang, D.R.; Pi, X.D. Chemical-Mechanical Polishing of 4H Silicon Carbide Wafers. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 2202369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiufeng, J. Sapphire Crystal Growth Technology and Equipment. Spec. Equip. Electron. Ind. 2011, 40, 7–10+22. [Google Scholar]

- Liuchen, L.; Jinsheng, F. Current Status and Development Trends of Sapphire Crystal Growth Technology in China. J. Artif. Cryst. 2012, 41, 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Khattak, C.P.; Schmid, F. Growth of the world’s largest sapphire crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 2001, 225, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budenkova, O.N.; Vasiliev, M.G.; Yuferev, V.S.; Bystrova, E.N.; Kalaev, V.V.; Bermúdez, V.; Diéguez, E.; Makarov, Y.N. Simulation of global heat transfer in the Czochralski process for BGO sillenite crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 2004, 266, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.C.; Zuo, H.B.; Meng, S.H. Preparation of Large-Size Sapphire Single Crystals by the Kyropoulos Method. J. Artif. Crystallogr. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Budenkova, O.; Vasiliev, M.; Yuferev, V.; Kalaev, V. Effect of internal radiation on the solid-liquid interface shape in low and high thermal gradient Czochralski oxide growth. J. Cryst. Growth 2007, 303, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, D.; Sumathi, R.R.; Wilke, H. The interface inversion process during the Czochralski growth of high melting point oxides. J. Cryst. Growth 2004, 265, 494–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, J.; Mo, H.; Ling, K.; Chu, J.; Chen, X.; Xu, J. Enhancing the Machinability of Sapphire via Ion Implantation and Laser-Assisted Diamond Machining. Micromachines 2025, 16, 1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H. Research on Sapphire Processing Technology. Mech. Des. Manuf. Eng. 2000, 52–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.X.; Cui, M.B.; Xiao, Y. Research on Improving Sand Erosion Resistance of Infrared Rectifying Housings. Aircr. Maint. Eng. 2025, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Zhao, H.; Gang, L.Z.; Yao, Y.D.; Ma, P. The full aperture processing technical research in fabricating large sapphire window element. In Proceedings of the Second Target Recognition and Artificial Intelligence Summit Forum, Shenyang, China, 28–30 August 2019; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020; p. 11427. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.Z.; Zhou, S.M.; Xu, J. Research on Chemical Mechanical Polishing Technology for Sapphire Substrates. J. Artif. Crystallogr. 2004, 441–447. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, M.H.; Niu, X.H.; Hou, Z.Y. Research Progress on Sapphire Chemical Mechanical Polishing Slurry. Electroplat. Coat. 2022, 41, 211–216. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.W. Study on the Optimization of Chemical Mechanical Polishing Slurry Components for Sapphire Wafers and Its Polishing Process. Master’s Thesis, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, S.B.; Wang, W.W.; Liu, P.; Zhang, Y.H.; Zhao, X.M.; Li, J.B.; Xiao, M.S.; Wang, Y.Z.; Li, J.; Shao, X.P. Recent Advances in Applications of Ultrafast Lasers. Photonics 2024, 11, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.C.; Lei, L.X.; Lin, S.J.; Tian, S.; Tian, W.L.; Yu, Z.Y.; Li, F. Metal Material Processing Using Femtosecond Lasers: Theories, Principles, and Applications. Materials 2024, 17, 3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumann, M.; Bückmann, T.; Gruhler, N.; Wegener, M.; Pernice, W. Hybrid 2D-3D optical devices for integrated optics by direct laser writing. Light-Sci. Appl. 2014, 3, e175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugioka, K. Progress in ultrafast laser processing and future prospects. Nanophotonics 2017, 6, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.C.; Bai, S.; Wang, S.T.; Hu, A.M. Ultra-Short Pulsed Laser Manufacturing and Surface Processing of Microdevices. Engineering 2018, 4, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orazi, L.; Romoli, L.; Schmidt, M.; Li, L. Ultrafast laser manufacturing: From physics to industrial applications. Cirp Ann.-Manuf. Technol. 2021, 70, 543–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubir, A.; Shah, L.; Richardson, K.; Richardson, M. Practical uses of femtosecond laser micro-materials processing. Appl. Phys. A-Mater. Sci. Process. 2003, 77, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorobyev, A.Y.; Guo, C.L. Direct femtosecond laser surface nano/microstructuring and its applications. Laser Photonics Rev. 2013, 7, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korte, F.; Serbin, J.; Koch, J.; Egbert, A.; Fallnich, C.; Ostendorf, A.; Chichkov, B.N. Towards nanostructuring with femtosecond laser pulses. Appl. Phys. A-Mater. Sci. Process. 2003, 77, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer-Beg, S.; Perrie, W.; Rathbone, S.; Wright, J.; Weaver, W.; Champoux, H. Femtosecond laser microstructuring of materials. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1998, 127, 875–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugioka, K.; Cheng, Y. Femtosecond laser three-dimensional micro- and nanofabrication. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2014, 1, 041303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.F.; Li, J.X.; Liu, M.L.; Yang, D.Y.; Li, F.J. A Review of Effects of Femtosecond Laser Parameters on Metal Surface Properties. Coatings 2022, 12, 1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubiano, C.A.R.; Della Picca, R.; Mitnik, D.M.; Silkin, V.M.; Gravielle, M.S. Induced-field enhancement of band-structure effects in photoelectron spectra from Al surfaces by ultrashort laser pulses. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 95, 033401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraggi, M.N.; Gravielle, M.S.; Silkin, V.M. Photoelectron emission from metal surfaces by ultrashort laser pulses. Phys. Rev. A 2006, 73, 032901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Li, X.; Qi, L. Investigation on single-pulse 266 nm nanosecond laser and 780 nm femtosecond laser ablation of sapphire. In Proceedings of the Conference on Advanced Laser Processing and Manufacturing IV, Online, 11–16 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.X.; Jia, T.Q.; Feng, D.H.; Xu, Z.Z. Ablation induced by femtosecond laser in sapphire. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2004, 225, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudrius, T.; Slekys, G.; Juodkazis, S. Surface-texturing of sapphire by femtosecond laser pulses for photonic applications. J. Phys. D-Appl. Phys. 2010, 43, 145501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, M.E.; Gagnon, J.E.; Fryer, B.J. Experimental study on 785 nm femtosecond laser ablation of sapphire in air. Laser Phys. Lett. 2015, 12, 066103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.W.; Chen, C.Y.; Chang, T.L.; Ting, C.J.; Wang, C.P.; Chou, C.P. Sapphire surface patterning using femtosecond laser micromachining. Appl. Phys. A-Mater. Sci. Process. 2012, 109, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Rueda, J.; Siegel, J.; Galvan-Sosa, M.; de la Cruz, A.R.; Garcia-Lechuga, M.; Solis, J. Controlling ablation mechanisms in sapphire by tuning the temporal shape of femtosecond laser pulses. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B-Opt. Phys. 2015, 32, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.J.; Lin, L.C.; Wu, W.Q.; Li, Z.G. Fabrication of through sapphire vias by femtosecond laser bidirectional drilling. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2025, 40, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Cao, Q.; Deng, H.Y.; Li, J.L.; Zhu, X.Z.; Li, B.Y.; Liu, F.; Peng, S.; Zou, J.J.; Chen, M. High roundness and cross-scale capillary fabrication on sapphire by femtosecond laser ablation. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 177, 111206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.G.; Li, Y.; Lin, W.X.; Hong, M.H. High-aspect-ratio crack-free microstructures fabrication on sapphire by femtosecond laser ablation. Opt. Laser Technol. 2020, 132, 106472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Huo, J.; Chen, Q.; Guo, L.; Zhao, K.; Luo, M.; Zhu, Q.; Li, J.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, Q. Microcrackless weld formation under unilateral melting in laser transmission welding of sapphire and stainless steel. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 141, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.Q.; Chen, Q.D.; Sun, H.B. Scribing of sapphire by dry-etching-asisted femtosecond laser fabrication. Chin. Sci. Bull.-Chin. 2021, 66, 711–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.T.; Jiang, Y.; Deng, H.; Gao, H.C.; Tang, C.J.; Wang, X.F. All-sapphire-based optical fiber pressure sensor with an ultra-wide pressure range based on femtosecond laser micromachining and direct bonding. Opt. Express 2023, 31, 41967–41978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, J.; Zhang, Y.T.; Hui, D. Optical Fiber Pressure Sensor Based on Sapphire Wafers Processed by Femtosecond Laser. Acta Opt. Sin. 2023, 43, 1506001. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.C.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, Z.J.; Li, S.X.; Zheng, J.X.; Xia, H.; Wang, L. Wafer-scale high aspect-ratio sapphire periodic nanostructures fabricated by self-modulated femtosecond laser hybrid technology. Opt. Express 2022, 30, 32244–32255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.W.; Lu, Y.M.; Fan, H.; Xia, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.L. Wet-etching-assisted femtosecond laser holographic processing of a sapphire concave microlens array. Appl. Opt. 2018, 57, 9604–9608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.Q.; Zhang, Y.L.; Li, Q.K.; Zheng, J.X.; Lu, Y.M.; Juodkazis, S.; Chen, Q.D.; Sun, H.B. Biomimetic sapphire windows enabled by inside-out femtosecond laser deep-scribing. Photonix 2022, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xu, X.J.; Zhou, H.B.; Wang, C.; Jia, X.S.; Ding, Y.L.; Gao, Z.; Wang, S.Y.; Liu, L.P.; Duan, J. Femtosecond laser burst mode combined with wet etching for fabricating surface microholes on sapphire. Appl. Phys. A 2025, 131, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.B.; Joshya, R.S.; Yang, J.J.; Guo, C.L. Controllable fabrication of polygonal micro and nanostructures on sapphire surfaces by chemical etching after femtosecond laser irradiation. Opt. Mater. Express 2019, 9, 2994–3005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katahira, K.; Ogawa, Y.; Morita, S.; Yamazaki, K. Experimental investigation for optimizing the fabrication of a sapphire capillary using femtosecond laser machining and diamond tool micromilling. Cirp Ann.-Manuf. Technol. 2020, 69, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kefer, S.; Zettl, J.; Esen, C.; Hellmann, R. Femtosecond Laser-Based Micromachining of Rotational-Symmetric Sapphire Workpieces. Materials 2022, 15, 6233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallarés-Aldeiturriaga, D.; Claudel, P.; Granier, J.; Travers, J.; Guillermin, L.; Flaissier, M.O.; D’Augeres, P.B.; Sedao, X. Femtosecond Laser Engraving of Deep Patterns in Steel and Sapphire. Micromachines 2021, 12, 804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, C.K.; Chen, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Ju, B.F.; Chen, Y.L. Femtosecond laser micro-machining of three-dimensional surface profiles on flat single crystal sapphire. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 170, 110205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.Y.; Dou, J.; Dong, X.Y.; Duan, W.Q. Research on sapphire micro-blind-hole machining based on femtosecond laser. Ferroelectrics 2020, 563, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Wang, Z.H.; Hua, J.G.; Li, Q.K.; Li, A.W.; Yu, Y.H. Sub-diffraction-limit fabrication of sapphire by femtosecond laser direct writing. Acta Phys. Sin. 2017, 66, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.T.; Hu, J.P. Femtosecond laser micromachining of high quality groove on sapphire surface. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Advanced Design and Manufacturing Engineering (ADME 2012), Taiyuan, China, 16–18 August 2012; pp. 2213–2216. [Google Scholar]

- Elgohary, A.; Block, E.; Squier, J.; Koneshloo, M.; Shaha, R.K.; Frick, C.; Oakey, J.; Aryana, S.A. Fabrication of sealed sapphire microfluidic devices using femtosecond laser micromachining. Appl. Opt. 2020, 59, 9285–9291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Lan, X.W.; Huang, J.; Wang, H.Z.; Jiang, L.; Xiao, H. Comparison of Silica and Sapphire Fiber SERS Probes Fabricated by a Femtosecond Laser. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2014, 26, 1299–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Zhang, D.Q.; Chen, T.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, T.L.; Huang, F.Q.; Zhong, Y.; Si, J.H.; Hou, X. Polarization influence on femtosecond laser-induced surface damage and electron plasma ultrafast dynamics in sapphire. J. Appl. Phys. 2025, 137, 183102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Chen, T.; Zhu, W.Y.; Shen, T.L.; Si, J.H. Temporal-spatial dynamics of electronic plasma in a femtosecond laser-induced sapphire microstructure. Appl. Opt. 2023, 62, 3416–3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.L.; Wang, H.L.; Cheng, G.H.; Jiang, F.; Lu, J.; Xu, X.P. Improvement of ablation capacity of sapphire by gold film-assisted femtosecond laser processing. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2020, 128, 106007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.L.; Zhang, P.C.; Cheng, G.H.; Jiang, F.; Lu, X.Z. Crystalline orientation effects on material removal of sapphire by femtosecond laser irradiation. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 23501–23508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Wang, C.; Duan, J.; Guo, C.L. Femtosecond laser-induced periodic surface structural formation on sapphire with nanolayered gold coating. Appl. Phys. A-Mater. Sci. Process. 2016, 122, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, R.; Sharma, S.P.; Almeida, A.; Cangueiro, L.T.; Oliveira, V. Surface morphology and phase transformations of femtosecond laser-processed sapphire. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 288, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Mei, W.; Wang, Y. Simulation of femtosecond laser ablation sapphire based on free electron density. Opt. Laser Technol. 2019, 113, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.T.; Ji, C.Y.; Li, C.K.; Tian, Z.Q.; Wang, X.; Lei, C.; Liu, S. Multiphoton Absorption Simulation of Sapphire Substrate under the Action of Femtosecond Laser for Larger Density of Pattern-Related Process Windows. Micromachines 2021, 12, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, Z.; He, L.B.; Cui, Q.N.; Gao, W.H.; Yin, Y.C.; Meng, L.Y.; Chen, C.; Liao, Y.; Leng, Y.X.; Wang, Z.W.; et al. Fabrication of sapphire optical windows with infrared transmittance enhancement and visible transmittance reduction by femtosecond laser direct writing. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 188, 112989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Y.B.; Li, Q.Z.; Tang, F.; Ye, X.; Zheng, W.G. A Method for Preparing Surface Sub-Microstructures on Sapphire Surfaces Using Femtosecond Laser Processing Technology. Coatings 2024, 14, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Zhu, W.W.; Zou, H.H.; Zu, G.Q.; Han, Y.; Ran, X. High strength and high light transmittance sapphire/sapphire joints bonded using a La2O3-Al2O3-SiO2 glass filler. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2022, 42, 4607–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Duan, J.; Sun, X.Y.; Wang, C.; Luo, Z. Formation of superwetting surface with line-patterned nanostructure on sapphire induced by femtosecond laser. Appl. Phys. A-Mater. Sci. Process. 2015, 119, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, D.D.; Yu, Z.; Zou, T.T.; Lin, Y.C.; Kong, W.C.; Yang, J.J. Long-Time Persisting Superhydrophilicity on Sapphire Surface via Femtosecond Laser Processing with the Varnish of TiO2. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.K.; Yin, K.; Dong, X.R.; Luo, Z.; Duan, J.A. Femtosecond laser fabrication of robust underwater superoleophobic and anti-oil surface on sapphire. AIP Adv. 2017, 7, 115224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.W.; Wei, H.Y.; Li, J.X.; Lu, J.G.; Lin, Q.D.; Zhang, Y. Wettability Control of Sapphire by Surface Texturing in Combination with Femtosecond Laser Irradiation and Chemical Etching. Chemistryselect 2020, 5, 9555–9562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Nie, Z.G.; Ma, L.; Zhang, F.T.; Hao, M.M.; Wang, B.; Zhao, W.R.; Luo, L.; Zhang, J.H.; Huang, C.C. Coherent phonon dynamics in a c-plane sapphire crystal before and after intense femtosecond laser irradiation. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 16003–16011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.C.; Zou, J.; Lin, X.Y.; Wu, W.J.; Li, W.B.; Yang, B.B.; Shi, M.M. Quality-Improved GaN Epitaxial Layers Grown on Striped Patterned Sapphire Substrates Ablated by Femtosecond Laser. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.L.; He, J.H.; Wang, C.; Ding, K.W.; Ding, Y.L.; Yan, D.J.; Lin, N.; Duan, J.A. Micro-nanostructures fabricated by femtosecond laser for interface joint strengthening of Cu/sapphire. Opt. Laser Technol. 2025, 186, 112737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagawa, R.; Goto, K.; Eryu, O. Femtosecond-Laser Irradiation onto Sapphire Substrates in an N2 Ambient Atmosphere. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Nitride Semiconductors (ICNS), Strasbourg, France, 24–28 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.Y.; Hu, Y.W.; Sun, X.Y.; Wang, C.; Zhou, J.Y.; Dong, X.R.; Yin, K.; Chu, D.K.; Duan, J. Chemical etching mechanism and properties of microstructures in sapphire modified by femtosecond laser. Appl. Phys. A 2017, 123, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.Y.; Zhou, G.Q.; Xu, J.; Deng, P.Z.; Gan, F.X. Femtosecond laser irradiation on YAG and sapphire crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 2004, 260, 181–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, S.; Withford, M.J.; Fuerbach, A. Direct femtosecond laser written waveguides in bulk Ti3+:Sapphire. In Proceedings of the Conference on Frontiers in Ultrafast Optics—Biomedical, Scientific, and Industrial Applications X, San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–26 January 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler, S.; Krenn, J.R.; Wahl, J.; Zesar, A.; Colombe, Y.; Schüppert, K.; Rössler, C.; Sommer, C.; Hurdax, P.; Lichtenegger, P.; et al. Femtosecond laser-written waveguides in sapphire for visible light delivery. Opt. Contin. 2025, 4, 1212–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérubé, J.P.; Lapointe, J.; Dupont, A.; Bernier, M.; Vallée, R. Femtosecond laser inscription of depressed cladding single-mode mid-infrared waveguides in sapphire. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.K.; Cao, J.J.; Yu, Y.H.; Wang, L.; Sun, Y.L.; Chen, Q.D.; Sun, H.B. Fabrication of an anti-reflective microstructure on sapphire by femtosecond laser direct writing. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pätzold, W.M.; Ayhan, D.; Uwe, M. Low-loss curved waveguides in polymers written with a femtosecond laser. Opt. Express 2017, 25, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Su, J.Q.; Zeng, X.M.; Deng, G.L.; Zhou, S.H. Enhanced nonlinear effects in femtosecond laser-inscribed depressed cladding waveguides in sapphire crystals. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 3933–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhou, H.; Deng, G.L.; Zhou, S.H. Comparison of supercontinuum generation in bulk sapphire and femtosecond-laser-inscribed waveguides. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 158, 108908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokkar, T.Z.N.; El-Farahaty, K.A.; Ramadan, W.A.; Wahba, H.H.; Raslan, M.I.; Hamza, A.A. Nonray-tracing determination of the 3D refractive index profile of polymeric fibres using single-frame computed tomography and digital holographic interferometric technique. J. Microsc. 2015, 257, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.Y.; Jiao, Y.; de Aldana, J.R.V.; Chen, F. Ti:Sapphire micro-structures by femtosecond laser inscription: Guiding and luminescence properties. Opt. Mater. 2016, 58, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apostolopoulos, V.; Laversenne, L.; Colomb, T.; Depeursinge, C.; Salathé, R.P.; Pollnau, M.; Osellame, R.; Cerullo, G.; Laporta, P. Femtosecond-irradiation-induced refractive-index changes and channel waveguiding in bulk Ti3+:Sapphire. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 85, 1122–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.Y.; Zhang, L.M.; Xing, H.G.; Romero, C.; de Aldana, J.R.V.; Chen, F. Cladding waveguide splitters fabricated by femtosecond laser inscription in Ti:Sapphire crystal. Opt. Laser Technol. 2018, 103, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.Y.; Zhang, L.M.; Lv, J.M.; Zhao, Y.F.; Romero, C.; de Aldana, J.R.V.; Chen, F. Optical-lattice-like waveguide structures in Ti: Sapphire by femtosecond laser inscription for beam splitting. Opt. Mater. Express 2017, 7, 1942–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollesen, L.; Nehari, A.; Labor, S.; Goget, G.A.; Guignier, D.; Lebbou, K. Impact of graphite and alumina ceramic thermal insulation on the growth of undoped sapphire plates by micro-pulling down. Mater. Res. Bull. 2026, 195, 113846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Jing, X.; Wang, H.; Peng, J.; Yin, P.; Wang, R.; Wu, A. A broadband polarization beam splitter on a 3-μm-thick SOI platform based on asymmetric Mach-Zehnder interferometer. Opt. Commun. 2025, 596, 132585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.X.; Gao, B.R.; Xue, Y.F.; Luo, Z.Y.; Han, S.G.; Liu, X.Q.; Chen, Q.D. Fabrication of Sapphire Grating by Femtosecond Laser Assisted Etching. Acta Photonica Sin. 2021, 50, 84. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.; Jang, W.; Kim, T.; Moon, A.; Lim, K.S.; Lee, M.; Sohn, I.B.; Jeong, S. Nanostructure and microripple formation on the surface of sapphire with femtosecond laser pulses. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 093518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstuch, A.; Ishaaya, A.A. Femtosecond laser induced of Nano-gratings on a thin GaN layer grown on a sapphire substrate. In Proceedings of the Conference on Lasers and Electro-Optics Europe/European Quantum Electronics Conference (CLEO/Europe-EQEC), Munich, Germany, 23–27 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.K.; Yu, Y.H.; Wang, L.; Cao, X.W.; Liu, X.Q.; Sun, Y.L.; Chen, Q.D.; Duan, J.A.; Sun, H.B. Sapphire-Based Fresnel Zone Plate Fabricated by Femtosecond Laser Direct Writing and Wet Etching. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2016, 28, 1290–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelmakas, E.; Kadys, A.; Malinauskas, T.; Paipulas, D.; Dobrovolskas, D.; Dmukauskas, M.; Selskis, A.; Juodkazis, S.; Tomasiunas, R. A systematic study of light extraction efficiency enhancement depended on sapphire flipside surface patterning by femtosecond laser. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2015, 48, 285104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grobnic, D.; Mihailov, S.J.; Smelser, C.W.; Ding, H.M. Sapphire fiber Bragg grating sensor made using femtosecond laser radiation for ultrahigh temperature applications. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 2004, 16, 2505–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstuch, A.; Westreich, O.; Sicron, N.; Ishaaya, A.A. Femtosecond laser inscription of Bragg gratings on a thin GaN film grown on a sapphire substrate. Opt. Lasers Eng. 2018, 109, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, X.Y.; Yu, Y.S.; Wei, W.H.; Guo, Q.; Qin, L.; Ning, Y.Q.; Wang, L.J.; Sun, H.B. Femtosecond Laser-Inscribed High-Order Bragg Gratings in Large-Diameter Sapphire Fibers for High-Temperature and Strain Sensing. J. Light. Technol. 2018, 36, 3302–3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Z.; He, J.; He, J.; Xu, B.J.; Chen, R.X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Y.T.; Wang, Y.P. Efficient point-by-point Bragg grating inscription in sapphire fiber using femtosecond laser filaments. Opt. Lett. 2021, 46, 2742–2745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Z.; He, J.; Liao, C.R.; Yang, K.M.; Gu, K.K.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.F.; Ouyang, Z.B.; Wang, Y.P. Sapphire fiber Bragg gratings inscribed with a femtosecond laser line-by-line scanning technique. Opt. Lett. 2018, 43, 4562–4565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alla, D.R.; Neelakandan, D.P.; Mumtaz, F.; Gerald, R.E.; Bartlett, L.; O’Malley, R.J.; Smith, J.D.; Huang, J. Cascaded Sapphire Fiber Bragg Gratings Inscribed by Femtosecond Laser for Molten Steel Studies. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Yu, Y.S.; Zheng, Z.M.; Chen, C.; Wang, P.L.; Tian, Z.N.; Zhao, Y.; Ming, X.Y.; Chen, Q.D.; Yang, H.; et al. Femtosecond Laser Inscribed Sapphire Fiber Bragg Grating for High Temperature and Strain Sensing. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 2019, 18, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wu, J.F.; Xu, X.Z.; Liao, C.R.; Liu, S.; Weng, X.Y.; Liu, L.W.; Qu, J.L.; Wang, Y.P. Femtosecond Laser Plane-by-Plane Inscription of Bragg Gratings in Sapphire Fiber. J. Light. Technol. 2023, 41, 7014–7020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.J.; Yan, C.Y.; Liu, X.F.; Sun, S.Z.; Qiu, J.R. Efficient fabrication of volume diffraction gratings in sapphire with a femtosecond laser. Mater. Lett. 2025, 392, 138476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, F.; Zhang, B.H.; Dey, K.; Smith, J.D.; O’Malley, R.J.; Huang, J. Discrimination of Temperature and Strain by Characterizing Two Femtosecond Laser-Written Coincident Sapphire Fiber Bragg Gratings for Harsh Environment Applications. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumtaz, F.; Tekle, H.; Zhang, B.H.; Smith, J.D.; O’Malley, R.J.; Huang, J. Highly cascaded first-order sapphire optical fiber Bragg gratings fabricated by a femtosecond laser. Opt. Lett. 2023, 48, 4380–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Xu, X.Z.; He, J.; Wu, J.F.; Bai, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.P. Single-mode helical sapphire fiber Bragg grating sensors fabricated by femtosecond laser direct writing technology. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Optical Fiber Sensors, Porto, Portugal, 25–30 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Liu, S.R.; Pan, X.P.; Wang, B.; Tian, Z.N.; Chen, C.; Chen, Q.D.; Yu, Y.S.; Sun, H.B. Femtosecond laser inscribed helical sapphire fiber Bragg gratings. Opt. Lett. 2021, 46, 4836–4839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Li, X.Y.; Lu, F.G.; Xu, J.Y.; Xu, R.; Zhang, X.F.; Zhao, Y.W.; Sun, X.; Pan, R.; Lin, P.P.; et al. Femtosecond laser-induced honeycomb structure on the interface for the micro-welding of YSZ/sapphire. J. Adv. Ceram. 2025, 14, 9221052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhang, S.Y.; Xu, J.Y.; Guo, B.X.; Li, S.W.; Ye, F.Q.; Li, H.; Chen, S.J.; Lin, T.S.; He, P.; et al. The influence of femtosecond laser surface texturing on the microstructure and mechanical properties of sapphire-ZrO2 brazed joints. J. Manuf. Process. 2025, 154, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soheil, M.; Davood, A.; Iraj, A. Ultrasonic Welding of Glass Fiber-Reinforced Epoxy Composite Using Thermoplastic Nanocomposites Interlayer. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2024, 77, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Yang, D.; Zhou, T.S.; Feng, Y.H.; Dong, Z.S.; Yan, Z.Y.; Li, P.; Yang, J.; Chen, S.J. Micro-welding of sapphire and metal by femtosecond laser. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 21384–21392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Fu, Y.Z.; Jia, X.S.; Li, K.; Wang, C. Femtosecond Laser Single-Spot Welding of Sapphire/Invar Alloy. Materials 2025, 18, 3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yi, Z.X.; Jia, X.S.; Li, K.; Wang, C.; Duan, J.A. Micro-welding of non-optical contact sapphire/metal using Burst femtosecond laser. Mater. Lett. 2024, 377, 137540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhao, J.X.; Zhang, L.J.; Na, S.J. Femtosecond laser welding of sapphire-copper using a thin film titanium interlayer. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 177, 111063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liang, C.; Feng, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y. A Review of Femtosecond Laser Processing for Sapphire. Materials 2026, 19, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010206

Liang C, Feng J, Liu H, Sun Y, Zhang Y, Tian Y. A Review of Femtosecond Laser Processing for Sapphire. Materials. 2026; 19(1):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010206

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Chengxian, Jiecai Feng, Hongfei Liu, Yanning Sun, Yilian Zhang, and Yingzhong Tian. 2026. "A Review of Femtosecond Laser Processing for Sapphire" Materials 19, no. 1: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010206

APA StyleLiang, C., Feng, J., Liu, H., Sun, Y., Zhang, Y., & Tian, Y. (2026). A Review of Femtosecond Laser Processing for Sapphire. Materials, 19(1), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010206